Abstract

WRKY transcription factors play important roles in plant growth development, resistance and substance metabolism regulation. However, the exact function of the response to salt stress in plants with specific WRKY transcription factors remains unclear. In this research, we isolated a new WRKY transcription factor DgWRKY5 from chrysanthemum. DgWRKY5 contains two WRKY domains of WKKYGQK and two C2H2 zinc fingers. The expression of DgWRKY5 in chrysanthemum was up-regulated under various treatments. Meanwhile, we observed higher expression levels in the leaves contrasted with other tissues. Under salt stress, the activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD) and catalase (CAT) enzymes in transgenic chrysanthemum were significantly higher than those in WT, whereas the accumulation of H2O2, O2 − and malondialdehyde (MDA) was reduced in transgenic chrysanthemum. Several parameters including root length, root length, fresh weight, chlorophyll content and leaf gas exchange parameters in transgenic chrysanthemum were much better compared with WT under salt stress. Moreover, the expression of stress-related genes DgAPX, DgCAT, DgNCED3A, DgNCED3B, DgCuZnSOD, DgP5CS, DgCSD1 and DgCSD2 was up-regulated in DgWRKY5 transgenic chrysanthemum compared with that in WT. These results suggested that DgWRKY5 could function as a positive regulator of salt stress in chrysanthemum.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Environmental stress such as cold, high salinity, metal ions, drought and other abiotic stress will severely inhibit plant growth progress, cause morphological and physiological changes, and even death. In plant stress resistance system, transcription factors regulate the expression of functional genes, which are essential for plant stress response1. Many transcription factors related to plant stress tolerance have been identified, such as DREB, bZIP, NAC, WRKY2, 3. These transcription factors combine with specific cis-acting elements to constitute a regulatory network, specifically regulate the expression of various stress-related genes, and improve the adaptability of plants to environmental stress.

WRKY transcription factors are part of the largest families of transcription factors in plants. The WRKY family was named based on the WRKY domain, which been composed of a highly conserved sequence WRKYGQK at its N-terminus with a C2H2- or C2HC-type zinc-finger motif4. And WRKY protein was divided into three groups (I, II, and III) and various subgroups were based on their original structure5. WRKY group I proteins contain two WRKY domains and two C2H2 zinc-fingers. Other studies have shown that WRKY transcription factors can specifically bind to the W box [TTGAC(C/T)], and interact with the target gene promoters6. In addition to involve in plant growth development and metabolic regulation, WRKY proteins are also resistant to stress and senescence7. Arabidopsis thaliana WRKY25, WRKY26, and WRKY33 positively regulated heat stress-response, and these three proteins interacted in function and played overlapping and synergetic roles in plant heat tolerance8. OsWRKY30 functioned as a positive regulator in rice resistance of disease via a SA signaling pathway9. Overexpression of TaWRKY2 in transgenic Arabidopsis plants enhanced tolerance to drought and salt stresses, and overexpression of wheat WRKY gene TaWRKY19 increased the salt, drought, and freezing tolerance in transgenic plants10. Moreover, overexpression of chrysanthemum genes DgWRKY1 and DgWRKY3 enhanced tolerance to salt stress in tobacco11, 12.

Chrysanthemum is a widely grown ornamental plant around the world, which is sensitive to salinity13. High salinity can cause chrysanthemum leaf chlorosis, inhibit plant growth, and sometimes even kill plants. In chrysanthemum salt tolerance experiment, we isolated and identified a novel group I WRKY transcription factor, DgWRKY5, which was demonstrated to be induced by salinity. And we found that overexpression of DgWRKY5 in chrysanthemum plants increased salt stress tolerance by regulating physiological changes and downstream genes.

Results

Isolation and characterization of DgWRKY5

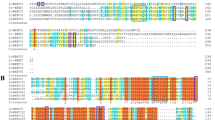

DgWRKY5 contained a complete ORF (open reading frame) of 1603bp encoding a protein of 540 amino acids with the theoretical molecular weight of 60.0KDa (Fig. S1). Multiple alignments between DgWRKY5 and the other homologous proteins via DNAMAN showed that DgWRKY5 contains two WRKY domains of WKKYGQK and two C2H2 zinc-fingers (Fig. S2). Therefore, we divided DgWRKY5 into the WRKY family group I based on the conserved domain features. The phylogenetic analysis showed that DgWRKY5 is more closely linked to AtWRKY26 from Arabidopsis thaliana (Fig. S3).

