Abstract

Efficient recycling of subducted sedimentary nitrogen (N) back to the atmosphere through arc volcanism has been advocated for the Central America margin while at other locations mass balance considerations and N contents of high pressure metamorphic rocks imply massive addition of subducted N to the mantle and past the zones of arc magma generation. Here, we report new results of N isotope compositions with gas chemistry and noble gas compositions of forearc and arc front springs in Costa Rica to show that the structure of the incoming plate has a profound effect on the extent of N subduction into the mantle. N isotope compositions of emitted arc gases (9–11 N°) imply less subducted pelagic sediment contribution compared to farther north. The N isotope compositions (δ15N = −4.4 to 1.6‰) of forearc springs at 9–11 N° are consistent with previously reported values in volcanic centers (δ15N = −3.0 to 1.9‰). We advocate that subduction erosion enhanced by abundant seamount subduction at 9–11 N° introduces overlying forearc crustal materials into the Costa Rican subduction zone, releasing fluids with lighter N isotope signatures. This process supports the recycling of heavier N into the deep mantle in this section of the Central America margin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

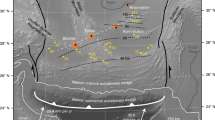

Subduction-zone fluids play a pivotal role in magma generation processes in arc settings. The release of fluids and volatiles from subducting slabs causes melting of the overlying mantle to produce arc magmas1,2. Mass balance relationships of geochemical processes have been used to understand subduction processes, recycling of chemical components, mantle heterogeneity, and climate effects3,4. As the Costa Rican subduction zone, a part of the Central American margin, has geochemical accessibilities to drilled oceanic samples, forearc fluid seeps, and volcanism on the arc front3,5,6,7,8,9 (Fig. 1), this area is an appropriated area to test geochemical mass balance relationships.

Map of the Costa Rican subduction zone. Sampled forearc (blue and yellow circles) and arc front (red circles) springs are shown. This map was created using GeoMapApp 3.6.4 (http://www.geomapapp.org). Volcanic centers (black triangles) are displayed: R (Rincon de la Vieja), M (Miravalles), A (Arenal), P (Poas), I (Irazu), T (Turrialba). The Cocos plate (CO) with seamounts and the Cocos Ridge (CR) are two major segments in the Costa Rican subduction zone. The subducting plate with seamounts and related scars at the frontal arc are shown at 9–11 N°.

Nitrogen (N), the most abundant gas component in air, is one of the major volatiles released by volcanism and hydrothermal activity to the atmosphere10. In subduction systems, N in magmatic volatiles reflects pelagic sediment input (δ15N = +7‰, ref.11) that is subducted with oceanic plates3,12,13,14. In the Central American margin, previously reported N isotope compositions of fumarole and hot spring gas discharges in Guatemala and Nicaragua show such a sediment contribution with δ15N values up to 6.3‰ 3,12. However, δ15N values of fumarole and hot spring gas samples in Costa Rica have been reported with a range from −3.0 to 1.7‰, suggesting more mantle N contribution (δ15N = −5‰, ref.11). This shows a lower fraction of sediment contribution compared to localities farther north3,6. Recycling efficiency of N in the Costa Rican subduction zone is low due to the small N outflux at the arc front compared to the N influx at the trench6. This observation has been attributed to off-scraping of sediments or forearc devolatilization of N at the Costa Rica subduction zone6. In other regions, a low efficiency of N recycling has been documented in the Sangihe Arc15 and in the Mariana Arc16. In these locations, sediment off-scraping or lack of organic sediment availability have been invoked as plausible causes for the comparatively low sedimentary N flux out of these volcanic arcs. In order to further constrain the notion of sediment off-scraping or underplating, trenchward regions, such as the forearc, are potential locations where such processes may be observed geochemically. In these areas, devolatilization of pelagic sediments could occur and potentially be sampled in associated springs and groundwaters. However, to date, N isotope compositions of forearc regions have not been measured rendering it impossible to fully constrain the nitrogen cycle at subduction zones.

In this work, we explore forearc regions with new results of N isotope compositions, gas chemistry, and helium isotopes of springs. Costa Rica is the ideal location to perform such a study because in contrast to most subduction zones the forearc is subaerial and accessible to sampling at Santa Elena, Nicoya, Osa, and Burica peninsulas (Fig. 1), where a number of springs are releasing volatiles. We also report new data from springs in the Costa Rica arc front.

