Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) vaccine research has reached a unique point in time. Breakthrough findings in both the basic immunology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection and the clinical development of TB vaccines suggest, for the first time since the discovery of the Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccine more than a century ago, that a novel, efficacious TB vaccine is imminent. Here, we review recent data in the light of our current understanding of the immunology of TB infection and discuss the identification of biomarkers for vaccine efficacy and the next steps in the quest for an efficacious vaccine that can control the global TB epidemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is among the top ten causes of death overall and is the leading cause of death owing to infection with a single type of pathogen1. It is estimated that almost one-quarter of the global population, between 2 billion and 3 billion people, has been infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) and may be at risk of progression to TB2. Up to 80% of the lifetime risk of progression to disease is thought to occur in the first 2 or 3 years after infection3. In 2017, an estimated 10 million people developed TB and 1.6 million people died from the disease1.

It is now appreciated that Mtb infection does not represent a single, uniform state and that the historical division of TB into either latent (latent TB infection (LTBI)) or active TB has gravely underappreciated the complex and dynamic nature of the host–pathogen interactions4,5,6. Progression from Mtb infection to clinical disease appears to transition via a number of continuous asymptomatic infection states that have previously been classified as LTBI, which include the asymptomatic states recently termed incipient TB and subclinical TB, before active, clinical TB disease manifests7,8. Further, within an individual host, Mtb-infected lesions in the lung or draining lymph nodes do not develop in a uniform synchronized manner but independently and therefore represent a spectrum of pathology that can span all stages from sterile, calcified granulomas through to caseous, necrotic lesions with exceedingly high bacterial burdens9. It is important to consider both the complexity of the human–Mtb interactions and the magnitude and diversity of the global epidemic as a backdrop to the challenges faced by vaccine development. Given that in some high incidence areas the majority of the adult population is infected, classic prophylactic vaccination (before any exposure to the pathogen) is applicable for only a proportion of the individuals in need. Therefore, TB vaccine development efforts are currently focused on developing vaccines for the following administration regimens: prophylactic vaccination, which is a vaccine administered to individuals in order to prevent Mtb infection or clinical disease (prophylactic vaccines can be either priming vaccines such as Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) (see Box 1) used in neonates or booster vaccines for later administration); postexposure vaccination, which is a vaccine administered to Mtb-infected individuals to prevent the development of active disease (many priming and booster vaccines are currently developed for postexposure administration owing to their ability to boost and supplement the naturally occurring infection-promoted responses); and therapeutic vaccination, which is a vaccine administered to individuals with clinical disease in combination with or after antibiotic treatment to prevent recurrence of disease. Development of both prophylactic and postexposure vaccines is actively being pursued with several candidates in clinical trials, but therapeutic vaccines are also receiving increasing attention.

Five years ago, the results of a large phase IIb efficacy trial of the first TB booster vaccine candidate tested in infants were published. Vaccination of 4–6-month-old infants, who had received neonatal BCG vaccination, with MVA85A induced no additional protection against Mtb infection or active TB beyond that observed in the placebo arm of the study10. This result was a great disappointment to both the TB vaccine research community and funders and a call to action for researchers in basic and applied vaccine development. Today, we are witnessing immense progress in both preclinical and clinical TB vaccine research, including the first proof-of-concept study showing that revaccination with BCG can protect adolescents from sustained Mtb infection11 and that the subunit vaccine M72/ASO1E provides protection against the development of TB disease in Mtb-infected adults12. Here, we discuss recent breakthroughs in our understanding of the mechanism of protective immune responses, provide an overview of the vaccine candidates in clinical trials and discuss whether it is time to reconsider BCG revaccination as part of a future improved TB vaccine strategy.

Immune responses to Mtb

Mtb can establish infection in susceptible individuals after the inhalation of a single or a few bacteria that are taken up by alveolar macrophages. The pathogen has developed a refined set of evasion mechanisms that delay bacterial transport to the regional lymph node and allow it to evade host cellular immunity, giving it sufficient time to establish a productive infection13,14,15. The result is a delayed onset of the natural adaptive immune response observed both in animal models of TB16 and in human clinical TB17,18.

One of the primary roles of vaccination is to establish efficient and long-lived immune memory in order to shorten the interval between infection and the onset of an adaptive immune response at the site of infection, such that the infection can be controlled rapidly and spreading to secondary sites is avoided. In humans, the first exposure to Mtb typically occurs after the immune response has been primed by other mycobacterial encounters, either in the form of BCG vaccination or environmental mycobacteria. As a result, TB vaccine strategies should consider how prior induction of T cells (and other immune responses) by these exposures may influence the function, trafficking and survival of vaccination-induced responses and their effectiveness against Mtb. Furthermore, in settings with very high rates of Mtb infection, such responses must be able to resist the effects of repeated reinfection and long-term continuous antigen exposure from this chronic infection.

The role of CD4+ T cells

Recent data in animal models suggest that vaccine-induced CD4+ cells of the T helper 17 (TH17) cell subtype, which naturally traffic to the airways, can accelerate the recruitment of protective TH1 cells19,20,21. In fact, a recent study of a rhesus macaque model of pulmonary vaccination showed that vaccination with BCG induces pulmonary TH1 cells and/or TH17 cells, which co-express IFNγ, TNF, IL-2 and IL-17 and protect against infection upon repeat low-dose challenge with Mtb22. When CD4+ T cells arrive at the site of infection, they encounter aggregates of Mtb-containing macrophages and other immune cells and together form the tight cellular structure referred to as the granuloma. The CD4+ T cells secrete cytokines, which activate infected macrophages to control bacterial growth and attract more immune cells to the granuloma (reviewed elsewhere23).

Most vaccine research has focused on TH1 cells and the effector cytokine IFNγ as a readout for successful vaccination and a potential indicator of vaccine efficacy. However, it is clear from animal studies22,24,25 that expansion beyond the narrow focus on IFNγ is necessary to identify new biomarkers (also called immune correlates of protection (COP); see Box 2) to support vaccine evaluation and optimization. This is also supported by conflicting data on the role of IFNγ in human studies. A study of COP in the participants of the MVA85A phase IIb trial suggested that higher frequencies of BCG-reactive IFNγ-secreting cells, as quantified by ELIspot assay, were associated with a reduced risk of developing TB26. By contrast, the MVA85A booster vaccine referred to above induced long-lived CD4+ T cells that co-expressed IFNγ, TNF and IL-2 (ref.27), a functional subset of cells termed polyfunctional by many in the field, but this subset did not afford protection10. Similarly, in a study of 10-week-old infants that were vaccinated with BCG at birth, there was no association between the frequencies of BCG-reactive TH1 cells or the co-expression patterns of IFNγ, TNF and IL-2 of these cells and subsequent risk of developing TB10,26,27,28. Collectively, these studies suggest that TH1 cell responses are necessary but not sufficient to mediate protection against Mtb and that other functions and characteristics of T cells, and perhaps other arms of immunity, are involved in protection against TB.

Recently, the expression of CD153, a surface molecule of the TNF superfamily that is expressed by Mtb-specific CD4+ T cells during infection, was suggested as a promising marker of protection in animal models. CD153 was also found to be expressed by Mtb-specific CD4+ T cells in humans who successfully control Mtb infection29. This molecule is an example of the new candidate biomarkers of protective immunity that should be considered in analyses of immune COP in the context of vaccine trials.

