Abstract

Maintenance of cell volume against osmotic change is crucial for proper cell functions. Leucine-rich repeat-containing 8 proteins are anion-selective channels that extrude anions to decrease the cell volume on cellular swelling. Here, we present the structure of human leucine-rich repeat-containing 8A, determined by single-particle cryo-electron microscopy. The structure shows a hexameric assembly, and the transmembrane region features a topology similar to gap junction channels. The LRR region, with 15 leucine-rich repeats, forms a long, twisted arc. The channel pore is located along the central axis and constricted on the extracellular side, where highly conserved polar and charged residues at the tip of the extracellular helix contribute to permeability to anions and other osmolytes. Two structural populations were identified, corresponding to compact and relaxed conformations. Comparing the two conformations suggests that the LRR region is flexible and mobile, with rigid-body motions, which might be implicated in structural transitions on pore opening.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$189.00 per year

only $15.75 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hoffmann, E. K., Lambert, I. H. & Pedersen, S. F. Physiology of cell volume regulation in vertebrates. Physiol. Rev. 89, 193–277 (2009).

Pedersen, S. F., Kapus, A. & Hoffmann, E. K. Osmosensory mechanisms in cellular and systemic volume regulation. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 22, 1587–1597 (2011).

Hoffmann, E. K. et al. Role of volume-regulated and calcium-activated anion channels in cell volume homeostasis, cancer and drug resistance. Channels 6950, 380–396 (2015).

Okada, Y. et al. Receptor-mediated control of regulatory volume decrease (RVD) and apoptotic volume decrease (AVD). J. Physiol. 532, 3–16 (2001).

Jentsch, T. J. VRACs and other ion channels and transporters in the regulation of cell volume and beyond. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 17, 293–307 (2016).

Stauber, T. The volume-regulated anion channel is formed by LRRC8 heteromers-molecular identification and roles in membrane transport and physiology. Biol. Chem. 396, 975–990 (2015).

Pedersen, S. F., Klausen, T. K. & Nilius, B. The identification of a volume-regulated anion channel: an amazing Odyssey. Acta Physiol. 213, 868–881 (2015).

Sawada, A. et al. A congenital mutation of the novel gene LRRC8 causes agammaglobulinemia in humans. J. Clin. Invest. 112, 1707–1713 (2003).

Qiu, Z. et al. SWELL1, a plasma membrane protein, is an essential component of volume-regulated anion channel. Cell 157, 447–458 (2014).

Voss, F. K. et al. Identification of LRRC8 heteromers as an essential component of the volume-regulated anion channel VRAC. Science 344, 634–638 (2014).

Kubota, K. et al. LRRC8 involved in B cell development belongs to a novel family of leucine-rich repeat proteins. FEBS Lett. 564, 147–152 (2004).

Smits, G. & Kajava, A. V. LRRC8 extracellular domain is composed of 17 leucine-rich repeats. Mol. Immunol. 41, 561–562 (2004).

Abascal, F. & Zardoya, R. LRRC8 proteins share a common ancestor with pannexins, and may form hexameric channels involved in cell-cell communication. BioEssays 34, 551–560 (2012).

Oshima, A., Tani, K. & Fujiyoshi, Y. Atomic structure of the innexin-6 gap junction channel determined by cryo-EM. Nat. Commun. 7, 13681 (2016).

Maeda, S. et al. Structure of the connexin 26 gap junction channel at 3.5 A resolution. Nature 458, 597–602 (2009).

Bennett, B. C. et al. An electrostatic mechanism for Ca2+-mediated regulation of gap junction channels. Nat Commun 7, 8770 (2016).

Syeda, R. et al. LRRC8 proteins form volume-regulated anion channels that sense ionic strength. Cell 164, 499–511 (2016).

Gradogna, A., Gavazzo, P., Boccaccio, A. & Pusch, M. Subunit-dependent oxidative stress sensitivity of LRRC8 volume-regulated anion channels. J. Physiol. 595, 6719–6733 (2017).

Planells-Cases, R. et al. Subunit composition of VRAC channels determines substrate specificity and cellular resistance to Pt-based anti-cancer drugs. EMBO J. 34, 2993–3008 (2015).

Schober, A. L., Wilson, C. S. & Mongin, A. A. Molecular composition and heterogeneity of the LRRC8-containing swelling-activated osmolyte channels in primary rat astrocytes. J. Physiol. 595, 6939–6951 (2017).

Lutter, D., Ullrich, F., Lueck, J. C., Kempa, S. & Jentsch, T. J. Selective transport of neurotransmitters and-modulators by distinct volume-regulated LRRC8 anion channels. J. Cell Sci. 130, 1122–1133 (2017).