Results

Gas chemistry

Forearc (T = 26.0–31.6 °C; pH = 7.0–11.1) and arc front springs (T = 26.1–72.6 °C; pH = 6.5–9.6) in Costa Rica were sampled in 2012 and 2014 (Fig. 1; Table 1). Based on gas compositions, forearc springs are subdivided into N2-rich (62.4–98.3 vol. %) and CH4-rich (36.1–96.8 vol. %) types, and arc front springs are subdivided into N2-rich (88.0–98.5 vol. %) and CO2-rich (47.2–98.4 vol. %) types (Supplementary Information). Although air contamination during sampling is minor based on low O2 contents (<2.3 vol. %) except for CR12-15, CR14-03, CR14-09B, CR12-05, and CR12-13(6.0–10.3 vol. %) (Supplementary Information), N2/Ar ratios for forearc (47–95) and arc front (30–146) springs are similar or slightly higher than ratios of air saturated water (ASW, 40) and air (83) (Table 2). N2/He and He/Ar ratios are higher than 1,000 and lower than 0.1, respectively, except for Cayuco (N2/He = 84; He/Ar = 0.8) which seems to have more mantle-derived volatiles (Table 2). In Fig. 2, the N2-Ar-He abundances show that volatiles in the Costa Rican springs are mostly atmospheric, except for two arc front springs (Cayuco and Rincon de la Vieja) with a higher proportion of mantle-derived components. Given that N2/Ar ratios are higher than ASW, N in excess of ASW (N2-exc) can be calculated. Ar contents are used to calculate N2-exc values based on the assumption that Ar in volcanic gases and geothermal fluids are mostly from ASW17,18. Using measured N2 and Ar contents and the N2/Ar ratio of ASW (40), N2-exc values are obtained as following19:

Ternary plot of N2-Ar-He abundances. Relative abundances of N2, Ar, and He in the forearc and arc front springs samples are used to show mixing relationships among the mantle, arc gases, air, and air saturated water (ASW). The forearc springs plot closer to the air-ASW components than the arc front springs which likely have either the mantle of arc gas end-members.

Calculated N2-exc contents and N2-exc/He ratios indicate N amounts in excess to what is supplied to the sampled water phase by N2 derived from air and then dissolved water (Table 2).

Nitrogen isotope compositions

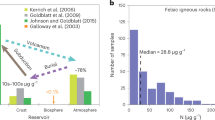

Nitrogen isotope compositions (δ15N vs air) of the Costa Rican springs range from −4.4 to 1.6‰ (9–11 N°), except for the Osa (4.7‰) and Burica (4.0‰) forearc springs located in the southernmost part of Costa Rica (8.4–8.6 N°) (Table 2; Fig. 3). The δ15N values of the springs are well consistent with the reported volcanic δ15N values (−3.0 to 1.9‰, refs3,6,20). In Fig. 3, both the forearc and arc front springs at 9–11 N° have less sediment (δ15N = 7‰) contribution than other Central American subduction zone samples (δ15N = −2.2 to 6.3‰) at > 11 N° (e.g., Nicaragua and Guatemala)3,12. The N sources are constrained following the approach of refs3,11 by using δ15N and N2/He ratios of the springs (Fig. 4a):

where fMORB, fsediment, and fair are fractions of three end-members (Mid Ocean Ridge Basalt (MORB), sediment, and air). δ15NMORB, δ15Nsediment, and δ15Nair, are −5‰, 7‰, and 0‰, and (N2/He)MORB, (N2/He)sediment, and (N2/He)air are 150, 10,500, and 148,900, respectively3,11,21,22,23,24,25. However, δ15N values (−2.8 to −0.7‰) of the Nicoya forearc springs and the arc front springs, which have been reported for the Sangihe and Nicaraguan arc systems15,16, are shifted towards values more negative than defined by the MORB-air mixing lines (Fig. 4a). In order to account for such negative values, kinetic fractionation processes related to gas bubbling through spring water26 and thermal decomposition of ammonia27 have been proposed, however, the fractionations associated with these processes (<1‰) are insufficient to explain the measured N isotope shift (Fig. 4a). For these reasons, N sources are constrained using the modified approach with N2-exc/He ratios following:

where (N2-exc/He)air is 78,023 by reducing the ASW proportion, and (N2/He)MORB and (N2/He)sediment are the same values as above because we do not expect any air-derived N in these end-members. In Fig. 4b. the δ15N and N2-exc/He of the Costa Rican springs and Nicaraguan gases12 are displayed showing that now most samples lie within the mixing curves. The air end-member in Fig. 4b now represents N2 addition from air in the atmosphere and not dissolved in the water phase. Sediment contribution (fsediment) to N of all Costa Rican springs ranges from 0 to 42%, except for the Osa (76%) and Burica (68%) springs (Supplementary Information). Additionally, most of the Costa Rican springs at 9–11 N° shows less sediment contribution compared to Guatemala (fsediment = 20–90%, ref.3) and Nicaragua (fsediment = 46–96%, ref.12) (Supplementary Information).