Expression analysis of DgWRKY5 under various stresses

Expression profiles of DgWRKY5 in different tissues of chrysanthemum were examined using qRT-PCR. The result showed that higher relative expression of DgWRKY5 was observed in leaves and roots, while lower relative expression was observed in stems (Fig. 1a). Expression patterns of DgWRKY5 gene in leaves under salt stress were also analyzed through qRT-PCR. For salt stress, the expression level of DgWRKY5 increased gradually after 1 hour, and reached the peak at 12 hours, thereafter DgWRKY5 expression levels decreased, but remained at a higher level opposed to untreated control (Fig. 1b). Under ABA treatment, transcript level reached a peak at 6 hours and then declined (Fig. 1c). In response to H2O2, DgWRKY5 expression was induced after 12 hours of treatment and then subsequently dropped (Fig. 1d). During GA treatment, DgWRKY5 transcript level accumulated, reaching its maximum at 3 hours and gradually diminishing (Fig. 1e). These results suggest that DgWRKY5 expression was induced under various stresses.

Analysis of DgWRKY5 expression in different tissues and in response to various treatments. (a) Expression patterns of DgWRKY5 in roots, stems and leaves. (b) Salt. (c) ABA. (d) H2O2. (e) GA. Data represent means and standard errors of three replicates. Different letters above the columns indicate significant differences (P < 0.05) on the basis of Duncan’s multiple range test.

Salt tolerance analysis of DgWRKY5 in transgenic chrysanthemum

To investigate whether overexpression of DgWRKY5 enhances salt tolerance, transgenic chrysanthemum lines overexpressing DgWRKY5 were generated, and DgWRKY5 transcription levels in eight transgenic lines were detected by qRT-PCR (Fig. S4a–c). DgWRKY5 transcription levels were substantially (P < 0.05) higher in OE-17 and OE-56 than in WT (Fig. 2a). Therefore, we selected OE-17 and OE-56 lines plants for further salt tolerance evaluation. Under normal conditions, the phenotype of transgenic plants and WT plants had no significant difference. However, leaves of WT plants were evident wilting and yellowing compared with transgenic lines OE-17 and OE-56 under salt stress (Fig. 2c,d). Two weeks recovery after salinity, the survival rate in WT was 35%, while the survival rates in transgenic lines OE-17 and OE-56 were 88% and 78%, respectively, which were two times as many as that in WT (Fig. 2b).

Salinity tolerance of transgenic chrysanthemum plants overexpressing DgWRKY5 (OE-17 and OE-56). (a) The expression level of DgWRKY5 in wild type (WT) and transgenic lines. (b) The survival rates of transgenic lines and WT after two weeks of recoveries. (c) Phenotypic comparison of DgWRKY5 transgenic lines (OE-17 and OE-56) and WT under salt stress. (d) Transgenic lines and WT grown under non-stress and salt stress conditions, followed by a recovery.

Accumulation of H2O2, O2 − and MDA in DgWRKY5 transgenic chrysanthemum plants under salt stress

In order to study salt tolerance differences between DgWRKY5 transgenic chrysanthemum (OE-17 and OE-56) and WT, H2O2, O2 − and MDA were determined. MDA is a product of membrane lipid peroxidation, which can directly reflect the degree of membrane damage. Under routine conditions, the content of H2O2, O2 − and MDA between wild-type and transgenic plants had no significant (P < 0.05) difference (Fig. 3a–c). Under salt stress, the H2O2, O2 − and MDA content of all lines increased slightly after exposed to salinity. However, the accumulation of H2O2, O2 − and MDA in transgenic lines was much smaller than WT in response to salt stress (Fig. 3a–c). To intuitively understand the oxidation status of chrysanthemum, the accumulation of H2O2 and O2 −, two major reactive oxygen species, was detected with 3, 3′-diaminovenzidine (DAB) staining and nitroblue tetazolium (NBT) staining. The consequence of research indicated that the accumulation of H2O2 and O2 - in leaves of transgenic lines was significantly (P < 0.05) lower, compared with WT plants (Fig. 3d, e). These data suggested that WT plants suffered more severe membrane damage than DgWRKY5 transgenic plants. And it indicated that overexpression of DgWRKY5 conferred transgenic chrysanthemum greater tolerance to the oxidative stress associated with salt stress.

