Abstract

Long-term headache attacks may cause human brain network reorganization in patients with migraine. In the current study, we calculated the topologic properties of functional networks based on the Brainnetome atlas using graph theory analysis in 29 female migraineurs without aura (MWoA) and in 29 female age-matched healthy controls. Compared with controls, female MWoA exhibited that the network properties altered, and the nodal centralities decreased/increased in some brain areas. In particular, the right posterior insula and the left medial superior occipital gyrus of patients exhibited significantly decreased nodal centrality compared with healthy controls. Furthermore, female MWoA exhibited a disrupted functional network, and notably, the two sub-regions of the right posterior insula exhibited decreased functional connectivity with many other brain regions. The topological metrics of functional networks in female MWoA included alterations in the nodal centrality of brain regions and disrupted connections between pair regions primarily involved in the discrimination of sensory features of pain, pain modulation or processing and sensory integration processing. In addition, the posterior insula decreased the nodal centrality, and exhibited disrupted connectivity with many other brain areas in female migraineurs, which suggests that the posterior insula plays an important role in female migraine pathology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Migraines represent a recurrent and disabling neurological disorder associated with a combination of nausea, vomiting, tiredness, phonophobia, and photophobia, etc1. Migraines have become a major public health concern and plague nearly one in nine adults worldwide2. The prevalence of female migraineurs is two to three times that of male migraineurs, and females tend to require a longer time to recover and experience a longer attack duration, greater disability, and increased risk of headache recurrence3,4. Many neuroimaging studies have employed functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which provides a feasible, efficient and noninvasive tool to investigate the pathophysiological mechanisms of migraine. fMRI has revealed various dysfunctional brain areas in migraine mainly distributed in the the salience network, default mode network, the sensorimotor network, and the executive control network5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15. Our group recently investigated the abnormal patterns of functional networks of migraine compared with controls and found that migraineurs without aura (MWoA) showed the default mode network and sensorimotor network dysfunction12,15. However, these studies primarily focused on local dysfunction of brain regions or single intrinsic brain networks and neglected the information of connectome-scale aspect.

The human brain is a complex system that can be modeled as an extremely complex network consisting of edges (connections between pair regions) and nodes (brain areas)16,17,18. Graph theory analysis was a useful method for researching the functional integration and segregation patterns of brain networks and to investigate both global and local metrics. Previous brain network studies based on the Automated Anatomic Labeling (AAL) atlas have suggested that migraineurs exhibit alterations of topological properties and long-term headache attacks may cause human brain network reorganization in migraineurs19,20,21,22. Liu et al. found gender-related changes in the topological properties of functional networks and suggested that the networks of females may be more vulnerable to migraine19, finding hierarchical changes of structural and functional networks in female migraineurs20.

Previous research have shown that females are more likely to have migraine than males4, and the functional networks of females may be more vulnerable to migraine19, suggesting that the function and structure of the insula may be altered in migraine, especially in female migraineurs23,24. The female migraineurs showed a lack of thinning in the insula with age in contrast to healthy subjects24. In addition, female migraineurs exhibited increased cortical thickness in the posterior insular cortices compared with male patients with migraine and healthy controls23. The insula has been found to exhibit reductions in gray matter volume25, and function abnormal activation during the processing of pain-related words26, and aberrant connection with other regions10,27,28,29,30, which indicate that the insula structure and function are altered in migraine31. In fact, the insula was proposed as a “hub of activity” in migraine, as it processes and relays afferent inputs from frontal, temporal and parietal regions31. There are several functionally distinct areas within the insula: the posterior insula is mainly involved in somatosensory processes, the anterior insula in cognitive function, and the inferior insula in chemical sensory and social-emotional function32,33,34. A previous study using a region-of-interest analysis and task-free fMRI reported that the anterior insula increased intrinsic connectivity in migraine without aura29. The dorsal posterior insular cortex has been demonstrated to play a fundamental role in human pain35. However, the insula has not been reported to be abnormal in previous graph theory studies based on the AAL atlas19,20,21,22, which may be due to its coarse sub-regions. Notably, the AAL atlas was acquired according to the anatomical sulcal information of brain of a single person, and it may be not suitable for group-level analysis because of individual differences in anatomical structure36,37. Recently, a more precise atlas, the Brainnetome atlas, with 36 subcortical subregions and 210 cortical was designed based on 40 healthy adults using noninvasive multimodal neuroimaging techniques and is freely available for download by researchers38. More importantly, the insula is divided into 12 subregions in the Brainnetome atlas. Thus, we think that the Brainnetome atlas could detect the local abnormal or the disrupted functional connectivity of the sub-regions of insula in migraineurs, and the functional changes of insula may be involved in its structural alterations.

Hence, graph theory analysis based on the Brainnetome atlas was used to explore and investigate the topological organization of the functional networks of female MWoA, and we compared the differences in topological organizations of networks constructed by the AAL atlas and the Brainnetome atlas. Subsequently, the volumetric analysis in brain regions with nodal centrality alterations were used to investigate the corresponding structural changes. We hypothesized that the topological properties of functional networks, the functional connectivity patterns and the volume of the insular sub-regions would be altered in female MWoA.

Methods

The Independent Ethics Committee of Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital (Project No. [2016]01) and East China Normal University Committee on Human Research (Project No. HR2016/03022) approved the current study. All subjects were asked to provide written informed consent, which was approved by the committee. All methods were carried out in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, including any relevant details.

