Abstract

Following its emergence in late 2019, the spread of SARS-CoV-21,2 has been tracked by phylogenetic analysis of viral genome sequences in unprecedented detail3,4,5. Although the virus spread globally in early 2020 before borders closed, intercontinental travel has since been greatly reduced. However, travel within Europe resumed in the summer of 2020. Here we report on a SARS-CoV-2 variant, 20E (EU1), that was identified in Spain in early summer 2020 and subsequently spread across Europe. We find no evidence that this variant has increased transmissibility, but instead demonstrate how rising incidence in Spain, resumption of travel, and lack of effective screening and containment may explain the variant’s success. Despite travel restrictions, we estimate that 20E (EU1) was introduced hundreds of times to European countries by summertime travellers, which is likely to have undermined local efforts to minimize infection with SARS-CoV-2. Our results illustrate how a variant can rapidly become dominant even in the absence of a substantial transmission advantage in favourable epidemiological settings. Genomic surveillance is critical for understanding how travel can affect transmission of SARS-CoV-2, and thus for informing future containment strategies as travel resumes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The pandemic of COVID-19, which is caused by SARS-CoV-2, is the first pandemic for which the spread of a viral pathogen has been globally tracked in near real-time using phylogenetic analysis of viral genome sequences3,4,5. SARS-CoV-2 genomes continue to be generated at a rate far greater than for any other pathogen, and more than 950,000 full genomes were available in the Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data (GISAID) database as of April 20216.

In addition to tracking viral spread, these sequences have been used to monitor mutations that might change the transmission, pathogenesis, or antigenic properties of the virus. One mutation in particular, D614G in the spike protein (Nextstrain clade 20A and its descendants), seeded large outbreaks in Europe in early 2020 and subsequently dominated outbreaks in the Americas, thereby largely replacing previously circulating lineages. This rapid rise led to the suggestion that this variant is more transmissible, which has since been corroborated by phylogenetic7,8 and experimental evidence9,10. Subsequently, three variants of concern—Alpha/501Y.V1/B.1.1.7 (refs. 11,12), Beta/501Y.V2/B.1.351 (refs. 13,14) and Gamma/501Y.V3/P.1 (ref. 15), which have increased transmissibility and/or can partially escape neutralization—were identified at the end of 2020.

Following the global dissemination of SARS-CoV-2 in early 20203, intercontinental travel dropped markedly. Within Europe, however, travel (particularly holiday travel) resumed in the summer. Here we report on SARS-CoV-2 variant 20E (EU1), with an A222V mutation in the spike protein, which first rose in frequency in Spain in early summer 2020 and subsequently spread to multiple locations in Europe, rising in frequency in parallel. This variant and a second variant (20A.EU2, with an S477N mutation in the spike protein) accounted for the majority of sequences in Europe in the autumn of 2020.

European variants in summer 2020

Figure 1 shows a time-scaled phylogeny of sequences sampled in Europe up to the end of November 2020 and their global context, highlighting the variants discussed here. A cluster of sequences in clade 20A has an additional mutation (spike A222V), shown in orange. We designate this cluster as 20E (EU1) (this cluster consists of lineage B.1.177 and its sublineages16).

Left, the tree shows a representative sample of isolates from Europe coloured by clade and by the variants highlighted in this paper. Clade 20A and its daughter clades 20B and 20C (yellow) carry mutations S:D614G. Variant 20E (EU1) (orange), with mutation S:A222V on a S:D614G background, emerged in early summer 2020 and became common in many European countries in autumn 2020. A separate variant (20A.EU2; blue) with mutation S:S477N became prevalent in France. Right, the proportion of sequences belonging to each variant (up to the end of November 2020) per country. Tree and visualization were generated using the Nextstrain platform4 (see Methods). Map data copyright Google, INEGI (2021).

In addition to 20E (EU1), a variant (20A.EU2; blue in Fig. 1) with several amino acid substitutions, including S:S477N, became common in some European countries, particularly France (Extended Data Fig. 1). The S:S477N substitution has arisen multiple times independently, for example in clade 20F, which dominated the outbreak in Oceania during the southern-hemisphere winter. Residue S477 is close to the receptor binding site (Extended Data Fig. 2) and forms part of the epitope recognized by the S2E12 and C102 neutralizing antibodies17,18.

Several other smaller clusters, defined by the spike mutations D80Y, S98F and N439K, have also been found in multiple countries (Extended Data Table 1, Extended Data Fig. 1). Whereas none of these has reached the prevalence of 20E (EU1) or 20A.EU2, some have attracted attention in their own right: S:N439K is present in two larger clusters found across Europe19 and arose several times independently. Updated phylogenies and further analyses of these and other variants are available at https://covariants.org/.

Characterization of S:A222V

Our analysis here focuses on the variant 20E (EU1), with substitution A222V in the spike protein’s domain A (also referred to as the N-terminal domain (NTD))18,20,21 (Extended Data Fig. 2). This mutation is not known to influence receptor binding or membrane fusion by SARS-CoV-2. However, mutations can sometimes have long-range effects on protein conformation or stability.

To investigate whether the A222V mutation affects the conformation of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein, we used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to test binding of the mutant ectodomain by the benchmark COVID-19 convalescent patient plasma from the National Institute for Biologicals Standards and Control, and by neutralizing monoclonal antibodies that recognize the receptor-binding domain (RBD; antibodies S2E12 and S309)18,22,23 and the NTD (antibody 4A8)24. The dose–response curves were indistinguishable for the extodomain trimers of SARS-CoV-2 2PS (a prefusion-stabilized form of the spike protein with two proline substitutions) and SARS-CoV-2 2P A222V D614G S (Extended Data Fig. 3a–d), aligning with results from a recent study25. Collectively, these data indicate that the A222V substitution does not appreciably affect the antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein.

To test whether the A222V mutation had an obvious functional effect on the ability of the spike protein to mediate viral entry, we produced lentiviral particles pseudotyped with spike either containing or lacking the A222V mutation on the background of the D614G mutation and deletion of the end of its cytoplasmic tail. Lentiviral particles with the A222V mutant spike had slightly higher titres than those without (mean 1.3-fold higher), although the difference was not statistically significant after normalization by p24 concentration (Extended Data Fig. 3e–h). Therefore, A222V does not lead to the same large increases in the titres of spike-pseudotyped lentivirus as was observed for the D614G mutation7,10 However, this small effect must be interpreted cautiously, as the effects of mutations on viral transmission in humans are not always paralleled by measurements made in simplified experimental systems.

