Abstract

Extracellular vesicles (EVs), such as exosomes, have been identified as regulators of vascular remodeling and have promise as therapeutics for vascularization applications. Towards development of EVs as therapeutics, it has been demonstrated that physiological stimuli of angiogenic phenotypes in EV-producing cells can enhance the potency of EVs for vascularization. The goal of this study was to assess whether ethanol, which induces angiogenic phenotypes in endothelial cells, could be employed to enhance endothelial-derived EV vascularization bioactivity. The results indicate that ethanol conditioning of endothelial cells increases the ability of endothelial EVs to induce a pro-vascularization response. This response is due in part to increased CD34 expression in recipient endothelial cells that may result from downregulation of microRNA-106b in EVs isolated from ethanol-conditioned producer endothelial cells. Further, ethanol-induced upregulation of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) HOTAIR and MALAT1 in endothelial EVs was observed to play a significant role in mediating pro-angiogenic effects of these vesicles. Overall, these studies validate ethanol conditioning as a method to enhance the bioactivity of endothelial EVs via regulation of EV-associated microRNAs (miRNAs) and, especially, lncRNAs. Further, the results suggest that alcohol consumption may activate endothelial EVs towards a pro-vascularization phenotype, which could have implications for alcohol-induced tumor angiogenesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Extracellular vesicles (EVs), including exosomes, microvesicles and other subtypes of cell-derived vesicles, have emerged as both critical mediators of intercellular communication as well as potential therapeutic vectors for a variety of applications1,2,3. Among the myriad applications and physiological systems in which EVs have been explored, their roles in angiogenesis and vascular remodeling are some of the most consistently reported. The physiological relevance of EVs in mediating vascular cell-cell communication and remodeling has been established4,5,6,7,8, and EVs have been applied for therapeutic vascularization in a number of settings9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. This use of EVs as therapeutics for vascularization is especially intriguing, as EVs may offer a combination of properties that could overcome some limitations associated with conventional cell-based and molecular therapeutics for this application. Specifically, compared to molecules, EVs are multifactorial vectors capable of stimulating multiple signaling and gene regulation pathways, while compared to cells, EVs have defined half-lives and clearance pathways and are not capable of uncontrolled division or differentiation. Further, EVs have been shown to mediate the paracrine pro-angiogenic effects of cells18.

However, EVs also have limitations as therapeutic vectors. Specifically, they may have low potency due to low microRNA (miRNA) content per vesicle19, given that miRNAs have been identified as crucial components mediating vascularization bioactivity of EVs14,16,17. Methods to enhance the potency of EVs have been developed, including exogenous loading approaches20,21,22,23,24,25,26 and cell conditioning via exposure to hypoxia or growth factor stimulation17,27,28. However, these approaches may not be easily adaptable to large-scale biomanufacturing of therapeutic EVs for vascularization applications, thus limiting translational potential.

One substance that may be straightforwardly incorporated into scalable EV production that also induces a pro-vascularization phenotype in endothelial cells is ethanol29,30,31. Ethanol is already part of large-scale biotechnology production schemes and is relatively cheap and readily available compared to purified growth factors. Ethanol has been shown to induce angiogenic endothelial phenotypes via a variety of pathways31,32,33,34 and has also been shown to influence the bioactivity and cargo of EVs in other cellular systems35,36. However, there are scarce reports of how ethanol effects on endothelial cells impact bioactivity of EVs derived from these cells.

We hypothesized that ethanol conditioning might increase the vascularization bioactivity of endothelial cell-derived EVs. In these studies, we sought to determine how cellular changes in endothelial cells induced by ethanol are manifested in EVs and to identify specific mechanisms of ethanol-induced regulation of endothelial cell EV activity. We report that ethanol increases the vascularization bioactivity of endothelial cell EVs through at least two distinct mechanisms: downregulation of anti-angiogenic miRNA cargo (miR-106b) and upregulation of pro-angiogenic long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) cargo (MALAT1 and HOTAIR). These findings have implications for generation of EVs for therapeutic vascularization applications and also may shed light on the role of EVs in alcohol-induced angiogenesis in cancer and other physiological settings.

Results

Ethanol stimulates EV production by endothelial cells

As a first step in evaluating the potential of ethanol conditioning as a means to enhance vascularization bioactivity of endothelial cell-derived EVs, the effects of ethanol on EV production were investigated. Concentrations of ethanol beyond 100 mM were found to induce significant cell toxicity in human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) (Fig. 1A), thus 100 mM was used as a maximum ethanol level in most experiments. The inclusion of ethanol in the culture medium did not appear to affect the structural integrity of produced EVs, as mean diameters (Fig. 1B) and protein expression levels (Fig. 1C,D) were found to be similar over the range between 0-200 mM ethanol for both HUVEC and human dermal microvascular endothelial cell (HDMEC) EVs (representative blots shown in Supplementary Fig. S1). Notably, up to ~2–3 fold increased EV production by endothelial cells was observed at higher ethanol concentrations (Fig. 1E,F).