Subjects

Twenty-nine female MWoA (age ± SD, 40.1 ± 11.4) were recruited from among outpatients of the Department of Neurology at Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital. According to the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-III beta, 2013), the headache patients were diagnosed as MWoA by a neurologist. MWoA were excluded from our study according to the following criteria: 1) patients who suffered a headache attack during 48 h before MRI scans; 2) patients who suffered from a migraine attack or who felt discomfort during the MRI scans; and 3) patients who were taking preventive medicines or with a chronic migraine. Twenty-nine female age-matched healthy controls (age ± SD, 39.8 ± 11.2) were recruited. The control subjects had not suffered headaches in the past year, and their immediate family members had not been diagnosed with migraines. According to structured interviews and clinical examinations, all participants had not suffered any neurological or psychiatric diseases, were free of substance abuse, and were right handed. The clinical data and demographics of the patients and controls are presented in Table 1.

MRI acquisition

T1-weighted data with high-resolution and resting-state fMRI data were obtained from a 3 T Siemens scanner (Trio Tim, Germany) with a 12-channel head coil. To minimize head motion, custom-fit foam pads were used to fix the head of subjects. T1-weighted data with high-resolution were obtained using a 3-dimensional magnetization-prepared rapid-acquisition gradient-echo pulse sequence with the following parameters: 192 slices, matrix size = 256 × 256, field of view = 256 × 256 mm2, echo time = 2.34 ms, repetition time = 2530 ms, inversion time = 1100 ms, and slice thickness = 1 mm. The fMRI images were acquired using a T2*-weighted gradient-echo echo-planar imaging pulse sequence, with the following parameters: 210 volumes, transverse orientation, matrix size = 64 × 64, field of view = 220 × 220 mm2, echo time = 30 ms, repetition time = 2000 ms, 33 slices, 25% Dist factor, slice thickness = 3.5 mm, and flip angle = 90°. The patients and controls were instructed to remain still, close their eyes, and relax during the fMRI scan.

Data preprocessing

Resting-state fMRI images preprocessing was performed with SPM 12 software (Statistical Parametric Mapping; http://www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/). The main processes were as follows: 1) To ensure that the participants adapted to the scanner noise and to avoid scanner instability, the first ten volumes were removed from the fMRI images. 2) Slice timing was conducted to correct the time delay of intra-volume acquisition. 3) Using rigid body (six parameters) spatial transformation, the fMRI data were realigned to the first volume. 4) The T1-weighted images were coregistered to the mean functional images. 5) The T1-weighted data were segmented into white matter and gray matter, and the forward deformation fields and the inverse deformation fields were generated using the “New Segment” method. 6) Spatial normalization was performed to register the functional images to the MNI space, and images were resampled to 3 mm × 3 mm × 3 mm. 7) The normalized images were spatially smoothed with a 4-mm full-width half-maximum (FWHM) Gaussian filter. 8) The linear trend of the smoothed images was removed, and the signals of the cerebrospinal fluid, the white matter and six parameters of head motion were regressed out as covariates. 8) To reduce the influence of high-frequency respiratory and cardiac noise and low-frequency drift, the data were temporally bandpass filtered (0.01 < f < 0.1 Hz).

In the current study, none of he subjects were excluded, as the maximum rotation movement was <2° and the translation movement was < 2 mm for all subjects. We compared head motion parameters in any direction between the control and migraine groups using a nonparametric permutation test (50000 permutations) and we did not find any significant difference (pitch, p = 0.72; roll, p = 0.57; yaw, p = 0.72; x, p = 0.37; y, p = 0.30; z, p = 0.19).

Network construction and analysis based on the Brainnetome atlas

We constructed the functional network with the graph theoretical network analysis (GRETNA) toolbox39. The human Brainnetome atlas38 was employed to define the brain nodes, and each brain area represents a node of the network (Supplementary Table S1). The average time series was generated from the human Brainnetome atlas. Finally, these time series were used to calculate the correlation coefficient using Pearson correlation, and 246 × 246 correlation matrices for participants were generated for graph theory analysis.

To address the differences in the number of edges within subjects, a range sparsity threshold S (0.10 ≤ S ≤ 0.30, interval 0.01) were applied to all network matrix. We defined sparsity as the actual number of edges of a specific network divided by the maximum possible number of edges40. The range of S which was chosen to ensure that each thresholded network had small-worldness (σ > 1.1) and the mean degree of all brain areas for each thresholded network was greater than 2 × log (246), and was consistent with previous studies41,42. For functional network at each sparsity threshold, a binary matrix was generated from the correlation matrix if the positive correlation values between two brain regions exceeded a given sparsity threshold, and then, both the global and nodal measures of all networks were calculated.

We calculated the small-world parameters, network efficiency and nodal centrality as follows: (1) small-world parameters: characteristic path length (Lp), clustering coefficient (Cp), normalized characteristic path length (λ), normalized clustering coefficient (γ), and small-worldness (σ); (2) network efficiency: global efficiency (Eglob) and local efficiency (Eloc); (3) nodal centrality: nodal betweenness, efficiency and degree42,43,44. The definitions of network measures are presented in Supplementary Table S2. Furthermore, the areas under the curve (AUC) for each network metric (Y) were calculated as:

In the current study, S1 = 0.10, Sn = 0.30, and ΔS = 0.01 (Fig. 1). The AUC metric provides a summarized measure for the global and local parameters of functional networks rather than a single threshold selection and is sensitive to detecting topological changes in neurological disorders, as previously reported41,45.

Network construction and analysis based on the AAL atlas

We also constructed functional networks based on Automated Anatomical Labeling37 and calculated the global metrics (Lp, Cp, λ, γ, σ, Eglob, Eloc) and nodal centrality (the nodal betweenness, efficiency and degree) according to the above methods.

