Abstract

The honeybee is a model organism for studying learning and memory formation and its underlying molecular mechanisms. While DNA methylation is well studied in caste differentiation, its role in learning and memory is not clear in honeybees. Here, we analyzed genome-wide DNA methylation changes during olfactory learning and memory process in A. mellifera using whole genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) method. A total of 853 significantly differentially methylated regions (DMRs) and 963 differentially methylated genes (DMGs) were identified. We discovered that 440 DMRs of 648 genes were hypermethylated and 274 DMRs of 336 genes were hypomethylated in trained group compared to untrained group. Of these DMGs, many are critical genes involved in learning and memory, such as Creb, GABA B R and Ip3k, indicating extensive involvement of DNA methylation in honeybee olfactory learning and memory process. Furthermore, key enzymes for histone methylation, RNA editing and miRNA processing also showed methylation changes during this process, implying that DNA methylation can affect learning and memory of honeybees by regulating other epigenetic modification processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Honeybees (Apis mellifera) are social insects with important economic and ecological value due to their pollination services. They are able to distinguish different colors1, odors2, even the relationship between objects, such as, sequential order3, and the upper and lower4. Even more astonishing is their ability to learn abstract rules and concepts5,6. Due to their remarkable abilities in learning and memory and the relative simple structure of their brains, honeybees are considered a good model for neurobiology. But the molecular mechanisms underlying the learning and memory process of honeybees are not well understood.

Epigenetic modifications, such as DNA methylation7,8, histone modifications9,10, and miRNA processing11,12, have been shown to be involved in learning and memory processes in vertebrates. DNA methylation plays a critical role in long-term memory formation in many organisms and different learning paradigms8. The change of DNA methylation levels, which is regulated mainly by the activity of DNA methyltransferase (DNMTs), directly regulates the expression level of genes involved in memory formation in the brain13,14.

The honeybee genome possesses a complete, functional DNA methylation system, which includes an ortholog of Dnmt3 and two orthologs of Dnmt1 (AmDnmt1a and AmDnmt1b)15. Moreover, all these three DNMTs have catalytic activity. DNA methylation is regarded as the main mechanism regulating queen-worker caste differentiation in honeybees, and many studies have surveyed DNA methylation differences between these two castes16,17,18,19,20. DNA methylation is also reported to be closely associated with learning and memory processes in honeybees21,22,23. Inhibiting the activity of DNMT in honeybees using zebularine revealed that DNA methylation mediates long-term memory formation in honeybees after associative learning, but not short-term memory formation21,22. By measuring the methylation of 30 memory associated genes in honeybees, Biergans et al.23 found that, during memory formation process, memory associated genes are regulated by a temporally complex epigenetic mechanism.

Even though it is known DNA methylation is involved in long-term memory formation in A. mellifera, the actual pattern of DNA methylation after learning and memory has not been studied in honeybees. In this process, how many genes are methylated? To what extent does DNA methylation affect gene expression? Here, we analyzed the genome-wide DNA methylation changes following olfactory learning and memory in A. mellifera through WGBS method, and identified many DMRs and associated genes. Our results suggest extensive involvement of DNA methylation in honeybee olfactory learning and memory.

Results

DNA methylation patterns

After sequencing, about 72,434,814 and 76,497,724 raw reads with a Q20 value of more than 92% were generated for the two samples, respectively (Table 1). After removing low-quality reads, 58,669,954 (7.34 Gb) and 64,500,902 (8.06 Gb) clean reads which were more than 25 × coverage of the 285 Mb A. mellifera reference genome remained, and were mapped to the genome. Finally, 56.95% and 61.10% of the reads were uniquely mapped to the honeybee genome and more than 77% of the total clean reads have a coverage of >5 × on the genome (Table 1). The BS conversion rates are more than 99.83% in each sample, indicating high T-C conversion during bisulfite treatment.

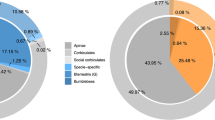

A total of 139,430 and 140,997 methylated cytosines (mCs) were detected in trained and untrained groups, both occupying about 0.19% of all the cytosine sites in the honeybee genome (Table 2). Of these mCs, the percentages of mCs in CG, CHG (H represents A, C or T) and CHH contexts in the trained group were 99.47%, 0.06%, 0.47% (Fig. 1A), occupying 0.6829%, 0.0010%, 0.0014% of the genome-wide CG, CHG and CHH sites respectively (Table 2); the corresponding numbers in the untrained group were 99.50%, 0.06%, 0.44% (Fig. 1B), occupying 0.6908%, 0.0010%, 0.0014% of the genome-wide CG, CHG and CHH sites respectively (Table 2).