Nitrogen provenance diagram. (a) Nitrogen isotopes compositions versus N2/He ratios of the Costa Rican springs. End-members and mixing lines are defined as described in refs3,11. Percentages of sediment input are shown. The Nicaraguan data is from ref.12. (b) Nitrogen isotope compositions versus N2-exc/He, which displays a less number of data points (for both this study and ref.12) off the mix line between MORB and air. N2-exc/He of the air end-member was taken by reducing the ASW contribution.

Noble gas geochemistry

3He/4He and 4He/20Ne ratios of the Nicoya and Santa Elena forearc springs range from 0.61 to 1.09 Ra (Ra is (3He/4He) air = 1.382 × 10−6, ref.28) and 0.24 to 5.33, respectively (Table 2). One arc front spring near Rincon de la Vieja volcano (Fig. 1) has 3He/4He and 4He/20Ne ratios of 7.88 Ra and 20.0, respectively (Table 1), which is a typical feature of Costa Rican volcanic fluids5,6. As 40Ar/36Ar ratios (296.7 ± 7.5) are close to air (40Ar/36Ar = 295.5) (Supplementary Information), the 4He/20Ne ratios of dissolved gases in most of the spring samples are close to the ASW ratio (0.25 at 0 °C, ref.29). This implies that the atmospheric contribution is significant for noble gases. In order to linearly extrapolate to the source 3He/4He ratios of the dissolved gases, we use the 20Ne/4He ratios (Fig. 5) with the assumption that the source does not contain air-derived 20Ne. The extrapolated 3He/4He ratios fall between the MORB and crustal end members30,31,32. In Fig. 5, all the forearc springs plot on the line indicating 10% mantle helium similar to what has been measured in submarine seep fluids off the coast of Costa Rica8, implying that mantle fluids exist in the Nicoya and Santa Elena complexes.

Plot of helium isotope ratios (3He/4He) versus 20Ne/4He with three components are MORB, crust, and ASW. The Nicoya and Santa Elene forearc springs show the mixing relationship between ASW and the hybrid fluid with 10% MORB contribution. The arc front spring, located near the Rincon de la Vieja volcano (Fig. 1) is like the MORB component. The submarine seep fluids8 are also mixed by two components (ASW and deep fluids with > 10% MORB input).

Discussion

N isotope compositions (δ15N = −4.4 to 1.6‰) of all samples collected in Costa Rica (9–11 N°) indicate that lower proportions of N associated with pelagic sediments are released by most of the springs compared to Nicaragua (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Information). Costa Rican volcanic arc gases have a smaller fraction of samples which have δ15N values heavier than air (0‰) compared to Nicaragua (Figs 3 and 4)3,6. In Fig. 4b and Supplementary Information, the Nicoya forearc springs have less sediment fractions (fsediment = 0–3%) compared to the arc front springs (fsediment = 0–36%) implying that progressive N devolatilization of the subducted slab underneath Costa Rica is occurring. But, the N release from sediment into the Costa Rican arc is significantly less than in the Nicaraguan and Guatemalan arc sections where fsediment is 46–96%12 and 20–90%3, respectively. There are still outliers on the corrected N provenance diagram, and further studies are required to consider kinetic N isotope fractionation processes, such as denitrifying bacteria activities in forearc areas as proposed by ref.33.

