Abstract

The effects of alcohol drinking and smoking on pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) mortality are contradictory. Individuals who were diagnosed as PDAC and hospitalized at the China National Cancer Center between January 1999 and January 2016 were identified and included in the study. Ultimately, 1783 consecutive patients were included in the study. Patients were categorized as never, ex-drinkers/smokers or current drinkers/smokers. Hazard ratios (HRs) of all-cause mortality and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using Cox proportional hazards models. Compared with never drinkers, the HRs were 1.25 for ever drinkers, 1.24 for current drinkers, and 1.33 for ex-drinkers (trend P = 0.031). Heavy drinking and smoking period of 30 or more years were positive prognostic factors for PDAC. For different smoking and alcohol drinking status, only subjects who are both current smokers and current drinkers (HR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.03–2.05) were associated with reduced survival after PDAC compared to those who were never smokers and never drinkers. Patients who are alcohol drinkers and long-term smokers before diagnosis have a significantly higher risk of PDAC mortality. Compared to those who neither smoker nor drink, only patients who both smokers and drinkers were associated with reduced survival from PDAC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is a leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide with over 330,000 new cases and approximately the same number of deaths annually1,2,3,4. Patient survival is greatly influenced by disease stage at presentation, but few other markers of survival have been well characterized.

Chronic alcohol intake can cause structural and functional impairment in the pancreas. These changes lead to advanced contact between cathepsin B (lysosomal enzyme that activates trypsinogen) and digestive enzymes, ultimately resulting in premature intracellular activation of digestive enzymes and autodigestive injury to the pancreas5. So far, data that elucidate the prognostic role of alcohol in patients with PDAC have been limited; moreover, they are contradictory6,7,8,9,10. Alcohol drinking was reported to decrease survival in patients with PDAC in some studies6, 9. However, several studies7, 8, 10 did not confirm this finding.

Cigarette smoke contains a complex mixture of over 4000 compounds that have carcinogenic effects, which influences all aspects of tumor biology including initiation, progression and metastasis through mutations, inflammation and immunosuppression11. Smoke exposure can increase the expression of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor-like growth factor (HB-EGF), leading to a faster progression of PDAC11. Several studies6, 10, 12,13,14,15,16 investigated the effects of smoking on PDAC survival. Some studies6, 10, 12, 15 have reported a positive association between smoking and overall survival from PDAC. On the other hand, other studies13, 14, 16 have found that smoking status was inversely associated with PDAC survival.

The aim of this study was to provide further information on the impact of smoking and alcohol consumption on overall survival after a diagnosis of PDAC, by analyzing data on a relatively large number of Chinese patients.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective cohort study using prospectively collected data was conducted at the Cancer Hospital of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, China National Cancer Center. Individuals who were diagnosed as PDAC and hospitalized between January 1999 and January 2016 were identified and included in the study. Histological or cytological confirmation was available for all the included patients. Histologically confirmed neuroendocrine tumors or other types of pancreatic tumors were excluded. All patients had no previous diagnosis of any cancer. The study protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the China National Cancer Center.

The following information were obtained by trained investigators from the medical records: sociodemographic characteristics, anthropometric measures (height and weight measured at diagnosis as well as usual adult weight reported by the patients), smoking (number of cigarettes per day (/d), duration of smoking, years since stopped smoking), and alcohol consumption (the volume of alcohol/d, duration of drinking, and, years since stopped drinking). Ex-drinkers were defined as subjects who had stopped drinking more than 1 year before cancer diagnosis. Ex-smokers were defined as those who had stopped smoking more than 1 year before cancer diagnosis. The amount of ethanol consumed daily was calculated in grams, and drinkers were categorized into three groups: light drinkers (<15.6 g/d), moderate drinkers (≥15.6 g/d to <53.5 g/d) and heavy drinkers (≥53.5 g/d). Smokers were categorized into two groups according to duration of smoking, long-term smokers (duration < 29 years) and short-term smokers (duration ≥ 29 years). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated according to Quetelet’s index (weight/height2, kg/m2). The BMI at diagnosis was calculated by the height and weight measured at diagnosis. The usual BMI was calculated by the height measured at diagnosis and self-reported usual adult weight, which was defined as the usual weight one year before the disease diagnosis. Information on clinical characteristics of pancreatic cancer (eg, tumor stage) was also recorded.

