Abstract

We report the first annotated chromosome-level reference genome assembly for pea, Gregor Mendel’s original genetic model. Phylogenetics and paleogenomics show genomic rearrangements across legumes and suggest a major role for repetitive elements in pea genome evolution. Compared to other sequenced Leguminosae genomes, the pea genome shows intense gene dynamics, most likely associated with genome size expansion when the Fabeae diverged from its sister tribes. During Pisum evolution, translocation and transposition differentially occurred across lineages. This reference sequence will accelerate our understanding of the molecular basis of agronomically important traits and support crop improvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Pea (Pisum sativum L., 2n = 14) is the second most important grain legume in the world after common bean and is an important green vegetable with 14.3 t of dry pea and 19.9 t of green pea produced in 2016 (http://www.fao.org/faostat/). Pea belongs to the Leguminosae (or Fabaceae), which includes cool season grain legumes from the Galegoid clade, such as pea, lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.), chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.), faba bean (Vicia faba L.) and tropical grain legumes from the Milletoid clade, such as common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), cowpea (Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp.) and mungbean (Vigna radiata (L.) R. Wilczek). It provides significant ecosystem services: it is a valuable source of dietary proteins, mineral nutrients, complex starch and fibers with demonstrated health benefits1,2,3,4 and its symbiosis with N-fixing soil bacteria reduces the need for applied N fertilizers so mitigating greenhouse gas emissions5,6,7. Pea was domesticated ~10,000 years ago by Neolithic farmers of the Fertile Crescent, along with cereals and other grain legumes8. The large reservoir of genetic diversity in Pisum has facilitated its spread throughout Asia, Europe, Africa, the Americas and Oceania where it has adapted to diverse environments and culinary practices (https://iyp2016.org/). Due to its large genome size (1 C ~ 4.45 gigabases, Gb9), pea genomics has lagged behind that of legumes with smaller genomes, such as Medicago truncatula Gaertn.10, Lotus japonicus L.11 or soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr)12. Yet, pea has been studied as a genetic model since the eighteenth century; the analysis of the inheritance of different pea morphotypes led Gregor Mendel to uncover the laws of genetics13. Several pea developmental mutations have since been characterized14 and chromosomal regions controlling agronomic traits identified15, but tools exploiting pea diversity for plant breeding, identifying favorable alleles underlying phenotypic variations and accelerating trait improvement by marker-assisted selection have been limited. The pea genome is large, probably resulting from a recent expansion and diversification of retrotransposons16. Early reassociation kinetic studies of the pea genome indicated that 75–97% is made up of a heterogeneous population of repetitive sequences17,18. More recent investigations confirmed the occurrence of highly diverse families of high to moderately repeated sequences comprising about 76% of pea nuclear DNA19. When the repetitive DNA sequences of pea, soybean and M. truncatula are compared, little sequence similarity is found between pea and soybean19. Repetitive sequences between pea and M. truncatula were more similar but differed in abundance. The pea karyotype includes two sub-metacentric (1 and 2) and five acrocentric (3, 4, 5, 6 and 7) chromosomes16. Several major rearrangements, including translocations between nonhomologous chromosomes, have been reported20,21,22.

Technological innovation now enables the sequencing and assembly of large genomes, bridging the gap between models and crops for quantitative trait analysis and genome-wide breeding approaches. Accordingly, an international consortium was formed to produce a reference genome sequence for pea. Here we report the draft assembly of the seven chromosomes of the inbred pea cultivar ‘Caméor’, released by the French breeding company Seminor in 1973 and characterized by its protein-rich seeds. This fully annotated assembly builds on genomic resources developed for Caméor over the last decade (Supplementary Fig. 1) and will enable genomic-assisted crop improvement. It provides insights into legume genome evolution, with resequencing data for 42 wild, landrace and cultivar Pisum genotypes, revealing genomic events that have shaped the evolution of this large and diverse genus.

Results

Genome sequencing and assembly

Complementary approaches were combined to obtain the pea reference genome assembly (Supplementary Fig. 2). Whole-genome Illumina short-read sequences (281× genome coverage; Supplementary Table 1) were assembled into contigs using SoapdeNovo2, then combined into scaffolds using long-range PacBio RSII sequences (13× genome coverage; Supplementary Table 1) and whole-genome profiling of a bacterial articial chromosome (BAC) library23. Scaffolds were manually curated for inter and intrachromosomal chimeras using (1) sequences obtained from single chromosomes isolated by flow-cytometry24 (Supplementary Fig. 3) and (2) an ultra-high-density skim genotyping-by-sequencing genetic map (Supplementary Dataset 1). Curated scaffolds were then integrated into 24,623 super-scaffolds (L50 of 415 kilobases (kb), Supplementary Table 2) using BioNano maps (Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Table 4). The seven pseudomolecules representing the pea chromosomes were obtained by anchoring super-scaffolds onto high-density genetic maps (Supplementary Dataset 2). Pseudomolecules were named according to the reference pea genetic map25 and chromosome numbering24 (Supplementary Table 5).

The pea genome v.1a assembly spans 3.92 Gb (Table 1) representing ~88% of the estimated pea genome size (~4.45 Gb), with 82.5% (3.23 Gb) of sequences assigned to the seven pseudomolecules and 14,266 unassigned scaffolds representing 685 Mb. The estimated size gap between the genome and assembly was mostly due to highly repeated sequences collapsed in the assembly, reflected by repeat proportions in unassembled reads compared to the assembly (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 6). The most under-represented repeats were tandemly arranged satellite repeats and ribosomal RNA genes whose arrays were highly reduced or absent from the assembly, accounting for about 15% of the missing sequence and probably more at the centromeres and telomeres. No group of dispersed repeats was missing from the assembly, but under-representation of high copy number mobile elements accounted for most (~75%) of the difference between assembly length and estimated genome size. Recent long read sequencing technologies should in the future allow access to collapsed repeats and missing sequences.

Centromere positions were indicated by regions of suppressed meiotic recombination revealed by comparing marker positions in the skim-GBS genetic map with the pseudomolecules (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 5). These were confirmed using selected sequences for FISH (Fig. 1b–f). Pea chromosomes are metapolycentric, characterized by extended primary constrictions containing multiple domains of centromeric histone cenH326. The coordinates of nonrecombining regions of the pseudomolecules agreed well with centromere positions obtained from cytogenetic measurements of the pea karyotype (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Notes). Outside centromeres, recombination rate appeared constant along chromosomes and marker order on pseudomolecules was highly (Spearman r > 0.95) collinear with high-density linkage maps of five recombinant inbred line (RIL) populations from intra-specific crosses25 (Supplementary Dataset 2).

a, Circos view of the pea genome. Pseudomolecule color-code is shaded at estimated centromere positions. Lanes depict circular representation of pseudomolecules (a) and the density of retrotransposons, transposons, genes, ncRNA, tRNA and miRNA coding sequences (b–g). Lines in the inner circle represent links between synteny-selected paralogs. b, Estimated positions of centromeres in the assembly and their comparison to pea cytogenetic map is schematically represented, with pseudomolecules as white bars and cytogenetic maps of pea chromosomes as gray bars. Non-recombining regions representing the centromeres are marked in green. Positions of centromeric single-copy FISH markers are indicated above the pseudomolecules in black and positions of arrays of centromeric satellites present in the assembly are shown below them in blue. Positions of primary constrictions on the cytogenetic maps are labeled in red. PisTR-B satellite loci used to discriminate individual chromosomes are shown in purple boxes on the gray bars. c, FISH localization of the satellite repeats TR11/19 (red) and TR10 (green) on metaphase chromosomes (gray). d, Discrimination of chromosomes within the pea karyotype using FISH with PisTR-B probe (purple). e, Example of FISH detection of the single-copy marker (1722, green) in the centromere of chromosome 6. f, Chromosome 6 with labeled centromeric repeat TR11/19. g, The density of different TE lineages inferred from the detection of their protein-coding domains along pseudomolecules.

Repeat annotation and gene prediction

Annotation (Supplementary Fig. 6) identified 2,225,175 repetitive elements clustered into 2,940 consensus sequences representing ~83% of the genome (Table 1 and Fig. 1a). Most of these corresponded to transposable elements (TE) that were further sub-classified (Supplementary Table 7). Retrotransposons (Class I), with 1,945,520 copies, were the most abundant. Long-terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons (1,707,747 copies) represented 72.7% of the genome, with Ty3-gypsy Ogre elements being their major lineage (Supplementary Table 7). The 246,432 transposons (Class II) represented 5.4% of the genome, 84% of which were terminal-inverted repeat (TIR) transposons (Supplementary Table 7). TE family distribution varied across the genome (Fig. 1g). For example, the abundant Ogre family was distributed throughout all chromosomes with a lower density near telomeres. In contrast, Ty1-copia Ivana and Ty3-gypsy TatV were preferentially found near telomeres and Ty3-gypsy chromovirus CRM were mainly located around centromeres.