The role of CD8+ cells

Mtb-specific CD8+ T cell responses increase during disease progression with kinetics that appear to positively correlate with the bacterial burden30,31, but their role in protective immunity to Mtb is unclear. Evidence that CD8+ cells may play a protective role comes from a non-human primate (NHP) study in which CD8+ T cells were depleted, which resulted in compromised BCG vaccine-induced immune control of Mtb32. However, recent data from murine models suggest that even very high numbers of vaccine-induced CD8+ T cells that are specific for antigens involved in protective immunity fail to recognize Mtb-infected macrophages or affect Mtb proliferation in animal infection studies33,34. Similarly, antigen-specific CD8+ T cells induced by an adenovirus-based TB vaccine in humans failed to recognize Mtb-infected dendritic cells in vitro35. Although the subject of numerous studies, the role of CD8+ T cell responses in protective immunity against TB therefore still remains unresolved.

The role of B cells

Antigen-specific antibodies, and their functional attributes in immunity against Mtb, have recently received increasing attention. Compelling evidence shows marked differences in the plasma levels of natural mycobacteria-specific IgG or IgA and their glycosylation profiles and Fc functions when comparing individuals with LTBI and patients with active TB36,37. Further, a recent study of a rhesus macaque model of pulmonary BCG vaccination showed that high levels of antigen-specific IgA in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid were associated with protection against Mtb infection and disease22.

Mtb escape mechanisms

In addition to delaying the onset of adaptive immune responses, Mtb has also evolved a set of escape mechanisms aimed at inhibiting CD4+ T cell activation during later stages of the infectious process38. Examples include the downregulation of certain target antigens to very low levels39 and the active transfer of immunodominant antigens to uninfected bystander dendritic cells and macrophages40. The outcome of this host–pathogen stand-off is bacterial survival in a state of latent infection. It is notable that established latent infection seems to provide significant protection against reinfection in classical epidemiological studies41,42 and in NHP models43, a phenomenon that provides evidence for protective natural immunity against Mtb. We note that it is possible that immune mechanisms necessary for protection against the establishment of Mtb infection may be different from those required for successful long-term containment of an established Mtb infection such that progression to disease is averted. Ongoing studies of vaccine-induced COP, described below, will provide important insights into this.

The diversity of the CD4+ T cell response to tuberculosis

For protection against TB, the CD4+ T cell subset is of major interest. CD4+ T cells differentiate into T central memory (TCM) cells that home to secondary lymphoid organs and, on the basis of their expression of adhesion molecules, most likely also to inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue structures in the lung44. Upon antigen re-exposure, TCM cells differentiate into T effector memory (TEM) cells and effector cells of either the TH1 cell or TH17 cell lineage that migrate to and exert their effector functions in infected tissues (see Fig. 1). A proportion of these T cells subsequently remains in the lung as T tissue-resident memory (TRM) cells. An efficient frontline defence in the lung depends on both TRM cells localized in the lung before infection and newly recruited T effector (TEFF) cells that arrive after infection. However, for a chronic infection such as Mtb, the longevity of the immune response, that is, the ability to withstand the continuous exposure to antigen for very long periods without exhaustion, is likely of equal importance. This is where T stem cell memory (TSCM) cells and TCM cells play a central role because their proliferative potential can maintain the supply of tissue-homing T cells. Designing TB vaccine strategies therefore requires careful consideration of the distribution of different subsets of CD4+ T cells, how they respond to repeated antigen exposure during persistent infection and their ability to traffic to and be retained within the lung, both before and during ongoing Mtb infection.

After Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) infection of alveolar macrophages (red arrows), Mtb is transported to lung-draining lymph nodes by infected dendritic cells, initiating T cell priming or triggering the activation of pre-existing memory T cells, which appears to preferentially drive T cell differentiation towards late-stage T effector memory (TEM) cell and T effector (TEFF) cell responses. Ongoing antigen expression is likely a driver of this T cell differentiation process, which favours primarily IFNγ -expressing and/or TNF-expressing T cells and little IL-2 expression. Vaccine administration in the skin or muscle promotes antigen uptake by dendritic cells, which traffic to draining lymph nodes to prime or activate T cells (blue arrows). In the case of subunit protein-adjuvant vaccines, the resulting T cell responses appear to be dominated by less differentiated T central memory (TCM) cell responses; these cells primarily express IL-2 and/or TNF. Achieving long-lived protective immunity by vaccination may require the establishment of a careful balance between TCM cell and TEM cell responses, such that a durable pool of memory cells resides in secondary lymphoid tissues while an appropriate tissue-resident population with rapid effector function is maintained in peripheral airway tissues.

In humans, Mtb infection promotes the development of CD4+ T cells that span a range of differentiation states, from the most early TSCM CD4+ cells45 through to fully differentiated TEFF cells that predominantly express IFNγ46,47,48. Many factors are likely to determine where in this range a given specific T cell response will lie, including the expression level of the particular Mtb antigen that is targeted, the stage of disease progression or host–pathogen interaction and the location of the T cell itself. In order to allow a conclusive interpretation of results, it is therefore essential that human studies of T cell function and differentiation clearly and carefully characterize the clinical phenotype of study participants to define infection stage. Overall, an increasing mycobacterial load correlates with progressive differentiation of Mtb-specific CD4+ T cell responses away from TCM cells that secrete IL-2 and towards TEFF cells that secrete predominantly IFNγ46,47,48,49. In animal models of Mtb infection, ongoing antigen exposure is a significant challenge for the host immune system and results in CD4+ T cell exhaustion through inhibitory receptors such as TIM3 (also known as HAVCR2)50 and the upregulation of exhaustion markers such as killer-like lectin receptor G1 (KLRG1)51. This results in the loss of self-renewing TCM cell subsets and in functional impairment, eventually resulting in uncontrolled growth of Mtb52. In TB vaccine studies in the mouse model, it has become clear that T cell responses promoted by an adjuvanted vaccine formulation typically differ from Mtb-induced T cell responses in that they preferentially induce IL-2-producing TCM cells. Compared with TEM cells and TEFF cells induced by continuous exposure to Mtb, these TCM cells are less likely to become terminally differentiated, predominantly IFNγ-secreting KLRG1+ T cells (Fig. 1).

Such vaccine-induced T cells therefore have the desirable ability to resist terminal differentiation, which would eventually result in functional impairment and depletion of the Mtb-specific T cell pool48,49,52. Animal models of TB that investigated T cell differentiation have demonstrated that BCG vaccination, similarly to Mtb infection, pushes T cell differentiation towards TEFF cells, which results in a failure to efficiently maintain long-term protection against Mtb53,54.

Initially, the main role of less differentiated CD4+ T cells (such as TCM cells and TSCM cells) was thought to relate exclusively to their ability to resist differentiation, replenish TEM cells and maintain long-lived memory both before and after infection. Recent insights into T cell migration patterns have added important new facets to this interpretation. Using an intravascular staining technique, a less differentiated memory subset of T cells, which expresses the checkpoint molecule PD1 and the chemokine receptor CXCR3, was shown to enter the Mtb-infected lung parenchyma55. By contrast, the more differentiated TEFF cell subsets, characterized by the expression of KLRG1 and the fractalkine receptor CX3CR1, lose their ability to enter the lung parenchyma and to protect against Mtb55. The negative influence of a highly differentiated and strongly TH1 cell-polarized response on protection against Mtb is further supported by recent data from experimental animal models that investigate this question from different angles56,57,58.

