Abstract

In many different cell types, pro-inflammatory agonists induce the expression of cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2), an enzyme that catalyzes rate-limiting steps in the conversion of arachidonic acid to a variety of lipid signaling molecules, including prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). PGE2 has key roles in many early inflammatory events, such as the changes of vascular function that promote or facilitate leukocyte recruitment to sites of inflammation. Depending on context, it also exerts many important anti-inflammatory effects, for example increasing the expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine interleukin 10 (IL-10), and decreasing that of the pro-inflammatory cytokine tumor necrosis factor (TNF). The tight control of both biosynthesis of, and cellular responses to, PGE2 are critical for the precise orchestration of the initiation and resolution of inflammatory responses. Here we describe evidence of a negative feedback loop, in which PGE2 augments the expression of dual specificity phosphatase 1, impairs the activity of mitogen-activated protein kinase p38, increases the activity of the mRNA-destabilizing factor tristetraprolin, and thereby inhibits the expression of COX-2. The same feedback mechanism contributes to PGE2-mediated suppression of TNF release. Engagement of the DUSP1-TTP regulatory axis by PGE2 is likely to contribute to the switch between initiation and resolution phases of inflammation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The cyclooxygenase enzymes COX-1 and COX-2, encoded by the genes Ptgs1 and Ptgs2, catalyze rate-limiting steps in the synthesis of various prostanoid signaling molecules from the lipid precursor arachidonic acid1, 2. COX-1 is constitutively expressed by many cells. In contrast, COX-2 is expressed at low levels by the majority of cells, but transiently induced in response to growth factors, stresses or pro-inflammatory stimuli. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) is the major downstream product of COX-2-mediated arachidonic acid metabolism in many cells. PGE2 increases blood flow, vascular permeability and nociception, thereby contributing to all four of the cardinal signs of inflammation; redness, swelling, heat and pain. The pro-inflammatory actions of PGE2 underlie the clinical usefulness of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which inhibit both COX-1 and COX-22. However, constitutive COX-1-mediated prostaglandin synthesis in the gastric mucosa helps to maintain the integrity of this vulnerable tissue1, which accounts for the increased incidence of gastric ulcers amongst patients using NSAIDs for prolonged periods. The rationale for the generation of COX-2-selective inhibitors was based on the assumption that COX-1 functions principally as a homeostatic enzyme, whereas COX-2 functions principally as a pro-inflammatory mediator. Selective inhibitors of COX-2 were predicted to exert anti-inflammatory effects whilst sparing gastric side effects3.

As we are reminded by the costly failure of the COX-2-selective inhibitor Rofecoxib (Vioxx), biology is rarely so straightforward or convenient4. COX-1-dependent synthesis of thromboxane by platelets promotes vasoconstriction and platelet aggregation. These prothrombotic actions are opposed by prostaglandin I2 (prostacyclin). The significantly increased risk of myocardial infarction and stroke in patients taking Vioxx eventually led to the withdrawal of this drug from the market. The basis of elevated cardiovascular risk is still not fully understood, but has been ascribed to an imbalance between COX-1-mediated pro-thrombotic and COX-2 mediated anti-thrombotic influences. Another confounding aspect of prostaglandin biology is that the actions of PGE2 are not invariably pro-inflammatory; nor are the effects of COX-2-selective inhibitors invariably anti-inflammatory. PGE2 has been shown to enhance expression of IL-10, inhibit the expression of TNF and other inflammatory mediators, and promote the differentiation of macrophages towards an alternatively-activated, anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype5,6,7,8,9,10. In rheumatoid synovial explant cultures or peripheral blood-derived monocytes, NSAIDs increased the expression of TNF11. Prior in vivo exposure to COX-2-selective inhibitors also primed human peripheral blood monocytes and mouse peritoneal macrophages for increased expression of TNF in response to an LPS challenge11, 12.

Cellular responses to PGE2 are mediated by four G protein-coupled receptors named EP1-EP4, which are the products of the genes Ptger1-Ptger4 13, 14. These receptors differ in their affinity for PGE2 and in the signal transduction pathways that they engage. Both EP2 and EP4 are Gαs-linked and activate adenylyl cyclase to elevate intracellular cAMP levels. EP4 has additionally been shown to signal via PI3K. EP1, which is coupled to Gαq, signals via phospholipase C to induce calcium flux. EP3 exists in a number of distinct forms arising from differential splicing of the Ptger3 transcript, and appears to be promiscuous in terms of its signaling pathway engagement. There is clear potential for cell-specific programing of responses to PGE2 via modulation of the expression of the four receptors or their variants. Anti-inflammatory actions of PGE2 have generally been ascribed to EP4 and/or EP25, 6, 15,16,17, however molecular mechanisms remain unclear. The increased expression of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 does not provide an explanation, as PGE2 can still inhibit macrophage expression of TNF in the absence of IL-1018, 19.

The inflammation-induced biosynthesis of PGE2 is regulated largely at the level of Ptgs2 gene expression. The typical transient pattern of expression of Ptgs2 mRNA is only partly explained by transcriptional activation involving nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and other transcription factors20. Efficient expression also requires the stabilization of Ptgs2 mRNA via the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) p38 signaling pathway, and conversely, MAPK p38 inhibitors accelerate the degradation of Ptgs2 mRNA21, 22. This post-transcriptional regulation is mediated by an adenosine/uridine-rich element (ARE) immediately 3′ to the Ptgs2 translation termination codon. When inserted into a stable reporter mRNA, the Ptgs2 ARE confers rapid decay that is mediated by shortening of the protective poly-(A) tail (deadenylation), and can be prevented by activation of MAPK p3823,24,25. This sequence element is therefore similar to MAPK p38-responsive mRNA destabilizing elements present in pro-inflammatory mRNAs such as Tnf, Csf2, Cxcl1, Il6 and many others26.

The mouse Zfp36 gene enodes the ARE-binding protein tristetraprolin (TTP)27, 28. In Zfp36−/− macrophages lacking TTP protein, Ptgs2 mRNA was highly stable and could not be destabilized by a MAPK p38 inhibitor29. TTP binds to AREs in the 3′ untranslated regions of target transcripts and recruits a complex of deadenylase enzymes, which catalyzes shortening of the poly-(A) tail, usually as a prelude to the rapid destruction of the mRNA body. The mRNA-destabilizing activity of TTP is regulated by a phosphorylation switch30. Pro-inflammatory agonists and cell stresses activate MAPK p38, which in turn phosphorylates and activates MK2 (MAPK-activated protein kinase 2). MK2 phosphorylates serines 52 and 178 of TTP, resulting in the recruitment of 14–3–3 adaptor proteins, impairment of the interaction between TTP and the deadenylase complex, and consequent stabilization of target mRNAs31,32,33. Protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) catalyzes the removal of these two phosphate groups and the activation of TTP. Therefore a dynamic equilibrium exists between forms of TTP that are phosphorylated or unphosphorylated at serines 52 and 178, and this equilibrium favors the stabilization of TTP-regulated mRNAs under conditions of strong MAPK p38 activity. Coupling between MAPK p38 activity and the stability of pro-inflammatory mRNAs contributes to the precise orchestration of the on and off phases of inflammatory responses34,35,36.