Helium isotope ratios (3He/4He = 0.61–1.09 Ra) of the Nicoya and Santa Elena forearc areas are dominated by a crustal component. Lower 3He/4He ratios (<2 Ra) are common in other forearc springs, such as Japan, the North Island of New Zealand, and the Kamchatka peninsula of Russia18. In Fig. 5, the extrapolated end-member of helium isotope ratios can be determined because deep sources (higher 4He/20Ne ratios) without severe air contamination can be displayed on the y-intercept. Taking linear mixing lines with different MORB (8 Ra) and crustal (0.02 Ra)25 inputs into account, the Nicoya and Santa Elena forearc springs are mainly derived from crustal fluids with significant atmospheric contribution (Fig. 5). It has been known that basement rocks of Nicoya and Santa Elena are uplifted Caribbean large Igneous Province (CLIP) components which formed during Late Cretaceous associated with the Galapagos plume activity34. The crustal feature of 3He/4He ratios in forearcs could be ascribed to old basement rocks resulting in radiogenic 4He production by U-Th decay18.

There are also other lines of geochemical evidence that indicate weak sediment input in the Costa Rican subduction zone. Ba/La ratios of the Costa Rican lavas (<70) are lower than other Central American margin segments (e.g., Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Guatemala) which are up to ~130 (ref.35). Much lower contents of 10Be have been reported in the Costa Rican lavas than the Nicaraguan lavas36. Pb and Nd radiogenic isotopes imply that magma sources at the Costa Rican volcanic front are less likely affected by sediments37,38. Several models have been suggested to account for less sediment contribution in Costa Rica. First, uppermost sediments enriched in organic materials are removed by underplating39. This process would result in less N contribution into the arc systems. But, the ODP legs 170 and 205 of off-shore Costa Rica show pelagic sediments are in fact subducting beyond the trench7. Second, the shallower slab dip at Costa Rica having warmer thermal regime40 would result in N loss at shallow depths through forearc devolatilization as proposed by ref.41 based on exhumed metamorphic rocks. This model has been adopted to explain limited fluid availability due to fluids released by metamorphic reactions in the Costa Rican arc42,43,44. The proposed sediment-derived N loss at forearc depths is invalid because forearc springs in Nicoya and Santa Elena have only small sediment contributions (fsediment = 0–3%), though this may be a factor in the southernmost region of the arc (Osa and Burica samples). Finally, it is also unlikely that the incoming plate has a different composition and volume of sediments because off-shore Costa Rica has similar lithology and thickness (400 m) in sediments subducted into the trench (ODP site 1039) to off-shore Guatemala (DSDP site 495)7,9.

The subduction erosion model invokes the removal of continental material at the frontal or basal areas of continental margins. At the Costa Rican subduction zone, this model has been advocated by refs37,45,46,47,48,49. Compared to the Nicaragua and Guatemalan segments, Costa Rica has abundant seamounts on the Cocos plate at 9–11 N° (Fig. 1)48, which could enhance basal subduction erosion to have less signals of pelagic sediments36,37. In addition, scars observed in the upper plate in the frontal arc in Costa Rica are caused by seamount subduction colliding with the overriding plate50 (Fig. 1).

This model can explain observed N isotope variations in the Costa Rica forearc and arc front. N isotope compositions of the Costa Rican springs at 9–11 N° (δ15N = −4.4 to 1.6‰) and reported values of volcanic arc gases (δ15N = −3.0 to 1.9‰, refs3,6,20) are well consistent with the ranges of low-grade serpentinites (δ15N = 0.6 ± 3.4‰) and oceanic crust (δ15N = −1.2 ± 3.7‰)51. These values are consistent with the observation that the Nicoya and Santa Elena forearc areas are ophiolite complexes at the western edge of the CLIP52,53,54. Although the range of δ15N values is close to the MORB value (−5‰), noble gases indicate that the N sources of forearc springs could be crustal (Fig. 5). Hence, the ophiolitic materials which could preserve the MORB-derived N are likely the primary N source in Nicoya and Santa Elena forearc springs. In Fig. 3, most of arc front springs and volcanic gases3,6 are slightly heavier than the Nicoya and Santa Elena springs. This slight difference between forearc and arc front springs is likely due to increased δ15N values during progressive devolatilization resulting in decrease of 14N in the remaining materials7. Seamount subduction is not observed at < 9 N° at the Osa and Burica peninsulas consistent with heavier δ15N values of the Osa and Burica springs, which is likely attributed to a smaller degree of subduction erosion in this region.

