Abstract

We investigate the evolution of superconductivity and structure with pressure for the new superconductor FeS (T c ≈ 4.5 K), a sulfide counterpart of FeSe. A rapid suppression of T c and vanishing of superconductivity at 4.0 GPa are observed, followed by a second superconducting dome from 5.0 to 22.3 GPa with a 30% enhancement in maximum T c. An onsite tetragonal to hexagonal phase transition occurs around 7.0 GPa, followed by a broad pressure range of phase coexistence. The residual deformed tetragonal phase is considered as the source of second superconducting dome. The observation of two superconducting domes in iron-based superconductors poses great challenges for understanding their pairing mechanism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the second family of high-T c superconductor, the iron-based superconductors (IBSs) have been extensively studied in recent years.1,2,3 Among those IBSs, the tetragonal FeSe with the simplest structure has attracted much attention recently.4 Although the T c of bulk FeSe is modestly low (≈8 K),4 it can be enhanced through various methods. By applying high pressure, the T c of bulk FeSe can reach up to 36.7 K.5, 6 Through intercalation, surface K dosing, or ionic liquid gating, one can also enhance the T c to above 40 K.7,8,9,10,11 Surprisingly, the T c can be further enhanced above 60 K by growing monolayer FeSe thin film on SrTiO3 substrate,12,13,14,15,16 and even above 100 K on Nb-doped SrTiO3 substrate.17 It was believed that the enhanced electron–phonon coupling at interface is crucial in the further enhancement of T c .18, 19

The angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy studies reveal two distinct electronic band structures for these FeSe-based superconductors. The Fermi surface of the undoped bulk FeSe consists of hole pockets around Γ and electron pockets around M.15, 20,21,22,23 However, for intercalated (Li0.8Fe0.2)OHFeSe, monolayer FeSe thin film, and surface K dosed FeSe single crystal or film, the Fermi surface consists of only electron pockets, which apparently results from electron doping.7, 13,14,15,16, 24,26,27 For undoped bulk FeSe, the superconducting pairing symmetry is most likely s ± -wave with sign reversal between the hole and electron pockets,28 while for monolayer FeSe/SrTiO3, plain s-wave superconductivity was suggested by scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) study.29 Because of the large variety of FeSe-based superconductors with a wide range of T c, clarifying the superconducting mechanism will be a major step towards solving the issue of high-temperature superconductivity in IBSs.

Very recently, superconductivity with T c ≈ 4.5 K at ambient pressure was reported for FeS,30 the sister compound of FeSe. As an important Earth Science material, FeS has been extensively studied including high-pressure works,31 but superconductivity had not been observed until high-quality stoichiometric tetragonal FeS was successfully synthesized by low-temperature hydrothermal method.30 The tetragonal FeS has the same crystal structure as the tetragonal FeSe, and their electronic structures are also quite similar based on first principle calculation.32 A slight difference between them is that FeSe undergoes a phase transition to orthorhombic structure at 90 K,33 while FeS remains its tetragonal structure down to 10 K.34 Interestingly, recent thermal conductivity and specific heat measurements suggested nodal superconductivity in FeS.35, 36

Here we present in situ high-pressure electrical transport and synchrotron X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurements on tetragonal FeS single crystals. Upon applying pressure, two superconducting domes are observed. The first dome manifests a continuous decrease of T c with increasing pressure, ending ~4.0 GPa. Then a second superconducting dome emerges from 5.0 GPa and lasts to 22.3 GPa, with an over 30% increasing in T c (≈6.0 K) from the highest T c in the first dome. Comparing to the two superconducting domes of (K/Tl/Rb) x Fe2-y Se2 reported earlier,37 the superconducting pressure range is much wider, meaning the superconducting phase is much more sustainable with pressure in FeS. For its crystal structure, a hexagonal phase starts to set in at ~7.0 GPa, and there is a large coexisting pressure range of tetragonal and hexagonal phases. On the basis of the drop in R(T) curves and the structure refinement results of mixture phase region, we believe that the second superconducting dome is originated from the residual deformed tetragonal phase of FeS.