Statistical analysis

We compared the AUC of each network metric, including small-world properties (Lp, Cp, λ, γ, σ), network efficiency (Eglob, Eloc) and nodal characteristics (nodal betweenness, efficiency and degree), between female MWoA and healthy controls using nonparametric permutation tests. First, the difference in the average value of each metric between groups was calculated. Then, we randomly reassigned all the values of each metric into two groups and recalculated the difference in the average value of each metric between the two randomized groups. Finally, we repeated the randomization procedure 50,000 times to obtain probability distributions. We used false discovery rate (FDR) correction to address the problem of multiple comparisons(P < 0.05).

Moreover, the nonparametric permutation test (50000 permutations) was used to localize the functional connectivity that significantly changed in the large-scale brain networks of female MWoA compared with healthy controls using the NBS connectome toolbox (version 1.2)46. FDR correction was used to address the problem of multiple comparisons (P < 0.01).

Volumetric analysis

The inverse deformation field were generated from previous preprocessing procedure. Then, the Brainnetome atlas were projected onto the individual space by applying the inverse deformation field, which would construct the individual Briannetome atlas. We calculated the subject-specific volume of brain regions with nodal centrality changes (FDR corrected), and then computed the ratio of brain region volume/total gray matter volume to eliminate the differences of total gray matter volume of subjects. Finally, the corrected volumetric differences were compared between migraine patients and controls using the nonparametric permutation test (50000 permutations).

Correlation analysis

The values of significant alterations in the global and nodal characteristics were correlated with the clinical data of migraineurs using Pearson correlation analysis, including attack frequency, attack duration, and disease duration, as well as the Headache Impact Test (HIT-6), Migraine Disability Assessment Scale (MIDAS) scores and visual analogue scale (VAS). Significant correlations were determined based on uncorrected p-values(p < 0.05).

Results

Global and reginal topological organizations of the functional networks based on the Brainnetome atlas

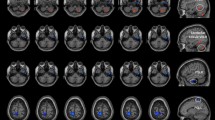

The functional networks of female MWoA and healthy controls had higher clustering coefficients (Cp) and similar characteristic path lengths (Lp) than the random networks, which indicated that both female MWoA and healthy controls exhibited typical small-world topology properties. The female MWoA exhibited significantly lower Cp and Eloc values and higher γ and σ values (P < 0.05, uncorrected, nonparametric permutation test) than the control group. There were no differences in Lp, λ, and Eglob between the healthy controls and female MWoA. The details are presented in Fig. 2.

The differences in the topological organizations of brain networks based on the Brainnetome atlas between female MWoA and healthy controls. Error bars denote standard deviations. *Significant difference between two groups (P < 0.05, uncorrected, 50000 permutations test); HC: healthy controls; FM: female MWoA; Eglob: global efficiency; Eloc: local efficiency; Lp: characteristic path length; λ: normalized characteristic path length; Cp: clustering coefficient; γ: normalized clustering coefficient; σ: small-worldness.

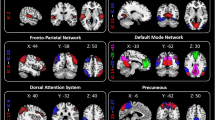

We report the brain regions exhibiting significant differences between groups in at least one nodal metric. The right posterior insula (hypergranular insula) and the left medial superior occipital gyrus of female MWoA had significantly decreased nodal centrality compared with healthy controls (P < 0.05, FDR corrected, nonparametric permutation test). We also report the brain regions exhibiting significant differences between groups in uncorrected level (P < 0.005, uncorrected, nonparametric permutation test). Compared with healthy controls, female MWoA exhibited decreased nodal centralities in the left precentral gyrus (BA 4, upper limb region), the right paracentral lobule, the right parahippocampal gyrus, the bilateral superior parietal lobule (postcentral BA7), the right posterior insula (hypergranular insula), the left occipital cortex (ventromedial parietooccipital sulcus, middle and medial-superior occipital gyrus) and the right thalamus (sensory thalamus) (P < 0.005, nonparametric permutation test, uncorrected). The female MWoA exhibited increased nodal centralities in the bilateral superior frontal gyrus (medial BA 9 and medial BA 10), the right middle frontal gyrus (dorsal BA 9/46), the right inferior frontal gyrus (rostral BA 45), the left inferior temporal gyrus (caudolateral and rostral BA 20, ventrolateral BA 37), the bilateral inferior parietal lobule (rostroventral BA 39 and caudal BA 40), and the right occipital polar cortex (P < 0.005, nonparametric permutation test, uncorrected). The details are presented in Fig. 3 and Table 2.

Subregions of the brain within the Brainnetome atlas showing abnormal nodal centrality in female MWoA compared with healthy controls. Compared with healthy controls, the MWoA showed decreased (blue color) nodal centralities in the precentral gyrus (BA4), the right parahippocampal gyrus, the left paracentral lobule, the bilateral superior parietal lobule (BA7), the right posterior insula, the left occipital cortex and the sensory thalamus. The migraineurs showed increased (red color) nodal centralities in the PFC (left BA9, right BA9/10/45/47), the bilateral inferior parietal lobes (left BA40 and right BA39), the left inferior temporal gyrus (BA20/37) and the right occipital polar cortex.

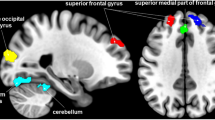

Disrupted functional connectivity in female MWoA

We identified a disrupted or altered network with 61 connections within 54 sub-regions, and these connections were significantly decreased in female MWoA compared with controls (P < 0.01, FDR corrected, nonparametric permutation test) (Fig. 4). No increased connections were detected in MWoA. The sub-regions and disrupted connections were distributed in different lobes, including the orbital frontal cortex, the sensory-motor cortex, the inferior frontal gyrus, the cingulate cortex, the parietal lobe, the temporal lobe, the insular cortex, the occipital lobe and the subcortical nuclei (Fig. 4).