Choosing the best antigens

Two critical and as yet unresolved questions in TB vaccinology are how to select the best antigens and how many antigens to include in a vaccine. The retrospective analysis of the phase IIb clinical trial of the MVA85A booster vaccine, which contains a single antigen (Ag85A), highlights this question59,60. Given that earlier studies had shown that Ag85A is expressed at only low levels during chronic Mtb infection in mouse models61,62, it is possible that the disappointing results were due to poor antigen choice61,62. Some of the most vaccine-relevant T cell antigens are virulence factors such as those associated with the ESX1 protein secretion system, which is instrumental for pathogen survival and is expressed at high levels in vivo during both the acute and chronic phase of infection61,62,63. Although one might assume that this high level of expression might indicate suitability as an immune target, immune responses to highly expressed antigens may eventually become exhausted during chronic infection. An unanswered question is whether repeated exposure or reinfection in humans who live in high-transmission settings also drives T cell exhaustion. Interestingly, most of the immunodominant antigens are conserved, with minimal sequence variation among different clinical strains of Mtb, indicating that the induction of T cell exhaustion may be an integral part of the Mtb survival strategy64,65,66. In a direct comparison between T cell responses specific for the ESAT6 antigen (which shows high and continuous expression during Mtb infection) and Ag85B (which is primarily expressed early during infection), the different expression profiles were found to have a profound influence on the quality of the immune response. Ag85B-specific T cells developed into classical CCR7+KLRG1− TCM cells after primary Mtb infection in mice, whereas ESAT6-specific T cells were maintained in an effector state and gradually increased their expression of KLRG1 and lost IL-2 expression54,63. Similar differences between the differentiation state and functional capacity of human ESAT6-specific and Ag85B-specific CD4+ T cells were also observed in healthy trial participants with LTBI who were vaccinated with the H1:IC31 or H56:IC31 vaccines, which contain both antigens63.

These findings are in agreement with previous reports of the influence of antigen persistence and load on the distribution of different subsets of human memory T cells in clinical studies of other infections or vaccines67. A vaccine that provides a single exposure to an antigen followed by antigen clearance, such as the tetanus vaccine, primarily induces IL-2-producing TCM cells, whereas pathogens that cause contained infections that provide low but persistent antigen exposure, such as herpes simplex virus 1, induce TEM cells that express IFNγ, TNF and low levels of IL-2 (ref.67). TEFF cells that express only IFNγ on the other hand are induced by infections such as cytomegalovirus that provide high and persistent antigen exposure67.

Striking the balance to achieve longevity and efficacy

As discussed above, excessive induction of TEFF cells by a vaccine modality or its antigen components may lead to impaired maintenance of memory and functional ability of the immune response, and, in the most extreme case, with very high expression of effector cytokines, such as IFNγ or IL-17, the result can be immunopathology68,69,70,71. TB vaccine strategies therefore need to strike an optimal balance between the self-renewing TSCM cell and TCM cell subsets and the more differentiated TEM cell and TEFF cell subsets that provides an efficient first-line defence in the lung (Fig. 1). This is complicated by the large proportion of individuals with LTBI (in some high-endemic regions more than 50% of the population)2 and extensive reinfection in high-transmission settings. Individuals with LTBI have an already established T cell response and represent a challenging population in which vaccine modalities and doses intended for initial priming in naive hosts may be suboptimal72. A recent analysis of the literature on the pathogenesis of human TB before antibiotics were introduced furthermore suggests that immune responses required to prevent progression to reactivation TB (that is, progression of established LTBI to active disease) are likely to be different from those required to control or prevent the establishment of the primary infection9. This follows from the argument that, in the case of progression to reactivation TB, a successful immune response would need to protect against tissue damage and cavitation. A recent interim analysis of the ongoing phase IIb trial of the subunit vaccine M72/ASO1E as a postexposure vaccine, which showed a vaccine efficacy of 54% against progression to TB relative to placebo12, clearly shows that efficacious vaccine modalities in pre-sensitized populations are possible. Delineating the functional, phenotypic and differentiation characteristics of T cell responses induced by the two antigens in this vaccine (Mtb32A and Mtb39A) will be critical for our understanding of immune COP against TB.

Tuberculosis vaccines in clinical trials

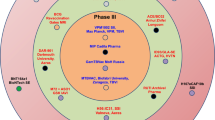

The development of an efficacious TB vaccine strategy relies on a healthy pipeline of TB vaccine candidates that represent a diverse repertoire of formulations and mycobacterial antigens and that induce a broad range of immune responses with different characteristics. Eleven TB vaccine candidates (Table 1) are currently in clinical testing for prophylactic, postexposure or therapeutic indications.

Whole cell vaccines — live

Live, attenuated whole cell vaccines were initially developed as prophylactic, priming vaccines with the aim to replace BCG-prime vaccination in infants, but they are now also being assessed as postexposure vaccines in adolescents and adults. Two of these vaccines, the recombinant BCG vaccine VPM1002 and the live, attenuated Mtb vaccine MTBVAC, are currently in clinical trials. Both induce a complex and diverse immune response to many antigens, which may offer an advantage over subunit vaccines that have a response restricted to a few antigens. However, such live vaccines are likely to be subject to the same interference caused by prior immunological sensitization by non-tuberculosis mycobacteria (NTMs) as reported for BCG. VPM1002 is also being assessed as a postexposure vaccine for the prevention of recurrence of active TB.

Whole cell vaccines — inactivated

On the basis of a classical vaccine development paradigm, these products, which include RUTI, Mycobacterium vaccae-based vaccines and the Mycobacterium obuense-based DAR-901 vaccine, utilize killed whole mycobacterial cells or mycobacterial cell extracts to safely induce complex immune subsets against multiple Mtb antigens. RUTI and M. vaccae-based vaccines are primarily being pursued as therapeutic vaccines, while DAR-901 is being developed as both a prophylactic and a therapeutic vaccine.

Adjuvanted protein subunit vaccine

Subunit vaccines are based on protein antigens administered with adjuvants. These are primarily developed as prophylactic or postexposure vaccines that boost responses that were initially primed by BCG or Mtb infection for preventing the establishment of Mtb infection, active TB or recurrent disease. Subunit vaccines that are currently in clinical testing include H4:IC31, H56:IC31, ID93 + GLA-SE and M72/AS01E. Some of these vaccines are also tested as therapeutic vaccines (for example, H56:IC31 and ID93 + GLA-SE) to prevent recurrence in patients who have completed chemotherapy for active TB.

Viral vectored vaccines

Live, attenuated, non-replicating viruses can be engineered to deliver genes encoding the antigens of interest into host cells. Such vaccines allow for the intracellular production of the antigen in vivo and activate cells of the innate immune system and therefore do not need to be adjuvanted. Viral vectored vaccines are being developed as both prophylactic vaccines and postexposure vaccines that boost responses primed by BCG or Mtb infection. A potential problem with viral delivery is the induction of vector-specific immunity that can interfere with subsequent booster vaccinations. Two viral vectored TB vaccine candidates, MVA85A and Ad5Ag85A, are currently in clinical testing in prime–boost combinations, including trials of the MVA85A candidate administered by aerosol to the airways.

BCG revaccination — time to reconsider?