Accumulation of osmotic regulators in DgWRKY5 transformed chrysanthemum plants under salt stress

In order to examine the effect of osmotic adjustment on the salt tolerance between WT and transgenic plants, we determined the contents of soluble protein, soluble sugar and proline in transgenic lines and wild-type plants (Fig. 4a–c). These three osmotic regulators had no significant (P < 0.05) difference between transgenic lines and wild-type plants under non-stress conditions. With the increase of salinity, the proline content of wild type and transgenic lines increased rapidly, and the accumulation in transgenic lines was significantly (P < 0.05) higher than in wild type (Fig. 4a). In addition, after 5 days of salt processing, the content of soluble protein and soluble sugar in wild-type and transgenic lines was changed rarely, then with the increase of salinity, the content of transgenic plants in the following 10 days increased by nearly twice as much as WT (Fig. 4a–c). These osmotic adjustment substances were positively correlated with the salt tolerance of plants. These results indicated that overexpression of DgWRKY5 plants increased salt tolerance by enhancing osmotic regulators.

Analysis of antioxidant enzyme activity in DgWRKY5 transformed chrysanthemum plants under salt stress

Antioxidant enzymes are the vital part in resistance of plants to stress14. So we measured the activities of SOD, POD and CAT in both WT and transgenic lines. The activities of SOD, POD and CAT in WT and transgenic plants remained the same during normal condition (Fig. 4d–f). However, with the increase of salinity, the activities of SOD, POD and CAT in transgenic plants rapidly raised and remained high levels, which were markedly (P < 0.05) higher than WT plants (Fig. 4d–f). These results suggested that salt tolerance in transgenic chrysanthemum was enhanced by the boost of antioxidant enzyme activities.

Effect of salt stress on growth, chlorophyll content and photosynthesis in DgWRKY5 transformed chrysanthemum plants

In order to study the effects of salt stress on growth and Photosynthesis of transgenic Chrysanthemum, we measured the root length, fresh weight, chlorophyll content and leaf gas exchange parameters under salt stress. Salt stress inhibited the growth and development of chrysanthemum, WT and transgenic plants both showed root atrophy and fresh weight reduction, but the root length, fresh weight of transgenic plants decreased less, compared to WT (Fig. 5a,b). As shown in Fig. 5c, under different salt concentrations, the chlorophyll increased first and then decreased, and the transgenic plants decreased slightly than WT. With the increase of NaCl concentration, the net photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance and transpiration rate of WT and transgenic plants both decreased, and the reduction range of transgenic plants was less than WT (Fig. 5d,e,g). On the contrary, intercellular CO2 concentration increased with salinity under salt stress, and the amplitude of WT was higher than that of transgenic plants (Fig. 5f). These results demonstrate that salt stress hindered the growth and photosynthesis of chrysanthemum, while the DgWRKY5 transgenic plants had stronger salt tolerance compared with WT.

Expression of abiotic stress-related genes in DgWRKY5 transformed chrysanthemum plants

To reveal the underlying regulatory mechanisms of DgWRKY5 transgenic lines in response to salinity stress, we investigated the relative expression level of eight stress-related genes through qRT-PCR, including DgAPX, DgCAT, DgNCED3A, DgNCED3B, DgCuZnSOD, DgP5CS, DgCSD1 and DgCSD2. The expression levels of these genes were no obvious difference in wild type and transgenic lines during normal conditions (Fig. 6a–h). After salt stress, relative expression level of DgAPX and DgCAT genes which encoded ROS scavenging enzymes were significantly (P < 0.05) up-regulated in DgWRKY5 transgenic lines, comparing with WT plants increased by about two and three times, respectively (Fig. 6a,b). And the expression of ABA-responsive genes DgNCED3A, DgNCED3B and DgCuZnSOD had also greatly raised in transgenic lines compared to WT under salt treatment (Fig. 6c–e). Moreover, other abiotic stress-response genes, such as DgP5CS, which functions in osmotic adjustment, DgCSD1, and DgCSD2 were all significantly (P < 0.05) increased in transgenic plants than WT under salinity condition (Fig. 6f–h). Therefore, DgWRKY5 may enhance salt tolerance of transgenic chrysanthemum by up-regulating expression levels of stress-related genes.