Sequence preferences flanking the methylated C sites

We analyzed the relationship between sequence context and methylation preference. The same criteria used by Lister et al.24 were adopted to define the methylation level. That is, for CG context, C sites with methylation level exceeding 75% were defined as high methylation sites, and C sites with methylation level lower than 75% were defined as low methylation sites; while for non-CG context, C sites with methylation level exceeding or under 25% are defined as high or low methylation sites, respectively. The sequence characteristics of 9-mer sequences around the methylated C sites under different context sequence were analyzed (Fig. 2). In the CG contexts of both high and low methylation regions, it showed no significant difference between the trained and untrained groups in the sequence enrichment based on the genomic regions, and “-TACGTA-A” and “ATTCGAAA(T)A” were the most preferred sequences around the methylated C sites in these two type of regions. While in the non-CG context the methylation showed an obvious sequence context preference, especially in the low methylation regions, in which “CATCAGCAT” and “TATCAGACT”, “TTTCTTTTT” and “TTTCATTTTT” are the most preferred sequences for the trained and untrained groups in CHG context and CHH context respectively. In the high methylation regions, the largest difference between the trained and untrained groups both in CHG and CHH context was the 3rd base of the 9-mer sequences which was closely adjacent to the methylated C site. These results suggest that methylation in non-CG sites changed greatly with a sequence preference mode during olfactory learning process in honeybees.

DNA methylation level in different genome components

The DNA methylation level in general showed diverse distributions in different functional genomic regions. Thus, we investigated the DNA methylation level in five different genome components including promoter, 5′UTR, exon, intron and 3′UTR, using sliding window analysis. As shown in Fig. 3, the trained group and the untrained group showed similar pattern of methylation level distribution. In the CG context, the promoter region in which the methylation level was gradually decreased along the promoter overall showed the highest methylation level compared to other genome components, followed by the exon region, and the next was the 3′UTR; the 5′UTR and intron regions exhibited a very low level of methylation. In the CHG and CHH context, the distributions of methylation level were irregular in both trained and untrained groups.

Differentially methylated regions and related genes

Differentially methylated regions between the trained and untrained groups were identified using swDMR software with rigorous parameters. A total of 853 DMRs throughout the whole genome were identified (Table S2). In order to explore the relationship between DNA methylation and gene transcription, we annotated all these DMRs using the genomic location of each DMR and the annotation information of the genome structure of A. mellifera. As a result, 714 DMRs belonging to 963 genes were annotated (Table S3). Of these, 440 DMRs corresponding to 648 genes were hypermethylated and 274 DMRs corresponding to 336 genes were hypomethylated in trained group compared to untrained group. These DMRs were mainly distributed in introns and exons with a percentage of 30.42% and 32.63% respectively (Fig. 4A), moreover, in all the five functional components the number of hypermethylated DMRs were larger than that of hypomethylated (Fig. 4B). Boxplot analysis of DMRs indicated that the methylation level of the trained group was higher than that of the untrained group (Fig. 5).

The distribution of DMRs in different genomic components. (A) Percentage of DMRs in different genomic components. (B) The number of hypermethylated and hypomethylated DMRs in different genomic components. Many DMRs were counted into more than two components because these DMRs cover multiple genomic components.

We paid more attention to those genes already reported to be involved in learning and memory and found many such genes from the DMG list, including cAMP response element-binding (Creb), metabotropic GABA-B receptor (GABA B R), and inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate kinase (Ip3k), and so on.

GO and KEGG analysis of DMGs

GO and KEGG pathway analysis were performed to analyze the significant function and pathways of the DMGs. All the DMGs were mapped to terms in the GO database and compared with the whole genome background. For all the DMGs, just the GO term “binding” with 569 DMGs in the categories of the molecular function was significantly enriched (corrected p value < 0.05), implying that a wide range of genes experienced transcriptional regulation during the process of learning and memory (Table S4). For the hypomethylated genes, 151 GO terms was significantly enriched (corrected p value < 0.05), whilst no term showed significant enrichment for the hypermethylated genes. In the KEGG analysis, no pathway was significantly enriched (corrected p value < 0.05).

Association analysis between the DMGs and the differentially expressed genes (DEGs)

To explore the relationship between these DMGs and the DEGs found at the transcriptome level, we compared DMGs with the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) reported in our previous research25. In that study, we identified 259 DEGs associated with the process of honeybee olfactory learning and memory by digital gene expression analysis. As a result, we found 30 overlapped genes corresponding to 37 DMRs (Fig. 6, Table S5), including two important learning and memory related genes: Tomosyn and synaptojanin 1. Of the 37 DMRs, 20 were hypermethylated and 17 hypomethylated. Usually, hypermethylation cause down-regulation of gene transcription, we analyzed the methylation state of the DMRs within the DEGs, and found that 16 DMGs containing hypermethylated regions are down-regulated expression after olfactory learning.