The activity of MAPK p38, and hence the phosphorylation state of TTP, is regulated by a negative feedback loop involving dual specificity phosphatase 1 (DUSP1)37. Pro-inflammatory stimuli induce MAPK p38-dependent expression of DUSP1, which then dephosphorylates and inactivates MAPK p38 to enforce the off-phase of the inflammatory response. Due to the failure of this feedback mechanism, Dusp1−/− mice and cells are prone to respond excessively to pro-inflammatory agonists, and over-express many inflammatory mediators, including COX-238, 39. The over-expression of COX-2 by Dusp1−/− macrophages is not fully understood; both transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms have been proposed40, 41. Here, we investigate the functional relationship between DUSP1, MAPK p38, TTP and COX-2. First, we use a number of genetically modified mouse strains to demonstrate that DUSP1 and MAPK p38 control the expression of COX-2 by regulating the phosphorylation of TTP at serines 52 and 178. Next we turn to the effect on macrophages of the major COX-2 product, PGE2. We show that PGE2 enhances the expression of DUSP1 and thereby downregulates the expression of COX-2, creating another auto-regulatory feedback mechanism. PGE2 also acts via the receptor EP4 to inhibit macrophage expression of TNF, in a manner that is at least partially dependent on both DUSP1 and the modulation of TTP’s phosphorylation state. Despite being an authentic TTP target, IL-6 escapes negative regulation by PGE2. The influence of PGE2 on Dusp1 gene expression creates a potent mechanism for context-dependent and gene-specific modulation of inflammatory responses.

Results

Ptgs2 gene expression is negatively regulated by TTP

A previous publication described high resolution mapping of TTP binding sites in the mouse macrophage transcriptome35. Publicly accessible data from this study (http://ttp-atlas.univie.ac.at) revealed strong binding of TTP to the 3′ UTR of Ptgs2 mRNA, which was restricted to a region immediately downstream of the open reading frame, containing a cluster of six AUUUA motifs (Fig. 1a). This region mediated regulation of Ptgs2 mRNA stability by the MAPK p38 signaling pathway, and was recognized by TTP in vitro 24, 25. Other putative TTP binding sites in the Ptgs2 3′ UTR42 appear to be recognized by TTP poorly or not at all in mouse macrophages. RNA immunoprecipitation experiments confirmed binding of TTP to Ptgs2 mRNA in the mouse macrophage cell line RAW264.7 (Fig. 1b). We recently used homologous recombination to generate a novel mouse strain (known as Zfp36aa/aa), in which serines 52 and 178 of endogenous TTP protein were substituted by non-phosphorylatable alanine residues43. The mutant form of TTP could not be inactivated by MK2-mediated phosphorylation, and functioned as a constitutive mRNA destabilizing factor, decreasing the expression of several inflammatory mediators in vitro and in vivo. Zfp36aa/aa mice were strongly resistant to experimental endotoxemia and arthritis43, 44. Zfp36aa/aa bone marrow macrophages (BMMs) under-expressed Ptgs2 mRNA at a steady-state level (Fig. 1c), particularly at later time points. The decrease in steady-state Ptgs2 expression was accompanied by an increase in its rate of degradation (Fig. 1d). COX-2 protein was expressed at low levels in LPS-treated Zfp36aa/aa BMMs (Fig. 1e). The LPS-induced release of PGE2 was significantly diminished in Zfp36aa/aa BMMs (Fig. 1f). Heterozygous Zfp36+/aa BMMs also under-expressed COX-2 protein (Supplemental Figure 1), consistent with our previous description of the non-phosphorylatable TTP mutant as a dominant inhibitor of inflammatory gene expression43. These findings confirm that Ptgs2 mRNA is an authentic, direct target of negative regulation by TTP.

Ptgs2 gene expression is negatively regulated by tristetraprolin. (a) Number of TTP crosslinks (CL) is plotted against position on the Ptgs2 primary transcript. The primary transcript is illustrated below the graph, with coding exonic sequences as grey bars and non-coding exonic sequences as black bars. Positions of AUUUA motifs are represented above the transcript, and the sequence immediately 3′ to the stop codon is expanded below. Figure adapted from TTP-atlas data (http://ttp-atlas.univie.ac.at)35. (b) RNA immunoprecipitation was performed on whole cell lysates of RAW264.7 cells, untreated or stimulated with LPS for 2 h, using a TTP antiserum or pre-immune control (PI). Gapdh, Tnf and Ptgs2 mRNAs were measured by quantitiative PCR, and fold enrichment was calculated relative to the PI control. A representative of three similar experiments is shown. Error bars indicate SD of triplicate measurements. (c) Zfp36+/+ and Zfp36aa/aa BMMs were stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS for the times indicated, and Ptgs2 mRNA was measured by qPCR. The graph represents mean ± SEM of three independent BMM cultures of each genotype. ***p < 0.005; Holm-Sidak method for multiple comparison. (d) Zfp36+/+ and Zfp36aa/aa BMMs were stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS for 4 h then actinomycin D was added and Ptgs2 mRNA measured by qPCR at the intervals indicated. The graph shows mean ± SEM of three independent BMM cultures of each genotype. (e) Zfp36+/+ and Zfp36aa/aa BMMs were stimulated with LPS for the times indicated and COX-2 protein was detected by western blotting. Representative of three repeats. (f) Zfp36+/+ and Zfp36aa/aa BMMs were stimulated with LPS for the times indicated and PGE2 in the tissue culture supernatant was measured by ELISA. The graph represents mean ± SEM of three independent BMM cultures of each genotype. ***p < 0.005; Holm-Sidak method for multiple comparison.

DUSP1 regulates Ptgs2 gene expression by modulating TTP phosphorylation

Steady state levels of Ptgs2 mRNA were elevated in LPS-treated Dusp1−/− BMMs compared with identically treated Dusp1+/+ controls (Fig. 2a), accompanied by an increase in Ptgs2 mRNA stability (Fig. 2b). The expression of COX-2 protein was increased in LPS-treated Dusp1−/− BMMs (Fig. 2c), as was the release of PGE2 (Fig. 2d). We hypothesized that deletion of the Dusp1 gene increases the expression of Ptgs2 via enhanced phosphorylation and inactivation of TTP. To test this hypothesis, expression of Ptgs2 mRNA, COX-2 protein and PGE2 was compared in wild type, Dusp1−/−, Zfp36aa/aa and Dusp1−/−: Zfp36aa/aa BMMs. At 1 h, Dusp1 gene disruption increased the expression of Ptgs2 mRNA, but targeted mutation of the Zfp36 locus was without effect (Fig. 3a). At 4 h, Ptgs2 mRNA continued to be over-expressed by Dusp1−/− BMMs, but in contrast was under-expressed by Zfp36aa/aa BMMs. Most importantly, Dusp1−/−: Zfp36aa/aa BMMs also under-expressed Ptgs2 mRNA at 4 h. A similar pattern was observed at the level of COX-2 protein (Fig. 3b) and PGE2 biosynthesis (Fig. 3c). To investigate whether the same mechanism was relevant in vivo, mice of the same four genotypes were challenged by intraperitoneal injection of LPS, and three hours later Ptgs2 mRNA expression was measured in spleen, an organ which plays a critical role in systemic responses to endotoxin (Fig. 3c). The LPS challenge strongly enhanced splenic Ptgs2 expression in mice of all four genotypes. Higher Ptgs2 expression was seen in Dusp1−/− than in wild type control mice, but significantly lower expression was seen in both Zfp36aa/aa and Dusp1−/−: Zfp36aa/aa mice. Therefore, both in vitro and in vivo, disruption of the Dusp1 gene and dysregulation of MAPK signaling enhances Ptgs2 gene expression in a manner dependent on the phosphorylation of TTP at serines 52 and 178.