Revaccination with BCG at different ages, but primarily in children, was practised for decades in several countries with limited evidence for its clinical value or cost-effectiveness73. Two large cluster-randomized controlled trials conducted in Brazil and Malawi evaluated BCG revaccination for the prevention of TB disease. Neither demonstrated efficacy74,75, resulting in World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations against this policy. Subsequent follow-up studies conducted as part of the REVAC study in Brazil have added a new layer of understanding to this disappointing result and suggest that prior mycobacterial sensitization is a major factor in preventing BCG revaccination efficacy in regions with a high prevalence of environmental mycobacteria exposure76 (Fig. 2). In the recent trial with the H4:IC31 subunit vaccine or BCG revaccination in Cape Town, South Africa, BCG revaccination provided significant protection (45% efficacy) against sustained Mtb infection (measured as prevention of sustained IFNγ release assay (IGRA) conversion for a follow-up period of 24 months in healthy adolescents who received a BCG prime in infancy)11. The readout of prevention of sustained IGRA conversion may be interpreted in different ways, which are all indicative of protective immunity: the prevention of primary infection, the accelerated clearance of the bacilli after infection, the long-term containment of the primary infection below the IGRA cut-off level or even the prevention of reinfection during the observation period. Regardless of the mechanistic interpretation of this readout, BCG revaccination resulted in a surprisingly high efficacy signal in this study. A plausible explanation for this observation most likely relates to the fact that individuals with Mtb-specific responses at enrolment, as measured by IGRA, were rigorously excluded11,77 and that Cape Town is thought to be an area with low to modest NTM exposure levels78. Compared with the REVAC study in Brazil, the main source of potential sensitization in this trial population therefore most likely came from remaining immune responses to neonatal BCG vaccination 12–16 years previously. So, even though pre-existing mycobacteria-specific T cell responses were found to be common in trial participants in the H4:IC31–BCG revaccination study, the results suggest that, without continuous high-level exposure from environmental mycobacteria or LTBI, the levels of immunity that persist from neonatal BCG vaccination are modest and do not block the efficacy of BCG revaccination significantly in adolescents (Fig. 2).

The hypothesized interaction between the magnitude of immune sensitization and vaccine efficacy by Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccination (red), adjuvanted protein subunit vaccines (orange) or a BCG-prime, subunit-boost strategy (blue) is shown. According to this model, BCG, and other live whole mycobacterial vaccines, are not efficacious in individuals with substantial prior immunological sensitization owing to latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI), recent BCG vaccination or exposure to atypical non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTMs) from the environment. Subunit vaccination, by comparison, would be efficacious in such a pre-sensitized population, as would a BCG-revaccination, subunit-boost strategy. In persons with low or no mycobacterial sensitization, the efficacy of BCG vaccination is significantly increased, and the efficacy of subunit vaccination will be largely independent of the levels of sensitization, but the BCG-revaccination, subunit-boost strategy may provide synergistic effects that result in enhanced vaccine efficacy.

This efficacy signal therefore opens up consideration of BCG revaccination in certain settings as part of an overall improved TB vaccination strategy as previously suggested78. Samples collected in the H4:IC31–BCG revaccination trial provide a unique opportunity to investigate whether the level of immune sensitization to NTMs at enrolment is associated with differences in the quality of the immune responses to the vaccine and/or protection against Mtb infection.

Building on recent subunit vaccine success

For the first time since the introduction of universal BCG vaccination into the WHO expanded programme for immunization in 1974, we have encouraging efficacy signals in trials of a TB vaccine11,12. In a phase IIb trial of healthy adolescents who received BCG in infancy but tested negative in the IGRA, vaccination with H4:IC31 was associated with 30.5% efficacy against sustained Mtb infection. This result was of statistical significance at the pre-defined statistical threshold of an 80% CI (3.0–52.0%), but not at a more rigorous 95% CI (–15.8% to 58.3%)11. Moreover, interim results of the ongoing phase IIb trial of M72/AS01E, conducted in 3,575 IGRA-positive adults, clearly illustrate that booster vaccination with a subunit vaccine can protect against TB disease in highly sensitized individuals with Mtb infection. This trial, which was conducted in HIV-negative adults from Kenya, Zambia and South Africa, most of whom received neonatal BCG, accrued 10 patients with microbiologically confirmed pulmonary TB into the M72/AS01E group and 22 patients into the placebo group, translating to an overall vaccine efficacy of 54.0% (95% CI 13.9–75.4%)12. An important consideration when interpreting the trial results of M72/AS01E is how the level of Mtb exposure and reinfection of trial participants may have influenced the efficacy of the subunit vaccine. A recent analysis of the incubation period of TB suggested that the vast majority of clinical TB cases occur early, within 1–2 years following Mtb infection or reinfection. This is different from reactivation of Mtb, which typically happens much later after a long period of latent infection3. The recent efficacy trial was conducted in settings with high Mtb infection rates where reinfection with Mtb is likely to be a frequent occurrence. Understanding whether the vaccine protected against reactivation disease or progression to disease following reinfection is likely to be important and will no doubt be the subject of investigation in coming years.

Whether the levels of efficacy observed in the H4:IC31–BCG and M72/AS01E trials are sufficient and persist long enough for programmatic implementation of the vaccines in their present form is an important question, especially because the reports from each trial followed trial participants for only 2 years. However, combined into a prime–boost strategy with BCG vaccination, novel subunit vaccines may promote a robust response that could significantly add to the efficacy of the BCG vaccine and compensate for its failures in sensitized populations. In accordance with the model in Fig. 2, induction of immunity by BCG is either blocked or masked by high levels of pre-existing T cell-mediated immune responses. By contrast, comparison of H56:IC31 or M72/ASO1E vaccination in naive versus LTBI individuals indicated that these subunit vaccines can markedly boost BCG-induced and Mtb-primed immune responses79,80,81. Therefore, a combined BCG revaccination and/or subunit vaccine strategy may have great potential in adult and/or adolescent populations.

Conclusion and future perspectives

The large number of different vaccine candidates and their advanced stages in clinical development denote a unique and exciting phase in TB vaccine research. There are also a large number of novel vaccine candidates in preclinical development, including more recently developed vaccine formats such as DNA vaccines, new adjuvants and delivery systems and combination vaccines. It is important that the most promising of these new candidates are advanced to efficacy studies in animals and clinical testing to augment the pipeline of TB vaccine candidates and concepts.

However, a notable limitation of the current clinical development landscape is a lack of inter-trial harmonization or standardization, which precludes a direct comparison of the immunological outcomes of different TB vaccine candidates. A recent analysis attempted to tackle this problem by comparing antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses induced by BCG and six of the novel TB vaccine candidates, including MVA85A, AERAS-402, H1:IC31, H56:IC31, M72/AS01E and ID93 + GLA-SE. The investigators retrieved published data on antigen-specific T cell responses from clinical trials completed in adolescents or adults at a single trial site in South Africa82. The results show that the magnitude of vaccine-induced TH1 cell-polarized CD4+ T cell responses measured several months after vaccination was the T cell response feature that diverged the most between the different candidates. Unlike the response magnitude, co-expression profiles of IFNγ, TNF and IL-2 by CD4+ T cells suggested a relative lack of functional diversity in responses induced by the different vaccine candidates (see Table 1). Interestingly, the analyses suggested that M72/AS01E induced the highest antigen-specific memory CD4+ cell response among the candidates. Unfortunately, the study did not include results from whole cell or live vaccine candidates, which are known to induce a more diverse and broader repertoire of immune responses.

