Abstract

External accretion events such as a galaxy merger or the accretion of gas from the immediate environment of a galaxy can create a large misalignment between the gas and the stellar kinematics. Numerical simulations have suggested that misaligned structures may promote the inflow of gas to the nucleus of the galaxy and the accretion of gas by the central supermassive black hole. We show for the first time that galaxies with a strong misalignment between the ionized gas and stellar kinematic angles have a higher observed fraction of active black holes than galaxies with aligned rotation of gas and stars. The increase in black hole activity suggests that the process of formation and/or the presence of misaligned structures are connected with the fuelling of active supermassive black holes.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$29.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data used in this study are available in the AAO Data Central repository (https://docs.datacentral.org.au/sami/). Additional data can accessed via a persistent repository at https://erda.ku.dk/archives/dcf9b1543592f8fbd824cf1eeb733b4e/published-archive.html. The following lists the availability of the catalogues used in the section ‘Cross matching with AGN catalogues’: the Second ROSAT All-Sky Survey (http://vizier.u-strasbg.fr/viz-bin/VizieR?-source=J/A+A/588/A103); the Swift/Burst Alert Telescope (BAT)AT 70-month AGN X-ray catalogue (http://vizier.u-strasbg.fr/viz-bin/VizieR?-source=J/ApJS/233/17); the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) AGN catalogue (90% confidence level) based on the AllWISE catalogue (http://vizier.u-strasbg.fr/viz-bin/VizieR?-source=J/ApJS/234/23); the catalogue of ref. 71 (http://vizier.u-strasbg.fr/viz-bin/VizieR?-source=J/ApJ/751/52) and the radio-loud AGN catalogue of ref. 72 (http://vizier.u-strasbg.fr/viz-bin/VizieR?-source=J/MNRAS/421/1569).

References

Zwicky, F. Multiple Galaxies. In Ergebnisse der exakten Naturwissenschaften Vol. 29 344–385 (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1956).

Haynes, M. P., Giovanelli, R. & Chincarini, G. L. The influence of environment on the H i content of galaxies. Annu. Rev. Astron. Astrophys. 22, 445–470 (1984).

Binney, J. & Tremaine, S. Galactic Dynamics 2nd edn (Princeton Univ. Press, 2008).

Bertola, F., Buson, L. M. & Zeilinger, W. W. The external origin of the gas in S0 galaxies. Astrophys. J. Lett. 401, L79–L81 (1992).

Sancisi, R., Fraternali, F., Oosterloo, T. & van der Hulst, T. Cold gas accretion in galaxies. Astron. Astrophys. Rev. 15, 189–223 (2008).

Kannappan, S. J. & Fabricant, D. G. A broad search for counterrotating gas and stars: evidence for mergers and accretion. Astron. J. 121, 140–147 (2001).

Davies, R. I. et al. Fueling active galactic nuclei. II. Spatially resolved molecular inflows and outflows. Astrophys. J. 792, 101 (2014).

Raimundo, S. I. et al. Tracing the origin of the AGN fuelling reservoir in MCG-6-30-15. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 464, 4227–4246 (2017).

Davis, T. A. & Bureau, M. On the depletion and accretion time-scales of cold gas in local early-type galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 457, 272–280 (2016).

Sarzi, M. et al. The SAURON project—V. Integral-field emission-line kinematics of 48 elliptical and lenticular galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 366, 1151–1200 (2006).

García-Lorenzo, B. et al. Ionized gas kinematics of galaxies in the CALIFA survey. I. Velocity fields, kinematic parameters of the dominant component, and presence of kinematically distinct gaseous systems. Astron. Astrophys. 573, A59 (2015).

Jin, Y. et al. SDSS-IV MaNGA: properties of galaxies with kinematically decoupled stellar and gaseous components. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 463, 913–926 (2016).

Bryant, J. J. et al. The SAMI Galaxy Survey: stellar and gas misalignments and the origin of gas in nearby galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 483, 458–479 (2019).

Davis, T. A. et al. The ATLAS3D project—X. On the origin of the molecular and ionized gas in early-type galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 417, 882–899 (2011).

Pizzella, A., Corsini, E. M., Vega Beltrán, J. C. & Bertola, F. Ionized gas and stellar kinematics of seventeen nearby spiral galaxies. Astron. Astrophys. 424, 447–454 (2004).

Starkenburg, T. K. et al. On the origin of star–gas counterrotation in low-mass galaxies. Astrophys. J. 878, 143 (2019).

Raimundo, S. I. et al. The black hole and central stellar population of MCG-6-30-15. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 431, 2294–2306 (2013).

