Abstract

Zearalenone (ZEA) is one of the main mycotoxins widely spread in contaminated cereal crops, which poses a great threat to food safety as well as human and animal health. Biological control strategies are emerging as important solutions to eliminate mycotoxin contaminations. However, molecular mechanisms underlying ZEA cytotoxic effects are only partly understood. Noncoding RNAs and chromatin accessibilities are important regulators of gene expression and implicate in a variety of biological processes. Here, we established a study model of porcine intestinal epithelial cells upon ZEA exposure and presented a RNA-seq dataset for mRNA, microRNA, and lncRNA profiling in 18 experimental samples. In addition, chromatin accessibilities of four samples were also explored by ATAC-seq. This dataset will shed new light on gene expression profiling and transcriptional regulation of animal cells in the response to ZEA exposure, which further contributes to detecting biomarkers and drug targets for predicting and controlling ZEA contamination.

Measurement(s) | chromatin organization involved in regulation of transcription • mRNA • lnc_RNA • miRNA |

Technology Type(s) | assay for transposase-accessible chromatin using sequencing • RNA sequencing |

Factor Type(s) | zearalenone exposure |

Sample Characteristic - Organism | Sus scrofa |

Sample Characteristic - Environment | cereal grain food product • intestinal epithelium |

Machine-accessible metadata file describing the reported data: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.10272203

Similar content being viewed by others

Background & Summary

Zearalenone (ZEA) is one the main mycotoxins produced by a variety of Fusarium fungal species and widely spread in contaminated cereal crops including maize, wheat, barley and oats1. After ingestion and absorption, ZEA is mainly metabolized by intestinal cells and hepatocytes. Because of the structural similarities of ZEA to endogenous estrogen, ZEA can result in serious endocrine disruption and reproductive disorders in animals2,3. In addition, ZEA was also found to cause toxic effects on liver and kidney functions4,5, and lymphocyte proliferation6. ZEA is chemically stable and cannot be removed by the manufacturing process, which poses great risks to food safety as well as human and animal health. Biological control strategies are emerging as promising solutions to eliminate mycotoxin contaminations. Therefore, it is becoming increasingly important to further understand the molecular mechanisms underlying ZEA toxic effects for developing strategies controlling ZEA contamination. Disruption of gene expression programs is an important event through which mycotoxins exert cytotoxic effects. Recent studies have preliminarily investigated the effects of ZEA exposure on genome wide gene expression in porcine epithelial cells7,8. However, the regulatory networks involved in gene expression alterations in animal cells upon ZEA exposure remain largely unknown.

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and microRNAs (miRNAs) are noncoding RNAs that act as important regulators involved in a variety of physiological, developmental and disease processes at the post-transcriptional level of their target genes9. LncRNAs are a class of transcripts with the length of greater than 200 nucleotides, and miRNAs are transcripts with the length of ~22 nucleotides. LncRNAs and miRNAs can either independently regulate target mRNA expression or functionally interact to control the expression of target mRNAs10. Therefore, identification of expression patterns of lncRNAs and miRNAs can greatly contribute to revealing the molecular events relevant to the phenotypic changes. Chromatin accessibility represents genomic regions binding with regulatory factors responsible for gene transcription, which can be measured by Tn5 transposase-accessible chromatin sequencing (ATAC-seq). Recently, ATAC-seq has become an effective and powerful tool to capture open chromatin to identify the regulatory elements of gene transcription11.

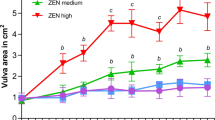

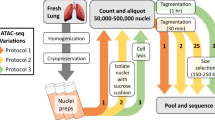

In this study, we performed genome-wide analyses of the expressions of mRNA, miRNA, and lncRNA in porcine intestinal epithelial cells upon ZEA exposure (Fig. 1a). In total, 18 samples were sequenced on the Illumina Hiseq Platform, generating a total of 1,052,122,031 clean reads after quality control (Tables 1, 2). In addition, changes in chromatin accessibilities upon ZEA exposure were also explored by ATAC-seq (Fig. 1a; Table 1), which yielded a total of 230,639,896 clean reads (Table 3). Integrative bioinformatic analysis workflow of RNA-seq and ATAC-seq data is shown in Fig. 1b. These data will provide comprehensive insight into gene expression profiles and transcriptional regulation of animal cells in the response to ZEA exposure, which may aid the detection of biomarkers and drug targets for predicting and controlling ZEA contamination.