Results

Characterization at ambient pressure

The inset of Fig. 1a is a photo of as-grown FeS single crystals. Figure 1a shows a typical XRD pattern, in which only the (00l) Bragg peaks show up, indicating the crystals are well oriented along the c axis. Further XRD measurement on these crystals shows sharp single crystal diffraction spots (Fig. 1b). Flat and grain-boundary-free surface was observed with SEM (inset of Fig. 1b). Therefore, the single crystalline nature of our FeS samples is confirmed.

a Typical XRD pattern of FeS single crystals. The inset shows a photo of the as-grown FeS single crystals. b Single crystal XRD spots of an FeS sample. The inset is an SEM image of the surface. c Low-temperature dc magnetization measured in the ZFC mode at H = 10 Oe parallel to the c axis. d Temperature dependence of the resistivity ρ(T). The inset is an enlarged view of the superconducting transition. ZFC, zero-field-cooled

Figure 1c shows a typical low-temperature dc magnetization of FeS single crystals, from which the superconducting transition is at ~4.1 K. The temperature dependence of resistivity ρ(T) at ambient pressure is plotted in Fig. 1d. The absence of a resistivity anomaly in the normal state suggests no structural phase transition, which is different from FeSe single crystal.33 The low-temperature resistivity between 5 and 50 K can be well described by the Fermi liquid theory, ρ(T) = ρ 0 + AT,2 giving ρ 0 = 6.07 μΩ cm and A = 2.0 × 10−3 μΩ cm/K2. The residual resistivity ratio, RRR = ρ(298 K)/ ρ 0 = 40, is much larger than that reported previously for FeS flakes.30 The inset of Fig. 1d displays an enlarged view around the superconducting transition, from which T c onset ≈ 4.7 K and T c zero ≈ 4.3 K are obtained. T c onset is determined as the temperature where the resistivity deviates from the normal-state behavior, while T c zero as the temperature where the resistivity drops to zero. In the following discussions, we use T c onset as T c.

T c evolution under pressure

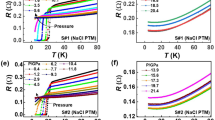

The temperature dependence of resistance up to 4.0 GPa is plotted in Fig. 2a, where the resistance is normalized to the value at 15 K for each pressure. The pressure dependence of the resistance at 15 K is shown in Fig. S1 in the Supplemental Materials. Initially, the T c is suppressed rapidly with increasing pressure, consistent with previous measurements below 2.2 GPa.38, 39 Here, we observe T c eventually disappears at 4.0 GPa. The superconductivity in this region is so sensitive to pressure that the transition broadens and the resistance does not drop to zero even under 0.86 GPa. Figure 2b, c show the normalized resistance curves above 5.0 GPa. The drop of resistance re-emerges below 4.5 K at 5.0 GPa, implying the arise of another superconducting phase. This resistance drop exists in a wide pressure range from 5.0 to 22.3 GPa, and maximum T c reaches 6 K, a 30% enhancement from the highest value in the first dome. With further increasing pressure, the resistance drop vanishes and the R(T) curve exhibits a semiconducting behavior.

a–c The normalized resistance curves of FeS single crystal under various pressures. d The superconducting transition of FeS at 19.0 GPa in various magnetic fields. The inset shows the reduced temperature (T = T c) dependence of the upper critical field H c2 (T). The solid line is a fit to the generalized Ginzburg–Landau model: H c2 (T) = H c2 (0) (1 - t 2)/(1 + t 2), where t = T/T c

To make sure the resistance drop under high pressure represents a superconducting transition, we applied magnetic field to the low-temperature resistance measurements at 19.0 GPa. As shown in Fig. 2d, the resistance drop is gradually suppressed to lower temperature with increasing field, which demonstrates that it is indeed a superconducting transition. The inset of Fig. 2d plots the reduced temperature T = T c dependence of the upper critical field H c2 . The data can be fitted to the generalized Ginzburg–Landau model: H c2 (T) = H c2 (0) (1−t 2)/(1 + t 2), where t = T/T c. According to the fit, H c2 (0) ≈ 0.81 T is obtained.