In addition to S:A222V, 20E (EU1) has the amino acid mutations ORF10:V30L, N:A220V and ORF14:L67F. However, there is little evidence for the functional relevance of ORF10 and ORF1426,27. Different mutations between positions 180 and 220 in the nucleocapsid (N) protein are observed in almost every major lineage of SARS-CoV-2 and we are not aware of any evidence that these mutations have important phenotypic consequences. Therefore, we examined epidemiological and phylogenetic evidence to explain the spread of 20E (EU1).

Early observations of 20E (EU1)

The earliest sequences of 20E (EU1) were found in samples collected on 20 June 2020 (seven in Spain and one in the Netherlands). By the end of August, 20E (EU1) sequences had also been detected in Belgium, Switzerland, France, Denmark, the UK, Germany, Latvia, Sweden, Norway and Italy. Sequences of 20E (EU1) from Hong Kong, Australia, New Zealand, and Singapore—presumably representing exports from Europe—were first detected between mid-August and mid-October (Supplementary Table 1).

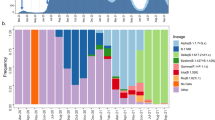

The proportion of sequences that matched 20E (EU1) in several countries is plotted by ISO week in Fig. 2. This variant first rose in frequency in Spain, reaching around 50% prevalence within a month of the first sequence being detected before rising to 80%. In many European countries, there was a gradual rise starting in mid-July before prevalence settled at a level between 15 and 80% in September or October.

We include the eight countries for which there are at least 200 sequences from 20E (EU1), as well as Norway and France, to illustrate points in the text. The symbol size indicates the number of available sequences by country and time point in a nonlinear manner. In most countries we observe a gradual rise from mid-July that settles to a plateau. By contrast, Norway experienced a sharp peak in summer but seems to have brought cases down quickly, although they began to increase again in September. When the last data point included only very few sequences, it has been dropped for clarity. Frequencies are smoothed using a Gaussian with σ = 1 week.

Expansion and spread across Europe

To quantify the spread of 20E (EU1) across Europe, we constructed a phylogeny (Extended Data Fig. 4a) based on data from samples collected before 30 September 2020 and available from GISAID in January 2021 (see Methods). The phylogeny is collapsed to group diversity that might stem from within-country transmission into sectors of the pie charts (Extended Data Fig. 4b–d) for selected countries. The tree indicates that 20E (EU1) harbours substantial diversity, and most major genotypes have been observed in many European countries. As it is unlikely that phylogenetic patterns sampled in multiple countries arose independently, it is reasonable to assume that most mutations observed in the tree arose once and were carried (possibly multiple times) between countries. Throughout July and August 2020, Spain had a higher per capita incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection than most other European countries (Extended Data Fig. 5) and 20E (EU1) was much more prevalent in Spain than elsewhere, suggesting that Spain is the likely origin of most introductions of 20E (EU1) into other countries.

Epidemiological data from Spain indicate that the earliest sequences in the cluster are associated with two known outbreaks in the northeast of the country. The variant seems to have initially spread among agricultural workers in Aragon and Catalonia, then moved into the local population, where it was able to travel to the Valencia region and on to the rest of the country.

Most basal genotypes have been observed both in Spain and in many other countries, suggesting that they were repeatedly exported. However, the 795 sequences from Spain included in Extended Data Fig. 4a are not likely to represent the full diversity. Variants found only outside Spain may reflect diversity that arose in other countries, or may represent diversity that was present but not sampled in Spain (particularly as some European countries, such as the UK and Denmark, sequence a high proportion of cases). Despite limitations in sampling, Extended Data Fig. 4a clearly shows that most major genotypes in this cluster were distributed to multiple countries, suggesting that identical genotypes were introduced into many countries. This is consistent with the large number of introductions estimated from travel data, discussed below. Although initial introductions of the variant probably originated from Spain, cases of 20E (EU1) outside Spain surpassed those in Spain in late September, and later cross-border transmissions are likely to have originated in other countries (Extended Data Fig. 5b). The Supplementary Information includes a discussion of travel restrictions in selected European countries and the associated patterns of 20E (EU1) introductions.

Extended Data Figure 4e shows the distribution of sequence clusters compatible with onward transmission within countries outside Spain, and highlights two different patterns. Norway and Iceland, for example, seem to have had only a small number of introductions over the summer that led to substantial further spread. In Extended Data Fig. 4a, the majority of sequences from these countries fall into one sector and the remainder are singletons or very small clusters that did not spread. However, later sequences in Norway or Iceland often cluster more closely with diversity in non-Spanish European countries, which may suggest that further introductions came from third countries (see 20E (EU1) Nextstrain build online: https://covariants.org/variants/20A.EU1).

By contrast, countries such as Switzerland, the Netherlands, and the UK have sampled sequences that correspond to a large number of independent introductions and include most major genotypes observed in Spain.

No evidence for transmission advantage

During a dynamic outbreak, it is particularly difficult to be certain of whether a particular variant is increasing in frequency because it has an intrinsic advantage, or because of epidemiological factors28. In fact, it is a tautology that every novel large cluster must have grown recently, and multiple lines of independent evidence are required to demonstrate intrinsically elevated transmission potential.