Globally, there are other areas associated with seamount subduction, such as the Sangihe (δ15N = −7.3 to 2.1‰, ref.15) and Mariana (δ15N = −2.5 to 1.6‰, ref.16) arcs where 15N depleted signatures have been documented. The bathymetry of the Molucca sea floor in front of the Sangihe arc is not as smooth as nearby Celebes sea and Philippine sea plates due to the central ridge56. Also, the bathymetric map of the northwest Pacific57 shows that the ocean floor is rough with numerous seamounts in front of the Mariana subduction zone. Therefore, the subduction erosion of serpentinized overlying materials (e.g., low-grade serpentinite) enhanced by seamount subduction could result in contribution of N with the ranges of δ15N values reported in ref.51. Then, N from the upper plate materials could be the source releasing fluids with lighter N isotope compositions, which causes the N mass imbalance at the Costa Rican arc and transports heavier N into the deep mantle as suggested by refs7,58,59.

Conclusions

We report the first N isotopes compositions in the Costa Rican forearc and new N isotopes for arc springs to account for 15N-depleted signatures at the Costa Rican arc. Similar to the N isotope compositions reported in volcanic arc gases3,6,20, both forearc and arc front springs at 9–11 N° display a similar range of δ15N values. In comparison with other tectonic models for the limited amounts of sediment-derived N release (e.g., off-scraping, shallower slab dip, and different lithology and thickness in sediments), the subduction erosion enhanced by seamount subduction at 9–11 N° is a better choice to explain our observations. The δ15N values fall within the range of low-grade serpentinite or altered oceanic crust, which is consistent with the observation that the Nicoya and Santa Elena areas have oceanic floor materials formed by the Galapagos plume activity during Late Cretaceous. The seamounts subduction incorporates the overlying plate materials into the arc to release fluids with lighter N isotope values, and progressive devolatilization for N occurs from forearc to arc front. The release of 15N-depleted volatiles supports the deep recycling of heavier N at the Costa Rican subduction system.

Methods

Sampling and gas geochemistry

The Costa Rican forearc (Nicoya, Santa Elena, Osa, and Burica) and arc front springs were sampled in 2012 and 2014 (Table 1). Spring samples were collected and stored in pre-evacuated Giggenbach bottles, leaving headspaces for gas analyses. Concentrations of gas components (e.g., N2, Ar, He, and so on) were obtained in the Volatiles Laboratory at the University of New Mexico (UNM), and the general procedures are described in ref.60. He, Ar, O2, and N2 were measured in dynamic mode on a Pfeiffer Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer (QMS, analytical errors < 1%) with a mass range from 0 to 120 amu and a secondary electron multiplier detector. CO2, CH4, H2, Ar + O2, N2, and CO contents were determined using a Hayes Sep pre-column and 5 Å molecular sieve columns on a Gow-Mac series G-M 816 Gas Chromatograph (GC, analytical errors < 2%) with a helium carrier gas. A discharge ionization detector was used for CO2, CH4, H2, Ar+O2, N2 and CO. Concentrations of all gas components were acquired after merging the data from QMS and GC (whole results in Supplementary Information).

Isotope analyses

Determination of N isotope compositions was conducted using splits of gas samples taken into glass tubes and sealed on high vacuum lines. We neglected the mass interference by carbon monoxide based on its low concentrations (Supplementary Information). Then, N isotope compositions were analyzed on a Thermo Delta V Plus isotope ratio mass spectrometer (IRMS) with a gas bench in the center for Stable Isotopes at UNM. A tube-breaker and a six-way valve were used to break sealed glass tubes and inject N into the IRMS as describe in ref.61. Experimental errors (1σ = 0.1‰) for δ15N were obtained using multiple measurement of air samples (δ15N = 0‰). Argon isotope ratios (40Ar/36Ar) were determined in static mode on QMS after purification using a cold trap (at liquid N temperature) and hot titanium getters (at 550 °C) in the Volatiles Laboratory at UNM. Cu tubes were used for helium isotope analyses because helium can penetrate the glass containers (e.g., Giggenbach bottle). 3He/4He ratios were acquired by a Helix-SFT noble gas mass spectrometer at the Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute of the University of Tokyo (AORI). He and Ne were purified using hot titanium getters (held at 400 °C) and charcoal traps (at liquid N temperature) and 4He/20Ne ratios were obtained by an on-line QMS. After that, neon was trapped using a cryogenic trap (at 40°K). Experimental errors (1σ) for and 3He/4He and 4He/20Ne ratios are about 1% and 5%62.

References

Arculus, R. J. Aspects of magma genesis in arcs. Lithos 33, 189–208 (1994).

Iwamori, H. Transportation of H2O and melting in subduction zones. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 160, 65–80 (1998).

Fischer, T. P. et al. Subduction and recycling of nitrogen along the Central American margin. Science 297(5584), 1154–1157 (2002).