The disrupted connections within the brain network in female MWoA compared with healthy controls. The nodes were primarily located in the orbital frontal cortex, the sensory-motor cortex, the inferior frontal gyrus, the temporal lobe, the cingulate cortex, the posterior parietal lobe, the insular cortex, the occipital lobe and the subcortical nuclei. IFG: inferior frontal gyrus; OrG: orbital frontal gyrus; PrG: precentral gyrus; PCL: paracentral gyrus; STG: superior temporal gyrus; MTG: middle temporal gyrus; FuG: fusiform gyrus; PhG: parahippocampal gyrus; SPL: superior parietal lobule; IPL: inferior parietal gyrus; Pcun: precuneus; PoG: postcentral gyrus; CG: cingulate gyrus; MVOcC: medio ventral occipital cortex; LOcC: lateral occipital cortex; Hipp: hippocampus; BG: basal ganglia; Tha: thalamus.

Volumetric analysis

The volumetric analysis were performed in the posterior insula (INS_R_6_1) and the left medial superior occipital gyrus (LOcC _L_2_1) which exhibited the nodal centrality changes. The results exhibited that the posterior insula in female MWoA was significantly smaller than healthy controls (p = 0.049, uncorrected), and the left medial superior occipital gyrus showed no differences between groups. The details are presented in Table 3.

Correlation with clinical scores

We found that Eloc (p = 0.023, r = −0.422, uncorrected) and Cp (p = 0.016, r = −0.444, uncorrected) in female MWoA were negatively correlated with the MIDAS score (Fig. 5). However, the other altered global and nodal characteristics were not significantly correlated with attack duration, disease duration, attack frequency, or the VAS and HIT-6 scores in the female MWoA.

Global and regional topological organizations of the functional networks based on the AAL atlas

Upon analyzing the functional networks constructed by the AAL atlas, we only found that γ (P = 0.037) and σ (P = 0.028) of female MWoA were significantly increased compared with controls (Supplementary Figure S1). In addition, nodal centrality was significantly increased in the bilateral medial prefrontal cortex, the right orbital frontal cortex, the right posterior cingulate gyrus and the left inferior temporal gyrus and decreased in the left precentral gyrus, the left orbital frontal cortex, the left superior and middle occipital gyrus, the left postcentral gyrus, and the left pallidum (P < 0.005, nonparametric permutation test, uncorrected). The details are presented in Supplementary Figure S2 and Table S3.

Discussion

In the current study, we calculated the small-world topology properties of networks based on the Brainnetome atlas and found that female MWoA exhibited significantly higher γ and σ values and lower Cp and Eloc values compared with controls (Fig. 2). The Cp and Lp of a network reveal the ability of functional segregation and integration, respectively44. More specifically, the brain’s functional segregation is the ability for specific processing within densely interconnected clusters of brain areas, and the brain’s integration is the ability to rapidly transfer and integrate specialized information from different brain areas44. The Eglob and Eloc of a graph measure the global and local efficiency of information, while λ, γ and σ reflect the small-worldness of a functional network47. The significantly lower Cp and Eloc values may suggest that the brain network of MWoA corresponded to decreased functional segregation that affected the local efficiency of information processing. In addition, Cp and Eloc in patients with migraine were negatively correlated with the MIDAS score (Fig. 5), which suggested that the topology properties of network alteration may be associated with the daily life of the patient and the pathophysiology of migraine. Conversely, the higher γ and σ in migraineurs may enhance the network’s small-worldness. The alterations in the small-world measures and network efficiency may be caused by alterations of the nodal centrality of specified brain areas that are involved in pain processing or modulation.

Nodal centrality, which is measured by nodal degree, efficiency and betweenness, is an important index for evaluating the importance of nodes within functional networks. The changes in nodal centrality for individual brain regions may affect the information processing efficiency and the functional integration or segregation of the functional network. In the current study, female migraineurs exhibited decreased nodal centralities in the precentral gyrus (BA4), the right parahippocampal gyrus, the left paracentral lobule, the bilateral superior parietal lobule (BA7), the right posterior insula, the left occipital cortex and the sensory thalamus compared with healthy controls (Fig. 3). The female migraineurs also showed increased nodal centralities in the PFC (left BA9, right BA9/10/45/47), the left inferior temporal gyrus (BA20/37), the bilateral inferior parietal lobes (left BA40 and right BA39) and the right occipital polar cortex(Fig. 3). These brain regions are involved in discrimination of sensory features of pain, and pain processing or modulation13,31,48,49,50,51. The prefrontal cortex has been shown to receive sensory information from pain-associated cortical areas (SI, ACC, SII/insula and thalamus) and plays an important role in cognitive modulation of pain52. The alterations of the prefrontal cortex in migraineurs are consistent with anatomical and functional changes reported in previous studies12,53,54,55,56. It has been proposed that the inferior and superior parietal lobules and the anterior cingulate cortex are involved in the spatial discrimination about sensory features of pain, and the bilateral dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the insula are associated with intensity discrimination of sensory features of pain48,49,51. The temporal lobe is associated with multimodal sensory integration and has been demonstrated to be activated during migraine attacks and pain experiences57,58. A previous graph theory study of migraineurs found altered nodal efficiency of the prefrontal cortex, the insula and the paracentral lobule in structural networks based on the AAL atlas21. Thus, the nodal centrality alterations are in line with previous research and may affect the pathway of pain processing or modulation and even affect functional integration or segregation processing of the functional network in MWoA. Figure 3 shows that brain regions with increased and decreased nodal centrality coexist in female MWoA. We suppose that the brain regions with decreased nodal centrality may disrupt the pathway of pain processing or modulation, and conversely, the brain regions with increased nodal centrality may have compensatory functions or induce migraine patients to be more sensitive to pain50,59.