Discussion

DNA methylation tends to represses transcription of olfactory learning and memory related genes

To analyze the effect of olfactory learning and memory on DNA methylation, we surveyed the genome-wide DNA methylation changes during this process using WGBS method. Many differentially methylated regions and associated genes were identified. Of the 714 DMRs of 963 genes, more DMRs were hypermethylated after training. Specifically, 167 of the 261 DMRs covering promoter region were hypermethylated (Fig. 4B), suggesting that transcription of most DMGs might be down-regulated during this process since DNA methylation usually represses gene transcription26,27,28,29, especially methylation in the promoter26,27,28 and the first exon regions26,29, which is in accordance with our previous observations25,30 as well as the results from another research group31 that most differentially expressed genes are down-regulated after olfactory learning and memory training. Our results suggest that DNA methylation tends to repress gene transcription after olfactory learning and memory in honeybees, although we just found 16 down-regulated hypermethylation-region containing genes in the DMGs and DEGs comparison analysis. The main reason for this relatively low number might be that the number of DEGs detected in our previous study was relatively small since there were just 259 DEGs.

Key genes involved in learning and memory pathways

The learning and memory process contains three main signal transduction pathways, including cAMP-PKA, Ca2+-CaMK IV and MAPK pathways32. We analyzed key genes in these three signal pathways and found several such genes from the 963 DMGs, which were Creb (XM_623343.3), GABA B R (XM_394454.2) and Ip3k (NM_001014992.1). DMRs related to all these genes were hypermethylated after training.

Creb is an evolutionarily highly conserved gene critical in learning and memory process in a wide range of animals and is the central collection point downstream of the cAMP-PKA, Ca2+-CaMK IV and MAPK signal transduction pathways32. In mammalian, CREB generally functions as a positive regulator in memory formation through activating the expression of its downstream genes33,34, and several genes, including C-fos, Arc and Bdnf, are reported to be its targets35,36,37. In Drosophila, however, Creb produces multiple isoforms by alternative splicing, and two of the isoforms, dCREB2-a and dCREB2-b, are functional antagonist, acting as activator and repressor respectively in long-term memory formation38,39,40. Like that in Drosophila, the honeybee Creb also has multiple alternative splicing isoforms which can be known from the mRNA sequences deposited in GenBank database. We found that the Creb related DMR in our study was hypermethylated after learning and memory and was located in the intron region. It is possible that this hypermethylated DMR regulates alternative splicing of A. mellifera Creb gene because there are evidence that DNA methylation in introns can modulate alternative splicing41,42, but further experiments are needed to verify this.

The metabotropic GABA-B receptor is the mediator of the inhibitory effects of the GABA which is the main inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain43. By binding to GABA, GABABR can mediate slow and sustained inhibitory responses through downstream Ca2+/K+ channels43. The hypermethylation of GABA B R related DMR after learning and memory training might cause down-regulation of GABA B R during learning and memory process. Ip3k is the common downstream target of Pka, Pkc and CamkII, which are important genes in the learning and memory signal transduction pathways44. PKA and CaMKII are positive regulators of Ip3k 45,46, and PKC is a negative regulator47. Research showed that IP3K-A plays a critical role in the spatial memory48.We found that Ip3k related DMR was hypomethylated, which might cause up-regulation of Ip3k expression, suggesting that IP3K might be a positive regulator during the learning and memory process.

Other genes involved in learning and memory process

In addition to the above mentioned critical genes, from the DMGs we also found several other genes reported to be involved in learning and memory process, they were synaptojanin 1 (XM_395173.4), syntaxin 1 A (XM_393760.4), syntaxin-binding protein (Tomosyn, XM_391820.4), synaptosomal-associated protein (Snap-25, XM_394588.4), glutamate-gated chloride channel (GluCl, NM_001077809.1), and cGMP-dependent protein kinase foraging gene (For, NM_001011581.1). Of them, DMR related to synaptojanin 1 and one of the two DMRs related to GluCl were hypermethylated, while DMRs related to other genes were hypomethylated.

Synaptojanin 1 is a phosphoinositide phosphatase acting as a key negative regulator controlling the levels of the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate in the nervous tissue49. Down-regulating the expression of synaptojanin 1 in mice through transgenic method reduces cognitive deficits of mice50. Synaptojanin 1 related DMR was hypermethylated in this study and its expression was down-regulated after learning and memory in our previous study, implying that DNA methylation might has repressed its expression which will further promote the synthesis of the phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate. These results are consistent with its role as a negative regulator of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate.

Syntaxin 1 A is an integral membrane protein playing a crucial role in neurotransmitter release by interacting with synaptobrevin (VAMP) and SNAP-2551. Knocking out syntaxin 1 A in mice leads to impairment of its consolidation and extinction of conditioned fear memory as well as the long-term potentiation in the hippocampal slice52, suggesting that syntaxin 1 A acts as a positive regulator in learning and memory. SNAP-25 is a 25 kDa protein involved in regulating synaptic vesicle exocytosis and voltage-gated calcium channels activity53. Experiments in mice indicated that SNAP-25s distributed in different region of hippocampal have different biological functions in learning and memory54,55. For encodes a cyclic guanosine-3,5-monophosphate (cGMP)-dependent protein kinase (PKG). It has been widely reported to play a role in food-search behavior of Drosophila 56. But studies in Drosophila showed that it is also required for visual learning57,58. In our study, one DMR related to syntaxin 1 A, three DMRs related to Snap-25 with two of them lying in promoter region, and two DMRs related to For were identified, and all of them were hypomethylated, implying that the transcription of these three genes might be activated through hypomethylation and act as positive regulators in learning and memory process.