Hilton, D. R., Fischer, T. P. & Marty, B. Noble gases and volatile recycling at subduction zones. In: Noble Gases in Geochemistry and Cosmochemistry. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry 47 (eds Porcelli, D., Ballentine, C. J. &Wieler, R.) 319–370 (Mineralogical Society of America 2002).

Shaw, A. M., Hilton, D. R., Fischer, T. P., Walker, J. A. & Alvarado, G. E. Contrasting He–C relationships in Nicaragua and Costa Rica: insights into C cycling through subduction zones. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 214, 499–513 (2003).

Zimmer, M. M. et al. Nitrogen systematics and gas fluxes of subduction zones: Insights from Costa Rica arc volatiles. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 5, (5) (2004).

Li, L. & Bebout, G. E. Carbon and nitrogen geochemistry of sediments in the Central American convergent margin: insights regarding subduction input fluxes, diagenesis, and paleoproductivity. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 110, (B11) (2005).

Füri, E. et al. Carbon release from submarine seeps at the Costa Rica fore arc: Implications for the volatile cycle at the Central America convergent margin. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 11, (4) (2010).

Freundt, A. et al. Volatile (H2O, CO2, Cl, S) budget of the Central American subduction zone. Int. J. Earth. Sci. (Geol Rundsch) 103, 2101–2127, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00531-014-1001-1 (2014).

Rubey, W. W. Geologic history of sea water an attempt to state the problem. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 62, 1111–1148 (1951).

Sano, Y., Takahata, N., Nishio, Y., Fischer, T. P. & Williams, S. N. Volcanic flux of nitrogen from the Earth. Chem. Geol. 171, 263–271 (2001).

Elkins, L. J. et al. Tracing nitrogen in volcanic and geothermal volatiles from the Nicaraguan volcanic front. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 70, 5215–5235 (2006).

Agusto, M. et al. Gas geochemistry of the magmatic-hydrothermal fluid reservoir in the Copahue–Caviahue Volcanic Complex (Argentina). J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 257, 44–56 (2013).

Tardani, D. et al. Exploring the structural controls on helium, nitrogen and carbon isotope signatures in hydrothermal fluids along an intra-arc fault system. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 184, 193–211 (2016).

Clor, L. E., Fischer, T. P., Hilton, D. R., Sharp, Z. D. & Hartono, U. Volatile and N isotope chemistry of the Molucca Sea collision zone: Tracing source components along the Sangihe Arc, Indonesia. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 6, (3) (2005).

Mitchell, E. C. et al. Nitrogen sources and recycling at subduction zones: Insights from the Izu-Bonin-Mariana arc. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 11, (2) (2010).

Giggenbach, W. F. Variations in the chemical and isotopic composition of fluids discharged from the Taupo Volcanic Zone, New Zealand. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 68(1), 89–116 (1995).

Sano, Y. & Fischer, T. P. The analysis and interpretation of noble gases in modern hydrothermal systems. In: The Noble Gases as Geochemical Tracers. Advances in Isotope Geochemistry (ed Burnard, P.) 249–317 (Springer-Verlag 2013).

Fischer, T. P., Giggenbach, W. F., Sano, Y. & Williams, S. N. Fluxes and sources of volatiles discharged from Kudryavy, a subduction zone volcano, Kurile Islands. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 160, 81–96 (1998).

Fischer, T. P. et al. Temporal variations in fumaroles gas chemistry at Poas volcano, Costa Rica. J. Volcanol. Geotherm. Res. 294, 56–70 (2015).

Peters, K. E., Sweeney, R. E. & Kaplan, I. R. Correlation of carbon and nitrogen stable isotope ratios in sedimentary organic matter. Limnol. Oceanogr 23, 598–604 (1978).

Marty, B. Nitrogen content of the mantle inferred from N2-Ar correlation in oceanic basalts. Nature 377(6547), 326 (1995).

Marty, B. & Zimmermann, L. Volatiles (He, C, N, Ar) in mid-ocean ridge basalts: Assesment of shallow-level fractionation and characterization of source composition. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 63, 3619–3633 (1999).

Kienast, M. Unchanged nitrogen isotopic composition of organic matter in the South China Sea during the last climatic cycle: Global implications. Paleoceanography 15, 244–253 (2000).

Ozima, M. & Podosek, F. A. Noble Gas Geochemistry, 367 pp. (Cambridge Univ. Press 1983).

