Abstract

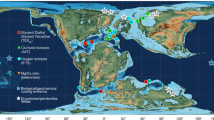

The magnitude of global cooling during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, the coldest multimillennial interval of the last glacial period) is an important constraint for evaluating estimates of Earth’s climate sensitivity1,2. Reliable LGM temperatures come from high-latitude ice cores3,4, but substantial disagreement exists between proxy records in the low latitudes1,5,6,7,8, where quantitative low-elevation records on land are scarce. Filling this data gap, noble gases in ancient groundwater record past land surface temperatures through a direct physical relationship that is rooted in their temperature-dependent solubility in water9,10. Dissolved noble gases are suitable tracers of LGM temperature because of their complete insensitivity to biological and chemical processes and the ubiquity of LGM-aged groundwater around the globe11,12. However, although several individual noble gas studies have found substantial tropical LGM cooling13,14,15,16, they have used different methodologies and provide limited spatial coverage. Here we use noble gases in groundwater to show that the low-altitude, low-to-mid-latitude land surface (45 degrees south to 35 degrees north) cooled by 5.8 ± 0.6 degrees Celsius (mean ± 95% confidence interval) during the LGM. Our analysis includes four decades of groundwater noble gas data from six continents, along with new records from the tropics, all of which were interpreted using the same physical framework. Our land-based result broadly supports a recent reconstruction based on marine proxy data assimilation1 that suggested greater climate sensitivity than previous estimates5,6,7.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All original groundwater data (noble gas concentrations, ages, water temperatures (if available)), recharge elevations, study locations, fitted parameters and statistical uncertainties are freely available for download through PANGAEA (https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.929176). NGT time series plots of each study are available as supplementary files. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All MATLAB scripts for NGT fitting (including documentation) are freely available from zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4589442).

References

Tierney, J. E. et al. Glacial cooling and climate sensitivity revisited. Nature 584, 569–573 (2020).

Schmittner, A. et al. Climate sensitivity estimated from temperature reconstructions of the Last Glacial Maximum. Science 334, 1385–1388 (2011).

Jouzel, J. et al. Orbital and millennial Antarctic climate variability over the past 800,000 years. Science 317, 793–796 (2007).

Petit, J. R. et al. Climate and atmospheric history of the past 420,000 years from the Vostok ice core, Antarctica. Nature 399, 429–436 (1999).

CLIMAP Project Members. The surface of the Ice-Age Earth. Science 191, 1131–1137 (1976).

MARGO Project Members. Constraints on the magnitude and patterns of ocean cooling at the Last Glacial Maximum. Nat. Geosci. 2, 127–132 (2009).

Annan, J. D. & Hargreaves, J. C. A new global reconstruction of temperature changes at the Last Glacial Maximum. Clim. Past 9, 367–376 (2013).

Farrera, I. et al. Tropical climates at the Last Glacial Maximum: a new synthesis of terrestrial palaeoclimate data. I. Vegetation, lake-levels and geochemistry. Clim. Dyn. 15, 823–856 (1999).

Jenkins, W. J., Lott, D. E. & Cahill, K. L. A determination of atmospheric helium, neon, argon, krypton, and xenon solubility concentrations in water and seawater. Mar. Chem. 211, 94–107 (2019).

Kipfer, R., Aeschbach-Hertig, W., Peeters, F. & Stute, M. Noble gases in lakes and ground waters. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 47, 615–700 (2002).

Befus, K. M., Jasechko, S., Luijendijk, E., Gleeson, T. & Bayani Cardenas, M. The rapid yet uneven turnover of Earth’s groundwater. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 5511–5520 (2017).

Jasechko, S. et al. Global aquifers dominated by fossil groundwaters but wells vulnerable to modern contamination. Nat. Geosci. 10, 425–429 (2017).

Stute, M. et al. Cooling of tropical Brazil (5 °C) during the Last Glacial Maximum. Science 269, 379–383 (1995).