Gnilka, C. L. et al. Gemini near-infrared field spectrograph observations of the Seyfert 2 galaxy Mrk 3: feeding and feedback on galactic and nuclear scales. Astrophys. J. 893, 80 (2020).

Raimundo, S. I. External gas accretion provides a fresh gas supply to the active S0 galaxy NGC 5077. Astron. Astrophys. 650, A34 (2021).

Shlosman, I., Begelman, M. C. & Frank, J. The fuelling of active galactic nuclei. Nature 345, 679–686 (1990).

Katkov, I. Y., Sil’chenko, O. K. & Afanasiev, V. L. Decoupled gas kinematics in isolated S0 galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 438, 2798–2803 (2014).

Thakar, A. R. & Ryden, B. S. Formation of massive counterrotating disks in spiral galaxies. Astrophys. J. 461, 55–76 (1996).

van de Voort, F. et al. The creation and persistence of a misaligned gas disc in a simulated early-type galaxy. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 451, 3269–3277 (2015).

Negri, A., Ciotti, L. & Pellegrini, S. The effects of stellar dynamics on the X-ray emission of flat early-type galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 439, 823–844 (2014).

Capelo, P. R. & Dotti, M. Shocks and angular momentum flips: a different path to feeding the nuclear regions of merging galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 465, 2643–2653 (2017).

Taylor, P., Federrath, C. & Kobayashi, C. The origin of kinematically distinct cores and misaligned gas discs in galaxies from cosmological simulations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 479, 141–152 (2018).

Conselice, C. J., Mundy, C. J., Ferreira, L. & Duncan, K. A direct measurement of galaxy major and minor merger rates and stellar mass accretion histories at z < 3 using galaxy pairs in the REFINE survey. Astrophys. J., 940, 168–189, (2022).

Di Matteo, P., Combes, F., Melchior, A. L. & Semelin, B. Star formation efficiency in galaxy interactions and mergers: a statistical study. Astron. Astrophys. 468, 61–81 (2007).

Silverman, J. D. et al. The impact of galaxy interactions on active galactic nucleus activity in zCOSMOS. Astrophys. J. 743, 2 (2011).

Kaviraj, S. The importance of minor-merger-driven star formation and black hole growth in disc galaxies. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 440, 2944–2952 (2014).

Croom, S. M. et al. The SAMI Galaxy Survey: the third and final data release. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 505, 991–1016 (2021).

Baldwin, J. A., Phillips, M. M. & Terlevich, R. Classification parameters for the emission-line spectra of extragalactic objects. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 93, 5–19 (1981).

Veilleux, S. & Osterbrock, D. E. Spectral classification of emission-line galaxies. Astrophys. J. Suppl. 63, 295–310 (1987).

Green, A. W. et al. The SAMI Galaxy Survey: Data Release One with emission-line physics value-added products. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 475, 716–734 (2018).

Medling, A. M. et al. The SAMI Galaxy Survey: spatially resolving the main sequence of star formation. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 475, 5194–5214 (2018).

Elvis, M., Schreier, E. J., Tonry, J., Davis, M. & Huchra, J. P. Two optically dull galaxies with strong nuclear X-ray sources. Astrophys. J. 246, 20–27 (1981).

Cameron, E. On the estimation of confidence intervals for binomial population proportions in astronomy: the simplicity and superiority of the Bayesian approach. Publ. Astron. Soc. Aust. 28, 128–139 (2011).

Heckman, T. M. An optical and radio survey of the nuclei of bright galaxies—activity in the normal galactic nuclei. Astron. Astrophys. 87, 152–164 (1980).

Dopita, M. A. & Sutherland, R. S. Spectral signatures of fast shocks. II. Optical diagnostic diagrams. Astrophys. J. 455, 468–479 (1995).

Binette, L., Magris, C. G., Stasińska, G. & Bruzual, A. G. Photoionization in elliptical galaxies by old stars. Astron. Astrophys. 292, 13–19 (1994).

Bao, M. et al. Different formation scenarios of counter-rotating stellar disks in nearby galaxies. Astrophysical Journal Letters, 926, 13–17 (2022).

Rowan-Robinson, M. A new model for the infrared emission of quasars. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 272, 737–748 (1995).

Duckworth, C. et al. Decoupling the rotation of stars and gas—II. The link between black hole activity and simulated IFU kinematics in IllustrisTNG. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 495, 4542–4547 (2020).

Ilha, G. S. et al. The first 62 AGN observed with SDSS-IV MaNGA—III: stellar and gas kinematics. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 484, 252–268 (2019).