Lee, H., Sharp, Z. D. & Fischer, T. P. Kinetic nitrogen isotope fractionation between air and dissolved N2 in water: Implications for hydrothermal systems. Geochem. J. 49, 571–573 (2015).

Li, L., Cartigny, P. & Ader, M. Kinetic nitrogen isotope fractionation associated with thermal decomposition of NH3: Experimental results and potential applications to trace the origin of N2 in natural gas and hydrothermal systems. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 73, 6282–6297 (2009).

Sano, Y., Marty, B. & Burnard, P. Noble gases in the atmosphere. In: The Noble Gases as Geochemical Tracers. Advances in Isotope Geochemistry (ed. Burnard, P.) 17–31 (Springer-Verlag 2013).

Sano, Y., Takahata, N. & Seno, T. Geographical distribution of 3He/4He ratios in the Chugoku district, Southwestern Japan. Pure Appl. Geophys. 163, 745–757 (2006).

Matsuda, J. I. & Marty, B. The 40Ar/36Ar ratio of the undepleted mantle; a reevaluation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 22, 1937–1940 (1995).

Hong, W. L. et al. Nitrogen as the carrier gas for helium emission along an active fault in NW Taiwan. Appl. Geochem. 25, 593–601 (2010).

Horiguchi, K. & Matsuda, J. Geographical distribution of 3He/4He ratios in north Kyushu, Japan: Geophysical implications for the occurrence of mantle-derived fluids at deep crustal levels. Chem. Geol. 340, 13–20 (2013).

Matsushita, M. et al. Regional variation of CH4 and N2 production processes in the deep aquifers of an accretionary prism. Microbes Environ. 31(3), 329–338 (2016).

Kerr, A.C., White, R.V., Thompson, P.M., Tarnez, J. & Saunders, A.D. No oceanic plateau-no Caribbean Plate? The seminal role of an oceanic plateau in Caribbean Plate evolution. In: Bartolini, C., Buffler, R.T., Blickwede, J. (Eds.), The Circum-Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean: hydrocarbon habitats, basin formation, and plate tectonics: American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG) Memoir. 79, 126–188 (2003).

Carr, M. J. et al. Element fluxes from the volcanic front of Nicaragua and Costa Rica. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 8 (2007).

Morris, J., Valentine, R. & Harrison, T. 10Be imaging of sediment accretion and subduction along the northeast Japan and Costa Rica convergent margins. Geology 30, 59–62 (2002).

Goss, A. R. & Kay, S. M. Steep REE patterns and enriched Pb isotopes in southern Central American arc magmas: Evidence for forearc subduction erosion? Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 7, (5) (2006).

Gazel, E. et al. Galapagos‐OIB signature in southern Central America: Mantle refertilization by arc-hot spot interaction. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 10, (2) (2009).

Shipley, T. H. & Moore, G. F. Sediment accretion, subduction, and dewatering at the base of the trench slope off Costa Rica: A seismic reflection view of the decollement. J. Geophys. Res. 91, 2019–2028 (1986).

Chen, P., Bina, C. R. & Okal, E. A. (2001) Variations in slab dip along the subducting Nazca Plate, as related to stress patterns and moment release of intermediate-depth seismicity and to surface volcanism. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2, GC000153 (2001).

Busigny, V., Cartigny, P., Philippot, P. & Javoy, M. Nitrogen recycling in subduction zones: A strong geothermal control. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 67(suppl. 1), A51 (2003).

Feigenson, M. D. & Carr, M. J. Positively correlated Nd and Sr isotope ratios of lavas from the Central American volcanic front. Geology 14, 79–82 (1986).

Carr, M. J., Feigenson, M. D. & Bennet, E. A. Incompatible element and isotopic evidence for tectonic control of source mixing and melt extraction along the Central American arc. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 105, 369–380 (1990).

Rupke, L. H., Morgan, J. P., Hort, M. & Connolly, J. A. D. Are the regional variations in Central American arc lavas due to differing basaltic versus peridotitic slab sources of fluids? Geology 30, 1035–1038 (2002).

Morris, J. D., Leeman, W. P. & Tera, F. The subducted component in island arc lavas: constraints from be isotopes B-Be systematics. Nature 344(6261), 31 (1990).

von Huene, R. & Scholl, D. W. Observations at convergent margins concerning sediment subduction, subduction erosion, and the growth of continental crust. Rev. Geophys. 29, 279–316 (1991).

