Abstract

Bulk stable isotope analysis provides information regarding food web interactions, and has been applied to several cetacean species for the study of migration ecology. One limitation in bulk stable isotope analysis arises when a species, such as Southern hemisphere humpback whales, utilises geographically distinct food webs with differing isotopic baselines. Migrations to areas with different baselines can result in isotopic changes that mimic changes in feeding relations, leading to ambiguous food web interpretations. Here, we demonstrate the novel application of radiocarbon measurement for the resolution of such ambiguities. Radiocarbon was measured in baleen plates from humpback whales stranded in Australia between 2007 and 2013, and in skin samples collected in Australia and Antarctica from stranded and free-ranging animals. Radiocarbon measurements showed lower values for Southern Ocean feeding than for extra-Antarctic feeding in Australian waters. While the whales mostly relied on Antarctic-derived energy stores during their annual migration, there was some evidence of feeding within temperate zone waters in some individuals. This work, to our knowledge, provides the first definitive biochemical evidence for supplementary feeding by southern hemisphere humpback whales within temperate waters during migration. Further, the work contributes a powerful new tool (radiocarbon) for tracing source regions and geographical feeding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ecological tracers: isotopes

Carbon and nitrogen stable isotope measurements (δ13C and δ15N values) are routinely used to study food webs interactions in both marine and terrestrial environments. Isotope values are derived from diet and are recorded in animal tissues1, 2. In general, stable isotope (SI) values are excellent tools for the interpretation of changes in feeding locations, catabolic reactions, and for assigning the trophic level of a species1,2,3. Problematically, particularly in the case of migratory species, geographical4, 5 and temporal6, 7 isotopic gradients must be accounted for prior to these interpretations. For migrants, tissue turn-over dynamics and trophic fractionation can complicate the identification of correct feeding locations and prey intake proportions8, 9. Additionally, isotopic pools with differing origins, such as body reserves, muscle protein, and direct food intake, can have non-equal contributions to tissue formation3, 10. These problems combine in the isotopic records from Antarctic migratory species that travel between geographically distinct food webs to the North and South of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. In such migrants, energy reserves acquired from distinct feeding locations are combined, resulting in the bulk δ13C and δ15N values of long-term stores being effectively averaged. As the two different isotopic pools merge and equilibrate, using bulk SI to isolate separate feeding events is rendered more difficult.

Radiocarbon (14C) is expected to be particularly useful in these scenarios for two reasons. Firstly, in determining Δ14C, the 14C measurement is corrected for isotopic fractionation as well as the amount of decay between time of death and time of measurement11, thus allowing comparisons with other Δ14C results. As a result, unlike δ13C and δ15N values, the Δ14C values obtained are a direct reflection of a specific source, and are not affected by trophic level, productivity or the composition of the prey. Secondly, while most 14C forms naturally in the upper atmosphere through interactions of cosmic ray neutrons with nitrogen, 14C was also artificially released during the 1950’s and 1960’s thermonuclear tests. This rapid increase in atmospheric 14C content, known as the “bomb-peak”, has slowly been absorbed by the biosphere and surface oceans, transferring the anomalously high Δ14C values to surface water around the globe12. These surface Δ14C values vary both regionally and temporally13, 14. Because 14C slowly decays over time (with a half-life of 5730 years), global oceanic cycling causes deep water, isolated from atmospheric exchange for decades to centuries, to be depleted in 14C relative to surface waters15, 16. The unique overturning cells of the Southern Ocean cause older, deep water from the surrounding oceans to upwell south of the Polar Front Zone17. Consequently, Southern Ocean surface waters are more depleted in radiocarbon than temperate surface waters12, 18. Because these oceanic signals are transferred through the food web, marine wildlife restricted in their foraging to regions south of the Polar Front Zone19,20,21 also have lower Δ14C values than populations whose foraging ranges extend into temperate waters13, 22.

