Abstract

Radiative heat transfer (RHT) has a central role in entropy generation and energy transfer at length scales ranging from nanometres to light years1. The blackbody limit2, as established in Max Planck’s theory of RHT, provides a convenient metric for quantifying rates of RHT because it represents the maximum possible rate of RHT between macroscopic objects in the far field—that is, at separations greater than Wien’s wavelength3. Recent experimental work has verified the feasibility of overcoming the blackbody limit in the near field4,5,6,7, but heat-transfer rates exceeding the blackbody limit have not previously been demonstrated in the far field. Here we use custom-fabricated calorimetric nanostructures with embedded thermometers to show that RHT between planar membranes with sub-wavelength dimensions can exceed the blackbody limit in the far field by more than two orders of magnitude. The heat-transfer rates that we observe are in good agreement with calculations based on fluctuational electrodynamics. These findings may be directly relevant to various fields, such as energy conversion, atmospheric sciences and astrophysics, in which RHT is important.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

$199.00 per year

only $3.90 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Change history

05 March 2019

We would like to correct the sentence in our Letter “However, both our detailed computational analysis (see Supplementary Fig. 2) and past computations13–15 suggest that such enhancements are not anticipated for metallic spheres, and very small increases (by a factor of a few) may be expected for dielectric spheres or metallic cylinders.” The work of ref. 13 is not limited to the structures described in this statement but also presents a computational study of radiative heat transfer between rectangular dielectric membranes that is consistent with our experimental and computational analysis, and supports our findings that the blackbody limit can be overcome in the far-field. See accompanying Amendment. The original Letter has not been corrected online.

References

Chandrasekhar, S. Radiative Transfer (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1950).

Planck, M. The Theory of Heat Radiation [transl. Masius, M.] (P. Blakiston’s Son & Co., Philadelphia, 1914).

Modest, M. F. Radiative Heat Transfer 3rd edn (Academic Press, New York, 2013).

Kim, K. et al. Radiative heat transfer in the extreme near field. Nature 528, 387–391 (2015).

Song, B. et al. Radiative heat conductances between dielectric and metallic parallel plates with nanoscale gaps. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 509–514 (2016).

Shen, S., Narayanaswamy, A. & Chen, G. Surface phonon polaritons mediated energy transfer between nanoscale gaps. Nano Lett. 9, 2909–2913 (2009).

Rousseau, E. et al. Radiative heat transfer at the nanoscale. Nat. Photon. 3, 514–517 (2009).

Reipurth, B., Jewitt, D. & Keil, K. (eds) Protostars and Planets V (Univ. Arizona Press, Tucson, 2007).

Raman, A. P., Anoma, M. A., Zhu, L., Rephaeli, E. & Fan, S. Passive radiative cooling below ambient air temperature under direct sunlight. Nature 515, 540–544 (2014).

Guler, U., Boltasseva, A. & Shalaev, V. M. Refractory plasmonics. Science 344, 263–264 (2014).

Ben-Abdallah, P. & Biehs, S.-A. Near-field thermal transistor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 044301 (2014).

Otey, C. R., Lau, W. T. & Fan, S. Thermal rectification through vacuum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 154301 (2010).

Fernández-Hurtado, V., Fernández-Domínguez, A. I., Feist, J., García-Vidal, F. J. & Cuevas, J. C. Super-Planckian far-field radiative heat transfer. Phys. Rev. B 97, 045408 (2018).

Golyk, V. A., Krüger, M. & Kardar, M. Heat radiation from long cylindrical objects. Phys. Rev. E 85, 046603 (2012).

Kattawar, G. & Eisner, M. Radiation from a homogeneous isothermal sphere. Appl. Opt. 9, 2685–2690 (1970).

Biehs, S.-A. & Ben-Abdallah, P. Revisiting super-Planckian thermal emission in the far-field regime. Phys. Rev. B 93, 165405 (2016).

Au, Y.-Y., Skulason, H. S., Ingvarsson, S., Klein, L. J. & Hamann, H. F. Thermal radiation spectra of individual subwavelength microheaters. Phys. Rev. B 78, 085402 (2008).

Schuller, J. A., Taubner, T. & Brongersma, M. L. Optical antenna thermal emitters. Nat. Photon. 3, 658–661 (2009).

Wuttke, C. & Rauschenbeutel, A. Thermalization via heat radiation of an individual object thinner than the thermal wavelength. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 024301 (2013).