Clift, P. D. et al. Pulsed subduction accretion and tectonic erosion reconstructed since 2.5 Ma from the tephra record offshore Costa Rica. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 6, (9) (2005).

Ranero, C. R. & von Huene, R. Subduction erosion along the Middle America convergent margin. Nature 404, 748–752 (2000).

Ranero, C. R. et al. Hydrogeological system of erosional convergent margins and its influence on tectonics and interplate seismogenesis. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 9, (3) (2008).

Sahling, H. et al. Fluid seepage at the continental margin offshore Costa Rica and southern Nicaragua. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 9, Q05S05, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GC001978 (2008).

Halama, R., Bebout, G. E., John, T. & Scambelluri, M. Nitrogen recycling in subducted mantle rocks and implications for the global nitrogen cycle. Int. J. Earth. Sci. 103, 2081–2099 (2014).

Sinton, C. W., Duncan, R. A. & Denyer, P. Nicoya Peninsula, Costa Rica: A single suite of Caribbean oceanic plateau magmas. J. Geophys. Res. 102, (15507–15520 (1997).

Hauff, F., Hoernle, K., van den Bogaard, P., Alvarado, G. & Garbe‐Schönberg, D. Age and geochemistry of basaltic complexes in western Costa Rica: Contributions to the geotectonic evolution of Central America. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 1, (5) (2000).

Gazel, E., Denyer, P. & Baumgartner, P. O. Magmatic and geotectonic significance of Santa Elena Peninsula, Costa Rica. Geologica Acta 4(1), 193 (2006).

Tryon, M. D., Wheat, C. G. & Hilton, D. R. Fluid sources and pathways of the Costa Rica erosional convergent margin. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 11, (4) (2010).

Widiwijayanti, C. et al. Structure and evolution of the Molucca Sea area: constraints based on interpretation of a combined sea-surface and satellite gravity dataset. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 215, 135–150 (2003).

Plank, T., Ludden, J. N., Escutia, C. & Party, S. S. Leg 185 summary; inputs to the Izu–Mariana subduction system. Ocean Drilling Program Proceedings, Initial Reports, Leg 185, 1–63 (2000).

Marty, B. & Dauphas, N. The nitrogen record of crust–mantle interaction and mantle convection from Archean to present. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 206(3), 397–410 (2003).

Jia, Y., Kerrich, R., Gupta, A. K. & Fyfe, W. S. 15N-enriched Gondwana lamproites, eastern India: crustal N in the mantle source. Earth Plant. Sci. Lett. 215, 43–56 (2003).

Giggenbach,W. F. & Goguel, R. L. Methods for The Collection and Analysis of Geothermal and Volcanic Water and Gas Samples. Tech. Rep. CD 2401 (Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, Institute of Geological and NuclearSciences, New Zealand) (1989).

de Moor, J. M. et al. Gas chemistry and nitrogen isotope compositions of cold mantle gases from Rungwe Volcanic Province, southern Tanzania. Chem. Geol. 339, 30–42 (2013).

Sano, Y., Tokutake, T. & Takahata, N. Accurate measurement of atmospheric helium isotopes. Analytical Sciences 24, 521–525 (2008).

Acknowledgements

This work was sponsored by the National Science Foundation through grant EAR-1049713 (T.P.F.). We acknowledge Maria Martinez and Universidad Nacional de Costa Rica for support. We thank Laura Clor and Carlos Ramirez for help during fieldwork. We also acknowledge Nicu-Viorel Atudorei for help with the stable isotope analyses.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L., T.P.F., and J.M.dM. planned the fieldwork and designed the study. H.L., T.P.F., and J.M.dM. collected the spring samples in Costa Rica. H.L. conducted experiments to obtain results of gas compositions, nitrogen isotope values, and noble gas geochemistry. Z.D.S. supported nitrogen isotope analyses at the Center for Stable Isotopes, University of New Mexico. N.T. and Y.S. supported the noble gas measurements at the Atmosphere and Ocean Research Institute, University of Tokyo. H.L. and T.P.F. collaboratively wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, H., Fischer, T.P., de Moor, J.M. et al. Nitrogen recycling at the Costa Rican subduction zone: The role of incoming plate structure. Sci Rep 7, 13933 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14287-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-14287-y

This article is cited by

-

Mantle degassing along strike-slip faults in the Southeastern Korean Peninsula

Scientific Reports (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.