Initially, 20E (EU1) was dispersed across Europe mainly by travellers to and from Spain. Many EU and Schengen-area countries opened their borders to other countries in the bloc on 15 June 2020. Travel resumed quickly and peaked during July and August (Fig. 3). The number of confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection in Spain rose from around 10 cases per 100,000 inhabitants per week in early July to 100 cases per 100,000 inhabitants per week in late August, while case numbers remained low in most of Europe during this time. To investigate whether repeated imports are sufficient to explain the rapid rise in frequency of 20E (EU1) and its displacement of other variants, we first estimated the number of expected introductions of 20E (EU1) on the basis of the number of visitors from a particular country to different provinces of Spain and the incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in those provinces. Taking reported incidence in the provinces at face value and assuming that returning tourists have a similar incidence, we expect 380 introductions of 20E (EU1) into the UK over the summer (6 July to 27 September; see Supplementary Table 2 and Fig. 3 for tourism summaries29 and departure statistics30). Similarly, for Germany and Switzerland we would expect around 320 and 90 introductions of 20E (EU1), respectively. We then created a simple model that also incorporates the incidence in the country to which travellers are returning and the onward spread of imported infections with 20E (EU1) to estimate the frequency of 20E (EU1) in countries across Europe over time (Fig. 3). This model assumes that 20E (EU1) spread at the same rate as other variants in the resident countries and predicts that the frequencies of 20E (EU1) would start to rise in July, continue to rise during August, and be stable thereafter, consistent with observations in many countries (Fig. 3b).

a, Travel from Spain to other European countries resumed in July 2020 (although it was low compared to previous years). Assuming that travel returnees were infected at the average incidence of the Spanish province they visited and transmitted the virus at the rate of their resident population, imports from Spain are expected to account for between 2 and 12% of SARS-CoV-2 infections after the summer. Traveller incidence was calculated using case and travel data at the level of provinces. Note that this model accounts only for the contribution of summer travel and that stochastic fluctuations and other variants after the summer will result in further variation in the frequency of 20E (EU1). See Methods and Extended Data Fig. 8 for geographic detail.

Although the shape of the expected frequency trajectories from imports in Fig. 3b is consistent with observations, this naive import model underestimates the final observed frequency of 20E (EU1) by between 1- and 12-fold, depending on the country (Extended Data Fig. 6). This discrepancy might be due to either intrinsically faster transmission of 20E (EU1) or underestimation of introductions. Underestimates might result from country-specific reporting, such as the relative ascertainment rate in source and destination populations, and the fact that risk of exposure and onward transmission are likely to be increased by travel-related activities both abroad, en route, and at home. Furthermore, the incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in holiday destinations might not be well-represented by the provincial averages used in the model. For example, during the first wave in spring 2020, some ski resorts had exceptionally high incidence and contributed disproportionately to the dispersal of SARS-CoV-231,32. The facts that the rapid increase in the frequency of 20E (EU1) slowed or stopped in most countries after the summer travel period and that it did not fully replace other variants are consistent with import-driven dynamics with little or no competitive advantage.

The notion that an underestimated incidence in travel returnees rather than faster spread of 20E (EU1) is the major contributor to the above discrepancy is supported by the fact that German authorities reported about 2.2 times as many cases with suspected infection in Spain as the model predicts (982 reported versus 452 estimated from 6 July to 13 September, regardless of variant; Extended Data Fig. 7a). Switzerland reported 131 infections in travel returnees, while the model predicts 130. After we adjusted imports for the 37% of Swiss case reports without exposure information, we find that the model underestimates introductions 1.6-fold. Tourists from countries with small (1–4-fold) and large (8–12-fold) discrepancies tended to visit different destinations in Spain (Extended Data Figs. 6, 7c–e), which further suggests that the underestimation of incidence in travel returnees is determined by destination and behaviour.

To investigate the possibility that 20E (EU1) grew faster than other variants following its introduction, we identified introductions of both 20E (EU1) and non-20E (EU1) variants into Switzerland and their downstream Swiss transmission chains. These data suggest that there were 34 or 291 introductions of 20E (EU1), depending on the criterion used to assign sequences to putative transmission chains (see Methods). Phylodynamic estimates of the effective reproductive number (Re) over time for introductions of 20E (EU1) and for other variants (Extended Data Fig. 8) suggest a tendency for 20E (EU1) introductions to transiently grow faster. This transient signal of faster growth, however, is more readily explained by behavioural differences and increased travel-associated transmission than intrinsic differences in the virus. We repeated the phylodynamic analysis with a pan-European set of putative introductions and found similar patterns to those observed for Switzerland.

These patterns are also consistent with the fact that Swiss cases with likely exposure in Spain tended to be in younger individuals (median 30 years, interquartile range (IQR) 23–42.25 years) than cases acquired in Switzerland (median 35 years, IQR 24–51 years). Younger individuals tend to have more contacts than older people33,34. The association with particular demographics will decay rapidly, and with it any associated increased transmission inferred by phylodynamics.

Most introductions of 20E (EU1) are expected to have occurred towards the end of summer, when incidence in Spain was rising and return travel volume peaked. For countries such as Belgium, the comparatively high incidence of non-20E (EU1) variants at this time and, therefore, a relatively low impact of imported variants (Extended Data Fig. 5) might explain why 20E (EU1) remained at low frequencies in these countries despite high-volume travel to Spain.

Case numbers across Europe started to rise rapidly around the same time as the 20E (EU1) variant started to become prevalent in multiple countries (Extended Data Fig. 5). However, countries where 20E (EU1) was rare (Belgium, France, Czech Republic; Extended Data Fig. 1) saw similarly rapid increases, which suggests that this rise was not driven by any particular lineage and that 20E (EU1) has no substantial difference in transmissibility. Furthermore, in Switzerland Re increased in the autumn by a comparable amount for the 20E (EU1) and non-20E (EU1) variants (Extended Data Fig. 8). Although we cannot rule out the possibility that 20E (EU1) had a slight transmission advantage compared to other variants circulating at the time, most of its spread is explained by epidemiological factors., The arrival of autumn and seasonal factors are a more plausible explanation for the resurgence of cases35.

Discussion

The rapid spread of 20E (EU1) and other variants have underscored the importance of a coordinated and systematic sequencing effort to detect, track, and analyse emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. This becomes even more urgent with the recent detection of several variants of concern11,12,13,14,15. It is only through multi-country genomic surveillance that it has been possible to detect and track 20E (EU1) and other variants.