Overall, the recent positive clinical trial data referred to above represent a very important milestone in international efforts to develop a novel efficacious TB vaccine. These successes illustrate that TB vaccine research is on the right track and will be able to deliver a much-needed improved vaccine strategy that is so critical for controlling the global TB epidemic. It is critical that the field moves forward with urgency towards phase III licensure trials so that an impact on the epidemic can be achieved swiftly. These findings therefore signal the end of the ‘post-MVA85A period’ of fundamental doubts about both the usefulness of the TB vaccine research strategy and the TB animal models in vaccine discovery83. The M72/ASO1E vaccine contains only two antigens, and the next generation of vaccines may be improved by adding more antigens to increase immune coverage and avoid the risk of escape. The efficacy signal observed with M72/ASO1E will likely also establish the M72/ASO1E-induced protection as a minimum benchmark in preclinical animal models. As discussed above, many subunit vaccine candidates appear to induce a response that is typically characterized by early differentiated CD4+ TCM and TEM cells, whereas it seems that both viral and live mycobacterial vectors promote a more differentiated CD4+ TEFF cell response27,52,54,82,84,85. It will therefore be important to agree on a standard set of parameters that would allow an accurate comparison between studies and vaccines to determine whether this is a reproducible pattern in clinical trials. Recent results of preclinical studies using a recombinant human cytomegalovirus encoding several Mtb T cell antigens have shown impressive protection in an NHP model, where prophylactic vaccination prevented infection in one-third of experimentally infected rhesus macaques86. Because cytomegalovirus vectored vaccines establish a persistent lifelong infection and induce a high level of antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses, these findings suggest that, in addition to T cell differentiation as discussed above, the sheer size of the pool of Mtb-specific CD4+ T cells has an impact on protection. This is also supported by the M72/ASO1E trial results, as this vaccine promotes a high frequency of antigen-specific T cells. However, more is not always better, and there is a risk of less protection and insufficient immune memory or even of inflicting immunopathology with vaccines that induce very strong T cell responses, particularly when used in the postexposure setting in individuals with LTBI. With an efficacy signal in young adolescents and/or adults from both BCG revaccination and subunit vaccine studies, it is intriguing to speculate whether the combination of both, administered sequentially or simultaneously87, may pave the way for a vaccination strategy that protects both uninfected and infected people while providing the possibility of a synergistic effect for inducing more diverse and broader-ranging immune responses. If an additive effect can be demonstrated, the combination of BCG and subunit vaccines may represent a new strategy that elevates the efficacy signal into a range that triggers clinical implementation.

References

World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2018 (WHO, 2018).

Houben, R. M. & Dodd, P. J. The global burden of latent tuberculosis infection: a re-estimation using mathematical modelling. PLOS Med. 13, e1002152 (2016).

Behr, M. A., Edelstein, P. H. & Ramakrishnan, L. Revisiting the timetable of tuberculosis. BMJ 362, k2738 (2018).

Barry, C. E. et al. The spectrum of latent tuberculosis: rethinking the biology and intervention strategies. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7, 845–855 (2009).

Robertson, B. D. et al. Detection and treatment of subclinical tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 92, 447–452 (2012).

Pai, M. et al. Tuberculosis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2, 16076 (2016).

Drain, P. K. et al. Incipient and subclinical tuberculosis: a clinical review of early stages and progression of infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 31, e00021-18 (2018).

Scriba, T. J. et al. Sequential inflammatory processes define human progression from M. tuberculosis infection to tuberculosis disease. PLOS Pathog. 13, e1006687 (2017).

Hunter, R. L. The pathogenesis of tuberculosis: the early infiltrate of post-primary (adult pulmonary) tuberculosis: a distinct disease entity. Front. Immunol. 9, 2108 (2018).

Tameris, M. D. et al. Safety and efficacy of MVA85A, a new tuberculosis vaccine, in infants previously vaccinated with BCG: a randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet 381, 1021–1028 (2013). This paper reports the safety, immunogenicity and efficacy of the first viral vectored TB vaccine candidate, MVA85A, in infants who received BCG at birth. No protection against Mtb infection or TB disease was observed.

Nemes, E. et al. Prevention of M. tuberculosis infection with H4:IC31 vaccine or BCG revaccination. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 138–149 (2018). This paper reports the results of a phase IIb prevention of Mtb infection trial and demonstrates that BCG revaccination affords significant protection against sustained IGRA conversion in South African adolescents who received BCG at birth.

Van Der Meeren, V. D. M. et al. Phase 2b controlled trial of M72/AS01E vaccine to prevent tuberculosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 1621–1634 (2018). This phase IIb trial in IGRA-positive adults from three African countries demonstrates for the first time that a protein subunit TB vaccine candidate can protect against TB disease.

Cambier, C. J. et al. Mycobacteria manipulate macrophage recruitment through coordinated use of membrane lipids. Nature 505, 218–222 (2014).

Shafiani, S., Tucker-Heard, G., Kariyone, A., Takatsu, K. & Urdahl, K. B. Pathogen-specific regulatory T cells delay the arrival of effector T cells in the lung during early tuberculosis. J. Exp. Med. 207, 1409–1420 (2010).

Ernst, J. D. Mechanisms of M. tuberculosis immune evasion as challenges to TB vaccine design. Cell Host Microbe 24, 34–42 (2018).

Reiley, W. W. et al. ESAT-6-specific CD4 T cell responses to aerosol Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection are initiated in the mediastinal lymph nodes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 10961–10966 (2008).

Poulsen, A. Some clinical features of tuberculosis. 1. Incubation period. Acta Tuberc. Scand. 24, 311–346 (1950).

Wallgren, A. The time-table of tuberculosis. Tubercle 29, 245–251 (1948).

Khader, S. A. et al. IL-23 and IL-17 in the establishment of protective pulmonary CD4+T cell responses after vaccination and during Mycobacterium tuberculosis challenge. Nat. Immunol. 8, 369–377 (2007).

Woodworth, J. S. et al. Subunit vaccine H56/CAF01 induces a population of circulating CD4 T cells that traffic into the Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected lung. Mucosal Immunol. 10, 555–564 (2017).

Ahmed, M. et al. A novel nanoemulsion vaccine induces mucosal interleukin-17 responses and confers protection upon Mycobacterium tuberculosis challenge in mice. Vaccine 35, 4983–4989 (2017).

Dijkman, K. et al. Prevention of tuberculosis infection and disease by local BCG in repeatedly exposed rhesus macaques. Nat. Med. 25, 255–262 (2019). This paper demonstrates in an NHP model that mucosal BCG vaccination affords high-level protection against repeated, low-dose infection and identifies mucosal antigen-specific T H 1 cell and/or T H 17 cell and IgA responses as putative COP.

Nunes-Alves, C. et al. In search of a new paradigm for protective immunity to TB. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 289–299 (2014).

Sakai, S. et al. CD4 T cell-derived IFN-gamma plays a minimal role in control of pulmonary Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection and must be actively repressed by PD-1 to prevent lethal disease. PLOS Pathog. 12, e1005667 (2016).

Goldsack, L. & Kirman, J. R. Half-truths and selective memory: interferon gamma, CD4+ T cells and protective memory against tuberculosis. Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 87, 465–473 (2007).

Fletcher, H. A. et al. T cell activation is an immune correlate of risk in BCG vaccinated infants. Nat. Commun. 7, 11290 (2016). This paper investigates immunological correlates of risk of TB in infants who participated in the first phase IIb trial of the MVA85A vaccine candidate. BCG-specific IFNγ-expressing cells and Ag85A-specific IgG antibody titres correlate with low risk of progression to TB, while HLA-DR + CD4 + T cells correlate with high risk of progression to TB.

Tameris, M. et al. The candidate TB vaccine, MVA85A, induces highly durable Th1 responses. PLOS ONE 9, e87340 (2014).

Kagina, B. M. et al. Specific T cell frequency and cytokine expression profile do not correlate with protection against tuberculosis after bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccination of newborns. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 182, 1073–1079 (2010).

Sallin, M. A. et al. Host resistance to pulmonary Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection requires CD153 expression. Nat. Microbiol. 3, 1198–1205 (2018).

Billeskov, R., Vingsbo-Lundberg, C., Andersen, P. & Dietrich, J. Induction of CD8 T cells against a novel epitope in TB10.4: correlation with mycobacterial virulence and the presence of a functional region of difference-1. J. Immunol. 179, 3973–3981 (2007).

Lin, P. L. & Flynn, J. L. CD8 T cells and Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Semin. Immunopathol. 37, 239–249 (2015).

Chen, C. Y. et al. A critical role for CD8 T cells in a nonhuman primate model of tuberculosis. PLOS Pathog. 5, e1000392 (2009).

