Abstract

Neuro-Behçet’s disease (NBD) is subcategorized into parenchymal-NBD (P-NBD) and non-parenchymal-NBD types. Recently, P-NBD has been further subdivided into acute P-NBD (A-P-NBD) and chronic progressive P-NBD (CP-P-NBD). Although an increasing number of studies have reported the various clinical features of A-P-NBD and CP-P-NBD over the last two decades, there was a considerable inconsistency. Two investigators systematically searched four electrical databases to detect studies that provided sufficient data to assess the specific characteristics of A-P-NBD and CP-P-NBD. All meta-analysis was carried out by employing the random-model generic inverse variance method. We included 11 reports consisted of 184 A-P-NBD patients and 114 CP-P-NBD patients. While fever (42% for A-P-NBD, 5% for CP-P-NBD, p < 0.001, I2 = 93%) was more frequently observed in A-P-NBD cases; sphincter disturbances (9%, 34%, P = 0.005, I2 = 87%), ataxia (16%, 57%, P < 0.001, I2 = 92%), dementia (7%, 61%, P < 0.001, I2 = 97%), confusion (5%, 18%, P = 0.04, I2 = 76%), brain stem atrophy on MRI (4%, 75%, P < 0.001, I2 = 98%), and abnormal MRI findings in cerebellum (7%, 54%, P = 0.02, I2 = 81%) were more common in CP-P-NBD. Cerebrospinal fluid cell count (94/mm3, 11/mm3, P = 0.009, I2 = 85%) was higher in A-P-NBD cases. We demonstrated that A-P-NBD and CP-P-NBD had clearly different clinical features and believe that these data will help future studies investigating P-NBD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Behçet’s disease (BD) is a multisystem inflammatory disease with unknown etiology. The classical frequent symptoms are uveitis, genital ulcers, skin lesions, and recurrent oral aphthous ulcers1. The prevalence of BD is high in the Middle East, the Mediterranean basin, and the Far East regions, but it is rare in northern Europe, the American continents, and southern Africa. Central nervous system (CNS) involvement in BD has remained one of the most serious complications of the disease since the first report by Knapp in19422. The conception of NBD (neuro- Behçet’s disease) was proposed by Cavara and D’Ermo3. The frequency of NBD greatly varies from 1.3%4 to 59%5 depending on the reports. The general consensus is that approximately 10% of BD patients have neurological involvement6, 7.

In our current understanding, there are two clinical categories of NBD, parenchymal-NBD (P-NBD) and nonparenchymal-NBD (NP-NBD)7,8,9. P-NBD, which is caused by parenchymal pathology, accounts for the majority of NBD. Some experts call P-NBD as intra-axial NBD, primary-NBD, or simply “NBD”. On the other hand, NP-NBD, which is usually caused by occlusion or hemorrhage of the main vascular structures, or aneurysm in the CNS, is relatively rare. To indicate NP-NBD, some researchers use alternative wordings such as vasculo-NBD, secondary NBD, or extra-axial NBD. The frequency of this subtype is reported 10 to 20% of all NBD patients from UK10 and Turkey11, 12, whereas it was extremely rare in Japan13, 14. Parenchymal-NBD is featured by diffuse brainstem, cerebral, optic, and spinal cord symptoms. Abnormal sign can appear depending on the site of involvement, typically brainstem atrophy and cerebral abnormal signs are observed. On the other hand, cerebral venous thrombosis, pseudo-tumor like intracranial hypertension, and acute meningeal syndrome are common forms of nonparenchymal-NBD. Cerebral sinus or vein thrombosis and meningeal enhancement may be revealed for MRI imaging of nonparenchymal-NBD7,8,9.