Expression of stress responsive genes in WT and DgWRKY5 transgenic lines (OE-17 and OE-56) at various time points (0, 1, 5, 10 and 15d). EF1a was amplified as a control. Data represent means and standard errors of three replicates. Different letters above columns indicate (P < 0.05) differences between lines.

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that WRKY transcription factors play an important role in regulating the response of plants to abiotic stress15, 16. In this research, we isolated and identified a transcription factor, DgWRKY5, from chrysanthemum. DgWRKY5 contains two WRKY domains of WKKYGQK and two C2H2 zinc-fingers in sequence analysis (Fig. S2). The phylogenetic analysis showed that DgWRKY5 is clustered with AtWRKY26 and AtWRKY25 from Arabidopsis thaliana, TaWRKY2 from Triticicum aestivum L. and OsWRKY30 from rice, all these genes belong to WRKY family group I (Fig. S3).

DgWRKY5 was significantly induced by salt stress, which is similar with AtWRKY25, AtWRKY33 in Arabidopsis thaliana and TaWRKY2 in Triticicum aestivum L 10, 17. Moreover, the DgWRKY5 transgenic chrysanthemum was more tolerant to salt stress which is similar to other WRKY transcription factors from same subgroup, including AtWRKY26, AtWRKY25, OsWRKY30 and TaWRKY2, which also strengthen transgenic plants’ resistance to abiotic stress as described in the previous section. In addition, it is possible that the same subgroup transcription factors have analogous effects on abiotic stress. In addition, DgWRKY5 is also strongly induced by multiple stresses, including ABA, H2O2 and GA. These results indicate that DgWRKY5 is a novel transcription factor of WRKY family, which may participate in response to abiotic stress.

In response to salt stress, plant cells often tend to accumulate some organic molecules, such as proline, soluble sugar and soluble protein in the cytoplasm, to maintain a high osmotic pressure and ensure the plant can be still absorb moisture from the soil. The accumulation of proline is a protective measure taken by plants in order to fight against salt stress18. And it has been reported that plants with higher proline and soluble sugar had better resistant to stress19. In our research, we found that the contents of osmotic adjustment substances in transgenic plants were noticeably higher than WT plants. These data indicated that DgWRKY5-overexpression plants may enhance the ability to withstand salt stress in plants by increasing the content of osmotic adjustment substances.

High salinity leads to reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation, which may injure cytomembrane, cause mediate lipid peroxidation and more oxidative damage in plants20. It was reported that abiotic stress can causes lipid peroxidation, leading to accumulation of MDA21. The content of MDA can reflect the degree of harm brought about by salt stress on plants22. In this experiment, DgWRKY5 transgenic plants produced a small amount of H2O2 and MDA in comparison with WT under salt stress. Protective substances include enzymes, such as SOD, POD and CAT. SOD is a primary O2 - scavenger, and CAT dismutates H2O2 into water and molecular oxygen, and POD decomposes H2O2 by oxidation of co-substrates such as phenolic compounds and/or antioxidants23. DgWRKY5 transformed chrysanthemum plants contained highly activity of ROS scavenging enzymes (SOD, POD and CAT), compared with WT under non-stress condition and salt treatment. These results suggested that DgWRKY5 could regulate the expression of ROS scavenging enzymes, enhance cell membrane protection system and weaken the membrane lipid peroxidation to improve the salt tolerance of plants.

Salt stress can cause plant growth and development to be seriously hindered, root length decreased and fresh weight reduction24. In our study, the higher the salinity was, the more inhibited the root length and fresh weight of chrysanthemum, but the inhibition of salinity was less on transgenic plants, compared with WT. Chlorophyll is the basic pigment for photosynthesis in plants, and its changes directly affect the photosynthesis of plants25. Salt stress increased chlorophyllase activity and promoted chlorophyll degradation, which caused chlorophyll content to decrease26. However, some studies have shown that salt stress can increase chlorophyll content significantly, it is considered that the binding between chlorophyll and chloroplast proteins in leaves is relaxed under salt stress, which makes chlorophyll easy to extract27. Our data revealed that DgWRKY5 transgenic plants had higher chlorophyll content than WT, and the content was both increased under 100 mM NaCl stress. Plant photosynthesis is the basic process of material accumulation and physiological metabolism in plant production process28. It is also an important means to analyze environmental affecting plant growth and metabolism. In this study, the net photosynthetic rate (Pn), stomatal conductance (Gs) and transpiration rate (Tr) decreased, while intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci) increased under high salinity stress, it showed that the photosynthetic ability of mesophyll cells was further decreased, and the utilization of CO2 was lower, leading to CO2 excess and a corresponding decrease in photosynthetic product, so plants are more seriously damaged. However, these parameters of leaf gas exchange in DgWRKY5 transgenic plants showed that it was more photosynthetic than WT and had stronger salt resistance. These results suggest that DgWRKY5 transgenic plants may be resistant to salt stress by slowing salt damage to roots and enhancing leaf photosynthesis.