Ab initio and homology-based methods were combined to annotate protein-coding sequences (Supplementary Notes). In total, 44,756 complete and 29 truncated genes were predicted (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 8), with an average gene length, coding sequence length and exon number of 2,784 base pairs (bp), 1,016 bp and 6.33 exons, respectively. The vast majority of gene models were supported by complementary DNA/expressed sequence tag evidence. The completeness of the gene repertoire was assessed using BUSCO v.3.0.2 (see methods). From a core set of 1,440 single-copy ortholog genes from the Embryophyta lineage, 92.3% were complete in the assembly (67.4% as single-copy, 24.9% as duplicates), 2.7% were fragmented and 5.0% were not found, suggesting that the assembly includes most of the pea gene space. We identified 7,191 long non-coding RNAs, 824 transfer RNAs (tRNAs) and 71 microRNAs (miRNAs) expressed in developing seeds (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Notes). Fourteen of these miRNA and their 67 putative targets were identified for the first time (Supplementary Dataset 3).

Legume genome size evolution

Genome size varies significantly among land plants27. The pea genome (~4.45 Gb (ref. 9)) is within the upper range for the superrosid eudicots27. Among 695 Leguminosae species, only 104 have a larger genome size than P. sativum28. All but three of these belong to the Fabeae tribe, which includes the genera Lathyrus, Vicia, Pisum and Lens. The Fabeae thus display distinctively large genomes compared to the closely related Trifolieae (genome size ~1.05 Gb) and Cicereae (genome size ~1.27 Gb (ref. 28)). The pea genome assembly was thus a good opportunity to study the drivers of genome expansion in the Fabeae.

Genome expansion in plants is primarily driven by polyploidization (whole-genome duplication events) and the proliferation of TEs. A comparison with 21 eudicot species, especially Leguminosae (Supplementary Dataset 4 and Fig. 2a,b), showed that pea has an intermediate number of gene-coding sequences (44,791; Supplementary Dataset 4), ranking fifth after Cajanus cajan (L.) Millsp., M. truncatula, Lupinus angustifolius L. and G. max (Fig. 2a), the latter two exhibiting recent paleo-polyplodization12,29 (Fig. 2b). Notably, the pea genome contains the largest percentage of singletons (54%) as compared to other legumes (Supplementary Dataset 5), which could explain why pea was such a successful plant model in early genetics when large collections of mutants were described for contrasting phenotypes30. Paralogs and orthologs were identified using Orthofinder (Supplementary Notes). The distribution of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (Ks) for pea paralog pairs shows no evidence of a recent whole-genome duplication but reflects the ancestral Papilionoideae whole-genome duplication event (PWGD), estimated to have occurred ~55 million years ago (Ma)10,31 and the whole-genome triplication event common to the core eudicots32. The pea genome shows the highest whole-genome mutation rate among the Leguminosae, as demonstrated by a shift in the pea PWGD-peak (mode at Ks = 1) compared to other species (for example, M. truncatula at Ks = 0.83 and G. max at Ks = 0.61; Supplementary Fig. 7 and Supplementary Table 9), consistent with pea having the highest percentage of genus specific genes (33%; Supplementary Dataset 5). We classified paralog pairs according to their presence or absence among taxonomic lineages (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Dataset 5 and Supplementary Fig. 8). About 75% of pea paralogs, specific to Pisum or to the Trifolieae/Fabae clade, show Ks < 0.4, while most specific to inverted-repeat-lacking clade (IRLC) have Ks just below ~0.4 and for the Leguminosae lineages Ks > 0.4 (Supplementary Fig. 8). In sharp contrast, for M. truncatula paralogs, the Ks distribution is higher than in pea, except for those specific to the Leguminosae lineage where Ks is close to the PWGD-peak (Supplementary Fig. 8). We used synteny as an additional criterion to select a subset of paralog pairs in pea and M. truncatula (Fig. 2d). Many of these pea paralogs appeared to be in tandem and have lower Ks (~0.2) than in M. truncatula (Ks ~ 0.5). Gene number, high whole-genome mutation rate, high proportions of recent paralogs and Pisum-specific genes are all indicative of more frequent gene gain or loss in pea, most likely associated with genome size expansion about 24.7 and 17.5 Ma, coincident with the divergence of the Fabeae from its sister tribes33. The appearance of these paralogs at that time is intriguing and could be related to genome reorganization associated with TE expansion and/or removal34.

a, Number of gene-coding sequences (CDS) against genome size (Mb) for selected Eudicot sequenced genomes (Supplementary Dataset 4). Data points are represented by centered labeled boxes; overlapping points are indicated. b, Maximum likelihood tree calculated using 28 orthologous sequences common to the eudicot species depicted. All clades have 100% support (1,000 bootstrap runs); support is noted otherwise. Branch length represents estimated nucleotide substitutions per site (bar = 0.2 substitutions per site). Whole-genome paleo-polyploidy events are labeled: γ common to all core eudicots, PWGD common to all Papilionoideae within the Leguminosae family; others are lineage-specific (LS): N-LS, S-LS, β and α, SWGD, L-LS, G-LS (Supplementary Notes). c, Ks distribution of paralog pairs classified by their lineage specificity: genus specific (white box plots), specific to genera in the Trifolieae-Fabeae clade (blue; paralog pairs common to Psat, Mt, Tpra and Tsub and absent from all other eudicots in the set), the IRLC (green) or the Papilionoideae (orange) clades. Density is denoted both by violin and quartile box-and-whisker plots. Data points are represented by gray jittered circles. Note x axis is presented on a log scale. d, Distribution of pairwise Ks for intra and interchromosomal synteny-selected paralog pairs within the pea and M. truncatula genome.

The massive increase of Ty3-gypsy, and to a lesser extent Ty1-copia, LTR-retrotransposons accounts for most of the genome size differences between pea and M. truncatula, Trifolium pratense L., L. japonicus, P. vulgaris or G. max10,11,35 (Supplementary Table 10). Investigation of TE representation in Pisum species and subspecies confirmed that TE dynamics has shaped Pisum diversity through successive expansions and deletions (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Dataset 6). P. fulvum has fewer of several retroelements compared to cultivated pea and an increased content of Ogre retroelements. Wild P. s. elatius TE representation is intermediate between P. fulvum and cultivated pea. To determine the historical dynamics of the different Ty3-gypsy and Ty1-copia retroelements in the pea genome, we analyzed the divergence of the reverse transcriptase (RT) and integrase (INT) sequences of different TE lineages, revealing different evolutionary patterns among lineages (Fig. 3b,c). For example, Angela elements are all relatively young, consistent with either an intense and recent burst of insertion or a strong selection against Angela elements. This is in marked contrast to TatV elements, which are the most ancient (Fig. 3b). Interestingly, all TE lineages that showed significant representational differences among Pisum species and subspecies were, on average, older or of the same age as Ogre elements (Fig. 3c).

a, TE representation in P. fulvum, P. s. elatius, P. s. sativum landraces and P. s. sativum cultivars (x axis). The y axis of the plot represents the abundance of selected retrotransposon families as measured by the number of reads mapping to a lineage-specific RT domain divided by the total number of reads that map to all RT domains and by the number of RT domains in the assembly, per million. Letters on each quartile box-and-whisker plot represent statistically different classes among the different groups of accessions (n = 3 P. fulvum, n = 7 P. elatius, n = 10 P. s. sativum landraces and n = 5 P. s. sativum cultivars, Supplementary Dataset 6). b, Neighbor-joining (NJ) trees were built from RT domain sequence similarities among different lineage-specific copies identified in the pea genome v.1a assembly. Deep branching revealed ancient expansion while flat branching is consistent with a recent burst of insertion activity. Red branches correspond to outgroup sequences c, The average age of TEs was revealed for the different lineages by the branching distribution in the NJ trees built from RT (light blue) and INT (yellow) protein domains. The vertical bar ca. branching time 0.10 indicates the peak of Ogre retroelement age distribution. Stars indicate families for which TE representation significantly varied among Pisum taxa (Supplementary Dataset 5). The RT and INT columns give the number of RT and INT domains present in the pea genome.

Paleohistory of modern legume genomes

To assess the paleohistory of modern legume genomes36, we performed homology and synteny analyses (Supplementary Notes) with representatives of the Galegoid (P. sativum, L. japonicus, M. truncatula and C. arietinum) and Millettoid (C. cajan, G. max, P. vulgaris, V. radiata and Vigna angularis (Willid.) Ohwi & H. Ohashi) clades, together with one diploid peanut relative (Arachis duranensis Krapov. & W.C. Greg). Within the Galegoid subfamily, we identified 12,025 ancestral genes (that is, conserved between the four investigated species) defining an ancestral Galegoid karyotype (AGK) of eight conserved ancestral regions (CARs). The pea genome differentiated from this AGK through at least three chromosomal fissions, four fusions and a translocation between chromosomes Ps1 and Ps5. The genome of the closely related M. truncatula evolved through two fissions, two fusions and one translocation (between Mt4-Mt8 (ref. 37), Supplementary Fig. 9). The five Millettoid genomes had 12,387 ancestral genes, defining an ancestral Millettoid karyotype (AMK) of 16 CARs. We then compared AGK, AMK and A. duranensis, an outgroup of the Galegoid and Millettoid subfamilies and identified 25 CARs with 13,181 protogenes. Merging CARs sharing partial synteny between a subset of these extant Millettoid and Galegoid genomes elucidated the ancestral legume karyotype (ALK), consisting of a minimum of 19 proto-chromosomes. We propose a legume evolutionary scenario from the reconstructed ancestral karyotypes showing that the legume genomes have been massively rearranged during their evolution (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 11). This approach delivered the first reconstruction of the Legume (ALK) as well as Galegoid (AGK) and Millettoid (AMK) subfamily ancestors and updated the publicly available catalog of paralogous and orthologous gene relationships between extant legume genomes (https://urgi.versailles.inra.fr/synteny/legumes) for translational research on conserved agronomical traits.