Lindenstrom, T., Aagaard, C., Christensen, D., Agger, E. M. & Andersen, P. High-frequency vaccine-induced CD8+ T cells specific for an epitope naturally processed during infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis do not confer protection. Eur. J. Immunol. 44, 1699–1709 (2014).

Yang, J. D. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells differ in their capacity to recognize infected macrophages. PLOS Pathog. 14, e1007060 (2018).

Nyendak, M. et al. Adenovirally-induced polyfunctional T cells do not necessarily recognize the infected target: lessons from a phase I trial of the AERAS-402 vaccine. Sci. Rep. 6, 36355 (2016).

Lu, L. L. et al. A functional role for antibodies in tuberculosis. Cell 167, 433–443 (2016).

Abebe, F. et al. IgA and IgG against Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv2031 discriminate between pulmonary tuberculosis patients, Mycobacterium tuberculosis-infected and non-infected individuals. PLOS ONE 13, e0190989 (2018).

Portal-Celhay, C. et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis EsxH inhibits ESCRT-dependent CD4+ T cell activation. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 16232 (2016).

Bold, T. D., Banaei, N., Wolf, A. J. & Ernst, J. D. Suboptimal activation of antigen-specific CD4+ effector cells enables persistence of M. tuberculosis in vivo. PLOS Pathog. 7, e1002063 (2011). This study demonstrates that Mtb is recognized in the first phase of infection in the mouse model by protective T cells recognizing the Ag85 antigen but that bacterial downregulation of this antigen allows bacterial persistence in the presence of antigen-specific T cells.

Srivastava, S., Grace, P. S. & Ernst, J. D. Antigen export reduces antigen presentation and limits T cell control of M. tuberculosis. Cell Host Microbe 19, 44–54 (2016).

Heimbeck, J. Incidence of tuberculosis in young adult women with special reference to employment. Br. J. Tuberculosis 32, 154–166 (1938).

Andrews, J. R. et al. Risk of progression to active tuberculosis following reinfection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 54, 784–791 (2012). This meta-analysis of 18 human studies from the pre-chemotherapeutic era suggests that prior Mtb infection provides high-level protection against risk of progression to TB disease when individuals in contact with patients with TB are exposed to Mtb again.

Cadena, A. M. et al. Concurrent infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis confers robust protection against secondary infection in macaques. PLOS Pathog. 14, e1007305 (2018).

Kaushal, D. et al. Mucosal vaccination with attenuated Mycobacterium tuberculosis induces strong central memory responses and protects against tuberculosis. Nat. Commun. 6, 8533 (2015).

Mpande, C. A. M. et al. Functional, antigen-specific stem cell memory (TSCM) CD4+ T cells are induced by human Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Front. Immunol. 9, 324 (2018).

Boer, M. C. et al. KLRG1 and PD-1 expression are increased on T cells following tuberculosis-treatment and identify cells with different proliferative capacities in BCG-vaccinated adults. Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 97, 163–171 (2016).

Day, C. L. et al. Functional capacity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific T cell responses in humans is associated with mycobacterial load. J. Immunol. 187, 2222–2232 (2011).

Rozot, V. et al. Combined use of Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific CD4 and CD8 T cell responses is a powerful diagnostic tool of active tuberculosis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 60, 432–437 (2015).

Nikitina, I. Y. et al. Th1, Th17, and Th1Th17 lymphocytes during tuberculosis: Th1 lymphocytes predominate and appear as low-differentiated CXCR3+CCR6+ cells in the blood and highly differentiated CXCR3+/−CCR6- cells in the lungs. J. Immunol. 200, 2090–2103 (2018).

Jayaraman, P. et al. TIM3 mediates T cell exhaustion during Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection. PLOS Pathog. 12, e1005490 (2016).

Reiley, W. W. et al. Distinct functions of antigen-specific CD4 T cells during murine Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 19408–19413 (2010).

Lindenstrom, T., Knudsen, N. P., Agger, E. M. & Andersen, P. Control of chronic Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection by CD4 KLRG1- IL-2-secreting central memory cells. J. Immunol. 190, 6311–6319 (2013). This study demonstrates the importance of vaccine-promoted T CM cells in the long-term maintenance of protection against chronic Mtb infection in the mouse model.

Orme, I. M. The Achilles heel of BCG. Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 90, 329–332 (2010).

Lindenstrom, T. et al. T cells primed by live mycobacteria versus a tuberculosis subunit vaccine exhibit distinct functional properties. EBioMedicine 27, 27–39 (2018). This study demonstrates that live mycobacteria (either Mtb or BCG) prime T cells in mice that are more differentiated than T cells induced in response to subunit vaccines and that this difference has profound influence on the migration of the Mtb-specific T cells to the lung parenchyma.

Sakai, S. et al. Cutting edge: control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection by a subset of lung parenchyma-homing CD4 T cells. J. Immunol. 192, 2965–2969 (2014). This paper is the first to demonstrate that, in the mouse model, less differentiated KLRG1 – CXCR3 + T CM cell-like cells readily migrate into the Mtb-infected lung parenchyma, in contrast to KLRG1 + CXCR3 – T EFF cells.

Torrado, E. et al. Interleukin 27R regulates CD4+ T cell phenotype and impacts protective immunity during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Exp. Med. 212, 1449–1463 (2015).

Woodworth, J. S. et al. Protective CD4 T cells targeting cryptic epitopes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis resist infection-driven terminal differentiation. J. Immunol. 192, 3247–3258 (2014).

Sallin, M. A. et al. Th1 differentiation drives the accumulation of intravascular, non-protective CD4 T cells during tuberculosis. Cell Rep. 18, 3091–3104 (2017).

Behar, S. M., Carpenter, S. M., Booty, M. G., Barber, D. L. & Jayaraman, P. Orchestration of pulmonary T cell immunity during Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection: immunity interruptus. Semin. Immunol. 26, 559–577 (2014).

Urdahl, K. B. Understanding and overcoming the barriers to T cell-mediated immunity against tuberculosis. Semin. Immunol. 26, 578–587 (2014).

Rogerson, B. J. et al. Expression levels of Mycobacterium tuberculosis antigen-encoding genes versus production levels of antigen-specific T cells during stationary level lung infection in mice. Immunology 118, 195–201 (2006).

Shi, L., North, R. & Gennaro, M. L. Effect of growth state on transcription levels of genes encoding major secreted antigens of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the mouse lung. Infect. Immun. 72, 2420–2424 (2004).

Moguche, A. O. et al. Antigen availability shapes T cell differentiation and function during tuberculosis. Cell Host Microbe 21, 695–706 (2017). This paper demonstrates that the Mtb antigens Ag85B and ESAT6 are differentially expressed during infection in mice and humans. CD4 + T cells that recognize these antigens exhibit distinct patterns of differentiation, and their capacities to mediate protective immunity are restricted in different ways.

Coscolla, M. et al. M. tuberculosis T cell epitope analysis reveals paucity of antigenic variation and identifies rare variable TB antigens. Cell Host Microbe 18, 538–548 (2015).

Woodworth, J. S. & Andersen, P. Reprogramming the T cell response to tuberculosis. Trends Immunol. 37, 81–83 (2016).

Comas, I. et al. Human T cell epitopes of Mycobacterium tuberculosis are evolutionarily hyperconserved. Nat. Genet. 42, 498–503 (2010).

Harari, A., Vallelian, F. & Pantaleo, G. Phenotypic heterogeneity of antigen-specific CD4 T cells under different conditions of antigen persistence and antigen load. Eur. J. Immunol. 34, 3525–3533 (2004).

Vordermeier, H. M. et al. Correlation of ESAT-6-specific gamma interferon production with pathology in cattle following Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccination against experimental bovine tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 70, 3026–3032 (2002).