DUSP1 negatively regulates Ptgs2 gene expression at the post-transcriptional level. (a) Dusp1+/+ and Dusp1−/− BMMs were stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS for the times indicated and Ptgs2 mRNA was measured by qPCR. The graph represents mean ± SEM of three independent BMM cultures of each genotype. ***p < 0.005; Holm-Sidak method for multiple comparison. (b) Dusp1+/+ and Dusp1−/− BMMs were stimulated with LPS for 4 h then actinomycin D was added and Ptgs2 mRNA measured by qPCR at the intervals indicated. The graph shows mean ± SEM of three independent BMM cultures of each genotype. (c) Dusp1+/+ and Dusp1−/− BMMs were stimulated with LPS for the times indicated and COX-2 protein was detected by western blotting. Representative of three similar experiments. (d) Dusp1+/+ and Dusp1−/− BMMs were stimulated with LPS for the times indicated and PGE2 in the tissue culture supernatant was measured by ELISA. The graph represents mean ± SEM of three independent BMM cultures of each genotype. ***p < 0.005; Holm-Sidak method for multiple comparison.

DUSP1 regulates Ptgs2 gene expression via the modulation of TTP phosphorylation. (a) Wild type, Zfp36aa/aa, Dusp1−/− and Zfp36aa/aa: Dusp1−/− BMMs were treated with 10 ng/ml LPS for 0, 1 or 4 h, and Ptgs2 mRNA was quantified by microarray. The graph shows RMA (robust multi-array average) units ± SEM from three independent BMM cultures of each genotype. The array was described and extensively validated elsewhere37. n.s., not statistically significant. ***p < 0.005, ANOVA. (b) BMMs of the same four genotypes were stimulated with LPS for 0, 4 or 8 h, and COX-2 protein was detected by western blotting. Representative of two repeat experiments. (c) BMMs of the same four genotypes were stimulated with LPS for 0 or 4 h and PGE2 in tissue culture supernatants was measured by ELISA. The graph represents mean ± SEM of three independent BMM cultures of each genotype. n.s., not statistically significant; ***p < 0.005, ANOVA. (c) Mice of the same four genotypes were injected intraperitoneally with PBS (n = 2 of each genotype) or 5 mg/kg LPS (n = 4 of each genotype). After 3 h spleens were excised, mRNA isolated, and Ptgs2 mRNA quantified by RT-PCR with normalization first against B2m RNA then against PBS-treated control (Dusp1+/+: Zfp36+/+) control mice. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.005, ANOVA.

PGE2 modulates the phosphorylation of MAPK p38, the expression of DUSP1, COX-2, TNF and IL-6

We have performed two independent microarray experiments in primary mouse BMMs and one in primary human monocyte-derived macrophages, investigating LPS-induced changes of gene expression. The first mouse microarray experiment has been described37 and deposited at the Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE68449), whilst the others are being prepared for submission. All three arrays have been extensively validated. According to all three experiments, both mouse and human primary macrophages expressed mRNAs encoding the prostaglandin receptors EP2 and EP4, whereas mRNAs encoding the other two members of this receptor family, EP1 and EP3, were essentially undetectable (Fig. 4a,b). In macrophages of both species, expression of Ptger4/PTGER4 mRNA was increased by LPS, whereas expression of Ptger2/PTGER2 mRNA was decreased or unaffected. Expression of EP4 in BMMs was confirmed by flow cytometry (Fig. 4c), whilst EP2 protein could not be detected using available reagents. LPS induced a modest increase of EP4 protein levels, which was statistically significant at 2 h (Fig. 4c,d).

Exogenous PGE2 modulates Dusp1 gene expression and MAPK p38 signaling. Expression of the mouse prostaglandin receptor genes Ptger1–4 (a) or the corresponding human genes PTGER 1–4 (b) was measured by microarray as described in Fig. 3. Graphs represent RMA ± SEM from three independent mouse or human macrophage cultures. n.s., not significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.005; ANOVA. (c) Representative flow cytometry of EP4 expression in BMMs treated with LPS for 0 or 4 h. (d) MFI of EP4 expression was measured at the indicated times after stimulation of BMMs with 10 ng/ml LPS. The graph represents mean ± SEM of three independent wild type BMM cultures. *p < 0.05; ANOVA. (e) BMMs were treated for the indicated times with LPS (10 ng/ml), PGE2 (1 nM) or both. Dusp1 mRNA was measured by qPCR, and plotted as fold increase compared to untreated controls. The graph shows mean fold increase ± SEM from three independent BMM cultures. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.005; ANOVA. (f) Primary human monocyte-derived macrophages were treated, and DUSP1 mRNA was measured, as in (e). ***p < 0.005; ANOVA. (g) Dusp1+/+ and Dusp1−/− BMMs were treated with LPS (10 ng/ml) with or without PGE2 (1 nM) for the times indicated. DUSP1, phospho-p38, COX-2 and β-actin proteins were detected by western blotting. Representative of four experimental repeats.

Although PGE2 is commonly thought of as a pro-inflammatory signaling molecule2, it is also known to exert anti-inflammatory effects in myeloid and other cells via activation of the cAMP pathway by EP2 and/or EP46, 16, 17, 45. Expression of the Dusp1 gene is regulated by cAMP via CREB binding sites in the proximal promoter46,47,48,49,50. Induction of DUSP1 expression by PGE2 was recently demonstrated in airway smooth muscle cells51. We therefore investigated whether PGE2 could modulate the expression of DUSP1 and the activity of MAPK signaling pathways in BMMs. On its own, PGE2 weakly increased the expression of Dusp1 mRNA in BMMs (Fig. 4e), although we were not able to detect PGE2-induced DUSP1 protein or changes in MAPK p38 phosphorylation. LPS rapidly and transiently increased Dusp1 mRNA. Combined treatment with LPS and PGE2 resulted in cooperative enhancement of Dusp1 mRNA levels, particularly at the peak of expression, 1 h after the stimulus. Very similar cooperative regulation of DUSP1 mRNA by LPS and PGE2 was observed in primary human monocyte-derived macrophages (Fig. 4f).