Evolutionary scenario of modern legumes (pea, diploid peanut, lotus, barrel medic, chickpea, pigeonpea, soybean, common bean, mungbean and adzuki bean) from the reconstructed ancestors of the Galegoid (AGK) and Millettoid (AMK) subfamilies as well as the ancestral legume karyotype (ALK with brackets under the 25 CARs defining 19 proto-chromosomes). Duplication event is shown with a red dot and estimated speciation dates are indicated on tree branches. The modern genomes are illustrated at the bottom with different colors reflecting the origin from ALK (referenced as the ALK painting) or from the inferred Galegoid and Millettoid ancestors (referenced as the AGK and AMK painting).

Pisum genome structure evolution

‘Caméor’ shows a translocation compared to the ancestral Galegoid karyotype and while translocations within Pisum have long been known20,21,22, identifying the chromosomes involved suffered from the lack of clear chromosome identification. Cytological analyses38 identified pairwise crosses between (1) P. sativum, including northern P. humile, (2) P. elatius, including southern P. humile and (3) P. fulvum, which gave rise to chromosomal rings during F1 meiosis and to low hybrid fertility, suggesting that chromosome translocations accompanied Pisum evolution. To reassess these events in the light of the pea genome assembly, we sequenced single-chromosome samples isolated from three accessions that were used by Ben-Ze’ev and Zohary38 (Supplementary Notes). These three lines were considered archetypes of wild species and subspecies: ‘703’ for P. fulvum, ‘721’ for P. elatius and ‘711’ for southern P. humile. DNA amplified from ~40 single chromosomes obtained for each (Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Table 12) was sequenced. Mapping reads from each chromosome sample to the ‘Caméor’ pseudomolecules identified the correspondence between the wild pea and Caméor chromosomes (Fig. 5a,b and Supplementary Fig. 11). All wild pea chromosomes were assigned to ‘Caméor’ chromosomes, but for accessions ‘711’, ‘721’ and ‘703’, reads from chromosome samples corresponding to pseudomolecule 5 mapped only from 0 to 465 Mb of this pseudomolecule and chromosome samples with reads mapping from ~465 Mb to the end of ‘Caméor’ pseudomolecule 5 also mapped to another ‘Caméor’ chromosome (Fig. 5b). For accessions ‘711’ and ‘721’, these mapped predominantly to pseudomolecule 1 of ‘Caméor’, while for ‘703’ they mapped predominantly to pseudomolecule 3 of ‘Caméor’ (Fig. 5b). This indicated a translocation between chromosomes 5 and 1 in ‘711’ and ‘721’ and between chromosomes 5 and 3 in ‘703’ as compared to ‘Caméor’. Investigating synteny between pea and other Galegoid species suggested that the ancestral Pisum karyotype resembled the present P.elatius/humile karyotype rather than the cultivated pea karyotype. Indeed, ‘Caméor’ chromosome 5 is syntenic with M. truncatula chromosome 3 from 0 to 467 Mb and with chromosome 2 of M. truncatula from 467 Mb to its end (Fig. 4). This breakpoint in synteny is close to the translocation point but lies 2 Mb closer to the centromere of chromosome 5. Similarly, a breakpoint in synteny between ‘Caméor’ chromosome 5 and C. arietinum chromosome 5 occurred at this translocation point, with the translocated fragment being syntenic with C. arietinum chromosome 1 (Fig. 4). C. arietinum chromosome 1 and M. truncatula chromosome 2 are syntenic with ‘Caméor’ chromosome 1 and the end of ‘Caméor’ chromosome 5. Considering the AGK reconstruction (Supplementary Fig. 9), the ancestral Pisum chromosome 1 probably contained the translocated fragment (Fig. 5c), as in the P. elatius/humile karyotype. This ancestral chromosome would then have been involved in two independent rearrangements, with the end of chromosome 1 translocated to chromosome 3 in P. fulvum and to chromosome 5 in cultivated pea. What remains unsolved is what role, if any, this breakage may have played in Pisum evolution and adaptation. We note that the repetitive 5 S rRNA gene sequences39 are present at these chromosomal regions (end of chromosome 1, 3 and pericentromeric regions of chromosome 5) suggestive of a role in these translocations.

a, Flow-sorted single chromosomes of ‘Caméor’ were resequenced and reads mapped onto pseudomolecules. The example shows the reads mapping of a ‘Caméor’ chromosome sample corresponding to pseudomolecule 5. The color-codes for chromosomes are as in Fig. 1a. b, Mapping reads of flow-sorted single chromosomes of accessions ‘703’ (P. fulvum), ‘711’ (P. s. humile) and ‘721’ (P. s. elatius)38 identified the correspondence between wild pea chromosomes and the pea genome v.1a pseudomolecules. All chromosomes corresponded one to one to ‘Caméor’ chromosomes except for chromosome 5. Most of the short arm of chromosome 5 (depicted as gray boxes) was associated with other chromosomes in wild Pisum (chromosome 1 in P. s. elatius and P. s. humile, chromosome 3 in P. fulvum). c, Scenario of chromosome evolution. M. truncatula karyotype was used to infer the ancestral Pisum karyotype. In this scenario, two independent translocation events occurred, one leading to present P. fulvum and the other to P. s. sativum karyotypes.

Pisum genetic diversity

Pisum is extremely diverse in terms of phenotypes, and pea breeding could benefit from broad crosses, including introgressions from wild relatives40. Reproductive barriers are not strict among Pisum species and subspecies41. Davis42 proposed that Pisum comprises two species, P. fulvum and P. sativum, with two subspecies: P. s. sativum, which includes all formerly distinguished cultivated types, and P. s. elatius, which includes all formerly distinguished wild types. Although useful, this classification does not clarify the relationships between wild and domesticated forms, or between former taxa. To help refine Pisum taxonomy and evolution, we resequenced the genomes of 36 Pisum accessions representing the range of diversity of the species and one Lathyrus sativus accession as an outgroup. We also included public data from seven Pisum accessions (Supplementary Dataset 7). Because the boundary between wild and cultivated Pisum is blurred by possible introgressions and/or migration, we reassessed the ‘wild’ and ‘cultivated’ status of accessions by scoring germination after imbibing freshly harvested seeds in water for 7 d. Free germination is indeed considered the most important pea domestication trait40. The accessions presented a wide range of phenotypic diversity (Fig. 6a) as shown by principal component analysis (PCA) of plant morphology, phenology, seed productivity and quality traits, which separated wild, landrace and cultivar accessions (Supplementary Dataset 7).

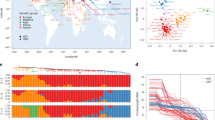

a, PCA of phenotypic traits (Supplementary Notes) discriminating the different Pisum gene pools. In green, modern cultivar accessions; in orange, landrace accessions; in burgundy, wild Pisum elatius and humile accessions; in brown, wild Pisum fulvum accessions, in purple, P. abyssinicum accessions. b, Alleles shared between wild, landrace and modern cultivar accessions. Resequencing data for 43 Pisum and a Lathyrus accessions detected 17.2 M high-quality SNPs, corresponding to 37.6 M alleles. c, Pisum phylogenetic tree was obtained using a subset of 2 M high-quality SNPs and taking Lathyrus sativus as an outgroup. All clades have >95% support (1,000 bootstrap runs). Former Pisum subspecies nomenclature described groups of accessions. Dots on the right-hand side indicate the germination ability of freshly harvested seeds on water, a key trait in pea domestication40. The two P. abyssinicum accessions (*) are cultivated peas but were clustered among wild Pisum accessions.

Whole-genome resequencing reads were mapped onto the pea genome assembly and SNPs were called using BCFtools v.1.6. After filtering, 17,212,424 high-quality SNPs were identified. On 37,591,394 alleles, 51.6% were shared among wild, landrace and cultivar accessions, 25.6% were present only in wild accessions, 3.5% only in landraces and 0.5% only in cultivars (Fig. 6b). Mean nucleotide diversity (π) decreased 1.7-fold between wild accessions (π = 8.2 × 10−4) and landraces (π = 4.9 × 10−4), and 3.4-fold between wild accessions and cultivars (π = 2.4 × 10−4), showing moderate diversity reduction associated with pea domestication and breeding (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. 12). This reduction was accompanied by a high mean pairwise population differentiation (FST) between wild accessions and cultivars (FST = 0.213) and an increase in linkage disequilibrium (LD) across the genome (Supplementary Fig. 13). Mean D Tajima values were significantly positive in wild accessions (D = 0.424) and slightly negative in cultivars, consistent with recent selection (D = −0.038, Supplementary Fig. 12). Phylogenetic analysis of a subset of two million SNPs clustered accessions according to assigned taxon (Fig. 6c): P. fulvum clustered separately from P. sativum accessions. P. sativum accessions clustered according to their cultivated status (wild or cultivated) as well as their geographical origin and usage type (that is, as fodder, dry or fresh seeds). Wild P. s. elatius included former P. elatius and P. humile and cultivated P. s. sativum included P. transcaucasicum, P. asiaticum, P. arvense. P. hortense, but not Pisum abyssinicum. The two P. abyssinicum accessions clustered among the wild P. sativum elatius/humile accessions from Israel while presenting phenotypic attributes of cultivated accessions, including free germination (Fig. 6c). This strengthens the hypothesis of an independent domestication of this taxon from a distinct P. s. elatius43 followed by a migration to Abyssinia possibly through ancient human trading routes44. The chloroplast phylogenetic tree supports this scenario (Supplementary Fig. 14). Notably, the P. elatius accession closest to the cultivated pea was PI639984, an accession collected in 1986 on an abandoned agricultural terrace in Turkey, within the area where pea cultivation emerged.