Under various stresses, transcription factors play important roles by modulating the target genes expression to strengthen the ability of plants stress tolerance29. P5CS gene, as a kind of osmotic protective agent, helps the plant to resist the change of osmotic imbalance under salt stress30. CSD1 and CSD2, which are very effective on the detoxification of superoxide radicals31, 32. NCED is another important enzyme in the synthesis of ABA and has been determined to function in drought and salt stress6. In addition, CuZnSOD and APX have essential roles in enhancing the salt tolerance of sweet potato33. In this study, relative expression levels of stress responsive genes which were participated in oxidative stress-response (DgCAT and DgAPX), osmotic adjustment membrane protection (DgP5CS), and others mentioned above, were markedly up-regulated in DgWRKY5 transgenic lines compared with wild-type under salt stress. The results suggested DgWRKY5 may function as a constructive potential regulator of salt stress response pathway by controlling the expression of stress responsive genes.

In conclusion, DgWRKY5, a new WRKY transcription factor, was isolated from chrysanthemum and induced by abiotic stress. DgWRKY5-overexpression chrysanthemum showed enhanced salt tolerance compared with WT plants. In this study, we explored the physiological and molecular mechanism of DgWRKY5, and revealed that DgWRKY5 played roles as a positive regulator in salt stress-response through regulating ROS scavenging and osmotic adjustment system as well as expression levels of stress-related genes.

Methods

Plant materials and stress treatments

The experimental plant material is wild-type chrysanthemum variety “Jinba” (Dendronthema grandiform). Chrysanthemum seedlings were grown in a greenhouse at 25 °C/16 h lights, 22°C/8 h dark cycle (light intensity of 200 μmol m-2s-1; relative humidity of 70%). For salinity and ABA treatments, chrysanthemum plants at the 6–7 leaves stage were used to culture in 200 mM NaCl or in 100 μM ABA media, respectively. For the H2O2 and GA treatments, the seedings were sprayed with 10 mM H2O2 or 5 μM GA, respectively. Untreated plants were used as controls. Samples of all the treatments were harvested at 0, 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 h, frozen in liquid nitrogen promptly and stored at −80 °C for RNA extraction. For tissue-specific expression analyses, roots, stems and leaves of the same untreated seedlings were likewise collected. Each experiment contained three biological repeats.

Cloning of DgWRKY5 gene

On the basis of transcriptions data in chrysanthemum seedlings under non-stress conditions and salt stress conditions applying 454 high throughout sequencing technique, a large amount of salt-induced transcription was appraised. DgWRKY5, a novel transcription factor, was obviously brought about by salt stress. To obtain the total RNA sequence of DgWRKY5, leaves of seedlings at the 6–7 leaves stage were collected after 24 h under 400 mM NaCl treatment. Total RNA from chrysanthemum leaves was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Mylab, Beijing). The full-length cDNA of DgWRKY5 sequence was obtained by PCR (polymerase chain reaction) and utilizing the gene specific primers (Table S1).

Expression of DgWRKY5 under salt treatment

We isolated total RNA from the chrysanthemum plants under salt stress treatment using TRIzol reagent (Mylab, Beijing) according to manufacturer’s protocol. Then RNA was used for first-strand cDNA synthesis with reverse transcriptase (Transgen, Beijing) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using SsoFast EvaGreen supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and Bio-Rad CFX96TM detection system. The gene Elongation Factor 1α (EF1α) was used as a reference for quantitative expression analysis. A final 20 μL qPCR reaction mixture contained 10 uL SsoFast EvaGreen supermix, 2 uL diluted cDNA sample, and 300 nM primers. Then the reactions were incubated under the following program: 1 cycle of 95 °C for 30 s, 40 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C and 30 s at 60 °C, and a single melt cycle from 65 to 95 °C. Each reaction had repeated at least three times and negative controls without templates were detected in case of contamination. Relative expression levels were calculated by the 2−ΔΔCT method34.