Overview of study design and data analysis workflow. (a) Collection and preparation of experimental samples. (b) The data analysis workflow for sequencing data. (c) Effects of ZEA exposure on cell viability of porcine intestinal epithelial cells IPEC-J2. Bars indicate mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). **P < 0.01.

Methods

Sample preparation and collection

Porcine intestinal epithelial cells (IPEC-J2) were inoculated in 6-well plate at a density of 5 × 105 cells/mL and cultured overnight in a CO2 incubator at 37 °C. ZEA was then added to the medium of experimental wells at a final concentration of 10 µg/mL, which can induce cytotoxicity in porcine intestinal epithelial cells as previously reported12,13. An equal volume of phosphate buffer saline was added to the medium of control wells. ZEA-treated and control cells were cultured for 48 h and collected for RNA-seq and ATAC-seq (Table 1). Cell viability was gauged using the Cell Counting Kit-8 following the manufacturer’s protocols (Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan) on the platform of Tecan Infinite 200 microplate reader (Sunrise, Tecan, Switzerland). Significant reduction of cell viability was observed upon ZEA exposure, indicating the toxic effects elicited by ZEA on IPEC-J2 cells (Fig. 1c). Three ZEA-treated and three control samples were collected for mRNA, microRNA, and lncRNA sequencing, respectively (Table 1). In addition, two ZEA-treated and two control samples were collected for ATAC-seq analysis (Table 1).

Library preparation for mRNA sequencing

Total RNA of the experimental samples was extracted using the Trizol method following the manufacturer’s protocols (Tiangen, Beijing, China). A total amount of 3 µg of RNA per sample was used for mRNA sequencing library preparations using NEBNext Ultra RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocols. Index codes were added to attribute sequences to each sample. The library was quantified using the Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA) and diluted into 1 ng/μL, and the library quality was assessed on the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). Clustering of the index-coded samples was conducted on a cBot Cluster Generation System using TruSeq SR Cluster Kit v3-cBot-HS (Illumia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Following cluster generation, the library preparations were then sequenced on the Illumina Hiseq. 2500 platform and 150 bp paired-end reads were yielded.

Library preparation for miRNA sequencing

Total RNA of the experimental samples was extracted using the Trizol method following the manufacturer’s protocols (Tiangen, Beijing, China). A total amount of 3 μg of RNA for each sample was used for sequencing library preparation using the NEBNext Small RNA Library Prep Set for Illumina (NEB, MA, USA) following the vendor’s instructions (Illumina, CA, USA). The library was quantified using the Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA) and diluted into 1 ng/μL, and the library quality was assessed on the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA) using DNA High Sensitivity Chips. Clustering of the index-coded samples was conducted on a cBot Cluster Generation System using TruSeq SR Cluster Kit v3-cBot-HS (Illumina, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. The library preparations were then sequenced on the Illumina Hiseq. 2500 platform and 50 bp single-end reads were produced.

Library preparation for lncRNA sequencing

Total RNA of the experimental samples was extracted using the Trizol method following the manufacturer’s protocols (Tiangen, Beijing, China). A total amount of 3 μg of RNA of each sample was used for library construction, and ribosomal RNA was removed by Epicentre Ribo-zero rRNA Removal Kit (Epicentre, WI, USA). Sequencing libraries were prepared using the rRNA-depleted RNA by NEBNext Ultra Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (NEB, MA, USA) following manufacturer’s recommendations. The library was quantified using the Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA) and diluted into 1 ng/μL, and the library quality was evaluated on the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). Clustering of the index-coded samples was conducted on a cBot Cluster Generation System using TruSeq SR Cluster Kit v3-cBot-HS (Illumia, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s guidelines. The library preparations were then sequenced on the Illumina Hiseq. 2500 platform and 150 bp paired-end reads were produced.