Kawate, T. & Gouaux, E. Fluorescence-detection size-exclusion chromatography for precrystallization screening of integral membrane proteins. Structure 14, 673–681 (2006).

Hattori, M., Hibbs, R. E. & Gouaux, E. A fluorescence-detection size-exclusion chromatography-based thermostability assay for membrane protein precrystallization screening. Structure 20, 1293–1299 (2012).

Kelley, L. A., Mezulis, S., Yates, C. M., Wass, M. N. & Sternberg, M. J. E. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 10, 845–858 (2015).

Ullrich, F., Reincke, S. M., Voss, F. K., Stauber, T. & Jentsch, T. J. Inactivation and anion selectivity of volume-regulated anion channels (VRACs) depend on C-terminal residues of the first extracellular loop. J. Biol. Chem. 291, 17040–17048 (2016).

Ashkenazy, H., Erez, E., Martz, E., Pupko, T. & Ben-tal, N. ConSurf 2010: calculating evolutionary conservation in sequence and structure of proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W529–W533 (2010).

Deneka, D., Sawicka, M., Lam, A. K. M., Paulino, C. & Dutzler, R. Structure of a volume-regulated anion channel of the LRRC8 family. Nature 558, 254–259 (2018).

Kefauver, J. M. et al. Structure of the human volume regulated anion channel. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/323584 (2018).

Goehring, A. et al. Screening and large-scale expression of membrane proteins in mammalian cells for structural studies. Nat. Protoc. 9, 2574–2585 (2014).

Kirchhofer, A. et al. Modulation of protein properties in living cells using nanobodies. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 133–138 (2010).

Mastronarde, D. N. Automated electron microscope tomography using robust prediction of specimen movements. J. Struct. Biol. 152, 36–51 (2005).

Zheng, S. Q. et al. MotionCor2: anisotropic correction of beam-induced motion for improved cryo-electron microscopy. Nat. Methods 14, 331–332 (2017).

Rohou, A. & Grigorieff, N. CTFFIND4: fast and accurate defocus estimation from electron micrographs. J. Struct. Biol. 192, 216–221 (2015).

Scheres, S. H. W. Semi-automated selection of cryo-EM particles in RELION-1.3. J. Struct. Biol. 189, 114–122 (2015).

Kimanius, D., Forsberg, B. O., Scheres, S. H. W. & Lindahl, E. Accelerated cryo-EM structure determination with parallelisation using GPUS in RELION-2. Elife 5, 1–21 (2016).

Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 486–501 (2010).

Adams, P. D. et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D 66, 213–21 (2010).

Battle, A. R., Petrov, E., Pal, P. & Martinac, B. Rapid and improved reconstitution of bacterial mechanosensitive ion channel proteins MscS and MscL into liposomes using a modified sucrose method. FEBS Lett. 583, 407–412 (2009).

Smart, O. S., Neduvelil, J. G., Wang, X., Wallace, B. A. & Sansomt, M. S. P. HOLE: a program for the analysis of the pore dimensions of ion channel structural models. J. Mol. Graph. 14, 354–360 (1996).

Jurrus, E. et al. Improvements to the APBS biomolecular solvation software suite. Protein Sci. 27, 112–128 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the Nureki laboratory, the Kikkawa laboratory, and the RIKEN Center for Biosystems Dynamics Research, especially M. Takemoto and R. Taniguchi (Nureki laboratory) for assistance with the manuscript preparation and H. Shigematsu (RIKEN) for microscope maintenance. We also thank Y. Araiso (Kyoto Sangyo University) for instructions regarding the digitonin preparation; K. Touhara (The Rockefeller University) for advice about the anti-GFP nanobody preparation; and K. Iwasaki, N. Miyazaki, and A. Kawamoto (Osaka University) for optimization of the cryo-EM experiment. This work was supported by a grant from the National Key R&D Program of China (2016YFA0502800); by the RIKEN Pioneering Project ‘Dynamic Structural Biology’; by the Platform for Drug Discovery, Informatics and Structural Life Science from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) to O.N.; by AMED (grant no. JP17gm5010001) to H.I.; by a MEXT Grant-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research (grant no. 16H06294) to O.N.; by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31571083) to Z.Y.; by the Program for Professor of Special Appointment (Eastern Scholar of Shanghai, TP2014008) to Z.Y.; by the Shanghai Rising-Star Program (4QA1400800) to Z.Y.; by the Young 1000 Talent Program of China to Z.Y.; and by JSPS KAKENHI (grant nos. 17J06101 to G.K.; 17K15086 to K.W.; 25221302 to H.I.; 17H03640 to R.I.; 24227004 to O.N.). This research was also supported by the Platform Project for Supporting Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (Basis for Supporting Innovative Drug Discovery and Life Science Research (BINDS)) from AMED (grant nos. JP18am0101072, JP18am0101082 and JP18am0101115).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.K. and O.N. conceived and designed the project. G.K. screened and purified the protein and prepared cryo-EM samples. R.N. assisted with the preparation of cryo-EM samples. M.I., K.W., and H.I. assisted with the functional characterization of samples. N.D. performed the mass spectrometry analyses. G.K., T. Nakane, T.Y., and M.S. performed cryo-EM data collection and processing. T. Nishizawa, T.K., A.T., H.Y., and M.K. assisted with the optimization of the cryo-EM data collection. G.K. and R.I. performed the model building, with assistance from T. Nishizawa. Y.J., M.H., and Z.Y. performed the patch clamping recordings. G.K., R.I., and O.N. wrote the manuscript. O.N. supervised all of the research.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Integrated supplementary information