Vital status was ascertained using two different procedures. We obtained data from population registries from local authorities, municipal registration offices and local health units. Data were collected on date and place of information retrieval (if the subject was still alive), death, or migration outside of China. For patients whose information could not be ascertained through population registries, we obtained the vital status by calling the patients or next of kin. Information on cause(s) of death was not collected.

The end point was the death of patients or the last follow-up time (Marth 31, 2016). Eleven (0.6%) patients had missing information on date of diagnosis. 119 subjects (6.2%) were lost to follow-up or missed information on date of death Therefore a total of 1783 subjects (94.2%) were included in the final analysis. Overall, 143 patients were alive at the end of follow-up (maximum follow-up time of 17 years) and 1640 had died.

Statistical Analysis

Overall survival was analyzed using Kaplan-Meier product-limit survival curve estimates and log-rank tests for comparison between groups. Overall survival was defined as the time from date of diagnosis of pancreatic cancer to date of end of follow-up or death. In the figures, we cut follow-up time at 5 years. We tested the proportional hazards assumption by including time-dependent effects in the model (ie, a covariate for interaction of the predictor and the logarithm of survival time), and no violation was found. Hazard ratios (HRs) of all-cause mortality and the corresponding 95% CIs were estimated using Cox proportional hazards models and included terms for age, calendar period at diagnosis, sex, BMI and tumor stage. Furthermore, in the analyses on smoking and alcohol consumption, the latter covariates were reciprocally adjusted. All tests were 2-sided, and P < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) statistical software.

Results

A total of 1,783 consecutive patients with data available were identified and included in the study. Their median survival was 8.26 months and their 5-year overall survival was 4.2%.

Table 1 shows the main characteristics of 1,783 patients with PDAC included in the study and the corresponding HRs and 95% CIs for all-cause mortality. Approximately two thirds of the patients were aged 50 to 69 years at diagnosis, with a mean age of 58.7 years, and about 56.6% of the cases were males. Mean usual BMI and BMI at diagnosis were 24.19 kg/m2 and 23.3 kg/m2 respectively. About half of the patients had a BMI of less than 23 kg/m2 at diagnosis, however, only a third of the patients had a usual BMI of less than 23 kg/m2. More than 70% of the patients were diagnosed as metastatic PDAC. The HR of the female patients for all-cause mortality was 1.16 (95% CI, 1.01–1.33) versus the male patients. As compared with the patients in the resectable stage, the HR was 1.22 (95% CI, 1.03–1.62) for those in the unresectable and locally advanced stage, and 1.17 (95% CI, 0.93–1.48) for those in the metastatic stage. No meaningful difference in survival after PDAC emerged according to age, BMI at diagnosis and usual BMI.

Table 2 shows the distribution of the pancreatic cancer cases and their HRs of all-cause mortality according to tobacco smoking and alcohol drinking.

67.7% of the cases had never smoked, 23.9% were current smokers, 5.6% were ex-smokers, and 2.8% had missing smoking information. The corresponding median overall survival was 8.6 months in the never smokers, 7.9 months in the current smokers, and 7.1 months in the ex-smokers. Figure 1 shows the survival curves of the patients with PDAC according to their tobacco smoking. The former smokers had an insignificantly different survival rate as compared to the never smokers (log-rank test P = 0.67).