Langermans, J. A. et al. Divergent effect of bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccination on Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in highly related macaque species: implications for primate models in tuberculosis vaccine research. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 11497–11502 (2001).

Barber, D. L., Mayer-Barber, K. D., Feng, C. G., Sharpe, A. H. & Sher, A. CD4 T cells promote rather than control tuberculosis in the absence of PD-1-mediated inhibition. J. Immunol. 186, 1598–1607 (2011).

Cruz, A. et al. Pathological role of interleukin 17 in mice subjected to repeated BCG vaccination after infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Exp. Med. 207, 1609–1616 (2010).

Billeskov, R. et al. High antigen dose is detrimental to post-exposure vaccine protection against tuberculosis. Front. Immunol. 8, 1973 (2018).

World Health Organization. WHO statement on BCG revaccination for the prevention of tuberculosis. Bull. World Health Organ. 73, 805–806 (1995).

Rodrigues, L. C. et al. Effect of BCG revaccination on incidence of tuberculosis in school-aged children in Brazil: the BCG-REVAC cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 366, 1290–1295 (2005).

Karonga Prevention Trial Group. Randomised controlled trial of single BCG, repeated BCG, or combined BCG and killed Mycobacterium leprae vaccine for prevention of leprosy and tuberculosis in Malawi. Lancet 348, 17–24 (1996).

Barreto, M. L. et al. Causes of variation in BCG vaccine efficacy: examining evidence from the BCG REVAC cluster randomized trial to explore the masking and the blocking hypotheses. Vaccine 32, 3759–3764 (2014). This analysis of the BCG REVAC cluster-randomized trial in Brazil reports some protection against TB in Salvador and no protection in Manaus and shows that variability in BCG efficacy was high when BCG was administered to children of school age but absent when BCG was administered at birth. The study suggests that prior immunological sensitization blocks, rather than masks, the protective effects of BCG.

Nemes, E. et al. Optimization and interpretation of serial QuantiFERON testing to measure acquisition of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 196, 638–648 (2017).

Dye, C. Making wider use of the world’s most widely used vaccine: bacille Calmette-Guerin revaccination reconsidered. J. R. Soc. Interface 10, 20130365 (2013). This paper discusses the considerations around strategies for utilizing BCG revaccination to achieve higher levels of protection against TB in different parts of the world.

Suliman, S. et al. Dose optimization of H56:IC31 vaccine for TB endemic populations: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-selection trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 199, 220–231 (2018).

Day, C. L. et al. Induction and regulation of T cell immunity by the novel tuberculosis vaccine M72/AS01 in South African adults. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 188, 492–502 (2013).

Penn-Nicholson, A. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of candidate vaccine M72/AS01E in adolescents in a TB endemic setting. Vaccine 33, 4025–4034 (2015).

Rodo, M. J. et al. A comparison of antigen-specific T cell responses induced by six novel tuberculosis vaccine candidates. PLOS Pathog. 15, e1007643 (2019).

Macleod, M. Learning lessons from MVA85A, a failed booster vaccine for BCG. BMJ 360, k66 (2018).

Billeskov, R., Christensen, J. P., Aagaard, C., Andersen, P. & Dietrich, J. Comparing adjuvanted H28 and modified vaccinia virus ankara expressing H28 in a mouse and a non-human primate tuberculosis model. PLOS ONE 8, e72185 (2013).

Leung-Theung-Long, S. et al. A novel MVA-based multiphasic vaccine for prevention or treatment of tuberculosis induces broad and multifunctional cell-mediated immunity in mice and primates. PLOS ONE 10, e0143552 (2015).

Hansen, S. G. et al. Prevention of tuberculosis in rhesus macaques by a cytomegalovirus-based vaccine. Nat. Med. 24, 130–143 (2018). This study demonstrates in NHPs that a novel, cytomegalovirus-based TB vaccine candidate provides high-level protection against Mtb infection, disease progression and disease pathology.

Dietrich, J., Billeskov, R., Doherty, T. M. & Andersen, P. Synergistic effect of bacillus Calmette Guerin and a tuberculosis subunit vaccine in cationic liposomes: increased immunogenicity and protection. J. Immunol. 178, 3721–3730 (2007).

Brosch, R. et al. Genome plasticity of BCG and impact on vaccine efficacy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 5596–5601 (2007).

Behr, M. A. et al. Comparative genomics of BCG vaccines by whole-genome DNA microarray. Science 284, 1520–1523 (1999).

Nieuwenhuizen, N. E. & Kaufmann, S. H. E. Next-generation vaccines based on bacille Calmette-Guerin. Front. Immunol. 9, 121 (2018).

Scriba, T. J. et al. Vaccination against tuberculosis with whole-cell mycobacterial vaccines. J. Infect. Dis. 214, 659–664 (2016).

Kaufmann, E. et al. BCG educates hematopoietic stem cells to generate protective innate immunity against tuberculosis. Cell 172, 176–190 (2018).

Fine, P. E. Variation in protection by BCG: implications of and for heterologous immunity. Lancet 346, 1339–1345 (1995).

Abubakar, I. et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the current evidence on the duration of protection by bacillus Calmette-Guerin vaccination against tuberculosis. Health Technol. Assess. 17, 1–372 (2013).

Aronson, N. E. et al. Long-term efficacy of BCG vaccine in American Indians and Alaska Natives: a 60-year follow-up study. JAMA 291, 2086–2091 (2004).

Nguipdop-Djomo, P., Heldal, E., Rodrigues, L. C., Abubakar, I. & Mangtani, P. Duration of BCG protection against tuberculosis and change in effectiveness with time since vaccination in Norway: a retrospective population-based cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 16, 219–226 (2016).

Palmer, C. E. & Long, M. W. Effects of infection with atypical mycobacteria on BCG vaccination and tuberculosis. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 94, 553–568 (1966).

Mangtani, P. et al. Protection by BCG vaccine against tuberculosis: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Infect. Dis. 58, 470–480 (2014).

Andersen, P. & Doherty, T. M. The success and failure of BCG - implications for a novel tuberculosis vaccine. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 656–662 (2005).

Hoefsloot, W. et al. The geographic diversity of nontuberculous mycobacteria isolated from pulmonary samples: an NTM-NET collaborative study. Eur. Respir. J. 42, 1604–1613 (2013).

von Reyn, C. F. BCG, latitude, and environmental mycobacteria. Clin. Infect. Dis. 59, 607–608 (2014).

Qin, L., Gilbert, P. B., Corey, L., McElrath, M. J. & Self, S. G. A framework for assessing immunological correlates of protection in vaccine trials. J. Infect. Dis. 196, 1304–1312 (2007).

Jasenosky, L. D., Scriba, T. J., Hanekom, W. A. & Goldfeld, A. E. T cells and adaptive immunity to Mycobacterium tuberculosis in humans. Immunol. Rev. 264, 74–87 (2015).

Voss, G. et al. Progress and challenges in TB vaccine development. F1000Res. 7, 199 (2018).

Nieuwenhuizen, N. E. et al. The recombinant bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccine VPM1002: ready for clinical efficacy testing. Front. Immunol. 8, 1147 (2017).

Loxton, A. G. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the recombinant Mycobacterium bovis BCG vaccine VPM1002 in HIV-unexposed newborn infants in South Africa. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 24, e00439-16 (2017).

Arbues, A. et al. Construction, characterization and preclinical evaluation of MTBVAC, the first live-attenuated M. tuberculosis-based vaccine to enter clinical trials. Vaccine 31, 4867–4873 (2013).

Aguilo, N. et al. Reactogenicity to major tuberculosis antigens absent in BCG is linked to improved protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Commun. 8, 16085 (2017).