Hochbaum, A. I. et al. Enhanced thermoelectric performance of rough silicon nanowires. Nature 451, 163–167 (2008).

Kim, P., Shi, L., Majumdar, A. & McEuen, P. L. Thermal transport measurements of individual multiwalled nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 87, 215502 (2001).

Sadat, S. et al. Room temperature picowatt-resolution calorimetry. Appl. Phys. Lett. 99, 043106 (2011).

Sadat, S., Meyhofer, E. & Reddy, P. Resistance thermometry-based picowatt-resolution heat-flow calorimeter. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 163110 (2013).

St-Gelais, R., Zhu, L. X., Fan, S. H. & Lipson, M. Near-field radiative heat transfer between parallel structures in the deep subwavelength regime. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 515–519 (2016).

Polder, D. & Van Hove, M. Theory of radiative heat transfer between closely spaced bodies. Phys. Rev. B 4, 3303–3314 (1971).

Rytov, S. M., Kravtsov, I. A. & Tatarskii, V. I. Principles of Statistical Radiophysics 2nd edn (Springer, Berlin, 1987).

Otey, C. R., Zhu, L., Sandhu, S. & Fan, S. Fluctuational electrodynamics calculations of near-field heat transfer in non-planar geometries: a brief overview. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 132, 3–11 (2014).

Rodriguez, A. W., Reid, M. H. & Johnson, S. G. Fluctuating-surface-current formulation of radiative heat transfer for arbitrary geometries. Phys. Rev. B 86, 220302 (2012).

Cataldo, G. et al. Infrared dielectric properties of low-stress silicon nitride. Opt. Lett. 37, 4200–4202 (2012).

Reid, M. T. H. & Johnson, S. G. Efficient computation of power, force and torque in BEM scattering calculations. IEEE Trans. Antenn. Propag. 63, 3588–3598 (2015).

Goody, R. M. & Yung, Y. L. Atmospheric Radiation: Theoretical Basis 2nd edn (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, 1989).

Draine, B. & Weingartner, J. C. Radiative torques on interstellar grains: I. Superthermal spinup. Astrophys. J. 470, 551–565 (1996).

Sultan, R., Avery, A., Stiehl, G. & Zink, B. Thermal conductivity of micromachined low-stress silicon-nitride beams from 77 to 325 K. J. Appl. Phys. 105, 043501 (2009).

Lee, S.-M. & Cahill, D. G. Heat transport in thin dielectric films. J. Appl. Phys. 81, 2590–2595 (1997).

Kennard, E. H. Kinetic Theory of Gases, with an Introduction to Statistical Mechanics (McGraw-Hill, New York, 1938).

Horowitz, P. & Hill, W. The Art of Electronics (Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 1989).

Acknowledgements

P.R. and E.M. acknowledge support from the Office of Naval Research under award number N00014-16-1-2672 (device fabrication), from the Army Research Office under award number W911NF-18-1-0004 (computational modelling) and from Department of Energy Basic Energy Sciences under award number DE-SC0004871 (instrumentation for radiative measurements). M.M.Q. is grateful for support from the National Science Foundation under award number DMR-1255156 (characterization of dielectric functions). L.Z. thanks C. R. Otey for discussions. We acknowledge the Lurie Nanofabrication Facility for facilitating the fabrication of the devices and the Advanced Research Computing Technology Services at the University of Michigan for computational resources.

Reviewer information

Nature thanks P. Bharadwaj and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.R. and E.M. conceived the work. D.T., R.M. and S.S. fabricated the devices and performed the RHT experiments. L.Z. performed the calculations. Z.X. and P.M. performed spectroscopic measurements of the dielectric functions of silicon nitride under the guidance of M.M.Q. The manuscript was written by D.T., L.Z., P.R. and E.M. with comments and input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data figures and tables

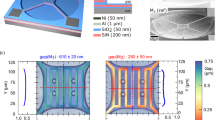

Extended Data Fig. 1 Fabrication of the devices.

a, Step 1: deposition of the silicon nitride (SiN) layer on a silicon handle wafer. Step 2: patterning of the Pt serpentine resistance thermometer. Step 3: patterning of gold leads. Step 4: front-side etching of suspended device contour. Step 5: etching of a window in SiN on the back side of the device. Step 6: potassium hydroxide (KOH) etching of silicon handle to release the suspended devices. Step 7: optional PECVD of SiN onto suspended 1,998-nm-thick devices to create even thicker membranes (6,712 and 11,405 nm thick). b, c, Scanning electron microscope (b) and optical microscope (c) images showing the geometry of the fabricated devices and relevant dimensions. Au wires (yellow) and suspended membranes (red and blue) were pseudo-coloured.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Characterization of the flatness and coplanarity of adjacent membranes.

