Abstract

Macroscale analogues1,2,3 of microscopic spin systems offer direct insights into fundamental physical principles, thereby advancing our understanding of synchronization phenomena4 and informing the design of novel classes of chiral metamaterials5,6,7. Here we introduce hydrodynamic spin lattices (HSLs) of ‘walking’ droplets as a class of active spin systems with particle–wave coupling. HSLs reveal various non-equilibrium symmetry-breaking phenomena, including transitions from antiferromagnetic to ferromagnetic order that can be controlled by varying the lattice geometry and system rotation8. Theoretical predictions based on a generalized Kuramoto model4 derived from first principles rationalize our experimental observations, establishing HSLs as a versatile platform for exploring active phase oscillator dynamics. The tunability of HSLs suggests exciting directions for future research, from active spin–wave dynamics to hydrodynamic analogue computation and droplet-based topological insulators.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Change history

05 October 2021

This Article was amended to include links to the Supplementary Videos.

References

Kane, C. L. & Lubensky, T. C. Topological boundary modes in isostatic lattices. Nat. Phys. 10, 39–45 (2014).

Chen, B. G.-g., Upadhyaya, N. & Vitelli, V. Nonlinear conduction via solitons in a topological mechanical insulator. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 13004–13009 (2014).

Nash, L. M. et al. Topological mechanics of gyroscopic metamaterials. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 14495–14500 (2015).

Strogatz, S. H. From Kuramoto to Crawford: exploring the onset of synchronization in populations of coupled oscillators. Physica D 143, 1–20 (2000).

Rechtsman, M. C. et al. Optimized structures for photonic quasicrystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 073902 (2008).

van Zuiden, B. C. et al. Spatiotemporal order and emergent edge currents in active spinner materials. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 12919–12924 (2016).

Soni, V. et al. The odd free surface flows of a colloidal chiral fluid. Nat. Phys. 15, 1188–1194 (2019).

Fort, E. et al. Path-memory induced quantization of classical orbits. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 17515–17520 (2010).

Coey, J. M. D. Magnetism and Magnetic Materials (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010).

Watson, J. D. & Crick, F. H. C. The structure of DNA. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 18, 123–131 (1953).

Weinberg, S. The Quantum Theory of Fields Vol. 2 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1996).

Baltz, V. et al. Antiferromagnetic spintronics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 015005 (2018).

Chumak, A. V. et al. Magnon spintronics. Nat. Phys. 11, 453–461 (2015).

Maurer, P. C. et al. Room-temperature quantum bit memory exceeding one second. Science 336, 1283–1286 (2012).

Süsstrunk, R. & Huber, S. D. Observation of phononic helical edge states in a mechanical topological insulator. Science 349, 47–50 (2015).

Schneider, U. et al. Metallic and insulating phases of repulsively interacting fermions in a 3D optical lattice. Science 322, 1520–1525 (2008).

Cheuk, L. W. et al. Quantum-gas microscope for fermionic atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 193001 (2015).

Buluta, I., Asshab, S. & Nori, F. Natural and artificial atoms for quantum computation. Rep. Prog. Phys. 74, 104401 (2011).

Gross, C. & Bloch, I. Quantum simulations with ultracold atoms in optical lattices. Science 357, 995–1001 (2017).

Dieny, B. et al. Opportunities and challenges for spintronics in the microelectronics industry. Nat. Electron. 3, 446–459 (2020).

Biktashev, V. N., Barkley, D. & Biktasheva, I. V. Orbital motion of spiral waves in excitable media. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 058302 (2010).

Totz, J. F. et al. Spiral wave chimera states in large populations of coupled chemical oscillators. Nat. Phys. 14, 282–285 (2018).

Wioland, H. et al. Ferromagnetic and antiferromagnetic order in bacterial vortex lattices. Nat. Phys. 12, 341–345 (2016).

Nishiguchi, D. et al. Engineering bacterial vortex lattice via direct laser lithography. Nat. Commun. 9, 4486 (2018).

Riedel, I. H., Kruse, K. & Howard, J. A self-organized vortex array of hydrodynamically entrained sperm cells. Science 309, 300–303 (2005).

Souslov, A. et al. Topological sound in active-liquid metamaterials. Nat. Phys. 13, 1091–1094 (2017).

Sáenz, P. J. et al. Spin lattices of walking droplets. Phys. Rev. Fluids 3, 100508 (2018).

Couder, Y. et al. Dynamical phenomena: walking and orbiting droplets. Nature 437, 208 (2005).