When a new variant is observed, policy-makers need a rapid assessment of whether the new variant increases the transmissibility of the virus, evades pre-existing immunity or has different clinical properties36. In the case of 20E (EU1), none of these seem to have changed substantially, making it an important example of how travel combined with large regional differences in prevalence can lead to substantial and rapid shifts in the variant distribution without a marked transmission advantage. Such shifts—driven predominantly by epidemiological factors—are more likely in a low-incidence setting, where a large fraction of cases can result from introductions. By contrast, the variant of concern Alpha/501Y.V1/B.1.1.7 spread across Europe in late 2020, at which time most countries, including the UK (where it first rose to prominence), reported a high incidence. In such high-incidence settings, travel alone cannot explain a rapid rise in frequency, and the dynamics point to a bona fide transmission advantage. In-depth characterization of a spectrum of such dynamics (no substantial advantage for 20E (EU1), moderate advantage for the D614G mutation8, and a strong transmission advantage for Alpha/501Y.V1/B.1.1.711,12 and Beta/501Y.V213) will facilitate the assessment of emerging variants in the future.

Finally, our analysis highlights that countries should carefully consider their approach to travel when large-scale international movement resumes across Europe. We show that holiday travel in summer 2020 resulted in unexpectedly high levels of introductions and onward spread across Europe. Whether the 20E (EU1) variant described here spread rapidly owing to a transmission advantage or to epidemiological factors alone, its repeated introduction and rise in prevalence in multiple countries implies that the summer travel guidelines and restrictions were generally not sufficient to prevent onward transmission of introductions. Travel precautions such as quarantine should, in principle, have prevented the spread of SARS-CoV-2 infections acquired abroad, but in practice failed to have the desired effect. Although long-term travel restrictions and border closures are neither tenable nor desirable, the identification of better ways to reduce the risk of introducing variants, and to ensure that those that are introduced do not spread widely, will help countries to maintain their (often hard-won) low levels of SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

Methods

Data reporting

No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. The experiments were not randomized and the investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Phylogenetic analysis

We used the Nextstrain pipeline for our phylogenetic analyses (https://github.com/nextstrain/ncov/)4. In brief, we aligned sequences using mafft37, subsampled sequences (see below), added sequences from the rest of the world for phylogenetic context based on genomic proximity, reconstructed a phylogeny using IQTree38 and inferred a time-scaled phylogeny using TreeTime39. For computational feasibility, ease of interpretation, and to balance disparate sampling efforts between countries, the Nextstrain-maintained runs sub-sample the available genomes across time and geography, resulting in final builds of ∼5,000 genomes each. After sub-sampling, the 20E (EU1) cluster within the Nextstrain build contained 5,145 sequences, 3,369 of which were unique (accounting for missing data in the sequence).

Sequences were downloaded from GISAID at the end of January and analysed using the nextstrain/ncov workflow, using a cutoff date of 30 September 2020 (for Extended Data Fig. 4a) or 30 November 2020 (for all other analyses). These dates were chosen to focus first on introductions over the summer (for 30 September) and then to highlight ongoing circulation through the autumn (30 November) before the spread of the variants of concern identified in December 2020 and January 2021. A table acknowledging the invaluable contributions by many labs is available in the Supplementary Information. The Swiss SARS-CoV-2 sequencing efforts have been described previously40,41. The majority of Swiss sequences used here are from the Nadeau et al.40 dataset and the remainder are available on GISAID.

Defining the 20E (EU1) cluster

The cluster was initially identified as a monophyletic group of sequences stemming from the larger 20A clade with amino acid substitutions at positions S:A222V, ORF10:V30L, and N:A220V or ORF14:L67F (overlapping reading frame with N), corresponding to nucleotide mutations C22227T, C28932T, and G29645T. In addition, sequences in 20E (EU1) differ from their ancestors by the synonymous mutations T445C, C6286T, and C26801G.

The sub-sampling of the standard Nextstrain analysis means that we were not able to visualize the true size or phylogenetic structure of the cluster in question. To specifically analyse this cluster using almost all available sequences, we designed a specialized build that focused on cluster-associated sequences and their most genetically similar neighbours. For computational reasons, we limited the number of samples to 900 per country per month. As only the UK has more sequences than this for the relevant time period, this results in a random downsampling of sequences from the UK for the months of August, September, and October. Furthermore, we excluded several problematic sequences because of high intra-sample variation, wrong dates, and over-divergence (divergence values were implausible given the provided dates). A full list of the sequences excluded (and the reasons why) is given on GitHub at https://github.com/neherlab/2020_EU1_paper/blob/master/scripts/bad_sequences.py.

We identified sequences in the cluster on the basis of the presence of nucleotide substitutions at positions 22227, 28932, and 29645 and used this set as a ‘focal’ sample in the nextstrain/ncov pipeline. This selection excludes any sequences with no coverage or reversions at these positions, but the similarity-based sampling during the Nextstrain run will identify these, as well as any other nearby sequences, and incorporate them into the dataset. We used these three mutations as they included the largest number of sequences that are distinct to the cluster. By this criterion, there are currently 60,316 sequences in the cluster that were sampled before 30 November 2020.

To visualize the changing prevalence of the cluster over time, we plotted the proportion of sequences identified by the four substitutions described above as a fraction of the total number of sequences submitted, per ISO week. The frequencies of other clusters were identified in an analogous way.

Phylogeny and geographic distribution

The size of the cluster and the number of unique mutations among individual sequences mean that interpreting overall patterns and connections between countries is not straightforward. We aimed to create a simplified version of the tree that focuses on connections between countries and de-emphasizes onward transmission within a country. As our focal build contained ‘background’ sequences that do not fall within the cluster, we used only the monophyletic clade containing the four amino-acid changes and three synonymous nucleotide changes that identify the cluster. Then, subtrees that contained only sequences from one country were collapsed into the parent node. The resulting phylogeny contains only mixed-country nodes and single-country nodes that have mixed-country nodes as children. (An illustrative example of this collapsing can be seen in Extended Data Fig. 4b–d.) Nodes in this tree therefore represent ancestral genotypes of subtrees: sequences represented within a node may have further diversified within their country, but share a set of common mutations. We count all sequences in the subtrees towards the geographic distribution represented in the pie charts in Extended Data Fig. 4a.

This tree allows us to infer lower bounds for the number of introductions to each country, and to identify plausible origins of those introductions. It is important to remember that, particularly for countries other than the UK, the full circulating diversity of the variant is probably not being captured, and therefore intermediate transmissions cannot be ruled out. In particular, the closest relative of a particular sequence will often have been sampled in the UK simply because sequencing efforts in the UK exceed those of most other countries by orders of magnitude. It is, however, not our goal to identify all introductions but to investigate large-scale patterns of spread in Europe.