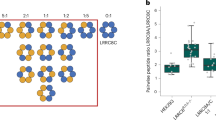

Supplementary Figure 1 Functional properties of the HsLRRC8A protein.

a, FSEC profile on a Superose 6 Increase 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) for the EGFP-fused HsLRRC8A expressed in HEK293S GnTI– cells. The arrows indicate the estimated elution positions of the void volume, EGFP-fused HsLRRC8A, and free EGFP. b, Abundance of each LRRC8 protein normalized to the LRRC8A isoform, as estimated by mass spectrometry. c, List of proteins detected by mass spectrometry from the purified HsLRRC8A protein samples. According to the emPAI (The Exponentially Modified Protein Abundance Index) score, which correlates to the amount of each protein contained in the tested sample, the LRRC8 isoforms (highlighted in yellow) and other detected proteins are listed in descending order of their amounts. d, Single-channel current recordings of the HsLRRC8A protein after reconstitution in liposomes under asymmetric salt conditions (500 mM KCl in bath, 70 mM KCl in pipette) and normalized all-points amplitude histogram analysis of HsLRRC8A in the open and closed states at 100 mV. The gray dashed lines indicate the closed (C) and open (O) states. For the plot, the bin width is set at 0.1 pA/bin and the total count of events is normalized to 1.0. The distribution data were fit by the sum of two Gaussians, and the peaks correspond to the closed (C) and open (O) states. e, Single-channel current recordings of HsLRRC8A after reconstitution in liposomes under symmetric salt conditions (70 mM KCl in bath, 70 mM KCl in pipette) and normalized all-point amplitude histogram analysis of HsLRRC8A at 100 mV. f, HsLRRC8A-induced currents were blocked by 40 μM DCPIB.

Supplementary Figure 2 Cryo-EM analysis of HsLRRC8A.

a, A representative cryo-EM micrograph of HsLRRC8A. Red circles indicate individual particles. The white scale bar represents 50 nm. b, Flowchart of cryo-EM data processing of the HsLRRC8A structure, including particle picking, classification, and 3D refinement. c, Angular distribution plot of particles included in the final 3D reconstruction of HsLRRC8A, with C3 symmetry imposed. d, Fourier shell correlation (FSC) curve of the final 3D reconstruction model calculated using relion_postprocess with masked resolution of 4.25 Å, corresponding to the gold-standard cutoff criterion of FSC = 0.143. e, Cross-validation FSC curves for the refined model versus half maps (Half maps 1 and 2) and versus the summed map.

Supplementary Figure 3 Structural comparison of two adjacent subunits.

a, Two adjacent subunits (α and β subunits) of HsLRRC8A are superimposed on each other. The RMSD value for the 553 Cα atoms from the subunits is 3.79 Å. For clarity, the overall subunits superimposed using only the TM region are presented. b, The extracellular regions from two adjacent subunits are superimposed on each other. The RMSD value for the 68 Cα atoms from the two extracellular regions is 0.39 Å. c, The transmembrane regions from two adjacent subunits are superimposed on each other. The RMSD value for the 110 Cα atoms from the two extracellular regions is 0.40 Å. d, The intracellular regions from two adjacent subunits are superimposed on each other. The RMSD value for the 119 Cα atoms from the two extracellular regions is 0.98 Å. e, The LRR regions from two adjacent subunits are superimposed on each other. The RMSD value for the 395 Cα atoms from the two extracellular regions is 0.47 Å.

Supplementary Figure 4 Subunit interfaces between two adjacent subunits.

a,b, Close-up views between two adjacent subunits at the transmembrane region, showing the tight (a) and loose (b) interactions. c,d, Close-up views between two adjacent subunits at the intracellular region, showing the tight (c) and loose (d) interactions. e,f, Close-up views between two adjacent subunits at the LRR region, showing the tight (e) and loose (f) interactions. g,h, Close-up views between two adjacent subunits at the extracellular region, showing the tight (g) and loose (h) interactions. A surface model with the side chains of the residues lining the subunit interfaces depicted by stick models is presented for each panel. Three adjacent subunits (α, β, and ζ subunits) of HsLRRC8A are colored according to Fig. 1d.

