Abstract

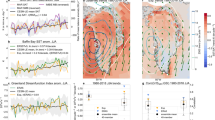

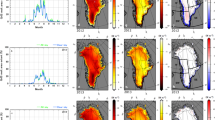

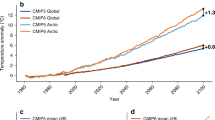

Recently, the Greenland Ice Sheet (GrIS) has become the main source of barystatic sea-level rise1,2. The increase in the GrIS melt is linked to anticyclonic circulation anomalies, a reduction in cloud cover and enhanced warm-air advection3,4,5,6,7. The Climate Model Intercomparison Project fifth phase (CMIP5) General Circulation Models (GCMs) do not capture recent circulation dynamics; therefore, regional climate models (RCMs) driven by GCMs still show significant uncertainties in future GrIS sea-level contribution, even within one emission scenario5,8,9,10. Here, we use the RCM Modèle Atmosphèrique Règional to show that the modelled cloud water phase is the main source of disagreement among future GrIS melt projections. We show that, in the current climate, anticyclonic circulation results in more melting than under a neutral-circulation regime. However, we find that the GrIS longwave cloud radiative effect is extremely sensitive to the modelled cloud liquid-water path, which explains melt anomalies of +378 Gt yr–1 (+1.04 mm yr–1 global sea level equivalent) in a +2 °C-warmer climate with a neutral-circulation regime (equivalent to 21% more melt than under anticyclonic circulation). The discrepancies between modelled cloud properties within a high-emission scenario introduce larger uncertainties in projected melt volumes than the difference in melt between low- and high-emission scenarios11.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The monthly means from 1980 to 2100 of all three MAR RCP 8.5 simulations used in this study are available via ftp://ftp.climato.be/fettweis/MARv3.9/Greenland/. If daily outputs are required, they can be requested from X.F. (xavier.fettweis@uliege.be) and S.H.

Code availability

All the code used for the analysis in this study is available upon request from the corresponding author.

References

Van Den Broeke, M. R. et al. On the recent contribution of the Greenland ice sheet to sea level change. Cryosphere 10, 1933–1946 (2016).

van den Broeke, M. et al. Greenland ice sheet surface mass loss: recent developments in observation and modeling. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 3, 345–356 (2017).

Box, J. E. et al. Greenland ice sheet albedo feedback: thermodynamics and atmospheric drivers. Cryosphere 6, 821–839 (2012).

Hofer, S., Tedstone, A. J., Fettweis, X. & Bamber, J. L. Decreasing cloud cover drives the recent mass loss on the Greenland Ice Sheet. Sci. Adv. 3, e1700584 (2017).

Delhasse, A., Fettweis, X., Kittel, C., Amory, C. & Agosta, C. Brief communication: impact of the recent atmospheric circulation change in summer on the future surface mass balance of the Greenland Ice Sheet. Cryosphere 12, 3409–3418 (2018).

Fettweis, X. et al. Reconstructions of the 1900–2015 Greenland ice sheet surface mass balance using the regional climate MAR model. Cryosphere 11, 1015–1033 (2017).

Hanna, E., Cropper, T. E., Hall, J. & Cappelen, J. Greenland blocking index 1851–2015: a regional climate change signal. Int. J. Climatol. 4861, 4847–4861 (2016).

Taylor, K. E., Stouffer, R. J. & Meehl, G. A. An Overview of CMIP5 and the experiment design. B. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 93, 485–498 (2012).

Knutti, R. & Sedláček, J. Robustness and uncertainties in the new CMIP5 climate model projections. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 369–373 (2013).

Hanna, E., Fettweis, X. & Hall, R. J. Brief communication: recent changes in summer Greenland blocking captured by none of the CMIP5 models. Cryosphere 12, 3287–3292 (2018).

Church, J. et al. in Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis (eds Stocker, T. F. et al.) 1137–1216 (IPCC, Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013).

Bintanja, R. & Van Den Broeke, M. R. The influence of clouds on the radiation budget of ice and snow surfaces in Antarctica and Greenland in summer. Int. J. Climatol. 16, 1281–1296 (1996).

Warren, S. G. Optical properties of snow. Rev. Geophys. 20, 67 (1982).

Shupe, M. D. & Intrieri, J. M. Cloud radiative forcing of the Arctic surface: the influence of cloud properties, surface albedo, and solar zenith angle. J. Climate 17, 616–628 (2004).

Van Tricht, K. et al. Clouds enhance Greenland ice sheet meltwater runoff. Nat. Commun. 7, 10266 (2016).

Bennartz, R. et al. July 2012 Greenland melt extent enhanced by low-level liquid clouds. Nature 496, 83–86 (2013).

Bony, S. et al. CFMIP: Towards a better evaluation and understanding of clouds and cloud feedbacks in CMIP5 models. Clivar Exch. 56, 20–22 (2011).

Tsay, S. et al. Radiative energy budget in the cloudy and hazy Arctic. J. Atmos. Sci. 46 , 1002–1018 (1989).

Fettweis, X. et al. Estimating the Greenland ice sheet surface mass balance contribution to future sea level rise using the regional atmospheric climate model MAR. Cryosphere 7, 469–489 (2013).

Fettweis, X., Tedesco, M., Van Den Broeke, M. & Ettema, J. Melting trends over the Greenland ice sheet (1958–2009) from spaceborne microwave data and regional climate models. Cryosphere 5, 359–375 (2011).

IPCC Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis (eds. Stocker, T. F. et al.) Annex iii: Glossary (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2013).

Franco, B., Fettweis, X. & Erpicum, M. Future projections of the Greenland ice sheet energy balance driving the surface melt. Cryosphere 7, 1–18 (2013).