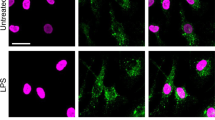

In Dusp1+/+ BMMs the LPS-induced expression of DUSP1 protein was transient, but was sustained by addition of PGE2 (Fig. 4g). The specificity of the antibody is confirmed by the failure to detect corresponding bands in Dusp1−/− BMMs. In parallel with prolonged expression of DUSP1, the inactivation of MAPK p38 was accelerated by PGE2. In three independent experiments PGE2 decreased LPS-induced MAPK p38 phosphorylation by a factor of 0.48 ± 0.06 and increased DUSP1 levels by a factor of 1.80 ± 0.26 (mean fold changes ± SEM) at the 2 h time point. At the 4 h time point phosphorylated MAPK p38 was readily detected in BMMs treated with LPS alone but not in those treated with LPS + PGE2. LPS-induced expression of COX-2 protein was also inhibited by addition of PGE2. In Dusp1−/− BMMs, the activation of MAPK p38 in response to LPS was prolonged and the expression of COX-2 protein was enhanced. Neither of these responses was affected by addition of PGE2. Hence the expression of COX-2 is regulated by a negative feedback loop that is mediated by its major catalytic product PGE2 and dependent on the expression of DUSP1.

In both Dusp1+/+ and Dusp1−/− BMMs, exogenous PGE2 inhibited the expression of TNF (Fig. 5a). These inhibitory effects were statistically significant at 4 and 8 h after the addition of LPS, and greater in magnitude in Dusp1+/+ than Dusp1−/− BMMs. Differential sensitivity of Dusp1+/+ and Dusp1−/− BMMs to anti-inflammatory effects of PGE2 was confirmed in dose-response experiments (Fig. 5b). The anti-inflammatory effect was selective, since the expression of IL-6 was not decreased by PGE2 in Dusp1+/+ macrophages (Fig. 5c). In Dusp1−/− BMMs, IL-6 expression was increased by the highest concentration of PGE2. Zfp36aa/aa BMMs were relatively insensitive to inhibitory effects of PGE2 on the release of TNF (Fig. 5d), confirming that PGE2 modulates TNF expression in part by influencing the phosphorylation of TTP. A selective antagonist of EP2 did not influence the inhibition of TNF biosynthesis by PGE2 (Fig. 5e, columns 4–7). A selective EP4 antagonist dose-dependently reversed the suppression of TNF expression by exogenous PGE2 (Fig. 5e, columns 8–11) but did not, on its own, increase TNF production (Fig. 5e, column 12). This suggests that EP4 is the major mediator of the anti-inflammatory effects of PGE2 in this context.

Anti-inflammatory effects of PGE2 are gene-selective and partially dependent on DUSP1. (a) Dusp1+/+ and Dusp1−/− BMMs were treated with 10 ng/ml LPS for the indicated times in the absence or presence of 1 nM PGE2, and TNF was measured by ELISA. The graph shows mean ± SEM of three independent BMM cultures of each genotype. The numbers above the graph indicate percentage inhibition of TNF release by PGE2. ***p < 0.005; Holm-Sidak method for multiple comparison. (b) Dusp1+/+ and Dusp1−/− BMMs were treated with 10 ng/ml LPS for 4 h in the presence of increasing concentrations of PGE2, and TNF was measured by ELISA. The graph on the left illustrates absolute quantities of TNF. In the right hand graph, the quantity of TNF in the absence of PGE2 is normalized to 100% for each genotype to illustrate differences in the effects of PGE2. Mean absolute or relative quantities of TNF from six independent BMM cultures of each genotype are plotted, ±SEM. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.005; Holm-Sidak method for multiple comparison. (c) As (b), except that IL-6 was measured. ***p < 0.005. (d) As (b), except that the comparison was between Zfp36+/+ and Zfp36aa/aa BMMs, and n = 3. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.005; Holm-Sidak method for multiple comparison. (e) Wild type BMMs were treated with 10 ng/ml LPS in the absence or presence of 1 nM PGE2 and the indicated concentrations of PF04418948 ((a) specific EP2 antagonist) or ONO-SE3-208 (a) specific EP4 antagonist). TNF was measured by ELISA. The graph represents mean TNF concentration ± SEM from three independent BMM cultures. All statistical comparisons are against the third column, in which BMMs received both LPS and PGE2. n.s., not statistically significant; *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.005; ANOVA.

IL-10 is a potent inhibitor of TNF52, and was previously shown to be induced by PGE2 18, 53, 54. We therefore considered whether anti-inflammatory effects of PGE2 could be mediated by increased expression of IL-10. Although PGE2 increased IL-10 levels, in our hands the effect was modest in magnitude, and achieved statistical significance only in Dusp1−/− BMMs (Supplemental Figure 2). Dusp1−/− BMMs strongly over-expressed IL-10, but also over-expressed TNF. They also demonstrated increased IL-10 expression in response to PGE2, but were relatively insensitive to inhibitory effects of PGE2 on TNF release. Therefore, TNF release appears not to be influenced by variations in endogenous IL-10 levels, possibly because of the different kinetics of expression of the two genes. As others have concluded18, 19, IL-10 cannot account for anti-inflammatory actions of PGE2 in this context.

The inhibitory effect of exogenous PGE2 is strongly time-dependent

If LPS-induced secretion of PGE2 exerts negative feedback via EP4 to limit the expression of inflammatory mediators, the inhibition of COX-2 function and endogenous PGE2 synthesis would be expected to increase TNF release. To test this, we first confirmed that LPS-induced release of PGE2 was effectively eliminated by a selective inhibitor of COX-2 enzymatic activity, NS398 (Fig. 6a). The effect of NS398 on LPS-induced release of TNF was then tested in Dusp1−/− and Dusp1+/+ BMMs. Neither genotype of BMM displayed any change of TNF expression in the presence of a concentration of NS398 sufficient to inhibit LPS-induced PGE2 release (Fig. 6b). Differences of timing could explain why the expression of TNF is sensitive to exogenously added but insensitive to endogenously produced PGE2. The accumulation of PGE2 is a gradual process requiring both de novo gene expression and several catalytic steps, such that PGE2 levels in cell culture medium become elevated only after 4 h (Figs 1f and 2d). In contrast the activation of Dusp1 gene expression is rapid and transient, and cooperative regulation by LPS and PGE2 is short-lived (Fig. 4e). Therefore, in cells exposed to synchronous stimulation, most of the important regulatory processes are likely to have occurred before endogenously generated PGE2 levels are high enough to have an impact. To test this concept, BMMs were stimulated for 4 h with LPS, without addition of exogenous PGE2, or with addition 1 h before the LPS stimulus, at the same time as the stimulus, 1 h or 2 h after the stimulus. PGE2 was able to inhibit TNF biosynthesis only if added before or at the same time as the LPS stimulus (Fig. 6c). Although the majority of LPS-induced TNF production occurred after 1 h (Fig. 5a), addition of PGE2 at 1 h or later had no significant inhibitory effect.