Transcripts expression quantification

Paired-end clean reads of mRNA sequencing (Table 2) were aligned to the Sscrofa11.1 genome assembly (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/?term=pig) using HISAT214. More than 93% of the clean reads of each sample were mapped to the reference genome (Table 2). Read numbers mapped to each gene were counted using featureCounts15. The FPKM (expected number of Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript sequence per Millions base pairs sequenced) value of each gene was determined by the length of the gene and read counts mapped to this gene and used for estimating gene expression levels16. Gene expression data have been uploaded in Figshare17.

For miRNA clean reads, length filter was first processed for all samples (Table 1). The filtered reads were then mapped to the Sscrofa11.1 genome assembly using Bowtie18 without mismatch to analyze their expression and distribution (Table 2). Mapped small RNA tags were utilized to identify known miRNAs using miRDeep219 based on miRBase 22 (http://www.mirbase.org/). Custom scripts were used to quantify the miRNA counts and base bias on the first position of identified miRNA with certain length. For novel miRNA prediction, miREvo20 and miRDeep219 were integrated to predict novel miRNAs by exploring the second structure, Dicer cleavage site, and minimum free energy of the unannotated small RNA tags. miRNA expression levels were normalized as follows: normalized expression = mapped read count × 106/library size21. Target gene prediction of miRNAs was performed using miRanda22. The expression levels of known miRNAs and novel miRNAs, and the predicted target genes are available at Figshare17.

The paired-end clean reads of lncRNA sequencing (Table 2) were aligned to the Sscrofa11.1 genome assembly using HISAT214. The mapped reads of each sample were assembled using StringTie23 via a reference-based method. FPKM of lncRNAs in each sample was then calculated using StringTie23. The assembled transcripts were selected based on following criteria: number of exons ≥2; the length >200 bp nucleotides; non-overlap with the annotated exons in the reference genome. Four programs including Pfam-scan (v1.3)24, CPC2 (v0.1)25, PhyloCSF (v20121028)26, and CNCI (v2)27 with default parameters were used to assess the coding potential of transcripts. Transcripts predicted with coding potential by any of the four tools were removed, and those without coding potential were considered as candidate lncRNAs. Prediction of lncRNA-mRNA co-location networks was conducted with the parameters of upstream and downstream 100 kb of the location of lncRNAs. LncRNA-mRNA co-expression networks were predicted with R function “cor.test”, and mRNAs with absolute value of the correlation coefficient greater than 0.95 were retained. The expression levels of lncRNAs, lncRNA-mRNA co-location networks, and lncRNA-mRNA co-expression networks are available at Figshare17.

Differential expression analysis

Following expression quantification, differential expression analyses of miRNAs, lncRNAs, and mRNAs between ZEA-treated and control groups were performed using DESeq. 228. Benjamini and Hochberg’s method was applied to correct the resulting P-values for controlling false discovery rate. The mRNAs with a corrected P-value < 0.05 and |log2 fold change| ≥ 1 were defined as differentially expressed (Fig. 2a). The miRNAs with |log2 fold change| ≥ 1 and a P-value < 0.05 were defined as differential expression miRNAs (Fig. 2b). The lncRNAs with a corrected P-value < 0.05 were defined as differential expression lncRNAs (Fig. 2c). The differential expression data of miRNA, lncRNAs, and mRNAs are available at Figshare17.

Volcano plot of differential expression profiles between ZEA-treated and control groups. (a) Differential expression of mRNAs. (b) Differential expression of miRNAs. (c) Differential expression of lncRNAs. Green dots represent significant down-expression, and red dots represent significant up-expression.

Library construction for ATAC-seq

ATAC-seq was conducted according to the protocols previously reported29. In brief, the nuclei were extracted and resuspended in the Tn5 transposase reaction mix. The transposition reaction was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Post transposition, the equimolar adapter1 and adapter 2 were added, and then PCR was performed to amplify the library. The library was purified with the AMPure beads and measured with Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer for quality assessment (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA). Clustering of the index-coded samples was performed on a cBot Cluster Generation System using TruSeq SR Cluster Kit v3-cBot-HS (Illumia, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The library preparations were sequenced on the Illumina Hiseq. 2500 platform by Novogene Bioinformatics Institute (Novogene, Beijing, China) and 150 bp paired-end reads were generated.

