Abstract

Dissemination of multiresistance has been accelerating among pathogenic bacteria in recent decades. The broad host-range conjugative plasmids of the IncA/C family are effective vehicles of resistance determinants in Gram-negative bacteria. Although more than 150 family members have been sequenced to date, their conjugation system and other functions encoded by the conserved plasmid backbone have been poorly characterized. The key cis-acting locus, the origin of transfer (oriT), has not yet been unambiguously identified. We present evidence that IncA/C plasmids have a single oriT locus immediately upstream of the mobI gene encoding an indispensable transfer factor. The fully active oriT spans ca. 150-bp AT-rich region overlapping the promoters of mobI and contains multiple inverted and direct repeats. Within this region, the core domain of oriT with reduced but detectable transfer activity was confined to a 70-bp segment containing two inverted repeats and one copy of a 14-bp direct repeat. In addition to oriT, a second locus consisting of a 14-bp imperfect inverted repeat was also identified, which mimicked the function of oriT but which was found to be a recombination site. Recombination between two identical copies of these sites is RecA-independent, requires a plasmid-encoded recombinase and resembles the functioning of dimer-resolution systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The discovery and use of antibiotics have helped to save millions of lives in recent decades1. The overuse of antibiotics, however, has contributed to the emergence of new multi-resistant pathogens worldwide, leading to considerable public health problems. Dissemination of antibiotic resistance traits among different bacterial species mainly occurs via conjugation. Thus, understanding this DNA transfer mechanism evokes general interest. The process of conjugation starts with the assembly of a multi-protein complex called the relaxosome around the origin of transfer (oriT), the only DNA sequence required in cis for DNA transfer (for reviews see refs 2,3,4). OriT is often located near genes encoding relaxosome components (e.g., in plasmids RP4, R388, R6K, pCW3, pIP501). In many cases, it contains inverted repeat motifs and AT-rich regions as observed in F5, R6K6, IncPα7, 8, pAD19, pAM3739 or pCW310 plasmids. Conserved sequence motifs have been found in oriTs close to the nic site of several conjugative plasmids such as IncPα plasmids, Ti and Ri plasmids, R64 and pTF-FC211. Relaxase (TraI), the key enzyme of the relaxosome, cuts either strand of oriT DNA at the nic site and covalently binds to the 5′ end of the cleaved strand. The relaxase-DNA complex is subsequently transferred across the membrane-associated DNA transport machinery, the type IV secretion system (T4SS), to the recipient. In addition to TraI, conjugation may require several auxiliary proteins. For example, TraJ of the IncPα plasmid RP4 is indispensable for the initiation of transfer because it binds oriT at a specific site12 and directs the relaxase to the nic site. The complex of oriT DNA, TraJ and TraI is stabilized by TraH through specific protein-protein interactions13. TrwA of the IncW plasmid R388 also binds specifically to oriT and stimulates the ATPase activity of the coupling protein TrwB14, which is required to link the relaxosome complex to T4SS15, 16.

Large single-copy conjugative plasmids of the IncA/C family are often associated with resistance to several antimicrobial agents. Owing to their broad host range, an effective conjugative transfer system and the ability to mobilize multidrug-resistant genomic islands, IncA/C plasmids efficiently distribute multidrug resistance phenotypes among Gram-negative bacteria. Comparative genomic studies have revealed that IncA/C plasmids have a highly conserved backbone that is interrupted by variable antibiotic resistance islands (ARI) at specific positions17. Conjugation, maintenance and replication functions are encoded in the backbone, while mobile genetic elements, such as transposons and integrons, which often carry resistance genes, are localized to ARIs. Similarly to the IncH, J, T and P7 groups of plasmids, as well as the SXT family of integrative conjugative elements (ICEs), the conjugative transfer system of IncA/C plasmids has been classified into the MOBH family18. The transfer genes (relaxosomal and T4SS genes), mostly identified by their homology to characterized tra genes of other systems, are encoded in two clusters. The first region contains genes encoding the putative relaxase (traI), coupling protein (traD), mating pair stabilization protein (traN) and proteins implicated in T4SS assembly (traLEKBVACWU). The second cluster encodes three additional putative proteins involved in T4SS assembly (traFHG)17. Moreover, this region contains two ORFs encoding the FlhDC-family transcriptional activator AcaCD, which activates the expression of transfer genes19 and, therefore, is essential for the conjugation of the IncA/C plasmids. Near the acaCD, another key transfer gene, mobI, has also been identified, although its exact role has not yet been established20. IncA/C-encoded MobI shares 28% identity with MobI protein of SXT/R391 ICEs20, which is indispensable for the transfer of SXT/R391 and is implicated in the recognition of oriT SXT 21.

Biochemical characterization of the relaxase, the MobI or the initiation complex of IncA/C plasmids has not been conducted to date, and the exact position of oriT sequence has not been determined, either. Originally, IncA/C oriT was predicted to be located near traD, however, this annotation was not confirmed experimentally22, 23. Based on the homology of the regions surrounding oriT of SXT/R391 with the corresponding region of the IncA/C plasmid pVCR94, oriT was proposed to be within the intergenic region of vcrx001 (mobI) and vcrx152 20. Although this region was confirmed to carry a functional oriT, two different deletions within the predicted oriT sequence caused only a 10-fold reduction in the transfer frequency, but they did not abolish conjugation. Thus, as a plausible explanation, the presence of a second oriT was suggested. Although most conjugative plasmids possess a single oriT, dual oriT systems have also been reported in the cases of ICEclc of Pseudomonas knackmussi B1324 or plasmids pAD19, 25 and R6K6, which might support the assumption.

Here, we show that IncA/C plasmids have a single oriT locus that is situated closer to the mobI gene than previously predicted20. The ca. 150-bp AT-rich oriT sequence containing multiple short inverted and 14-bp partially overlapping direct repeat motifs covers the promoter region of mobI. The core domain of oriT is confined to a 70-bp segment containing only two inverted repeats (IR) and one copy of the 14-bp direct repeat (DR). We have also identified another locus that appeared to be a second oriT in our experimental setup, but instead was found to be a recombination site consisting of a 14-bp imperfect inverted repeat. Recombination between two identical copies of this putative recombination site, resembling the res sites of several site-specific dimer-resolution systems, is RecA-independent and requires a plasmid-encoded recombinase. Deletion mutants generated in oriT, mobI and the putative relaxase gene caused transfer deficiency, which validated their indispensability for IncA/C conjugation. However, the recombination site did not appear to be involved in transfer. Sequence comparisons indicate that the recombination site is well conserved, suggesting that its intactness is important for IncA/C plasmids in the evolutionary timescale.

Results

Exploration of oriT on IncA/C plasmids

OriT of several conjugative plasmids was found adjacent to genes encoding relaxosome components and oriT of IncA/C plasmids was also predicted to be near traI. To prove this assumption, traI of R16a and IP40a was knocked out using the one-step gene inactivation method26. These IncA/C plasmids were chosen because they have few resistance markers27, which makes it easier to apply this KO technique. Due to the lack of sequence information at that time, KO experiments were designed according to the sequence of R55, which has been previously published28 and reported to be a close relative of R16a and IP40a27. The traI KO mutants, as expected, could not conjugate, confirming that this gene is indispensable for IncA/C transfer. The CmR marker replacing traI in the KO mutants enabled us to clone the region surrounding traI. Accordingly, the HpaI fragment of R16a ΔtraI::cat mutant containing >4.2 kb flanking regions of both sides of traI was inserted into a non-mobilizable pACYC177-derivative29 vector, pJKI708. Transfer of the resulting plasmid, pJKI854, was tested using E. coli donor strain TG1Nal/R16a. While conjugation of R16a into TcR recipient E. coli strain TG2 occurred with a frequency of 3.5 ± 1.2 × 10−4, transfer of pJKI854 was undetectable (<1.1 ± 0.9 × 10−7), indicating that functional oriT was missing not only in the region between traD and traJ, as shown previously20, but also in the ca. 11.6-kb region of the 12 ORFs including a topoisomerase III gene, traI, traD, the conjugative transfer protein genes 234 and s043(traJ), as well as several other hypothetical genes.