Tomosyn and GluCl both play an inhibitory role in synaptic transmission. Tomosyn is involved in inhibiting vesicle priming and synaptic transmission59, and plays a role in odor memory and spatial learning and memory60,61. GluCl gene was reported to be involved in inhibitory transmission in olfactory learning and memory in the honeybees62. Moreover, through alternative splicing it produces two subunits to differentially regulate the olfactory memory processes of the honeybee63. We found that two DMRs related to Tomosyn and one DMR located in the promoter region of GluCl were hypomethylated, which might promote transcription of these two genes.

Key genes involved in epigenetic modification

Other epigenetic mechanisms, such as histone methylation, RNA editing and miRNA, also have an effect on learning and memory process. We found that the euchromatin histone methyltransferase 1 (EHMT1, XM_003249151.1), adenosine deaminases (ADARs, XM_394309.4) and Dicer1 (NM_001123013.1), which are key enzymes for histone methylation, RNA editing and miRNA processing, respectively, were highly methylated after training.

EHMT1 is a highly conserved protein which catalyzes mono- and dimethylation of histone 3 at lysine 9 (H3K9me2) in euchromatic DNA by interacting with EHMT264. It plays an important role in human cognition65 and mice memory66. The differential methylation of Ehmt1 after learning and memory suggests that DNA methylation can regulate learning and memory by modulating the histone methylation process. Adenosine deaminases are double-strand RNA-binding proteins involved in adenosine to inosine (A to I) RNA editing. Studies in Caenorhabditis elegans, Drosophila and mouse indicated that ADAR mediated RNA editing is crucial for cognitive and behavioral correlates of nervous system function67. The promoter region of honeybee Adar gene was highly methylated after learning and memory, which might repress its transcription and reduce A- I RNA editing. Dicer1 is a type III RNAse responsible for the processing of microRNA precursors into mature miRNAs as well as long dsRNA substrates into small interfering RNAs (siRNAs)68,69,70. Mutation of Dicer1 can enhance memory strength of mice71, suggesting that Dicer1 acts as an inhibitor in learning and memory process of mice. The hypermethylation of Dicer1 after learning and memory in our study suggests that down-regulated expression of Dicer1 promotes the learning and memory in honeybee. In a word, the DNA methylation changes of these critical genes of different epigenetic regulation implying that DNA methylation might regulate the learning and memory process through regulating other epigenetic modification process.

Materials and Methods

Experimental bees

The A. mellifera colonies used in this experiment were kept in Honeybee Research Institute, Jiangxi Agricultural University, China. The experimental bees were from a colony headed by a queen artificially inseminated with semen from a single drone to ensure a highly similar genetic background. Frames containing near emerging pupae were enclosed inside nylon-net bags and kept inside the colony overnight. The next morning the newly emerged worker bees (<12 h after emergence) were gathered into rectangular boxes and then maintained in an incubator at a constant temperature of 34 °C in a light-dark cycle of 12 h light and 12 h dark. The bees were fed daily with a mixture of 1 M sucrose and bee-bread for one week before the experiment.

PER experiment

The proboscis extension reflex (PER) experiment began in the morning of the 8 day old bees (the day of emergence = 1 day old). The experiment procedures followed that of Letzkus72 and one of our previous studies25. Briefly, the bees were trained by a positive stimulus and a negative stimulus. The lemon odor plus 1 M sucrose solution were used as positive stimulus (reward) and vanilla odor plus saturated saline were used as negative stimulus (punishment). Twenty-four hours after training, retention tests were carried out. At this time, the bees were first given the negative stimulus, then, the positive stimulus. The bees were given three trails, those bees giving a correct response to the positive stimulus in at least two of the three trials (a very few bees didn’t extend their proboscis actively at the third trial because they ate a little more sucrose solution during the first two trials) and not giving a response to the negative stimulus in all the three trials were considered as having learned the two stimuli and good memory performers. 30 min after completion of the tests, the heads of the trained bees that have a good performance in tests and those of untrained bees (control group) were sampled and stored in liquid nitrogen. In order to get enough honeybee brain samples, six biological replicates of PER experiment were performed. For each biological replicate, the same number of learned bees and untrained bees were sampled (Table S1).