Seed storage protein gene families

Pea is an important source of dietary proteins for humans and domestic animals. Fractionation of pea seeds into protein, starch and fiber is expanding rapidly in North America and Europe in response to the demand for plant-based protein. Pea seed storage proteins (SSPs) include legumin, vicilin and convicilin globulins and PA1 and PA2 albumins, whose nutritional and technological properties vary according to their amino-acid content and secondary structure45,46. We searched the pea genome assembly for SSP genes using all pea storage protein genes available in UNIPROT (Supplementary Notes) and found 12, 9, 2, 8 and 9 genes encoding legumin, vicilin, convicilin, PA1 and PA2, respectively, as well as a few pseudogenes (Supplementary Dataset 8).

The various SSPs that characterize the pea seed proteome vary in quantity in response to the environment47. Their diversity is magnified by the range of (1) cleavage sites controlling pre-polypeptide cleavage (Supplementary Fig. 15) and (2) transcriptional regulatory regions. Several regulatory motifs, upstream of the SSP genes are presumed to modulate their expression48,49 (Supplementary Dataset 8) dependent on developmental and environmental cues. The RY motif, reported to be required for SSP seed expression50, was found upstream of all but three SSP genes, with some having seven upstream RY motifs. Other motifs were found upstream legumin genes (for example ABRE motif) or vicilin genes (for example ACGT motif). Expression analysis of some SSP genes (Fig. 7a and Supplementary Dataset 8), assessed by microfluidic quantitative PCR, showed that RY motifs were not systematically associated with seed specific expression. Examination of Legumin and Vicilin genes in pea and M. truncatula showed an overall conservation of tandem organization in these two species: clusters of SSP genes were found on syntenic pea and M. truncatula chromosomes, but gene copy number differed (Vicilin and Legumin genes on syntenic Ps3 and Mt7, Convicilin and Legumin genes on syntenic Ps6 and Mt1). Additional gene clusters were found in pea (Vicilin genes on Ps5 and Legumin genes on Ps6 and Ps4, Fig. 7b). Interestingly, all Legumin and Vicilin gene cluster positions in pea corresponded to reported SSP quantity loci51.

a, Legumin gene tree including sequences from the pea genome reference, the UniProt database and the pea gene atlas reveals different clusters distributed on four loci; gene expression in developing seeds was investigated by microfluidic quantitative PCR using specific primers and is shown as color-coded bars (Supplementary Notes). Expression levels were averaged over three biological replicates. b, Organization of genes encoding globulins in the pea and the M. truncatula genomes reveal some conserved features. Chromosome color-codes are as in Fig. 4 showing the syntenic relationships between the pea and M. truncatula genomes. Figures above chromosome bars indicate the size of each chromosome.

Discussion

Pea is an important plant-based protein source for human food and animal feed. This reference genome provides a foundation to elucidate Pisum evolution. The Pisum common ancestor was probably cytogenetically like P. s. elatius, this taxon evolved across the Mediterranean and Middle East40,52 and gave rise in the northern Middle East to P. s. sativum. P. fulvum diverged from the Pisum ancestor in the southern Middle East. P. abyssinicum, an Ethiopian cultivated form, is likely the result of a domestication event from a southern P. s. elatius ancestor and is independent of the domestication of P. s. sativum. Different lines of evidence suggested that the pea genome is evolving at a faster pace than other investigated Leguminosae genomes, potentially through transposon-mediated unequal recombination giving rise to gain or loss of genes, or ectopic double-strand break repair34. Differential expansion and removal of these elements probably shaped genomes throughout the evolution of the Fabeae and notably within Pisum19, suggesting that repetitive elements were major drivers in the evolution of these large genomes. A valuable tool for basic discovery, this high-quality, annotated pea genome sequence will facilitate the characterization of its many known mutants, enhance pea improvement and allow more efficient use of the wide genetic diversity present in the genus.

Methods

Genome sequencing

To enable an optimal assembly of the large (~4.45 Gb) and complex (85% repetitive DNA) pea reference genome, more than 1,300 Gb sequence data (equivalent to 294-fold genome coverage) were generated using DNA extracted from fresh plant material of the French pea cultivar ‘Caméor’ (Supplementary Notes). The data included 100 and 150 bp Illumina reads and PacBio RSII read batches, one N50 = 9,500 kb and another N50 = 15,917 kb. The Illumina reads derived from paired-end libraries with insert sizes of 300, 500, 600 and 800 bp and ten mate-pair libraries with insert sizes between 3 and 17 kb. All sequence data have been deposited in EBI Bioproject PRJEB30482 (Illumina reads) and NCBI Bioproject PRJNA509681 (PacBio reads). Reads 150 bp long, 30-fold genome coverage equivalent, were randomly sampled and genome size was estimated using the GenomeScope program (http://qb.cshl.edu/genomescope/). The estimated genome size of ‘Caméor’ through this method (4.426 Gb) was consistent with previous estimates obtained by flow-cytometry9.

De novo assembly

The pea nuclear genome was assembled into seven pseudomolecules in a step-wise manner. The assembly pipeline is summarized in Supplementary Fig. 2. Shotgun Illumina reads were assembled using SoapdeNovo2 (ref. 53) with 127 nt K-mer and the –R option in the ‘pregraph’ step. Contigs shorter than 500 nt were removed. The remaining contigs were scaffolded with SSPACE 2.0 (ref. 54) using the information captured by mate-pair reads; scaffolds 2 kb or larger, and validated by at least five read pairs, were considered as part of a first draft assembly. This assembly was improved with layers of data from physical maps (Whole-Genome Profiling, WGP), optical maps (Bionano maps), various high-density linkage maps (Genetic maps) and synteny to the M. truncatula genome. The physical map was produced using 295,680 BAC clones of cv. ‘Caméor’ pooled in a multi-dimensional manner. The BAC library was provided by INRA IPS2 and is available at INRA CNRGV (https://cnrgv.toulouse.inra.fr/fr/Banques/Pois); its average BAC insert size is 125 kb and its genome coverage is 9.3×. The BAC DNA was digested with HindIII/MseI; fragments were ligated, amplified by PCR, and sequenced using Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform (100 nt read length). The reads were clustered according to the parental BAC clones’ ID and assembled using FPC software (Keygene N.V.). The physical map was generated according to Gali et al.23 and used to link the scaffolds in the draft assembly into super-scaffolds using MaGuS 1.0 (ref. 55) and the WGP technology56 (Keygene N.V.). Gaps in super-scaffolds were closed with GapCloser57,58 using paired-end, mate-pair and PacBio reads. Super-scaffolds were manually curated for inter and intrachromosomal chimeras (Supplementary notes) using (1) sequences obtained from single chromosomes isolated by flow-cytometry sorting24 (Supplementary Fig. 3, Bioprojects at ENA PRJEB30482, and at NCBI PRJNA507688) and (2) an ultra-high-density genetic map obtained from 162 RILs derived from the cross between ‘Caméor’ × ‘Melrose’ (Pop6)25 and genotyped by skim genotyping-by-sequencing59 (Supplementary Dataset 1, Bioproject PRJNA507685), it is worth noting this map included 468,448 SNPs and represents the highest density genetic map published for pea. Manually corrected scaffolds were integrated into 24,623 super-scaffolds (L50 of 415 Kb; Supplementary Table 2) using an optical map generated from ‘Caméor’ high-molecular weight DNA prepared from the nuclei of young leaves following the IrysPrep protocols (BioNano Genomics; Supplementary Table 3). The curated super-scaffolds were anchored onto high-density genetic maps (derived from populations Pop4, 5, 7, 9 described by Tayeh et al.25, and Pop6’s map described herein) using Allmaps60 to form quasi-chromosomal pseudomolecules. The genome of the model legume M. truncatula v.4 (JCVI61) was used for scaffold orientation when no indication from pea genetic map. The assembly, the pea genome v.1a, is available at https://urgi.versailles.inra.fr/Species/Pisum and at the European Nucleotide Archive (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena/) under project PRJEB31320. A genome JBrowse is available at https://urgi.versailles.inra.fr/Species/Pisum.