Radiocarbon is thus a potentially valuable tracer for studying which source regions are utilised for feeding by Southern Ocean migratory fauna. Improved understanding of the importance of feeding in the Southern Ocean should significantly contribute to our understanding of the diverse environmental challenges faced in this region. For example, Polar Skua (Stercorarius maccormicki) are known to utilise both Antarctic summer feeding and breeding grounds, as well as temperate northern latitude feeding grounds contaminated by pollutants23,24,25. Their role as biological “vectors” of contamination input into the Antarctic could benefit from the potential advantages of using radiocarbon as a tracer. Similarly, a recent increase in observations of feeding outside of the Antarctic (extra-Antarctic feeding) by Southern Hemisphere Humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae, SHHWs) may signal a change to the abundance or availability of their primary food source, Antarctic krill (Euphausia superba).

Antarctic krill is a species posed as particularly vulnerable to climate change and sea-ice loss26,27,28. Since SHHWs are understood to be Antarctic Krill obligates29, 30, instances of feeding outside of the Antarctic are anomalous and need to be investigated. Previous work by the author team on baleen bulk SI profiles baleen revealed unexpected heterogeneity in recent feeding events undertaken by stranded humpback whales from two Australian populations31. While the isotopic profiles were generally consistent with feeding on prey other than Antarctic krill, intrinsic characteristics of bulk SI analysis created uncertainties in the explicit description of those events31. In particular, clear differentiation between Antarctic feeding at a higher trophic level than Antarctic krill, and feeding outside of the Antarctic was not possible using only the bulk SI approach. The ability to robustly differentiate between extra-Antarctic feeding behaviours29, 31,32,33 as either anomalous and opportunistic events, or as a widespread, routine feeding behaviour remains a key challenge in the study of current and changing humpback whale energetic health and ecology.

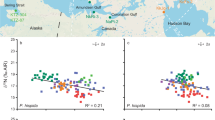

In order to provide further context to ambiguous feeding signals in bulk SI profiles of humpback whale baleen plates, a sub-sample of the plates analysed for bulk SI were selected for radiocarbon measurement. Skin samples were additionally selected to serve as short-term records of recent feeding. Radiocarbon analyses are generally expensive, so only a limited number of samples are typically analysed. We selected the samples to test the hypothesis that Δ14C would more robustly indicate geographical feeding areas than δ13C alone, and would likely co-vary with the traditional geographical feeding marker δ13C. Thus, it was expected that high values of both δ13C and Δ14C would indicate extensive feeding within temperate waters, while low values would indicate feeding within Antarctic waters. As with δ13C values, it is not expected that Δ14C will completely turn over to extra-Antarctic values as a consequence of supplementary feeding, but rather will fall on a spectrum between pure Antarctic feeding and pure extra-Antarctic feeding. Discrepancies from this pattern, such as a decoupling between δ13C and Δ14C, might occur if feeding has taken place within Antarctic upwelling waters with differing productivities34.

Results and Discussion

Radiocarbon records in baleen plates

Overall, baleen radiocarbon values grouped closely within the zone corresponding to feeding within Antarctica (Fig. 1), with few samples plotting outside this range. These results hereby support the SI findings reported previously, with most of the baleen observations belonging to the category described as “Classical Feeders” (i.e. high-fidelity feeding on Antarctic Krill, interspersed with extensive fasting31).

Temporal representation of baleen Δ14C and δ13C in baleen plates. This figure has been modified from Eisenmann, et al.31. Each horizontal zone is created using location-specific isotopic estimates consistent with prey values and trophic fractionation (if applicable). The whale isotopic data plots within the zone appropriate to provisioning location. Isotopic zones: Australian prey – merged (dotted line), Antarctic prey (dashed line).

Isotopic values for animals D01 and E10 were consistently located within the Antarctic feeding zone, with radiocarbon values constrained between −90‰ and −150‰ (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). This confirms the previous classification of these whales as Classical Feeders31.