Bush, J. W. M. Pilot-wave hydrodynamics. Ann. Rev. Fluid Mech. 47, 269–292 (2015).

Lindner, B. et al. Effects of noise in excitable systems. Phys. Rep. 392, 321–424 (2004).

Cumin, D. & Unsworth, C. P. Generalising the Kuramoto model for the study of neuronal synchronization in the brain. Physica D 226, 181–196 (2007).

Matheny, M. H. et al. Exotic states in a simple network of nanoelectromechanical oscillators. Science 363, eaav7932 (2019).

Dörfler, F. & Bullo, F. Synchronization in complex networks of phase oscillators: a survey. Automatica 50, 1539–1564 (2014).

Protière, S., Boudaoud, A. & Couder, Y. Particle-wave association on a fluid interface.J. Fluid Mech. 554, 85–108 (2006).

Eddi, A. et al. Information stored in Faraday waves: the origin of a path memory. J. Fluid Mech. 674, 433–463 (2011).

Moláček, J. & Bush, J. W. M. Drops walking on a vibrating bath: towards a hydrodynamic pilot-wave theory. J. Fluid Mech. 727, 612–647 (2013).

Sáenz, P. J., Cristea-Platon, T. & Bush, J. W. M. A hydrodynamic analog of Friedel oscillations. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay9234 (2020).

Ruderman, M. A. & Kittel, C. Indirect exchange coupling of nuclear magnetic moments by conduction electrons. Phys. Rev. 96, 99–102 (1954).

Ronellenfitsch, H. et al. Inverse design of discrete mechanical metamaterials. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 095201 (2019).

Lagendijk, A., Van Tiggelen, B. & Wiersma, D. S. Fifty years of Anderson localization. Phys. Today 62, 24 (2009).

Oza, A. U., Rosales, R. R. & Bush, J. W. M. Hydrodynamic spin states. Chaos 28, 096106 (2018).

Oza, A. U., Rosales, R. R. & Bush, J. W. M. A trajectory equation for walking droplets: hydrodynamic pilotwave theory. J. Fluid Mech. 737, 552–570 (2013).

Labousse, M. et al. Self-attraction into spinning eigenstates of a mobile wave source by its emission backreaction. Phys. Rev. E 94, 042224 (2016).

Perrard, S. et al. Self-organization into quantized eigenstates of a classical wave-driven particle. Nat. Commun. 5, 3219 (2014).

Eddi, A. et al. Level splitting at macroscopic scale. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 264503 (2012).

Harris, D. M. & Bush, J. W. M. Droplets walking in a rotating frame: from quantized orbits to multimodal statistics. J. Fluid Mech. 739, 444–464 (2014).

Oza, A. U. et al. Pilot-wave dynamics in a rotating frame: on the emergence of orbital quantization. J. Fluid Mech. 744, 404–429 (2014).

Sáenz, P. J., Cristea-Platon, T. & Bush, J. W. M. Statistical projection effects in a hydrodynamic pilot-wave system. Nat. Phys. 14, 315–319 (2018).

Eddi, A. et al. Archimedean lattices in the bound states of wave interacting particles. Europhys. Lett. 87, 56002 (2009).

Eddi, A., Boudaoud, A. & Couder, Y. Oscillating instability in bouncing droplet crystals. Europhys. Lett. 94, 20004 (2011).

Thomson, S. J., Couchman, M. M. P. & Bush, J. W. M. Collective vibrations of confined levitating droplets. Phys. Rev. Fluids 5, 083601 (2020).

Thomson, S. J., Durey, M. & Rosales, R. R. Collective vibrations of a hydrodynamic active lattice. Proc. R. Soc. A 476, 20200155 (2020).

Couchman, M. M. P. & Bush, J. W. M. Free rings of bouncing droplets: stability and dynamics. J. Fluid Mech. 903, A49 (2020).

Nachbin, A. Walking droplets correlated at a distance. Chaos 28, 096110 (2018).

Nachbin, A. Kuramoto-like synchronization mediated through Faraday surface waves. Fluids 5, 226 (2020).

Whitham, G. B. Linear and Nonlinear Waves (Wiley, 1974).

Douady, S. Experimental study of the Faraday instability. J. Fluid Mech. 221, 383–409 (1990).

Harris, D. M. & Bush, J. W. M. Generating uniaxial vibration with an electrodynamic shaker and external air bearing. J. Sound Vibrat. 334, 255–269 (2015).

Faraday, M. On a peculiar class of acoustical figures and on certain forms assumed by groups of particles upon vibrating elastic surfaces. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 121, 299–340 (1831).