Endothelial cell production of EVs in the presence of alcohol. (A) HUVEC survival was assessed with the indicated concentrations of ethanol (EtOH) included in growth medium (EGM2) (n = 3). (B) HUVEC EV size distribution in the presence or absence of the indicated concentrations of EtOH in the medium was assessed via NanoTracking Analysis (NTA) using a NanoSight LM10 (n = 3). Immunoblots for proteins associated with exosomes were performed for (C) HUVEC EVs and (D) HDMEC EVs isolated from producer cells cultured with the indicated EtOH concentrations. Blots shown are representative of three independent experiments. EV production rate by cells in medium containing the indicated EtOH concentrations was determined by NTA for (E) HUVEC and (F) HDMEC; n = 3, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 compared to 0 mM EtOH condition.

Ethanol conditioning increases endothelial cell-derived EV vascularization bioactivity

Following from the original hypothesis and given that structurally intact EVs were produced by endothelial cells in the presence of ethanol, EV vascularization bioactivity was directly assessed in vitro using an endothelial cell gap closure assay and in vivo using a Matrigel plug injection mouse model. EVs isolated from both HUVECs (Fig. 2A) and HDMECs (Fig. 2B) showed increased stimulation of endothelial gap closure based on the ethanol concentration used to condition the EV-producing cells. Additionally, ethanol conditioning (100 mM) endowed endothelial cell-derived EVs with increased ability to recruit host CD31+ cells into injected Matrigel plugs in C57Bl/6 mice (Fig. 2C,D). Together, these data demonstrate increased vascularization bioactivity of EVs derived from endothelial cells cultured in the presence of ethanol compared to those isolated from endothelial cells without ethanol conditioning.

Ethanol conditioning increases endothelial cell-derived EV vascularization bioactivity. Gap closure by (A) HUVECs and (B) HDMECs was assessed following stimulation by 100 µg/ml EVs isolated from the same producer cell type in medium with the indicated ethanol (EtOH) concentrations (n = 3, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. 0 mM EtOH condition); HUVECs incubated in basal medium (EBM2, without growth factors) were used as the negative control (−) and HUVECs incubated in growth medium (EGM2, with growth factors) were used as positive controls (+). (C) Matrigel plugs injected into C57Bl/6 mice containing PBS as a negative control (−) or 100 µg HUVEC EVs from cells cultured with the indicated concentrations of EtOH in the media were removed 10 d after implantation and CD31+ cells were quantified using immunohistochemical staining (n = 6; **P < 0.01 compared to all other groups by one-way ANOVA). Data are presented as %CD31+ stained cells out of all cells counted for the gel sections from a given animal. (D) Representative gel images and immunohistochemistry sections from animals in the indicated groups are shown (n = 6).

To determine the specific mechanism of the enhanced vascularization bioactivity of endothelial cell-derived EVs induced by ethanol conditioning of producer endothelial cells, we first profiled gene expression in recipient endothelial cells upon stimulation with EVs isolated from producer endothelial cells cultured in the presence or absence of 100 mM ethanol. Among 92 genes examined that are associated with angiogenic activity, a majority (68 of 92) were upregulated upon stimulation by EVs from ethanol-conditioned HUVECs compared to unconditioned HUVEC-derived EVs (Fig. 3A, Supplementary Table S1). The mRNA of CD34, a sialomucin protein associated with endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis37, was the most significantly differentially regulated (upregulated ~5 fold). This finding was confirmed independently by qPCR using different primers in both HUVECs and HDMECs (Fig. 3B).

CD34 is upregulated in endothelial cells (ECs) stimulated by EVs from ethanol (EtOH)-conditioned ECs. (A) Experimental schematic and representation of gene regulation profile of 92 genes associated with angiogenesis. Data shown represent mRNA levels in recipient HUVECs stimulated by 100 µg/ml EVs from producer HUVECs cultured in the presence vs. the absence of 100 mM EtOH for 24 h. (B) CD34 expression in recipient HUVECs and HDMECs following stimulation by 100 µg/ml EVs from producer ECs of the same type cultured in the presence or absence (control (Ctrl)) of 100 mM EtOH for 24 h was assessed by qPCR using distinct primers from those in the mRNA array (n = 3; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

Ethanol conditioning regulates endothelial cell-derived EV miRNA content

To determine the specific cause of the measured CD34 upregulation, EV-associated protein signaling and miRNA-mediated information transfer were examined, as proteins can be integrated within EV membranes to induce receptor-mediated signal transduction while miRNAs are among the most prevalent and biologically significant components of EV cargo1,3. Assessment of phosphorylation of 49 common receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) (Supplementary Table S2) that might be activated by ectodomains of EV-associated proteins did not reveal any significant differences between groups (Fig. 4A). This finding was partially confirmed by independent immunoblots for the phosphorylated versions of two RTKs that were stimulated to the greatest degree in this experiment, epidermal growth factor receptor (pEGFR) and insulin receptor (pIR) (Fig. 4B).

Endothelial cell receptor tyrosine kinase stimulation by EVs. (A) Phosphorylated RTK arrays were incubated for 30 min with lysates from recipient HUVECs stimulated by 100 µg/ml EVs from producer HUVECs cultured in the presence or absence of 100 mM ethanol (EtOH) for 24 h. Ovals indicate phospho-epidermal growth factor receptor (pEGFR) and rectangles indicate phosphor-insulin receptor (pIR). Blots shown are representative of three independent experiments. (B) The same conditions were used to generate separate immunoblots for pEGFR and pIR using different antibodies (n = 3; H1975 cells were used as a positive control for pEGFR (+)).