Crystal structure evolution under pressure

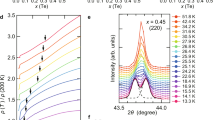

In situ synchrotron powder XRD measurements were utilized to study the structural evolution of FeS with pressure. Figure 3a displays the obtained XRD patterns under various pressures at room temperature. At the lowest pressure (1.0 GPa), the pattern can be well characterized as the tetragonal phase. From 7.2 to 9.2 GPa, a set of new peaks emerges with increasing intensity, while the intensity of the original peaks decreases. This indicates a structural transition and the coexistence of two different phases. The peaks from the low-pressure phase cannot be distinguished above 10.1 GPa, and the high-pressure phase remains stable up to 38.1 GPa.

a The in situ powder synchrotron XRD patterns of FeS under various pressures at room temperature. The characteristic peaks of two structures are marked to show the evolution with increasing pressure. b, c Net-like hexagonal structure (P-62c) and layered tetragonal structure (P4/nmm) of FeS. d–f Pressure dependence of the lattice parameters a, c, as well as unit cell volume. The red and blue solid circles represent the tetragonal and hexagonal phase, respectively. A two-phase coexisting region is highlighted from 7.2 to 9.2 GPa

On the basis of the Rietveld refinements, the low-pressure structure can be well indexed in the tetragonal space group P4/nmm, with the lattice parameters a = 3.650 Å and c = 4.940 Å at 1.0 GPa. Comparing to the ambient pressure FeS structure,30 the values of a and c decrease slightly due to the shrinkage of lattices under pressure. On the high-pressure side, the hexagonal space group P-62c is found to be the optimal structure when we refine the XRD data above 10.1 GPa. The corresponding two crystal structures are shown in Fig. 3b, c, respectively. Similar pressure-induced structural transition from a tetragonal to hexagonal phase was also observed in FeSe, with a wide pressure range for two-phase co-existence.5 The pressure dependence of the lattice parameters a, c, and unit cell volume is plotted in Fig. 3d–f, respectively. These lattice parameters show an abrupt change when the tetragonal structure transforms to the hexagonal one. The unit cell volume of the hexagonal phase is 13% smaller than that of the tetragonal phase at 7.2 GPa, which reveals the increase of the sample density, as expected.

Temperature–pressure phase diagram

We summarize our experimental results in Fig. 4. Figure 4a shows the pressure dependence of phase content around the structural transition. The hexagonal phase first appears ~7.2 GPa and its content increases rapidly with pressure. The original tetragonal phase occupies a small portion (~3%) at 9.2 GPa and is hardly distinguishable through the refinement above 10.1 GPa. The temperature–pressure (T–P) phase diagram is summarized in Fig. 4b. The superconductivity is rapidly suppressed by pressure in the first superconducting dome (SC-I), while it re-emerges in a wide pressure range from 5.0 to 22.3 GPa, manifesting as a second superconducting dome (SC-II) with a maximum T c of 6.0 K around 16.1 GPa. Upon further compression, FeS remains the hexagonal structure and behaves as a semiconductor.

Since the two-phase (tetragonal + hexagonal) coexisting region (7.2–9.2 GPa) lies inside the second superconducting dome (5.0–22.3 GPa), we try to identify which phase is responsible for SC-II. Firstly, well inside the second dome, e.g., P = 13.0 and 16.1 GPa, the sample is dominated by the hexagonal phase, but the resistance drop is only a few percent. This suggests that the SC-II should not come from the major hexagonal phase. Secondly, all the IBSs have manifested superconductivity in either tetragonal or orthorhombic phase so far.1,2,3 Thirdly, hexagonal FeS which has been extensively studied under high pressure, is in a NiAs-type structure at ambient pressure and transforms into a MnP-type structure at around 3 GPa. Upon further compression, it becomes a monoclinic structure at ~7 GPa and remains in this structure up to 40 GPa. In all the three structure, FeS shows semiconducting behavior and no superconductivity was reported.31, 40, 41 Therefore, it is very likely that the SC-II arises from the remaining tetragonal phase of FeS, which coexists with the hexagonal phase up to ~22.3 GPa. For the XRD patterns with only a few percent of tetragonal phase, it is beyond the refinement capability to distinguish it from the major hexagonal phase, thus the Rietveld refinements beyond 10.1 GPa have ignored the contribution of tetragonal phase. We notice that previous studies suggested a close relationship between the structure of Fe2 X 2 layer and T c in IBSs.42,43,44,45 Thus we perform further analysis on the detailed crystal structure of tetragonal FeS up to 9.2 GPa (see the Supplemental Materials).