Travel volume and destination

Mobile phone roaming data were used to estimate the number of visitors from a given country that departed from a given province for each calendar week. The mobile phone record dataset contains approximately 13 million devices, with more than 2.6 million roamers. A visitor was considered to be departing the country during a given week if they were not seen in the dataset for the next eight weeks. The nationality of a visitor was inferred from the Mobile Country Code (MCC). The total number of unique visitors was aggregated for each province and each week in the period of study; these totals were then scaled using official statistics as a reference to account for the partial coverage of the dataset.

Estimation of contributions from imports

To estimate how the frequency of 20E (EU1) is expected to change in country X as a result of travel, we considered the following simple model: A fraction αi of the population of X returns from Spain every week i (estimated from roaming data, see above) and is infected with 20E (EU1) with a probability pi given by its per capita weekly incidence in Spain. Incidence is the weighted average over incidence in Spanish provinces by the distribution of visitors across the provinces. The week-over-week fold-change of the epidemic in X is calculated as gi = (ci − αipi)/ci − 1, where ci is the per capita incidence in week i in X. This fold-change captures the local growth of the epidemic in country X. The total number of 20E (EU1) cases vi in week i is hence vi = givi – 1 + piαi, while the total number of non-20E (EU1) cases is ri = giri − 1. Running this recursion from mid-June to November results in the frequency trajectories in Fig. 3.

From 1 June 2020 to 30 September 2020, the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) reported 23,199 confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infections. Of these cases, 14,583 (62.9%) provided information about their likely place of exposure and country of infection in a clinical registration form. Of these, 3,304 (22.7%) reported exposure abroad and 136 (0.9%) named Spain as the country of infection. The Robert-Koch Institute reported statistics on likely country of infection by calendar week in their daily situation reports42.

Phylodynamic analysis of Swiss transmission chains

We identified introductions into Switzerland and downstream Swiss transmission chains by considering a tree of all available Swiss sequences combined with foreign sequences with high similarity to Swiss sequences (full procedure described previously40). Putative transmission chains were defined as majority Swiss clades allowing for at most three ‘exports’ to third countries. Identification of transmission chains is complicated by polytomies in SARS-CoV-2 phylogenies and we bounded the resulting uncertainty by either (i) considering all subtrees descending from the polytomy as separate introductions (called ‘max’ in Extended Data Fig. 8) or (ii) aggregating all into a single introduction (called ‘min’)40. We further extended this analysis to include a pan-European dataset consisting of putative transmission chains defined via the collapsed phylogenies discussed above. Specifically, each section of a pie chart, which corresponds to a country-specific collection of sequences, was taken as a single introduction. Non-20E (EU1) Re estimates were obtained from case data and the estimated frequency of 20E (EU1) in different countries.

The phylodynamic analysis of the transmission chains was performed using BEAST2 with a birth–death-model tree prior43,44. 20E (EU1) and non-20E (EU1) variants share a sampling probability and logRe has an Ornstein–Uhlenbeck prior as described in ref. 40 (but note a different smoothing prior was used there).

ELISA

We coated 384-well Maxisorp plates (Thermo Fisher) overnight at room temperature with 3 μg/ml of SARS-CoV-2 S2P45 or SARS-CoV-2 A222V D614G S2P in 20 mM Tris pH 8 and 150 mM NaCl, produced as previously described21. In brief, Expi293F cells were transiently transcribed with a plasmid containing the spike protein and supernatant was clarified six days later before Ni Sepharose resin purification and flash freezing. Gibco (Fisher) Expi293F cells were used for protein production and have not been authenticated or tested for mycoplasma contamination. They are not in the database of commonly misidentified cell lines. Plates were slapped dry and blocked with Blocker Casein in TBS (Thermo Fisher) for 1 h at 37 °C. Plates were slapped dry and 1 μM S2E1218, S30922, or 4A824 IgG or 1:4 NIBSC human plasma (20/130; https://www.nibsc.org/documents/ifu/20-130.pdf) was serially diluted 1:3 in TBST and incubated for one hour at 37 °C. Plates were washed 4× with TBST using a 405 TS Microplate Washer (BioTek) followed by addition of 1:5,000 goat anti-human Fc IgG-HRP (Thermo Fisher) for one hour at 37 °C. Plates were washed 4× and TMB Microwell Peroxidase (Seracare) was added. The reaction was quenched after 1–2 min with 1 N HCl and the A450 of each well was read using a Varioskan Lux plate reader (Thermo Fisher).

Pseudotyped lentivirus production and titres

The S:A222V mutation was introduced into the protein-expression plasmid HDM-Spiked21-D614G, which encodes a codon-optimized spike from Wuhan-Hu-1 (GenBank NC 045512) with a 21-amino acid cytoplasmic tail deletion and the D614G mutation46. This plasmid is also available on AddGene (plasmid 158762). We made two different versions of the A222V mutant that differed only in which codon was used to introduce the valine mutation (either GTT or GTC). The sequences of these plasmids (HDM Spike-d21D614G-A222V-GTT and HDM Spike-d21-D614G-A222V-GTC) are available as supplement files at https://github.com/neherlab/2020_EU1_paper/tree/master/plasmid_data.

Spike-pseudotyped lentiviruses were produced as described46. Two separate plasmid preps of the A222V (GTT) spike and one plasmid prep of the A222V (GTC) spike were each used in duplicate to produce six replicates of A222V spike-pseudotyped lentiviruses. Three plasmid preps of the initial D614G spike plasmid (with the 21-amino acid cytoplasmic tail truncation) were each used once used to make three replicates of D614G spike-pseudotyped lentiviruses. All viruses were titred in duplicate.