Potential EV-mediated miRNA regulation of CD34 expression was assessed using a luciferase reporter assay, where the 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of CD34 was cloned into a luciferase vector that was subsequently transfected into HUVECs. EVs from HUVECs cultured in the presence or absence of 100 mM ethanol were then applied to recipient HUVECs, and detection of miRNA-specific targeting of CD34 for downregulation was performed based on quantification of luciferase expression. The results of this assay indicated that EVs from non-conditioned producer HUVECs contain miRNAs that specifically target CD34 for downregulation in recipient cells, as these EVs induced a 16.7+/−3.3% reduction in luciferase activity compared to control (Fig. 5A). However, EVs from HUVECs cultured in the presence of 100 mM ethanol induced only a 2.3+/−2.5% reduction in luciferase activity (Fig. 5A), suggesting that ethanol conditioning of HUVECs alters EV miRNA content resulting in reduced CD34 degradation.

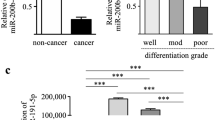

Ethanol (EtOH) regulates endothelial cell-derived EV microRNA content. (A) Luciferase expression in recipient HUVECs from a construct containing the 3′ untranslated region of CD34 was measured by bioluminescence imaging following stimulation by 100 µg/ml EVs from producer HUVECs cultured in the presence of the indicated concentrations of EtOH for 24 h (n = 4; **P < 0.01 vs. 0 mM EtOH condition, ##P < 0.01 vs. positive control (+) condition). Mock-transfected HUVEC not exposed to EVs were used as negative controls (−), while transfected HUVEC not exposed to EVs were used at the positive control (+). (B) Average whole miRNome array results comparing miR content of EVs derived from HUVEC cultured in the presence or absence of 100 mM EtOH for 24 h (n = 3). Red dots indicate upregulation of miRs and green dots indicate downregulation of miRs in HUVEC EVs based on producer cell EtOH exposure. Black dots indicate similar expression levels. (C) Expression levels of the indicated microRNAs (miRs) in endothelial cell EVs from producer cells cultured in the presence vs. absence of 100 mM EtOH for 24 h was determined by qPCR (n = 3). (D) Gap closure of HUVECs was assessed upon stimulated by EVs derived from HUVECs cultured in the absence (−EtOH) or presence (+EtOH) of 100 mM EtOH for 24 h following mock transfection or transfection by an antagomir to miR-106b (anti-miR-106b) or a scrambled oligo sequence (anti-miR-scr) (n = 3; ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01 vs. EVs (−EtOH) group). HUVECs incubated in basal medium (EBM2, without growth factors) were used as the negative control (−) and HUVECs incubated in growth medium (EGM2, with growth factors) were used as positive controls (+).

Towards identifying specific miRNA participants in this effect, analysis of the whole miRNomes of EV populations isolated from HUVECs cultured in the presence or absence of 100 mM ethanol was conducted. These studies revealed significant differences in miRNA content between the EV groups (Fig. 5B, Supplementary Table S3), including substantial downregulation of several miRNAs that are reported to negatively regulate angiogenesis, such as miR-57338, miR-13739, miR-320e40, and others. Further investigation of miRNAs that have been validated to target CD34 for downregulation, including miR-106b41, miR-125a42 and miR-942, showed that miR-106b was downregulated > 5 fold in EVs from both HUVECs and HDMECs cultured in the presence of 100 mM ethanol compared to cells cultured without ethanol (Fig. 5C). To confirm the specific role of miR-106b, HUVECs (in the absence of ethanol) were transfected with an antagomir that was validated to significantly decrease miR-106b expression in HUVEC-derived EVs (Supplementary Fig. S2), recapitulating a specific effect of ethanol conditioning. Assessment of the vascularization bioactivity of these EVs, derived from non-ethanol-conditioned HUVECs but with diminished levels of miR-106b, showed increased ability to induce endothelial gap closure compared to control non-conditioned HUVEC EVs as well as HUVEC EVs from cells transfected with a scrambled antagomir sequence (Fig. 5D). Thus, specific downregulation of miR-106b partially recapitulated a significant phenotypic effect of ethanol conditioning on endothelial cell-derived EVs. Overall, these data point to regulation of miR-106b as a crucial component of the mechanism of enhancement of endothelial cell-derived EV vascularization bioactivity by ethanol conditioning.

Ethanol conditioning regulates endothelial cell-derived EV long non-coding RNA content

The ethanol-induced downregulation of miRNAs that negatively regulate angiogenesis is not necessarily sufficient to induce pro-vascularization bioactivity in endothelial cell EVs. To assess additional possible molecular players, long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) content in EVs was investigated, as lncRNAs have been reported as EV cargo components43. Specifically, lncRNAs known to induce angiogenesis via regulation of endothelial cell function, including HOTAIR44, MALAT145, and TUG145,46 were assessed by qPCR. Both HOTAIR and MALAT1 were significantly upregulated in EVs from HUVECs cultured in the presence of 100 mM ethanol (Fig. 6A). To assess specific roles of these lncRNAs, an approach similar to that described for miR-106b was used. In this case, HUVECs were transfected with siRNA specific to either HOTAIR (Fig. 6B), MALAT1 (Fig. 6C), both HOTAIR and MALAT1 (double transfection, Fig. 6D) or a scrambled siRNA sequence. The depletion of HOTAIR and MALAT1 from cellular RNA and EV RNA was confirmed by q-PCR (Supplementary Figs S3 and S4). The cells were then cultured in the presence or absence of 100 mM ethanol and assessment of the vascularization bioactivity of the EVs isolated from these groups of cells was conducted using endothelial gap closure assays. These experiments revealed that downregulating MALAT1 expression alone and MALAT1 and HOTAIR expression together significantly abrogated the increase in vascularization bioactivity in HUVEC EVs associated with ethanol conditioning (Fig. 6C,D). Overall, these data indicate that lncRNA regulation is a crucial aspect of ethanol-induced effects on endothelial cell EV bioactivity.