Tedesco, M. et al. The darkening of the Greenland ice sheet: trends, drivers, and projections (1981–2100). Cryosphere 10, 477–496 (2016).

Tedstone, A. J. et al. Dark ice dynamics of the south-west Greenland Ice Sheet. Cryosphere 11, 2491–2506 (2017).

Alexander, P. M. et al. Assessing spatio-temporal variability and trends in modelled and measured Greenland Ice Sheet albedo (2000–2013). Cryosphere 8, 2293–2312 (2014).

Cook, J. M. et al. Quantifying bioalbedo: a new physically based model and discussions of empirical methods for characterising biological influence on ice and snow albedo. Cryosphere 11, 2611–2632 (2017).

Curry, J. A. & Ebert, E. E. Annual cycle of radiation fluxes over the Arctic Ocean: sensitivity to cloud optical properties. J. Climate 5, 1267–1280 (1992).

Stroeve, J. C. et al. Trends in Arctic sea ice extent from CMIP5, CMIP3 and observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L16502 (2012).

Trenberth, K. E., Fasullo, J. T., Branstator, G. & Phillips, A. S. Seasonal aspects of the recent pause in surface warming. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 911–916 (2014).

Ding, Q. et al. Tropical forcing of the recent rapid Arctic warming in northeastern Canada and Greenland. Nature 509, 209–12 (2014).

Miller, N. B. et al. Cloud radiative forcing at Summit Greenland. J. Clim. 28, 6267–6280 (2015).

Miller, N. B. et al. Surface energy budget responses to radiative forcing at Summit, Greenland. Cryosphere 11, 497–516 (2017).

Dee, D. P. et al. The ERA-Interim reanalysis: configuration and performance of the data assimilation system. Q. J. Roy. Meteor. Soc. 137, 553–597 (2011).

Hanna, E. et al. Atmospheric and oceanic climate forcing of the exceptional Greenland ice sheet surface melt in summer 2012. Int. J. Climatol. 34, 1022–1037 (2014).

Fettweis, X. et al. Brief communication: important role of the mid-tropospheric atmospheric circulation in the recent surface melt increase over the Greenland ice sheet. Cryosphere 7, 241–248 (2013).

Wang, W., Zender, C. S. & van As, D. Temporal characteristics of cloud radiative effects on the Greenland ice sheet: discoveries from multiyear automatic weather station measurements. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 123, 11,348–11,361 (2018).

Wang, W., Zender, C. S., van As, D. & Miller, N. B. Spatial distribution of melt‐season cloud radiative effects over Greenland: evaluating satellite observations, reanalyses, and model simulations against in-situ measurements. J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos. 124, 57–71 (2018).

Fettweis, X. Reconstruction of the 1979–2006 Greenland ice sheet surface mass balance using the regional climate model MAR. Cryosphere 1, 21–40 (2007).

Gallee, H. & Schayes, G. Development of a three-dimensional meso-γ primitive equation model: katabatic winds simulation in the area of Terra Nova Bay, Antarctica. Mon. Weather Rev. 122, 671–685 (1994).

De Ridder, K. & Gallée, H. Land surface–induced regional climate change in Southern Israel. J. Appl. Meteorol. 37, 1470–1485 (1998).

Gallée, H., Guyomarc’h, G. & Brun, E. Impact of snow drift on the Antarctic ice sheet surface mass balance: possible sensitivity to snow-surface properties. Bound.-Lay. Meteorol. 99, 1–19 (2001).

Meyers, M. P., DeMott, P. J. & Cotton, W. R. New primary ice-nucleation parameterizations in an explicit cloud model. J. Appl. Meteorol. 31, 708–721 (1992).

Fridlind, A. M. et al. Ice properties of single‐layer stratocumulus during the mixed‐phase Arctic cloud experiment: 2. model results. J. Geophys. Res. 112, D24201 (2007).

van den Broeke, M. et al. Partitioning recent Greenland mass loss. Science 326, 984–986 (2009).

Uppala, S. M. et al. The ERA‐40 re-analysis. Quart. J. R. Meteorolog. Soc. 131, 2961–3012 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Environment Research Council (grant no. ME/M021025/1) and received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement no. 694188. This work was also supported by the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique (FNRS) and the Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek-Vlaanderen (FWO) under the EOS Project n° O0100718F. For the MAR simulations, computational resources were provided by the Consortium des Equipements de Calcul Intensif, funded by the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique de Belgique (F.R.S.-FNRS) under grant no. 2.5020.11, and the Tier-1 supercomputer (Zenobel) of the Fèdèration Wallonie-Buxelles, and infrastructure was funded by the Walloon Region under grant agreement no. 1117545. X.F. is a research associate of the F.R.S.-FNRS. S.H. would like to thank M. McCrystall for valuable discussions on the topic.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.H. analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. S.H., J.B. and A.T. designed the study and methods. J.B. and A.T. supervised the project. X.F. developed and provided the daily climate model outputs as well as additional analyses. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information: Nature Climate Change thanks Ruth Mottram, Matthew Shupe and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, and Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hofer, S., Tedstone, A.J., Fettweis, X. et al. Cloud microphysics and circulation anomalies control differences in future Greenland melt. Nat. Clim. Chang. 9, 523–528 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-019-0507-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-019-0507-8

This article is cited by

-

Firn on ice sheets

Nature Reviews Earth & Environment (2024)

-

Discrepancies between observations and climate models of large-scale wind-driven Greenland melt influence sea-level rise projections

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Decreasing surface albedo signifies a growing importance of clouds for Greenland Ice Sheet meltwater production

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Summertime atmosphere–sea ice coupling in the Arctic simulated by CMIP5/6 models: Importance of large-scale circulation

Climate Dynamics (2021)

-

Greater Greenland Ice Sheet contribution to global sea level rise in CMIP6

Nature Communications (2020)