Lentiviruses were produced with both Luciferase IRES ZsGreen and ZsGreen-only lentiviral backbones46, and then titred using luciferase signal or percentage of fluorescent cells, respectively. All viruses were titred in 293T-ACE2 cells (BEI NR-52511) as described47, with the following modifications. Viruses containing luciferase were titred starting at a 1:10 dilution followed by five serial twofold dilutions. The Promega BrightGlo luciferase system was used to measure relative luciferase units (RLUs) ∼65 h post-infection and RLUs per ml were calculated at each dilution then averaged across all dilutions for each virus. Viruses containing only ZsGreen were titred starting at a 1:3 dilution followed by four serial fivefold dilutions. The 1:375 dilution was visually determined to be ∼1% positive about 65 h post-infection and was used to calculate the percent of infected cells using flow cytometry (BD FACSCelesta cell analyser). Viral titres were then calculated using the percentage of green cells via the Poisson formula. To normalize viral titres by lentiviral particle production, p24 concentration (in pg/ml) was quantified by ELISA according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Advanced Bioscience Laboratories Cat. 5421). All viral supernatants were measured in technical duplicates at a 1:100,000 dilution.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this paper.

Data availability

Sequence data were obtained from GISAID and tables listing all accession numbers of sequences are available in the Supplementary Information.

Code availability

Code used for the above analyses is available on GitHub at https://github.com/neherlab/2020_EU1_paper. The code used to run the cluster builds is available on GitHub at https://github.com/emmahodcroft/ncov_cluster.

References

WHO Emergency Committee. Statement on the Second Meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee Regarding the Outbreak of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) https://www.who.int/news/item/30-01-2020-statement-on-the-second-meeting-of-the-international-health-regulations-(2005)-emergency-committee-regarding-the-outbreak-of-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov) (2020).

Zhu, N. et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 727–733 (2020).

Worobey, M. et al. The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 in Europe and North America. Science 370, 564–570 (2020).

Hadfield, J. et al. Nextstrain: real-time tracking of pathogen evolution. Bioinformatics 34, 4121–4123 (2018).

du Plessis, L. et al. Establishment and lineage dynamics of the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in the UK. Science 371, 708–712 (2021).

Shu, Y. & McCauley, J. GISAID: global initiative on sharing all influenza data — from vision to reality. Euro Surveill. 22, 30494 (2017).

Korber, B. et al. Tracking changes in SARS-CoV-2 spike: evidence that D614G increases infectivity of the COVID-19 virus. Cell 182, 812–827.e19 (2020).

Volz, E. et al. Evaluating the effects of SARS-CoV-2 spike mutation D614G on transmissibility and pathogenicity. Cell 184, 64–75.e11 (2020).

Plante, J. A. et al. Spike mutation D614G alters SARS-CoV-2 fitness. Nature 592, 116–121 (2021).

Yurkovetskiy, L. et al. Structural and functional analysis of the D614G SARS-CoV-2 spike protein variant. Cell 183, 739–751.e8 (2020).

Davies, N. G. et al. Estimated transmissibility and impact of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 in England. Science 372, eabg3055 (2021).

Volz, E. et al. Assessing transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 in England. Nature 593, 266–269 (2021).

Pearson, C. A. B. et al. Estimates of severity and transmissibility of novel SARS-CoV-2 variant 501Y.V2 in South Africa. Preprint at https://cmmid.github.io/topics/covid19/sa-novel-variant.html (2021).

Tegally, H. et al. Detection of a SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern in South Africa. Nature 592, 438–443 (2021).

Sabino, E. C. et al. Resurgence of COVID-19 in Manaus, Brazil, despite high seroprevalence. Lancet 397, 452–455 (2021).

Rambaut, A. et al. A dynamic nomenclature proposal for SARS-CoV-2 lineages to assist genomic epidemiology. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 1403–1407 (2020).

Barnes, C. O. et al. SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody structures inform therapeutic strategies. Nature 588, 682–687 (2020).

Tortorici, M. A. et al. Ultrapotent human antibodies protect against SARS-CoV-2 challenge via multiple mechanisms. Science 370, 950–957 (2020).

Thomson, E. C. et al. Circulating SARS-CoV-2 spike N439K variants maintain fitness while evading antibody-mediated immunity. Cell 184, 1171–1187 (2021).

McCallum, M., Walls, A. C., Bowen, J. E., Corti, D. & Veesler, D. Structure-guided covalent stabilization of coronavirus spike glycoprotein trimers in the closed conformation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 27, 942–949 (2020).

Walls, A. C. et al. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Cell 181, 281–292.e6 (2020).

Pinto, D. et al. Cross-neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 by a human monoclonal SARS-CoV antibody. Nature 583, 290–295 (2020).

Walls, A. C. et al. Elicitation of potent neutralizing antibody responses by designed protein nanoparticle vaccines for SARS-CoV-2. Cell 183, 1367–1382.e17 (2020).

Chi, X. et al. A neutralizing human antibody binds to the N-terminal domain of the Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2. Science 369, 650–655 (2020).

McCallum, M. et al. N-terminal domain antigenic mapping reveals a site of vulnerability for SARS-CoV-2. Cell 184, 2332–2347.e16 (2021).

Finkel, Y. et al. The coding capacity of SARS-CoV-2. Nature 589, 125–130 (2021).

Pancer, K. et al. The SARS-CoV-2 ORF10 is not essential in vitro or in vivo in humans. PLoS Pathog. 16, e1008959 (2020).

Grubaugh, N. D., Hanage, W. P. & Rasmussen, A. L. Making sense of mutation: what D614G means for the COVID-19 pandemic remains unclear. Cell 182, 794–795 (2020).

Instituto Nacional de Estadistica. Hotel Industry and Tourism – Tourist Movement on Borders Survey Frontur. (accessed December 2020); https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/en/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176996&menu=resultados&secc=1254736195568&idp=1254735576863

Aena.es. Air Traffic Statistics (accessed January 2021); https://portal.aena.es/en/corporate/air-traffic-statistics.html

Correa-Martínez, C. L. et al. A pandemic in times of global tourism: superspreading and exportation of COVID-19 cases from a ski area in austria. J. Clin. Microbiol. 58, e00588-20 (2020).

Knabl, L. et al. High SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence in children and adults in the Austrian ski resort Ischgl. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.20.20178533 (2020).

Mossong, J. et al. Social contacts and mixing patterns relevant to the spread of infectious diseases. PLoS Med. 5, e74 (2008).