Genome annotation: repetitive sequences, gene models and microRNAs

The REPET package v.2.6 (refs. 62,63) was used to identify and annotate repetitive elements in contigs of the pea genome sequence as summarized in Supplementary Fig. 6. A sample from each pseudomolecule, consisting of 700 Mb of the longest scaffolds, served to compare the genome to itself using the pipeline TEdenovo to detect repeats present in at least three copies; 200 Mb were aligned to themselves to identify repeats and RepeatScout was applied to screen the remaining 500 Mb for repetitive low complexity DNA. Identified repeat sequences were clustered by multiple alignments to produce a library of consensus sequences. The repeat consensus sequences were classified according to their characteristics and redundancy using PASTEC64 with Repbase (v.20.05). TEannot then mapped the repeat consensus sequence library produced by TEdenovo against the genome using a two-step approach65. The first step identified consensus sequences with at least one full-copy fragment in the genome. The second step identified the copies of these elements in the genome. The annotation of transposon-protein-domains was refined using DANTE (RepeatExplorer server; https://repeatexplorer-elixir.cerit-sc.cz/) against a custom database66,67. The hits were filtered to cover at least 80% of the reference sequence, minimum identity of 35% and minimum similarity of 45%, allowing for a maximum of three interruptions (frameshifts or stop codons). TE classes were defined according to Wicker et al.68 and TE lineages were defined according to Novak et al.67. The density of TE consensus copies according to their lineages were computed along pseudomolecules and visualized using 1 Mb windows each 500 kb step (Fig. 1). The identification and quantification of repetitive sequences from unassembled Illumina reads were done using RepeatExplorer. The pipeline was run with default parameters, using 3,972,596 paired-end reads (100 nt) as input.

Gene models were predicted de novo using AUGUSTUS v.3.0.3 (ref. 69) and Fgenesh v.7.1.1 (ref. 70) trained on the M. truncatula gene matrix once repetitive DNA was masked using maskfasta v.5.1.22. Protein homology searches (TBLASTN) were done using sequences from: (1) C. arietinum (GA_v.1.0), G. max (275_Wm82.a2.v.1), M. truncatula (Mt4.0 v.1) retaining hits with an E value < 1 × 10−50 and more than 50% of the protein length mapped; (2) UniProt and Swissprot databases retaining hits with an E-value < 1 × 10–20; (3) pea DNA and RNA sequences from IPK and NCBI retaining hits with an E value < 1 × 10–50 and identity criteria ≥98%. Retained sequences were analyzed using Exonerate v.2.2.0 (ref. 71) to generate protein-based gene models. To refine the annotation and identify splice junctions, RNA-seq reads from a series of libraries were aligned to the genome assembly using the ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner STAR (v.STAR_2.4.0j72: Twenty RNA-seq libraries from various plant tissues of ‘Caméor’ at different plant growth stages (188,446,568 reads) are described in Alves-Carvalho et al.73 and 12 highly dense libraries generated from cultivar Kaspa inoculated with isolates of the fungal complex causing Ascochyta blight and mock-inoculated leaf tissue (160,332,071 reads) are described by Turo74 and available in NCBI Bioproject PRJNA510273. A set of assembled transcripts were obtained from the alignments using StringTie (v.1.2.2) (ref. 75) and Trinity-GG (v.2.0.6) (ref. 76). Integration of all above gene models and identification of alternative splice sites were done using the annotation pipeline PASA v.2.0.2, which includes Evidence Modeler v.1.1.1 (ref. 77). The completeness of the gene repertoire was assessed using BUSCO v.3.0.2 (ref. 78).

Putative gene functions were assigned using the best match to SwissProt and TrEMBL databases79. Motifs and domains were searched using InterProScan v.5 (refs. 80,81) against all default protein databases including ProDom, PRINTS, PfamA, SMART, TIGRFAM, PrositeProfiles, HAMAP, PrositePatterns, SITE, SignalP, TMHMM, Panther, Gene3d, Phobius, Coils and CDD. In addition, we used TrapID (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/trapid/), and the PLAZA v.2.5 reference database to assign each transcript to a reference gene family and transfer functional annotation including GO for each transcript. Additionally, an embedded pipeline of EuGene v.4.2 (refs. 82,83)was launched using the same proteins and RNA-seq databases. This annotation procedure yielded 34,137 gene models and was used to curate gene models manually.

For the identification of miRNA, developing seeds of ‘Caméor’ were harvested at two stages (12 d and 22 d after pollination). RNA was purified and small RNA libraries were produced and sequenced according to Lelandais-Briere et al.84. Reads were pooled, trimmed using fastx clipper and a minimum length of 15 nt, and mapped to identify miRNA using ShortStacks (v.3.8.5). ShortStacks classify putative miRNA following several criteria: Y miRNA classification indicates that the miRNA sequence passed all tests including sequencing of the exact miRNA-star, supporting a de novo annotation of a new miRNA family. N15 miRNA classification indicates that the miRNA sequence passed all tests except that the miRNA-star was not sequenced. Y and N15 miRNA were mapped against miRbase v.22 mature miRNA sequences using ssearch36, and only alignment with at least 95% of identity were conserved. For N15 miRNAs, only those with a match to a known plant miRNA were kept. Y miRNAs without annotation were considered newly identified miRNA. Finally, targets were predicted using TargetFinder and kept only if their score was greater than 3. Fifty-nine miRNAs showed at least one putative target (Supplementary Dataset 3b).

Genome structure and evolution

To identify putative paralogous and orthologous gene clusters, protein-coding genes sets from pea and 21 other eudicot species (Supplementary Dataset 4) were analyzed using Orthofinder v.2.1.2 and its defaults parameters85 with the Diamond v.0.9.14 option instead of BLAST86 (Supplementary Notes). Before the analysis, genome assemblies and annotations were subjected to minor amendments to exclude plastid sequence data, inconsistencies in the headings format between fasta and gff3 files, spurious stop codons or sequences with premature stop codons and alternative transcripts. In cases where there were two or more transcript variants, the longest transcript was selected to represent the coding region (input data is summarized in Supplementary Dataset 4). The sequence divergence for all possible pairs of paralogs within each orthogroup was estimated based on pairwise Ks. Protein sequences were aligned using MUSCLE v.3.8.31 (ref. 87) and converted into codon aligned nucleotides using the bioruby-alignment package88. Ks values were calculated through maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) using the ‘codeml’89 and ‘yn00’90 programs in the PAML package91 and using the following parameters: runmode = −2, set-type = 1 (codon sequences), alpha fixed to 0, codonFreq = 2 (F2X4). For that purpose, we created an in-memory sqlite database including the whole-genome assemblies and annotations to identify pairs of paralogs based on the Orthogroups.csv file. For all Ks distribution histograms, the x axes were drawn on a log-scale with non-transformed Ks values to represent the decreasing relative importance of differences as the Ks value increases resulting from the stochastic nature and saturation of Ks calculations92. The range of values, 0.01–50, were binned into 400 interval-bins. To reduce the exponential effect of spurious homologs on background noise, we filtered the data based on orthogroup size. The histograms in Supplementary Fig. 7 represent paralogs pairs in orthogroups of 8 to 20 genes or less: for each species, the orthogroup size was determined based on the genome multiples for events leading to the eudicot divergence onwards (Supplementary Dataset 4).

Based on both homology and synteny, we further investigated the paleohistory of legume genomes. An evolutionary scenario was obtained following the method described in Pont et al.93 based on synteny relationships identified between between pea (P. sativum), peanut diploid ancestor (Arachis duranensis,94), lotus (Lotus japonicus11), barrel medic (Medicago truncatula10), chickpea (Cicer arietinum95), pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan96), soybean (Glycine max12), common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris97), mungbean (Vigna radiata98) and adzuki bean (Vigna angularis99). Genomes were aligned to define conserved or duplicated gene pairs based on alignment parameters, groups of conserved genes were clustered or chained into synteny blocks (excluding blocks with less than five genes) corresponding to independent sets of blocks sharing orthologous relationships in modern species. Then, conserved groups of gene-to-gene adjacencies defining identical chromosome-to-chromosome relationships between all the extant genomes were merged into CARs. CARs were merged into protochromosomes based on partial synteny observed between a subset of the investigated species. The ancestral karyotype is a ‘median’ or ‘intermediate’ genome consisting of proto-chromosomes defining a clean reference gene order, common to the extant species investigated. From the reconstructed ancestral karyotype an evolutionary scenario was then inferred taking into account the fewest number of genomic rearrangements, which may have occurred between the inferred ancestors and the modern genomes (Supplementary Notes).