Harris, D. M., Liu, T. & Bush, J. W. M. A low-cost, precise piezoelectric droplet-on-demand generator. Exp. Fluids 56, 83 (2015).

Bush, J. W. M., Oza, A. U. & Moláček, J. The wave-induced added mass of walking droplets. J. Fluid Mech. 755, R7 (2014).

Turton, S. E. Theoretical Modeling of Pilot-wave Hydrodynamics. PhD thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2020).

Labousse, M. & Perrard, S. Non-Hamiltonian features of a classical pilot-wave dynamics. Phys. Rev. E 90, 022913 (2014).

Cristea-Platon, T., Sáenz, P. J. & Bush, J. W. M. Walking droplets in a circular corral: quantisation and chaos. Chaos 28, 096116 (2018).

Tadrist, L. et al. Faraday instability and subthreshold Faraday waves: surface waves emitted by walkers. J. Fluid Mech. 848, 906–945 (2018).

Galeano-Rios, C. A. et al. Ratcheting droplet pairs. Chaos 28, 096112 (2018).

Couchman, M. M. P., Turton, S. E. & Bush, J. W. M. Bouncing phase variations in pilot-wave hydrodynamics and the stability of droplet pairs. J. Fluid Mech. 871, 212–243 (2019).

Faria, L. M. A model for Faraday pilot waves over variable topography. J. Fluid Mech. 811, 51–66 (2017).

Filatrella, G., Nielsen, A. H. & Pedersen, N. F. Analysis of a power grid using a Kuramoto-like model. Eur. Phys. J. B 61, 485–491 (2008).

Rohden, M. et al. Self-organized synchronization in decentralized power grids. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 064101 (2012).

Chen, P. & Wu, K.-A. Subcritical bifurcations and nonlinear balloons in Faraday waves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 3813–3816 (2000).

Périnet, N., Juric, D. & Tuckerman, L. S. Alternating hexagonal and striped patterns in Faraday surface waves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 164501 (2012).

Pucci, G. et al. Non-specular reflection of walking droplets. J. Fluid Mech. 804, R3 (2016).

Pucci, G. et al. Walking droplets interacting with single and double slits. J. Fluid Mech. 835, 1136–1156 (2018).

Harris, D. M. et al. The interaction of a walking droplet and a submerged pillar: from scattering to the logarithmic spiral. Chaos 28, 096105 (2018).

Damiano, A. P. et al. Surface topography measurements of the bouncing droplet experiment. Exp. Fluids 57, 163 (2016).

Diep, H. T. Frustrated Spin Systems (World Scientific, 2004).

Qi, X.-L. & Zhang, S.-C. Topological insulators and superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1057–1110 (2011).

Biktasheva, I. V. & Biktashev, V. N. Wave–particle dualism of spiral waves dynamics. Phys. Rev. E 67, 026221 (2003).

Biktasheva, I. V. et al. Computation of the drift velocity of spiral waves using response functions. Phys. Rev. E 81, 066202 (2010).

Azhand, A., Totz, J. F. & Engel, H. Three-dimensional autonomous pacemaker in the photosensitive Belousov–Zhabotinsky medium. Europhys. Lett. 108, 10004 (2014).

Totz, J. F., Engel, H. & Steinbock, O. Spatial confinement causes lifetime enhancement and expansion of vortex rings with positive filament tension. New J. Phys. 17, 093043 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the NSF through CMMI-1727565 (J.W.M.B. and P.J.S.) and DMS-1719637 (R.R.R.), MIT Solomon Buchsbaum Research Fund (J.D.), and CNRS Momentum programme (G.P.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.J.S. conceived the study, led the experimental developments and the writing of the paper, and contributed to the theoretical modelling. S.E.T. and R.R.R. contributed to the theoretical modelling. G.P. contributed to the conception and execution of the preliminary experiments. A.G. contributed to the preliminary experiments. J.D. contributed to the theoretical modelling and the writing of the paper. J.W.M.B. contributed to the conception of the experiments and theory, and to writing the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature thanks Michael Shats and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

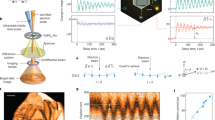

Extended Data Fig. 1 Schematic of the experimental set-up.