Because P-NBD shows heterogeneous clinical pictures, which require different therapeutic strategies, several lines of clinical subtyping of P-NBD patients had been shown in various studies7, 9, 11. Hirohata et al. have proposed clinical-orientated and simple classification in which P-NBD is further classified into an acute type and chronic progressive type, depending on its clinical course13, 15, 16. Acute P-NBD (A-P-NBD) typically features acute and transient symptoms such as fever and hemiparesis accompanied by inflammatory features including elevated cell count in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), while chronic progressive P-NBD (CP-P-NBD) is characterized by ataxia, dementia, incontinence, and brainstem atrophy17, 18. It is sometimes difficult to clearly classify some P-NBD cases into A-P-NBD and CP-P-NBD categories. A portion of P-NBD patients can experience acute first attack and following chronic progressive course. Over the last two decades, an increasing number of studies have reported the various clinical features of A-P-NBD and CP-P-NBD. However, these reports indicated inconsistencies in the prevalence of symptoms, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, and laboratory results. Therefore, we designed this systematic review and meta-analysis to reveal the key features of A-P-NBD and CP-P-NBD and to clearly differentiate them.

Methods

Study overview

This study was conducted following the standard method of meta-analysis19. Institutional review board approval and patient consent were not required because of the review nature of this study.

Eligibility criteria

We planned to include case-series, cohort studies, case-control studies, cross-sectional studies, and randomized trials that provided sufficient data to assess the specific characteristics of A-P-NBD and CP-P-NBD. To calculate the pooled value, each study had to include at least two cases in a disease category. Thus, a single-case report was excluded. The reports had to be published as English full articles. Non-English reports and conference abstracts were excluded. Review articles without original data were also excluded. A study should assess at least one of the demographic characteristics, symptoms, MRI findings, and laboratory data listed in the Table 1. Reports that described P-NBD patients with a specific co-morbidity or a symptom were excluded. For example, a study that included only patients who had both A-P-NBD and headache was excluded. A study that evaluated P-NBD and NP-NBD collectively was not accepted. Although diagnostic criteria proposed by the International Study Group for Behcet’s Disease 1990 and that by International consensus 2014 was preferred7, 20, other criteria were also accepted.

Literature search strategy

In the electronic database search, we used Pubmed, EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, and Web of Science on April 1st, 2016. We used the following search formula for Pubmed without any limitation: neuro AND (Behcet’s[title] OR Behçet’s[title] OR Behcet[title] OR Behçet[title]) AND ((randomi* OR RCT OR case-control OR cohort OR cross-sectional OR epidemiol* OR prospective OR retrospective) OR ((acute OR progressive OR parenchymal OR non-parenchymal OR vasculo) AND ((symptom OR “headache” OR headache OR fever OR hemiparesis OR paraparesis OR dysarthria OR ataxia OR dementia OR psychiatr* OR seizure OR epilepsy OR incontinence OR dizziness OR vertigo OR movement OR sensory OR “cranial nerve” OR confusion OR coma OR optic OR visual OR pyramidal OR (spinal cord) OR tumor OR tumour OR (venous thrombosis)) OR (MRI OR “Magnetic resonance imaging” OR CT OR “computed tomography” OR “brain stem” OR “spinal fluid” OR CSF OR (HLA B51))))). We used similar search formulas for EMBASE, the Cochrane Library, and Web of Science (Supplementary Text 1).

We also manually searched published reviews and included original studies.

Duplicate use of the same data was excluded carefully. Two investigators (MI, NH) independently screened and scrutinized each article. Discrepancies between the investigators were resolved by discussion.

Study selection

Two researchers (MI, NH) screened the articles for possible inclusion by reading only the title and abstract independently. Then, the two researchers independently scrutinized the full text of articles that had not been excluded by at least one researcher. Duplicate use of the same data was cautiously assessed. The final inclusion was decided by debate between the two researchers.

Data extraction

The two researchers (MI, NH) independently extracted the data from the original studies. “First attack” was regarded as A-P-NBD. However, “second attack” and “remission and relapsing type” were excluded.

Statistical analysis

All meta-analysis was carried out by employing the random-model generic inverse variance method using Review Manager ver. 5.3 (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK)21. The standard error for binary data was estimated using Wilson score interval22. The heterogeneity assessed by I² statistic > 75% was regarded as considerable heterogeneity21.