To identify oriT, nine different libraries were constructed from R55 in vector pJKI708 and introduced into E. coli strain TG2/R55. The recA strain was applied to reduce homologous recombination between R55 and the cloned R55 fragments. Using these transformant cell populations as donors in crosses with the TG1Nal recipient strain, transconjugants were obtained from three libraries. In the case of libraries L1, L2 and L5, the frequency of transconjugants was 4.2 × 10−9, 1.9 × 10−9 and 2.0 × 10−6, respectively. Extensive restriction analysis of the transferred plasmid species revealed two different mobilizable regions (Mob 1 and 2) in R55. Among the transferred clones obtained from L2, the shortest insert (2.72 kb) proved to be part of all the longer clones from L1 and L2 and spanned the ORFs from R55_176 to the upstream intergenic region of R55_180 and the 5′ portion of ORF R55_1 (pJKI964, Fig. 1a). By contrast, two different mob regions were found in the L5 library. One of these clones, named pJKI963, contained a 2.83-kb fragment that partially overlapped the insert of pJKI964 and contained ORFs from R55_180 up to the 5′ part of R55_3 (repA). The overlapping part of these clones was named the Mob 1 region (pJKI967). These results were consistent with that the oriT of another IncA/C plasmid, pVCR94, has previously been localized in this region20. The other mobilized clone from L5, pJKI962, contained a 0.75-kb SacI fragment named Mob 2, which contained the intergenic region flanked by the truncated ORFs R55_128 and R55_196 (Fig. 1c).

Identification of mobilizable fragments of R55. Subclones of two Mob regions were constructed in the p15A-based vector pJKI708, and their conjugation frequency was measured in the presence of R55 using the recA E. coli strain TG2. pJKI708 (without insert) was used as a negative control. The schematic maps representing the regions of R55 covered by the subclones listed below are drawn to scale, and the coordinates are shown according to the published R55 sequence. Open arrows indicate the annotated ORFs. Stretches with coordinates represent the fragments carried by the p15A-based plasmids. Asterisks indicate that the transfer frequency was below the detection limit (<10−8). (a) Conjugation frequency of different subclones of Mob 1 region. The grey box shows the oriT region. (b) Detailed map of the oriT region. Color-coded arrows represent inversely (IR) and directly (DR) repeated sequence motifs of at least 4 bp in length (IR1: 6 bp with 1 mismatch, IR2: 4 bp, IR3: 5 bp, IR4: 6 bp, IR5: 6 bp and IR6: 7 bp with 1 mismatch). Asterisks in IR1 and IR6 refer to the imperfect repeat. The red region in IR4 and IR5 represents the 4-bp IR2 motif as a part of these repeats. The region deleted from R16a and IP40a (resulting in the ΔoriT mutants) and the p15A-based subclones of R55 oriT region are shown below the graph. The potential secondary structure of the region is also shown. Coordinates corresponding to the endpoints of cloned fragments and the repeated motifs are indicated. The red arrows point to the base positions where IncA/C family plasmids most frequently carry divergent bases (see also Supplementary Fig. 6). (c) Transfer frequency of subclones of the Mob 2 region. The 11-bp IR1 and 14-bp IR2 inverse repeat motifs are shown as light green arrows. Vertical arrows indicate the positions of ARIR16a and Tn6333 insertions in the related R16a and IP40a plasmids.

The identification of minimal functional oriTs in the Mob 1 and the Mob 2 regions was based on the mobilization assays for the three original clones and their gradually shortened derivatives created by repeated subcloning (Fig. 1). All but one plasmid carrying the Mob 1 fragment comprising the 139–323 bp region of R55 showed a maximal transfer rate. The only exception, pJKI964, contained the H-NS-like protein gene acr2, which was identified as a repressor of acaCD, encoding the master activator of tra genes19. The lower conjugation frequency of pJKI964 (and also that of the R55 helper plasmid, data not shown) can be explained by the elevated Acr2 level produced by the 15–20 copies of the p15A-based pJKI964 in the donor cells. All these data suggested that the fully functional minimal oriT sequence in the Mob 1 region was located between the 139–323 bp positions within the intergenic region of the divergent ORFs R55_180 and R55_1 (mobI) (corresponding to the overlapping region of pJKI974 and pJKI986). Testing the Mob 2 region by a similar method indicated that the putative second oriT is situated in a short fragment (119169–119224 bp) surrounded by the divergent ORFs R55_128 and R55_196 (pJKI1053).

Identification and characterization of oriT in the Mob 1 region

Sequence analysis of the Mob 1 region revealed a complex array of short inverted and direct repeats (IRs and DRs, respectively). For a more exact localization of the functional oriT sequence, the Mob 1 region of R55 was further shortened by deleting the repetitive motifs (Fig. 1a,b). The transfer frequencies of these subclones showed that the absence of the 97–139 bp segment (pJKI986/974) had no effect, while the lack of the sequence containing IR1 and IR2 (pJKI1000/1001) slightly reduced the mean transfer rate values. By contrast, the deletion of the overlapping 14-bp DRs located within the 280–323 bp segment (pJKI987) completely abolished the transfer, although the deletion of a single copy of this DR had only a weak impact (pJKI1002). The deletion of the 208–227 bp segment, including IR1, IR2 and one copy of IR3 (pJKI1008), or the simultaneous removal of the 97–208 bp and 300–323 bp regions (pJKI1006), significantly reduced the transfer frequency. The shortest fragment that had only the IR4, IR5 and one copy of the 14-bp DR (pJKI1007) showed a similarly low, but still detectable, transfer rate. These data again confirmed that the fully functional oriT was located between the 139–323 bp segment of R55, while a minimal functional oriT was found within the 227–300 bp region; however, this sequence already lacks several important sequence motifs.

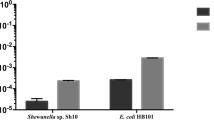

To further analyze the function of this region, we created deletion mutants of our IncA/C plasmids. R55 was not the best candidate for gene KO due to its multiple resistance genes, therefore R16a and IP40a were used instead. To verify that the oriT region was similar or identical in all three plasmids, the mobI genes and the segments corresponding to 97–399 bp of the Mob 1 region in R55 were amplified and sequenced from R16a and IP40a. The mobI genes of the three plasmids and the oriT region of R55 and IP40a were identical, while the only sequence divergence in the oriT region of R16a was the presence of an additional copy of the 14-bp DR. After cloning this divergent oriT fragment, its conjugation was compared to that of the analogous R55 fragment from donor strains containing either R55 or R16a helper plasmids (Supplementary Table 1). The results indicated that both fragments were similarly mobilized by both helpers, which confirmed the equivalence of these sequence variants and that the planned KO mutations in R16a and IP40a would provide general information regarding the function of this region. Consequently, the mobI gene and its 126-bp upstream region were independently deleted in R16a and IP40a by the one-step gene KO method. Surprisingly, both mutations resulted in the cessation of conjugation as the transfer frequencies of the ΔoriT and ΔmobI mutants of both plasmids were below the detection limit (<6.9 ± 5.2 × 10−8), while those of wt R16a and IP40a were 7.6 ± 4.8 × 10−3 and 1.0 ± 0.7 × 10−4, respectively. The complete termination of transfer by the deletion of either oriT or mobI indicated that the intact Mob 2 region could not complement the deleterious effects of these KO mutations in the Mob 1 region.