By contrast, Δ14C values for whale D12, previously identified as a Classical Feeder31, plotted more similarly to whales E12 and E13, characterised as Supplementary Feeders31 (Fig. 1, Fig. 3). Δ14C values for these three animals were only partially located within the modern Antarctic zone, with a singular point outside the range for each individual (Fig. 1, Fig. 3). The respective trendlines between the centres of the Antarctic and Australian feeding zones are approximately Δ14C = 31* δ13C + 660. The general trendline for whales with radiocarbon values outside of the Antarctic zone was Δ14C = 25* δ13C + 500, placing Supplementary Feeders D12, E12 and E13 on the same pathway towards the Australian feeding zone (Fig. 3). A combination of Antarctic and extra-Antarctic feeding was therefore consistent with both the SI and radiocarbon patterns observed for whales E12 and E13, conclusively demonstrating extra-Antarctic feeding during migration in the recent pre-stranding life history of sampled SHHWs. The unexpected D12 results indicate that radiocarbon analysis was more sensitive than bulk δ13C analysis in detecting supplementary feeding events. While the data point was only outside our literature-defined radiocarbon boundary by ~10‰ (Table 1), this correlation between δ13C and Δ14C suggested that D12 also engaged in recent supplementary feeding during migration, although the quantities of non-Antarctic food consumed were not large enough to strongly change the bulk SI toward Australian values.

Whale E18 (Fig. 1, Fig. 3) was previously determined to be an example of a whale that remained within temperate waters in the years preceding death, with an enrichment in δ13C and δ15N over time consistent with a directional change from Antarctic feeding to Australian feeding31. Stable isotope profiles of this sort are best explained by long-term diet changes, such as partial migration in the case of the SHHWs, where the individual stays in temperate waters instead of returning to the Antarctic feeding grounds for a complete migration cycle35. This SI interpretation was further supported by the fact that whale E18 stranded in December 2012, the height of the Austral summer, when the whales are expected to be feeding in Antarctica. Radiocarbon values for this whale were consistent with its tentative classification as a Temperate Zone feeder31 (Fig. 1, Fig. 3), reaching values close to those of Australian prey species.

The combination of δ13C and Δ14C provided a robust, more powerful way to detect supplementary feeding in SHHW baleen plates than δ13C or δ15N alone. While several plausible causation factors remained following traditional SI analysis31, complementary Δ14C analysis definitively showed the high δ13C values previously measured in some SHHWs baleen plates were indicative of feeding in two different regions.

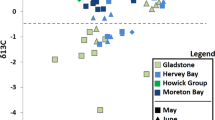

Radiocarbon records in skin

Unlike baleen plates, skin turn-over is relatively fast, and expected to fully shift to “new isotope values” in a matter of weeks. Thus, isotopic values in sampled skin should reflect Antarctic provisioning in most cases, except for recent supplementary feeders. Four out of five skin radiocarbon measurements plotted within the Antarctic feeding zone, with the fifth (E14-S) plotting close by (Fig. 4, dashed-zone). Skin samples from all three biopsied whales 13S13, 1A13, and 7A13, and from stranded whales D06 and E08 fit the radiocarbon estimates for Antarctic provisioning (Fig. 4).

Bivariate representation of skin Δ14C and δ13C. Coloured zones represent isotopic values for the Antarctic feeding grounds (gold, dashed line), and Australian feeding grounds (green, dotted line). Biopsied samples are in white, stranded individuals in black. 1A13 is not shown here due to missing δ13C data.

Baleen plates from stranded whales D06, E08 and E14 were previously analysed for SI. Whale E08 was identified as a classical feeder, while whale E14 was identified as a supplementary feeder31. In addition, baleen isotope records from neonate D06 indicated that maternal provisioning originated exclusively from Antarctic feeding grounds (Supplementary Table 2). Radiocarbon measurements for these three whales confirmed the classification that resulted from SI analysis of their baleen plates (Fig. 4). The skin sample from whale E14, however, was slightly outside the Antarctic radiocarbon range (Fig. 4). While it cannot be proven retrospectively, the particularly low δ13C values for whale E14 may, for example, be explained by an incomplete lipid extraction prior to SI analysis, particularly as they do not fit the comparatively high Δ14C values, outside of the Antarctic feeding range (Fig. 4). Productivity variations within Antarctic food webs may also potentially alter δ13C (but not Δ14C), with a wide δ13C Antarctic range already documented in SHHW baleen31. Productivity models that focus on isotope fractionation during carbon fixation predict lower δ13C values for phytoplankton areas with low productivity, and higher δ13C values for areas with high productivity36, 37. These values would be passed up the food web to consumers such as whales. Further exploration of this potential productivity response with a combination of radiocarbon and stable carbon isotopes could be important for better understanding ecosystem productivity in a time of accelerated Antarctic climate change.