Results

Study search and study characteristics

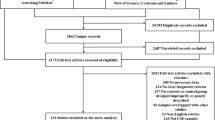

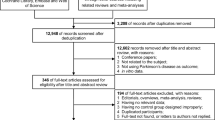

The PRISMA flowchart for the study search is shown in Fig. 1. Of the 581 articles that we found through the primary search, 317, 238, and 26 were excluded through removal of duplication, screening, and full-article reading, respectively (Fig. 1). Notably, Hirohata et al. and Akman et al. published reports repeatedly using the same cohorts of patients, most of which were excluded from the current systematic review. Our hand search found no eligible articles.

Among the finally included 10 reports, five were from Japan, two were from Turkey, and one each was from Italy, Iran, and France14, 16, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. The most commonly used criteria for diagnosis of BD was the International Study Group for Behçet’s disease 1990 criteria20, which was used in eight studies. One study used the International Study Group for Behçet’s disease 1992 criteria31 and the others used their own definition of BD (Table 1).

The number of participants in each study ranged from two to 115, with a median of 10. The total number of subjects was 320, consisting of 205 A-P-NBD patients and 115 CP-P-NBD patients. Of note, “second attack” and “remission and relapsing type” were excluded from this study. When acute and chronic progressive P-NBD were assessed collectively, 68.6% and 31.4% of NBD were men and women, respectively (Table 2). Onset of BD was at 39.0 years of age and that of NBD was at 42.9 years of age (Table 2).

Comparison of A-P-NBD and CP-P-NBD

Background characteristics

No differences were found concerning age of BD onset (A-P-NBD 39.2 years, CP-P-NBD 39.3 years, p = 0.99, I2 = 0%) and that of NBD onset (A-P-NBD 43.1, CP-P-NBD 43.3, p = 0.98, I2 = 0%). Men were in the majority for both A-P-NBD and CP-P-NBD (Table 2). Our results showed no difference in the frequency of HLA-B51 positive between acute and chronic progressive P-NBD patients (A-P-NBD 46.2%, CP-P-NBD 56.1, p = 0.55, I2 = 0%). Although supported by only a single study, smoking history (A-P-NBD 69.0%, CP-P-NBD 91.0%, p = 0.005, I2 = 87.5%) and previous use of cyclosporine (A-P-NBD 34.0%, CP-P-NBD 2.9%, p < 0.001, I2 = 95.3%) showed distinct differences between the two groups (Table 2, Fig. 2).

Symptoms

Fever (A-P-NBD 56.6%, CP-P-NBD 2.9%, p < 0.001, I2 = 98.3%) was more frequently observed in patients with A-P-NBD, whereas the frequencies of confusion (A-P-NBD 4.7%, CP-P-NBD 17.6%, p = 0.04, I2 = 76%), dementia (A-P-NBD 12.6%, CP-P-NBD 53.4%, p = 0.03, I2 = 78.6%), dysarthria (A-P-NBD 18.5%, CP-P-NBD 42.9%, p = 0.008, I2 = 85.9%), and ataxia (A-P-NBD 16.5%, CP-P-NBD 53.3%, p = 0.002, I2 = 89.5%) were higher in CP-P-NBD cases than in A-P-NBD cases (Table 2, Fig. 2). Otherwise, there were no differences in prevalence of neurological symptoms and focal signs between two groups (Table 2).

MRI findings

Eight of 10 studies analyzed MRI findings of imaging modalities to illustrate neurological lesions in a total of 275 BD patients. Various abnormal findings were documented, though such findings were negative in 34.3% of A-P-NBD and 28.7% of CP-P-NBD (p = 0.86, I2 = 0%).

Brain stem atrophy on MRI (A-P-NBD 11.9%, CP-P-NBD 76.3%, p < 0.001, I2 = 93%) and abnormal MRI findings for cerebellum (A-P-NBD 3.5%, CP-P-NBD 51.3%, p = 0.03, I2 = 79.1%) were more frequently observed for patients with CP-P-NBD, though “brain stem any finding” was not different between both groups (A-P-NBD 59.7%, CP-P-NBD 64.8%, p = 0.81, I2 = 0%).

There were no significant differences in the prevalence of abnormal findings for thalamus (A-P-NBD 12.8%, CP-P-NBD 12.6%, p = 0.99, I2 = 0%), white matter (A-P-NBD 15.9%, CP-P-NBD 37.5%, p = 0.33, I2 = 0%), or basal ganglia (A-P-NBD 48.2%, CP-P-NBD 35.3%, p = 0.72, I2 = 0%).