Generation of DgWRKY5 transgenic Chrysanthemum plants

In order to get the generation of DgWRKY5 transgenic Chrysanthemum, DgWRKY5 full-length cDNA was inserted into the expression vector pCAMBIA 2300 under the control of CaMV (cauliflower mosaic virus) 35 S promoter by replacing the gus gene. The obtained vector was transformed into chrysanthemum at leaf disk via Agrobacterium tumefaciens (strain LBA4404) according to An et al.35. The obtained DgWRKY5 transgenic chrysanthemum lines (OE-17 and OE-56) were employed in subsequent experiments.

Salt treatment of transgenic chrysanthemum

For the salinity tolerance experiment, three-week-old WT and DgWRKY5 transgenic chrysanthemum seedlings (OE-17 and OE-56) were used. Chrysanthemum seedlings were watering with an increasing concentration of NaCl every fifth day over the following days: 100 mM on day 1–5, 200 mM on day 6–10, 400 mM on day 11–15, based on referring to the suggestion of Chen et al.36.Root length and fresh weight were measured at 0, 5, 10 and 15 days. The survival rate of the seedlings was calculated after 2 weeks recovery processes.

Physiological changes in transgenic chrysanthemum

Leaves of the above WT and transgenic plants were harvested for biochemical analysis after 0 days, 5 days and 10 days of salt treatment. Accumulation of H2O2 was assayed as described by Alexieva et al.37. Content of MDA was mensurate following the method of Zhang et al.38. Accumulation of proline was estimated according to Liu et al.39. Accumulation of soluble protein and soluble sugar was measured following Wang et al.40. Activities of SOD and POD were measured following Pan et al.41. And CAT activities were assayed following Zhang et al.42. The chlorophyll content was determined following Qin et al.43. Leaf gas exchange parameters were measured following Khaled et al.26, setting the endogenous light intensity is 600μmol·m−2·S−1, the concentration of CO2 is 360 μL·L−1, the temperature is 25 °C.

Expression of abiotic stress response genes in DgWRKY5 transgenic chrysanthemum

In order to valuate the expression of abiotic stress-related genes, the RNA of WT and transgenic lines were extracted for reverse transcription to generate cDNA as described above. Then relative expression levels of several abiotic stress-related genes in DgWRKY5 transgenic chrysanthemum were detected by qRT-PCR with EF1α served as the internal reference gene. Abiotic stress-response genes monitored were DgAPX, DgCAT, DgNCED3A, DgNCED3B, DgCuZnSOD, DgP5CS, DgCSD1 and DgCSD2. All relevant primers in the article are listed in Table S1.

References

Hennig, L. Plant gene regulation in response to abiotic stress. Biochim Biophys Acta 1819, 85–194 (2012).

Agarwal, P. K., Agarwal, P., Reddy, M. K. & Sopory, S. K. Role of DREB transcription factors in abiotic and biotic stress tolerance in plants. Plant Cell Rep. 25, 1263–1274 (2006).

Vinocur, B. & Altman, A. Recent advances in engineering plant tolerance to abiotic stress: achievements and limitations. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 16, 123–132 (2005).

Rushton, P. J., Somssich, I. E., Ringler, P. & Shen, Q. J. WRKY transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci 15, 247–258 (2010).

Eulgem, T., Rushton, P., Robatzek, S. & Somssich, I. The WRKY superfamily of plant transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 5, 199–206 (2000).

Fan, Q. Q. et al. CmWRKY15 Facilitates Alternaria tenuissima Infection of Chrysanthemum. PLoS One. 10, e0143349 (2015).

Yan, H. R. et al. The Cotton WRKY Transcription Factor GhWRKY17 Functions in Drought and Salt Stress in Transgenic Nicotiana benthamiana Through ABA Signaling and the Modulation of Reactive Oxygen Species Production. Plant Cell Physiol 55, 2060–2076 (2014).

Li, S. J., Fu, Q. T., Chen, L. G., Huang, W. D. & Yu, D. Q. Arabidopsis thaliana WRKY25, WRKY26, and WRKY33 coordinate induction of plant thermotolerance. Planta. 233, 1237–1252 (2011).