As oriT in the Mob 1 region is located immediately upstream of the mobI gene, which is essential for conjugation20, we supposed that the oriT deletion knocked down mobI expression by removing its promoter. To test this hypothesis, complementation of the KO mutant IncA/C plasmids was carried out using three p15A-based plasmids containing the Mob 1 region with or without an intact mobI gene (pJKI1011 and pJKI969, respectively) and an expression vector, pJKI1021, carrying mobI under the control of the P tac promoter without the oriT region (Fig. 2a). Plasmids pJKI1011 (oriT +, mobI +) and pJKI1021 (oriT −, mobI +) expressing mobI in trans restored the transfer of the ΔmobI R16a mutant, and pJKI1011 could also be transferred, as expected. However, none of the plasmids could complement the ΔoriT R16a mutant, indicating that the deletion inactivated the oriT sequence itself and that the transfer deficiency in this case was not due to the lack of MobI protein (Fig. 2b). Similar results were obtained for IP40a (data not shown), but all transfer frequencies were ca. two orders of magnitude lower, as also observed for the wt plasmid. The vast majority of the few R16a ΔoriT transconjugants, with a frequency near the detection limit (ca. 5.0 × 10−7), also contained pJKI1011, which suggested that R16a transfer occurred via R16a::pJKI1011 cointegrates formed possibly via homologous recombination. In these cointegrates both oriT and MobI could be provided by pJKI1011. By contrast, transconjugants were not obtained in the presence of pJKI969 (oriT +, mobI −) despite the similar possibility of plasmid cointegrate formation. The complete lack of transfer of both the oriT + plasmid pJKI969 and the ΔoriT R16a helper clearly supported the conclusion that the deletion of oriT also prevented mobI expression. The results also strengthened the previous observation that the intact Mob 2 region could not complement the ΔoriT mutation even in the presence of MobI. All these findings confirmed that IncA/C plasmids have a single oriT that is located in the Mob 1 region immediately upstream of the mobI gene.

Complementation of deletion mutants in the Mob 1 region. (a) Schematic map of deletion mutants generated in the Mob 1 region of R16a (thick line) and the regions cloned from R55 into a p15A-based non-mobile vector (thin arrows) that were applied in complementation tests. Open boxes represent the deleted regions in R16a (the same deletions were also created in IP40a), and other symbols are as described in Fig. 1.(b) Conjugation assays were performed to demonstrate the trans-mobilization effect of the different fragments of the R55 Mob 1 region on the transfer-defective R16a deletion mutants. The bars show the mean transfer frequencies of the ΔoriT and ΔmobI R16a mutants and the complementing p15A-based plasmids when present together in the donor TG1Nal E. coli cells. ‘*’Indicates that the transfer frequency was below the detection limit (<10−8). ‘**’Indicates a very low transfer frequency of ΔoriT R16a when the complementing plasmid carried oriT+mobI. In this case, co-transfer of the two plasmids was >67%.

The promoter region of mobI overlaps oriT

The non-coding region between the divergent genes R55_180 and mobI was inserted into a β-galactosidase tester plasmid to measure the promoter activity that drives mobI expression. In the resulting plasmid pMSZ952, the upstream region of mobI was fused to the promoterless lacZ gene. The original GTG start codon of mobI was replaced with ATG of lacZ. The β-gal assay showed that this region contains a relatively strong promoter as pMSZ952 produced 2462±55 U of β-galactosidase, while the empty vector pJKI990 used as a negative control produced 1.0±0.5 U. For further specification of this promoter, the transcription start site (TSS) of mobI was determined in a primer extension experiment (Fig. 3). Based on the strongest signal, the TSS was located 93 bp upstream of the GTG start codon, however, several weaker signals were also obtained compared to the negative control. The promoter identified by the primary TSS has a TTGACA −35 box corresponding with the σ70 consensus and a less obvious −10 box. All secondary TSSs were closer to the start codon, and the respective promoter-like sequences appeared to be more divergent from the consensus. Our results, however, indicated that all possible promoters of mobI were located in the core region of oriT.

Determination of mobI TSS. The primer extension reaction was performed using total RNA purified from E. coli TG1 cells carrying the P mobI ::lacZ fusion plasmid pMSZ952 (+) or pJKI990 as a negative control (−). Primer pUCfor21 annealing near the start codon of lacZ was used for extension reactions and sequencing. Lanes G, A, T, C: Sanger sequencing reactions obtained with pMSZ952 template DNA. Arrowheads denote the bases corresponding to the TSSs on the non-transcribed strand. The arrows with R55 coordinates above the sequence of the sense strand show the detected TSSs. The start codon and the deduced Shine-Dalgarno, −10 and −35 boxes in the P mobI region are indicated below the sequence. The line styles of the arrows and underlining of the promoter boxes indicate the respective TSS, −10 and −35 box. The deleted region in the ΔmobI R16a and IP40a mutants is highlighted in grey. The full-length gel is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1.

MobI protein is a plasmid-specific transfer factor

MobI has been shown to be indispensable for IncA/C conjugation, although its exact function is not yet clear. As IncA/C plasmids are the exclusive and efficient conjugation helpers of the multiresistant mobilizable integrative elements such as Salmonella Genomic Island 1 (SGI1) and its variants, we tested whether MobI was involved in SGI1 transfer. The R16a ΔmobI mutant was applied in a SGI1 mobilization assay from E. coli strain TG1Nal::SGI1-C, which showed that the conjugation-deficient ΔmobI plasmid could mobilize SGI1 more efficiently than wt R16a (Table 1). The higher rate of SGI1 transfer observed in the case of the ΔmobI helper plasmid may be explained by the lack of competition between SGI1 and the helper for components of the transfer apparatus as the mutant plasmid is unable to conjugate probably due to an error in the initiation. This result clearly indicated that MobI is a plasmid-specific factor that is not required for SGI1 transfer.

The Mob 2 region contains a recombination hot spot rather than a second oriT

The first suggestion that the Mob 2 region may not contain a real oriT derived from the analysis of KO mutants of the Mob 1 region. If a second, active oriT was present in the Mob 2 region, the elimination of oriT in Mob 1 should not have abrogated the plasmid transfer. By contrast, the deletion of oriT in Mob 1 was deleterious for conjugation even in the presence of MobI expressed in trans, indicating that the Mob 2 region could not complement the absence of the transfer functions of Mob 1. Further support for this idea was derived from an experiment in which the mobilization of the “oriT2” sequence was investigated in the presence of wt or the ΔoriT mutant R16a. As ΔoriT deletion eliminates mobI expression, which might also be required for “oriT2” mobilization (it was not clear at this stage), the “oriT2” sequence was inserted into a mobI expression vector supplying MobI protein. The resulting plasmid, pJKI1045, was mobilized by wt R16a at a frequency of 2.7 ± 1.7 × 10−6, while its mobilization by ΔoriT R16a was undetectable (<2.8 ± 1.0 × 10−8), suggesting that the transfer of “oriT2” depends on the conjugation of the helper plasmid but not directly on the presence of MobI.