Laboratory data

The pooled CSF cell count of 156.2/mm3 in A-P-NBD was higher than that of 27.2/mm3 (95%CI: 0-54.4) in CP-P-NBD (p = 0.02). On the other hand, CSF IL-6 levels (A-P-NBD 65.4 pg/mL, CP-P-NBD 95.9 pg/mL, p = 0.62, I2 = 0%) and CSF protein levels (A-P-NBD 112.9 mg/dL, CP-P-NBD 78.9 mg/dL, p = 0.16, I2 = 50.4%) were not significantly different between the two groups.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we analyzed the characteristics in 320 patients with P-NBD. To the best of our knowledge, our report is the first systematic review to clarify the differences between A-P-NBD and CP-P-NBD. We showed that the clinical features in the A-P-NBD and CP-P-NBD were distinct besides disease duration and chronological clinical course. The patients with A-P-NBD generally present episodic meningitis and/or brainstem encephalitis with high fever and elevated CSF cell count. On the other hand, confusion, dementia, dysarthria, and ataxia were more common in CP-P-NBD. Besides the gradual progression of these symptoms, cerebellar and brain stem atrophy shown by MRI appear shared features with neurodegenerative disorders rather than other immune mediated neurological diseases. These features in individual clinical phenotypes are incorporated in preliminary diagnostic criteria of A-P-NBD and CP-P-NBD proposed by Hirohata and the Behcet’s Disease Research Committee, Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Labour, Japan14.

It is important that physicians are aware of these differences of clinical presentation between the two types of P-NBD, because the distinction may help with decision-making on treatment and expecting prognosis. Currently, no treatment option for P-NBD have been supported by randomized trials9, 32, 33. Besides low incidence of P-NBD, the clinical heterogeneity among P-NBD cases makes it difficult to obtain evidence for the therapeutic strategy. The current study revealed clearly distinctions in clinical symptoms, MRI findings, and CSF data between A-P-NBD and CP-P-NBD, suggesting differences in pathophysiology between them. It is essential to differentiate the two types of P-NBD to determine the best therapeutic strategy. Indeed, clinical manifestations of A-P-NBD subside in response to moderate to high dose of corticosteroid and the relapse is significantly suppressed by colchicine34. On the other hand, few studies have shown therapeutic effects of corticosteroid and conventional immunosuppressants on CP-P-NBD except methotrexate35. Methotrexate is recommended as the first line therapy for CP-P-NBD in the guidelines for management of NBD from Behcet’s Disease Research Committee, Ministry of Health, Welfare, and Labour, Japan. Favorable clinical outcomes of TNF inhibitors for both types of NBD have been accumulated including prospective study36.

Cyclosporine neurotoxicity in BD patients is well recognized as mentioned in EULAR recommendations for the management of BD32. The previous use of cyclosporine was exclusively associated with A-P-NBD, though it was analyzed in only one study14. The drug related A-P-NBD is generally reversible by discontinuation of cyclosporine with corticosteroids, as the natural onset disease.

Distinction between A-P-NBD and CP-P-NBD was originally advocated in Japan17, 18. Ideguchi et al.13 showed the difference of symptoms and MRI findings between the two categories of P-NBD by reviewing 38 patients with A-P-NBD and 15 patients with CP-P-NBD. They revealed that fever and headache were prevalent for acute NBD and that personality change, sphincter disturbance, involuntary movement, and ataxia were predominant in patients with CP-P-NBD. These findings were generally compatible with our analysis.

Hirohata et al.14 showed that the CSF cell count is increased in the acute phase of A-P-NBD. CSF IL-6 level was higher than normal range in both A-P-NBD and CP-P-NBD groups (Table 2). CSF IL-6 level is often elevated in meningitis patients, thus, it is reasonable that CSF IL-6 level is increased at acute phase and decreased along the remission14. On the other hand, persistent elevation of CSF IL-6 is characteristic for CP-P-NBD (Fig. 2)37. Akman-Demir et al.23. in Turkey also showed similar CSF findings in A-P-NBD and CP-P-NBD, but not NP-NBD23.Furthermore, Kikuchi et al. showed that the progression rate of brain stem atrophy evaluated by MRI was closely correlated with CSF IL-6 elevation38. Interestingly, CSF IL-6 could be an activity marker for P-NBD patients even for those having normal range of CSF cell count and protein level23. This is not the case for serum IL-6 level23, 39. A few case reports have shown therapeutic effect of anti-IL-6 receptor antibody, tocilizumab, on CP-P-NBD40, 41, though this should be validated in a larger number of patients.