Brain dissection

The brains were dissected from the sampled heads of honeybees under a stereo microscope using a sharp razor blade in normal saline (137 mmol/L NaCl, 2.7 mmol/L KCl, 10 mmol/L Na2HPO4, 2 mmol/L KH2PO4). The dissected brains were collected into a 1.5 ml RNase- and DNase-free Eppendorf tube placed on dry ice. Then, the sampled brain tissues were stored at −80 °C until use.

Genomic DNA extraction

The genomic DNA was isolated from the dissected honeybee brain samples that contain brain tissues from about 50 worker bees using DNeasy Blood & Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to its protocol. Genomic DNA degradation and contamination were checked by agarose gel electrophoresis analysis. DNA purity (ratio of OD260/280) was detected using the NanoPhotometer® spectrophotometer (IMPLEN, CA, USA) and DNA concentration was measured using Qubit® DNA Assay Kit in Qubit® 2.0 Flurometer (Life Technologies, CA, USA).

Library preparation and quantification

Sequencing libraries were constructed for the trained and untrained groups using the above isolated genomic DNAs. For each library, a total amount of 5.2 µg genomic DNA added with 26 ng lambda DNA as negative control were randomly fragmented to 200–300 bp by sonication with Covaris S220 (Covaris, MA, USA). After purification, the DNA fragments were end repaired and were added an adenine to its two 3′ terminals. Then, cytosine-methylated sequencing adaptors were ligated to the two terminals of the DNA fragments according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After that, these DNA fragments were treated twice with bisulfite using EZ DNA Methylation-GoldTM Kit (Zymo Research), followed by PCR amplification. Library concentration was quantified by Qubit® 2.0 Flurometer (Life Technologies, CA, USA) and quantitative PCR, and the length of the inserted fragments was detect using an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system. Finally, the libraries were subjected to125 bp paired-end sequencing using the Illumina HiSeq. 2500 platform.

The original image data were transformed into raw sequences (Sequenced Reads) by Base Calling, and stored in FASTQ files. The distribution of sequencing error rate and bases content along reads were analyzed through in-house Perl scripts. The raw reads in FastQ format were processed using the Trimmomatic software73 as follows: (1) removing adaptors; (2) removing reads containing N (unknown base) more than 10% and; (3) removing the low quality reads (the percentage of the low quality bases (Phred score ≤20) ≥50%). Meanwhile, Q20, Q30 and GC content of the data were calculated using in-house scripts. The clean reads were submitted to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive database with accession number SRR5295651 for trained group and SRR5312519 for untrained group.

Reads mapping to the reference genome

After removing the low quality reads, all the bisulfite-treated reads were aligned to the A. mellifera genome sequences v4.5 downloaded from NCBI (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/genomes/Apis_mellifera) using Bismark software version 0.12.574 with the default parameters. Before mapping, both the A. mellifera genome sequences and the clean reads were transformed into bisulfite-converted version (C-to-T and G-to-A converted) and the converted genome sequences were indexed using Bowtie2 software75.

Those clean reads that produce a unique best alignment from the two alignment processes (original top and bottom strand) were compared to the normal honeybee genome sequence. Then, methylation state of all cytosine positions in the reads were inferred according to the alignment results. Those identical reads that aligned to the same regions of the honeybee genome were regarded as duplicated ones. The sequencing depth and coverage of each sample were summarized using deduplicated reads. The results of methylation extractor were transformed into bigWig format for visualization using IGV browser. Sodium bisulfite non-conversion rate was calculated as the percentage of cytosines sequenced at cytosine reference positions in the lambda genome.

Estimating methylation level

To identify the methylation site, we modeled the sum of methylated counts as a binomial (Bin) random variable with methylation rate.

A sliding-window approach was used to calculate the number of methylated and unmethylated reads with window size 3,000 bp and step size 600 bp76. Methylation level (ML) for each identified C site was calculated by the following formula:

Here reads (mC) represents number of reads containing a methylated C in this C site. Reads (umC) represents number of reads containing an unmethylated C in this C site. The ML value was further corrected with the bisulfite non-conversion rate according to previous studies77.

Differentially methylated regions analysis

Differentially methylated regions (DMRs) were identified based on the methylation imformation of each site using the swDMR software developed by Wang et al.78 and the corresponding procedures. At first, a sliding-window approach with window size of 1000 bp and step length of 100 bp were adopted to scan the genome of the trained and untrained groups. Only windows containing more than 10 cytosine sites were retained for calculating the mean methylation level. Those windows that have fold change and difference of mean methylation level higher than 2 and 0.1 between the two samples and P value < 0.05 in the Fisher’s Exact Test were considered as potential DMRs. Repeating the above operations until all the potential DMRs genome-wide were identified, and their P values were corrected using FDR method (corrected p-value < 0.05). After that, the overlapping potential DMRs were subjected to merging and statistical test again and again, the final merged regions were regarded as candidate DMRs.