The multivariate HR (Table 2) was 1.01 (95% CI, 0.85–1.20) for the former smokers, 1.02 (95% CI, 0.87–1.21) for the current smokers, and 1.20 (95% CI, 0.85–1.68) for the ex-smokers versus the never smokers (P for trend = 0.59). With reference to the subjects who had stopped smoking—as compared with the never smokers—their HR was 1.54 (95% CI, 0.88–2.70) for the long-term ex-smokers (i.e., those who stopped smoking since > = 10 years ago) and 1.29 (95% CI, 0.83–2.18) for the short-term ex-smokers (P for trend = 0.93).

Increasing amount and duration of smoking had unfavorable effects on overall survival after pancreatic cancer, since the HR of death was 1.06 (95% CI, 0.85–1.32) for smoking up to 19 cigarettes/d and 1.94 (95% CI, 0.79–1.37) for 20 or more (P for trend = 0.44), and 1.04 (95% CI, 0.66–1.28) for a duration of smoking less than 30 years and 1.40 (95% CI, 1.11–1.76) for 30 or more years, as compared with the never smokers (P for trend = 0.15).

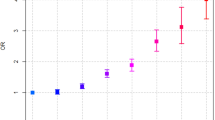

About 77.2% of the patients were never drinkers, 17.8% were current drinkers, 4.5% were ex-drinkers, and 0.5% had missing information on alcohol consumption. Figure 2 shows the survival curves of the patients with pancreatic cancer according to alcohol consumption. No meaningful difference in overall survival was reported among the never drinkers, current drinkers, and ex-drinkers, with a log-rank test P = 0.074. Compared with the never drinkers, the multivariate HR (Table 2) was 1.25 (95% CI, 1.02–1.54) for the former drinkers, 1.24 (95% CI, 1.00–1.54) for the current drinkers, and 1.33 (95% CI, 0.88–2.00) for the ex-drinkers (P for trend = 0.031). As for the association between the amount of alcohol consumption and survival, only heavy drinkers were associated with reduced survival after PDAC as compared with the never drinkers (HR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.03–2.05).

For different smoking and alcohol drinking statuses, only subjects who were both current smokers and drinkers (HR, 1.45; 95% CI, 1.03–2.05) were associated with reduced survival after PDAC as compared to those who were never smokers and never drinkers. Although the interaction between smoking and alcohol intake on survival was not statistically significant (P = 0.24). Figure 3 shows the survival curves of the patients with pancreatic cancer according to smoking and alcohol drinking status (log-rank test, P = 0.10).

Subgroup Analysis

After stratification by clinical stage, the HRs of all-cause mortality were also reported according to tobacco smoking and alcohol drinking. For the 217 pancreatic cancer patients who underwent pancreatectomy, a smoking period of 30 or more years (versus never smokers; HR, 1.90; 95% CI, 1.26–3.35) and a status of being both current smoker and current drinker (versus patients who were never smoker and never drinker; HR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.01–4.35) were positive factors for PDAC mortality (Supplemental Table 1).

For the 316 patients with unresectable and locally advanced pancreatic cancer, smoking 20 or more cigarettes/d (versus never smokers; HR, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.09–4.02) was the sole positive factor for PDAC mortality (Supplemental Table 2).

For the 1,250 patients with distant metastatic pancreatic cancer, only heavy drinkers were associated with reduced survival from PDAC as compared to the never drinkers (HR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.01–2.38) (Supplemental Table 3).

Discussion

The findings of this study confirmed a decreased survival rate of pancreatic cancer patients with alcohol drinking and long-term tobacco smoking.

From this investigation, we found a positive association between alcohol consumption and survival. When the amount of alcohol consumption was taken into consideration, only heavy drinkers were associated with a decreased survival rate. Light and moderate drinkers did not show the same result.

In contrast, many previous studies have expressed no association between alcohol intake and pancreatic cancer mortality7, 8, 10, 17. In one of the largest cohort studies published to date7, which included 3,012 pancreatic cancer cases, the risk ratio (RR) of pancreatic cancer death related to the consumption of at least 1 drink per day was 1.0 (95% CI, 0.9–1.1) for men and 1.0 (95% CI, 0.8–1.1) for women.