Supplementary Figure 5 Structural similarity between HsLRRC8A, innexin, and connexin.

a–c, The N-terminal halves of the HsLRRC8A subunit (a), the CeInnexin-6 (PDB 5H1Q) subunit (b), and the HsConnexin-26 (PDB 2ZW3) subunit (c) are presented. The subunits of CeInnexin-6 and HsConnexin-26 are colored according to HsLRRC8A coloring. The N and C termini are indicated by “N” and “C”, respectively. In each structure, the cysteine residues forming disulfide bonds at the extracellular region are depicted by stick models. In each panel, a close-up view of the disulfide bonds is shown in the inset. d–f, Solvent-excluded molecular surfaces of HsLRRC8A (d), CeInnexin-6 (e), and HsConnexin-26 (f). The surfaces are colored according to subunit. For HsLRRC8A, the extracellular, TM, and intracellular regions are shown. g–i, Channel pore and N-terminal region of HsLRRC8A (d), CeInnexin-6 (e), and HsConnexin-26 (f). The protein main chains are shown as cylinder models. j, Secondary structure prediction of the N-terminal regions of HsLRRC8A, CeInnexin-6, and HsConnexin-26. Prediction was performed by the program PSIPRED (Buchan, D. W. A. et al. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W563–W568, 2010). The actual locations of the corresponding helices are indicated by the red and pink boxes for NTH and TM1, respectively.

Supplementary Figure 6 Model of the heteromeric LRRC8 protein.

a, Conservation score mapped on the molecular surface of HsLRRC8A. The score was calculated by the program CONSURF26, based on the multiple-sequence alignment of the A–E isoforms shown in the Supplementary Note. The molecular surface is colored according to normalized conservation score, from 0.752 (pink) to –0.983 (purple). b, The model structure of the (LRRC8A)5·LRRC8D heterohexamer, viewed parallel to the membrane (left) and from the extracellular side (right). The homology model of human LRRC8D was generated by the program MODELLER (Fiser, A. & Sali, A. Methods Enzymol. 374, 461–491, 2003), using the alignment in the Supplementary Note, and then the α subunit of the present structure was replaced by this model. In the inset, a close-up view of the channel-pore-forming regions from the extracellular side is shown, and the amino-acid side chains of the constriction site are depicted in stick representations. The five LRRC8A subunits are colored light blue, while the LRRC8D isoform is colored light brown.

Supplementary Figure 7 Structural comparison with MmLRRC8A.

a,b, Subunit interfaces between the α and β subunits (a) and between the β and γ subunits(b). The cylinder models of MmLRRC8A (semitransparent gray) and HsLRRC8A (color-coded as in Fig. 1c) are shown. The extracellular and TM regions of the β subunits of MmLRRC8A (PDB 6G9O) and HsLRRC8A are superimposed on each other. The RMSD value for the 187 Cα atoms from the subunits is 0.99 Å. c, Cross-sections of the TM regions of HsLRRC8A (left) and MmLRRC8A (right), viewed from the extracellular side. d, Schematic drawing depicting the working model for the structural transition of LRRC8, based on the currently available LRRC8A structures.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Text and Figures

Supplementary Figures 1–7, Supplementary Note

Supplementary Video 1

Density map of the HsLRRC8A hexamer. The density map surface is colored according to the local resolution of the map, from 3.8 Å (blue) to 5.7 Å (red)

Supplementary Video 2

Overall structure of the HsLRRC8A hexamer. The ribbon model of the HsLRRC8A hexamer is shown, with the subunits colored red, orange, yellow, green, cyan, and blue

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kasuya, G., Nakane, T., Yokoyama, T. et al. Cryo-EM structures of the human volume-regulated anion channel LRRC8. Nat Struct Mol Biol 25, 797–804 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-018-0109-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-018-0109-6

This article is cited by

-

Physiology of the volume-sensitive/regulatory anion channel VSOR/VRAC. Part 1: from its discovery and phenotype characterization to the molecular entity identification

The Journal of Physiological Sciences (2024)

-

Structural basis for assembly and lipid-mediated gating of LRRC8A:C volume-regulated anion channels

Nature Structural & Molecular Biology (2023)

-

Structure of a volume-regulated heteromeric LRRC8A/C channel

Nature Structural & Molecular Biology (2023)

-

Cryo-EM structure of human heptameric pannexin 2 channel

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Insights into stoichiometry and gating of heteromeric LRRC8A–LRRC8C volume-regulated anion channels

Nature Structural & Molecular Biology (2023)