DMRs were annotated using the gene annotation file of A. mellifera reference genome v4.5 downloaded from NCBI (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/genomes/Apis_mellifera/GFF) by comparing the chromosome position information of DMRs with the corresponding annotation information in the gene annotation file. When a DMR overlapped with a gene or a functional component of a gene, including promoter, 5′UTR, exon, intron and 3′UTR, it was assigned to this gene and its components. The position information of the 5′UTR, exon, intron and 3′UTR of each gene can be obtained from the gene annotation file. The promoter region contains 2 kb region upstream the transcription start site (TSS).

GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of DMGs

Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of DMGs was performed using the GOseq R package79. GO terms with corrected p-value < 0.05 were considered significantly enriched by DMGs.

The KEGG pathway enrichment analysis identified significantly enriched metabolic pathways or signal transduction pathways in the DMGs by comparing with the whole-genome background.

Data availability

The RNA-Seq data of trained group and untrained group can be obtained from the following links.

Trained group:

ftp://ftp-trace.ncbi.nih.gov/sra/sra-instant/reads/ByRun/sra/SRR/SRR529/SRR5295651/:

Untrained group:

ftp://ftp-trace.ncbi.nih.gov/sra/sra-instant/reads/ByRun/sra/SRR/SRR531/SRR5312519/).

References

von Frisch, K. Der Farbensinn und Formensinn der Biene. Fischer, Jena (1914).

Menzel, R., Hammer, M., Müller, U. & Rosenboom, H. Behavioral, neural and cellular components underlying olfactory learning in the honeybee. J. Physiol. Paris 90, 395–398 (1996).

Zhang, S., Bock, F., Si, A., Tautz, J. & Srinivasan, M. Visual working memory in decision making by honey bees. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 5250 (2005).

Avargues-Weber, A., Dyer, A. G. & Giurfa, M. Conceptualization of above and below relationships by an insect. Proc. R. Soc. London Ser. B 278, 898–905 (2011).

Giurfa, M., Zhang, S., Jenett, A., Menzel, R. & Srinivasan, M. V. The concepts of ‘sameness’ and ‘difference’ in an insect. Nature 410, 930–932 (2001).

Avarguès-Weber, A., Dyer, A. G., Combe, M. & Giurfa, M. Simultaneous mastering of two abstract concepts by the miniature brain of bees. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 7481–7486 (2012).

Yu, N. K., Baek, S. H. & Kaang, B. K. DNA methylation-mediated control of learning and memory. Mol. Brain 4, 5 (2011).

Morris, M. J. & Monteggia, L. M. Role of DNA methylation and the DNA methyltransferases in learning and memory. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 16, 359–371 (2014).

Gupta, S. et al. Histone methylation regulates memory formation. J. Neurosci. 30, 3589–3599 (2010).

Miller, C. A., Campbell, S. L. & Sweatt, J. D. DNA methylation and histone acetylation work in concert to regulate memory formation and synaptic plasticity. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 89, 599–603 (2008).

Busto, G. U., Guven-Ozkan, T. & Davis, R. L. MicroRNA function in Drosophila memory formation. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 43, 15–24 (2016).

Konopka, W., Schütz, G. & Kaczmarek, L. The microRNA contribution to learning and memory. Neuroscientist 17, 468–474 (2011).

Miller, C. A. & Sweatt, J. D. Covalent modification of DNA regulates memory formation. Neuron 53, 857–869 (2007).

Miller, C. A. et al. Cortical DNA methylation maintains remote memory. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 664–666 (2010).

Wang, Y. et al. Functional CpG methylation system in a social insect. Science 314, 645–647 (2006).

Kucharski, R., Maleszka, J., Foret, S. & Maleszka, R. Nutritional control of reproductive status in honeybees via DNA methylation. Science 319, 1827–1830 (2008).

Lyko, F. et al. The honey bee epigenomes: differential methylation of brain DNA in queens and workers. PLoS Biol. 8, e1000506 (2010).

Shi, Y. Y. et al. Diet and cell size both affect queen-worker differentiation through DNA methylation in honey bees (Apis mellifera, Apidae). PLoS One 6, e18808 (2011).

Foret, S. et al. DNA methylation dynamics, metabolic fluxes, gene splicing, and alternative phenotypes in honey bees. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 4968–4973 (2012).

Shi, Y. Y. et al. Genomewide analysis indicates that queen larvae have lower methylation levels in the honey bee (Apis mellifera). Naturwissenschaften 100, 193–197 (2013).

Lockett, G. A., Helliwell, P. & Maleszka, R. Involvement of DNA methylation in memory processing in the honey bee. Neuroreport 21, 812–816 (2010).

Biergans, S. D., Jones, J. C., Treiber, N., Galizia, C. G. & Szyszka, P. DNA methylation mediates the discriminatory power of associative long-term memory in honeybees. PLoS One 7, e39349 (2012).

Biergans, S. D., Giovanni Galizia, C., Reinhard, J. & Claudianos, C. Dnmts and Tet target memory-associated genes after appetitive olfactory training in honey bees. Sci. Rep. 5, 16223 (2015).

