Abstract

To understand the prenatal origin of developmental and psychiatric disorders, studies in laboratory animals are imperative. However, the developmental pace differs between humans and animals; hence, corresponding human ages must be estimated to infer the most vulnerable developmental timings in humans. Because rats and mice are extensively used as models in developmental research, a correspondence between human foetal ages and rodents’ ages must be precisely determined; thus, developing a translational model is of utmost importance. Optimizing a translational model involves classifying the brain regions according to developmental paces, but previous studies have conducted this classification arbitrarily. Here we used a clustering method and showed that the brain regions can be classified into two groups. To quantify the developmental pace, we gathered data for a range of development events in humans and rodents and created a linear mixed model that translates human developmental timings into the corresponding rat timings. We conducted an automatic classification of brain regions using an EM algorithm and obtained a model to translate human foetal age to rat age. Our model could predict rat developmental timings within 2.5 days of root mean squared error. This result provides useful information for designing animal studies and clinical tests.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Human development is affected by several environmental factors, such as stress, nutrition and sensory inputs1,2,3. To understand the prenatal origin of human developmental disorders, studies in laboratory animals are imperative. However, the developmental pace differs between humans and other animals4,5,6,7; hence, corresponding human ages must be estimated to infer the most vulnerable developmental timings in humans. Because several developmental events have sensitive periods8,9,10, the precise timings are necessary to design clinical tests.

Developmental stages differ regionally between the central nervous system and body parts, as well as according to the developmental origin5,6,7. For example, in several species, animals are born before the eyelids open4, whereas human infants can open their eyes before birth11. Thus, the sequential order of development is different among mammal species, indicating that translation between animal age and human age must be calculated in relation to different body parts. Because the time-keeping mechanisms underlying the development of different body parts remain unknown, the body parts have to be classified by systematically clustering the empirical data. However, previous studies have used not only brain regions but also functional categories for classification, such as the limbic system, which included broad brain regions5,6.

In the present study, we classified whole brain regions into multiple groups according to their developmental pace. We surveyed the published literature on developmental events in the prenatal human and prenatal and postnatal rodent brains and made an exhaustive list of comparative developmental events. Because rodents are extensively used in developmental research, their developmental information is extensive and the translation between rodents and humans is valuable. We created a linear mixed model12 and selected the most plausible model using an extension of Akaike’s information criterion13 (EIC)14.

Results

Collection of developmental timing

We collected data on 94 developmental events with comparable timing in humans and rodents from 153 published studies (Table 1, Table S1 in Supplementary Information). The publication list was described in Table S1. Several developmental events were excluded because the cellular type and/or developmental origin, as determined by chemical cues, were not available. When discrepancies were found in published rat data, we searched for the latest experimental results in mice and surveyed the mechanism and order of the developmental events. We then selected the most consistent results according to the temporal sequence.

In contrast to a previous study6, six developmental events (16, 21, 52, 65, 81 and 82) overlapped. The number of developmental events identified in our human experimental dataset was larger than that in the translating time project6 (94 and 75 including 20 postnatal events, respectively). The number of developmental events without human data in our study was smaller than in theirs (0 and 196, respectively). Methodological differences may account for a small amount of overlap. We mainly used the onset times of chemical markers in the prenatal human brain to identify cell types. In contrast, the previous study analysed developmental changes detected by classical histological techniques in prenatal and postnatal human6. The strength of our dataset was the fact that developmental events without human data were not included.

Our collection of human developmental events included one in vivo electrophysiological analysis of a premature human infant (event 74) and one in vitro slice experiment (event 70). However, almost all developmental events were based on anatomical data. The developmental events were subdivided into the following: four ‘retina’, four ‘midbrain’, five ‘thalamus’, five ‘subcortex’, six ‘medulla/pons’, six ‘cerebellum’, seven ‘dorsal root/trigeminal ganglion (DRG)’, eight ‘spinal cord’, eight ‘allocortex’, eleven ‘hypothalamus’, fifteen ‘isocortex’ and thirteen others (see Methods, Table 1 and Table S1 in Supplementary Information).