Furthermore, we identified a disrupted network with 61 connections within 54 nodes in the MWoA, and these nodes exhibited decreased connections distributed to different lobes, including the orbital frontal cortex, the sensory-motor cortex, the inferior frontal gyrus, the cingulate cortex, the posterior parietal lobe, the temporal lobe, the insular cortex, the occipital lobe and the subcortical nuclei (Fig. 4). In particular, the right posterior insula and the right parahippocampal gyrus exhibited disrupted connectivity with many of brain regions (Fig. 4). The subregions of the brain with disrupted connectivity in patients were involved in the discrimination of sensory features of pain (sensory-motor cortex, posterior insula and posterior parietal cortex), cognitive processing (orbitofrontal cortex and parahippocampal gyrus), pain modulation processing (thalamus, insula, anterior cingulate cortex, and prefrontal cortex), sensory integration processing (temporal lobe) and visual information processing (occipital lobe)26,31,48,49,51,55,60,61,62,63,64. The parahippocampal gyrus exhibited disrupted connectivity with the fusiform gyrus, the temporal lobe, the occipital lobe and the parietal lobe. These results are in line with previous research that also investigated abnormal nodal centrality in both functional and structural networks in the parahippocampal gyrus19,20,22. In our results, these decreased connections may result in dysfunction of pain processing and reorganization of the functional networks in female MWoA.

Figures 3 and 4 show that the posterior insula exhibited significantly decreased nodal centrality and the two subregions of the right posterior insula exhibited decreased connectivity with many of brain regions in female MWoA. The insula is a hub region of the brain, and its function is associated with goal-directed cognition, conscious awareness, autonomic regulation, interoception, and somatosensation31,65. The insular cortices has been proposed as “a multidimensional integration site for pain”66. The posterior insular cortices is connected to the premotor, middle-posterior cingulate, supplementary motor and sensorimotor cortices, indicating its role in sensorimotor integration28,32,33,34, and it has been proposed to play a fundamental role in human pain35. The insula has been proposed as a “hub of activity”, as it is connected to frontal, temporal and parietal regions and processes many aspects of complex emotional, cognitive and sensory functions in migraine31. Ferot et al. investigated the timing of activations across the different sub-regions of insular cortices using intracerebrally recorded nociceptive laser-evoked potentials (LEPs). The results suggested that the posterior insula, which is associated with coding intensity and anatomical location, first processes nociceptive input and then conveys the nociceptive information to the anterior insula, which is related to the processing of the emotional reactions for pain67, indicating that the posterior insular cortices is associated with pain perception. Numerous migraine studies have reported that the insula changes structural, functional, and aberrant connections to other regions10,11,23,26,27,28,29,30,60,68,69. In addition, we found that the insula was abnormal in right hemisphere. Right-sided lateralization of the insula has also been observed in a number of studies of pain and migraine24,70,71. In line with this research, our previous study found that MWoA exhibit significantly decreased cortical thickness in the right insular cortex using surface-based morphometry. It is noteworthy that the volume of posterior insula in female MWoA was smaller compared with healthy controls in current study. Previous findings have suggested that brain function is closely related to anatomical structure72,73. Thus, nodal centrality alterations of the insula in female MWoA may be associated with structure changes and the causality of functional and structural changes in posterior insula should be further investigated. In conclusion, female MWoA exhibited decreased nodal centrality and disrupted functional connectivity in the posterior insula, which suggests that female MWoA may exhibit dysfunction of pain processing and perception and that the posterior insula plays an important role in female migraine pathology.

In most previous studies, functional networks were generated at coarse regional level by segmenting the entire brain into 90 sub-regions based on anatomical sulcal information. It has been demonstrated that the different parcellation atlases may result in different topological properties36,74. Fan et al. designed a human Brainnetome atlas that identified subdivisions of the whole brain (36 subcortical and 210 cortical subregions) based on connectivity parcellation38. In this study, we constructed the functional network using a precise connectivity-based parcellation atlas (Brainnetome atlas), and we also compared the differences in topological organizations of networks constructed by the AAL and the Brainnetome atlas. We found that σ and γ of the brain networks of migraineurs were significantly greater than those of controls based on both the AAL and Brainnetome atlas (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Figure S1). However, the nodal centrality of networks based on the AAL atlas showed that many brain regions overlapped with the Brainnetome atlas, including the precentral gyrus, the inferior temporal gyrus, the occipital cortex and the medial prefrontal cortex. In addition, the nodal centrality of networks based on the Brainnetome atlas showed more abnormal brain regions, including the posterior insula, the paracentral lobule, the inferior frontal gyrus, the inferior and superior parietal lobule, the sensory thalamus and the parahippocampus, than the networks based on the AAL atlas. Thus, our results suggest that the different parcellation atlases may result in different topological properties, and the Brainnetome atlas could detect some subtle changes of brain regions and would be complement of structural atlas (e.g. AAL).