Pisum diversity

Genomic resequencing data of 44 accessions were used to study the pea genome diversity (Supplementary Dataset 7). Sixteen genotypes, including Caméor, were resequenced as described in Tayeh et al.25, as part of the ANR program GENOPEA (Bioproject PRJNA285605). Another 16 genotypes were chosen25,52,100 and resequenced in the Pisdom Burgundy region PARI project (FABER M. Siol, Bioproject PRJNA431567). Nuclear DNA was extracted using the Floraclean Plant DNA isolation kit as recommended by MP Biomedicals (http:/www.mpbio.com). A quality control was performed for all DNA samples with Quant-iT PicoGreen (Invitrogen) and by measuring absorbance and checking electrophoretic profile on agarose gel. Illumina paired-end shotgun indexed libraries were prepared from one µg of DNA per genotype, using the TruSeq DNA PCR-free LT Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina Inc., https://www.illumina.com/). Paired-end sequencing 2 × 100 sequencing by synthesis (SBS) cycles was performed on a HiSeq 2000, TruSeq V.3 chemistry according to manufacturer’s instructions. Additionally, three genotypes (DSP, 90–2131, Kiflica; Bioproject PRJNA509279) were sequenced by a commercial company (NovoGene) using Illumina HiSeq, paired-end 150 bp from 350 bp insert DNA libraries and three accessions (‘703’, ‘711’, ‘721’) were resequenced at GENOSCOPE on an HiSeq2500 using the Nextera Mate Pair Sample preparation kit of Illumina (Bioproject PRJEB30482) as described above for the genome sequencing. All pea resequenced genotypes, except Zhongwan6 for which we had no seeds, were evaluated in the glasshouse for classical growth and development traits (Supplementary Notes and Supplementary Dataset 1). Two pots per accessions and six seeds per pot were sown in February 2017 in 7 l pots. In total, 59 phenotypic traits were scored on the 44 genotypes, including seed protein composition traits. Germination tests were conducted on freshly harvested seeds (five seeds per accession, three replicates) and mean germination rates were calculated.

Resequencing data for the 43 accessions of Pisum and the accession of Lathyrus sativus were mapped onto the pea genome v.1a assembly using BWA MEM101, keeping only unique mapping with a quality higher or equal to 30. Optical duplicates were removed with PICARD tools (http://picard.sourceforge.net/). Altogether, 95,326,251 SNPs were called using BCFtools v.1.6 (ref. 101) mpileup and call. All callings supported by less than three reads were reimputed. All markers that were homozygous or heterozygous in ‘Caméor’ as compared to the reference were deleted using SNPSift102. We produced two different datasets depending on the type of analysis to be conducted. For phylogenetic analysis, 2,026,659 SNPs with less than five missing data and ten heterozygotes were filtered using vcftools103 and plink104 (Phylogeny SNP dataset). For diversity analysis, 17,212,608 SNPs with less than ten missing data and ten heterozygotes were filtered (Diversity SNP dataset). In this dataset, accessions L180 and Zhongwan6 were removed.

The ‘Phylogeny’ SNP dataset was used to build a phylogenetic tree of the 44 accessions using IQ-Tree v.1.6 (ref. 105). TVM + R10 was selected as the best model for a maximum likelihood tree using Modelfinder106. The tree was inferred with 1000 replicates of ultrafast likelihood bootstrap107 and SH-aLRT test to obtain bootstrap branch support values. The number of alleles present in the different Pisum groups were computed using the ‘Diversity’ dataset. An in-house script was used to transform SNP information into alleles coded in an allele dose 012 format. The VennCounts function of the R package limma108 was used to calculate Venn diagrams for each group.

Resequencing reads obtained for wild, landrace and a few cultivar accessions were mapped on the genome using NGM by default109 (Supplementary Notes). Counts were computed using FeatureCounts110 on specific associated lineage domains. The reads mapping onto TE domains were counted and normalized by dividing the number of counts on a specific domain by the total number of counts on all TE domains and by the total number of occurrences of each domain in the pea genome v.1a assembly per million.

Statistical tests were performed as follows. The variation of TE representation among the different Pisum species and subspecies was tested using proc GLM (SAS Institute). Different models were tested by analysis of variance (ANOVA): Model1 tested the different TE representation between P. fulvum, P. sativum wild and P. s. sativum groups; Model 2, between P. fulvum, P. sativum wild, P.sativum landraces and P.sativum cultivars; and Model 3 between P. fulvum, P. sativum wild, P. abyssinicum, P. sativum landraces and P.sativum cultivars. Counts were normalized by dividing the number of counts on a specific domain by the total number of counts on all TE domains and by the total number of occurrence of each domain in the pea genome v.1a assembly per million. For Model 2, mean least square predicted values of normalized mapped reads’ count and their standard deviations were computed and two-tailed t-tests were performed for eight selected TE lineages.

Translocation analyses

To identify chromosome translocations, we sequenced single chromosomes isolated by flow sorting from the three accessions P. fulvum ‘703’, P. sativum elatius ‘721’ and P. sativum southern humile ‘711’ characterized by Ben-Ze’ev and Zohary38 and compared the sequences with the sequence assembly of P. sativum cv. Caméor. Preparation of suspensions of intact mitotic chromosomes, flow cytometric analysis and sorting was done according to Neumann et al.24. For each genotype, 84 chromosomes were flow-sorted and single-chromosome DNA amplification was done (Supplementary Notes). Of these, a total of 137 DNA samples were selected and sequenced (Supplementary Notes). To identify the pseudomolecule that each sample corresponded to, we mapped the chromosome sequence data onto the genome assembly of P. sativum cv. Caméor. This identified the correspondence between chromosome samples and pseudomolecules.

Seed storage proteins annotation

A list of storage protein sequences was set up by combining sequences retrieved from the pea gene atlas, UNIPROT and NCBI and searched for homologies in the pea genome assembly (Supplementary Dataset 4). Candidate sequences were manually curated using protein alignments, RNA-seq data and gene models by euGene. Known regulatory motifs were searched in the 5′ region of the identified gene models (Supplementary Dataset 4). Best homology matches were search for in Uniprot Genbank and the M. truncatula genome v.4. To assess seed storage protein gene expression, total RNA from seeds was extracted using an RNeasy plant mini kit (Qiagen, www.qiagen.com) after grinding plant tissue in liquid nitrogen using a pestle and mortar. cDNA were prepared according to Gallardo et al.111. Other cDNAs were produced as described in Alves-Carvalho et al.73. High-throughput real-time quantitative PCR was performed using the Biomark microfluidic system from Fluidigm according to manufacturer’s protocol. Primers used are listed in Supplementary Dataset 4. Expression was normalized as in Alves-Carvalho et al.73.

Reporting Summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All raw sequencing data are available at the European Nucleotide Archive (PRJEB30482) and as an NCBI BioProject (PRJNA507685, PRJNA507688, PRJNA509681, PRJNA510273, PRJNA285605, PRJNA431567, PRJNA509279). The pea genome v.1a reference assembly is available for download and JBrowse at https://urgi.versailles.inra.fr/Species/Pisum. The genome is also available at the European Nucleotide Archive under project PRJEB31320.

References

Burstin, J., Gallardo, K., Mir, R. R., Varshney, R. K. & Duc, G. Improving protein content and nutrition quality, in Biology and Breeding of Food Legumes (eds Pratap, A. & Kumar, J.) 314–328 (CAB International, 2011).

Guillon, F. & Champ, M. M.-J. Carbohydrate fractions of legumes: uses in human nutrition and potential for health. Br. J. Nutr. 88, S293–S306 (2002).

Dahl, W. J., Foster, L. M. & Tyler, R. T. Review of the health benefits of peas (Pisum sativum L.). Br. J. Nutr. 108, S3–S10 (2012).

Foschia, M., Horstmann, S. W., Arendt, E. K. & Zannini, E. Legumes as functional ingredients in gluten-free bakery and pasta products. Ann. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 8, 75–96 (2017).

Nemecek, T. et al. Environmental impacts of introducing grain legumes into European crop rotations. Eur. J. Agron. 28, 380–393 (2008).

Crews, T. E. & Peoples, M. B. Legume versus fertilizer sources of nitrogen: ecological tradeoffs and human needs. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 102, 279–297 (2004).

Poore, J. & Nemecek, T. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science 360, 987–992 (2018).

Zohary, D. & Hopf, M. Domestication of Plants in the Old World (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, 2000).

Doležel, J. et al. Plant genome size estimation by flow cytometry: inter-laboratory comparison. Ann. Bot. 82, 17–26 (1998).

Young, N. D. et al. The Medicago genome provides insight into the evolution of rhizobial symbioses. Nature 480, 520–524 (2011).

Sato, S. et al. Genome structure of the legume, Lotus japonicus. DNA Res. 15, 227–239 (2008).

Schmutz, J. Genome sequence of the palaeopolyploid soybean. Nature 463, 178–183 (2010).

Mendel, G. Versuche über Pflanzenhybriden. Verhandlungen des naturforschenden Vereines in Brünn, Bd. IV für das Jahr 1865. Abhandlungen, 3–47 (1866).

Ellis, T. H. N., Hofer, J. M. I., Timmerman-Vaughan, G. M., Coyne, C. J. & Hellens, R. P. Mendel, 150 years on. Trends Plant Sci. 16, 590–596 (2011).

Tayeh, N. et al. Genomic tools in pea breeding programs: status and perspectives. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 1037 (2015).

Ellis, T. H. N. & Poyser, S. J. An integrated and comparative view of pea genetic and cytogenetic maps. New Phytol. 153, 17–25 (2002).

Flavell, R. B., Bennett, M. D., Smith, J. B. & Smith, D. B. Genome size and the proportion of repeated nucleotide sequence DNA in plants. Biochem. Genet. 12, 257–269 (1974).

Murray, M. G., Peters, D. L. & Thompson, W. F. Ancient repeated sequences in the pea and mung bean genomes and implications for genome evolution. J. Mol. Evol. 17, 31–42 (1981).

Macas, J. et al. In depth characterization of repetitive DNA in 23 plant genomes reveals sources of genome size variation in the legume tribe Fabeae. PLoS One 10, e0143424 (2015).