As expected by the fractionation-correction applied during measurement, Δ14C did not appear to be affected by metabolism or fasting in humpback whale tissues. As such, Δ14C is in many ways a superior tracer to δ13C or δ15N for Antarctic migrating marine wildlife, since variations were directly linked to feeding in different bodies of water and not complicated by metabolic changes. This was especially visible in the skin, where samples collected in Australian and Antarctic waters showed exclusively Antarctic radiocarbon values, while the δ13C fluctuated more strongly.

In conclusion, we showed that the use of radiocarbon in Antarctic migratory biota provided an excellent, novel tracer contributing critical resolution to the traditional δ13C and δ15N tracer measurements. In this study, its use allowed us to definitively separate mixed source feeding of SH humpback whales.

Methods

Ethical Statement

Baleen plates and skin were collected from animals stranded or biopsied in Australia between 2007 and 2013. All but animal D06, a neonate, were classified as adults at the time of collection. Collection and sample details are given in Table S1. These animals belong to both the east (E1) and west (D) coast migrating populations38. Baleen and skin samples obtained from necropsied whales were preserved in scientific and museum collections until requested for analyses. In the case of the Southern Ocean Persistent Organic Pollutant Program (SOPOPP) collection, necropsy samples and biopsies were obtained under Scientific Purposes permits WISP14251214 and WISP14257414, granted by the QLD Department of Environment and Heritage Protection and Animal Ethics permit ENV1710AEC granted by the Griffith University Animal Ethics Committee, in accordance with the approved methods outlined in the permits.

Sampling and storage

Skin and baleen plates were collected from Australian stranded animals between 2007 and 2012. A further three skin biopsies were collected from free-ranging Antarctic animals during the 2012–2013 austral summer through the Southern Ocean Research Partnership Blue whale voyage. All but one of the samples were kept frozen after collection. The exception to this rule were samples from whale D01. Because the carcass from D01 was buried during decomposition, plates and tissues collected had degraded. As a result, the possible presence of soil materials on plates D01 was a concern for radiocarbon contamination.

Biopsied animals are in the form “1X11”, where the first number gives the biopsy order for the animal and the last two numbers are the year of collection. The first number restarts each season. A refers to animals sampled in Antarctica. Stranded animal IDs are in the form of “X11”, with E or D referring to the breeding population. The two numbers refer to the collection order, and are not related to sampling date.

Sample selection

No assumptions were made regarding the individual whale’s feeding behaviour prior to δ13C and δ15N SIA. For bulk SI analysis, the full length of each individual baleen plate was sampled and analysed at 1cm increments. Such increments have been showed to represent approximately 1 month of growth in baleen whales31, 39, providing an isotopic temporal record of feeding events. δ13C and δ15N baleen profiles revealed heterogeneous feeding strategies in the recent feeding history of stranded SHHWs31. While some individuals conformed to the classical model of high fidelity Antarctic Krill feeding, individual SI patterns fell on a broad spectrum spanning from high-fidelity Antarctic krill diet to complete reliance on temperate prey items. For the purpose of further analysis and discussion, the observed bulk SI profiles were divided into three categories: Classical Feeders (high-fidelity feeding on Antarctic krill interspersed with migratory fasting), Supplemental Feeders (defined here as extraneous, discrete feeding events not conforming to the classical feeding model), and Temperate Zone Feeders31. Whales D01, E10, D12, E08 and D06 were identified as belonging to the classically feeding category, with SI records consistent with low trophic level Antarctic provisioning31. In the case of neonate D06, which would not have ever fed on its own, the baleen profile indicated Antarctic-sourced maternal provisioning. As a result, D06 was classified as a classical feeder, although indirectly. Animal E18 was classed as a temperate zone feeder, with baleen records indicating a long-term, directional shift to Australian feeding. Finally, whales E12, E13, and E14 were classified as exhibiting moderate supplementary feeding at a higher trophic level and/or outside Antarctic feeding grounds31.