The current study sought to investigate the functional network topologic properties of female MWoA based on a precise parcellation atlas (Brainnetome atlas) using graph theory analysis. We found that the topological properties of functional networks in patients were altered compared with controls. The brain regions with changed nodal centrality and disrupted connections were those primarily involved in pain perception, pain modulation or processing and sensory integration processing. Thus, our results may reflect brain network dysfunction or reorganization in female MWoA, which may affect information transmission of pain and pain modulation processing in MWoA. Notably, the posterior insula exhibited decreased nodal centrality, smaller volume and disrupted connectivity with many other brain areas in female migraineurs, which suggests that the posterior insula may be associated with the structural alterations and plays an important role in female migraine pathology. Although all female MWoA were recruited for the current study based strictly on the ICHD-III beta, the clinical heterogeneity of the patient is a primary limitation of this research. Thus, the results of this study should be further validated.

References

Headache Classification Subcommittee of the International Headache, S. The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Cephalalgia: an international journal of headache 24(Suppl 1), 9–160 (2004).

Stovner, L. et al. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia: an international journal of headache 27, 193–210, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01288.x (2007).

Steiner, T. J., Stovner, L. J. & Vos, T. GBD 2015: migraine is the third cause of disability in under 50s. The journal of headache and pain 17, 104, https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-016-0699-5 (2016).

Vetvik, K. G. & MacGregor, E. A. Sex differences in the epidemiology, clinical features, and pathophysiology of migraine. The Lancet. Neurology 16, 76–87, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(16)30293-9 (2017).

Jin, C. et al. Structural and functional abnormalities in migraine patients without aura. NMR Biomed 26, 58–64, https://doi.org/10.1002/nbm.2819 (2013).

Mainero, C., Boshyan, J. & Hadjikhani, N. Altered functional magnetic resonance imaging resting-state connectivity in periaqueductal gray networks in migraine. Annals of neurology 70, 838–845, https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.22537 (2011).

Tessitore, A. et al. Abnormal Connectivity Within Executive Resting-State Network in Migraine With Aura. Headache 55, 794–805, https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12587 (2015).

Russo, A. et al. Executive resting-state network connectivity in migraine without aura. Cephalalgia: an international journal of headache 32, 1041–1048, https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102412457089 (2012).

Tessitore, A. et al. Disrupted default mode network connectivity in migraine without aura. The journal of headache and pain 14, 89, https://doi.org/10.1186/1129-2377-14-89 (2013).

Xue, T. et al. Intrinsic brain network abnormalities in migraines without aura revealed in resting-state fMRI. PloS one 7, e52927, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0052927 (2012).

Zhao, L. et al. Alterations in regional homogeneity assessed by fMRI in patients with migraine without aura stratified by disease duration. The journal of headache and pain 14, 85, https://doi.org/10.1186/1129-2377-14-85 (2013).

Zhang, J. et al. Increased default mode network connectivity and increased regional homogeneity in migraineurs without aura. The journal of headache and pain 17, 98, https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-016-0692-z (2016).

Schwedt, T. J., Chiang, C. C., Chong, C. D. & Dodick, D. W. Functional MRI of migraine. The Lancet. Neurology 14, 81–91, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70193-0 (2015).

Maleki, N. & Gollub, R. L. What Have We Learned From Brain Functional Connectivity Studies in Migraine Headache? Headache 56, 453–461, https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12756 (2016).

Zhang, J. et al. The sensorimotor network dysfunction in migraineurs without aura: a resting-state fMRI study. Journal of neurology, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-017-8404-4 (2017).

He, Y. & Evans, A. Graph theoretical modeling of brain connectivity. Curr Opin Neurol 23, 341–350, https://doi.org/10.1097/WCO.0b013e32833aa567 (2010).

Bassett, D. S. & Bullmore, E. Small-world brain networks. The Neuroscientist: a review journal bringing neurobiology, neurology and psychiatry 12, 512–523, https://doi.org/10.1177/1073858406293182 (2006).

Bassett, D. S. & Bullmore, E. T. Small-World Brain Networks Revisited. The Neuroscientist: a review journal bringing neurobiology, neurology and psychiatry, https://doi.org/10.1177/1073858416667720 (2016).

Liu, J. et al. Gender-related differences in the dysfunctional resting networks of migraine suffers. PloS one 6, e27049, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0027049 (2011).

Liu, J. et al. Hierarchical alteration of brain structural and functional networks in female migraine sufferers. PloS one 7, e51250, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0051250 (2012).

Li, K. et al. Abnormal rich club organization and impaired correlation between structural and functional connectivity in migraine sufferers. Brain imaging and behavior, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11682-016-9533-6 (2016).

Liu, J. et al. Disrupted resting-state functional connectivity and its changing trend in migraine suffers. Human brain mapping 36, 1892–1907, https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.22744 (2015).

Maleki, N. et al. Her versus his migraine: multiple sex differences in brain function and structure. Brain: a journal of neurology 135, 2546–2559, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/aws175 (2012).

Maleki, N. et al. Female migraineurs show lack of insular thinning with age. Pain 156, 1232–1239, https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000159 (2015).

Kim, J. H. et al. Regional grey matter changes in patients with migraine: a voxel-based morphometry study. Cephalalgia: an international journal of headache 28, 598–604, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01550.x (2008).

Eck, J., Richter, M., Straube, T., Miltner, W. H. & Weiss, T. Affective brain regions are activated during the processing of pain-related words in migraine patients. Pain 152, 1104–1113, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2011.01.026 (2011).

Schwedt, T. J. et al. Atypical resting-state functional connectivity of affective pain regions in chronic migraine. Headache 53, 737–751, https://doi.org/10.1111/head.12081 (2013).

Hadjikhani, N. et al. The missing link: enhanced functional connectivity between amygdala and visceroceptive cortex in migraine. Cephalalgia: an international journal of headache 33, 1264–1268, https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102413490344 (2013).