Weyhenmeyer, C. E. et al. Cool glacial temperatures and changes in moisture source recorded in Oman groundwaters. Science 287, 842–845 (2000).

Stute, M., Schlosser, P., Clark, J. F. & Broecker, W. S. Paleotemperatures in the southwestern United States derived from noble gases in ground water. Science 256, 1000–1003 (1992).

Kulongoski, J. T., Hilton, D. R. & Selaolo, E. T. Climate variability in the Botswana Kalahari from the late Pleistocene to the present day. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, L10204 (2004).

Porter, S. C. Snowline depression in the tropics during the last glaciation. Quat. Sci. Rev. 20, 1067–1091 (2000).

Rind, D. & Peteet, D. Terrestrial conditions at the Last Glacial Maximum and CLIMAP sea-surface temperature estimates: are they consistent? Quat. Res. 24, 1–22 (1985).

Klein, A. G., Seltzer, G. O. & Isacks, B. L. Modern and last local glacial maximum snowlines in the Central Andes of Peru, Bolivia, and Northern Chile. Quat. Sci. Rev. 18, 63–84 (1999).

Tierney, J. E. et al. Northern Hemisphere controls on tropical southeast African climate during the past 60,000 years. Science 322, 252–255 (2008).

Powers, L. A. et al. Large temperature variability in the southern African tropics since the Last Glacial Maximum. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L08706 (2005).

Loomis, S. E. et al. The tropical lapse rate steepened during the Last Glacial Maximum. Sci. Adv. 3, e1600815 (2017).

Bartlein, P. J. et al. Pollen-based continental climate reconstructions at 6 and 21 ka: a global synthesis. Clim. Dyn. 37, 775–802 (2011).

Mazor, E. Paleotemperatures and other hydrological parameters deduced from noble gases dissolved in groundwaters; Jordan Rift Valley, Israel. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 36, 1321–1336 (1972).

Stute, M. & Schlosser, P. in Climate Change in Continental Isotopic Records Vol. 78 (eds Swart, P. K. et al.) 89–100 (American Geophysical Union (AGU), 1993).

Aeschbach-Hertig, W. & Solomon, D. K. in The Noble Gases as Geochemical Tracers (ed. Burnard, P.) 81–122 (Springer, 2013).

Pepin, R. O. & Porcelli, D. Origin of noble gases in the terrestrial planets. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 47, 191–246 (2002).

Klump, S., Cirpka, O. A., Surbeck, H. & Kipfer, R. Experimental and numerical studies on excess-air formation in quasi-saturated porous media. Wat. Resour. Res. 44, W05402 (2008).

Klump, S. et al. Field experiments yield new insights into gas exchange and excess air formation in natural porous media. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 71, 1385–1397 (2007).

Aeschbach-Hertig, W., El-Gamal, H., Wieser, M. & Palcsu, L. Modeling excess air and degassing in groundwater by equilibrium partitioning with a gas phase. Wat. Resour. Res. 44, W08449 (2008).

Aeschbach-Hertig, W., Peeters, F., Beyerle, U. & Kipfer, R. Palaeotemperature reconstruction from noble gases in ground water taking into account equilibration with entrapped air. Nature 405, 1040–1044 (2000).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Hall, C. M., Castro, M. C., Lohmann, K. C. & Ma, L. Noble gases and stable isotopes in a shallow aquifer in southern Michigan: implications for noble gas paleotemperature reconstructions for cool climates. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, L18404 (2005).

Chang, J. Ground Temperature (Blue Hill Meteorological Observatory, Harvard University, 1958).

Hall, C. M., Castro, M. C., Lohmann, K. C. & Sun, T. Testing the noble gas paleothermometer with a yearlong study of groundwater noble gases in an instrumented monitoring well. Wat. Resour. Res. 48, W04517 (2012).

Han, L. F. & Plummer, L. N. A review of single-sample-based models and other approaches for radiocarbon dating of dissolved inorganic carbon in groundwater. Earth Sci. Rev. 152, 119–142 (2016).

