Abstract

Along with the mysteries of their ecology, freshwater eels have fascinated biologists for centuries. However, information concerning species diversity, geographic distribution, and life histories of the tropical anguillid eels in the Indo-Pacific region are highly limited. Comprehensive research on the species composition, distribution and habitat use among tropical anguillid eels in the Peninsular Malaysia were conducted for four years. A total of 463 specimens were collected in the northwestern peninsular area. The dominant species was A. bicolor bicolor constituting of 88.1% of the total eels, the second one was A. bengalensis bengalensis at 11.7%, while A. marmorata was the least abundant at 0.2%. A. bicolor bicolor was widely distributed from upstream to downstream areas of the rivers. In comparison, A. bengalensis bengalensis preferred to reside from the upstream to midstream areas with no tidal zones, cooler water temperatures and higher elevation areas. The habitat preference might be different between sites due to inter-species interactions and intra-specific plasticity to local environmental conditions. These results suggest that habitat use in the tropical anguillid eels might be more influenced by ambient environmental factors, such as salinity, temperature, elevation, river size and carrying capacity, than ecological competition, such as interspecific competition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nineteen species/subspecies of freshwater eels have been reported worldwide, 13 of which inhabit tropical regions1, 2 that are globally distributed in temperate, tropical, and subtropical areas. In tropical areas, seven species occur in the Western Pacific region around Indonesia and Malaysia1, 3, 4. The life cycle of the freshwater eel has five principal stages: leptocephalus, glass eel, elver, yellow eel and silver eel. The larvae, leptocephali, drift on ocean currents and are transported by the current. The leptocephali leave the ocean currents after metamorphosing into glass eels, and then typically migrate upstream as elvers four to eight months after hatching5 to grow in fresh water habitats during the yellow eel stage (immature stage). After the upstream migration, the elvers become yellow eels and live in fresh water habitats such as rivers and lakes. However, because individuals of several anguillid species have been found to remain in estuarine or marine habitats, it appears that not all anguillid eels enter freshwater environments; these species display more of an apparent facultative catadromy6, 7. Then, during the silver eel stage (early maturing stage) in autumn and winter, their gonads begin to mature, and they start their downstream migration back to the spawning area in the ocean where they eventually spawn and die.

In general, freshwater eels are divided into temperate and tropical eels based on their distribution range2. Molecular phylogenetic studies on freshwater eels have revealed that tropical eels are the most basal species originating in the Indonesian and Malaysian regions and that freshwater eels radiated out from the tropics to colonize the temperate regions8. This suggests that tropical freshwater eels are more closely related to the ancestral form than their temperate counterparts. Thus, studying the biological aspects of tropical eels, may provide clues for understanding the life history and nature of primitive forms of freshwater eels, and how the worldwide distribution of the anguillid eels became established.

The drastic decline in recruitment of temperate anguillid eel species (Anguilla anguilla in Europe; A. rostrata in North America; A. japonica in East Asia) in recent times has caused serious problems for maintaining sustainable levels of adult organisms9,10,11. Tropical eels are becoming the major target species for satisfying the high demand for eel products. Growing concern for many of the tropical anguillid species, particularly those inhabiting parts of the Western Central Pacific, was reflected in the assessments of species within this area12. However, very little is known about the species diversity, geographic distribution, and life histories of the many tropical eel species that are found in the Indo-Pacific region. A systematic, phylogenetic and geographical study by Ege1 has revealed that the highest diversity of Anguillidae occurs in the Indonesian and Malaysian waters. Recently, several studies have investigated spawning ecology13, 14, early life history4, 5, 15,16,17 and migration18, 19 of tropical eels in Indonesia. The findings from these studies suggest that the characteristics of both life history and ecology differ between temperate and tropical eels. The year-round spawning of the tropical species and the corresponding constant larval growth extend the period of recruitment to estuarine habitats to the whole year4, 5, 14, 17, 20. Such spawning ecology and recruitment mechanisms in tropical eels are enabled by local short-distant migrations13. For temperate eels, however, the retention of their spawning areas in the tropics requires them to migrate thousands of kilometres21 to have distinct seasonal patterns of downstream migration, spawning in the open ocean, and recruitment of glass eels.

There is relatively little information available on various aspects of the eel biology including species composition, geographic distribution, life history and migration in tropical waters. Among the tropical region, Malaysia is one of the important geographical niches of Anguillidae. Thus research on eel biology in Malaysia could provide details about their species diversity, evolutionary pathways, and life history. According to past studies, tropical eel species Anguilla bicolor bicolor, A. marmorata and A. bengalensis bengalensis have been found in Peninsular Malaysia22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. However, these studies have mainly focused on fish records, re-examination and identification of the anguillid eels. Little effort has been made to examine the species diversity, geographic distribution, habitat ecology and life history of the anguillid eels in Malaysia and Indo-Pacific region.