Lister, R. et al. Human DNA methylomes at base resolution show widespread epigenomic differences. Nature 462, 315–322 (2009).

Wang, Z. L., Wang, H., Qin, Q. H. & Zeng, Z. J. Gene expression analysis following olfactory learning in Apis mellifera. Mol. Biol. Rep. 40, 1631–1639 (2013).

Lou, S. et al. Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing of multiple individuals reveals complementary roles of promoter and gene body methylation in transcriptional regulation. Genome Biol. 15, 408 (2014).

Plass, C. & Soloway, P. D. DNA methylation, imprinting and cancer. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 10, 6–16 (2002).

Klose, R. J. & Bird, A. P. Genomic DNA methylation: the mark and its mediators. Trends Biochem. Sci. 31, 89–97 (2006).

Brenet, F. et al. DNA methylation of the first exon is tightly linked to transcriptional silencing. PLoS One 6, e14524 (2011).

Qin, Q. H. et al. The integrative analysis of microRNA and mRNA expression in Apis mellifera following maze-based visual pattern learning. Insect Sci. 21, 619–636 (2014).

Cristino, A. S. et al. Neuroligin-associated microRNA-932 targets actin and regulates memory in the honeybee. Nat. Commun. 5, 5529 (2014).

Johnston, M. V., Alemi, L. & Harum, K. H. Learning, memory, and transcription factors. Pediatr. Res. 53, 369–374 (2003).

Kida, S. A Functional Role for CREB as a Positive Regulator of Memory Formation and LTP. Exp. Neurobiol. 21, 136–140 (2012).

Kida, S. & Serita, T. Functional roles of CREB as a positive regulator in the formation and enhancement of memory. Brain Res. Bull. 105, 17–24 (2014).

Sheng, M., Thompson, M. A. & Greenberg, M. E. CREB: a Ca(2+)-regulated transcription factor phosphorylated by calmodulin-dependent kinases. Science 252, 1427–1430 (1991).

Kawashima, T. et al. Synaptic activity-responsive element in the Arc/Arg3.1 promoter essential for synapse-to-nucleus signaling in activated neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 316–321 (2009).

Finkbeiner, S. et al. CREB: a major mediator of neuronal neurotrophin responses. Neuron 19, 1031–1047 (1997).

Yin, J. C. et al. A Drosophila CREB/CREM homolog encodes multiple isoforms, including a cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase-responsive transcriptional activator and antagonist. Mol. Cell Biol. 15, 5123–5130 (1995).

Yin, J. C. et al. Induction of a dominant negative CREB transgene specifically blocks long-term memory in Drosophila. Cell 79, 49–58 (1994).

Yin, J. C., Del Vecchio, M., Zhou, H. & Tully, T. CREB as a memory modulator: induced expression of a dCREB2 activator isoform enhances long-term memory in Drosophila. Cell 81, 107–115 (1995).

Maunakea, A. K. et al. Conserved role of intragenic DNA methylation in regulating alternative promoters. Nature 466, 253–257 (2010).

Shukla, S. et al. CTCF-promoted RNA polymerase II pausing links DNA methylation to splicing. Nature 479, 74–79 (2011).

Han, H. A., Cortez, M. A. & Snead, O. C., III. GABAB Receptor and Absence Epilepsy in Jasper’s Basic Mechanisms of the Epilepsies [Internet]. (ed. Noebels, J. L., Avoli, M., Rogawski, M. A., Olsen, R. W., Delgado-Escueta, A.V.) (NCBI, 2012).

Xia, H. J. & Yang, G. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate 3-kinases: functions and regulations. Cell Res. 15, 83–91 (2005).

Sim, S. S., Kim, J. W. & Rhee, S. G. Regulation of D-myo-inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate 3-kinase by cAMP-dependent protein kinase and protein kinase C. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 10367–10372 (1990).

Communi, D., Vanweyenberg, V. & Erneux, C. D-myo-inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate 3-kinase A is activated by receptor activation through a calcium: calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II phosphorylation mechanism. EMBO J. 16, 1943–1952 (1997).

Lin, A. N., Barnes, S. & Wallace, R. W. Phosphorylation by protein kinase C inactivates an inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate 3-kinase purified from human platelets. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 170, 1371–1376 (1990).

Kim, I. H. et al. Spatial learning enhances the expression of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate 3-kinase A in the hippocampal formation of rat. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 124, 12–19 (2004).

Cremona, O. et al. Essential role of phosphoinositide metabolism in synaptic vesicle recycling. Cell 99, 179–188 (1999).

Zhu, L. et al. Reduction of synaptojanin 1 accelerates Aβ clearance and attenuates cognitive deterioration in an Alzheimer mouse model. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 32050–32063 (2013).

Sudhof, T. C. The synaptic vesicle cycle. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 27, 509–547 (2004).