Estimation of the linear mixed model

First, we decided not to use birth-related developmental events (47 and 94) for analysis because we could not rule out the possibility that these events were outliers. A translational model of the hypothalamus using event 47 is described in Supplementary Information (Figure S1).

We estimated the linear mixed model with a categorical value [i.e. group of brain regions], using the EM algorithm15 to maximize the log-likelihood. We used events 1 to 79 to classify brain regions. We increased the predefined group number until EIC became the minimum. However, when the group number was greater than five, the EM algorithm did not converge because standard deviation could not be calculated due to lack of samples in the smallest group. As a result, the optimized group number was four. EIC of one-group, two-group, three-group and four-group models were 428.4, 369.0, 361.9 and 360.3, respectively. The estimation error of the translation of human foetal age to rat age was 2.4 days of root mean squared error.

The automatically determined classification of brain regions revealed that developmental events in the spinal cord, midbrain and thalamus belong to the same group. The second group consisted of the medulla/pons and retina. The third group consisted of the subcortex, isocortex and cerebellum. The fourth group consisted of developmental events in the DRG, allocortex and hypothalamus. These results are summarized in Table 1 and Fig. 1.

Optimized linear mixed model. Our analysis revealed that brain regions could be classified into four groups by comparing the time of development between humans and rats. The filled circles represent developmental timing. The lines represent the optimized regression line. Green, cyan, magenta and orange represent clusters of the spinal cord, medulla, cerebral cortex and hypothalamus, respectively.

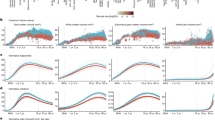

Comparison of the developmental pace

We performed a bootstrapping hypothesis test16,17 with the Benhamini–Hochberg method18 to compare the slopes of the regression models. In descending order of developmental pace: groups A4, B4, C4 and D4 (1.43 ± 0.1, 1.12 ± 0.24, 0.82 ± 0.05 and 0.69 ± 0.06; Fig. 2A). The developmental pace of group A4 was comparable to that of group B4 (n = 27, P > 0.1). The developmental pace of group C4 was comparable to that of group D4 (n = 51, P > 0.1). In contrast, the developmental pace of group D4 was significantly slower than those of groups A4 (n = 42, P < 0.01) and B4 (n = 35, P < 0.01). The developmental pace of group C4 was significantly slower than that of group A4 (n = 43, P < 0.02) and showed a trend toward being slower than group B4 (n = 35, P < 0.06).

Next, we compared the estimated onset of neurogenesis from the timing of neural tube closure in humans (4 pcw)19 using the bootstrapping hypothesis method16,17 with Benhamini–Hochberg method18. However, we could not observe significant differences in onset between groups (A4: 11.0 ± 0.8, B4: 11.8 ± 2.5, C4: 10.7 ± 0.6 and D4: 10.5 ± 0.9. A4 vs B4: n = 27, P > 0.8, A4 vs. C4: n = 43, P > 0.7, A4 vs. D4: n = 42, P > 0.7, B4 vs. C4: n = 36, P > 0.8, B4 vs. D4: n = 35, P > 0.8 and C4 vs. D4: n = 51, P > 0.8) (Fig. 2B).

We combined groups A4 and B4 to form group A2 and groups C4 and D4 to form group B2 because neither developmental pace nor onset were significantly different between groups A4 and B4 and between the groups C4 and D4. We confirmed that the developmental pace was significantly different between groups A2 and B2 (A2: 1.3 ± 0.08, B2: 0.78 ± 0.05 and A2 vs. B2: n = 78, P < 0.005) (Fig. 2C). Developmental onset was not significantly different between groups A2 and B2 (A2: 11.2 ± 0.7, B2: 10.3 ± 0.6 and A2 vs. B2; n = 78, P > 0.3) (Fig. 2D). Finally, to rule out the possibility that the combination of developmental events in different brain regions caused differences in developmental paces, we confirmed that the developmental paces were significantly different between brain regions when the regression line was through the predefined onset point (E11 in rat and 4 weeks in human) (Supplementary Figure S2 and Supplementary Table S3).