Dumas, G., Mundell, C. G., Emsellem, E. & Nagar, N. M. Central kiloparsec of Seyfert and inactive host galaxies: a comparison of two-dimensional stellar and gaseous kinematics. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 379, 1249–1278 (2007).

Schawinski, K., Koss, M., Berney, S. & Sartori, L. F. Active galactic nuclei flicker: an observational estimate of the duration of black hole growth phases of 105 yr. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 451, 2517–2523 (2015).

Bassett, R., Bekki, K., Cortese, L. & Couch, W. The formation of S0 galaxies with counter-rotating neutral and molecular hydrogen. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 471, 1892–1909 (2017).

Koss, M. et al. Host galaxy properties of the Swift BAT ultra hard X-ray selected active galactic nucleus. Astrophys. J. 739, 57 (2011).

Khim, D. J. et al. Star–gas misalignment in galaxies. I. The properties of galaxies from the Horizon-AGN simulation and comparisons to SAMI. Astrophys. J. 894, 106 (2020).

Croom, S. M. et al. The Sydney-AAO Multi-object Integral field spectrograph. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 421, 872–893 (2012).

Allen, J. T. et al. The SAMI Galaxy Survey: Early Data Release. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 446, 1567–1583 (2015).

van de Sande, J. et al. The SAMI Galaxy Survey: revisiting galaxy classification through high-order stellar kinematics. Astrophys. J. 835, 104 (2017).

van de Sande, J. et al. The SAMI Galaxy Survey: revising the fraction of slow rotators in IFS galaxy surveys. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 472, 1272–1285 (2017).

Cappellari, M. & Emsellem, E. Parametric recovery of line-of-sight velocity distributions from absorption-line spectra of galaxies via penalized likelihood. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 116, 138–147 (2004).

Cappellari, M. Improving the full spectrum fitting method: accurate convolution with Gauss–Hermite functions. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 466, 798–811 (2017).

Cappellari, M. & Copin, Y. Adaptive spatial binning of integral-field spectroscopic data using Voronoi tessellations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 342, 345–354 (2003).

Ho, I. T. et al. LZIFU: an emission-line fitting toolkit for integral field spectroscopy data. Astrophys. Space Sci. 361, 280 (2016).

Cortese, L. et al. The SAMI Galaxy Survey: the link between angular momentum and optical morphology. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 463, 170–184 (2016).

Krajnović, D., Cappellari, M., de Zeeuw, P. T. & Copin, Y. Kinemetry: a generalization of photometry to the higher moments of the line-of-sight velocity distribution. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 366, 787–802 (2006).

Owers, M. S. et al. The SAMI Galaxy Survey: quenching of star formation in clusters I. Transition galaxies. Astrophys. J. 873, 52 (2019).

Hampton, E. J. et al. Using an artificial neural network to classify multicomponent emission lines with integral field spectroscopy from SAMI and S7. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 470, 3395–3416 (2017).

Kewley, L. J., Groves, B., Kauffmann, G. & Heckman, T. The host galaxies and classification of active galactic nuclei. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 372, 961–976 (2006).

Xia, J., Malkan, M. A., Ross, N. R. & Ancheta, A. J. Spatially resolved spectroscopic study of nearby Seyfert galaxies: implications for a population of “missed” Seyferts at high-z. Astrophys. J. 869, 138 (2018).

Ho, L. C., Filippenko, A. V. & Sargent, W. L. W. A search for “dwarf” Seyfert nuclei. V. Demographics of nuclear activity in nearby galaxies. Astrophys. J. 487, 568–578 (1997).

Wylezalek, D. et al. SDSS-IV MaNGA: identification of active galactic nuclei in optical integral field unit surveys. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 474, 1499–1514 (2018).

Hao, L. et al. Active galactic nuclei in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. I. Sample selection. Astron. J. 129, 1783–1794 (2005).

Sexton, R. O., Matzko, W., Darden, N., Canalizo, G. & Gorjian, V. Bayesian AGN decomposition analysis for SDSS spectra: a correlation analysis of [O iii] λ5007 outflow kinematics with AGN and host galaxy properties. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 500, 2871–2895 (2021).

Boller, T. et al. Second ROSAT all-sky survey (2RXS) source catalogue. Astron. Astrophys. 588, A103 (2016).

Ricci, C. et al. BAT AGN Spectroscopic Survey. V. X-ray properties of the Swift/BAT 70-month AGN catalog. Astrophys. J. Suppl. 233, 17 (2017).

Assef, R. J. et al. The WISE AGN catalog. Astrophys. J. Suppl. 234, 23 (2018).