a–d, Data from laser scanning confocal microscope scans across adjacent membranes showing the flatness of 270-nm-thick (a), 486-nm-thick (b), 6,712-nm-thick (c) and 11,405-nm-thick (d) membranes. Line profiles were taken over the red dashed line indicated in the surface plots in the insets.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Characterization of the electrical and thermal properties of the devices.

a, Temperature dependence of the resistance of the integrated PRT near room temperature. The inset shows a schematic of the measurement scheme used for resistance characterization. b, Thermal frequency response of membrane devices with various thicknesses measured at T = 300 K. The inset depicts a schematic of the measurement scheme employed for these tests. c, Temperature rise of the membrane as a function of the Joule heating in the PRT, measured at T = 300 K for devices of various thicknesses. d, Temperature rise of the receiver membrane as a function of the temperature increase of the emitter membrane for a 2-μm-thick device at 100 K. The noise-equivalent temperature is about 60 μK for a temperature modulation frequency of 0.5 Hz and a measurement bandwidth of 0.78 mHz, and Idc = 10 μA.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Quantification of parasitic energy transfer mechanisms.

a, Measured Grad,eff between 2-μm-thick SiN membranes at various temperatures and pressures. Measurements performed at 10−3 torr (black squares) and 10−6 torr (red diamonds) give virtually identical results, strongly supporting the expectation that conduction via remaining gas molecules plays no role. b, Measured Grad,eff between 270-nm-thick SiN membranes at various temperatures. The inset illustrates how thermal energy between the devices can potentially couple via conduction through the substrate. The plotted data correspond to two device geometries: devices with 400-μm-long support beams (black squares) and devices with 150-μm-long support beams (red squares). Because devices with short and long beams have identical Grad,eff, it is clear that coupling via the suspending beams is negligibly small. c, Schematic describing the control experiment, where an emitter and a receiver are separated by a gap of about 1 mm and an Al foil is placed between them, blocking direct RHT (not drawn to scale and proportion). d, Measured coupling signal between 2-μm-thick emitter and receiver membranes across a 1-mm-wide gap (T = 300 K). Signals without (black squares) and with (red circles) an Al foil in the gap are shown. The inset (cross-sectional view of the devices) illustrates how the Al foil shield blocks direct RHT between the membranes but potentially allows RHT via specular reflections. Because the signal obtained in the presence of the Al blocker represents the noise floor of our measurement, we conclude that there is negligible heat transfer (via RHT or otherwise) in the presence of the Al foil. This control experiment provides unequivocal evidence that energy transfer between the membranes is mediated exclusively by direct radiation. e, Scanning electron microscope image of two emitter and receiver pairs suspended in separate through-holes on the same handle substrate. f, Measured coupling signal between 486-nm-thick devices (T = 100 K). Signals from adjacent emitter and receiver devices (that is, in the same through-hole; see pair 1 in e) with a 20-μm-gap (black squares) are compared with the signals measured when the emitter and receiver devices are suspended in separate through-holes on the same silicon handle substrate (red circles).

Extended Data Fig. 5 Radiative conductance for devices with 486-nm-thick and 6,712-nm-thick membranes.

a, Grad,eff as a function of temperature. Experimental measurements (solid symbols) are compared with values calculated using FED (open symbols) and COMSOL-modelled blackbody values (dashed lines). b, BEM calculation of the normalized spectral radiative conductance at 300 K. The spectral conductance values are normalized by the thickness of each device.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

This file contains Supplementary Text, Supplementary Figures 1–20 and Supplementary References

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thompson, D., Zhu, L., Mittapally, R. et al. Hundred-fold enhancement in far-field radiative heat transfer over the blackbody limit. Nature 561, 216–221 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0480-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0480-9

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Incandescent temporal metamaterials

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Low-dimensional heat conduction in surface phonon polariton waveguide

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Remarkable heat conduction mediated by non-equilibrium phonon polaritons

Nature (2023)

-

Transport in electron-photon systems

Frontiers of Physics (2023)

-

Physical limits in electromagnetism

Nature Reviews Physics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.