Discussion

The two superconducting domes we observe here in FeS are quite different from that of its sister compound FeSe.5 For FeSe, its T–P phase diagram has only one superconducting dome with the maximum T c = 36.7 K at 8.9 GPa.5 Since sulfur atom has a smaller radius than selenium atom, FeS can be considered as FeSe under chemical pressure. In this sense, the rapid T c suppression in the first dome of FeS below 4 GPa may correspond to the high-pressure side of the superconducting dome observed in FeSe. However, so far, there is no report on the second superconducting dome in the T–P phase diagram of FeSe. The two domes in FeS are also different from the single dome observed in the T - P phase diagram of AFe2As2 (A = alkaline-earth metals) and RFeAsO (R = rare-earth metals).46

Previously, two superconducting domes in the T–P phase diagram were reported in two other IBS systems.37, 47,48,49,50,51 For (K/Tl/Rb) x Fe2-y Se2, the T c has a maximum value of 32 K at 1 GPa within the first dome, and a maximum T c of 48.7 K in the second dome between 9.8 and 13.2 GPa.37 The reason for this re-emergency of superconductivity under high pressure is still unknown. For KFe2As2, the T c exhibits a V-shaped dependence under P < 3 GPa, which was suggested as an indication of pairing symmetry change.47,48,49 Similar behavior was also observed in RbFe2As2 and CsFe2As2.50 Upon further compressing KFe2As2, a structural transition takes place from the tetragonal to collapsed tetragonal phase around 16 GPa, and a second superconducting dome with T c greatly enhanced is observed.51 However, Wang et al. later reported that the collapsed tetragonal KFe2As2 does not show superconducting behavior.52 They claim that the previously reported observation of the superconducting transition in the collapsed tetragonal phase may originate from the pressure inhomogeneity.52

Except for pressure-induced two superconducting domes, changing the carrier density can also leads to two superconducting domes in IBSs.53,54,55 In LaFeAsO1-x F x , a second superconducting dome without low-energy magnetic fluctuations was observed at 0.25 ≤ x ≤ 0.75, where the maximal T c at x opt = 0.5–0.55 is even higher than that at x ≤ 0.2.53 As for LaFeAs(O 1-x H x ), with increasing x, two superconducting domes appear: the first between 0.05 ≤ x ≤ 0.20 with T c opt = 26 K, and the second between 0.20 ≤ x ≤ 0.42 with T c opt = 36 K.54 Recent STM study showed the emergence of two disconnected superconducting domes in K dosed FeSe ultrathin films grown on SiC substrate.55 Since we did not perform Hall effect measurement on FeS single crystal under pressure, it is not clear whether there is a dramatic carrier density change with pressure in FeS.

Furthermore, two superconducting domes coming from isovalent substitution in IBSs were also reported.56,57,58 In LaFe(As1−x P x )O, the first superconducting dome appear at 0.2 ≤ x ≤ 0.4 while the second dome emerges at x > 0.7.56, 57 As for (Ca4Al2O6)Fe2(As1−x P x )2, a nodeless superconducting phase lies between 0 ≤ x ≤ 0.4 while another nodal one is around x = 1.58