In the present study, comprehensive research on species diversity and geographic distribution of the anguillid eel species of Peninsular Malaysia has been done by employing accurate methods using molecular genetic analysis after conducting morphological observations. Furthermore, habitat use, segregation and preference by the tropical anguillid eels were also examined by considering environmental factors such as salinity, water temperature, tidal effects and elevation of the habitats. This study also discusses the mechanism of habitat use and segregation by sympatric species of tropical anguillid eels inhabiting a river system.

Results

Species composition in Peninsular Malaysia

A total of 408, 54 and one specimens were identified belonging to Anguilla bicolor bicolor, A. bengalensis bengalensis and A. marmorata, respectively (Table 1). The overall TL and BW in A. bicolor bicolor ranged from 203 mm to 810 mm and from 9.8 g to 1270 g, respectively (Fig. 1, Table 1). Those in A. bengalensis bengalensis ranged from 357 mm to 1295 mm and from 51.8 g to 4400 g, respectively (Table 1). TL and BW in one specimen of A. marmorata were 904 mm and 2335 g, respectively (Fig. 1, Table 1). Maturation stages of A. bicolor bicolor and A. bengalensis bengalensis were found to vary widely from Stage I (primary stage) to Stage V (final stage for spawning) (Table 1). These results suggest that the catching methods for anguillid eels in the present study would be suitable for various growth and maturation stages.

Species distribution in Penang Island and northwestern Peninsular Malaysia

Anguilla bicolor bicolor was found in 12 out of 13 sites in Penang Island (Figs 2, 3). The species was collected from upstream to downstream of each river and in both tidal and no tidal zones (Tables 2, 3). The occurrence of A. bengalensis bengalensis was restricted (8 of 13 sites) from upstream to midstream regions with no tidal zones (Tables 2, 4). Although the habitats of A. bicolor bicolor and A. bengalensis bengalensis overlapped, A. bicolor bicolor was more abundant than A. bengalensis bengalensis in many sites (Tables 3, 4, Fig. 3). A. bengalensis bengalensis was most abundant in Titi Kerawang Waterfall which is the uppermost part of the Pinang River (5; Table 4, Fig. 3). Such a trend was found in Titi Serong as well which lies upstream of Titi Teras River (10; Table 4, Fig. 3). Furthermore, the midstream of Pinang River where one A. bengalensis bengalensis was collected (Fig. 3), have higher elevations than other sites (Table 2). The area of Titi Kerawang Waterfall had the highest elevation ranging 174–217 m; the second highest elevation was in Titi Serong being 50–75 m and the third highest was in the area midstream of Pinang River being 36–38 m (Table 2). Furthermore, temperatures of these sites were lower than that in other sites. The lowest temperature was found in Titi Kerawang Waterfall ranging 23.6 to 24.2 °C and the second was Titi Serong at 25.8 °C in the midstream region of Pinang River (Table 2).

Different habitat use in freshwater ecosystem. Species composition of Anguilla bicolor bicolor and A.bengalensis bengalensis collected in the 13 sites in the Penang Island, Peninsular Malaysia. 1, Teluk Bahang in the downstream area of the Teluk Bahang River, 2, Batu Ferringhi in the downstream area of the Batu Ferringhi River, 3, Kuala Sungai Pinang in the downstream area of the Pinang River, 4, Kampung Sungai Pinang in the midstream area of the Pinang River, 5, Titi Kerawang Waterfall in the upstream area of the Pinang River, 6, Kampung Sungai Rusa in the midstream area of the Rusa River, 7, Air Putih in the midstream area of the Air Putih River, 8, Bandar Baru Air Putih in the upstream area of the Air Putih River, 9, Titi Teras in the midstream area of the Titi Teras River, 10, Titi Serong in the upstream area of the Titi Teras River, 11, Pondok Upeh in the midstream area of the Pondok Upeh River, 12, Pulau Betung in the midstream area of the Pulau Betung River, 13, Bayan Lepas in the midstream area of the Bayan Lepas River. The map was traced by the author used the Adobe Illustrator CS6 referring Google Maps 2016 (Map data ©2016 Google; https://maps.google.com/).

In Perak River, 10 specimens of A. bengalensis bengalensis were collected in Kuala Kangsar which is an upstream area with no tidal zones, but no A. bicolor bicolor was collected (Table 1, Fig. 4). Alternatively, one A. bicolor bicolor was collected in Hujung Rintis which is the estuarine part, while no A. bengalensis bengalensis was collected (Table 1, Fig. 4). In Ayer Hitam and Kampung Permatang Bongor in Penang State, which are downstream and midstream areas, only A. bicolor bicolor and no A. bengalensis bengalensis was collected (Table 1, Fig. 4).