Ethanol regulates endothelial cell-derived EV lncRNA content. (A) Expression levels of the indicated lncRNAs were assessed by qPCR in EVs from HUVECs cultured in the presence vs. absence of 100 mM EtOH for 24 h (n = 3; *P < 0.05). (B–D) HUVEC gap closure was assessed following 24 h stimulation by 100 µg/ml EVs from HUVECs cultured in the absence (−EtOH) or presence (+EtOH) of 100 mM EtOH for 24 h following transfection with a scrambled siRNA (scr) or siRNA specific to (B) HOTAIR, (C) MALAT1, or (D) both HOTAIR and MALAT1 (double transfection) (n = 4; ##P < 0.01 vs. – EtOH+ scr; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. +EtOH+ scr). HUVECs incubated in basal medium (EBM2, without growth factors) were used as the negative control (−) and HUVECs incubated in growth medium (EGM2, with growth factors) were used as positive controls (+).

Discussion

This study establishes, for the first time, that ethanol induces enhanced vascularization bioactivity in endothelial cell-derived EVs. Regulation of both EV-associated miRNAs and lncRNAs by ethanol conditioning of producer cells contributes to this effect, which has potential ramifications for therapeutic EV biomanufacturing. These data also suggest that EVs may play an important role in the mechanism of alcohol-induced angiogenesis in cancer.

The finding that miRNAs were regulated in this study is not surprising, as miRNA content has been consistently linked to EV vascularization bioactivity14,16,17 and ethanol exposure has been specifically linked to regulation of EV miRNAs35,36. However, the upregulation of CD34 expression in recipient endothelial cells resulting from ethanol-induced regulation of endothelial cell EV miRNA cargo is interesting and suggests that ethanol exposure may induce transformation of quiescent endothelial cells into angiogenic tip cells via EVs37. Also unexpected was the finding that ethanol conditioning impacts endothelial cell EV bioactivity via regulation of lncRNA cargo, specifically HOTAIR and MALAT1. LncRNAs are reported to constitute a much smaller proportion of total nucleic acid cargo of EVs when compared to miRNAs43. Yet, our results establish that these molecules may play significant roles in defining EV vascularization bioactivity, supporting other studies that have identified bioactive lncRNAs in EVs47,48. Ethanol-induced regulation of pro-angiogenic lncRNA is not unprecedented; MALAT1 has been found to be upregulated in brains of human alcoholics49. However, to our knowledge, this is the first report connecting EV-associated MALAT1 with angiogenic bioactivity. Thus, more extensive study of the effects of ethanol on lncRNA expression in endothelial cells and their EVs may be of interest. Further, therapeutic loading of lncRNAs such as MALAT1 into EVs may be a promising strategy for enhancing vascularization bioactivity.

Finally, as previously stated, the finding that ethanol increases the angiogenic bioactivity of endothelial cell EVs has important implications in cancer. Alcohol consumption has been identified as a risk factor for several cancers, with the links between alcohol and breast and liver cancers being particularly strong. For example, epidemiological studies have consistently shown that breast cancer risk increases with alcohol intake50,51,52,53. Among many potential mechanisms, alcohol-induced tumor angiogenesis has been identified as a possible driver of breast cancer progression33,34, with several signaling pathways in endothelial cells being implicated30,31. While activation of these pathways is typically associated with proteins, this study suggests that alcohol exposure to endothelial cells could induce production of pro-angiogenic EVs, which could potentially promote progression of latent tumors (Fig. 7). This possibility is further supported by reports that EVs have been shown to stimulate tumor angiogenesis7,9,10,18,54,55. Thus, the results of this study support further exploration of the potential mechanistic role of endothelial cell-derived EV regulation in alcohol-induced cancer progression.

In summary, this study demonstrates that the pro-angiogenic effects of ethanol on endothelial cells increase the vascularization bioactivity of EVs derived from these cells. This is accomplished in part by regulation of both miRNA and lncRNA components of EVs, with miR-106b downregulation and MALAT1 upregulation having significant effects. These findings could inform future mechanistic studies of the role of EVs in alcohol-induced cancer progression and may also identify new therapeutic cargo or quality control parameters for large-scale biomanufacturing of EVs for therapeutic vascularization applications.

Methods

Cell culture

HUVEC and HDMEC were obtained from Promocell and were generally cultured in EGM2 medium (with growth factors) (Lonza). In gap closure experiments, EBM2 media (without growth factors) (Lonza) was used as the basal medium. All media were filter sterilized and depleted of serum-derived EVs prior to use by centrifuging complete media at 100,000 × g for 16 h at 4 °C. For all experiments involving ethanol conditioning, cells were incubated in medium containing ethanol at the indicated concentration for 24 h.