Two other investigators6, 9, however, got opposite results. In a retrospective case-control study6 involved 248 pancreatic cancer cases, the RR of pancreatic cancer mortality associated with consumption of alcohol was 1.83 (95% CI, 1.1–3.0) based on 163 cases. Another cohort study9 reported significantly higher risks of pancreatic cancer mortality associated with the consumption of 3 drinks/d (RR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.11–1.42) or at least 4 drinks/d (RR, 1.25; 95% CI, 1.11–1.42), while no association was found between pancreatic cancer mortality and “moderate” alcohol consumption (i.e., <3 drinks per day)9.

Several factors might be responsible for this phenomenon, although its underlying mechanism is currently unclear. The biological mechanism for the association between alcohol consumption and pancreatic cancer is not fully understood, but it is well recognized that long-term heavy intake causes chronic alcoholic pancreatitis18, an established risk factor for pancreatic cancer. In addition, ethanol is metabolized in the oxidative and non-oxidative manners19 in the pancreas. Go et al.20 hypothesized several mechanisms by which metabolites might affect inflammation and carcinogenesis, including activation of nuclear transcription factors, increased production of reactive oxygen species, and dysregulation of cell proliferation and apoptosis. Chronic alcohol intake can cause structural and functional impairment of the pancreas. These changes lead to advanced contact between cathepsin B, i.e., lysosomal enzyme that activates trypsinogen, and digestive enzymes, ultimately resulting in premature intracellular activation of digestive enzymes and autodigestive injury to the pancreas5.

Our study showed no meaningful difference between ever smoking and never smoking in terms of the prognosis of pancreatic cancer. But when taking the duration of smoking into consideration, we found a decreased survival rate among long-term smokers.

After stratification by clinical stage, positive factors for patients who underwent pancreatectomy included smoking period of 30 or more years, and smoking 20 or more cigarettes/d for patients with unresectable locally advanced PDAC.

A detrimental effect of smoking on survival has been previously reported for many kinds of cancer6, 17, 21, 22, especially those etiologically associated with tobacco, such as lung cancer6. The causal association between tobacco smoking and pancreatic cancer has been well established23, 24. However, few data are available on prediagnostic tobacco smoking as a determinant of survival after pancreatic cancer, with 7 studies showing significant critical roles of tobacco6,7,8, 10, 12, 15, 25, and 4 showing no association13, 14, 16, 17. Of course, only 1 study10 considered the effects of the amount and duration of smoking, except smoking status, and showed the poorest prognosis for current smokers in the categories of higher use, that is, 20 or more cigarettes/d and 30 or more years of smoking.

While the mechanisms underlying this phenomenon remained unclear, a possible explanation is that smokers might develop more aggressive tumors17. This is also supported by the prometastatic role of nicotine in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma according to its influence on the expression of matrix metalloproteinase 9 and the vascular endothelial growth factor26. In addition, the effect of smoking on survival requires a long time to accumulate.

In this study, there was a positive association between alcohol consumption and survival rate of the overall patients, but after stratification by smoking and alcohol drinking status, only patients who are both smokers and drinkers were associated with reduced survival from PDAC. The mechanisms underlying this phenomenon were unclear. A possible reason for this result is that the two factors can interact with each other and promote the development of pancreatic cancer.

Five-year overall survival rates reported in previous studies ranged from 3% to 8%27, 28. Our present study showed an overall survival rate of pancreatic cancer patients of 4.2% at 5 years since diagnosis, which was within the range of previous studies. The extremely low 5-year survival rate was mainly due to the fact that a large proportion of pancreatic cancer patients had metastatic diseases at diagnosis. Additionally, the lower rate in our study might also be at least in part explained by the fact that more advanced cases were more likely to be referred to the China National Cancer for treatment.