Size distribution in Penang Island

In Penang Island, eels of various size groups were collected in each sampling site belonging to both Anguilla bicolor bicolor and A. bengalensis bengalensis species (Tables 3, 4). In Kuala Sungai Pinang, Bandar Baru Air Putih, Titi Teras and Bayan Lepas, where more than 20 A. bicolor bicolor eels were collected, two- (400 mm to 800 mm) to four-fold (200 mm to 800 mm) difference in TL were observed in a same area (Table 3). Such tendency was also observed in Titi Kerawang Waterfall in the case of A. bengalensis bengalensis where the difference in TL was approximately three-fold (i.e., 300 mm to 900 mm) (Table 4). The other sites where the sample sizes were less than 20 also had similar tendencies in that the eel sizes were variable and the eels did not fall in the same size group in each location (Tables 3, 4).

Discussion

This study is the first and the comprehensive description of the species composition, diversity, distribution and habitat use among the anguillid eels in tropical waters, which has accurate and valid species identification. Three species, Anguilla bicolor bicolor, A. bengalensis bengalensis and A. marmorata, were found to occur in the northwestern peninsular area. Overall, the dominant species was A. bicolor bicolor constituting 88.1% of the total eels, the second was A. bengalensis bengalensis at 11.7%, while A. marmorata was the least abundant at 0.2% (Table 1). Comprehensive studies by Ege1 have discussed anguillid species diversity, geographic distribution and abundance in the world and have revealed that the highest diversity of Anguillidae occurs around Indonesian and Malaysian waters. However, for Malaysia, there is relatively little information available on the various aspects of eel biology including species composition, distribution, life history and migration. Malaysia should not be excluded as a study area, as it is one of the important geographical niches of Anguillidae. Thus, eel biology research in Malaysia could provide details about their species diversity, evolutionary pathway and life history.

According to previous studies, tropical eel species Anguilla bicolor bicolor, A. bengalensis bengalensis and A. marmorata have been found in Peninsular Malaysia22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. However, these studies by Ng and Ng22, Ahmad and Lim23, Azmir and Samat24 and Hamzah et al.30 did not include comprehensive identification methods for the anguillid species. In their study, Ahmad and Lim23 had indicated that a tropical mottled eel Anguilla marmorata had been found in Peninsular Malaysia but after reexamination of a number of key characteristics of the preserved specimen, the eel was identified as A. bengalensis bengalensis instead27. The occurrence of A. bengalensis bengalensis was first recorded in Malaysian waters. Species misidentification in previous studies may have been due to insufficient data from analysis using morphological characteristics. Hence, the identification of eels at the species level using solely visual observation has been known to be difficult because of their similarities and overlapping morphological characteristics, particularly of tropical Anguillidae1, 2. In fact, the difficulty in distinguishing A. marmorata from A. bengalensis bengalensis is augmented by their overlapping morphological characteristics, which cause further identification ambiguities29. Indeed, many studies had misidentified A. marmorata by using their variegated skin only without sufficient analysis of morphological characteristics22,23,24, 30. Recently, Arai et al.28 and Arai and Wong29 have reported the first occurrence of A. bengalensis bengalensis in the Malaysian waters including the Penag and the Langkawi islands and it was confirmed by both morphological and molecular genetic analyses. Furthermore, their studies also highlighted the limitations of tropical eel species identification based solely on morphological analyses. Therefore, the previous reported A. marmorata specimens by Ng and Ng22, Ahmad and Lim23, Azmir and Samat24 and Hamzah et al.30 could have been misidentified, and may have actually been A. bengalensis bengalensis specimens. Thus, to validate the identification of the tropical eel species for further biological and ecological studies, it is crucial to utilize both morphological and molecular genetic analyses.