The analyses of Mob 2 deletion mutants further strengthened our suspicion. The sequence in the Mob 2 region, which behaved like oriT when inserted into the p15A plasmid (provisionally called “oriT2”), was localized between the conserved divergent ORFs R55_128 and R55_196 with unknown functions (Fig. 1c). Before the generation of deletion mutations, the sequences of the homologous regions in R55, R16a and IP40a were compared, which revealed large interrupting insertions in this region in R16a and IP40a30. Both insertions (the 30-kb ARIR16a and the 11.5-kb Tn6333) separated the “oriT2” sequence from the homologs of ORF R55_196 without an apparent deleterious effect on the transfer of R16a and IP40a. Thus, based on the observation that the genetic context of “oriT2” and R55_196 is not conserved in the three plasmids, we supposed that R55_128 might be the corresponding accessory gene for the presumptive “oriT2” (as is mobI for oriT in the Mob 1 region) rather than R55_196. Deletions of the “oriT2” sequence or the homologs of ORF R55_128 were generated in R16a and IP40a, and the mutants were tested for their conjugation activity. None of the deletions had a detectable effect (Supplementary Fig. 2), further supporting that this region does not carry oriT despite the previous observation that the sequence designated as “oriT2” could somehow be transferred if it was cloned into a non-mobilizable vector (Fig. 1c).

When comparing the incidence of co-transfer of the helper plasmid R55 and the p15A-based subclones of the Mob 1 and Mob 2 regions, a striking difference was observed. While the frequency of transconjugants that received R55 along with Mob 1 (oriT)-containing plasmids (pJKI1001, pJKI1006, pJKI1007 and pJKI1008) ranged between 25% and 61%, the Mob 2 (“oriT2”)-containing plasmids (pJKI972, pJKI984 or pJKI998) showed a prevalence of similar double transconjugants ranging from 99–100%. The same phenomenon was observed for pJKI1045 (oriT2+, mobI +) transferred by wt R16a. This rate of co-transfer was unexpectedly high assuming the independent transfer of the helper and the tested plasmids. This result raised the possibility that the high frequency was due to cointegrate formation even in the recA − background of TG2 donor cells via homology-dependent recombination between the Mob 2 sequences present in both the helper and the Mob2-bearing plasmids. To test this hypothesis, PCRs amplifying the expected junctions of such cointegrates were performed using the transconjugant colonies bearing pJKI972 and pJKI998. However, no junction fragments could be amplified despite the presence of both R55 and p15A plasmids in the transconjugants.

Based on this negative result, we supposed that the transconjugant cells that had acquired a cointegrate of the 10–15-copy-number p15A plasmid and that the 170-kb IncA/C plasmid were not viable unless the cointegrate was resolved. Theoretically, such cells should have replicated the cointegrate until its copy number reached the standard copy number of the p15A replicon, which would mean the synthesis of ca. 2.3 Mb extra DNA (half of the chromosomal DNA) in each cell cycle. Therefore, it is more probable that those transconjugant cells formed colonies that escaped this load by resolving these “high copy” cointegrates. Thus, we expected the cointegrates to be more stable if their copy number did not exceed 1–2 per cell. To verify this hypothesis, the 350-bp and the shortest, 56-bp, transferable fragment of the Mob 2 region (corresponding to the inserts of pJKI972 and pJKI1053, respectively) were cloned into the single copy F plasmid derivative pBeloBac11. The resulting plasmids, pJKI1051 and pJKI1056, were introduced into TG1Nal/R16a and TG1Nal/R16a Δ“oriT2” cells, and their transfer frequency was measured using the F′-cured TG90 strain as a recipient. When wt R16a was applied as a helper, the transfer efficiency of both plasmids was ca. 1/10 that of the helper plasmid (Fig. 4a), independently of the length of the Mob 2 region present in the single copy vector as was observed previously for a series of p15A-based Mob 2 bearing plasmids (Fig. 1c). The resistance phenotype tested for >60 transconjugant colonies from four parallel experiments revealed a co-transfer rate of Bac-based pJKI1051 and pJKI1056 with R16a of 100%. Contrarily, no transconjugants were obtained with the R16a Δ“oriT2” helper, even though its transfer frequency was similar to that of wt R16a. Similar results were obtained when the recA − TG2 strain was used as the recipient strain in the same experimental setup, except that significantly lower transfer frequencies were detected for the Bac-based plasmids probably due to the presence of the incompatible F′ plasmid in the recipient strain (Supplementary Fig. 3). Colony PCR designed to detect the expected junctions of R16a::pJKI1056 cointegrates (Fig. 4b,c) confirmed that all the tested transconjugant colonies contained both the cointegrate and its resolution derivatives, free pJKI1056 and R16a. This result verified that the single-copy cointegrate was sufficiently stable to be maintained until the transconjugant cells formed colonies, but the reversed recombination process resolved the cointegrates at a detectable rate. The above results clearly indicate that the “oriT2” sequence is not a real oriT but contains a highly recombinogenic sequence renamed as RecHS (“Recombination Hot Spot”).

Transfer of RecHS-bearing plasmids through cointegrate formation with R16a helper plasmid. (a)The transfer frequency of pJKI1051 and pJKI1056 in the presence of the wt and the “ΔoriT2” R16a helper plasmids. The donor strain TG1Nal contained the helper plasmid along with the Bac-based RecHS-bearing plasmids pJKI1051 or pJKI1056. E. coli TG90F− was used as the recipient strain. Asterisks indicate that transfer of pBeloBac11 vector by the wt R16a and the RecHS-bearing plasmids by the “ΔoriT2” R16a helper plasmid was undetectable (<3.0 × 10−8). (b) The schematic graph shows pJKI1056 (thick line), the wt R16a (thin line) and the expected cointegrate formed by recombination via the RecHS copies. ARIR16a refers to the antibiotic resistance island in R16a inserted downstream of RecHS, orf128 denotes the homolog of ORF R55_128 located upstream of RecHS and CmR indicates the position of the resistance gene in pJKI1056. Primers used for detection of the left (LJ) and right (RJ) junctions of R16a::pJKI1056 cointegrate and the free pJKI1056 and R16a plasmids are indicated. (c) Detection of the R16a::pJKI1056 cointegrate and the free parental plasmids by colony PCR in six independent transconjugant colonies obtained using TG90F− (lanes 1–6) and recA − TG2 (lanes 8–13) recipients. To eliminate donor contamination, the transconjugant colonies were streaked onto LB + Tc + Km + Cm agar plates, and single colonies were selected as templates in the PCR tests. The primer pairs used and the length of the resulting amplicons were as follows: c–b for LJ (513 bp), a–d for RJ (516 bp), a-b for pJKI1056 (515 bp) and c,d for R16a (499 bp) (a, cat3; b, pUCfor21; c, R55_T1for; d, IP40/R16_T1rev). Mw: 100-bp ladder (Invitrogen). The full-length gel is presented in Supplementary Fig. 4.

RecHS is conserved in the IncA/C family and recognized by a plasmid-encoded recombinase

A comparison of the transferable and non-transferable fragments of the Mob 2 region indicated that the recombination activity depends on the intactness of the 14-bp imperfect inverse repeat (IR2) with 6-bp spacing (compare pJKI1053 and pJKI1054, Fig. 1c), while the 13-bp perfect inverse repeat with 1-bp spacing (IR1) located 27 bp upstream of IR2 seems dispensable for the recombination (compare pJKI998, pJKI999 and pJKI1053, Fig. 1c). The RecHS sequence was well conserved among the >150 sequenced IncA/C plasmids. Apart from the 14 family members that were missing this region, only XNC1_p and XNC2 carried a single A→G change in the right arm of IR2 (IR2R), and 28 of 138 members contained 1 or 3 divergent bases in the spacer region (Supplementary Fig. 5).

The previous results ruled out the involvement of RecA in RecHS-recombination, and thus we were interested in whether the IncA/C plasmid or the host cell encode the cognate recombinase. The compatible plasmids pJKI1053 (p15A) and pJKI1056 (Bac) carrying the same RecHS sequence were introduced into TG2 and TG2/R16a Δ“oriT2” cells (R16a Δ“oriT2” lacks RecHS and was used to avoid recombination of the test plasmids with the IncA/C plasmid), and the transformant colonies were tested by PCR for the presence of pJKI1053::pJKI1056 cointegrates. Based on the detection of cointegrates only in the presence of R16a Δ“oriT2” (Fig. 5) it was confirmed that the IncA/C plasmid itself encodes the cognate recombinase.