Jarvis, C. I. et al. Quantifying the impact of physical distance measures on the transmission of COVID-19 in the UK. BMC Med. 18, 124 (2020).

Neher, R. A., Dyrdak, R., Druelle, V., Hodcroft, E. B. & Albert, J. Potential impact of seasonal forcing on a SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Swiss Med. Wkly. 150, w20224 (2020).

Lauring, A. S. & Hodcroft, E. B. Genetic variants of SARS-CoV-2—what do they mean? J. Am. Med. Assoc. 325, 529–531 (2021).

Katoh, K., Misawa, K., Kuma, K. & Miyata, T. MAFFT: a novel method for rapid multiple sequence alignment based on fast Fourier transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 3059–3066 (2002).

Minh, B. Q. et al. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37, 1530–1534 (2020).

Sagulenko, P., Puller, V. & Neher, R. A. TreeTime: maximum-likelihood phylodynamic analysis. Virus Evol. 4, vex042 (2018).

Nadeau, S. et al. Quantifying SARS-CoV-2 spread in Switzerland based on genomic sequencing data. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.14.20212621 (2020).

Stange, M. et al. SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in a tri-national urban area is dominated by a B.1 lineage variant linked to mass gathering events. PLOS Pathog. 17, e1009374 (2021).

Robert Koch Institute. Aktueller Lage-/Situationsbericht des RKI zu COVID-19 https://www.rki.de/DE/Content/InfAZ/N/Neuartiges_Coronavirus/Situationsberichte/Gesamt.html (2020).

Stadler, T., Kühnert, D., Bonhoeffer, S. & Drummond, A. J. Birth-death skyline plot reveals temporal changes of epidemic spread in HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 228–233 (2013).

Bouckaert, R. et al. BEAST 2.5: an advanced software platform for Bayesian evolutionary analysis. PLOS Comput. Biol. 15, e1006650 (2019).

Pallesen, J. et al. Immunogenicity and structures of a rationally designed prefusion MERS-CoV spike antigen. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, E7348–E7357 (2017).

Greaney, A. J. et al. Complete mapping of mutations to the SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor-binding domain that escape antibody recognition. Cell Host Microbe 29, 44–57.e9 (2021).

Crawford, K. H. D. et al. Protocol and reagents for pseudotyping lentiviral particles with SARS-CoV-2 spike protein for neutralization assays. Viruses 12, 513 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank researchers, clinicians, and public health authorities for making SARS-CoV-2 sequence data available in a timely manner; the COVID-19 Genomics UK consortium for their sequencing efforts, which have provided a third of the sequences currently publicly available; and the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) for providing access to their data. This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) through grant numbers 31CA30 196046 (to R.A.N., E.B.H., and C.L.A.) and 31CA30 196267 (to T.S.), the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme project EpiPose (no 101003688) (to M.L.R. and C.L.A.), core funding by the University of Basel and ETH Zürich, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (R01GM120553 to D.V.), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (DP1AI158186 and HHSN272201700059C to D.V.), a Pew Biomedical Scholars Award (to D.V.), an Investigators in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease Awards from the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (to D.V. and J.D.B.), a Fast Grants award (to D.V.), and NIAID grants R01AI141707 (to J.D.B.) and F30AI149928 (to K.H.D.C.). SeqCOVID-SPAIN is funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III project COV20/00140, Spanish National Research Council and ERC StG 638553 to I.C. and BFU2017-89594R from MICIN to F.G.C. J.D.B. is an Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

E.B.H. identified the cluster, led the analysis, created figures, and drafted the manuscript. R.A.N. analysed data, created figures, and drafted the manuscript. M.Z., S.N., T.G.V., C.L.A., T.S., and M.L.R. analysed data and created figures. D.V. investigated structural aspects and created figures. J.D.B., J.E.B., A.C.W., D.C., and K.H.D.C. performed experimental assays and created figures. I.C. and F.G.C. interpreted the origins of the cluster and contributed data. D.M. and A.H. contributed and interpreted data. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

D.V. is a consultant for Vir Biotechnology. D.C. is an employee of Vir Biotechnology and may hold shares in Vir Biotechnology. The Veesler laboratory has received an unrelated sponsored research agreement from Vir Biotechnology. A.H. is a co-founder of Kido Dynamics and D.M. is employed by Kido Dynamics. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

Extended Data Fig. 1 Variant dynamics in different European countries.

In countries with at least ten sequences that fall into any of the defined clusters, the proportion of sequences per ISO week that fall into each cluster is shown.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Structure model of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein.

Two orthogonal orientations of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein trimer highlighting the position of the variants described in the manuscript and the RBD and NTD (domain A).

Extended Data Fig. 3 The substitution A222V in the spike protein has no substantial effect on antigenic properties or replication of pseudotyped lentiviruses.

a, Binding of a serial dilution of NIBSC convalescent plasma to immobilized SARSCoV-2 2P S (blue) or SARS-CoV-2 2P A222V D614G S (red). b, c, Binding of serially diluted concentrations of the human neutralizing antibodies S2E12 (b) and S309 (c) to immobilized SARSCoV-2 2P S (blue) or SARS-CoV-2 2P A222V D614G S (red). d, Binding of serially diluted concentrations of the human neutralizing antibody 4A8 to immobilized SARS-CoV-2 2P S (blue) or SARS-CoV-2 2P A222V D614G S (red). n = 2 experiments performed with independent protein preparations (each in duplicate). Each data point consists of a technical duplicate of each antibody or plasma dilution; error bars, s.d. The experiment shown is representative of two independent experiments. e, Titres of lentiviral particles carrying luciferase in the viral genome. Horizontal line, mean. f, Titres of lentiviral particles carrying the fluorescent protein ZsGreen in the viral genome. Horizontal line, mean. In e, f, titres with the A222V mutation are on average higher by a factor of 1.3. g, Titres of lentiviral particles carrying luciferase in the viral genome normalized by the p24 concentration (pg ml−1) of each viral supernatant. After p24 normalization, the difference in titre shrinks from 1.28- to 1.14-fold, increasing the P value to 0.16. h, Titres of lentiviral particles carrying ZsGreen in the viral genome normalized by the p24 concentration (pg ml−1) of each viral supernatant. P values calculated using two-sided t-test.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Collapsed genotype phylogeny and statistics of putative introductions.