Both genetic and environmental factors have been considered to affect onset and clinical course of BD42. Especially, a number of studies have focused on association of HLA-B51 with clinical phenotypes of BD. A meta-analysis by Maldini et al. have shown that frequency of HLA–B51 is not higher in a whole of NBD patients than other subtypes of BD patients43. The largest study in the included researches was carried out by Noel et al. in France (Table 2), whose goal was to reveal the prognostic factor of P-NBD16. Likewise, Aramaki et al. also identified HLA-B51 and smoking as independent predisposing factors to CP-P-NBD44. These findings suggested that HLA-B51 is associated with unfavorable clinical course of NBD. However, the present study failed to show difference in the prevalence of HLA-B51 between A-P-NBD and CP-P-NBD patients (Table 2).

We need to comment on some limitations of the current study. First, NBD diagnosis was not oriented from the latest recommendation7. Similarly, there might be a slight inconsistency of definition of A-P-NBD and CP-P-NBD between studies. Therefore, diagnosis of NBD and nomenclatures of the clinical subtypes were not necessarily consistent among the studies, though the concepts were similar. In addition, clinical symptoms and MRI findings were evaluated by each investigator’s criteria. Second, as many as five out of the 10 included studies were from Japan. However, the data sources in this study are widely distributed in both sides of the Silk Road; 139, 115, 52, 8, and 2 cases were derived from reports from Japan, France, Turkey Iran, and Italy, minimizing regional bias. Third, we could not directly access the raw data of each patient; thus, detailed analysis concerning combinations and chronological change of signs and symptoms were not plausible. Further analysis using individual patient data may be interesting.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we performed a first systematic review and meta-analysis to discriminate the clinical presentation of A-P-NBD and CP-P-NBD. According to 10 studies with 205 A-P-NBD cases and 111 CP-P-NBD cases, fever and elevated CSF cell count featured A-P-NBD, whereas CP-P-NBD was characterized by sphincter disturbances, ataxia, dementia, confusions, brain stem atrophy, and abnormal MRI findings in cerebellum. Thus, it is important to recognize A-P-NBD and CP-P-NBD separately for management of NBD patients.

References

Sakane, T., Takeno, M., Suzuki, N. & Inaba, G. Behçet’s disease. N Engl J Med 341, 1284–1291, doi:10.1056/NEJM199910213411707 (1999).

Knapp, P. Beitrag zur Symptomatologie und Therapie der rezidivierenden Hypopyoniritis und der begleitenden aphthösen Schleimhauterkrankungen. (Schwabe, 1941).

Cavara, V. & D’Ermo, F. A case of neuro-Behçet’s syndrome. Acta XVII Concili Ophtalmologici 3, 1489 (1954).

Tursen, U., Gurler, A. & Boyvat, A. Evaluation of clinical findings according to sex in 2313 Turkish patients with Behcet’s disease. International journal of dermatology 42, 346–351 (2003).

Farah, S. et al. Behcet’s syndrome: a report of 41 patients with emphasis on neurological manifestations. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry 64, 382–384 (1998).

Al-Araji, A., Sharquie, K. & Al-Rawi, Z. Prevalence and patterns of neurological involvement in Behcet’s disease: a prospective study from Iraq. Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry 74, 608–613 (2003).

Kalra, S. et al. Diagnosis and management of Neuro-Behçet’s disease: international consensus recommendations. Journal of neurology 261, 1662–1676 (2014).

Serdaroglu, P. Behcet’s disease and the nervous system. Journal of neurology 245, 197–205, doi:10.1007/s004150050205 (1998).