ATAC-seq data analysis

Paired-end clean reads (Table 3) were aligned to the Sscrofa11.1 genome assembly using BWA30 with default parameters. Read density (Fig. 3a) within 3 kb upstream and 3 kb downstream of the transcription start site was calculated using coumputeMatrix of DeepTools31. Peak calling was then performed using MACS232. All reads were shifted towards the 3′ direction to the length of insert fragments, and the dynamic λ of each 200 bp sliding window was calculated. P values of each window were calculated based on the Poisson distribution and corrected using the false discovery rate method. The regions with a corrected P-value < 0.05 were defined as peaks, and the peaks have been submitted to Figshare17. The Homer software suite33 was utilized to recognize motif sequence in the 250 bp upstream and 250 bp downstream of the peak summits. Motif sequences were matched to the known motifs of transcription factors (Fig. 3b). The distance of peak summits to the nearest transcription start site and corresponding genes were analyzed using the PeakAnalyzer tool34. Differential peaks between ZEA-treated and control groups were identified by calculating the ratio of fold rich between the two groups. Peaks with |log2 fold rich ratio| ≥ 1 were defined as differential peaks. Hierarchical clustering analysis was performed to display the enrichment pattern of peaks in the two groups (Fig. 3c). Differential peaks between the two groups have been submitted to Figshare17.

Reads distribution analysis and peak calling of ATAC-seq data. (a) Read density within 3 kb upstream and 3 kb downstream of the transcription start site. (b) Motif enrichment differences of known transcription factors in ZEA-treated and control samples. (c) Hierarchical clustering of peak enrichment patterns between ZEA-treated and control groups. TSS: transcription start site.

Data Records

Technical Validation

RNA quality control

RNA degradation and contamination was monitored on 1% agarose gels. The concentration and integrity of RNA samples were measured using the Qubit Fluorometer (Thermo Scientific, MA, USA) and Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer platform (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). Samples with rRNA ratio (28S/18S) ≥ 1.9 and RNA integrity number ≥8 were subjected to sequencing library construction.

Quality validation and analyses

We examined the error rate of mRNA (Fig. 4a), miRNA (Fig. 4b), and lncRNA (Fig. 4c) read sequence and found high-quality sequences across all read bases. Raw sequencing data of mRNA, miRNA, and lncRNA (Table 2) were filtered to remove the reads with 5′ adapter contaminants, without 3′ adapter or the insert tag, with the proportion of N base greater than 10%, with poly A/T/G/C, and low quality reads (proportion of the bases with Qphred < = 20 greater than 30% of the total read bases) using FastQC36. All samples produced >97% clean reads after quality control, and >90% of clean reads were mapped to the reference genome (Table 2). In parallel, Q20, Q30, and GC content of the clean data were calculated (Table 2). These analyses indicated the high-quality of library construction and sequencing data of experimental samples. Genomic distribution analysis showed that on average 86.59% of the mapped reads of control samples and 86.98% of the mapped reads of ZEA-treated samples were mapped to exons (Fig. 4d), suggesting the efficient reflection of genome-wide gene expressions. Length distribution analysis of miRNA read sequence showed that most of the reads (88.6%) were in the length of 21~24 nt (Fig. 4e), which was consistent with the biological features of small RNAs. Pearson correlation analysis was performed to further examine the reproducibility of biological replicates in different groups. Correlation coefficients of mRNA sequencing replicates within ZEA-treated and control groups were greater than 0.99 (Fig. 5a). Correlation coefficients of miRNA sequencing replicates within the two groups were greater than 0.98 (Fig. 5b), and those of lncRNA sequencing replicates within the two groups were greater than 0.85 (Fig. 5c).

Quality assessment of mRNA, miRNA, and lncRNA sequencing data. (a) Error rate distribution along mRNA sequencing reads. (b) Error rate distribution along miRNA sequencing reads. (c) Error rate distribution along lncRNA sequencing reads. (d) Read distribution in genomic contexts of exon, intron, and intergenic regions. (e) Length distribution of mapped miRNA sequencing reads.

Pearson correlation analysis of experimental samples within ZEA-treated and control groups. (a) Pearson correlation between samples used for mRNA expression analysis. (b) Pearson correlation between samples used for miRNA expression analysis. (c) Pearson correlation between samples used for lncRNA expression analysis.