We failed to find the association between age at diagnosis and mortality from pancreatic cancer. Women have a survival advantage over men for most cancer sites, including the pancreas29. However, we reported a decreased survival rate of female patients from pancreatic cancer (HR, 1.16; 95% CI, 1.01–1.33) compared to male patients. Age or sex may not be the substantial factor that affects survival, and these effects may vary among different studies16, 29,30,31,32. Our study suggested no significant increase in all-cause mortality for overweight and obese patients, contrary to most16, 17, 30, 33–but not all34, 35–earlier investigations. Previous reports with positive results16, 17, 30, 33 always contributed the association to two points. First, a high BMI at diagnosis could be associated with an increased frequency of perioperative and postoperative complications from pancreatic resection36 or with a lower frequency of surgery, leading to increased morbidity and mortality. However, a previous meta-analysis reported no difference in the length of hospital stay, hospital mortality, and other major outcomes between normal-weight and overweight/obese patients37. Second, insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia could be used to explain the reduced survival of overweight/obese pancreatic cancer patients, but no association between diabetes and overall survival was reported in this meta-analysis38. These two points of supporting the positive association between BMI and survival are untenable.

The major strengths of this study include its size, availability of detailed information about alcohol consumption and smoking, and availability of other data such as clinical stages, allowed for an analysis over a wide range of PDAC patients with stratification by smoking and alcohol drinking status, and clinical stages9. Despite these strengths, some study limitations should be recognized9. First, dietary information and past medical conditions (such as diabetes and chronic pancreatitis), which could affect the mortality of pancreatic cancer patients, were not considered here due to the lack of information. Second, there could be potential bias due to incomplete exposure ascertainment. However, we had only 0.5% participants missing alcohol information and 2.8% missing smoking information, suggesting the bias caused by missing information was unlikely. Third, we did not have biochemical data to evaluate their impacts. Fourth, there was no information on more detailed pathology or grading of pancreatic cancer. Finally, the absence of duration of alcohol drinking for ever drinkers and time since stopped for ex-drinkers limited the opportunity for more detailed information on the association between drinking and pancreatic cancer mortality14.

To sum up, patients who are alcohol drinkers and long-term smokers before diagnosis have a significantly higher risk of PDAC mortality. Compared to those who are neither smokers nor drinkers, only patients are both smokers and drinkers expressed reduced survival from PDAC.

References

Ferlay, J. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. International journal of cancer 136, E359–386, doi:10.1002/ijc.29210 (2015).

Lucas, A. L. et al. Global Trends in Pancreatic Cancer Mortality From 1980 Through 2013 and Predictions for 2017. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology: the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association 14, 1452–1462 e1454, doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2016.05.034 (2016).

Malvezzi, M., Bertuccio, P., Levi, F., La Vecchia, C. & Negri, E. European cancer mortality predictions for the year 2014. Annals of oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology 25, 1650–1656, doi:10.1093/annonc/mdu138 (2014).

Malvezzi, M. et al. European cancer mortality predictions for the year 2015: does lung cancer have the highest death rate in EU women? Annals of oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology 26, 779–786, doi:10.1093/annonc/mdv001 (2015).

Lee, A. T. et al. Alcohol and cigarette smoke components activate human pancreatic stellate cells: implications for the progression of chronic pancreatitis. Alcoholism, clinical and experimental research 39, 2123–2133, doi:10.1111/acer.12882 (2015).

Yu, G. P., Ostroff, J. S., Zhang, Z. F., Tang, J. & Schantz, S. P. Smoking history and cancer patient survival: a hospital cancer registry study. Cancer detection and prevention 21, 497–509 (1997).

Coughlin, S. S., Calle, E. E., Patel, A. V. & Thun, M. J. Predictors of pancreatic cancer mortality among a large cohort of United States adults. Cancer causes & control: CCC 11, 915–923 (2000).