Fujiwara, T. et al. Analysis of knock-out mice to determine the role of HPC-1/syntaxin 1A in expressing synaptic plasticity. J. Neurosci. 26, 5767–5776 (2006).

Jahn, R. & Scheller, R. H. SNAREs–engines for membrane fusion. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 631–643 (2006).

Hou, Q. et al. SNAP-25 in hippocampal CA1 region is involved in memory consolidation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 20, 1593–1603 (2004).

Hou, Q. L. et al. SNAP-25 in hippocampal CA3 region is required for long-term memory formation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 347, 955–962 (2006).

Sokolowski, M. B. Drosophila: genetics meets behaviour. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2, 879–890 (2001).

Wang, Z. et al. Visual pattern memory requires foraging function in the central complex of Drosophila. Learn. Mem. 15, 133–142 (2008).

Kuntz, S., Poeck, B., Sokolowski, M. B. & Strauss, R. The visual orientation memory of Drosophila requires Foraging (PKG) upstream of Ignorant (RSK2) in ring neurons of the central complex. Learn. Mem. 19, 337–340 (2012).

Gracheva, E. O. et al. Tomosyn inhibits synaptic vesicle priming in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Biol. 4, e261 (2006).

Chen, K., Richlitzki, A., Featherstone, D. E., Schwärzel, M. & Richmond, J. E. Tomosyn-dependent regulation of synaptic transmission is required for a late phase of associative odor memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 18482–18487 (2011).

Barak, B. et al. Neuron-specific expression of tomosyn1 in the mouse hippocampal dentate gyrus impairs spatial learning and memory. Neuromolecular Med. 15, 351–363 (2013).

El Hassani, A. K., Giurfa, M., Gauthier, M. & Armengaud, C. Inhibitory neurotransmission and olfactory memory in honeybees. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 90, 589–595 (2008).

Démares, F. et al. Differential involvement of glutamate-gated chloride channel splice variants in the olfactory memory processes of the honeybee Apis mellifera. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 124, 137–144 (2014).

Tachibana, M. et al. Histone methyltransferases G9a and GLP form heteromeric complexes and are both crucial for methylation of euchromatin at H3-K9. Genes Dev. 19, 815–826 (2005).

Kleefstra, T. et al. Loss-of-function mutations in euchromatin histone methyl transferase 1 (EHMT1) cause the 9q34 subtelomeric deletion syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 79, 370–377 (2006).

Balemans, M. C. et al. Hippocampal dysfunction in the Euchromatin histone methyltransferase 1 heterozygous knockout mouse model for Kleefstra syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22, 852–866 (2013).

Valente, L. & Nishikura, K. ADAR gene family and A-to-I RNA editing: diverse roles in posttranscriptional gene regulation. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 79, 299–338 (2005).

Hutvágner, G. et al. A cellular function for the RNA-interference enzyme Dicer in the maturation of the let-7 small temporal RNA. Science 293, 834–838 (2001).

Ketting, R. F. et al. Dicer functions in RNA interference and in synthesis of small RNA involved in developmental timing in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 15, 2654–2659 (2001).

Knight, S. W. & Bass, B. L. A role for the RNase III enzyme DCR-1 in RNA interference and germ line development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 293, 2269–2271 (2001).

Konopka, W. et al. MicroRNA loss enhances learning and memory in mice. J. Neurosci. 30, 14835–14842 (2010).

Letzkus, P. et al. Lateralization of olfaction in the honeybee Apis mellifera. Curr. Biol. 16, 1471–1476 (2006).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Krueger, F. & Andrews, S. R. Bismark: a flexible aligner and methylation caller for Bisulfite-Seq applications. Bioinformatics 27, 1571–1572 (2011).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

Smallwood, S. A. et al. Single-cell genome-wide bisulfite sequencing for assessing epigenetic heterogeneity. Nat. Methods 11, 817–820 (2014).

Lister, R. et al. Global epigenomic reconfiguration during mammalian brain development. Science 341, 1237905 (2013).

Wang, Z. et al. swDMR: a sliding window approach to identify differentially methylated regions based on whole genome bisulfite sequencing. PLoS One 10, e0132866 (2015).

Young, M. D., Wakefield, M. J., Smyth, G. K. & Oshlack, A. Gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq: accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 11, R14 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (No. 20123603120005), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31402147) and the Earmarked Fund for China Agriculture Research System (No. CARS-45-KXJ12).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.L.W. conceived the project and designed the experiments, Y.L., L.Z.Z., Y.Y., W.W.H. and Y.H.G. performed the experiments, Z.J.Z. provided help for sample collection, Z.L.W. and Y.L. analyzed RNA-Seq data, Z.L.W., Y.L. and Z.Y.H. wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Zhang, LZ., Yi, Y. et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation changes associated with olfactory learning and memory in Apis mellifera . Sci Rep 7, 17017 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17046-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17046-1

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.