For ATAC-seq data, raw reads (Table 3) were first trimmed using Skewer37 to remove the reads with sequencing adaptors, with proportion of N base greater than 10%, low quality reads (proportion of the bases with Qphred < = 20 greater than 30% of the total reads bases), and the reads with the length smaller than 18 nt after trimming. To ensure the reliability of read mapping, reads with mapping quality > 13 and properly paired reads were retained for subsequent analysis. The size distribution of sequenced fragments displayed clear periodicity, and the regions around transcription start sites were enriched for ATAC-seq reads (Fig. 6). The two standard quality metrics demonstrated the ATAC-seq data quality to capture the accessible chromatin regions (Fig. 6). Moreover, the Pearson correlation coefficients are 0.969 of ZEA-treated replicates and 0.964 of control replicates (Fig. 7a), indicating high reproducibility of accessible chromatin regions between replicates within the two groups. We identified peaks by using the MACS2 program32. Peak scores (–log10 (corrected P value)) were calculated and most of the peaks showed a peak score >20 (Fig. 7b), indicating the high reliability of peak calling.

Code availability

HISAT2: http://ccb.jhu.edu/software/hisat2/index.shtml. Version: 2.0.5. Parameters: –rna-strandness RF.

Bowtie: http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml. Version: 0.12.9. Parameters: -v 0 –k 1.

miRDeep2: https://github.com/rajewsky-lab/mirdeep2. Version: 2.0.0.8. Parameters: quantifier.pl -p -m -r -y -g 0 -T 10.

miREvo: http://evolution.sysu.edu.cn/software/mirevo.htm. Version: 1.1. Parameters: -i -r -M -m -k -p 10 -g 50000.

miRanda: http://miranda.org.uk/. Version: 2.042. Parameters: -sc 140 -en -10 –scale 4 -strict -out.

StringTie: http://ccb.jhu.edu/software/stringtie/. Version: 1.3.1. Parameters: default.

BWA: http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/. Version: 0.7.12. Parameters: -T 25 -k 18.

DeepTools Version: 3.0.2. Parameters: –cor Method Pearson.

MACS2: http://liulab.dfci.harvard.edu/MACS/. Version: 2.1.2. Parameters: -q 0.05–call-summits –nomodel –shift -100 –extsize 200 –keep-dup all.

Homer: http://homer.ucsd.edu/homer/. Version: 4.9.1. Parameters: -gc –len 8, 10, 12, 14.

References

Zinedine, A. et al. Review on the toxicity, occurrence, metabolism, detoxification, regulations and intake of zearalenone: An oestrogenic mycotoxin. Food Chem. Toxicol. 45, 1–18 (2007).

Zhao, F. et al. Multigenerational exposure to dietary zearalenone (zea), an estrogenic mycotoxin, affects puberty and reproduction in female mice. Reprod. Toxicol. 47, 81–88 (2014).

Yang, R. et al. Prepubertal exposure to an oestrogenic mycotoxin zearalenone induces central precocious puberty in immature female rats through the mechanism of premature activation of hypothalamic kisspeptin-gpr54 signaling. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 437, 62–74 (2016).

Liang, Z. et al. Individual and combined effects of deoxynivalenol and zearalenone on mouse kidney. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 40, 686–691 (2015).

Al-Seeni, M., El-Sawi, N., Shaker, S. & Al-Amoudi, A. Investigation of the biochemical and histological changes induced by zearalenone mycotoxin on liver in male mice and the protective role of crude venom extracted from jellyfish Cassiopea andromeda. Food Nutr. Sci. 2, 314–322 (2011).

Vlata, Z. et al. A study of zearalenone cytotoxicity on human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Toxicol. Lett. 165, 274–281 (2006).

Taranu, I. et al. Exposure to zearalenone mycotoxin alters in vitro porcine intestinal epithelial cells by differential gene expression. Toxicol. Lett. 232, 310–325 (2015).

Braicu, C. et al. Evaluation of cellular and molecular impact of zearalenone and Escherichia coli co-exposure on IPEC-1 cells using microarray technology. BMC Genomics 17, 576 (2016).