EV isolation and characterization

To isolate EVs, ~2 × 106 cells were seeded into T175 flasks and allowed to incubate for 24 h or until ~50% confluent. Medium was then aspirated, cells were washed once with 20 ml of pre-warmed 1X PBS, and 35 ml of pre-warmed EV-depleted medium with or without ethanol was added to the flask. Cells were incubated until ~90% confluent, medium was collected and differential centrifugation was employed to isolate EVs as previously described20. The concentration and size of vesicles were measured by NanoTracking Analysis (NTA) using a NanoSight LM10 (Malvern). EVs were diluted 40X in 1X PBS prior to measurement. RNA was isolated from EVs by addition of 700 µl of QIAzol reagent (Qiagen) directly into Optiseal tubes following differential centrifugation prior to resuspending the EV pellet. RNA was then purified using the miRNeasy mini kit (Qiagen #217004) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For mRNA and lncRNA isolation, RNeasy Mini kits (Qiagen #74104) were used. RNA was quantified using a nanospectrophotometer and RNA integrity was assessed by running samples in 15% TBE-Urea gels.

Total protein present in EV samples was determined using the BCA assay (Pierce #23225). Proteins present in EVs were tested by immunoblotting as described previously21. Alix, CD9 and GAPDH antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling; TSG101 (sc-7964) and CD63 (sc-5275) antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Odyssey blocking buffer from LI-COR (catalog # 927-40000) was used for blocking and incubation. Primary and secondary antibodies were diluted 1:1,000 and 1:10,000 in 0.5X blocking buffer. Densitometry was performed using Licor Odyssey software.

Vascularization bioactivity

To assess vascularization bioactivity in vitro, an endothelial gap closure assay was used. 30,000 HUVECs were plated in the wells of gelatin-coated 48-well plates. After 24 hours of incubation in complete EGM2, a scratch was made in each of the wells using the tip of a 200 µl micropipette. Medium was aspirated and the cells were then washed first with 300 µl of 1X PBS and then with 300 µl of EBM2 medium. As positive and negative controls, EGM2 (complete medium) and EBM2 (basal medium) were used. Cells were treated with EVs to make the final concentration of EVs 100 µg/ml based on EV protein quantification. Images were taken of the scratches after 0, 9 and 15 h, and the denuded areas were quantified using ImageJ software. Data reported are for the 15 h time point.

To assess bioactivity in vivo, a Matrigel plug assay was performed as described previously29. Briefly, 0.4 mL Matrigel (Corning #356231) with or without 100 µg of EVs (in 100 µl PBS) from HUVECs cultured in the presence or absence of 100 mM ethanol was injected subcutaneously into the ventral area of C57Bl/6 mice. After 10 days, mice were euthanized and the Matrigel plugs were excised and fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin before embedding in paraffin and sectioning for histological (hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)) and immunohistochemical analysis. All animal experiments were carried out following protocols approved by the University of Maryland IACUC.

Immunohistochemical analysis

Sections were affixed to glass slides and deparaffinized in xylene, dehydrated in graded alcohol, and finally hydrated in water. Antigen retrieval was performed by boiling the slides in TE buffer (pH 9.0) for 30 min. CD31 primary antibody (Abcam # ab8364) and goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L secondary antibody (Abcam # ab6719) were used in 1:100 and 1:200 dilutions respectively. After incubation with the primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight, the slides were incubated with peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG and stained with diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogen solution (SK-4105) (both from Vector Laboratories), and then counterstained with hematoxylin. Images were taken with an Olympus BX51 microscope. The percentage of cells with CD31+ was determined by counting the total number of cells and CD31+ cells from each gel section.

RNA profiling and analysis

Human miRNome miScript miRNA arrays (V16.0, 384-well, SA Biosciences, # MIHS-3216ZE) were used to identify the level of miRNAs in EVs from HUVECs cultured in the presence or absence of 100 mM ethanol. EV RNA was isolated by using miRNeasy mini kits (Qiagen #217004) and cDNA was prepared using miScript II RT kits (Qiagen #21860). As recommended in the protocol, ~350 ng of RNA sample was used to make cDNA for one 384-well plate. The miScript miRNA PCR array reaction volume was kept to 10 μl per well for 384-well plate. PCR was performed using an Applied Biosystems Real Time PCR instrument (ABI 7900 Fast HT) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Finally, data were analyzed using SA Biosciences software: (http://sabiosciences.com/mirnaArrayDataAnalysis.php).

Profiling of mRNAs associated with angiogenesis was carried out in recipient HUVECs exposed to EVs isolated from producer HUVECs cultured in the presence or absence of 100 mM ethanol for 24 h. Quantitative PCR using an ABI 7900 Fast HT machine and employing SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) was used to detect RNA levels in the context of an Angiogenesis PCR array kit (Bio-Rad H384), with settings as recommended for the Supermix reagent. Data were analyzed using the ΔΔCt method. β-actin mRNA and TUG1 lncRNA were selected as controls that were not expected to be affected in control vs. ethanol samples. The sequences of qPCR primers used for this study are available by request.

miRNA activity assay

To evaluate miRNA targeting of CD34, a pMirTarget reporter plasmid (Origene, catalog# SC213155) containing the coding sequence for the 3′-UTR of CD34 downstream of firefly luciferase was used. The plasmid was transfected into HUVECs that were plated in 12-well plates 24 h prior to transfection using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). After an additional 24 h period, transfected HUVECs were exposed to control solution (PBS) or EVs (100 μg/ml final concentration) from producer HUVECs cultured in the presence of absence of 100 mM ethanol. Cells were harvested after 48 h and lysate was prepared using Luc-Pair™ Duo-Luciferase Assay Kit 2.0 (Genecopoeia#LPFR-P010) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and normalized luciferase levels were determined using a SpectraMax Gemini plate reader.