Tso, A. R., Trujillo, A., Guo, C. C., Goadsby, P. J. & Seeley, W. W. The anterior insula shows heightened interictal intrinsic connectivity in migraine without aura. Neurology 84, 1043–1050, https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001330 (2015).

Niddam, D. M. et al. Reduced functional connectivity between salience and visual networks in migraine with aura. Cephalalgia: an international journal of headache 36, 53–66, https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102415583144 (2016).

Borsook, D. et al. The Insula: A “Hub of Activity” in Migraine. The Neuroscientist: a review journal bringing neurobiology, neurology and psychiatry 22, 632–652, https://doi.org/10.1177/1073858415601369 (2016).

Klein, T. A., Ullsperger, M. & Danielmeier, C. Error awareness and the insula: links to neurological and psychiatric diseases. Frontiers in human neuroscience 7, 14, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2013.00014 (2013).

Kurth, F., Zilles, K., Fox, P. T., Laird, A. R. & Eickhoff, S. B. A link between the systems: functional differentiation and integration within the human insula revealed by meta-analysis. Brain structure & function 214, 519–534, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-010-0255-z (2010).

Stephani, C., Fernandez-Baca Vaca, G., Maciunas, R., Koubeissi, M. & Luders, H. O. Functional neuroanatomy of the insular lobe. Brain structure & function 216, 137–149, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-010-0296-3 (2011).

Segerdahl, A. R., Mezue, M., Okell, T. W., Farrar, J. T. & Tracey, I. The dorsal posterior insula subserves a fundamental role in human pain. Nature neuroscience 18, 499–500, https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.3969 (2015).

Wang, J. et al. Parcellation-dependent small-world brain functional networks: a resting-state fMRI study. Human brain mapping 30, 1511–1523, https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20623 (2009).

Tzourio-Mazoyer, N. et al. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. NeuroImage 15, 273–289, https://doi.org/10.1006/nimg.2001.0978 (2002).

Fan, L. et al. The Human Brainnetome Atlas: A New Brain Atlas Based on Connectional Architecture. Cerebral cortex 26, 3508–3526, https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhw157 (2016).

Wang, J. et al. GRETNA: a graph theoretical network analysis toolbox for imaging connectomics. Frontiers in human neuroscience 9, 386, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2015.00386 (2015).

Achard, S. & Bullmore, E. Efficiency and cost of economical brain functional networks. PLoS computational biology 3, e17, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.0030017 (2007).

Lei, D. et al. Connectome-Scale Assessments of Functional Connectivity in Children with Primary Monosymptomatic Nocturnal Enuresis. BioMed research international 2015, 463708, https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/463708 (2015).

Watts, D. J. & Strogatz, S. H. Collective dynamics of ‘small-world’ networks. Nature 393, 440–442, https://doi.org/10.1038/30918 (1998).

Latora, V. & Marchiori, M. Efficient behavior of small-world networks. Physical review letters 87, 198701, https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.87.198701 (2001).

Rubinov, M. & Sporns, O. Complex network measures of brain connectivity: uses and interpretations. NeuroImage 52, 1059–1069, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.10.003 (2010).

Lei, D. et al. Disrupted Functional Brain Connectome in Patients with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Radiology 276, 818–827, https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.15141700 (2015).

Zalesky, A., Fornito, A. & Bullmore, E. T. Network-based statistic: identifying differences in brain networks. NeuroImage 53, 1197–1207, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.06.041 (2010).

Xie, T. & He, Y. Mapping the Alzheimer’s brain with connectomics. Frontiers in psychiatry 2, 77, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2011.00077 (2011).

Oshiro, Y., Quevedo, A. S., McHaffie, J. G., Kraft, R. A. & Coghill, R. C. Brain mechanisms supporting discrimination of sensory features of pain: a new model. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 29, 14924–14931, https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5538-08.2009 (2009).

Oshiro, Y., Quevedo, A. S., McHaffie, J. G., Kraft, R. A. & Coghill, R. C. Brain mechanisms supporting spatial discrimination of pain. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 27, 3388–3394, https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5128-06.2007 (2007).

Burstein, R., Noseda, R. & Borsook, D. Migraine: multiple processes, complex pathophysiology. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience 35, 6619–6629, https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0373-15.2015 (2015).

Lobanov, O. V., Quevedo, A. S., Hadsel, M. S., Kraft, R. A. & Coghill, R. C. Frontoparietal mechanisms supporting attention to location and intensity of painful stimuli. Pain 154, 1758–1768, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2013.05.030 (2013).

Wiech, K., Ploner, M. & Tracey, I. Neurocognitive aspects of pain perception. Trends in cognitive sciences 12, 306–313, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2008.05.005 (2008).

Kim, J. H. et al. Thickening of the somatosensory cortex in migraine without aura. Cephalalgia: an international journal of headache 34, 1125–1133, https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102414531155 (2014).

Messina, R. et al. Cortical abnormalities in patients with migraine: a surface-based analysis. Radiology 268, 170–180, https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.13122004 (2013).

Aderjan, D., Stankewitz, A. & May, A. Neuronal mechanisms during repetitive trigemino-nociceptive stimulation in migraine patients. Pain 151, 97–103, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2010.06.024 (2010).

Afridi, S. K. et al. A PET study exploring the laterality of brainstem activation in migraine using glyceryl trinitrate. Brain: a journal of neurology 128, 932–939, https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awh416 (2005).

Moulton, E. A. et al. Painful heat reveals hyperexcitability of the temporal pole in interictal and ictal migraine States. Cerebral cortex 21, 435–448, https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhq109 (2011).