Aeschbach-Hertig, W., Stute, M., Clark, J. F., Reuter, R. F. & Schlosser, P. A paleotemperature record derived from dissolved noble gases in groundwater of the Aquia Aquifer (Maryland, USA). Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 66, 797–817 (2002).

Jung, M., Wieser, M., von Oehsen, A. & Aeschbach-Hertig, W. Properties of the closed-system equilibration model for dissolved noble gases in groundwater. Chem. Geol. 339, 291–300 (2013).

Prentice, I. C., Harrison, S. P. & Bartlein, P. J. Global vegetation and terrestrial carbon cycle changes after the last ice age. New Phytol. 189, 988–998 (2011).

Stute, M. & Sonntag, C. in Isotopes of Noble Gases as Tracers in Environmental Studies 111–122 (International Atomic Energy Agency, 1992).

Seltzer, A. M. et al. Deglacial water-table decline in Southern California recorded by noble gas isotopes. Nat. Commun. 10, 5739 (2019).

Seltzer, A. M., Severinghaus, J. P., Andraski, B. J. & Stonestrom, D. A. Steady state fractionation of heavy noble gas isotopes in a deep unsaturated zone. Wat. Resour. Res. 53, 2716–2732 (2017).

Mélières, M. A., Martinerie, P., Raynaud, D. & Lliboutry, L. Glacial–interglacial mean sea level pressure change due to sea level, ice sheet and atmospheric mass changes. Global Planet. Change 3, 333–340 (1991).

Cey, B. D. On the accuracy of noble gas recharge temperatures as a paleoclimate proxy. J. Geophys. Res. 114, D04107 (2009).

Broecker, W. S. & Denton, G. H. The role of ocean–atmosphere reorganizations in glacial cycles. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 53, 2465–2501 (1989).

Manabe, S., Stouffer, R. J., Spelman, M. J. & Bryan, K. Transient responses of a coupled ocean–atmosphere model to gradual changes of atmospheric CO2. Part I. annual mean response. J. Clim. 4, 785–818 (1991).

Joshi, M. M., Gregory, J. M., Webb, M. J., Sexton, D. M. H. & Johns, T. C. Mechanisms for the land/sea warming contrast exhibited by simulations of climate change. Clim. Dyn. 30, 455–465 (2008).

Sutton, R. T., Dong, B. & Gregory, J. M. Land/sea warming ratio in response to climate change: IPCC AR4 model results and comparison with observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L02701 (2007).

Knutti, R. & Hegerl, G. C. The equilibrium sensitivity of the Earth’s temperature to radiation changes. Nat. Geosci. 1, 735–743 (2008).

Steiger, N. J., Hakim, G. J., Steig, E. J., Battisti, D. S. & Roe, G. H. Assimilation of time-averaged pseudoproxies for climate reconstruction. J. Clim. 27, 426–441 (2014).

Ghadiri, E. et al. Noble gas based temperature reconstruction on a Swiss stalagmite from the last glacial–interglacial transition and its comparison with other climate records. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 495, 192–201 (2018).

Heaton, T. H. E., Talma, A. S. & Vogel, J. C. Dissolved gas paleotemperatures and 18O variations derived from groundwater near Uitenhage, South Africa. Quat. Res. 25, 79–88 (1986).

Freundt, F., Schneider, T. & Aeschbach-Hertig, W. Response of noble gas partial pressures in soil air to oxygen depletion. Chem. Geol. 339, 283–290 (2013).

Castro, M. C., Hall, C. M., Patriarche, D., Goblet, P. & Ellis, B. R. A new noble gas paleoclimate record in Texas—basic assumptions revisited. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 257, 170–187 (2007).

Ma, L., Castro, M. C. & Hall, C. M. A late Pleistocene–Holocene noble gas paleotemperature record in southern Michigan. Geophys. Res. Lett. 31, L23204 (2004).

Masbruch, M. D., Chapman, D. S. & Solomon, D. K. Air, ground, and groundwater recharge temperatures in an alpine setting, Brighton Basin, Utah. Wat. Resour. Res. 48, W10530 (2012).