Radiocarbon sampling location on baleen plates from whales D01, E10, D12, E18, E12 and E13 was selected visually according to the SI profiles31 so as to provide the best coverage of interesting features in the SI records. For example, peaks and through in the profiles were selected as possible locations for shifts in feeding behaviour, and corresponding shifts in radiocarbon values. Skin samples from whales E08, D06 and E14 were selected to identify whether short-term radiocarbon values were consistent with long-term plate SI records. Two Antarctic skin biopsies were also included in the radiocarbon analyses, as well as a skin biopsy from an adult male obtained during its southward migration along the East coast of Australia in 2013. The sample from Antarctic biopsy 1A13 was insufficient to conduct subsequent bulk SI analyses.

Information regarding sample codes, feeding category and sample sources are provided in Table S1, while the full bulk SI values for each baleen plate are reported in Table S2. A subsample of values for notches analysed for both SI and radiocarbon are given in Table 1. Complete adult baleen profiles can be found in Eisenmann, et al.31, but δ13C profiles for the baleen analysed here are visible in Fig. 1.

Radiocarbon analysis

Skin samples were lipid extracted following a modified Bligh and Dyers chloroform extraction40, as used in previous work41, 42. Samples were extracted overnight using a methanol/dichloromethane (DCM)/water (MeOH/CH2Cl2/H2O) extraction (2:1:0.8 v/v/v). After addition of DCM/water (1:1:0.9 v/v/v), samples were left to partition into the aqueous and DCM phases for another day. The extracted tissue was collected and air-dried. All baleen plates were washed in deionised water, and in a 2:1 chloroform:methanol solution prior to analysis to ensure all contaminants and residual lipids were removed. Material for radiocarbon analysis was collected from the cleaned baleen plates using a rotary blade. The powdered material from D01 was further washed with 0.1M NaOH at 60 °C for 1 hour to remove soil contaminants.

Powdered baleen and skin samples were then pre-treated with 2M HCl at 60 °C for 1 hour to remove carbonates. The pre-treated material was combusted to CO2 using the sealed tube technique43 and then converted to graphite using the H2/Fe reduction43. AMS 14C measurements were carried out using the STAR 2MV Tandetron at the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO) facility44. Radiocarbon results are reported in Table 1 as percent Modern Carbon (pMC) and Δ14C (‰) as per Stuiver and Polach11. Previously measured δ13C values for all points sampled for radiocarbon analysis are also reported in Table 1 31. Unfortunately, one of the Antarctic biopsies lacked sufficient material to obtain both δ13C/δ15N and Δ14C values.

Location-specific isotopic range estimates

Location-specific isotope range estimates were necessary to infer the feeding location of the whales depending on prey items consumed. Location-specific estimates were calculated for both δ13C and Δ14C. The estimates were then used to compare whether the measured radiocarbon values matched the δ13C–inferred geographical location of feeding. For example, a whale with measured δ13C values falling within the Antarctic-specific δ13C range estimate is expected to have radiocarbon values falling within the Antarctic-specific Δ14C range estimate.

δ13C range estimates

Location-specific δ13C ranges were defined using Antarctic and Australian prey samples reported in the literature2, 45,46,47,48,49, and adjusted for trophic fractionation using a trophic estimate (TEF) appropriate for baleen tissue31 (Equation 1). The adjusted estimates are calculated as follow:

where x = sample type, p = prey, TEF is the trophic enrichment factor and SD is the standard deviation31.

The isotopic estimates include standard errors to account for temporal, taxonomic and sub-regional variability in bulk isotopes. Because it is unknown which prey type is selected by the SHHWs once they reach Australian waters, the Australian-specific range estimates were created using the outside boundaries of two previously calculated estimates. Australian krill and Australian fish estimates were therefore combined to provide one large isotopic “zone” encompassing exclusive and mixed trophic level feeding events. Similar predictions were calculated for skin tissue using the same prey data, and appropriate skin TEFs50. These are presented in Table 2.