Afridi, S. K. et al. A positron emission tomographic study in spontaneous migraine. Archives of neurology 62, 1270–1275, https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.62.8.1270 (2005).

Goadsby, P. J. et al. Pathophysiology of Migraine: A Disorder of Sensory Processing. Physiological reviews 97, 553–622, https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00034.2015 (2017).

Schwedt, T. J. et al. Allodynia and descending pain modulation in migraine: a resting state functional connectivity analysis. Pain medicine 15, 154–165, https://doi.org/10.1111/pme.12267 (2014).

Apkarian, A. V., Hashmi, J. A. & Baliki, M. N. Pain and the brain: specificity and plasticity of the brain in clinical chronic pain. Pain 152, S49–64, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2010.11.010 (2011).

Vincent, M. et al. Enhanced interictal responsiveness of the migraineous visual cortex to incongruent bar stimulation: a functional MRI visual activation study. Cephalalgia: an international journal of headache 23, 860–868 (2003).

Tedeschi, G. et al. Increased interictal visual network connectivity in patients with migraine with aura. Cephalalgia: an international journal of headache 36, 139–147, https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102415584360 (2016).

Wang, M. et al. Visual cortex and cerebellum hyperactivation during negative emotion picture stimuli in migraine patients. Scientific reports 7, 41919, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep41919 (2017).

Nieuwenhuys, R. The insular cortex: a review. Progress in brain research 195, 123–163, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53860-4.00007-6 (2012).

Brooks, J. C. & Tracey, I. The insula: a multidimensional integration site for pain. Pain 128, 1–2, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2006.12.025 (2007).

Frot, M., Faillenot, I. & Mauguiere, F. Processing of nociceptive input from posterior to anterior insula in humans. Human brain mapping 35, 5486–5499, https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.22565 (2014).

Stankewitz, A. & May, A. Increased limbic and brainstem activity during migraine attacks following olfactory stimulation. Neurology 77, 476–482, https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e318227e4a8 (2011).

Stankewitz, A., Schulz, E. & May, A. Neuronal correlates of impaired habituation in response to repeated trigemino-nociceptive but not to olfactory input in migraineurs: an fMRI study. Cephalalgia: an international journal of headache 33, 256–265, https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102412470215 (2013).

Brooks, J. C., Nurmikko, T. J., Bimson, W. E., Singh, K. D. & Roberts, N. fMRI of thermal pain: effects of stimulus laterality and attention. NeuroImage 15, 293–301, https://doi.org/10.1006/nimg.2001.0974 (2002).

Symonds, L. L., Gordon, N. S., Bixby, J. C. & Mande, M. M. Right-lateralized pain processing in the human cortex: an FMRI study. Journal of neurophysiology 95, 3823–3830, https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.01162.2005 (2006).

Greicius, M. D., Supekar, K., Menon, V. & Dougherty, R. F. Resting-state functional connectivity reflects structural connectivity in the default mode network. Cerebral cortex 19, 72–78, https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhn059 (2009).

Bullmore, E. & Sporns, O. Complex brain networks: graph theoretical analysis of structural and functional systems. Nature reviews. Neuroscience 10, 186–198, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2575 (2009).

Hayasaka, S. & Laurienti, P. J. Comparison of characteristics between region-and voxel-based network analyses in resting-state fMRI data. NeuroImage 50, 499–508, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.051 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81571658 and 81201082 to X. X. Du), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81200941 to J. Su, 81271302 to J.R. Liu), project from Shanghai Jiao Tong University Medical Engineering Cross Research Foundation (No. YG2014MS07 to J. Su), research innovation project from Shanghai municipal science and technology commission (No. 14JC1404300, to J.R. Liu), the “prevention and control of chronic diseases project” of Shanghai Hospital Development Center (No. SHDC12015310, to J.R. Liu), project from SHSMU-ION Research Center for Brain Disorders (No. 2015NKX006, to J.R. Liu), project from Shanghai Municipal Education Commission—Gaofeng Clinical Medicine Grant Support (No. 20161422 to J.R. Liu), Clinical Research Project from Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (No. DLY201614 to J.R. Liu), and Biomedicine Key program from Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Commission (No. 16411953100 to J.R. Liu).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.D. and J.L. conceived and designed the study. J.Z. and X.D. designed the experiments and parameters, the statistical analyses and wrote the main manuscript text. J.Z., J.S., M.W., Y.Z., Q.Z., Q.Y., H.L., H.Z., G.L., Y.W., Y.L., F.L., M.Z., Y.S., T.H., R.Z., Y.Q. and J.L. performed the experiments. J.L. and X.D. reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J., Su, J., Wang, M. et al. The Posterior Insula Shows Disrupted Brain Functional Connectivity in Female Migraineurs Without Aura Based on Brainnetome Atlas. Sci Rep 7, 16868 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17069-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17069-8

This article is cited by

-

Aberrant dynamic functional network connectivity in vestibular migraine patients without peripheral vestibular lesion

European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology (2023)

-

Sex Differences in Chronic Migraine: Focusing on Clinical Features, Pathophysiology, and Treatments

Current Pain and Headache Reports (2022)

-

Differences in topological properties of functional brain networks between menstrually-related and non-menstrual migraine without aura

Brain Imaging and Behavior (2021)

-

Hyperconnection and hyperperfusion of overlapping brain regions in patients with menstrual-related migraine: a multimodal neuroimaging study

Neuroradiology (2021)

-

Altered structural brain network topology in chronic migraine

Brain Structure and Function (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.