Hammarlund, C. & Håkansson, A. Parallelism of chromosome ring formation, sterility and linkage in Pisum. Hereditas 14, 97–98 (1930).

Sansome, E. Segmental interchange lines in Pisum sativum. Nature 139, 113 (1937).

Lamm, R. & Miravalle, R. J. A translocation tester set in Pisum. Hereditas 45, 417–440 (1959).

Gali, K. K. et al. Development of a sequence-based reference physical map of pea (Pisum sativum L.). Front. Plant Sci. 10, 323 (2019).

Neumann, P., Pozárková, D., Vrána, J., Doležel, J. & Macas, J. Chromosome sorting and PCR-based physical mapping in pea (Pisum sativum L.). Chromosome Res. 10, 63–71 (2002).

Tayeh, N. et al. Development of two major resources for pea genomics: the GenoPea 13.2K SNP Array and a high density, high resolution consensus genetic map. Plant J. 84, 1257–1273 (2015).

Neumann, P. et al. Stretching the rules: monocentric chromosomes with multiple centromere domains. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002777 (2012).

Pellicer, J., Hidalgo, O., Dodsworth, S. & Leitch, I. Genome size diversity and its impact on the evolution of land plants. Genes 9, 88 (2018).

Bennett, M. C. & Leitch, I. J. Plant DNA C-values Database release 6.0 (FAIRsharing.org, 2012); https://doi.org/10.25504/FAIRsharing.7qexb2

Hane, J. K. et al. A comprehensive draft genome sequence for lupin (Lupinus angustifolius), an emerging health food: insights into plant–microbe interactions and legume evolution. Plant Biotechnol. J. 15, 318–330 (2017).

Blixt, S. Mutation genetics in Pisum. Agric. Hort. Genet. 30, 1–293 (1972).

Cannon, S. et al. Multiple polyploidy events in the early radiation of nodulating and nonnodulating legumes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 193–210 (2015).

Bowers, J. E., Chapman, B. A., Rong, J. & Paterson, A. H. Unravelling angiosperm genome evolution by phylogenetic analysis of chromosomal duplication events. Nature 422, 433–438 (2003).

Lavin, M., Herendeen, P. S. & Wojciechowski, M. F. Evolutionary rates analysis of Leguminosae implicates a rapid diversification of lineages during the tertiary. Syst. Biol. 54, 575–594 (2005).

Li, S. F. et al. Chromosome evolution in connection with repetitive sequences and epigenetics in plants. Genes 8, 290 (2017).

De Vega, J. J. et al. Red clover (Trifolium pratense L.) draft genome provides a platform for trait improvement. Sci. Rep. 5, 17394 (2015).

Lee, C., Yu, D., Choi, H. K. & Kim, R. W. Reconstruction of a composite comparative map composed of ten legume genomes. Genes Genom. 39, 111–119 (2017).

Kamphuis, L. G. et al. The Medicago truncatula reference accession A17 has an aberrant chromosomal configuration. New Phytol. 174, 299–303 (2007).

Ben-Ze'ev, N. & Zohary, D. Species relationships in the genus Pisum L. Isr. J. Bot. 22, 73–91 (1973).

Neumann, P., Nouzová, M. & Macas, J. Molecular and cytogenetic analysis of repetitive DNA in pea (Pisum sativum L.). Genome 44, 716–728 (2001).

Ladizinsky, G. & Abbo, S. (eds.) The Pisum genus. in The Search for Wild Relatives of Cool Season Legumes 55–68 (Springer, 2015).

Kosterin, O. E. & Bogdanova, V. S. Reciprocal compatibility within the genus Pisum L. as studied in F1 hybrids: 1. Crosses involving P. sativum L. subsp. sativum. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 62, 691–709 (2015).

Davis, P. H. in Flora of Turkey and the East Aegean Islands Vol. 3 (ed P. H. Davis) 370–373 (Edinburgh Univ., 1970).

Weeden, N. F. Domestication of pea (Pisum sativum L.): the case of the Abyssinicum pea. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 515 (2018).

Pagani, L. et al. Ethiopian genetic diversity reveals linguistic stratification and complex influences on the Ethiopian gene pool. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 91, 83–96 (2012).

Gabriel, I. et al. Variation in seed protein digestion of different pea (Pisum sativum L.) genotypes by cecectomized broiler chickens: 1. Endogenous amino acid losses, true digestibility and in vitro hydrolysis of proteins. Livest. Sci. 113, 251–261 (2008).

Rubio, L. A. et al. Characterization of pea (Pisum sativum) seed protein fractions. J. Sci. Food Agric. 94, 280–287 (2014).

Bourgeois, M. et al. Dissecting the proteome of pea mature seeds reveals the phenotypic plasticity of seed protein composition. Proteomics 9, 254–271 (2009).

Casey, R. & Domoney, C. in Seed Proteins (eds Shewry, P. R. & Casey, R.) 171–208 (Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1999).

Yoshino, M., Nagamatsu, A., Tsutsumi, K. I. & Kanazawa, A. The regulatory function of the upstream sequence of the β-conglycinin α subunit gene in seed-specific transcription is associated with the presence of the RY sequence. Genes Genet. Syst. 81, 135–141 (2006).

Yamamoto, S., Nishihara, M., Morikawa, H., Yamauchi, D. & Minamikawa, T. Promoter analysis of seed storage protein genes from Canavalia gladiata DC. Plant Mol. Biol. 27, 729–741 (1995).

Bourgeois, M. et al. A PQL (protein quantity loci) analysis of mature pea seed proteins identifies loci determining seed protein composition. Proteomics 11, 1581–1594 (2011).

Smýkal, P. et al. Genomic diversity and macroecology of the crop wild relatives of domesticated pea. Sci. Rep. 7, 17384 (2017).

Luo, R. et al. SOAPdenovo2: an empirically improved memory-efficient short-read de novo assembler. Gigascience 1, 18 (2012).

Boetzer, M., Henkel, C. V., Jansen, H. J., Butler, D. & Pirovano, W. Scaffolding pre-assembled contigs using SSPACE. Bioinformatics 27, 578–579 (2011).

Madoui, M.-A. et al. MaGuS: a tool for quality assessment and scaffolding of genome assemblies with whole genome profilingTM Data. BMC Bioinformatics 17, 115 (2016).

van Oeveren, J. et al. Sequence-based physical mapping of complex genomes by whole genome rofiling. Genome Res. 21, 618–625 (2011).

Li, R. et al. The sequence and de novo assembly of the giant panda genome. Nature 463, 311–317 (2010).

Li, R. et al. De novo assembly of human genomes with massively parallel short read sequencing. Genome Res. 20, 265–272 (2010).

Bayer, P. E. et al. High-resolution skim genotyping by sequencing reveals the distribution of crossovers and gene conversions in Cicer arietinum and Brassica napus. Theor. Appl. Genet. 128, 1039–1047 (2015).

Tang, H. et al. ALLMAPS: robust scaffold ordering based on multiple maps. Genome Biol. 16, 3 (2015).

Tang, H. et al. An improved genome release (version Mt4.0) for the model legume Medicago truncatula. BMC Genomics 27, 312 (2014).

Flutre, T., Duprat, E., Feuillet, C. & Quesneville, H. Considering transposable element diversification in de novo annotation approaches. PloS One 6, e16526 (2011).

Quesneville, H. et al. Combined evidence annotation of transposable elements in genome sequences. PLoS Comput. Biol. 1, e22 (2005).

Hoede, C. et al. PASTEC: an automatic transposable element classification tool. PLoS ONE 9, e91929 (2014).

Jamilloux, V., Daron, J., Choulet, F. & Quesneville, H. De novo annotation of transposable elements: tackling the fat genome issue. Proc. IEEE 105, 474–481 (2107).

Novák, P., Neumann, P. & Macas, J. Graph-based clustering and characterization of repetitive sequences in next-generation sequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics 11, 378 (2010).

Novák, P., Neumann, P., Pech, J., Steinhaisl, J. & Macas, J. RepeatExplorer: a Galaxy-based web server for genome-wide characterization of eukaryotic repetitive elements from next-generation sequence reads. Bioinformatics 29, 792–793 (2013).

Wicker, T. et al. A unified classification system for eukaryotic transposable elements. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8, 973–982 (2007).

Keller, O. et al. A novel hybrid gene prediction method employing protein multiple sequence alignments. Bioinformatics 6, 757–763 (2011).

Solovyev, V. et al. Automatic annotation of eukaryotic genes, pseudogenes and promoters. Genome Biol. 7, S10 (2006).

Slater, G. S. & Birney, E. Automated generation of heuristics for biological sequence comparison. BMC Bioinformatics 6, 31 (2005).

Dobin, A. et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29, 15–21 (2013).

Alves-Carvalho, S. Full-length de novo assembly of RNA-seq data in pea (Pisum sativum L.) provides a gene expression atlas and gives insights into root nodulation in this species. Plant J. 84, 1–19 (2015).

Turo, C. J. Genomic Analysis of Fungal Species Causing Ascochyta Blight in Field Pea. PhD thesis, Curtin Univ. (2016).

Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotech. 33, 290 (2015).

Grabherr, M. G. et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644–652 (2011).