Δ14C range estimates

Location-specific radiocarbon estimates (including error ranges) were similarly calculated using values reported in the literature (Table 3). Since radiocarbon is not influenced by trophic level, no trophic correction was applied.

When plotted in 2D space, the estimates form location-specific isotopic zones where whale samples are expected to fall depending on the type of provisioning.

References

Ben-David, M. & Flaherty, E. A. Stable isotopes in mammalian research: a beginner’s guide. Journal of Mammalogy 93, 312–328 (2012).

Cherel, Y. Isotopic niches of emperor and adélie penguins in Adélie Land, Antarctica. Marine Biology 154, 813–821 (2008).

Fry, B., Mumford, P. L. & Robblee, M. B. Stable isotope studies of pink shrimp (Farfantepenaeus duorarum Burkenroad) migrations on the southwestern Florida shelf. Bulletin of Marine Science 65, 419–430 (1999).

Jaeger, A., Lecomte, V. J., Weimerskirch, H., Richard, P. & Cherel, Y. Seabird satellite tracking validates the use of latitudinal isoscapes to depict predators’ foraging areas in the Southern Ocean. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 24, 3456–3460 (2010).

Lee, S. H., Schell, D. M., McDonald, T. L. & Richardson, W. J. Regional and seasonal feeding by bowhead whales Balaena mysticetus as indicated by stable isotope ratios. Marine Ecology Progress Series 285, 271–287 (2005).

McMahon, K. W., McCarthy, M. D., Sherwood, O. A., Larsen, T. & Guilderson, T. P. Millennial-scale plankton regime shifts in the subtropical North Pacific. Ocean. Science 350, 1530–1533 (2015).

Fleming, A. H., Clark, C. T., Calambokidis, J. & Barlow, J. Humpback whale diets respond to variance in ocean climate and ecosystem conditions in the California Current. Global Change Biology 22, 1214–1224 (2016).

Peterson, B. J. & Fry, B. Stable isotopes in ecosystem studies. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 18, 293–320 (1987).

Borrell, A., Abad-Oliva, N., Gómez-Campos, E., Giménez, J. & Aguilar, A. Discrimination of stable isotopes in fin whale tissues and application to diet assessment in cetaceans. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 26, 1596–1602 (2012).

Ayliffe, L. K. et al. Turnover of carbon isotopes in tail hair and breath CO2 of horses fed an isotopically varied diet. Oecologia 139, 11–22 (2004).

Stuiver, M. & Polach, H. A. Discussion; reporting of C-14 data. Radiocarbon 19, 355–363 (1977).

Hua, Q. Radiocarbon: a chronological tool for the recent past. Quaternary Geochronology 4, 378–390 (2009).

Druffel, E. R. M. & Griffin, S. Regional variability of surface ocean radiocarbon from Southern Great Barrier Reef corals (1995).

Druffel, E. R. M. & Griffin, S. Daily variability of dissolved inorganic radiocarbon at three sites in the surface ocean (2008).

Broecker, W. S., Gerard, R., Ewing, M. & Heezen, B. C. Natural radiocarbon in the Atlantic Ocean. Journal of Geophysical Research 65, 2903–2931 (1960).

Key, R. M. et al. A global ocean carbon climatology: results from Global Data Analysis Project (GLODAP). Glob. Biogeochem. Cycle 18, GB4031 (2004).

Rintoul, S., Hughes, C. & Olbers, D. The Antarctic circumpolar current system. In: Ocean Circulation and Climate/G. Siedler, J. Church and J. Gould, eds New York: Academic Press. p., 271–302 (2001).

Omoto, K. The problem and significance of radiocarbon geochronology in Antarctica. Antarctic Earth Science, Australian Academy of Science, Canberra 450–452 (1983).

Berkman, P. A. & Forman, S. L. Pre-bomb radiocarbon and the reservoir correction for calcareous marine species in the Southern Ocean. Geophysical Research Letters 23, 363–366 (1996).