Ryu, H. S. et al. A comprehensive expression analysis of the WRKY gene superfamily in rice plants during defense response. Plant Cell Rep 25, 836–847 (2006).

Niu, C. F. et al. Wheat WRKY genes TaWRKY2 and TaWRKY19 regulate abiotic stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Plant Cell Environ 35, 1156–1170 (2012).

Liu, Q. L. et al. Functional Analysis of a Novel Chrysanthemum WRKY Transcription Factor Gene Involved in Salt Tolerance. Plant Mol Biol Rep 32, 282–289 (2014).

Liu, Q. L. et al. Overexpression of a chrysanthemum transcription factor gene, DgWRKY3, in tobacco enhances tolerance to salt stress. Plant Physiol Biochem 69, 27–33 (2013).

Liu, Q. L. et al. Overexpression of a novel chrysanthemum Cys2/His2-type zinc finger protein gene DgZFP3 confers drought tolerance in tobacco. Biotechnol Lett. 35, 1953 (2013).

Sobhanian, H., Aghaei, K. & Komatsu, S. Changes in the plant proteome resulting from salt stress: toward the creation of salt-tolerant crops? Journal of Proteomics 74, 1323 (2011).

Chen, L. G. et al. The role of WRKY transcription factors in plant abiotic stresses. Biochim Biophys Acta 1819, 120–128 (2012).

Li, J. B., Luan, Y. S. & Liu, Z. Overexpression of SpWRKY1 promotes resistance to Phytophthora nicotianae and tolerance to salt and drought stress in transgenic tobacco. Physiol Plant. 155, 248–66 (2015).

Jiang, Y. & Deyholos, M. K. Comprehensive transcriptional profiling of NaCl-stressed Arabidopsis roots reveals novel classes of responsive genes. BMC Plant Biol. 6, 25 (2006).

Ana, S. C., Manuel, A., Ana, R. & Maria, C. B. Short-term salt tolerance mechanism s in differentially salt tolerant tomato species. Plant Physiol Biochem. 37, 65–71 (1999).

Azevedo, N. et al. Effects of salt stress on plant growth, stomatal response and solute accumulation of different maize genotypes. Brazilian Journal of Plant Physiology. 16, 31–38 (2004).

Hasegawa, P. M., Bressan, R. A., Zhu, J. & Bohnert, H. J. Plant cellular and molecular responses to high salinity. Ann Rev Plant Biol. 51, 463–499 (2000).

Netondo, G. W., Onyango, J. C. & Beck, E. Sorghum and salinity: gas exchange and chlorophyll fluorescence of sorghum under salt stress. Crop Science. 44, 806–811 (2004).

RoyChoudhury, A., Roy, C. & Sengupta, D. N. Transgenic tobacco plants overexpressing the heterologous lea gene Rab16A from rice during high salt and water deficit display enhanced tolerance to salinity stress. Plant Cell Rep. 26, 1839–1859 (2007).

Yousef, S., Gholamreza, H., Weria, W., Kazem, G. G. & Khosro, M. Changes of antioxidative enzymes, lipid peroxidation and chlorophyll content in chickpea types colonized by different Glomus species under drought stress. Symbiosis. 56, 5 (2012).

Anthony, Y. Molecular biology of salt tolerance in the context of whole-plant physiology. Journal of Experimental Botany. 49, 915–929 (1998).

Strogonov, B. P. Structure and function of plant cells in saline habitats. New York:Halsted press. 78-83 (1973).

Khaled, M. et al. Responses of leaf growth and gas exchanges to salt stress during reproductive stage in wild wheat relative Aegilops geniculata Roth. and wheat (Triticum durum Desf.). Acta Physiol Plant. 35, 1453–1461 (2013).

Shao, H. B. et al. Investigation on the relationship of proline with wheat anti-drought under soil water deficits. Colloids & Surfaces B Biointerfaces. 53, 113–119 (2006).

Wu, L., Zhang, Z., Zhang, H., Wang, X. & Huang, R. Transcriptional Modulation of Ethylene Response Factor Protein JERF3 in the Oxidative Stress Response Enhances Tolerance of Tobacco Seedlings to Salt, Drought, and Freezing. Plant Physiology. 148, 1953–1963 (2008).

Chi, Y. J. et al. Protein-protein interactions in the regulation of WRKY transcription factors. Molecular plant. 6, 287–300 (2013).