Protein detection

Receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) phosphorylation was investigated using Proteome Profiler Human Phospho-RTK Arrays (R&D Systems #ARY001B). HUVECs were incubated with 100 µg/ml EVs isolated from HUVECs cultured in the presence or absence of 100 mM ethanol for 30 min and a total protein lysate was prepared and applied to antibody pre-coated membranes according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The expression levels of pIR and pEGFR were assessed by standard immunoblotting using the following antibodies: pIR (Tyr 1162/1163) (Santa Cruz #sc-25103 P); pEGFR (Tyr1068) (Cell Signaling #2234 S).

Transfections

Transfection of HUVECs was performed when cells reached ~50% confluence using HiPerFect reagent (Qiagen #301704). The antagomir of miR-106b-5p (5′-AUC UGC ACU GUC AGC ACU UUA-3′) is a single RNA sequence exactly complementary to miR-106b-5p sequence and was purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies. The concentration of the miR-106b-5p antagomir and negative control was 10 nM. HUVECs mixed with only HiPerFect (mock transfected) and HUVECs transfected with scrambled RNA with HiPerFect were used as controls. After 48 h, cells were harvested and total RNA was prepared to quantify miR-106b-5p level. To measure miR106b-5p levels in EVs, media was collected after 48 h of transfection from T75 flask. The level of miR106b-5p was measured by q-PCR by using primers specific for miR106b-5p. After confirmation of miR106b-5p knockdown in both cells and EVs, a large-scale cell culture was made in T75 flasks and antagomir or scrambled oligo transfections were performed.

A similar approach was employed to knockdown HOTAIR and MALAT1 lncRNAs in HUVECs. TriFECTa RNAi kits against both lncRNAs were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT). A pool of three siRNAs or control siRNA was transfected by HiPerFect reagent and the final concentrations of transfected RNA oligos were 50 nM. The knockdown of HOTAIR or MALAT1 lncRNAs from cells and EVs was confirmed by q-PCR using primers specific for each lncRNA.

Statistical analysis

Parametric statistical tests (one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni post-hoc test, 2-sample t-test) were used as appropriate and statistical significance level is indicated for each figure where it was calculated. Data were plotted as mean +/− standard deviation.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

References

Andaloussi, E. L., Mager, I., Breakefield, X. O. & Wood, M. J. Extracellular vesicles: biology and emerging therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Drug Discov 12, 347–357, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd3978 (2013).

Lamichhane, T. N. et al. Emerging roles for extracellular vesicles in tissue engineering and regenerative medicine. Tissue engineering. Part B, Reviews 21, 45–54, https://doi.org/10.1089/ten.TEB.2014.0300 (2015).

Gyorgy, B., Hung, M. E., Breakefield, X. O. & Leonard, J. N. Therapeutic applications of extracellular vesicles: clinical promise and open questions. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology 55, 439–464, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010814-124630 (2015).

van Balkom, B. W. et al. Endothelial cells require miR-214 to secrete exosomes that suppress senescence and induce angiogenesis in human and mouse endothelial cells. Blood 121, 3997–4006, S3991–3915, https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-02-478925 (2013).

Deregibus, M. C. et al. Endothelial progenitor cell derived microvesicles activate an angiogenic program in endothelial cells by a horizontal transfer of mRNA. Blood 110, 2440–2448, https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2007-03-078709 (2007).

Hergenreider, E. et al. Atheroprotective communication between endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells through miRNAs. Nat Cell Biol 14, 249–256, https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb2441 (2012).

Salomon, C. et al. Exosomal signaling during hypoxia mediates microvascular endothelial cell migration and vasculogenesis. PLoS One 8, e68451, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068451 (2013).

Su, S. A. et al. Emerging role of exosome-mediated intercellular communication in vascular remodeling. Oncotarget 8, 25700–25712, https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.14878 (2017).

Bian, S. et al. Extracellular vesicles derived from human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells promote angiogenesis in a rat myocardial infarction model. Journal of molecular medicine (Berlin, Germany) 92, 387–397, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00109-013-1110-5 (2014).

Zhang, B. et al. Human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell exosomes enhance angiogenesis through the Wnt4/beta-catenin pathway. Stem cells translational medicine 4, 513–522, https://doi.org/10.5966/sctm.2014-0267 (2015).

Hu, G. W. et al. Exosomes secreted by human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells attenuate limb ischemia by promoting angiogenesis in mice. Stem cell research & therapy 6, 10, https://doi.org/10.1186/scrt546 (2015).

Vrijsen, K. R. et al. Exosomes from Cardiomyocyte Progenitor Cells and Mesenchymal Stem Cells Stimulate Angiogenesis Via EMMPRIN. Adv Healthc Mater 5, 2555–2565, https://doi.org/10.1002/adhm.201600308 (2016).