Consequently, we obtained the following linear mixed model using all developmental events, excluding events 47 and 94 (Fig. 3):

Optimised linear mixed model. We combined pairs (group A4 and B4 and group C4 and D4) because the slope and onset were not significantly different. The filled circles represent developmental timing. The lines indicate the optimised regression line. Green represents a cluster comprising the brainstem and spinal cord. The magenta represents a cluster comprising the DRG, cerebral cortex, cerebellum and hypothalamus.

Group 2 A (the spinal cord and brainstem): rat_pcd = 1.258 × human_pcw + 6.832.

Group 2B (the cerebellum, hypothalamus and cortex): rat_pcd = 0.774 × human_pcw + 7.417.

Finally, we examined the posterior probability that each developmental event is a member of groups 2 A and B2 (Supplementary Table S2). The group with the maximum posterior probability was not always equal to the group of the event’s corresponding brain region. Because the maximum posterior probability was highly correlated with the timing of developmental events (Spearman’s rank correlation, n = 94, rho = 0.8, P = 5e-25; Fig. 4), these mismatches can be explained by the fact that the classification of each event close to the onset of neurogenesis was difficult. Thus, our classification highly relied on the developmental events during the late human prenatal period.

Discussion

In the present study, we used a model selection approach to classify brain regions into two developmental groups: 1) spinal cord and brainstem, 2) telencephalon, cerebellum, DRG and hypothalamus. We obtained an optimized linear mixed model using an EM algorithm. This model will provide a translational method between rodents’ and human’s developmental stages, which can be extremely useful when designing animal studies and clinical tests.

Developmental processes are programmed to occur at specific times within individual progenitor cells20. Because the timing of developmental events in each brain region can be predicted for rats from human data, using a linear regression model, the majority of developmental timings may be governed by a cell-autonomous mechanism. However, the time-keeping mechanism underlying the comparable developmental paces of mutually separated regions (e.g. the cerebral cortex and cerebellum) remains unknown. An analysis of the spatiotemporal transcriptome21 of the brain may reveal that mechanism in future studies.

Previous studies did not identify regional differences in developmental paces6, which can be explained by the method of clustering. In the present study, we classified the brain regions using an optimization method. In contrast, in previous studies5,6,7, the limbic system, which includes a broad brain region, was used for analysis. However, developmental paces differed between the brainstem and telencephalon, which indicates that our translational model is better than those previously established because the limbic system consisted of the part of brainstem (the locus ceruleus and raphe), allocortex (hippocampus and amygdala) and hypothalamus in the previous study6.

Our model is limited in the human foetal period because the relative developmental pace of postnatal human to rat, estimated previously using the synaptic protein development in visual cortex from birth to adult22, was seven-fold slower than the developmental pace of prenatal human to rat in the present study. We removed a few developmental events from our analysis because there were large discrepancies among studies, and we could not determine the precise timing in human (e.g., the onset of olfactory marker protein and the onset of parvalbumin-immunoreactive neurons in the visual cortex). There were a few developmental events for which comparable events could not be identified in rodent (e.g. calcium-binding protein in the inferior olive complex and the onset of synaptophysin in the lateral tuberal hypothalamic nucleus). There were several developmental events we could not use, especially during postnatal development in rat, due to unacceptably large observation error because the interval of juvenile rat age was frequently set to 1 week (e.g. onset of myelination). Developmental events during late gestation had a strong impact on the current results. However, such events were difficult to obtain. Because interactions between different brain regions frequently occur during late gestation, such developmental events may be difficult to translate using our model. Moreover, the chemical cues used in this study were not always cell-type specific markers. We could not rule out the possibility that environmental factors, inter-individual differences and several observation errors due to inter-species differences in the sensitivity of chemical cues affected results. Additional data and further clarification are required in the future. Despite these limitation, our model provides useful information for designing clinical tests on prenatal humans based on rodent data.