The test section was mounted on an optical table and vibrated vertically by an electromagnetic shaker. The shaker was connected to the bath by a thin steel rod coupled with a linear air bearing. The forcing acceleration was monitored by two piezoelectric accelerometers. The bath was enclosed within a transparent acrylic chamber to ensure that ambient air currents did not affect the experiments. A d.c. motor housed inside the hollow air bearing enabled system rotation.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Experimental spin flips.

a−e, Snapshots at different times illustrate a typical spin-flip event arising in a 1D spin lattice (Supplementary Video 6). At each time, the panels at left are colour-coded according to the instantaneous spin Si (same colour map as in Fig. 1d), while those on the right depict the recent walker trajectories, colour-coded according to the local speed. Perturbed by the wave fields emitted by its neighbours, the middle walker initially follows an elliptical path. The length of the minor axis decreases until the walker trajectory essentially becomes a straight line across the well centre. Subsequently, the process is reversed, resulting in the walker rotating in the opposite sense. The three walkers shown are part of the 1D antiferromagnetic lattice described in Fig. 1h with γ/γF = 86.0%.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Wave coupling.

a, Experimental visualization of the wave field generated by a single walker in a 1D lattice with the same geometry as in Fig. 1h and γ/γF = 92.0%. The submerged wells can be identified as the regions with a different shade of grey. b, Superposition of the wave field shown in a and the zeros of the drop-centred Bessel function \({J}_{0}({k}_{\text{F}}|{\bf{x}} \mbox{-} {{\bf{x}}}_{{\rm{i}}}|)\). c, Wave field of a bouncer computed with the theoretical model developed previously68 for walkers over variable topography. The bouncer is located at (x, y) = (3D/8, 0) in a 2D square lattice with the same well diameter D and centre-to-centre separation L as in a and γ/γF = 88.0%. Solid blue lines denote the submerged wells and dashed lines the zeros of a Bessel function J0 centred at the drop position.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Emergent order for varying lattice spacing.

a, b, The dependence of the average spin correlation, ⟨χ⟩ (a) and the mean phase difference, ⟨Δϕ⟩ (b) on the lattice spacing, L, as predicted by the Bessel model (equation (16)) with τ = 0.4 s, ω0 = 3.3 s−1, and \( {\mathcal F} \) = 70 s−2. The average droplet-induced wave field, which is approximated by a Bessel function J0(kFL), centred in the neighbouring well at L = 0, is provided for comparison in a. c, d, Dominant (c) and subdominant (d) synchronization modes for the corresponding sections (A–D) in a, b.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Emergent order for varying bath acceleration.

Comparison of the experimentally observed average spin correlation, ⟨χ⟩, with the predictions of the Bessel model (equation (16)) and the generalized Kuramoto model (equation (23)). Solid lines are fits resulting from smoothing the piecewise linear plot given by connecting the points. Bessel model parameters: L = 17.7 mm, r = 1.8 mm, λF = 2π/kF = 5.1 mm. The interaction parameter \( {\mathcal F} \) is varied across the range 70 < \( {\mathcal F} \) < 130 s−2 and transformed back to γ/γF using the relation from Extended Data Table 1. To simplify the simulations, we fix the relaxation time to be τ = 0.1 s and the natural angular frequency to be ω0 = 3.3 s−1, values consistent with experimental observation (Fig. 1c). The effective walker mass is set to mw = 1.65m, in line with prior work61. GK model parameters: α is varied over the range 8.5 < α < 15 s−2, while maintaining β < 0 and a constant ratio |β/α| = 0.3. By dividing the expressions for α and β in equations (25), (26) by a factor of two, in accordance with the mismatch between the GK and Bessel models discussed in Supplementary Fig. 3, the minimum ⟨χ⟩ predicted by the GK model emerged in the vicinity of γc.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Emergent order in large 2D square lattices.

Simulations of the Bessel model (equation (16)) and the generalized Kuramoto model (equation (23)) for a 50 × 50 square lattice demonstrate the emergence of antiferromagnetic and ferromagnetic order in 2D for various lattice spacings and bath accelerations. a, The lattice spacing determines the emergent antiferromagnetic (ADM+) or ferromagnetic (FM+) order in a manner predicted by our reduced theory (equation (24)). b, c, Specifically, preferred in-phase rotation between neighbouring pairs can be clearly observed in the antiferromagnetic AFM+ (b), and ferromagnetic FM+ (c) regimes. We note that b and c correspond to simulations of the Bessel model with the spacings indicated on a. d, The emergent in-phase antiferromagnetic order (AFM+) as a function of bath acceleration. Bessel model parameters in a: τ = 0.1 s, ℱ = 72 s−2, 16.8 ≤ L ≤ 19 mm, ω0 = 3.3 s−1, and λF = 4.95 mm. Bessel model parameters in d are the same as in a, but with L = 17.1 mm and the interaction parameter varies across the range 65 ≤ ℱ ≤ 85 s−2, which is transformed back to γ/γF using the relation from Extended Data Table 1. GK model parameters in d: α is varied over the range 9.5 < α < 13 s−2 while maintaining β < 0 and a constant ratio |β/α| = 0.07, τ = 0.2 s and ω0 = 3.3 s−1. In all cases, each data point results from averaging 50 simulations of 600 s each, to ensure statistical significance.