Anti-inflammatory effects of PGE2 are strongly time-limited. Dusp1+/+ and Dusp1−/− BMMs were stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS in the presence of the indicated concentrations of NS398. PGE2 (a) and TNF (b) were measured by ELISA. Graphs represent mean ± SEM from three independent BMM cultures of each genotype. (c) Wild type BMMs were stimulated with 10 ng/ml and harvested four hours later for measurement of TNF by ELISA. PGE2 (1 nM) was added at different time points with respect to the addition of LPS at t = 0. The graph shows mean ± SEM from three independent cultures of BMMs. n.s., not statistically significant; ***p < 0.005; ANOVA.

Discussion

At early time points in the response to LPS, expression of the Ptgs2 gene was enhanced by Dusp1 deletion but unaffected by gain of function mutation of Zfp36 (Fig. 3a, 1 hour). This suggests the existence of a mechanism of regulation of Ptgs2 expression by MAPKs, independent of TTP phosphorylation. For example it is possible that enhanced early MAPK p38 activity in Dusp1−/− BMMs contributes to transcriptional activation of the Ptgs2 gene via NF-κB or other transcription factors55. However, it is clear that this mechanism dwindles in importance as the time course progresses and the contribution of the DUSP1-TTP axis dominates the expression of Ptgs2 mRNA both in vitro (Fig. 3a, 4 hour) and in vivo (Fig. 3d), the cumulative expression of COX-2 protein (Fig. 3b) and the production of PGE2 (Fig. 3c). We could find no evidence that the targeted mutation of TTP had any impact on NF-κB activity or transcription of the target genes that we examined43. In contrast both deletion of the Dusp1 gene and targeted mutation of the Zfp36 gene clearly influenced the stability of Ptgs2 mRNA (Figs 1d and 2b), as well as that of other TTP targets37, 43. These findings place the Ptgs2 gene alongside Tnf, Cxcl1, Cxcl2, Ifnb1, Il1b and several others, as targets of the DUSP1-TTP regulatory axis, which tightly couples mRNA stability to the activity of the MAPK p38 signaling pathway30, 34, 35, 37, 43, 56. Increased expression of the Ptgs2 gene may contribute to the innate immune pathology of both Dusp1−/− and Zfp36−/− mice27, 38, whilst decreased expression of Ptgs2 may play a role in the resistance of Zfp36aa/aa to experimental endotoxemia and arthritis43, 44.

The second half of our study focuses on possible consequences of altered PGE2 release by LPS-activated macrophages. Both mouse and human primary macrophages expressed the adenylyl cyclase-coupled PGE2 receptors EP2 and EP4 and displayed cooperative regulation of Dusp1/DUSP1 gene expression by LPS and exogenous PGE2. In wild type murine macrophages, exogenous PGE2 accelerated the decline of MAPK p38 activity and reduced the expression of COX-2 protein. In Dusp1−/− macrophages neither of these effects was seen (Fig. 4). Our findings reveal a negative feedback loop that is illustrated schematically in Fig. 7. PGE2 down-regulates the expression of COX-2 by increasing the expression of DUSP1, decreasing the activity of MAPK p38 and enhancing the function of TTP. This contrasts with the MAPK p38-dependent positive feedback regulation of COX-2 expression by PGE2 that has been described by others45, 57, 58. We found no evidence for activation of MAPK p38 or induction of COX-2 expression by PGE2 in primary murine macrophages. The reason for the discrepancy is not clear.

Schematic representation of the feedback control of macrophages by PGE2, DUSP1 and TTP. Note that the effects of PGE2-mediated feedback are delayed because of the gradual accumulation of PGE2, and therefore operate in a paracrine rather than autocrine fashion. The figure ilustrates possible regulatory connections, and is not intended to capture all the temporal complexities of feedback control.

Exogenous PGE2 strongly inhibited the LPS-induced expression of TNF by primary mouse macrophages (Fig. 5). The PGE2 receptor EP4 contributed to this anti-inflammatory effect, whereas EP1 or EP3 appeared not to be expressed, and we could not find evidence for involvement of EP2. We are currently investigating whether LPS-induced up-regulation of EP4 sensitizes macrophages to anti-inflammatory effects of PGE2. Importantly, Dusp1 gene disruption and targeted mutation of the Zfp36 (TTP) gene had opposite effects on the expression of TNF, increasing or decreasing it, respectively (Fig. 5b and d, left panels). However, both genetic modifications rendered macrophages similarly insensitive to PGE2-mediated suppression of TNF synthesis (Fig. 5b and d, right panels). These results establish a detailed, novel molecular mechanism for anti-inflammatory effects of PGE2.

IL-10 is a potent anti-inflammatory cytokine52, 59. IL-6 is not merely pro-inflammatory, but also has important functions in resolution and tissue remodeling60. Both Il6 and Il10 genes are well-documented TTP targets27, yet they escaped negative regulation by PGE2. In fact, both were up-regulated by PGE2 in macrophages lacking DUSP1 (Figs 5c and 2). Significantly, both genes are positively regulated by cAMP signaling and have been shown to be induced by PGE2 18, 54, 61,62,63,64,65. This may be an adaptation that permits their continued expression under conditions favoring the suppression of TNF. According to this model (illustrated for Il6 in Fig. 7), PGE2 exerts opposing, direct positive and indirect negative effects on gene expression. It positively regulates expression at the transcriptional level via cAMP signaling, and negatively regulates expression post-transcriptionally via induction of DUSP1, inhibition of MAPK p38 and enhancement of TTP function. In wild type macrophages these effects are balanced. In the absence of DUSP1, the negative regulation is lost and the positive regulation unmasked.

Macrophage TNF biosynthesis was inhibited by exogenously added PGE2 but insensitive to endogenously produced PGE2, most likely due to a time delay in LPS-induced PGE2 biosynthesis (Fig. 6). This discrepancy highlights the artificial nature of in vitro experiments, in which relatively pure cell populations are exposed to a synchronous stimulus. In vivo, as cells migrate to a site of infection or tissue damage, they will encounter a milieu that is continually changing as the inflammatory response peaks and resolves. We suggest that the local biosynthesis of PGE2 helps to shape this program by modulating the responses of cells arriving at different stages. A monocyte or macrophage arriving early and encountering LPS in the absence of PGE2 will generate a response very different from that of a late-arriving cell that encounters LPS in the presence of high concentrations of PGE2. In this sense, PGE2 may provide temporal context for responses to pro-inflammatory stimuli, assisting in transitions between initiation and resolution phases. This mode of action of PGE2 may help to explain why cyclooxygenase inhibition sometimes does not have straightforwardly anti-inflammatory consequences, or can even be toxic to resolution11, 12, 66,67,68.

Methods

Animals and experimental procedures

All mice were maintained at the Biomedical Services Unit of the University of Birmingham. Animal care and experimental procedures were performed according to Home Office gidelines under PPL 40/8003, and approved by the University of Birmingham Local Ethical Review Committee.

In vivo LPS challenge was performed by intraperitoneal injection of PBS or 5 mg/kg LPS. After three hours all mice were humanely killed. Spleens were recovered and homogenized in RLT buffer (Qiagen) prior to isolation of RNA as described below.