Saraceno, J., Kulongoski, J. T. & Mathany, T. M. A novel high-frequency groundwater quality monitoring system. Environ. Monit. Assess. 190, 477 (2018).

Jung, M. & Aeschbach, W. A new software tool for the analysis of noble gas data sets from (ground)water. Environ. Model. Softw. 103, 120–130 (2018).

Clark, J. F., Stute, M., Schlosser, P., Drenkard, S. & Bonani, G. A tracer study of the Floridan Aquifer in southeastern Georgia: implications for groundwater flow and paleoclimate. Wat. Resour. Res. 33, 281–289 (1997).

Stuiver, M. & Polach, H. A. Reporting of 14C data. Radiocarbon 19, 355–363 (1977).

Bereiter, B., Shackleton, S., Baggenstos, D., Kawamura, K. & Severinghaus, J. Mean global ocean temperatures during the last glacial transition. Nature 553, 39–44 (2018).

Schwander, J. in The Environmental Record in Glaciers and Ice Sheets (eds Oeschger, H. & Langway, C. C.) 53–67 (Wiley, 1989).

Andrews, J. N. & Lee, D. J. Inert gases in groundwater from the Bunter Sandstone of England as indicators of age and palaeoclimatic trends. J. Hydrol. 41, 233–252 (1979).

Stute, M., Clark, J. F., Schlosser, P., Broecker, W. S. & Bonani, G. A. 30,000 yr Continental paleotemperature record derived from noble gases dissolved in groundwater from the San Juan Basin, New Mexico. Quat. Res. 43, 209–220 (1995).

Beyerle, U. et al. Climate and groundwater recharge during the last glaciation in an ice-covered region. Science 282, 731–734 (1998).

Clark, J. F., Davisson, M. L., Hudson, G. B. & MacFarlane, P. A. Noble gases, stable isotopes, and radiocarbon as tracers of flow in the Dakota aquifer, Colorado and Kansas. J. Hydrol. 211, 151–167 (1998).

Kulongoski, J. T., Hilton, D. R., Izbicki, J. A. & Belitz, K. Evidence for prolonged El Niño-like conditions in the Pacific during the Late Pleistocene: a 43 ka noble gas record from California groundwaters. Quat. Sci. Rev. 28, 2465–2473 (2009).

Seltzer, A. M., Stute, M., Morgenstern, U., Stewart, M. K. & Schaefer, J. M. Mean annual temperature in New Zealand during the last glacial maximum derived from dissolved noble gases in groundwater. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 431, 206–216 (2015).

Zhu, C. & Kipfer, R. Noble gas signatures of high recharge pulses and migrating jet stream in the late Pleistocene over Black Mesa, Arizona, United States. Geology 38, 83–86 (2010).

Edmunds, W. M., Ma, J., Aeschbach-Hertig, W., Kipfer, R. & Darbyshire, D. P. F. Groundwater recharge history and hydrogeochemical evolution in the Minqin Basin, North West China. Appl. Geochem. 21, 2148–2170 (2006).

Kreuzer, A. M. et al. A record of temperature and monsoon intensity over the past 40 kyr from groundwater in the North China Plain. Chem. Geol. 259, 168–180 (2009).

Stute, M. & Deak, J. Environmental isotope study (14C, 13C, 18O, D, noble gases) on deep groundwater circulation systems in Hungary with reference to paleoclimate. Radiocarbon 31, 902–918 (1989).

Beyerle, U. et al. Evidence for periods of wetter and cooler climate in the Sahel between 6 and 40 kyr BP derived from groundwater. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30, 1173 (2003).

Varsányi, I., Palcsu, L. & Kovács, L. Ó. Groundwater flow system as an archive of palaeotemperature: noble gas, radiocarbon, stable isotope and geochemical study in the Pannonian Basin, Hungary. Appl. Geochem. 26, 91–104 (2011).