Edelson, R. & Malkan, M. Reliable identifications of active galactic nuclei from the WISE, 2MASS, and ROSAT all-sky surveys. Astrophys. J. 751, 52 (2012).

Best, P. N. & Heckman, T. M. On the fundamental dichotomy in the local radio-AGN population: accretion, evolution and host galaxy properties. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 421, 1569–1582 (2012).

Taylor, M. B. TOPCAT & STIL: Starlink table/VOTable processing software. In Astronomical Data Analysis Software and Systems XIV, Astronomical Society of the Pacific Conference Series Vol. 347 (eds Shopbell, P. et al.) 29–33 (Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 2005).

Ochsenbein, F., Bauer, P. & Marcout, J. The VizieR database of astronomical catalogues. Astron. Astrophys. Suppl. 143, 23–32 (2000).

Astropy Collaboration et al. Astropy: a community Python package for astronomy. Astron. Astrophys. 558, A33 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 891744 (S.I.R.). This research has been financially supported by the Independent Research Fund Denmark via grant number DFF 8021-00130 (M.V.). This paper includes data that have been provided by AAO Data Central (datacentral.org.au). The SAMI Galaxy Survey is based on observations made at the Anglo-Australian Telescope. SAMI was developed jointly by the University of Sydney and the Australian Astronomical Observatory. The SAMI input catalogue is based on data taken from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, the GAMA Survey and the VST ATLAS Survey. The SAMI Galaxy Survey is funded by the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for All-sky Astrophysics (CAASTRO), through project number CE110001020, and other participating institutions. This research has made use of the VizieR catalogue access tool, CDS (https://doi.org/10.26093/cds/vizier). The original description of the VizieR service was published in ref. 74. This research made use of Astropy (http://www.astropy.org), a community-developed core Python package for Astronomy75.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.I.R. conceived the study, carried out the analysis and wrote the paper. M.M. and M.V. wrote the paper, making an equal contribution to the paper. All authors discussed the results and their interpretation and commented on the manuscript at all stages.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Astronomy thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Kinematic position angle.

Result of the kinematic position angle (PA) determination for one of the galaxies in the sample, J145002.16+003443.6, or ID 93807 in the SAMI catalogue. Left: Map of stellar velocity with title Vstar. The best fit kinematic PA is shown by the green solid line. The value determined is PAstellar = 184.0 ± 1. 5∘ where the error corresponds to the 3σ uncertainties of the fit. Right: Map of gas velocity with title Vgas. The best fit kinematic PA is shown by the green solid line, PAgas = 4 ± 4∘. The PA orientation is measured from North (PA = 0, up in the figure) to East and is per our definition oriented from the approaching (blueshifted) to the receding (redshifted) regions of the map. The dashed black line shows the zero velocity line, which is the axis that fit_kinematic_pa uses to create the mirrored bi(anti)symmetric velocity map. The measured misalignment between the stellar and gas kinematic angles for this galaxy, ΔPA = ∣PAstellar - PAgas∣ = 180∘, corresponds to counter-rotation of gas and stars.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Fraction of AGN, LINER and star forming galaxies for cutoff angle of 30 deg.

Similar to Fig. 3 but using ΔPA = 30∘ as the cut-off angle. The fraction of AGN is 7 ± 1% in aligned galaxies and 17 ± 3% in misaligned galaxies, the fraction of LINERs is 16 ± 1% in aligned galaxies and 35 ± 4% in misaligned galaxies and the fraction of star forming galaxies is 78 ± 1% in aligned galaxies and 49 ± 4% in misaligned galaxies. The absolute numbers for each bar in the order aligned/misaligned are: top left panel 65+9 − 7, 22+5 − 4; top right panel 150+12 − 11, 46+6 − 5; bottom panel 743+12 − 13, 65+6 − 6, respectively. The error bars correspond to the 68% confidence intervals using a beta distribution quantile technique.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Fraction of galaxies with a specific excitation mechanism divided by morphology.

Fraction of galaxies with a specific excitation mechanism, as a function of the misalignment between the stellar and the gas kinematic angle (ΔPA = ∣PAstars - PAgas∣) and the galaxy morphology. The histogram bars of each colour add up to 1 across the ΔPA distribution. The top panel shows the total population, the bottom left panel shows the early type galaxies and the bottom right panel shows the late type galaxies in the sample. Each panel is colour coded as a function of the main excitation mechanism in the galaxies. The panels can be understood as, for example how galaxies with emission lines from AGN, LINERs or young stars are distributed as a function of ΔPA. Almost all the late type galaxies in the sample are aligned, while early-type galaxies show a broader distribution in terms of ΔPA. Most of the misaligned galaxies have AGN or LINER as their excitation mechanism. Excitation by star formation only, in early type galaxies tends to occur mostly in aligned ΔPA < 45∘, with a smaller secondary peak in close to counter-rotating ΔPA ~ 180∘ galaxies. The fraction of star forming early-type galaxies in the fourth bin (135∘≤ΔPA ≤180∘) is marginally higher than the fraction of star forming early-type galaxies in the second and third bins at the 68% and 95% confidence level, respectively.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Pie charts with morphology classification.