Reagents

LPS (E. coli EH100) was from Enzo Life Sciences. PGE2, PF04418948 and ONO-AE3-208 were from Cayman Chemical. Antibodies used in western blotting were from Santa Cruz (COX-2, sc-1745; DUSP1, sc-373841), Cell Signaling Technology (phosphorylated MAPK p38, #9211), Sigma Aldrich (tubulin, T9026 and β-actin, A1978). Flow cytometry antibodies against EP2 and EP4 were from Cayman Chemical (16684 and 16625). All other reagents were from Sigma Aldrich. The generation of Dusp1−/−, Zfp36aa/aa and Dusp1−/−: Zfp36aa/aa mouse strains was previously described37. All strains were back-crossed to C57/BL6J for at least ten generations.

Cell culture

Mice between 6 and 12 weeks of age were humanely culled, bone marrow flushed from femurs, and bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs) obtained by culture for 7 days in RPMI1640 containing 10% heat-inactivated FCS and 100 ng/ml M-CSF. Prior to experimentation, macrophage purity was assessed by flow cytometry. Routinely >95% of cells were F4/80+ at the end of the 7 day culture period. BMMs were harvested by scraping, seeded at a density of 106/ml in appropriate culture vessels and rested overnight in the absence of M-CSF before being stimulated. Primary human macrophages were generated from peripheral blood monocytes of healthy donors as previously described52, by culture for 5–7 days in RPMI1640 containing 10% heat-inactivated FCS and 100 ng/ml M-CSF. After this time, cells were harvested by scraping, seeded at a density of 106/ml and rested overnight in the absence of M-CSF before being stimulated.

Measurement of mRNA

RNA was isolated from primary human or mouse macrophages using QIAshredder columns and RNeasy kits (Qiagen). cDNA was generated using iScript cDNA Synthesis kits (Bio-Rad). Gene expression was measured by quantitative PCR with a Roche Light-Cycler 480 Mark II, using custom-designed primers (Eurofins) and SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara). Relative expression was calculated using th ΔΔCt method with B2m or B2M mRNA for normalization.

For microarray analysis of gene expression in primary mouse macrophages, RNA was prepared as above and processed as described37. For microarray analysis of gene expression in human monocyte-derived macrophages, RNA was prepared as above, cleaned and concentrated then applied to Affymetrix HuGene 1.0 ST arrays. Data analysis was essentially as described37, using two-way mixed model ANOVA in Partek Genomics Suite version 6.6. One of the two mouse microarray experiments has been submitted to the Gene Expression Omnibus (GSE68449) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The second mouse BMM microarray and the human monocyte-derived macrophage microarray experiments are more fully described by manuscripts currently in preparation, and the data will be submitted to GEO in full. In the interim, these datasets are available from the author on reasonable request.

RNA Immunoprecipitation

2 × 107 RAW264.7 cells were left untreated or stimulated with 10 ng/ml LPS for 1 h, then harvested by scraping, washed twice with ice-cold PBS and lysed by repeated freeze-thawing in 1 ml of ice cold polysome lysis buffer (100 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES [pH 7.0], 5 mM MGCl2, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM DTT, 100 U/ml RNase inhibitor, protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktails [Roche]). Immunoprecipitations and mRNA measurements were essentially as described43, except that a pre-immune (PI) rabbit serum was used as the immunoprecipitation control, and quantitative PCR was used to derive fold enrichment of various mRNAs in the anti-TTP immunoprecipitates compared with the PI controls (calculated as 2−ΔCt).

Measurement of proteins and PGE2

Intracellular proteins were detected by western blotting using reagents listed above. Secreted IL-6, TNF and PGE2 were detected by sandwich ELISA using commercial kits, according to manufacturers’ instructions. For detection of cell surface EP4, BMMs were fixed and permeabilized using Cytofix/Cytoperm solution according to manufacturer’s instructions (BD Biosciences) and subjected to flow cytometry using an APC-coupled antibody, Cyan flow cytometer (Beckman Coulter) and FloJo software (TreeStar Inc).

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 6.07. Pairwise comparisons were performed using Holm-Sidak’s method, whilst multiple comparisons were performed using Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. The same marks are used throughout; n.s., not significant; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.005.

References

Wallace, J. L. Prostaglandins, NSAIDs, and gastric mucosal protection: why doesn’t the stomach digest itself? Physiol Rev 88, 1547–1565, doi:10.1152/physrev.00004.2008 (2008).

Kawahara, K., Hohjoh, H., Inazumi, T., Tsuchiya, S. & Sugimoto, Y. Prostaglandin E2-induced inflammation: Relevance of prostaglandin E receptors. Biochim Biophys Acta 1851, 414–421, doi:10.1016/j.bbalip.2014.07.008 (2015).

Chan, C. C. & Rodger, I. W. Selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors as potential therapeutic agents for inflammatory diseases. Adv Exp Med Biol 407, 157–161 (1997).

Sanghi, S. et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors: a painful lesson. Cardiovasc Hematol Disord Drug Targets 6, 85–100, doi:10.1189/jlb.1002483 (2006).

Akaogi, J. et al. Prostaglandin E2 receptors EP2 and EP4 are up-regulated in peritoneal macrophages and joints of pristane-treated mice and modulate TNF-alpha and IL-6 production. J Leukoc Biol 76, 227–236, doi:10.1189/jlb.1203627 (2004).

Birrell, M. A. et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of PGE2 in the lung: role of the EP4 receptor subtype. Thorax 70, 740–747, doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2014-206592 (2015).

Luan, B. et al. CREB pathway links PGE2 signaling with macrophage polarization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112, 15642–15647, doi:10.1073/pnas.1519644112 (2015).

Na, Y. R., Jung, D., Yoon, B. R., Lee, W. W. & Seok, S. H. Endogenous prostaglandin E2 potentiates anti-inflammatory phenotype of macrophage through the CREB-C/EBP-beta cascade. Eur J Immunol 45, 2661–2671, doi:10.1002/eji.201545471 (2015).

Harizi, H., Grosset, C. & Gualde, N. Prostaglandin E2 modulates dendritic cell function via EP2 and EP4 receptor subtypes. J Leukoc Biol 73, 756–763 (2003).

Takayama, K. et al. Prostaglandin E2 suppresses chemokine production in human macrophages through the EP4 receptor. J Biol Chem 277, 44147–44154, doi:10.1074/jbc.M204810200 (2002).

Page, T. H. et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs increase TNF production in rheumatoid synovial membrane cultures and whole blood. J Immunol 185, 3694–3701, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1000906 (2010).

Na, Y. R. et al. Consistent inhibition of cyclooxygenase drives macrophages towards the inflammatory phenotype. PLoS One 10, e0118203, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0118203 (2015).

Kalinski, P. Regulation of immune responses by prostaglandin e2. J Immunol 188, 21–28, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1101029 (2012).

Rodriguez, M. et al. Polarization of the innate immune response by prostaglandin E2: a puzzle of receptors and signals. Mol Pharmacol 85, 187–197, doi:10.1124/mol.113.089573 (2014).