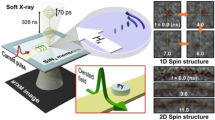

Extended Data Fig. 7 Emergent order for different vertical bouncing synchronizations and lattice geometries.

a, Oblique view of a 2D spin lattice where the walker in the centre is bouncing vertically in-phase and out-of-phase with its left and right neighbours, respectively. b, Average spin correlation for lattices with the same geometry as those described in Fig. 1 when the walkers all bounce in phase (blue, result presented in text), out of phase (green), or have randomly distributed bouncing phases (red). Vertically in-phase pairs promote in-phase orbital antiferromagnetic order (AFM+), whereas vertically out-of-phase pairs promote out-of-phase orbital antiferromagnetic order (AFM−). A random distribution of vertical phases thus leads to competing orbital synchronization modes, which has an effect on the emergent spin correlation. Solid lines are fits resulting from smoothing the piecewise linear plot given by connecting the points. c, Triangular HSLs with a lattice spacing tuned to promote antiferromagnetic order can be used to investigate frustration effects.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Emergent collective order in simulations.

Simulations of square HSLs with the theoretical model developed previously68 is used to explore collective order in 2D. a, b, For appropriate lattice spacings, in-phase ferromagnetic order FM+ (a) and in-phase antiferromagnetic order AFM+ (b) are simulated. Left, schematic; middle, wave field and walker’s trajectories; right, time evolution of the orbital phases.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Model tunability.

Proof-of-concept simulations performed with the model developed previously68 illustrate the tunability and potential for future research of HSLs. Left, schematic; middle, wave field and drop trajectories; and right, orbital phase evolution. a, An HSL tuned to promote FM+ along the horizontal direction, but AFM+ across vertical pairs. b, FM+ lattice geometry with a random vertical and horizontal shift ±ε in the position of each well. c, FM+ lattice geometry with two drop sizes (and so, two walker speeds). d, FM+ lattice geometry with coupling strength controlled locally through the thickness of the liquid layer.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Figures 1-4.

Supplementary Video 1 Hydrodynamic spin lattices

Experiments demonstrate that a walking droplet self-propelling on the surface of a vibrating liquid interface may be trapped by a submerged circular well at the bottom of the fluid bath, leading to clockwise or counter-clockwise angular motion centred on the well. When a collection of such wells is arranged in a 1D or 2D lattice geometry, a thin fluid layer between wells enables wave-mediated interactions between neighbouring droplets.

Supplementary Video 2 Anti-ferromagnetic order

Experiments with a periodic 1D lattice with lattice spacing L=17.7 mm demonstrate the emergence of anti-ferromagnetic order in which walkers tend to rotate in the opposite sense relative to their nearest neighbours.

Supplementary Video 3 Ferromagnetic order

Experiments with a periodic 1D lattice with lattice spacing L=13.2 mm result in ferromagnetic order in which droplets tend to rotate in the same sense as their neighbours.

Supplementary Video 4 Inducing global polarization through applied rotation

Rotating the hydrodynamic spin system induces a transition from anti-ferromagnetic to ferromagnetic order.

Supplementary Video 5 Emergent order in 2D square lattices

Experiments with 2D square lattices show the emergence of anti-ferromagnetic order in the absence of applied bath rotation, and a polarization transition as the bath rotation is increased.

Supplementary Video 6 Spin flip

A typical spin flip event as observed in experiments. The three droplets shown are part of the 1D antiferromagnetic lattice detailed in Fig. 1h.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sáenz, P.J., Pucci, G., Turton, S.E. et al. Emergent order in hydrodynamic spin lattices. Nature 596, 58–62 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03682-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03682-1

This article is cited by

-

Polygonal patterns of Faraday water waves analogous to collective excitations in Bose–Einstein condensates

Nature Physics (2024)

-

Bidirectional wave-propelled capillary spinners

Communications Physics (2023)

-

Steady-state statistics, emergent patterns and intermittent energy transfer in a ring of oscillators

Nonlinear Dynamics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.