Al-Araji, A. & Kidd, D. P. Neuro-Behcet’s disease: epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and management. Lancet Neurology 8, 192–204 (2009).

Kidd, D. The prevalence of Behcet’s syndrome and its neurological complications in Hertfordshire, U.K. Advances in experimental medicine and biology 528, 95–97, doi:10.1007/0-306-48382-3_19 (2003).

Akman-Demir, G., Serdaroglu, P. & Tasçi, B. Clinical patterns of neurological involvement in Behcet’s disease: Evaluation of 200 patients. Brain: a journal of neurology 122, 2171–2181 (1999).

Siva, A. Vasculitis of the nervous system. Journal of neurology 248, 451–468 (2001).

Ideguchi, H. et al. Neurological manifestations of Behçet’s disease in Japan: A study of 54 patients. Journal of neurology 257, 1012–1020 (2010).

Hirohata, S. et al. Clinical characteristics of neuro-Behcet’s disease in Japan: a multicenter retrospective analysis. Modern Rheumatology 22, 405–413, doi:10.1007/s10165-011-0533-5 (2012).

Hirohata, S. & Kikuchi, H. Changes in biomarkers focused on differences in disease course or treatment in patients with neuro-Behçet’s disease. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan) 51, 3359–3365 (2012).

Noel, N. et al. Long-term outcome of neuro-behçet’s disease. Arthritis and Rheumatology 66, 1306–1314 (2014).

Kurohara, K., Matsui, M. & Kuroda, Y. [An immunopathological study during steroid-responsive and steroid-nonresponsive stages on a patient with neuro-Behçet’s disease]. Rinsho Shinkeigaku 33, 455–458 (1993).

Hirohata, S. [Central nervous system involvement in rheumatic diseases]. Nihon Rinsho 57, 409–412 (1999).

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J. & Altman, D. G. Reprint–preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Physical therapy 89, 873–880 (2009).

Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet’s disease. International Study Group for Behçet’s Disease. Lancet 335, 1078-1080 (1990).

Higgins, J. & Green, S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions 5.1.0[updated May 2011]. The cochrane library (2005).

Wilson, E. B. Probable inference, the law of succession, and statistical inference. Journal of the American Statistical Association 22, 209–212 (1927).

Akman-Demir, G. et al. Interleukin-6 in neuro-Behcet’s disease: Association with disease subsets and long-term outcome. Cytokine 44, 373–376, doi:10.1016/j.cyto.2008.10.007 (2008).

Coban, O. et al. Masked assessment of MRI findings: is it possible to differentiate neuro-Behcet’s disease from other central nervous system. Neuroradiology 41, 255–260 (1999).

De Cata, A. et al. Prolonged remission of neuro-Behcet disease following autologous transplantation. International journal of immunopathology and pharmacology 20, 91–96 (2007).

Haghighi, A. B., Sarhadi, S. & Farahangiz, S. MRI findings of neuro-Behcet’s disease. Clinical rheumatology 30, 765–770, doi:10.1007/s10067-010-1650-9 (2011).

Kanoto, M., Hosoya, T., Toyoguchi, Y. & Oda, A. Brain stem and cerebellar atrophy in chronic progressive neuro-Behcet’s disease. European journal of radiology 82, 146–150, doi:10.1016/j.ejrad.2012.04.040 (2013).

Matsui, T. et al. An attack of acute neuro-Behçet’s disease during the course of chronic progressive neuro-Behçet’s disease: Report of two cases. Modern Rheumatology 20, 621–626 (2010).

Nakamura, Y. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and brain-stem auditory evoked potentials in neuro-Behcet’s disease. Journal of neurology 241, 481–486 (1994).

Sumita, Y. et al. Elevated BAFF Levels in the Cerebrospinal Fluid of Patients with Neuro-Behçet’s Disease: BAFF is Correlated with Progressive Dementia and Psychosis. Scandinavian journal of immunology 75, 633–640 (2012).

Evaluation of diagnostic (‘classification’) criteria in Behcet’s disease–towards internationally agreed criteria. The International Study Group for Behcet’s disease. British journal of rheumatology 31, 299-308 (1992).