a, The phylogeny shown is the subtree of the 20E (EU1) cluster using data from samples collected before 30 September 2020 and available on GISAID as of January 2021, with sequences carrying all six defining mutations. Pie charts show the representation of sequences from selected countries at each node. The size of each pie chart indicates the total number of sequences at each node. Pie chart fractions scale nonlinearly with the true counts (fourth root) to ensure that all countries are visible and branch lengths are jittered to reduce overlap. Although the jitter means that branch lengths should be interpreted with caution, the smallest branches shown in the tree are equal to one mutation. b–d, An example of how the pie chart phylogeny was created. The tree is shown in ‘divergence view’ with the branch lengths in mutations. Internal nodes are shown as horizontal lines with other nodes (internal and external) branching from them. If sequences are identical, they align on the horizontal line. In this example zooming in to the Norwegian cluster, the outermost tips are first collapsed down to their parental node (b), forming a pie chart that consists only of sequences from Denmark (c). This single-country pie chart is collapsed with the next level of nodes (d), including more sequences from Denmark and sequences from Norway, to form a multi-country pie chart. e, Rank-order plots of sizes of clusters of sequences in the pie chart slices, in different countries, compatible with a single introduction. Countries such as Norway and Iceland have relatively few clusters, with one or two large clusters dominating, which suggests that a small number of introductions dominated 20E (EU1) circulation. Countries such as the UK and Denmark, on the other hand, show many clusters of varying size, indicating that multiple introductions led to onward spread. The legend indicates total number of sequences s and number of clusters c.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Incidence in various countries over the summer.

a, Spain and Belgium had relatively higher incidence from the start of July compared with other countries in Europe. b, The estimated total number of EU1 infections (red) outside Spain (countries as in a) surpassed the number in Spain in September.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Rescaled predictions by the import model match observed frequency trajectories.

In most countries, observations of 20E (EU1) increased in July 2020 and reached a plateau or a slower increase by October 2020. Predictions by the import model need to be scaled by a factor between 1.2 and 12 (see legends in individual plots) to match the observed frequencies (see main text for discussion). Fluctuations on short time scales in the observed frequency of 20E (EU1) are probably due to sampling and the dynamics of local outbreaks. Observed frequencies are subject to variable reporting delays.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Reported and estimated introductions of 20E (EU1) to Germany and Switzerland and incidence in Spain by province and similarity in Spanish province travel destination of selected European countries.

a, Germany; b, Switzerland. Travel estimate is estimated introductions from Spain based on incidence and roaming data. Reported cases are cases with a suspected origin in Spain as reported by the RKI (Robert Koch Institute, 2020) and the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) for Germany and Switzerland, respectively. In Switzerland the adjusted rep. cases accounts for the fact that 37% of case reports lack exposure information. c, Incidence in Spain in early and mid-summer. d, Distributions of visitors to Spain from different countries. e, Similarities of destinations in Spain among visitors from different countries in calendar weeks 28–35.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Phylodynamic analysis of the spread of the 20E (EU1) variant across Europe and in Switzerland.

a, d, Across Europe; b, c, e, f, in Switzerland. a–c, The sizes of putative transmission chains caused by introductions into Europe and Switzerland. Not shown are the number of singletons, which are introductions with no evidence of onward transmission. In Switzerland, these are shown under two extreme definitions of an introduction (min and max; see Methods). Depending on the min or max definition of introductions, there were between 14 and 236 singletons of 20E (EU1) infection (41% or 81% of all 20E (EU1) introductions) and between 62 and 1,089 singletons of other variants (30% or 79% of all non-20E (EU1) introductions). In Europe, we see 206 20E (EU1) singletons (46% of all 20E (EU1) introductions). There were also a small number of larger transmission chains that included more than 53 transmissions (20 across all datasets), which are not shown in the histograms. d–f, The effective reproductive number estimated for 20E (EU1) (red) and the non-20E (EU1) variants (blue). In Switzerland, this was done for the two extreme definitions of an introduction. For Europe, non-20E (EU1) Re estimates were generated from case numbers. Although there are few data to inform estimates of Re for 20E (EU1) in July and it differs little from the prior, there is some evidence that 20E (EU1) was growing faster than other variants in August. However, systematic differences in ascertainment in travel associated cases might confound this inference. From mid-September, Re of 20E (EU1) is largely statistically indistinguishable from that of other variants. Shaded areas indicate 95% highest posterior density regions. Notably, the peak in August in the Swiss analysis is larger under the ‘min’ definition (f) than under the ‘max’ definition (e), consistent with a more conservative definition of a cluster which would then require more onward transmission. See Extended Data Fig. 9 for details on all variants circulating in Switzerland May–October 2020.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Lineages found in a Swiss-focused Nextstrain build.

A lineage is defined as a node present in the tree after the cut-off date of 1 May 2020 with at least ten Swiss sequences as children. Clusters discussed in this manuscript are labelled. Lineages are shown as the proportion of the total number of sequences per week in Switzerland. Striped space in the bottom graph represents lineages with most recent common ancestors dating back before 1 May 2020 and lineages that do not contain at least ten Swiss sequences.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains additional information about the first sequences identified for selected countries across Europe, as well as information about travel restrictions and quarantine requirements over the summer of 2020. It also includes Supplementary Tables 1-2.

Supplementary Information

This file contains contains the attributions for the data providers and submitters for the sequences used in this analysis.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hodcroft, E.B., Zuber, M., Nadeau, S. et al. Spread of a SARS-CoV-2 variant through Europe in the summer of 2020. Nature 595, 707–712 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03677-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03677-y

This article is cited by

-

Drivers and impact of the early silent invasion of SARS-CoV-2 Alpha

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Dispersion patterns of SARS-CoV-2 variants Gamma, Lambda and Mu in Latin America and the Caribbean

Nature Communications (2024)

-

COVID-19 epidemic peaks distribution in the United-States of America, from epidemiological modeling to public health policies

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Fitness, growth and transmissibility of SARS-CoV-2 genetic variants

Nature Reviews Genetics (2023)

-

Maximum likelihood pandemic-scale phylogenetics

Nature Genetics (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.