Morris, K. V. & Mattick, J. S. The rise of regulatory RNA. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15, 423–437 (2014).

Thomson, D. W. & Dinger, M. E. Endogenous microrna sponges: evidence and controversy. Nat. Rev. Genet. 17, 272–283 (2016).

Klemm, S. L., Shipony, Z. & Greenleaf, W. J. Chromatin accessibility and the regulatory epigenome. Nat. Rev. Genet. 1 (2019).

Fan, W. et al. Zearalenone induces ROS-mediated mitochondrial damage in porcine IPEC‐J2 cells. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 31, e21944 (2017).

Goossens, J. et al. Porcine intestinal epithelial barrier disruption by the Fusarium mycotoxins deoxynivalenol and T-2 toxin promotes transepithelial passage of doxycycline and paromomycin. BMC Vet. Res. 8, 245 (2012).

Kim, D., Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 12, 357–360 (2015).

Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923–930 (2013).

Trapnell, C. et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat. Biotech. 28, 511–515 (2010).

Wang, H. et al. Transcriptome and chromatin accessibility in porcine intestinal epithelial cells upon Zearalenone exposure. figshare, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.9759710 (2019).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

Friedlander, M. R. et al. miRDeep2 accurately identifies known and hundreds of novel microRNA genes in seven animal clades. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 37–52 (2011).

Wen, M., Shen, Y., Shi, S. & Tang, T. miREvo: An integrative microRNA evolutionary analysis platform for next-generation sequencing experiments. BMC Bioinformatics 13, 140 (2010).

Zhou, L. et al. Integrated profiling of microRNAs and mRNAs: microRNAs located on Xq27.3 associate with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. PLoS One 5, e15224 (2010).

Enright, A. J. et al. MicroRNA targets in Drosophila. Genome Biol. 5, R1 (2003).

Pertea, M. et al. Transcript-level expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with HISAT, StringTie and Ballgown. Nat. Protoc. 11, 1650–1667 (2016).

Punta, M. et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 263–266 (2011).

Kong, L. et al. Assess the protein-coding potential of transcripts using sequence features and support vector machine. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W345–W349 (2007).

Lin, M. F., Jungreis, I. & Kellis, M. Phylocsf: a comparative genomics method to distinguish protein coding and non-coding regions. Bioinformatics 27, i275–i282 (2011).

Sun, L. et al. Utilizing sequence intrinsic composition to classify protein-coding and long non-coding transcripts. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e166 (2013).

Anders, S. & Huber, W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 11, R106 (2010).

Buenrostro, J. D. et al. Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, dna-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat. Methods 10, 1213–1218 (2013).

Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with burrows-wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009).

Ramirez, F. et al. deepTools: a flexible platform for exploring deep-sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, W187–W191 (2014).

Zhang, Y. et al. Model-based Analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 9, R137 (2008).

Heinz, S. et al. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol. Cell 38, 576–589 (2010).

Salmon-Divon, M., Dvinge, H., Tammoja, K. & Bertone, P. PeakAnalyzer: genome-wide annotation of chromatin binding and modification loci. BMC Bioinformatics 11, 415 (2010).

NCBI Sequence Read Archive, https://identifiers.org/insdc.sra:SRP218038 (2019).

Andrews, S. FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data, http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (2014).

Jiang, H. et al. Skewer: a fast and accurate adapter trimmer for next-generation sequencing paired-end reads. BMC Bioinformatics 15, 182 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Funds (Grant No. 31972535, No. 31702082), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2017M621842, 2018T110564), Qingnan Project of Yangzhou University, and the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.B. conceived and supervised the study. H.W., J.W. and H.Q. performed the experiments. H.W., J.J. and S.W. performed data analyses. H.W. and W.B. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ applies to the metadata files associated with this article.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, H., Jin, J., Wu, J. et al. Transcriptome and chromatin accessibility in porcine intestinal epithelial cells upon Zearalenone exposure. Sci Data 6, 298 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-019-0313-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-019-0313-1

This article is cited by

-

Current status on the molecular biology of zearalenone: its biosynthesis and molecular detection of zearalenone producing Fusarium species

European Journal of Plant Pathology (2021)