Gordon, J. E. & Harkness, D. D. Magnitude and geographic variation of the radiocarbon content in Antarctic marine life: implications for reservoir corrections in radiocarbon dating. Quaternary Science Reviews 11, 697–708 (1992).

Michel, R. L. & Druffel, E. M. Radiocarbon in the Weddell Sea as observed in a deep-sea coral and in krill. Geophysical Research Letters 10, 190–192 (1983).

Guilderson, T. P. et al. Southwest subtropical Pacific surface water radiocarbon in a high-resolution coral record. Radiocarbon 42, 249–256 (2000).

Bustnes, J. O. et al. Organochlorines in Antarctic and Arctic Avian Top Predators: A Comparison between the South Polar Skua and Two Species of Northern Hemisphere Gulls. Environmental Science & Technology 40, 2826–2831 (2006).

Corsolini, S., Kannan, K., Imagawa, T., Focardi, S. & Giesy, J. P. Polychloronaphthalenes and other dioxin-like compounds in Arctic and Antarctic marine food webs. Environmental science & technology 36, 3490–3496 (2002).

Weimerskirch, H. et al. Population-specific wintering distributions of adult south polar skuas over three oceans. Marine Ecology Progress Series 538, 229–237 (2015).

Atkinson, A., Siegel, V., Pakhomov, E. & Rothery, P. Long-term decline in krill stock and increase in salps within the Southern Ocean. Nature 432, 100–103 (2004).

Flores, H. et al. Impact of climate change on Antarctic krill. Marine Ecology Progress Series 458, 1–19 (2012).

Kawaguchi, S. et al. Risk maps for Antarctic krill under projected Southern Ocean acidification. Nature Clim. Change 3, 843–847 (2013).

Barendse, J. et al. Migration redefined? Seasonality, movements and group composition of humpback whales Megaptera novaeangliae off the west Coast of South Africa. African Journal of Marine Science 32, 1–22 (2010).

Clapham, P. J. & Mead, J. G. Megaptera novaeangliae. Mammalian Species 1–9 (1999).

Eisenmann, P. et al. Isotopic evidence of a wide spectrum of feeding strategies in Southern Hemisphere humpback whale baleen records. PLoS ONE 11, e0156698 (2016).

D S Alves, L. C. P., Andriolo, A., Zerbini, A. N., Pizzorno, J. L. A. & Clapham, P. J. Record of feeding by humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in tropical waters off Brazil. Marine Mammal Science 25, 416–419 (2009).

Stamation, K. A., Croft, D. B., Shaughnessy, P. D. & Waples, K. A. Observations of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) feeding during their southward migration along the coast of Southeastern New South Wales, Australia: identification of a possible supplemental feeding ground. Aquatic Mammals 33, 165–174 (2007).

Seminoff, J. A. et al. Stable isotope tracking of endangered sea turtles: validation with satellite telemetry and δ15N analysis of amino acids. PLoS ONE 7 (2012).

Findlay, K. P. & Best, P. B. Summer incidence of humpback whales on the west coast of South Africa. South African Journal of Marine Science 15, 279–282 (1995).

Rau, G. H., Takahashi, T. & Des Marais, D. J. Latitudinal variations in delta 13C: implications for CO2 and productivity in past oceans. Nature 341 (1989).

Trull, T. W., Davies, D. & Casciotti, K. Insights into nutrient assimilation and export in naturally iron-fertilized waters of the Southern Ocean from nitrogen, carbon and oxygen isotopes. Deep Sea Research Part II: Topical Studies in Oceanography 55, 820–840 (2008).

Donovan, G. A review of IWC stock boundaries. Rep. Int. Whal. Comm. (Special Issue) 13, 39–68 (1991).

Best, P. B. & Schell, D. M. Stable isotopes in Southern right whale (Eubalaena australis) baleen as indicators of seasonal movements, feeding and growth. Marine Biology 124, 483–494 (1996).

Bligh, E. G. & Dyer, W. J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Canadian Journal of Biochemistry and Physiology 37, 911–917 (1959).