Methods

Survey of developmental timings

We first conducted an extensive survey on the developmental changes of the human nervous system using the published literature because human data are less abundant than rodent data. We did not use quantitative data because these are difficult to obtain with high accuracy in humans. To classify developmental events by brain regions, the developmental origins must be clearly determined. To discern cell types and developmental origins, our analysis was focused on the onset of chemical markers. We excluded developmental morphological change (i.e. growth of brain region, or synapse formation) from our analysis, if the cell types related with each developmental event could not be identified. As a next step, we searched the literature for comparable developmental sequences with corresponding onsets in the rat brain because availability of comparable developmental events is the highest in rats. No animals were sacrificed in our study. When comparable developmental events could not be identified for rats, we used the corresponding mice data translated by Clancy et al.5 In such cases, we confirmed the accuracy of mapping by comparing the timing of several developmental events between rats and mice. The translation equation5 was represented by the following linear regression model: rat_day = 1.24 × mouse_day − 1.26. To reduce the measurement error, we restricted events so that the accuracy of onset was less than 3 weeks in humans and 3 days in rats.

To determine the postconceptional day (pcd), we defined the day of insemination as embryonic day (E) 0 in rodents, and whenever the literature used a different method, it was converted into our definition. Postnatal day (P) 0 was defined as E22 for rats. For human, we converted the postconceptional week (pcw) from the gestational week, which was calculated according to the last menses day23.

To investigate the developmental paces of each brain region, we subdivided the collected developmental events into the following according to developmental origin: ‘spinal cord’, ‘DRG’, ‘medulla/pons’, ‘cerebellum’, ‘midbrain’, ‘thalamus’, ‘hypothalamus’, ‘subcortex’ (including the basal forebrain and the basal ganglia), ‘allocortex’ (including the hippocampus, amygdala and olfactory bulb), ‘isocortex’ (including the neocortex), ‘retina’ and ‘other’. We determined the region based on the soma position. When the soma position could not be identified, we selected the most plausible position according to the chemical cues. We did not classify the brain regions by functional system (e.g. visual, somatosensory and limbic) because such a classification was not fully supported by molecular mechanisms.

Model selection

We created a linear mixed model to predict the developmental timings in rats (pcd) based on human developmental timings (pcw). First, we set a group number. Next, the brain regions were classified into one of the groups. The clustering was optimized by an EM algorithm14. Because EM algorithms are sensitive to starting values, we randomly searched the best starting values 10,000 times using an AIC criterion13. We repeatedly optimized the linear mixed model until the best group number was obtained by an EIC criterion14.

Bootstrapping

We repeatedly resampled n developmental events from each group 1,000 times and calculated the regression slope and the estimated timing of neural tube closure. We set n to equal the number of data in each group. We conducted a bootstrap hypothesis test following the guidelines23. We did not assume equal variances among compared variables. Estimated variances were obtained using an inner bootstrap loop with 50 bootstrap samples. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05. Multiple comparisons were adjusted by the Benjamini–Hochberg method18.

Data Availability

All data analysed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

References

Kinney, D. K., Munir, K. M., Crowley, D. J. & Miller, A. M. Prenatal stress and risk for autism. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 32, 1519–1532 (2008).

Gluchman, P. D., Hanson, M. A., Buklijas, T., Low, F. M. & Alan, S. B. Epigenetic mechanisms that underpin metabolic and cardiovascular diseases. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 5, 401–408 (2009).

Hubel, D. H. & Wiesel, T. N. The period of susceptibility to the physiological effects of unilateral eye closure in kittens. J. Physiol. 206, 419–436 (1970).

Robinson, R. S. & Dreher, B. The visual pathways of eutherian mammals and marsupials develop according to a common timetable. Brain Behav. Evol. 36, 177–195 (1990).