Haas, B. J. et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the program to assemble spliced alignments. Genome Biol. 9, R7 (2008).

Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–3212 (2015).

The UniProt Consortium. Ongoing and future developments at the Universal Protein Resource. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, D214–D219 (2011).

Jones, P. et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30, 1236–1240 (2014).

Cock, P. J. A., Grüning, B. A., Paszkiewicz, K. & Pritchard, L. Galaxy tools and workflows for sequence analysis with applications in molecular plant pathology. Peer J. 1, e167 (2013).

Foissac, S. et al. Genome annotation in plants and fungi: EuGene as a model platform. Curr. Bioinf. 3, 87–97 (2008).

Badouin, H. et al. The sunflower genome provides insights into oil metabolism, flowering and Asterid evolution. Nature 546, 148–152 (2017).

Lelandais-Brière, C. et al. Genome-wide Medicago truncatula small RNA analysis revealed novel microRNAs and isoforms differentially regulated in roots and nodules. Plant Cell 21, 2780–2796 (2009).

Emms, D. M. & Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: solving fundamental biases in whole genome comparisons dramatically improves orthogroup inference accuracy. Genome Biol. 16, 157 (2015).

Buchfink, B., Xie, C. & Huson, D. H. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 12, 59–60 (2014).

Edgar, R. C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797 (2004).

Bonnal, R. J. P. et al. Biogem: an effective tool-based approach for scaling up open source software development in bioinformatics. Bioinformatics 28, 1035–1037 (2012).

Goldman, N. & Yang, Z. A codon-based model of nucleotide substitution for protein-coding DNA sequences. Mol. Biol. Evol. 11, 725–736 (1994).

Yang, Z. & Nielsen, R. Estimating synonymous and nonsynonymous substitution rates under realistic evolutionary models. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17, 32–43 (2000).

Yang, Z. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol. Biol. Evol. 24, 1586–1591 (2007).

Vanneste, K., de Peer, Van & Maere, Y. S. Inference of genome duplications from age distributions revisited. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 177–190 (2013).

Pont, C. et al. Paleogenomics: reconstruction of plant evolutionary trajectories from modern and ancient DNA. Genome Biol. 20, 29 (2019).

Bertioli, D. J. et al. The genome sequences of Arachis duranensis and Arachis ipaensis, the diploid ancestors of cultivated peanut. Nat. Genet. 47, 438–446 (2015).

Varshney, R. K. et al. Draft genome sequence of chickpea (Cicer arietinum) provides a resource for trait improvement. Nat. Biotech. 31, 240–246 (2013).

Singh, N. K. et al. The first draft of the pigeonpea genome sequence. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 21, 98–112 (2012).

Schmutz, J. et al. A reference genome for common bean and genome-wide analysis of dual domestications. Nat. Genet. 46, 707–713 (2014).

Kang, Y. J. et al. Genome sequence of mungbean and insights into evolution within Vigna species. Nat. Commun. 5, 5443 (2014).

Kang, Y. J. et al. Draft genome sequence of adzuki bean Vigna angularis. Sci. Rep. 5, 8069 (2015).

Siol, M. et al. Patterns of genetic structure and linkage disequilibrium in a large collection of pea germplasm. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genet. 7, 2461–2471 (2017).

Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–2079 (2009).

Cingolani, P. et al. Using Drosophila melanogaster as a model for genotoxic chemical mutational studies with a new program, SnpSift. Front. Genet. 3, 35 (2012).

Danecek, P. et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 27, 2156–2158 (2011).

Purcell, S. et al. PLINK: A Tool Set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 81, 559–575 (2007).

Nguyen, L. T. et al. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 32, 268–274 (2014).

Kalyaanamoorthy, S. et al. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat. Methods 14, 587–589 (2017).

Hoang, D. T. et al. UFBoot2: improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 35, 518–522 (2017).

Ritchie, M. E. et al. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 4, 3 e47 (2015).

Sedlazeck, F. J., Rescheneder, P. & Von Haeseler, A. NextGenMap: fast and accurate read mapping in highly polymorphic genomes. Bioinformatics 29, 2790–2791 (2013).

Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923–930 (2013).

Gallardo, K. et al. A combined proteome and transcriptome analysis of developing Medicago truncatula seeds evidence for metabolic specialization of maternal and filial tissues. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 6, 2165–2179 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We thank F. Jacquin, M. Chabert-Martinello, C. Rond-Coissieux, M. Touratier, M. Naudet-Huart and F. Naudé for their expert assistance in preparing plant and DNA materials and in phenotyping accessions. We are thankful to V. Jamilloux (REPET) and J. Gouzy (Eugene) for their support, to Z. Dubská, M. Karafiátová and J. Weiserová for assistance in flow-cytometry chromosome sorting, to V. Vernoud for providing seed tissues for transcriptomics, to E. Bonin for the high-throughput q-PCR assays, to E. Marquand, A. Chauveau and D. Brunel for the generation and management of resequencing 32 accessions, to CEA-IG/CNG for providing access EPGV group to its DNA quality control service and their Illumina sequencers, to E. van der Vossen (Keygene) for the development of the physical map, to H. Bergès for providing the BAC library, to D. Pouchnik and M. Wildung for PacBio library preparation and sequencing, to C. Cruaud for miRNA sequencing, to M. Siol and P. Smykal for the choice of resequenced accessions, to M. Siol for initiating the PARI Pisdom project, to N. Hostáková for her assistance during initial phases of repeat analysis, to B. Noel for data submission, to Raphael Flores for making the legume synteny data publicly available, to R. Thompson, N. Tayeh and K. Avia for discussions and reviewing the manuscript, and to V. Malécot for helpful discussions on taxonomy. This project was supported by ANR France-Génomique (no. ANR-10-INBS-09; Illumina genome sequencing, chromosome resequencing, assembly), ANR Genopea (no. ANR-09-GENM-026; resequencing), Région Bourgogne Franche-Comté (Projet PARI Pisdom; resequencing), European FP7 project ‘Legumes for the Agriculture of Tomorrow’ (no. 613551; genetic mapping), Czech Science Foundation (no. 17-09750S, centromere and repeat analysis), Czech Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports ERDF project ‘Plants as a tool for sustainable global development’, no. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_019/0000827 (chromosome sorting and optical maps), AVRIL (France; annotation and mapping), Saskatchewan Pulse Growers (Canada, WGP), USA Dry Pea & Lentil Council, Northern Pulse Growers (USA, PacBio sequencing), the Australian Grains Research and Development Corporation (no. GRDC CUR00021, skim-GBS and chromosome sequencing), Australian Research Council (nos. LP160100030 and LP140100537 to D.E. and J.Batley) and the AUS-Aid Australian Awards for Africa Scholarship (to C.J.T. supervised by J.L.). J.L., R.A.S., C.J.T., D.E., P.E.B. and H.T.L. were supported by resources provided by the Pawsey Supercomputing Centre with funding from the Australian Government and the Government of Western Australia. P.E.B. acknowledges the support of the Forrest Research Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.K., G.A., M.A.M., J.D., J.M., D.E., T.D.W., C.J.C., J.L. and J.Burstin formed part of the International Pea Genome Sequencing Consortium steering committee and established the experimental outline. G.A. supervised DNA material production, A. Klein supervised plant material production and phenotyping, C.J.C. and J. Burstin supervised the germplasm choice. P.W. and K.L. generated Illumina genomic sequence data and single-chromosome sequencing data. D.M., R.M. and C.J.C. generated PacBio genomic sequence data. C.J.T. and J.L. conducted transcriptome assays and generated RNA-seq data. M.A.M., P.W., L.d’A. and J.M.A. conducted the genome assembly. J.K., A. Kougbeadjo, G.A. and J. Burstin curated and improved genome assembly. J.K. and C.F. produced the genome annotation. A.Bendahmane supervised the generation of the BAC library. P.C., J.V., J.D. performed flow cytometric sorting of single chromosomes and amplified their DNA for sequencing. H.T., Z.M., C.B. and J.D. made the associated optical maps. G.A., K.G. and J.Burstin performed the seed storage protein gene analyses. P.E.B., H.T.L., J.Batley and D.E. generated the skim-GBS map and ‘Caméor’ single-chromosome sequencing. A.Bérard, M.C.L.P., K.L., C.J.C., D.M., R.M. generated re-sequencing data. K.K.G., B.T. and T.D.W. procured the whole-genome profiling data. R.A.S., J.K., A. Kougbeadjo, J.L. and J.Burstin contributed to the whole-genome evolution studies. C.H. and J.S. reconstructed the legume paleo-genome. C.B. and W.B. developed the whole-genome optical maps. M.T., G.A. and K.G. performed the miRNA analyses. J.K., P.Novak, I.V., P.Neumann, J.Burstin and J.M. analyzed repetitive DNA. I.V., P.Neumann and J.M. performed FISH assays. N.E. contributed to data analysis. N.M., M.T. and J.K. set up the JBrowse platform. M.F. built the genetic maps. J.K., J.M., C.J.C., J.S., J.L. and J.Burstin wrote the paper. G.A., K.G, P.W., J.D., C.B., D.E., B.T., T.D.W., D.M., R.M. and N.E. edited the paper. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–15, Tables 1–12 and Note

Supplementary Datasets 1,3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8