Anguilla bicolor bicolor and A. bengalensis bengalensis coexisted in most of habitats of Penag Island (Fig. 3), and might share the same niches, use the same demersal habitats and forage for the same prey. However, each species appears to have different habitat preference and/or habitat use. A. bicolor bicolor were able to inhabit various environments from upstream to downstream regions of rivers with preference for midstream to downstream areas. However, A. bengalensis bengalensis was restricted to midstream to upstream regions without tidal effects and was mainly found in the uppermost streams with higher elevation and cooler water. Such difference in habitat use was found in Perak River, as well, where A. bicolor bicolor was in the estuarine part and A. bengalensis bengalensis was found in the upstream area only. A. bicolor bicolor could also be found only in the downstream areas of Kedah State. These results suggest that habitat use may be a plastic response to local conditions. The area of Penang Island is 293 km2 and the rivers are much narrower and shorter than Perak River and Muda River in the Peninsular Malaysia. Therefore, both eel species may need to share their habitat in Penang Island, with less habitat partitioning. Nevertheless, the rivers in the peninsular area might have enough carrying capacity to enable the species to settle into the environmental habitats according to their preferences with regards to factors such as elevation, temperature and salinity. Interspecific competition was thought to play an important role in regulating the habitat use and population size between A. japonica and A. marmorata in Taiwan31. A. japonica is dominant in the lower reaches of the river and estuary, while A. marmorata dominates in the middle to upper reaches of the river31. These mechanisms might exist to avoid interspecific competition and attain maximum benefit for each eel species in the river. However, the distribution and habitat patterns in A. bicolor bicolor and A. bengalensis bengalensis in Penang Island did not support the interspecific competition hypothesis, but rather suggested that these species might be opportunistic in their habitat use. Recent otolith microchemical studies have found that almost all A. marmorata and A. bicolor pacifica were primarily estuarine residents occurring sympatrically in a river system in Vietnam32. The migratory patterns of A. bicolor bicolor were mainly of the switch type involving moving from freshwater to seawater environments in a lagoon in Indonesia18, 19. In contrast, the other eels resided consistently in either seawater or brackish water. No A. bicolor bicolor showed constant freshwater residence18, 19 (Table 5). Contrastingly Chino and Arai18, 19, approximately 40% A. bicolor pacifica in the Philippines showed freshwater residence, while most showed estuarine residence (60%)33. A. bicolor bicolor collected in the upper reach of complete freshwater area in Bukit Merah in Krau River of Peninsular Malaysia, was reported to have a fully freshwater life history25 (Table 5). Thus, the habitat preference might be different between sites due to inter-species interactions and intra-specific plasticity to local environmental conditions (Table 5). These results suggest that habitat use in the tropical anguillid eels might be more influenced by such ambient environmental factors as salinity, temperature, elevation, river size and carrying capacity than ecological competition, such as interspecific competition. Further studies should be undertaken to examine the environmental factors at each site with detailed distribution and migratory history analyses along the river system to elucidate the valid mechanisms of habitat use in each species.

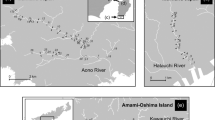

Locations where tropical anguillid eels were collected in the northwestern Peninsular Malaysia. Map showing the collection sites of tropical anguillid eels in northwestern Peninsular Malaysia between November 2012 and January 2016. The map was traced by the author using the Adobe Illustrator CS6 referring Google Maps 2016 (Map data ©2016 Google; https://maps.google.com/).

In each habitat, there was not only the coexistence of two species but also specimens of various sizes were found within the same species (Tables 3, 4). The present study suggests that minimal intraspecies competition among various growth stages might have occurred in their habitats. However, different habitat uses along the eel growth were found among temperate eels34,35,36,37,38,39,40. Such habitat preferences during the eel growth was also reported in Anguilla anguilla 34. The eels of sizes less than 160 mm had a ubiquitous behaviour. The eels of intermediate sizes between 160 mm and 360 mm showed a progressive change of habitat preference. These eels preferred deeper habitats while the large eels, more than 360 mm, had a strong preference for large ditches with deep water. The general pattern is for A. anguilla to shift progressively to deeper habitats as they grew. These results are also consistent with other studies that have found habitat shifts along the eel growth. The smaller juvenile eels of A. australis appeared to be more abundant closer to shore, but the larger eels were more evenly distributed in a lake where they may be able to use a wider range of substrate types35. Similarly, young eels of A. australis were much more abundant in the lake margins than in the open water where the larger eels predominated36. This type of habitat shift may be related to feeding, and A. australis yellow eels were found to shift to being almost exclusively piscivorous at sizes greater than 500 mm37. Eels of this size would be predominantly females. The pattern is also similar in the case A. rostrata, which become piscivorous at a size that only female eels achieve38. Although all eels are feeding generalists39, smaller eels are more restricted because of their inability to ingest larger food items such as fish. Eels do not usually undergo a dramatic niche shift, but as their size increases, so does their niche breadth as a result of the inclusion of piscivory40. Although this would be similar in A. bicolor bicolor and A. bengalensis bengalensis, this study did not find habitat shifts based on their life stages. On the other hand, temperate eels typically have quite localized home ranges with some movement to different areas. For example, studies of New Zealand eels reported that the large eels have relatively small home ranges and typically only move short distances within the streams41,42,43. Therefore, smaller eels might freely use a habitat that the bigger eels had stayed in. These results suggest that tropical eels might be able to stay in various habitats, not in an obligatory manner but facultatively during their growth and migration.