Detection of the cognate recombinase of RecHS. (a) The graph shows the Bac- (thick line) and p15A-based (thin line) RecHS-bearing plasmids and the expected cointegrate formed by recombination via RecHS copies. (b) Colony PCR was conducted for six independent transformant E. coli TG2 colonies carrying pJKI1053 and pJKI1056 with or without “ΔoriT2” R16a (the deletion mutant R16a lacking RecHS was used to avoid recombination with the other two plasmids). The left and right junctions of the pJKI1053::pJKI1056 cointegrates (LJ and RJ, respectively) could be amplified only in the presence of R16a as a 482-bp and a 257-bp fragment. The primers used were c–b for LJ and a–d for RJ (a, cat3; b, pUCfor21; c, pBRBgl; d, pBRPst). Mw1, lambda DNA digested with PstI; Mw2, 100-bp ladder (Fermentas); ntc, nontemplate control.

Discussion

IncA/C plasmids are of great importance due to their efficiency in the spread of multiresistance in Enterobacteriaceae and several other families of γ-Proteobacteria. Although the first IncA/C family plasmids were identified in the late 1960s31, 32, details of their basic biology have been studied only recently. Most genes of their conjugative transfer system have been identified based on their homology to other genes with known functions. Genetic analyses have been reported on the regulation of tra genes19 and on the genetic background of crosstalk between IncA/C plasmids and SGI1 genomic islands mobilized exclusively by these plasmids19, 33, 34, 35. Although most genes of the transfer apparatus have been identified, the cis-acting element of transfer initiation, the oriT region, has not yet been unambiguously defined. OriT was first localized between traD and traJ 23; however, this location was later disproved, and an oriT region was identified in the noncoding region upstream of mobI. Deletions generated in the predicted oriT sequence caused a ca. one order of magnitude drop in transfer frequency, but plasmid transfer was not abolished, which led to the suggestion that a second oriT may exist20.

Here, we report the more precise localization of the IncA/C oriT sequence and exclude the possibility of a second one. However, we identified a second region that could mimic the function of oriT in the experimental setup applied for the isolation of oriT. Using R55 fragment libraries, we identified two distinct regions of R55, Mob 1 and Mob 2, that rendered the non-mobile p15A plasmid mobilizable by an intact R55 helper plasmid, thus appearing to carry an oriT. In a similar test, the presence of an oriT in the ca. 11.6-kb surroundings of the relaxase gene, traI, was excluded.

Mob 1 of R55 was shown to be homologous to the region in which oriT of another IncA/C plasmid, pVCR94, was recognized20. Based on the transfer frequencies of the sequentially shortened subclones of the Mob 1 region, oriT was identified in the 139–323 bp region of R55 immediately preceding the mobI gene (Fig. 1a,b). Unlike the previously reported ΔoriT1_94 and ΔoriT2_94 deletions (corresponding to 39–203 bp and 170671–203 bp segments of R55, respectively)20 in pVCR94ΔX, the ΔoriT deletions removing the 129-bp and 115-bp stretches upstream of the mobI gene in the related IncA/C plasmids R16a and IP40a completely abolished plasmid transfer and confirmed that the most important parts of oriT are immediately adjacent to mobI.

Sequence analysis of the 139–323 bp region revealed a strong bias in GC content. In contrast to the 53% GC of the whole R55 and 51% of its conserved backbone sequence (excluding ARI-B and ARIR55/Tn6187 30), oriT was found to contain only 37% GC. Furthermore, a complex array of short perfect and imperfect inverted and direct repeats (Fig. 1b) could be found, as is also characteristic of several other oriT loci5, 6, 8, 9, 10. Further shortening of the 139–323 bp region had a negative effect on the transfer rates. Removal of the upstream segment, including IR1 and IR2, caused a minor reduction, indicating that this region contained sequences with some non-essential roles in the transfer. This result is supported by the ca. ten-fold decrease in the transfer rate observed with ΔoriT1_94 and ΔoriT2_94 deletion mutants of pVCR94ΔX20, both of which removed distal parts of upstream sequences of oriT, including IR1 and IR2. Because the absence of the 97–139 bp region had no detectable impact on the transfer rate (compare pJKI974 and pJKI985 in Fig. 1a,b), in this side of oriT, the effective sequence(s) must be located between 139–208 bp, near or even overlapping the IR1 or IR2 motifs. Sequential shortening of the oriT region from the other side (adjacent to mobI) exhibited a gradual effect. Deletion of the 323–353 bp region with IR6 had no impact, while removal of one copy of the overlapping 14-bp DRs caused a slight decrease in the transfer rate. However, the removal of both DRs, which also destroys IR5, eliminated the transfer, suggesting that this region encompassed the most important elements of oriT (such as the nic-site and indispensable binding sites). Interestingly, simultaneous deletion of the IR1/IR2 region and the 14-bp DR2 (pJKI1006) had a cumulative effect as it led to a 2 log drop in transfer frequency, similar to the deletion of the region from IR1 to IR3 (pJKI1008). Thus, we concluded that the core of oriT is located in the 227–300 bp fragment (pJKI1007), including IR4, IR5 and at least one copy of the 14-bp DR, but the fully functional oriT is covered by the 139–323 bp region.

The comparative analysis of sequences homologous to the oriT region of R55 also supports this conclusion. To date, more than 150 sequenced IncA/C family members can be found in public databases (Supplementary Table 2). Even though 5 of 152 plasmids lack oriT due to large deletions spanning the whole Mob 1 region, including the mobI gene, this region is highly conserved. Fifty-seven of the remaining 147 plasmids show some sequence divergence in comparison to R55, while 89 are identical to it (Supplementary Fig. 6). The oriT locus of the six most divergent plasmids begins at the 169/170 bp position of R55. This group includes two plasmids that have been reported to undergo conjugal transfer: pRA136, 23, the only sequenced IncA/C1 plasmid, and pKHM-137, which cannot be unambiguously classified into Type 1 or Type 2 clusters of the IncA/C2 lineage30. The self-transfer capability of these plasmids confirms again that the missing region, including IR1, is not necessary. In the 170–323 bp region of R55, there are three positions in which the other plasmids contain divergent bases; however, these positions occur in the spacing of IRs (Supplementary Fig. 6, Fig. 1b). The only striking variance in the core oriT region can be seen in R16a, where three rather than two copies of the overlapping 14-bp DRs were found30. Comparison of the trans mobilization of R16a and R55 Mob 1 regions by both plasmids showed that this additional repeat had no significant effect. Based on this compilation of sequences, oriT of the IncA/C plasmids could be determined as the 170–323 bp of R55 containing IRs from IR2 to IR5 and the 14-bp DRs; however, the functions of these repeats remain to be established. Although there have been many efforts to identify the nic site in oriT, both biochemical (primer extension) and in vivo (interrupted mating) approaches have failed to provide positive results, and thus further in vitro assays performed with purified proteins might help to solve this problem.

The oriT is located immediately upstream of mobI, a highly conserved gene (Supplementary Table 2) that is necessary for plasmid transfer20. MobI was identified due to its analogous genetic context to mobI of SXT21, although its function has not yet been determined. Swiss-Model and Phyre2 modeling of the MobI protein structure have predicted some homology in the C terminus with the DNA-binding domain of the EIN3 transcription factor of Arabidopsis thaliana, raising the possibility that MobI has DNA binding activity and might have similar functions in transfer to oriT-binding auxiliary proteins as TraJ of RP412, TraY of F factor38, TrwA of R38814 or MobC of RA339. Although the exact function and mode of action of MobI are not yet clear, we demonstrated that it is a plasmid-specific transfer factor that is not required for the trans mobilization of SGI1.