Sakamoto, A., Matsumura, J., Mii, S., Gotoh, Y. & Ogawa, R. A prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype EP4 agonist attenuates cardiovascular depression in endotoxin shock by inhibiting inflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide production. Shock 22, 76–81 (2004).

Tang, E. H., Libby, P., Vanhoutte, P. M. & Xu, A. Anti-inflammation therapy by activation of prostaglandin EP4 receptor in cardiovascular and other inflammatory diseases. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 59, 116–123, doi:10.1097/FJC.0b013e3182244a12 (2012).

Jiang, J. & Dingledine, R. Prostaglandin receptor EP2 in the crosshairs of anti-inflammation, anti-cancer, and neuroprotection. Trends Pharmacol Sci 34, 413–423, doi:10.1016/j.tips.2013.05.003 (2013).

van der Pouw Kraan, T. C., Boeije, L. C., Smeenk, R. J., Wijdenes, J. & Aarden, L. A. Prostaglandin-E2 is a potent inhibitor of human interleukin 12 production. J Exp Med 181, 775–779 (1995).

MacKenzie, K. F. et al. MSK1 and MSK2 inhibit lipopolysaccharide-induced prostaglandin production via an interleukin-10 feedback loop. Mol Cell Biol 33, 1456–1467, doi:10.1128/mcb.01690-12 (2013).

Tsatsanis, C., Androulidaki, A., Venihaki, M. & Margioris, A. N. Signalling networks regulating cyclooxygenase-2. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 38, 1654–1661 (2006).

Ridley, S. H. et al. A p38 MAP kinase inhibitor regulates stability of interleukin-1-induced cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA. FEBS Lett 439, 75–80 (1998).

Dean, J. L., Brook, M., Clark, A. R. & Saklatvala, J. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase regulates cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA stability and transcription in lipopolysaccharide-treated human monocytes. J Biol Chem 274, 264–269 (1999).

Dean, J. L., Sarsfield, S. J., Tsounakou, E. & Saklatvala, J. p38 Mitogen-activated protein kinase stabilizes mRNAs that contain cyclooxygenase-2 and tumor necrosis factor AU-rich elements by inhibiting deadenylation. J Biol Chem 278, 39470–39476 (2003).

Lasa, M. et al. Regulation of cyclooxygenase 2 mRNA stability by the mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 signaling cascade. Mol Cell Biol 20, 4265–4274 (2000).

Sully, G. et al. Structural and functional dissection of a conserved destabilizing element of cyclo-oxygenase-2 mRNA: evidence against the involvement of AUF-1 [AU-rich element/poly(U)-binding/degradation factor-1], AUF-2, tristetraprolin, HuR (Hu antigen R) or FBP1 (far-upstream-sequence-element-binding protein 1). Biochem J 377, 629–639 (2004).

Clark, A. R., Dean, J. L. & Saklatvala, J. Post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression by mitogen-activated protein kinase p38. FEBS Lett 546, 37–44 (2003).

Brooks, S. A. & Blackshear, P. J. Tristetraprolin (TTP): Interactions with mRNA and proteins, and current thoughts on mechanisms of action. Biochim Biophys Acta 1829, 666–679, doi:10.1016/j.bbagrm.2013.02.003 (2013).

Wells, M. L., Perera, L. & Blackshear, P. J. An Ancient Family of RNA-Binding Proteins: Still Important! Trends Biochem Sci 42, 285–296, doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2016.12.003 (2017).

Tudor, C. et al. The p38 MAPK pathway inhibits tristetraprolin-directed decay of interleukin-10 and pro-inflammatory mediator mRNAs in murine macrophages. FEBS Lett 583, 1933–1938, doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2009.04.039 (2009).

Clark, A. R. & Dean, J. L. E. The control of inflammation via the phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of tristetraprolin: a tale of two phosphatases. Biochem Soc Trans 44, 1321–1337 (2016).

Fabian, M. R. et al. Structural basis for the recruitment of the human CCR4-NOT deadenylase complex by tristetraprolin. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20, 735–739, doi:10.1038/nsmb.2572 (2013).

Clement, S. L., Scheckel, C., Stoecklin, G. & Lykke-Andersen, J. Phosphorylation of tristetraprolin by MK2 Impairs AU-rich element mRNA decay by preventing deadenylase recruitment. Mol Cell Biol 31, 256–266, doi:10.1128/MCB.00717-10 (2011).

Marchese, F. P. et al. MAPKAP kinase 2 blocks tristetraprolin-directed mRNA decay by inhibiting CAF1 deadenylase recruitment. J Biol Chem 285, 27590–27600, doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.136473 (2010).

Kratochvill, F. et al. Tristetraprolin-driven regulatory circuit controls quality and timing of mRNA decay in inflammation. Mol Syst Biol 7, 560, doi:10.1038/msb.2011.93 (2011).

Sedlyarov, V. et al. Tristetraprolin binding site atlas in the macrophage transcriptome reveals a switch for inflammation resolution. Mol Syst Biol 12, 868 (2016).

Prabhala, P. et al. Temporal regulation of cytokine mRNA expression by tristetraprolin: dynamic control by p38 MAPK and MKP-1. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 308, L973–980, doi:10.1152/ajplung.00219.2014 (2015).

Smallie, T. et al. Dual-Specificity Phosphatase 1 and Tristetraprolin Cooperate To Regulate Macrophage Responses to Lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol 195, 277–288, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1402830 (2015).

Abraham, S. M. & Clark, A. R. Dual-specificity phosphatase 1: a critical regulator of innate immune responses. Biochem Soc Trans 34, 1018–1023 (2006).

Liu, Y., Shepherd, E. G. & Nelin, L. D. MAPK phosphatases–regulating the immune response. Nat Rev Immunol 7, 202–212, doi:10.1038/nri2035 (2007).

Lei, K. et al. Progesterone and the Repression of Myometrial Inflammation: The Roles of MKP-1 and the AP-1 System. Mol Endocrinol 29, 1454–1467, doi:10.1210/me.2015-1122 (2015).

Korhonen, R. et al. Attenuation of the acute inflammatory response by dual specificity phosphatase 1 by inhibition of p38 MAP kinase. Mol Immunol 48, 2059–2068, doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2011.06.439 (2011).

Sawaoka, H., Dixon, D. A., Oates, J. A. & Boutaud, O. Tristetraprolin binds to the 3′-untranslated region of cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA. A polyadenylation variant in a cancer cell line lacks the binding site. J Biol Chem 278, 13928–13935 (2003).

Ross, E. A. et al. Dominant Suppression of Inflammation via Targeted Mutation of the mRNA Destabilizing Protein Tristetraprolin. J Immunol 195, 265–276, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1402826 (2015).

Ross, E. A. et al. Treatment of inflammatory arthritis via targeting of tristetraprolin, a master regulator of pro-inflammatory gene expression. Ann Rheum Dis, 612–619, doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209424 (2017).