Clancy, B., Darlington, R. B. & Finlay, B. L. Translating developmental time across mammalian species. Neuroscience 105, 7–17 (2001).

Workman, A. D., Charvet, C. J., Clancy, B., Darlington, R. B. & Finlay, B. L. Modeling transformation of neurodevelopmental sequences across mammalian species. J. Neurosci. 33, 7368–7383 (2013).

Finlay, B. L. & Darlington, R. B. Linked regularities in the development and evolution of mammalian brains. Science 268, 1578–1584 (1995).

Kayser, M. S., Yue, Z. & Sehgal, A. A critical period of sleep for development of courtship circuitry and behavior in Drosophila. Science 344, 269–274 (2014).

Whiteus, C., Freitas, C. & Grutzendler, J. Perturbed neural activity disrupts cerebral angiogenesis during a postnatal critical period. Nature 505, 407–411 (2013).

Orefice, L. L. et al. Peripheral mechanosensory neuron dysfunction underlies tactile and behavioral deficits in mouse model of ASDs. Cell 166, 299–313 (2016).

Duerksen, K., Barlow, W. E. & Stasior, O. G. Fused eyelids in premature infants. Ophthal. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 10, 234–240 (1994).

De Veux, R. D. Mixtures of linear regressions. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 8, 227–245 (1989).

Akaike, H. A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans. Automat. Contr. 19, 716–723 (1974).

Ishiguro, M., Sakamoto, Y. & Kitagawa, G. Bootstrapping log likelihood and EIC, an extension of AIC. Ann. Inst. Statist. Math. 49, 411–434 (1997).

Dempster, A. P., Laird, N. M. & Rubin, D. B. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data via the EM algorithm. J. R. Stat. Soc. Series B Stat. Methodol. 39, 1–38 (1977).

Efron, B. Bootstrap methods: another look at the jackknife. Ann. Stat. 7, 1–26 (1979).

Hall, P. & Wilson, S. R. Two guidelines for bootstrap hypothesis testing. Biometrics 47, 757–762 (1991).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Statist Soc Ser.B 57, 298–300 (1995).

O’Rahilly, R. & Müller, F. The two sites of fusion of the neural folds and the two neuropores in the human embryo. Teratology 65, 162–170 (2002).

Otani, T., Marchetto, M. C., Gage, F. H., Simons, B. D. & Livesey, F. J. 2D and 3D stem cell models of primate cortical development identity species-specific differences in progenitor behavior contributing to brain size. Cell Stem Cell 1, 467–480 (2016).

Kang, H. J. et al. Spatio-temporal transcriptome of the human brain. Nature 478, 483–489 (2011).

Pinto, J. G. A., Jones, D. G., Williams, C. K. & Murphy, K. M. Characterizing synaptic protein development in human visual enables alignment of synaptic age with rat visual cortex. Front. Front. Neural Circuits 9, 3 (2015).

Engle, W. A. Age terminology during the perinatal period. Pediatrics 114, 1362–1364 (2004).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to K Nakajima and A Arata for their comments during the preparation of this paper. This work was supported by a MEXT Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas-‘Constructive Developmental Science’ 24119002.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.O. designed and conducted the experiments. Y.O. and Y.K. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ohmura, Y., Kuniyoshi, Y. A translational model to determine rodent’s age from human foetal age. Sci Rep 7, 17248 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17571-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17571-z

This article is cited by

-

Divergent Pattern of Development in Rats and Humans

Neurotoxicity Research (2024)

-

Single-cell transcriptomic landscape of the developing human spinal cord

Nature Neuroscience (2023)

-

The development of descending serotonergic modulation of the spinal nociceptive network: a life span perspective

Pediatric Research (2022)

-

Microglia and Stem-Cell Mediated Neuroprotection after Neonatal Hypoxia-Ischemia

Stem Cell Reviews and Reports (2022)

-

Early life stress alters transcriptomic patterning across reward circuitry in male and female mice

Nature Communications (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.