Corcho Alvarado, J. A. et al. European climate variations over the past half-millennium reconstructed from groundwater. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L15703 (2009).

Blaser, P. C. et al. A 40 ka record of temperature and permafrost conditions in northwestern Europe from noble gases in the Ledo-Paniselian Aquifer (Belgium). J. Quat. Sci. 25, 1038–1044 (2010).

Klump, S., Grundl, T., Purtschert, R. & Kipfer, R. Groundwater and climate dynamics derived from noble gas, 14C, and stable isotope data. Geology 36, 395–398 (2008).

Stute, M. & Talma, A. Glacial temperatures and moisture transport regimes reconstructed from noble gases and δ18O, Stampriet aquifer, Namibia. In Isotope Techniques in the Study of Past and Current Environmental Changes in the Hydrosphere and the Atmosphere 307–328 (1998).

Carreira, P. M. Paleoáguas de Aveiro (Universidade de Aviero, 1998).

Sundal, A., Brennwald, M. S., Aagaard, P. & Kipfer, R. Noble gas composition and 3H/3He groundwater ages in the Gardermoen Aquifer, Norway: improved understanding of flow dynamics as a tool for water management. Sci. Total Environ. 660, 1219–1231 (2019).

Trabelsi, R., Matsumoto, T., Zouari, K., Trabelsi, M. & Kumar, B. Investigation of paleoclimate signatures in Sfax deep groundwater (Southeastern Tunisia) using environmental isotopes and noble gases. Quat. Int. 547, 208–219 (2020).

Abouelmagd, A. et al. Paleoclimate record in the Nubian Sandstone Aquifer, Sinai Peninsula, Egypt. Quat. Res. 81, 158–167 (2014).

Wieser, M. Imprints of Climatic and Environmental Change in a Regional Aquifer System in an Arid Part of India using Noble Gases and Other Environmental Tracers (University of Heidelberg, 2011).

Wieser, M., Aeschbach-Hertig, W., Schneider, T., Deshpande, R. D. & Gupta, S. K. A temperature and monsoon record derived from environmental tracers in the groundwater of northwest India. In International Symposium on Isotopes in Hydrology, Marine Ecosystems and Climate Change Studies 7–14 (International Atomic Energy Agency, 2013).

Acknowledgements

We thank the entire community of groundwater noble gas geochemists, particularly the pioneers E. Mazor and J. N. Andrews, for decades of careful work in analysing groundwater from around the world and furthering our physical understanding of inert gases in groundwater; A. Moulla and T. Condesso de Melo for sharing data, and D. Bekaert for helpful discussions. The manuscript was improved by helpful suggestions from A. Manning, J. Clark and David McGee. This work was supported in part by NSF-EAR-1702704, NSF-EAR-1702571, and NSF-OCE-1923915.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M.S. wrote the manuscript and carried out modelling and data analysis. J.N. and A.M.S. created the database. J.P.S. developed the LGM atmospheric pressure model. A.M.S., J.N., W.A., M.S., J.T.K. and R.K. contributed groundwater datasets, all authors contributed to weekly discussions about data interpretation and modelling. All authors edited and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature thanks Jordan Clark, Andrew Manning, David McGee and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

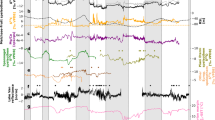

Extended Data Fig. 1 Evaluation of leading noble gas models.

Comparison of Late Holocene NGTs to ERA5-Land 1981–2019 MASTs across three NGT models and χ2 goodness-of-fit histogram comparison of all groundwater samples (n = 753) included in this work (normalized by degrees of freedom, n) (inset). The closed-system equilibration (CE) model agrees closest with ERA5-Land temperatures (r.m.s.d. = 1.4 °C), followed by the partial re-equilibration (PR) (r.m.s.d. = 1.5 °C) and oxygen depletion (OD) (r.m.s.d. = 5.7 °C) models. The closed-system equilibration model also exhibits the best goodness-of-fit (lowest median χ2/n). Data are mean ± 1 s.e.m.