Waugh, C. A., Nichols, P. D., Noad, M. C. & Bengtson Nash, S. Lipid and fatty acid profiles of migrating Southern hemisphere humpback whales Megaptera novaeangliae. Marine Ecology Progress Series 471, 271–281 (2012).

Waugh, C. A., Nichols, P. D., Schlabach, M., Noad, M. & Nash, S. B. Vertical distribution of lipids, fatty acids and organochlorine contaminants in the blubber of southern hemisphere humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae). Marine environmental research 94, 24–31 (2014).

Hua, Q. et al. Progress in radiocarbon target preparation at the ANTARES AMS centre. Radiocarbon 43, 275–282 (2001).

Fink, D. et al. The ANTARES AMS facility at ANSTO. NIM B 223–224 (2004).

Davenport, S. R. & Bax, N. J. A trophic study of a marine ecosystem off Southeastern Australia using stable isotopes of carbon and nitrogen. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 59, 514–530 (2002).

Wada, E., Terazaki, M., Kabaya, Y. & Nemoto, T. 15N and 13C abundances in the Antartic Ocean with emphasis on the biogeochemical structure of the food web. Deep Sea Research Part A. Oceanographic Research Papers 34, 829–841 (1987).

Hall-Aspland, S. A., Hall, A. P. & Rogers, T. L. A new approach to the solution of the linear mixing model for a single isotope: application to the case of an opportunistic predator. Oecologia 143, 143–147 (2005).

Hodum, P. J. & Hobson, K. A. Trophic relationships among Antarctic fulmarine petrels: insights into dietary overlap and chick provisioning strategies inferred from stable-isotope (15N and 13C) analyses. Marine Ecology Progress Series 198, 273–281 (2000).

Harris, B. P., Young, J. W., Revill, A. T. & Taylor, M. D. Understanding diel-vertical feeding migrations in zooplankton using bulk carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes. J. Plankton Res. (2014).

Ryan, C. et al. Accounting for the effects of lipids in stable isotope (δ13C and δ15N values) analysis of skin and blubber of balaenopterid whales. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 26, 2745–2754 (2012).

Adamson, D. & Pickard, J. Late Quaternary ice movement across the Vestfold Hills, East Antarctica. Antarctic earth science 465, 469 (1983).

Zhang, Q., Xie, Y. & Li, Y. A preliminary study of the evolution of the post late pleistocene Vestfold Hills environment, East Antarctica. Antarctic Earth Science. Aust. Acad. Sci. Canberra 473–477 (1983).

Stuiver, M., Denton, G. H., Hughes, T. J. & Fastook, J. L. History of the marine ice sheet in West Antarctica during the last glaciation: a working hypothesis. The last great ice sheets 319–436 (1981).

Delibrias, G. C-14 in the Southern Indian Ocean. Radiocarbon 22, 684–692 (1980).

Kalish, J. M. Pre- and post-bomb radiocarbon in fish otoliths. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 114, 549–554 (1993).

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by a Pacific Life Ocean Foundation grant and a post-graduate research award (PGRA # ALNSTU11199) from the Australian Institute of Nuclear Science and Engineering (AINSE) in partnership with ANSTO. P. Eisenmann acknowledges an International and a Post-Graduate Research Scholarship from Griffith University (GUIPRS and GUPRS). Baleen plates and skin samples were sourced from collections at Griffith University, the Museum of Victoria, Murdoch University, WA, and the Tasmanian Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment (DPIPWE). The stable isotope analyses were conducted at the Stable Isotope Laboratory Griffith University by R. Diocares and R. Bak. The radiocarbon analyses were conducted at ANSTO, and we sincerely thank Fiona Doessel and Andrew Jenkinson for their help.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.E., B.F. and S.B.N. contributed to the conception and design of the experiment as well as analysis of the data. G.J. and D.M. helped design the project as well as provided laboratory and analytical tools. C.H. and D.C. provided essential samples for analysis. All authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Eisenmann, P., Fry, B., Mazumder, D. et al. Radiocarbon as a Novel Tracer of Extra-Antarctic Feeding in Southern Hemisphere Humpback Whales. Sci Rep 7, 4366 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-04698-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-04698-2

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.