β-galactosidase assay showed that the upstream region of mobI contained a relatively strong promoter, which was identified by a primer extension experiment. The most abundant transcript started at the 229 bp position of R55 which defined a promoter with a −35 box (TTGACA) that aligned perfectly with the consensus σ70 promoter box followed by a less ideal −10 box (TAGCCT) with 16-bp spacing. Interestingly, four additional secondary TSSs were also detected closer to the start codon (Fig. 3). All the TSSs and the corresponding promoters were located in the most important part of oriT. Similar overlap between oriT and the promoter of adjacent genes has been found in several plasmids from other families such as RP47, R10040, RA339, pMV15841 and pIP50142. This context in IncA/C oriT raises the possibility of crosstalk between mobI transcription initiation and the formation of the initiation complex of conjugal transfer. Furthermore, binding of MobI to oriT might lead to the autoregulation of mobI transcription.

The method by which the Mob 1 region including oriT was entrapped provided a second region, Mob 2, that also appeared to be mobilizable. Further analyses, however, ruled out the possibility that Mob 2 carried a second oriT. Conjugation tests for the gradually shortened Mob 2 region fragments inserted into a p15A-based vector led to the identification of a 56-bp region, RecHS, that appeared to be fully active in the transfer by a helper plasmid, but the deletion of this region from R16a or IP40a had no impact on their conjugation frequencies. By contrast, the deletion of oriT in the Mob 1 region abolished conjugation, which excluded the presence of a second oriT either in Mob 2 or in any other regions of the plasmids. The nearly 100% co-transfer of Mob 2 bearing p15A- or Bac-based plasmids with the helper plasmid and the complete termination of their transfer when the helper was unable to conjugate (ΔoriT) or lacked the RecHS (Δ“oriT2”) indicated that transfer of the Mob 2 region undoubtedly occurred via cointegrate formation with the helper plasmid. We have shown that cointegrates are formed via a RecA-independent recombination that occurs between two RecHS sequences. The presence of the IncA/C plasmid is necessary for the recombination, indicating that the plasmid itself encodes the cognate recombinase. It was also shown that this enzyme is able to carry out the recombination process in both directions i.e. the formation or the resolution of cointegrates.

The RecHS region contains a 14-bp imperfect inverted repeat with 6-bp spacing (IR2). Neither the Mob 2 fragments lacking IR2 (pJKI965, Fig. 1c) nor those carrying only one copy of the IRs (pJKI997, pJKI999 and pJKI1054, Fig. 1c) could be transferred, implying a key role for this motif in recombination-dependent cointegrate formation. The structure of IR2 clearly resembles the recombination sites of several site-specific recombination systems that are involved in the dimer resolution of plasmids, such as rfsF of F factor43, FRT of 2 μm plasmid44 of yeast or loxP of P1 phage45. All these sites consist of 10–14-bp imperfect inverted repeats with a central 6–8-bp spacer in which strand cleavage and rejoining are carried out by the cognate recombinases. The chromosomal and several plasmid-borne dimer resolution systems (XerCD-dif/cer) have similar functions, but their recombination sites, dif and cer, are not composed of inverted repeats46. The res loci of another group of cointegrate resolution systems occurring in Tn3-family replicative transposons also contain inverse repeats with 2–7-bp spacers, although res sites generally consist of three similar copies of IRs (resI, II and III) with different spacing lengths between the repeated motifs47. Although the cognate recombinase of RecHS has not yet been identified, we believe that IR2 in the RecHS sequence acts as a recombination site in a site-specific system similar to the rfsF-D protein system of F plasmid48. High conservation of the RecHS sequence in the IncA/C family (Supplementary Fig. 5) suggests that it has an important function. Based on the analogy to several dimer resolution systems, RecHS might have a role in plasmid stability. However, 14 of 152 IncA/C plasmids lack the RecHS region (Supplementary Table 2), indicating that this system is not necessary for stable maintenance, presumably due to other stabilizing functions. The detailed analysis of this recombination system is currently underway.

Methods

DNA and microbial techniques

Relevant features of the bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 2. The detailed methodology of the plasmid constructions is described in Supplementary Methods. Standard molecular biology procedures were carried out according to49. Test PCRs were performed as previously described50 using Dream Taq polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific). All cloned amplicons were amplified with Phusion polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and sequenced on an ABI Prism 3100 Genetic Analyzer (Perkin Elmer) after cloning. Oligonucleotide primers are listed in Supplementary Table 3. Primers for gene KOs were designed according to the published sequences of R55 (GenBank: JQ010984), R16a (GenBank: KX156773) and IP40a (GenBank: KX156772). Bacterial strains were routinely grown at 37 °C in LB supplemented with the appropriate antibiotics used at a final concentration as follows: ampicillin (Ap) 150 μg/ml, chloramphenicol (Cm) 20 μg/ml, kanamycin (Km) 30 μg/ml, spectinomycin (Sp) 50 μg/ml, streptomycin (Sm) 50 μg/ml, nalidixic acid (Nal) 20 μg/ml, gentamicin (Gm) 25 μg/ml, tetracycline (Tc) 10 μg/ml. For maintaining and curing the plasmids with the temperature-sensitive pSC101 replication system, 30 and 42 °C incubation temperatures were applied, respectively. Standard conjugation assays were carried out in 4–6 replicates and 2–6 independent experiments as previously described50. The transfer frequencies are given as the ratio of transconjugant and recipient titers, if other is not indicated. The β-galactosidase assay was performed in 4 replicates according to51 except that the cultures were grown in LB at 37 °C to an OD600 ~0.3 and diluted in at a 1:9 ratio with Z buffer.

Isolation of the Mob regions of R55

R55 libraries L1-L9 were generated by digestion of ca. 200 ng of R55 plasmid DNA purified with the Qiagen Plasmid Maxi kit. Plasmid DNA was cut with BamHI-BglII (L1); BstYI (L2); EcoRI-MfeI (L3); ApoI (L4); SacI (L5); HincII (L6); StuI (L7); TaqI (L8); and Sau3AI (L9). Fragments were ligated into the BamHI (L1, L2, L9), EcoRI (L3, L4), SacI (L5), HincII (L6, L7) or AccI (L8) sites of pJKI708. The nine libraries were transformed into TG2/R55 cells. After heat shock at 42 °C, the transformed cultures were incubated for 2 h at 37 °C in 1 ml LB medium, followed by addition of 1 ml LB+Sm+Sp broth and growth of the cultures O/N at 37 °C. The O/N cultures were centrifuged, washed with 0.9% NaCl solution and used as donors in crosses with 200 μl O/N cultures of the TG1Nal recipient strain as previously described50. After conjugation, the donor and recipient titers varied between 5.0 × 106 − 1.2 × 108 and 1.0−2.6 × 1010 CFU/ml, respectively. Transconjugants selected on LB + Nal + Sm + Sp plates were obtained only from libraries L1 (60 CFU/ml), L2 (30 CFU/ml) and L5 (4.0 × 104 CFU/ml). To ensure the isolation of all mobilizable regions, the whole experiment was repeated twice, which provided similar results.

One-step gene KO experiments

Gene KO experiments and elimination of the CmR marker gene from the KO alleles were conducted according to the one-step recombination method26 using the λ Red recombinase producer plasmid pJKI64833, a GmR derivative of pKD46. As R55 has multiple resistance genes (floR, cat, aadB, oxa21, qacEΔ1, sulI, mer), this plasmid was not applicable for one-step gene KO, and thus we used its close relatives, R16a and IP40a, to delete the oriT, RecHS, traI, mobI, and orf128 genes. The KO fragments were amplified from the pKD3 template plasmid using primers R55_T2delfor – R55_T2delrev, R55_T1delfor – IP40/R16_T1delrev, deltraIR55for – deltraIR55rev, R55_001delstart – R55_001delstop and R55_128delfor – R55_128delrev, respectively.