Extended Data Fig. 2 ERA5-Land temperatures are unbiased above 5 °C.

Comparison of 1981–2019 mean annual ERA5-Land ground (upper soil) temperatures to a global database of modern mean annual measured ground temperatures34, using the approach described in the Methods to project ERA5-Land temperatures to the observation elevations. Whereas below approximately 5 °C, ERA5-Land temperatures appear to be systematically biased to be warmer than the observed temperature, above 5 °C they consistently overlap the 1:1 line with an r.m.s.d. of 1.6 °C. Observed temperatures tend to be slightly warmer than ERA5-Land temperatures on average, perhaps because of the typical locations of micrometeorological stations in barren fields, with little cooling from the shade provided by vegetation.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Leading sources of systematic error in LGM noble gas palaeothermometry.

a–d, Modelled sensitivity of apparent NGTs to leading sources of systematic error. In each case, NGT bias (T′) is reported with respect to a starting recharge temperature of 10 °C at 1 km elevation (except for mixing tests (d) in which T′ is given relative to the temperature of an equal-parts mixture of 10 °C equilibrated water with a given equilibrium mixing end-member temperature). The NGT bias associated with a source of error is shown, including LGM–Late-Holocene changes in recharge elevation (a), water table depth (ΔWTD, b) and pressure (ΔP, c), and the direct NGT bias induced by mixing (d) relative to the admixture temperature. Green squares indicate the ±1σ confidence region for the range of likely glacial–interglacial variability (Supplementary Table 1; see Methods for a detailed description of each sensitivity test and Supplementary Table 2 for a compilation of the results).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Atmospheric pressure changes during the LGM.

Box model result for changes in LGM atmospheric pressure with elevation at a fixed point. a, The absolute pressure (P) is shown during the LGM and in the modern atmosphere. b, LGM anomalies in pressure (ΔP) relative to the modern atmosphere are shown. In brief, the model assumes a fixed lapse rate (6.5 °C km−1) and uses the barometric equation to estimate the vertical distribution of atmospheric pressure during the LGM, accounting for loss of atmospheric air by dissolution into a colder ocean and occlusion in high-latitude ice sheets, as well as displacement of air by the growth of large ice sheets (see Methods for further details).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Comparison of AP2 LGM cooling estimates to literature values.

Comparison by latitude of noble-gas-derived ΔTLGM (this study, approach AP2) to zonal-mean land-surface (solid lines) and sea-surface (dashed lines) estimates of ΔTLGM from key previous studies1,5,7. Data are mean ± 1 s.e.m. Our AP2 low latitude (45° S–35° N) mean estimate of LGM cooling (4.8 ± 0.6 °C; thick green dashed line, with 95% confidence error envelope) is around 1 °C smaller in magnitude (warmer) than AP1. Although the AP2 estimate seems to more closely overlap the previously published land cooling data1, we note that this data-assimilation study was entirely constrained by marine proxies and therefore the implications for cooling over land should be treated with caution. For the physical and statistical reasons described in the main text, we suggest that AP1 is more robust, and we emphasize that the relatively good agreement between AP1 and AP2, compared with the range of disagreement among literature values, adds confidence to the reliability of the NGT reconstruction.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Seltzer, A.M., Ng, J., Aeschbach, W. et al. Widespread six degrees Celsius cooling on land during the Last Glacial Maximum. Nature 593, 228–232 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03467-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03467-6

This article is cited by

-

Humid and cold forest connections in South America between the eastern Andes and the southern Atlantic coast during the LGM

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Southern Ocean glacial conditions and their influence on deglacial events

Nature Reviews Earth & Environment (2023)

-

Holocene thermal maximum mode versus the continuous warming mode: Problems of data-model comparisons and future research prospects

Science China Earth Sciences (2023)

-

Early LGM Environments Accelerated the MSA/LSA Transition in Southern African Highlands: the Robberg’s Emergence at Melikane (Lesotho)

Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology (2023)

-

The deglacial forest conundrum

Nature Communications (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.