Pie charts showing the morphology classification of the sub-samples of galaxies. The top row shows the sub-sample of galaxies with an excitation classification, divided into ‘aligned’ (0∘≤ΔPA < 45∘ - top left panel) and ‘misaligned’ (45∘≤ΔPA ≤180∘ - top right panel). The bottom row shows the sub-sample of galaxies classified as AGN, divided into AGN in ‘aligned’ galaxies (bottom left panel) and AGN in ‘misaligned’ galaxies (bottom right panel). The morphological classification is divided into early-type and late-type galaxies with ‘Other’ referring to an unknown morphological classification. 75% of all misaligned galaxies are in early-type galaxies while 95% of AGN with misaligned hosts are in early-type galaxies.

Extended Data Fig. 5 Emission line diagrams.

Illustration of the emission line diagrams used in this work and the theoretical regions of62 indicated by the solid and dashed lines. The text labels refer to the fraction of spaxels that fall in each of the different regions of the diagrams. For clarity we use the same names in the figure as in the text (see Methods). The suffixes ‘SF’ stand for star-forming regions, ‘AGN’ for AGN-excitation regions, ‘comp’ for composite regions (likely a combination of excitation by young stars and AGN) and ’LINER’ for low-ionization nuclear emission-line region. The suffixes [N II], [S II] and [O I] refer to each of the corresponding BPT diagrams: [N II]/Hα, [S II]/Hα and [O I]/Hα.

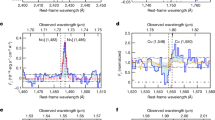

Extended Data Fig. 6 Example of emission line diagram classification.

Illustration of the line diagnostics used. Each figure shows the BPT analysis used to identify the excitation mechanisms: The three top panels show the galaxy spatial maps colour-coded by dominant excitation mechanism, purple for AGN, salmon for composite, grey for star formation and blue for LINER. Bottom panels show the BPT diagrams for each spaxel in the image, colour-coded as a function of distance from centre of the galaxy (shown as position (0,0) in the top panels). Blue symbols correspond to spaxels closest to the nucleus, red symbols to spaxels further away from the nucleus, with the range of colours calibrated for each individual galaxy. For example, the bluest point for each galaxy will be the spaxel with detected emission that is closest to its nucleus. That could be the central spaxel (distance = 0) or a spaxel that is further away from the nucleus if no emission is detected in the central spaxels. The solid and dashed lines are the classification boundaries from62. Each column refers for a specific line ratio, from left to right: [O III]/Hβ vs [N II]/Hα, [O III]/Hβ vs [S II]/Hα and [O III]/Hβ vs [O I]/Hα. The labels in the bottom row refer to the excitation classification in each region of the diagrams: AGN, LINER, SF (star-forming galaxies) or Comp (composite regions). The two figures (from top to bottom) show an example of a galaxy classified as AGN and another as LINER. An example of a star-forming galaxy is shown in Supplementary Information.

Extended Data Fig. 7 Distribution of average gas velocity dispersion.

Histograms of the distribution of average gas velocity dispersion. The y-axis shows the number of galaxies per bin. The dark-coloured histograms at the top show misaligned galaxies while the light-coloured histograms at the bottom show the aligned galaxies. The distribution for AGN are shown in the left panels while the distribution for non-AGN galaxies are shown in the right panels.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Distribution of stellar mass.

Histograms of the distribution of stellar mass in units of solar masses. The y-axis shows the number of galaxies per bin. The dark-coloured histograms at the top show misaligned galaxies while the light-coloured histograms at the bottom show the aligned galaxies. The distribution for AGN are shown in the left panels while the distribution for non-AGN galaxies are shown in the right panels.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–5 and Table 1.

Supplementary Data 1

Supplementary data for Supplementary Table 1. The file contains a .csv table.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Raimundo, S.I., Malkan, M. & Vestergaard, M. An increase in black hole activity in galaxies with kinematically misaligned gas. Nat Astron 7, 463–472 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-022-01880-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41550-022-01880-z