Nakamura, K. et al. Cigarette smoking and other lifestyle factors in relation to the risk of pancreatic cancer death: a prospective cohort study in Japan. Japanese journal of clinical oncology 41, 225–231, doi:10.1093/jjco/hyq185 (2011).

Gapstur, S. M. et al. Association of alcohol intake with pancreatic cancer mortality in never smokers. Archives of internal medicine 171, 444–451, doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.536 (2011).

Pelucchi, C. et al. Smoking and body mass index and survival in pancreatic cancer patients. Pancreas 43, 47–52, doi:10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182a7c74b (2014).

The ABPI Data Sheet Compendium 1974. Drug and therapeutics bulletin 12, 43–44 (1974).

Delitto, D. et al. Nicotine Reduces Survival via Augmentation of Paracrine HGF-MET Signaling in the Pancreatic Cancer Microenvironment. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 22, 1787–1799, doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1256 (2016).

Kawaguchi, C. et al. Impact of Smoking on Pancreatic Cancer Patients Receiving Current Chemotherapy. Pancreas 44, 1155–1160, doi:10.1097/MPA.0000000000000395 (2015).

Tseng, C. H. D. insulin use, smoking, and pancreatic cancer mortality in Taiwan. Acta diabetologica 50, 879–886, doi:10.1007/s00592-013-0471-0 (2013).

Lin, Y. et al. Active and passive smoking and risk of death from pancreatic cancer: findings from the Japan Collaborative Cohort Study. Pancreatology: official journal of the International Association of Pancreatology 13, 279–284, doi:10.1016/j.pan.2013.03.015 (2013).

Olson, S. H. et al. Allergies, obesity, other risk factors and survival from pancreatic cancer. International journal of cancer 127, 2412–2419, doi:10.1002/ijc.25240 (2010).

Park, S. M., Lim, M. K., Shin, S. A. & Yun, Y. H. Impact of prediagnosis smoking, alcohol, obesity, and insulin resistance on survival in male cancer patients: National Health Insurance Corporation Study. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 24, 5017–5024, doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0243 (2006).

Dufour, M. C. & Adamson, M. D. The epidemiology of alcohol-induced pancreatitis. Pancreas 27, 286–290 (2003).

Gukovskaya, A. S. et al. Ethanol metabolism and transcription factor activation in pancreatic acinar cells in rats. Gastroenterology 122, 106–118 (2002).

Go, V. L., Gukovskaya, A. & Pandol, S. J. Alcohol and pancreatic cancer. Alcohol 35, 205–211, doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.03.010 (2005).

Talamini, R. et al. The impact of tobacco smoking and alcohol drinking on survival of patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. International journal of cancer 122, 1624–1629, doi:10.1002/ijc.23205 (2008).

Duffy, S. A. et al. Pretreatment health behaviors predict survival among patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 27, 1969–1975, doi:10.1200/JCO.2008.18.2188 (2009).

Humans, I. W. G. o. t. E. o. C. R. t. Tobacco smoke and involuntary smoking. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans 83, 1–1438 (2004).

Bosetti, C. et al. Cigarette smoking and pancreatic cancer: an analysis from the International Pancreatic Cancer Case-Control Consortium (Panc4). Annals of oncology: official journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology 23, 1880–1888, doi:10.1093/annonc/mdr541 (2012).

Ansary-Moghaddam, A. et al. The effect of modifiable risk factors on pancreatic cancer mortality in populations of the Asia-Pacific region. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention: a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 15, 2435–2440, doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0368 (2006).

Lazar, M. et al. Involvement of osteopontin in the matrix-degrading and proangiogenic changes mediated by nicotine in pancreatic cancer cells. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery: official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract 14, 1566–1577, doi:10.1007/s11605-010-1338-0 (2010).

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin 66, 7–30, doi:10.3322/caac.21332 (2016).