Mancini, A. D. & Di Battista, J. A. The cardinal role of the phospholipase A(2)/cyclooxygenase-2/prostaglandin E synthase/prostaglandin E(2) (PCPP) axis in inflammostasis. Inflamm Res 60, 1083–1092, doi:10.1007/s00011-011-0385-7 (2011).

Burgun, C., Esteve, L., Humblot, N., Aunis, D. & Zwiller, J. Cyclic AMP-elevating agents induce the expression of MAP kinase phosphatase-1 in PC12 cells. FEBS Lett 484, 189–193 (2000).

Kaur, M., Chivers, J. E., Giembycz, M. A. & Newton, R. Long-acting beta2-adrenoceptor agonists synergistically enhance glucocorticoid-dependent transcription in human airway epithelial and smooth muscle cells. Mol Pharmacol 73, 203–214, doi:10.1124/mol.107.040121 (2008).

Ryser, S., Massiha, A., Piuz, I. & Schlegel, W. Stimulated initiation of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 (MKP-1) gene transcription involves the synergistic action of multiple cis-acting elements in the proximal promoter. Biochem J 378, 473–484 (2004).

Zhang, J. et al. Cyclic AMP inhibits JNK activation by CREB-mediated induction of c-FLIP(L) and MKP-1, thereby antagonizing UV-induced apoptosis. Cell Death Differ, doi:10.1038/cdd.2008.87 (2008).

Korhonen, R. et al. Attenuation of TNF production and experimentally induced inflammation by PDE4 inhibitor rolipram is mediated by MAPK phosphatase-1. Br J Pharmacol 169, 1525–1536, doi:10.1111/bph.12189 (2013).

Rumzhum, N. N. & Ammit, A. J. Prostaglandin E2 induces expression of MAPK phosphatase 1 (MKP-1) in airway smooth muscle cells. Eur J Pharmacol 782, 1–5, doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.04.041 (2016).

Smallie, T. et al. IL-10 inhibits transcription elongation of the human TNF gene in primary macrophages. J Exp Med 207, 2081–2088, doi:10.1084/jem.20100414 (2010).

Draijer, C. et al. PGE2-treated macrophages inhibit development of allergic lung inflammation in mice. J Leukoc Biol 100, 95–102, doi:10.1189/jlb.3MAB1115-505R (2016).

Williams, J. A., Pontzer, C. H. & Shacter, E. Regulation of macrophage interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-10 expression by prostaglandin E2: the role of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Interferon Cytokine Res 20, 291–298 (2000).

Weber, A., Wasiliew, P. & Kracht, M. Interleukin-1 (IL-1) pathway. Sci Signal 3, cm1, doi:10.1126/scisignal.3105cm1 (2010).

McGuire, V. A. et al. IFNbeta production is regulated by p38 MAPK in macrophages via both MSK1/2 and TTP dependent pathways. Mol Cell Biol, doi:10.1128/mcb.00454-16 (2016).

Faour, W. H. et al. Prostaglandin E(2) regulates the level and stability of cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA through activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in interleukin-1 beta-treated human synovial fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 276, 31720–31731 (2001).

Rosch, S., Ramer, R., Brune, K. & Hinz, B. Prostaglandin E2 induces cyclooxygenase-2 expression in human non-pigmented ciliary epithelial cells through activation of p38 and p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 338, 1171–1178, doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.10.051 (2005).

Williams, L. M., Ricchetti, G., Sarma, U., Smallie, T. & Foxwell, B. M. Interleukin-10 suppression of myeloid cell activation–a continuing puzzle. Immunology 113, 281–292 (2004).

Mauer, J., Denson, J. L. & Bruning, J. C. Versatile functions for IL-6 in metabolism and cancer. Trends Immunol 36, 92–101, doi:10.1016/j.it.2014.12.008 (2015).

Edwards, M. R., Haas, J., Panettieri, R. A. Jr., Johnson, M. & Johnston, S. L. Corticosteroids and beta2 agonists differentially regulate rhinovirus-induced interleukin-6 via distinct Cis-acting elements. J Biol Chem 282, 15366–15375 (2007).

Kaur, M. et al. Effect of {beta}2-adrenoceptor agonists and other cAMP-elevating agents on inflammatory gene expression in human airways smooth muscle cells: A role for protein kinase A. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol, doi:10.1152/ajplung.00046.2008 (2008).

Clark, K. et al. Phosphorylation of CRTC3 by the salt-inducible kinases controls the interconversion of classically activated and regulatory macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109, 16986–16991, doi:10.1073/pnas.1215450109 (2012).

Feng, W. G. et al. cAMP elevators inhibit LPS-induced IL-12 p40 expression by interfering with phosphorylation of p38 MAPK in murine peritoneal macrophages. Cell Res 12, 331–337 (2002).

Jozefowski, S., Bobek, M. & Marcinkiewicz, J. Exogenous but not endogenous prostanoids regulate cytokine secretion from murine bone marrow dendritic cells: EP2, DP, and IP but not EP1, EP3, and FP prostanoid receptors are involved. Int Immunopharmacol 3, 865–878, doi:10.1016/s1567-5769(03)00072-9 (2003).

Bystrom, J. et al. Resolution-phase macrophages possess a unique inflammatory phenotype that is controlled by cAMP. Blood 112, 4117–4127, doi:10.1182/blood-2007-12-129767 (2008).

Gilroy, D. W. et al. Inducible cyclooxygenase may have anti-inflammatory properties. Nature Medicine 5, 698–701 (1999).

Chan, M. M. & Moore, A. R. Resolution of inflammation in murine autoimmune arthritis is disrupted by cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition and restored by prostaglandin E2-mediated lipoxin A4 production. J Immunol 184, 6418–6426, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0903816 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Programme Grant 19614 from Arthritis Research UK. We are grateful to Jason Turner for assistance with flow cytometry experiments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.R.C. devised the study, interpreted experiments and wrote the manuscript. T.T., T.E.S., T.S., H.E.C., E.A.R., D.R.R. and J.D.O’.N. designed, performed and interpreted experiments and contributed to the preparation of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, T., Scambler, T.E., Smallie, T. et al. Macrophage responses to lipopolysaccharide are modulated by a feedback loop involving prostaglandin E2, dual specificity phosphatase 1 and tristetraprolin. Sci Rep 7, 4350 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-04100-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-04100-1

This article is cited by

-

DUSP1/MKP-1 represents another piece in the P2X7R intracellular signaling puzzle in cerebellar cells: our last journey with Mª Teresa along the purinergic pathways of Eden

Purinergic Signalling (2024)

-

Aquaporins (AQPs) as a marker in the physiology of inflammation and its interaction studies with garcinol

Inflammopharmacology (2024)

-

Microbiota promotes recruitment and pro-inflammatory response of caecal macrophages during E. tenella infection

Gut Pathogens (2023)

-

Endotoxin tolerance and low activation of TLR-4/NF-κB axis in monocytes of COVID-19 patients

Journal of Molecular Medicine (2023)

-

Molecular docking prediction and in vitro studies elucidate anti-inflammatory effect of Garcinia extract against inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase-2 targets

Beni-Suef University Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.