In this study, we could only observe anguillid eels in the northwestern parts of the Peninsular Malaysia. However, no eels could be observed from the southwestern to the eastern peninsular in this four year research. This pattern of geographical distribution and species composition of the anguillid eels might be due to the transportation mechanisms from spawning areas to their fresh water growth habitats in the peninsular. Recently, we discovered A. bicolor bicolor in the western and northern parts of the peninsular25. According to Jespersen44, the occurrence of preleptocephalus to metamorphosing stages in anguillid eels in waters off Sumatra supports the populations of the eels that are distributed in Java and Sumatra, and they may have their spawning area situated off the south-western coast of Sumatra, close to the distribution area of the freshwater stage (Fig. 1). Jespersen44 reported many leptocephali in the waters of west Sumatra, and 85% of the individuals ranging from 20 to 56 mm could be distinguished as the short-finned type, which were probably A. bicolor bicolor. The other 15% long-finned type would be A. bengalensis bengalensis and A. marmorata 1. The composition found near Sumatra was similar to that in northwestern Malaysia in the present study. Thus, A. bicolor bicolor, A. bengalensis bengalensis and A. marmorata in the northwestern coast of Malaysia might have originated from spawning areas from near Sumatra or the same populations. However, the distance between the spawning area and recruitment area in the southwestern and the eastern Peninsular Malaysia is considerably longer than the distance between the islands of Java and Sumatra, and there are no oceanic current transporting larvae to the eastern coast from of Sumatra45. Thus, no distribution of the anguillid eels in the eastern Sumatra supports this speculation. Further research on the spawning grounds, larval transportation and recruitment in this region are needed to gain a better understanding of the geographic distribution and ecology of the anguillid tropical eels in the eastern Indian Ocean.

Methods

Eel collection in Peninsular Malaysia

We collected the eels in Peninsula Malaysia between November 2012 and January 2016. This qualitative study was conducted mainly through interviews with local fishermen, buyers and officials and in situ samplings with local fishermen for four years. A total of 463 specimens were collected by local fishermen mainly in Penang Island (435 specimens) of the northwestern Peninsular Malaysia (Table 1, Figs 2, 4). No eels were collected from the mid-southwestern and the eastern parts of the peninsular (Fig. 4). The eels were collected by angling and with eel traps at night. All specimens were fixed immediately after collecting by freezing. The water temperature and salinity were measured sporadically at each sampling site (Table 2). No specific permission was required for these locations/activities, as the eel species involved are not endangered or protected and because the collection areas did not require any permits to collect these animals. Our protocol was in accordance with the guide for animal experimentation at Universiti Malaysia Terengganu (UMT) and fish-handling approval was granted by the animal experiment committee of UMT. Furthermore, the UMT Ethics Committee also approved all experimental protocols in this study.

Locations where tropical anguillid eels were collected in the Penang Island. Map showing the collection sites of the tropical anguillid eels in Penang Island in the northwestern Peninsular Malaysia between November 2012 and January 2016. 1, Teluk Bahang in the downstream area of the Teluk Bahang River, 2, Batu Ferringhi in the downstream area of the Batu Ferringhi River, 3, Kuala Sungai Pinang in the downstream area of the Pinang River, 4, Kampung Sungai Pinang in the midstream area of the Pinang River, 5, Titi Kerawang Waterfall in the upstream area of the Pinang River, 6, Kampung Sungai Rusa in the midstream area of the Rusa River, 7, Air Putih in the midstream area of the Air Putih River, 8, Bandar Baru Air Putih in the upstream area of the Air Putih River, 9, Titi Teras in the midstream area of the Titi Teras River, 10, Titi Serong in the upstream area of the Titi Teras River, 11, Pondok Upeh in the midstream area of the Pondok Upeh River, 12, Pulau Betung in the midstream area of the Pulau Betung River, 13, Bayan Lepas in the midstream area of the Bayan Lepas River. The map was traced by the author used the Adobe Illustrator CS6 referring Google Maps 2016 (Map data ©2016 Google; https://maps.google.com/).