Bagdi, D. L., Shaw, B. P., Sahu, B. B. & Purohit, G. K. Real time PCR expression analysis of gene encoding p5cs enzyme and proline metabolism under NaCI salinity in rice. J Environ Biol. 36, 955–961 (2015).

Kliebenstein, D. J., Monde, R. A. & Last, R. L. Superoxide dismutase in Arabidopsis: an eclectic enzyme family with disparate regulation and protein localization. Plant Physiol. 118, 637–650 (1998).

Sunkar, R., Kapoor, A. & Zhu, J. K. Posttranscriptional induction of two Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase genes in Arabidopsis is mediated by down regulation of miR398 and important for oxidative stress tolerance. Plant Cell. 18, 2051–2065 (2006).

Yan, H. et al. Overexpression of CuZnSOD and APX enhance salt stress tolerance in sweet potato. Plant Physiol Biochem. 109, 20–27 (2016).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using realtime quantitative PCR and the 2-(Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25, 402–408 (2001).

An, G., Watson, B. D. & Chang, C. C. Transformation of tobacco, tomato, potato, and Arabidopsis thaliana using a binary Ti vector system. Plant Physiol. 81, 301–305 (1988).

Chen, L. et al. The constitutive expression of Chrysanthemum dichrum ICE1 in Chrysanthemum grandiflorum improves the level of low temperature, salinity and drought tolerance. Plant Cell Rep. 31, 1747–1758 (2012).

Alexieva, V., Sergiev, I., Mapelli, S. & Karanov, E. The effect of drought and ultraviolet radiation on growth and stress markers in pea and wheat. Plant Cell.Environ. 24, 1337–1344 (2001).

Zhang, L. et al. Identification of an apoplastic protein involved in the initial phase of salt stress response in rice root by two-dimensional electrophoresis. Plant Physiol. 149, 916–928 (2009).

Liu, F., Liu, Q., Liang, X., Huang, H. & Zhang, S. Morphological, anatomical, and physiological assessment of ramie [Boehmeria Nivea (L.) Gaud.] tolerance to soil drought. Genet Resour Crop Evols. 52, 497–506 (2005).

Wang, C. et al. A wheat WRKY transcription factor TaWRKY10 confers tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses in transgenic tobacco. PLoS One. 8, e65120 (2013).

Pan, Y., Wu, L. J. & Yu, Z. L. Effect of salt and drought stress on antioxidant enzymes activities and SOD isoenzymes of liquorice (Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch). Plant Growth Regul 49, 157–165 (2006).

Zhang, L. et al. Cotton GhMPK2 is involved in multiple signaling pathways and mediates defense responses to pathogen infection and oxidative stress. FEBS J. 278, 1367–1378 (2011).

Qin, L. X. et al. Cotton GalT1 Encoding a Putative Glycosyltransferase Is Involved in Regulation of Cell Wall Pectin Biosynthesis during Plant Development. Plos One. 8, e59115 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (31201649).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.Y.L., Y.H.W. and Q.L.L. conceived and designed the experiments. Q.Y.L., Y.H.W., K.W., and Z.Y.B. performed most of the experiments. Y.Z.P., L.Z. and B.B.J. participated in the experiments. Q.Y.L., K.W., Y.H.W. analyzed the data. Q.Y.L. wrote the manuscript and Q.L.L. revised and finalized the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liang, Qy., Wu, Yh., Wang, K. et al. Chrysanthemum WRKY gene DgWRKY5 enhances tolerance to salt stress in transgenic chrysanthemum. Sci Rep 7, 4799 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05170-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-05170-x

This article is cited by

-

WRKY transcription factors: evolution, regulation, and functional diversity in plants

Protoplasma (2023)

-

Phenotypic and microarray analysis reveals salinity stress-induced oxidative tolerance in transgenic rice expressing a DEAD-box RNA helicase, OsDB10

Plant Molecular Biology (2023)

-

Overexpression of GhABF3 increases cotton(Gossypium hirsutum L.) tolerance to salt and drought

BMC Plant Biology (2022)

-

Molecular cloning and functional analysis of a Chrysanthemum vestitum GME homolog that enhances drought tolerance in transgenic tobacco

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Cloning and overexpression of PeWRKY31 from Populus × euramericana enhances salt and biological tolerance in transgenic Nicotiana

BMC Plant Biology (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.