Liang, X., Zhang, L., Wang, S., Han, Q. & Zhao, R. C. Exosomes secreted by mesenchymal stem cells promote endothelial cell angiogenesis by transferring miR-125a. J Cell Sci 129, 2182–2189, https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.170373 (2016).

Mathiyalagan, P. et al. Angiogenic Mechanisms of Human CD34+ Stem Cell Exosomes in the Repair of Ischemic Hindlimb. Circ Res 120, 1466–1476, https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.310557 (2017).

Gonzalez-King, H. et al. Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1alpha Potentiates Jagged 1-Mediated Angiogenesis by Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes. Stem Cells, https://doi.org/10.1002/stem.2618 (2017).

Ranghino, A. et al. Endothelial progenitor cell-derived microvesicles improve neovascularization in a murine model of hindlimb ischemia. International journal of immunopathology and pharmacology 25, 75–85 (2012).

Gray, W. D. et al. Identification of therapeutic covariant microRNA clusters in hypoxia-treated cardiac progenitor cell exosomes using systems biology. Circ Res 116, 255–263, https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.304360 (2015).

Sahoo, S. et al. Exosomes from human CD34(+) stem cells mediate their proangiogenic paracrine activity. Circ Res 109, 724–728, https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.253286 (2011).

Chevillet, J. R. et al. Quantitative and stoichiometric analysis of the microRNA content of exosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111, 14888–14893, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1408301111 (2014).

Lamichhane, T. N., Raiker, R. S. & Jay, S. M. Exogenous DNA Loading into Extracellular Vesicles via Electroporation is Size-Dependent and Enables Limited Gene Delivery. Mol Pharm 12, 3650–3657, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00364 (2015).

Lamichhane, T. N. et al. Oncogene Knockdown via Active Loading of Small RNAs into Extracellular Vesicles by Sonication. Cellular and Molecular Bioengineering 9, 315–324 (2016).

Haney, M. J. et al. Exosomes as drug delivery vehicles for Parkinson’s disease therapy. J Control Release 207, 18–30, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.03.033 (2015).

Hung, M. E. & Leonard, J. N. A platform for actively loading cargo RNA to elucidate limiting steps in EV-mediated delivery. Journal of extracellular vesicles 5, 31027, https://doi.org/10.3402/jev.v5.31027 (2016).

Sterzenbach, U. et al. Engineered Exosomes as Vehicles for Biologically Active Proteins. Mol Ther, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.03.030 (2017).

O’Loughlin, A. J. et al. Functional Delivery of Lipid-Conjugated siRNA by Extracellular Vesicles. Mol Ther, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.03.021 (2017).

Alvarez-Erviti, L. et al. Delivery of siRNA to the mouse brain by systemic injection of targeted exosomes. Nat Biotechnol 29, 341–345, doi:nbt.1807 [pii]10.1038/nbt.1807 (2011).

Lopatina, T. et al. Platelet-derived growth factor regulates the secretion of extracellular vesicles by adipose mesenchymal stem cells and enhances their angiogenic potential. Cell communication and signaling: CCS 12, 26, https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-811X-12-26 (2014).

de Jong, O. G., van Balkom, B. W., Gremmels, H. & Verhaar, M. C. Exosomes from hypoxic endothelial cells have increased collagen crosslinking activity through up-regulation of lysyl oxidase-like 2. J Cell Mol Med 20, 342–350, https://doi.org/10.1111/jcmm.12730 (2016).

Jones, M. K., Sarfeh, I. J. & Tarnawski, A. S. Induction of in vitro angiogenesis in the endothelial-derived cell line, EA hy926, by ethanol is mediated through PKC and MAPK. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 249, 118–123, https://doi.org/10.1006/bbrc.1998.9095 (1998).

Gu, J. W. et al. Moderate levels of ethanol induce expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and stimulate angiogenesis. American journal of physiology. Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology 281, R365–372 (2001).

Morrow, D., Cullen, J. P., Cahill, P. A. & Redmond, E. M. Ethanol stimulates endothelial cell angiogenic activity via a Notch- and angiopoietin-1-dependent pathway. Cardiovasc Res 79, 313–321, https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvn108 (2008).

Wang, L. et al. Ethanol enhances tumor angiogenesis in vitro induced by low-dose arsenic in colon cancer cells through hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha pathway. Toxicol Sci 130, 269–280, https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfs242 (2012).

Wang, S. et al. Ethanol promotes mammary tumor growth and angiogenesis: the involvement of chemoattractant factor MCP-1. Breast Cancer Res Treat 133, 1037–1048, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-011-1902-7 (2012).

Lu, Y. et al. Alcohol promotes mammary tumor growth through activation of VEGF-dependent tumor angiogenesis. Oncol Lett 8, 673–678, https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2014.2146 (2014).

Momen-Heravi, F., Bala, S., Kodys, K. & Szabo, G. Exosomes derived from alcohol-treated hepatocytes horizontally transfer liver specific miRNA-122 and sensitize monocytes to LPS. Scientific reports 5, 9991, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09991 (2015).

Saha, B., Momen-Heravi, F., Kodys, K. & Szabo, G. MicroRNA Cargo of Extracellular Vesicles from Alcohol-exposed Monocytes Signals Naive Monocytes to Differentiate into M2 Macrophages. J Biol Chem 291, 149–159, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M115.694133 (2016).

Siemerink, M. J. et al. CD34 marks angiogenic tip cells in human vascular endothelial cell cultures. Angiogenesis 15, 151–163, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10456-011-9251-z (2012).