Eels in Penang Island

In Penang Island, a total of 435 specimens were collected from nine rivers at thirteen sites (Figs 2, 3). Each sampling site was divided into upstream (near headwater areas without tidal influence), midstream (intermediate area of river) and downstream (less than 0.2 km from river mouth with tidal influence). These rivers are Batu Ferringhi River, Teluk Bahang River, Pinang River, Rusa River, Air Putih River, Titi Teras River, Pondok Upeh River, Pulau Betung River, and Bayan Lepas River (Fig. 2, Table 2). The four sites near the Pinang River areas were located downstream (3. Kuala Sungai Pinang), midstream (4. Kampung Sungai Pinang) and upstream (5. Titi Kerawang Waterfall) of Pinang and Rusa rivers (midstream) (Fig. 2). The four sites near Air Putih and Titi Teras rives areas include Bandar Baru Air Putih (8) (upstream) and Air Putih (7) (midstream) and Titi Serong (10) (upstream) and Titi Teras (9) (midstream) (Fig. 2). Pondok Upeh (11) is located on the midstream in the Pondok Upeh River. Sampling sites of Batu Ferringhi (2) and Teluk Bahang (1) are located in the downstream areas of each river while those of Pulau Betung (12) and Bayan Lepas (13) are located in the midstream areas (Fig. 2, Table 2). A total of 4 locations-Batu Ferringhi, Teluk Bahang, Kuala Sg. Pinang and Pulau Betung-were influenced by rising tide, while of 9 locations-TitiKerawang Waterfall, Kampung Sungai Pinang, Kampung Sungai Rusa, Bandar Baru Air Putih, Air Putih, Titi Serong, Titi Teras, Pondok Upeh and Bayan Lepas-were not influenced by the tide (Table 2).

Eels from other sites in northwestern Peninsular Malaysia

In addition to the eels collected in Penang Island, 28 of the 463 specimens were collected in Langkawi Islands (3 specimens; Arai and Wong29), Ayer Hitam (13 specimens) and Penaga (1 specimen) in Kedah State and Hujung Rintis (1 specimen) and Kuala Kangsar (10 specimens) in Perak State (Table 1, Fig. 4).

Eels of Ayer Hitam were collected in the downstream area of irrigation canals (3.7–4.8 km from estuary) where the rising tide could be influenced and controlled by the irrigation gates. The depth and elevation ranged from 0.5 m to 1.5 m and from 3 m to 5 m, respectively. One eel from Kampung Permatang Bongor was collected midstream of Muda River with no influence of the rising tide (12 km from estuary). The depth and elevation ranged from 1.9 m to 2.2 m and from 6 m to 8 m, respectively.

Perak River is the second largest river in Peninsular Malaysia with a total length of approximately 400 km. One eel from Hujung Rintis was collected downstream of Perak River (7.5 km from the river mouth) where it was influenced by the rising tide. The salinity and water temperature at the low tide and high tide ranged from 0.05‰ to 0.75‰ and from 29.9 °C to 30.5 °C, respectively. The water level varied a lot between low tide (8–9 m) and high tide (16–18 m). The elevation ranged from 0 m to 3 m. Eels from Kuala Kangsar were collected upstream of Perak River (170–176 km from the river mouth) with no influence from the rising tide, and with 0.01‰ to 0.05‰ salinity. The water temperature ranged from 28.1 °C to 36.3 °C. The depth and elevation ranged from 1 m to 13 m and from 37 m to 52 m, respectively.

Sample preparation and species identification

After the eels were collected, biological parameters, such as total length (TL) and body weight (BW), were measured (Table 1). The sex of each eel was determined by visual and histological observations of the gonads. The sex and maturation stage of all eels in Penang Island were referred from Arai and Abdul Kadir20. Maturation stages correspond to a growth phase (stages I and II), a pre-migrant phase (III) and two migrating phases (IV and V) in female. In male, maturation stages correspond to immature (stage I), early maturation (stage II) and mid-maturation (stage III) stages.

Because of the difficulty to accurately identify tropical eels solely based on morphological analyses, Arai2 suggested that accurate tropical eel species identification needed to be validate by molecular genetic analysis after morphological observation. Therefore, the anguillid eels found in the northwestern Peninsular Malaysia were first identified based on morphological analysis, and their identities were further validated by analysing the mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit I (COI) sequence and 16 S ribosomal RNA (16 S rRNA), according to Arai et al.28 and Arai and Wong29.

References

Ege, V. A revision of the Genus Anguilla Shaw. Dana Rep. 16, (8–256 (1939).

Arai, T. Taxonomy and Distribution. In Biology and Ecology of Anguillid Eels (ed. Arai, T.) 1-20 (CRC Press, 2016).

Castle, P. H. J. & Williamson, G. R. On the validity of the freshwater eel species Anguilla ancestralis Ege from Celebes. Copeia 2, 569–570 (1974).

Arai, T., Aoyama, J., Daniel, L. & Tsukamoto, K. Species composition and inshore migration of the tropical eels, Anguilla spp., recruiting to the estuary of the Poigar River, Sulawesi Island. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 188, 299–303 (1999).

Arai, T., Limbong, D., Otake, T. & Tsukamoto, K. Recruitment mechanisms of tropical eels, Anguilla spp., and implications for the evolution of oceanic migration in the genus Anguilla. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 216, 253–264 (2001).

Tsukamoto, K. & Arai, T. Facultative catadromy of the eel, Anguilla japonica, between freshwater and seawater habitats. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 220, 365–376 (2001).

Arai, T. & Chino, N. Diverse migration strategy between freshwater and seawater habitats in the freshwater eels genus Anguilla. J. Fish Biol. 81, 442–455 (2012).