Spertini, F. et al. Safety of human immunisation with a live-attenuated Mycobacterium tuberculosis vaccine: a randomised, double-blind, controlled phase I trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 3, 953–962 (2015).

Cardona, P. J. RUTI: a new chance to shorten the treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. Tuberculosis (Edinb.) 86, 273–289 (2006).

Nell, A. S. et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of the novel antituberculous vaccine RUTI: randomized, placebo-controlled phase II clinical trial in patients with latent tuberculosis infection. PLOS ONE 9, e89612 (2014).

Lahey, T. et al. Immunogenicity of a protective whole cell mycobacterial vaccine in HIV-infected adults: a phase III study in Tanzania. Vaccine 28, 7652–7658 (2010).

von Reyn, C. F. et al. Prevention of tuberculosis in bacille Calmette-Guerin-primed, HIV-infected adults boosted with an inactivated whole-cell mycobacterial vaccine. AIDS 24, 675–685 (2010).

Sharma, S. K. et al. Efficacy and safety of Mycobacterium indicus pranii as an adjunct therapy in category II pulmonary tuberculosis in a randomized trial. Sci. Rep. 7, 3354 (2017).

Mayosi, B. M. et al. Prednisolone and Mycobacterium indicus pranii in tuberculous pericarditis. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 1121–1130 (2014).

Leroux-Roels, I. et al. Improved CD4+ T cell responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis in PPD-negative adults by M72/AS01 as compared to the M72/AS02 and Mtb72F/AS02 tuberculosis candidate vaccine formulations: a randomized trial. Vaccine 31, 2196–2206 (2013).

Dietrich, J. et al. Exchanging ESAT6 with TB10.4 in an Ag85B fusion molecule-based tuberculosis subunit vaccine: efficient protection and ESAT6-based sensitive monitoring of vaccine efficacy. J. Immunol. 174, 6332–6339 (2005).

Szabo, A. et al. The two-component adjuvant IC31® boosts type I interferon production of human monocyte-derived dendritic cells via ligation of endosomal TLRs. PLOS ONE 8, e55264 (2013).

Aagaard, C. et al. A multistage tuberculosis vaccine that confers efficient protection before and after exposure. Nat. Med. 17, 189–194 (2011).

Hoang, T. et al. ESAT-6 (EsxA) and TB10.4 (EsxH) based vaccines for pre- and post-exposure tuberculosis vaccination. PLOS ONE 8, e80579 (2013).

Lin, P. L. et al. The multistage vaccine H56 boosts the effects of BCG to protect cynomolgus macaques against active tuberculosis and reactivation of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Clin. Invest. 122, 303–314 (2012).

Luabeya, A. K. et al. First-in-human trial of the post-exposure tuberculosis vaccine H56:IC31 in Mycobacterium tuberculosis infected and non-infected healthy adults. Vaccine 33, 4130–4140 (2015).

Coler, R. N. et al. The TLR-4 agonist adjuvant, GLA-SE, improves magnitude and quality of immune responses elicited by the ID93 tuberculosis vaccine: first-in-human trial. NPJ Vaccines 3, 34 (2018).

Penn-Nicholson, A. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the novel tuberculosis vaccine ID93 + GLA-SE in BCG-vaccinated healthy adults in South Africa: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 1 trial. Lancet Respir. Med. 6, 287–298 (2018).

Satti, I. et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a candidate tuberculosis vaccine MVA85A delivered by aerosol in BCG-vaccinated healthy adults: a phase 1, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 14, 939–946 (2014).

Scriba, T. J. et al. Dose-finding study of the novel tuberculosis vaccine, MVA85A, in healthy BCG-vaccinated infants. J. Infect. Dis. 203, 1832–1843 (2011).

Jeyanathan, M. et al. Induction of an immune-protective T-cell repertoire with diverse genetic coverage by a novel viral-vectored tuberculosis vaccine in humans. J. Infect. Dis. 214, 1996–2005 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank P. Højlund for expert secretarial assistance, K. Korsholm for the graphical layout and R. Mortensen and J. Woodworth for valuable discussions and input on the content of the paper.

Reviewer information

Nature Reviews Immunology thanks P.-J. Cardona and other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors contributed equally to all aspects of the article.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

T.J.S. declares no competing interests. P.A. is a named co-inventor on patents covering the H56:IC31 tuberculosis vaccine. The patents are assigned to the Statens Serum Institute, a not for profit organization under the Danish Ministry of Health.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Glossary

- Incipient TB

-

A state of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in which the host is likely to progress to active tuberculosis (TB) disease but has not yet manifested clinical symptoms, radiographic abnormalities or microbiological evidence of active disease. Can be detected using transcriptomic or proteomic biomarkers of inflammation.

- Subclinical TB

-

A state of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in which the host has radiographic abnormalities or microbiological evidence of active tuberculosis (TB) disease but has not yet manifested clinical symptoms of active disease.

- Priming vaccines

-

Vaccines that mediate sensitization or stimulation of an immune response with antigen for the first time; that is, the vaccines prime the immune response.

- Booster vaccines

-

Vaccines that are typically given after an earlier priming vaccine and further stimulate an immune response that already exists to an antigen to increase the response magnitude or modulate the function of the response; that is, the vaccines boost the pre-existing immune response.

- Correlates of protection

-

(COP). A measurable feature, often a functional characteristic of an immune response, that associates with protection against becoming infected and/or developing disease.

- ELISpot assay

-

(Enzyme-linked immunosorbent spot assay). A type of immune assay that quantifies the frequency of protein-secreting single cells on the basis of enzyme-linked detection of protein spots on immune-absorbent membranes.

- Inducible bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue

-

A tertiary lymphoid structure that consists of lymphoid follicles in the lungs or bronchus and that is a site for priming immune responses.

- Reactivation TB

-

Also known as post-primary tuberculosis (TB) or secondary TB; TB that typically occurs months to years after the initial infection and is associated with distinct disease manifestation compared to primary TB. Reactivation frequently occurs in the setting of weakened immunity and usually involves the lung apex.

- Cavitation

-

The formation of a cavity in the centre of a tuberculosis (TB) nodule or area of consolidation, usually in the upper lung or apex. Cavities may be detected by chest radiography or computed tomography and are a characteristic feature of post-primary or adult type TB.

- Chemotherapy for active TB

-

Drug-sensitive tuberculosis (TB) disease is typically treated with a 4-drug regimen of rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol for 2 months (the intensive phase of treatment), followed by isoniazid and rifampicin for 4 months (the continuation phase).

- IFNγ release assay

-

(IGRA). A test for infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) that measures IFNγ release by T cells after stimulation of blood or peripheral blood mononuclear cells with Mtb-specific peptides. IGRA conversion is an efficacy outcome in clinical trials that test prevention of Mtb infection, defined as conversion to a positive test without reversion to negative status in the next 2 consecutive IGRA tests, 3 months apart (that is, 3 consecutive positive IGRA results).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Andersen, P., Scriba, T.J. Moving tuberculosis vaccines from theory to practice. Nat Rev Immunol 19, 550–562 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-019-0174-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-019-0174-z

This article is cited by

-

Identification of differentially recognized T cell epitopes in the spectrum of tuberculosis infection

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Intranasal multivalent adenoviral-vectored vaccine protects against replicating and dormant M.tb in conventional and humanized mice

npj Vaccines (2023)

-

Key advances in vaccine development for tuberculosis—success and challenges

npj Vaccines (2023)

-

T cell receptor repertoires associated with control and disease progression following Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection

Nature Medicine (2023)

-

A Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific subunit vaccine that provides synergistic immunity upon co-administration with Bacillus Calmette-Guérin

Nature Communications (2021)