Fric, P. et al. Early detection of sporadic pancreatic cancer: time for change. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. doi:10.1097/MEG.0000000000000904 (2017).

Micheli, A. et al. The advantage of women in cancer survival: an analysis of EUROCARE-4 data. European journal of cancer 45, 1017–1027, doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.008 (2009).

McWilliams, R. R. et al. Obesity adversely affects survival in pancreatic cancer patients. Cancer 116, 5054–5062, doi:10.1002/cncr.25465 (2010).

Allison, D. C. et al. DNA content and other factors associated with ten-year survival after resection of pancreatic carcinoma. Journal of surgical oncology 67, 151–159 (1998).

van de Water, W. et al. Association between age at diagnosis and disease-specific mortality among postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer. Jama 307, 590–597, doi:10.1001/jama.2012.84 (2012).

Li, D. et al. Body mass index and risk, age of onset, and survival in patients with pancreatic cancer. Jama 301, 2553–2562, doi:10.1001/jama.2009.886 (2009).

Dandona, M. et al. Influence of obesity and other risk factors on survival outcomes in patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic cancer. Pancreas 40, 931–937, doi:10.1097/MPA.0b013e318215a9b1 (2011).

Gaujoux, S. et al. Impact of obesity and body fat distribution on survival after pancreaticoduodenectomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Annals of surgical oncology 19, 2908–2916, doi:10.1245/s10434-012-2301-y (2012).

Fleming, J. B. et al. Influence of obesity on cancer-related outcomes after pancreatectomy to treat pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Archives of surgery 144, 216–221, doi:10.1001/archsurg.2008.580 (2009).

Ramsey, A. M. & Martin, R. C. Body mass index and outcomes from pancreatic resection: a review and meta-analysis. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery: official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract 15, 1633–1642, doi:10.1007/s11605-011-1502-1 (2011).

Barone, B. B. et al. Long-term all-cause mortality in cancer patients with preexisting diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama 300, 2754–2764, doi:10.1001/jama.2008.824 (2008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Shuisheng Zhang: experimental design and discussion, collecting data and following up, data reduction, writing; Chengfeng Wang: experimental design and discussion, collecting data and following up, data reduction, writing; Huang Huang: experimental design and discussion, data reduction, data analysis and writing; Qinglong Jiang: experimental design and discussion, collecting data and follow-up; Dongbing Zhao: experimental design and discussion, collecting data and follow-up; Yantao Tian: experimental design and discussion, collecting data and follow-up; Jie Ma: experimental design and discussion, collecting data and follow-up; Wei Yuan: experimental design and discussion, collecting data and follow-up; Yuemin Sun: experimental design and discussion, collecting data and follow-up; Xu Che: experimental design and discussion, collecting data and follow-up; Jianwei Zhang: experimental design and discussion, collecting data and follow-up; Haibo Chen: experimental design and discussion, collecting data and follow-up; Yajie Zhao: experimental design and discussion, collecting data and follow-up; Yunmian Chu: experimental design and discussion, collecting data and follow-up; Yawei Zhang: experimental design and discussion, data reduction, data analysis and writing; Yingtai Chen: experimental design and discussion, correspondence, quality monitoring.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

Dr Chen’s work has been funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81401947), Beijing Nova Program (no. xxjh2015A090), and Cancer Hospital of the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (no. LC2015L11). Other authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, S., Wang, C., Huang, H. et al. Effects of alcohol drinking and smoking on pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma mortality: A retrospective cohort study consisting of 1783 patients. Sci Rep 7, 9572 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-08794-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-08794-1

This article is cited by

-

Impact of diabetes and modifiable risk factors on pancreatic cancer survival in a population-based study after adjusting for clinical factors

Cancer Causes & Control (2022)

-

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: biological hallmarks, current status, and future perspectives of combined modality treatment approaches

Radiation Oncology (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.