Minegishi, Y. et al. Molecular phylogeny and evolution of the freshwater eels genus Anguilla based on the whole mitochondrial genome sequences. Mol. Phylogen. Evol. 34, 134–146 (2005).

Dekker, W. et al. Québec Declaration of Concern: worldwide decline of eel resources necessitates immediate action. Fisheries 28, 28–30 (2003).

Arai, T. How have spawning ground investigations of the Japanese eel Anguilla japonica contributed to the stock enhancement? Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 24, 75–88 (2014).

Arai, T. Do we protect freshwater eels or do we drive them to extinction? SpringerPlus 3, 534.

Jacoby, D. M. P. et al. Synergistic patterns of threat and the challenges facing global anguillid eel conservation. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 4, 321–333 (2015).

Arai, T. Evidence of local short-distance spawning migration of tropical freshwater eels, and implications for the evolution of freshwater eel migration. Ecol. Evol. 4(19), 3812–3819 (2014).

Arai, T., Abdul Kadir, S. R. & Chino, N. Year-round spawning by a tropical catadromous eel. Anguilla bicolor bicolor Mar. Biol. 163, 37.

Arai, T., Limbong, D., Otake, T. & Tsukamoto, K. Metamorphosis and inshore migration of tropical eels Anguilla spp. in the Indo-Pacific. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 182, 283–293 (1999).

Arai, T., Otake, T., Limbong, D. & Tsukamoto, K. Early life history and recruitment of the tropical eel Anguilla bicolor pacifica, as revealed by otolith microstructure and microchemistry. Mar. Biol. 133, 319–326 (1999).

Sugeha, H. Y., Arai, T., Miller, M. J., Limbong, D. & Tsukamoto, K. Inshore migration of the tropical eels Anguilla spp. recruiting to the Poigar River estuary on north Sulawesi Island. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 221, 233–243 (2001).

Chino, N. & Arai, T. Occurrence of marine resident tropical eel Anguilla bicolor bicolor in Indonesia. Mar. Biol. 157, 1075–1081 (2010).

Chino, N. & Arai, T. Habitat use and habitat transitions in the tropical eel. Anguilla bicolor bicolor. Environ. Biol. Fish. 89, 571–578 (2010).

Arai, T. & Abdul Kadir, S. R. Opportunistic spawning of tropical anguillid eels Anguilla bicolor bicolor and A. bengalensis bengalensis. Sci. Rep. 7, 41649 (2017).

Righton, D. et al. Empirical observations of the spawning migration of European eels: The long and dangerous road to the Sargasso Sea. Sci. Adv. 2(10), e1501694 (2016).

Ng, P. K. L. & Hg, H. P. Exploring the freshwaters of Pulau Langkawi. Nat. Malay. 14, 6–83 (1989).

Ahmad, A. & Lim, K. K. P. Inland fishes recorded from the Langkawi Islands, Peninsular Malaysia. Malay. Nat. J. 59, 103–120 (2006).

Azmir, I. A. & Samat, A. Diversity and distribution of stream fishes of Pulau Langkawi, Malaysia. Sains. Malay. 39, 869–875 (2010).

Arai, T., Chino, N., Zulkifli, S. Z. & Ismail, A. Notes on the occurrence of the tropical eel Anguilla bicolor bicolor in Peninsular Malaysia, Malaysia. J. Fish Biol. 80, 692–697 (2012).

Arai, T. & Siow, R. First documented occurrence of the giant mottled eel, Anguilla marmorata in Peninsular Malaysia, Malaysia. World Appl. Sci. J. 28, 1514–1517 (2013).

Arai, T. First record of a tropical mottled eel, Anguilla bengalensis bengalensis (Actinopterygii: Anguillidae) from the Langkawi Islands, Peninsular Malaysia, Malaysia. Mar. Biodivers. Rec. 7, e38 (2014).

Arai, T., Chin, T. C., Kwong, K. O. & Siti Azizah, M. N. Occurrence of the tropical eels, Anguilla bengalensis bengalensis and A. bicolor bicolor in Peninsular Malaysia, Malaysia and implications for the eel taxonomy. Mar. Biodivers. Rec. 8, e28 (2015).

Arai, T. & Wong, L. L. Validation of the occurrence of the tropical eels, Anguilla bengalensis bengalensis and A. bicolor bicolor at Langkawi Island in Peninsular Malaysia, Malaysia. Tropic. Ecol. 57, 23–31 (2016).

Hamzah, N. I., Khalil, N. A., Azmai, M. N. A., Ismail, A. & Zulkifli, S. Z. The distribution and biology of Indonesian short-fin eel, Anguilla bicolor bicolor and giant mottled eel, Anguilla marmorata in the northwest of Peninsular Malaysia. Malay. Nat. J. 67, 288–297 (2015).