Primer extension analysis

Total RNA was isolated from E. coli strain TG1 containing the plasmid pMSZ952 carrying the non-coding upstream region of mobI followed by the promoterless lacZ gene, or pJKI990 as a negative control. RNA isolation and primer extension were carried out as previously described34. Overnight cultures were diluted 1000× and grown at 37 °C to an OD600 of 0.6 in 10 ml LB without antibiotics. Cells were harvested from 2.5 ml cultures and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Next, 750 μl of lysis buffer (0.2 M Na-acetate pH 5.2, 1% SDS 10 mM EDTA) was added to the frozen pellet. After vortexing, the mixture was boiled for 2–3 min and then vortexed again for 2 min. Lysates were centrifuged (20 min, 16000 rcf, 4 °C), and the supernatants were extracted with 750 μl phenol and centrifuged again (10 min, 16000 rcf, 4 °C). Extraction was repeated with 720 μl phenol: chloroform (1:1) followed by 360 μl chloroform. RNA was precipitated by adding 200 μl 10 M LiCl to 600 μl supernatant followed by incubation on ice (1 hour) and centrifugation (10 min, 16000 rcf, 4 °C). The pellet was first washed with 2.5 M LiCl and then with 70% ethanol, centrifuged, air-dried and dissolved in 50 μl RNase-free water at 50 °C. Then, 20 μl (~10 μg) of total RNA was digested with 50 units of RNase-free DNaseI (Qiagen) in a final volume of 50 μl (10 min, 37 °C), and the enzyme was subsequently inactivated (10 min, 65 °C). The reaction mixture was subjected to phenol-chloroform extraction, followed by two washes with 70% ethanol and resuspension in 20 μl RNase-free water after drying. The RNA concentration was set at 0.5 μg/μl.

The primer extension reaction was performed using the RevertAid H Minus first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Fermentas). Ten pmoles of pUCfor21 primer was labeled in a 10-μl volume with 10 units of polynucleotide kinase (Fermentas) using 50 μCi [γ-32P] dATP (45 min, 37 °C). Subsequently, the enzyme was inactivated for 10 min at 68 °C. Approximately 5 μg of total RNA and 2 pmoles of32P-labeled primer were mixed, heated to 70 °C for 5 min, and then allowed to anneal at 37 °C for 5 min. The extension reactions were performed in RT buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 50 mM KCl, 4 mM MgCl2 10 mM DTT) with 1 mM dNTP and 20 units RiboLock ribonuclease inhibitor in a total volume of 20 μl (42 °C, 60 min) using 200 units of reverse transcriptase. The extension products were precipitated with ethanol, resuspended in 3 μl DEPC-treated water, and combined with 2 μl sequencing loading solution. The sequence ladder for the tester plasmids was generated with primer pUCfor 21 and pMSZ952 template plasmid using a Sequenase version 2.0 DNA sequencing kit (USB) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The products of each reaction were electrophoresed on a 6% denaturing polyacrylamide gel at 1800 V. The gel was exposed to a storage phosphor screen and scanned on a Storm 840 PhosphorImager (Amersham Biosciences).

Bioinformatics

Sequence alignments were generated using the MultAlin interface52. Protein structure modeling for MobI was conducted using Swiss-Model53 and Phyre254. All homology searches were performed with the NCBI BLAST server. IncA/C family plasmids were identified via a nucleotide megaBLAST search in GenBank with the repA gene of R55 as the query sequence. Plasmids having a repA homolog with ≥98% alignment length coverage and ≥80% identity for a repA gene of R55, and carrying the large parts of the conserved backbone of R55 were considered as IncA/C plasmid (Supplementary Table 2). The potential secondary structure of oriT was generated using the mFold webserver55.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article (and its Supplementary Information files).

References

Ventola, C. L. The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats. P T A peer-reviewed J. Formul. Manag. 40, 277–83 (2015).

Lanka, E. & Wilkins, B. M. DNA processing reactions in bacterial conjugation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 64, 141–169 (1995).

Cabezón, E., Ripoll-Rozada, J., Peña, A., de la Cruz, F. & Arechaga, I. Towards an integrated model of bacterial conjugation. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 39, 81–95 (2015).

de la Cruz, F., Frost, L. S., Meyer, R. J. & Zechner, E. L. Conjugative DNA metabolism in Gram-negative bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 34, 18–40 (2010).

Frost, L. S., Ippen-Ihler, K. & Skurray, R. A. Analysis of the sequence and gene products of the transfer region of the F sex factor. Microbiol. Rev. 5, 162–210 (1994).

Avila, P., Núñez, B. & de la Cruz, F. Plasmid R6K contains two functional oriTs which can assemble simultaneously in relaxosomes in vivo. J. Mol. Biol. 261, 135–43 (1996).

Fürste, J. P., Pansegrau, W., Ziegelin, G., Kröger, M. & Lanka, E. Conjugative transfer of promiscuous IncP plasmids: interaction of plasmid-encoded products with the transfer origin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86, 1771–5 (1989).

Pansegrau, W. et al. Complete nucleotide sequence of Birmingham IncPα plasmids. J. Mol. Biol. 239, 623–663 (1994).

Francia, M. V. & Clewell, D. B. Transfer origins in the conjugative Enterococcus faecalis plasmids pAD1 and pAM373: Identification of the pAD1 nic site, a specific relaxase and a possible TraG-like protein. Mol. Microbiol. 45, 375–395 (2002).

Wisniewski, J. A. et al. TcpM: A novel relaxase that mediates transfer of large conjugative plasmids from Clostridium perfringens. Mol. Microbiol. 99, 884–896 (2016).

Pansegrau, W. & Lanka, E. Common sequence motifs in DNA relaxases and nick regions from a variety of DNA transfer systems. Nucleic Acids Res. 19, 3455 (1991).

Ziegelin, G., Furste, J. P. & Lanka, E. TraJ protein of plasmid RP4 binds to a 19-base pair invert sequence repetition within the transfer origin. J. Biol. Chem. 264, 11989–11994 (1989).

Pansegrau, W., Balzer, D., Kruft, V., Lurz, R. & Lanka, E. In vitro assembly of relaxosomes at the transfer origin of plasmid RP4. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 87, 6555–6559 (1990).

Moncalián, G. & de la Cruz, F. DNA binding properties of protein TrwA, a possible structural variant of the Arc repressor superfamily. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Proteins Proteomics 1701, 15–23 (2004).

de Paz, H. D. et al. Functional dissection of the conjugative coupling protein TrwB. J. Bacteriol. 192, 2655–2669 (2010).

Matilla, I. et al. The conjugative DNA translocase TrwB is a structure-specific DNA-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 17537–17544 (2010).

Harmer, C. J. & Hall, R. M. The A to Z of A/C plasmids. Plasmid 80, 63–82 (2015).

Garcillán-Barcia, M. P., Francia, M. V. & de la Cruz, F. The diversity of conjugative relaxases and its application in plasmid classification. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33, 657–687 (2009).

Carraro, N., Matteau, D., Luo, P., Rodrigue, S. & Burrus, V. The master activator of IncA/C conjugative plasmids stimulates genomic islands and multidrug resistance dissemination. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004714 (2014).

Carraro, N. et al. Development of pVCR94ΔX from Vibrio cholerae, a prototype for studying multidrug resistant IncA/C conjugative plasmids. Front. Microbiol. 5, e44 (2014).