Danza, K. et al. MiR-578 and miR-573 as potential players in BRCA-related breast cancer angiogenesis. Oncotarget 6, 471–483 (2015).

Lu, Y. et al. miR-137 regulates the migration of human umbilical vein endothelial cells by targeting ephrin-type A receptor 7. Molecular medicine reports 10, 1475–1480, https://doi.org/10.3892/mmr.2014.2319 (2014).

Wang, X. et al. Cardiomyocytes mediate anti-angiogenesis in type 2 diabetic rats through the exosomal transfer of miR-320 into endothelial cells. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology 74, 139–150 (2014).

Linsley, P. S. et al. Transcripts targeted by the microRNA-16 family cooperatively regulate cell cycle progression. Mol Cell Biol 27, 2240–2252, https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.02005-06 (2007).

Garzon, R. et al. MicroRNA signatures associated with cytogenetics and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 111, 3183–3189, https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2007-07-098749 (2008).

Huang, X. et al. Characterization of human plasma-derived exosomal RNAs by deep sequencing. BMC Genomics 14, 319, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-14-319 (2013).

Fu, W. M. et al. Long noncoding RNA Hotair mediated angiogenesis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma by direct and indirect signaling pathways. Oncotarget 7, 4712–4723, https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.6731 (2016).

Michalik, K. M. et al. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1 regulates endothelial cell function and vessel growth. Circ Res 114, 1389–1397, https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303265 (2014).

Dong, R. et al. Targeting long non-coding RNA-TUG1 inhibits tumor growth and angiogenesis in hepatoblastoma. Cell death & disease 7, e2278, https://doi.org/10.1038/cddis.2016.143 (2016).

Takahashi, K., Yan, I. K., Kogure, T., Haga, H. & Patel, T. Extracellular vesicle-mediated transfer of long non-coding RNA ROR modulates chemosensitivity in human hepatocellular cancer. FEBS Open Bio 4, 458–467, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fob.2014.04.007 (2014).

Conigliaro, A. et al. CD90+ liver cancer cells modulate endothelial cell phenotype through the release of exosomes containing H19 lncRNA. Mol Cancer 14, 155, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-015-0426-x (2015).

Kryger, R., Fan, L., Wilce, P. A. & Jaquet, V. MALAT-1, a non protein-coding RNA is upregulated in the cerebellum, hippocampus and brain stem of human alcoholics. Alcohol 46, 629–634, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcohol.2012.04.002 (2012).

Singletary, K. W. & Gapstur, S. M. Alcohol and breast cancer: review of epidemiologic and experimental evidence and potential mechanisms. JAMA 286, 2143–2151 (2001).

Hamajima, N. et al. Alcohol, tobacco and breast cancer–collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 53 epidemiological studies, including 58,515 women with breast cancer and 95,067 women without the disease. Br J Cancer 87, 1234–1245, https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6600596 (2002).

Key, J. et al. Meta-analysis of studies of alcohol and breast cancer with consideration of the methodological issues. Cancer causes & control: CCC 17, 759–770, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-006-0011-0 (2006).

Allen, N. E. et al. Moderate alcohol intake and cancer incidence in women. J Natl Cancer Inst 101, 296–305, https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djn514 (2009).

Janowska-Wieczorek, A. et al. Microvesicles derived from activated platelets induce metastasis and angiogenesis in lung cancer. Int J Cancer 113, 752–760, https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.20657 (2005).

Shabbir, A., Cox, A., Rodriguez-Menocal, L., Salgado, M. & Badiavas, E. V. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Exosomes Induce Proliferation and Migration of Normal and Chronic Wound Fibroblasts, and Enhance Angiogenesis In Vitro. Stem cells and development 24, 1635–1647, https://doi.org/10.1089/scd.2014.0316 (2015).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding support from the National Institutes of Health (HL112905 to S.M.J.), the Elsa U. Pardee Foundation (to S.M.J.), the University of Maryland and the state of Maryland via MPowering the State seed funding (to S.M.J.). The authors thank Dr. Laura Bracaglia and Dr. John Fisher for assistance with preparation of slides for immunohistochemistry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.N.L. and S.M.J. conceived and designed the experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. T.N.L., C.A.L. and L.Y.D. performed experiments. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lamichhane, T.N., Leung, C.A., Douti, L.Y. et al. Ethanol Induces Enhanced Vascularization Bioactivity of Endothelial Cell-Derived Extracellular Vesicles via Regulation of MicroRNAs and Long Non-Coding RNAs. Sci Rep 7, 13794 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14356-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14356-2

This article is cited by

-

Potential role of the lncRNA "HOTAIR"/miRNA "206"/BDNF network in the alteration in expression of synaptic plasticity gene arc and BDNF level in sera of patients with heroin use disorder through the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway compared to the controls

Molecular Biology Reports (2024)

-

Extracellular Vesicles: Intercellular Mediators in Alcohol-Induced Pathologies

Journal of Neuroimmune Pharmacology (2020)

-

Adenosine receptors regulate exosome production

Purinergic Signalling (2020)

-

A treatise on endothelial biology and exosomes: homage to Theresa Maria Listowska Whiteside

HNO (2020)

-

Emerging role of exosome-derived long non-coding RNAs in tumor microenvironment

Molecular Cancer (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.