Shiao, J. C., Iizuka, Y., Chang, C. W. & Tzeng, W. N. Disparities in habitat use and migratory behaviour between tropical eel Anguilla marmorata and temperate eel A. japonica in four Taiwanese rivers. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 261, 233–242 (2003).

Arai, T., Chino, N. & Le, D. Q. Migration and habitat use of the tropical eels Anguilla marmorata and A. bicolor pacifica in Vietnam. Aquat. Ecol. 47, 57–65 (2013).

Briones, A. A., Yambot, A. V., Shiao, J. C., Iizuka, Y. & Tzeng, W. N. Migratory pattern and habitat use of tropical eels Anguilla spp. (teleostei: Anguilliformes: Anguillidae) in the Philippines, as revealed by otolith microchemistry. Raffl. Bull. Zool. 14, 141–149 (2007).

Laffaille, P., Baisez, A., Rigaud, C. & Feunteun, E. Habitat preferences of different European eel size classes in a reclaimed marsh: a contribution to species and ecosystem conservation. Wetlands 24, 42–651 (2004).

Jellyman, D. J. & Chisnall, B. L. Habitat preferences of shortfinned eels (Anguilla australis), in two New Zealand lowland lakes. NZ J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 33, 233–248 (1999).

Chisnall, B. L. & Kalish, J. M. Age validation and movement of freshwater eels (Anguilla dieffenbachii and A. australis) in a New Zealand pastoral stream. NZ J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 27, 333–338 (1993).

Ryan, P. A. Seasonal and size-related changes in the food of the short-finned eel, Anguilla australis in Lake Ellesmere, Canterbury, New Zealand. Env. Biol. Fish. 15, 47–58 (1986).

Krueger, W. F. & Oliveira, K. Sex, size and gonad morphology of silver American eels, Anguilla rostrata. Copeia 1997, 415–420 (1997).

Helfman, G.S., Facey, D.E., Hales, L.S. & Bozeman, E.L. Reproductive ecology of the American eel. In Common strategies of anadromous and catadromous fishes. (eds Dadswell, M.J., Klauda, R.J., Moffitt, C.M., Saunders, R.L. & Rulifson, R.A. & Cooper, J.E.) Am. Fish. Soc. Symp. 1, 42–56 (1987).

Barak, N. A. E. & Mason, C. F. Population density, growth and diet of eels, Anguilla anguilla L., in two rivers in eastern England. Aquacult. Fish. Manag. 23, 59–70 (1992).

Burnet, A. M. R. The growth of New Zealand freshwater eels in three Canterbury streams. NZ J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 3, 376–384 (1969).

Chisnall, B. L. Habitat associations of juvenile shortfinned eels (Anguilla australis) in shallow Lake Waahi, New Zealand. NZ J. Mar. Freshw. Res. 30, 233–237 (1996).

Jellyman, D. J. & Sykes, J. R. E. Diel and seasonal movements of radio-tagged freshwater eels, Anguilla spp., in two New Zealand streams. Env. Biol. Fish. 66, 143–154 (2003).

Jespersen, P. Indo-Pacific leptocephali of the genus. Anguilla. Dana Rep. 22, 1–128 (1942).

Wyrtki, K. Physical oceanography of the Southeast Asian waters. NAGA Report 2. Scripps Institution of Oceanography, La Jolla, CA (1961).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Kok Onn Kwong for his assistance with the field survey. This work was supported, in part, by the Ministry of Higher Education Malaysia under the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (Vot No. 59406) and by Universiti Brunei Darussalam under the Competitive Research Grant Scheme (Vot No. UBD/OVACRI/CRGWG(003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.R.A.K. performed the field survey and the experiments described in this study. T.A. performed the field survey, supervised the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arai, T., Abdul Kadir, S.R. Diversity, distribution and different habitat use among the tropical freshwater eels of genus Anguilla . Sci Rep 7, 7593 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07837-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-07837-x

This article is cited by

-

The drivers of anguillid eel movement in lentic water bodies: a systematic map

Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries (2023)

-

A novel N95 respirator with chitosan nanoparticles: mechanical, antiviral, microbiological and cytotoxicity evaluations

Discover Nano (2023)

-

Species conservation target for freshwater fishes inhabiting Bengal sub-tropical montane rivers of Eastern Himalayas: an indexed value approach for priority determination

Aquatic Ecology (2022)

-

Migration ecology in the freshwater eels of the genus Anguilla Schrank, 1798

Tropical Ecology (2022)

-

Habitat segregation and migration in tropical anguillid eels, Anguilla bengalensis bengalensis and A. bicolor bicolor

Scientific Reports (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.