Hatemi, G. et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of Behçet disease. Annals of the rheumatic diseases 67, 1656–1662 (2008).

Hatemi, G. et al. Management of Behcet disease: a systematic literature review for the European League Against Rheumatism evidence-based recommendations for the management of Behcet disease. Ann Rheum Dis 68, 1528–1534, doi:10.1136/ard.2008.087957 (2009).

Hirohata, S. et al. Analysis of various factors on the relapse of acute neurological attacks in Behçet’s disease. Modern rheumatology / the Japan Rheumatism Association 24, 961–965 (2014).

Hirohata, S. et al. Retrospective analysis of long-term outcome of chronic progressive neurological manifestations in Behcet’s disease. Journal of the neurological sciences 349, 143–148, doi:10.1016/j.jns.2015.01.005 (2015).

Hibi, T. et al. Infliximab therapy for intestinal, neurological, and vascular involvement in Behcet disease: Efficacy, safety, and pharmacokinetics in a multicenter, prospective, open-label, single-arm phase 3 study. Medicine 95, e3863, doi:10.1097/md.0000000000003863 (2016).

Borhani Haghighi, A. et al. CSF levels of cytokines in neuro-Behçet’s disease. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery 111, 507–510 (2009).

Kikuchi, H., Takayama, M. & Hirohata, S. Quantitative analysis of brainstem atrophy on magnetic resonance imaging in chronic progressive neuro-Behçet’s disease. Journal of the neurological sciences 337, 80–85 (2014).

Hirohata, S. et al. Cerebrospinal fluid interleukin-6 in progressive Neuro-Behcet’s syndrome. Clinical immunology and immunopathology 82, 12–17 (1997).

Addimanda, O., Pipitone, N., Pazzola, G. & Salvarani, C. Tocilizumab for severe refractory neuro-Behcet: three cases IL-6 blockade in neuro-Behcet. Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism 44, 472–475, doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2014.08.004 (2015).

Talarico, R. et al. Behcet’s disease: features of neurological involvement in a dedicated centre in Italy. Clinical and experimental rheumatology 30, S69–S72 (2012).

Kirino, Y. et al. Continuous evolution of clinical phenotype in 578 Japanese patients with Behcet’s disease: a retrospective observational study. Arthritis Res Ther 18, 217, doi:10.1186/s13075-016-1115-x (2016).

Maldini, C., Lavalley, M. P., Cheminant, M., de Menthon, M. & Mahr, A. Relationships of HLA-B51 or B5 genotype with Behcet’s disease clinical characteristics: systematic review and meta-analyses of observational studies. Rheumatology (Oxford) 51, 887–900, doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ker428 (2012).

Aramaki, K., Kikuchi, H. & Hirohata, S. HLA-B51 and cigarette smoking as risk factors for chronic progressive neurological manifestations in Behcet’s disease. Modern rheumatology / the Japan Rheumatism Association 17, 81–82, doi:10.1007/s10165-006-0541-z (2007).

Borhani Haghighi, A., Sarhadi, S. & Farahangiz, S. MRI findings of neuro-Behcet’s disease. Clinical rheumatology 30, 765–770, doi:10.1007/s10067-010-1650-9 (2011).

Acknowledgements

No support in the form of grants, gifts, equipment, and/or drugs was provided.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.M. was involved in the analysis and drafting text/tables/figures. H.N. was responsible for study design and critical revision of the manuscript as a principal investigator and statistical advisor. T.M., S.E., Y.T., K.T., I.T., M.K., and Y.R. contributed for data acquisition. K.Y., T.M., H.S., I.Y., K.T., and M.N. provided general management of the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ishido, M., Horita, N., Takeuchi, M. et al. Distinct clinical features between acute and chronic progressive parenchymal neuro-Behçet disease: meta-analysis. Sci Rep 7, 10196 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09938-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-09938-z

This article is cited by

-

Diagnosis and management of Neuro-Behçet disease with isolated intracranial hypertension: a case report and literature review

BMC Neurology (2023)

-

Behçet-Syndrom

Gefässchirurgie (2019)

-

Behçet’s Syndrome and Nervous System Involvement

Current Neurology and Neuroscience Reports (2018)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.