Ceccarelli, D., Daccord, A., René, M. & Burrus, V. Identification of the origin of transfer (oriT) and a new gene required for mobilization of the SXT/R391 family of integrating conjugative elements. J. Bacteriol. 190, 5328–38 (2008).

Welch, T. J. et al. Multiple antimicrobial resistance in plague: an emerging public health risk. PLoS One 2, e309 (2007).

Fricke, W. F. et al. Comparative genomics of the IncA/C multidrug resistance plasmid family. J. Bacteriol. 191, 4750–4757 (2009).

Miyazaki, R. & van der Meer, J. R. A dual functional origin of transfer in the ICEclc genomic island of Pseudomonas knackmussii B13. Mol. Microbiol. 79, 743–758 (2011).

Francia, M. V. et al. Completion of the nucleotide sequence of the Enterococcus faecalis conjugative virulence plasmid pAD1 and identification of a second transfer origin. Plasmid 46, 117–27 (2001).

Datsenko, K. A. & Wanner, B. L. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 6640–5 (2000).

Douard, G., Praud, K., Cloeckaert, A. & Doublet, B. The Salmonella genomic island 1 is specifically mobilized in trans by the IncA/C multidrug resistance plasmid family. PLoS One 5, e15302 (2010).

Doublet, B. et al. Complete nucleotide sequence of the multidrug resistance IncA/C plasmid pR55 from Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated in 1969. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67, 2354–2360 (2012).

Rose, R. E. The nucleotide sequence of pACYC177. Nucleic Acids Res. 16, 356 (1988).

Szabó, M. et al. Characterization of two multidrug-resistant IncA/C plasmids from the 1960s by using the MinION sequencer device. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 60, 6780–6786 (2016).

Witchitz, J. L. & Chabbert, Y. A. [Transferable resistance to gentamicin. I. Expression of the resistance character]. Ann. Inst. Pasteur (Paris). 121, 733–42 (1971).

Chabbert, Y. A., Scavizzi, M. R., Witchitz, J. L., Gerbaud, G. R. & Bouanchaud, D. H. Incompatibility groups and the classification of f-resistance factors. J. Bacteriol. 112, 666–675 (1972).

Kiss, J. et al. The master regulator of IncA/C plasmids is recognized by the Salmonella Genomic island SGI1 as a signal for excision and conjugal transfer. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 8735–8745 (2015).

Murányi, G., Szabó, M., Olasz, F. & Kiss, J. Determination and analysis of the putative AcaCD-responsive promoters of Salmonella Genomic Island 1. PLoS One 11, e0164561 (2016).

Carraro, N. et al. Salmonella genomic island 1 (SGI1) reshapes the mating apparatus of IncC conjugative plasmids to promote self-propagation. PLOS Genet. 13, e1006705 (2017).

McMurry, L., Petrucci, R. E. & Levy, S. B. Active efflux of tetracycline encoded by four genetically different tetracycline resistance determinants in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 77, 3974–7 (1980).

Sekiguchi, J. I. et al. KHM-1, a novel plasmid-mediated metallo-β-lactamase from a Citrobacter freundii clinical isolate. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52, 4194–4197 (2008).

Lum, P. L., Rodgers, M. E. & Schildbach, J. F. TraY DNA recognition of its two F factor binding sites. J. Mol. Biol. 321, 563–578 (2002).

Godziszewska, J., Kulińska, A. & Jagura-Burdzy, G. MobC of conjugative RA3 plasmid from IncU group autoregulates the expression of bicistronic mobC-nic operon and stimulates conjugative transfer. BMC Microbiol. 14, 235 (2014).

Abo, T., Inamoto, S. & Ohtsubo, E. Specific DNA binding of the TraM protein to the oriT region of plasmid R100. J. Bacteriol. 173, 6347–6354 (1991).

Lorenzo-Díaz, F., Solano-Collado, V., Lurz, R., Bravo, A. & Espinosa, M. Autoregulation of the synthesis of the MobM relaxase encoded by the promiscuous plasmid pMV158. J. Bacteriol. 194, 1789–1799 (2012).

Kurenbach, B. et al. The TraA relaxase autoregulates the putative type IV secretion-like system encoded by the broad-host-range Streptococcus agalactiae plasmid pIP501. Microbiology 152, 637–645 (2006).

O’Connor, M. B., Kilbane, J. J. & Malamy, M. H. Site-specific and illegitimate recombination in the oriV1 region of the F factor. DNA sequences involved in recombination and resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 189, 85–102 (1986).

Broach, J. R., Guarascio, V. R. & Jayaram, M. Recombination within the yeast plasmid 2 μ circle is site-specific. Cell 29, 227–234 (1982).

Hoess, R., Abremski, K. & Sternberg, N. The nature of the interaction of the P1 recombinase Cre with the recombining site loxP. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 49, 761–768 (1984).

Martinez, F. A. C., Benmohamed, A. & Szatmari, G. Xer site specific recombination: double and single recombinase systems. 8, 1–18 (2017).

Nicolas, E. et al. The Tn3-family of replicative transposons. Microbiol. Spectr. 1, 1–32 (2015).

Lane, D., de Feyter, R., Kennedy, M., Phua, S.-H. & Semon, D. D protein of miniF plasmid acts as a repressor of transcription and as a site-specific resolvase. Nucleic Acids Res. 14, 9713–9728 (1986).

Sambrook, J., Fritsch, E. F. & Maniatis, T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. Cold Spring Harbor, NY. New York (1989).

Kiss, J., Nagy, B. & Olasz, F. Stability, entrapment and variant formation of Salmonella Genomic Island 1. PLoS One 7, e32497 (2012).

Miller, J. H. Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press. Cold Spring Harbor, NY. New York (1972).

Corpet, F. Multiple sequence alignment with hierarchical clustering. Nucleic Acids Res. 16, 10881–90 (1988).

Arnold, K., Bordoli, L., Kopp, J. & Schwede, T. The SWISS-MODEL workspace: A web-based environment for protein structure homology modelling. Bioinformatics 22, 195–201 (2006).

Kelley, L. A., Mezulis, S., Yates, C. M., Wass, M. N. & Sternberg, M. J. E. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 10, 845–858 (2015).

Zuker, M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3406–3415 (2003).

Gibson, T. J. Studies on the Epstein-Barr virus genome. Thesis. (Cambridge. UK, 1984).

Gonzy-Treboul, G., Karmazyn-Campelli, C. & Stragier, P. Developmental regulation of transcription of the Bacillus subtilis ftsAZ operon. J. Mol. Biol. 224, 967–979 (1992).

Short, J. M., Fernandez, J. M., Sorge, J. A. & Huse, W. D. Lambda ZAP: A bacteriophage lambda expression vector with in vivo excision properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 16, 7583–7600 (1988).

Dente, L., Cesareni, G. & Cortese, R. pEMBL: A new family of single stranded plasmids. Nucleic Acids Res. 11, 1645–1655 (1983).

Kiss, J. & Olasz, F. Formation and transposition of the covalently closed IS30 circle: the relation between tandem dimers and monomeric circles. Mol. Microbiol. 34, 37–52 (1999).

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Axel Cloeckaert and Benoit Doublet (INRA, Nouzilly, France) for providing the IncA/C plasmids R55, R16a and IP40a. We thank Erika Sztánáné-Keresztúri and Mária Turai for the excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund K 105635 to J. K.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.K. and F.O. conceived the project. A.H., M.S. and J.K. designed and carried out the experiments and analyzed the data. M.S. performed the bioinformatic analyses. M.S. and J.K. prepared the figures, J.K. and A.H. wrote the paper and all authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hegyi, A., Szabó, M., Olasz, F. et al. Identification of oriT and a recombination hot spot in the IncA/C plasmid backbone. Sci Rep 7, 10595 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11097-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-11097-0

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.