Actually, a superconducting dome in T–P or T–x phase diagram has been commonly observed in unconventional superconductors, including heavy-fermion/cuprate/organic superconductors, and IBSs.59 The superconducting dome is usually related to a quantum critical point (QCP) associated with antiferromagnetism, charge-density waves, spin-density waves, nematic correlations, or orbital currents.59 For example, two distinct superconducting domes was observed in heavy-fermion superconductor CeCu2(Si1−x Ge x )2 under pressure, where the low-pressure dome is attributed to an antiferromagnetic QCP and the high-pressure dome is probably related to density fluctuations.60 For IBSs, the first dome at low carrier density or low pressure may come from a magnetic QCP.3 In the four above-mentioned IBSs (LaFeAsO1−x F x , LaFeAs(O1−x H x ), LaFe(As1−x P x )O, (Ca4Al2O6)Fe2(As1−x P x )2), the first dome is associated with an antiferromagnetic order.54, 56,57,58 In this work, however, FeS at ambient pressure is non-magnetic above T c and we note that the normal-state resistance curve of FeS with P around 4 GPa is quite flat at low temperature, which does not show a non-Fermi liquid behavior. Therefore, it is not clear whether the first dome in FeS comes from a magnetic QCP.

For the second dome in heavily doped IBSs, for instance, LaFeAs(O1−x H x ), LaFe(As1−x P x )O and (Ca4Al2O6)Fe2(As1−x P x )2, it is associated with an antiferromagnetic phase,54, 56,57,58 while in LaFeAsO1−x F x , the second superconducting dome is accompanied by a structural transition.53 Very recently, the structural and electronic properties of FeS both at ambient condition and high pressure were theoretically studied by Tresca et al.61 They claim a topological change of the Fermi surface as a function of the pressure in FeS,61 which may be the origin of the observed second superconducting dome in our work.

In summary, we demonstrate two superconducting domes in the temperature–pressure phase diagram of the newly discovered superconductor FeS by means of high-pressure resistance measurements. The in situ high-pressure XRD results reveal a phase transition from pristine tetragonal to a hexagonal structure in a broad pressure range. The superconductivity in both domes originates from tetragonal FeS phase. The observation of two superconducting domes in FeS, together with similar results reported earlier in two other IBS systems, poses great challenges for understanding the pairing mechanism of IBSs.

Methods

FeS single crystals were synthesized by de-intercalation of K from K0.8Fe1.6S2 precursor by hydrothermal method.62 XRD was carried out at room temperature using Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer (Cu K α radiation, λ = 1.5408 Å). Single crystal XRD of FeS was carried out on a Bruker SMART Apex (II) diffractometer (Mo K α radiation, λ = 0.71073 Å). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were taken on an Electron Probe Microanalyzer (Shimadzu, EPMA-1720). The dc magnetization was measured in a Superconducting Quantum Interference Device (SQUID, Quantum Design). Electrical resistivity measurement at ambient pressure was performed in 4He and 3He cryostats, by a standard four-probe technique. For resistance measurement under pressure, a non-magnetic BeCu diamond anvil cell (DAC) was used to apply high pressure. To study the structure evolution of pressurized FeS, the in situ high-pressure powder angle-dispersive XRD (AD-XRD) experiment was performed at room temperature in a Micro XRD beamline (16-BM-D), High-Pressure Collaborative Access Team (HP-CAT), Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory, using a monochromatic X-ray beam with the incident wavelength of 0.3263 Å. More experimental details can be found in the Supplemental Materials.

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Stewart, G. R. Superconductivity in iron compounds. Rev. Mod. Phys. 83, 1589 (2011).

Chen, X. H., Dai, P. C., Feng, D. L., Xiang, T. & Zhang, F.-C. Iron-based high transition temperature superconductors. Natl Sci. Rev. 1, 371–395 (2014).

Dai, P. C. Antiferromagnetic order and spin dynamics in iron-based superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 855 (2015).

Hsu, F. C. et al. Superconductivity in the PbO-type structureα-FeSe. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 14262–14264 (2008).

Medvedev, S. et al. Electronic and magnetic phase diagram of β-Fe1. 01Se with superconductivity at 36.7 K under pressure. Nat. Mater. 8, 630–633 (2009).

Mizuguchi, Y., Tomioka, F., Tsuda, S., Yamaguchi, T. & Takano, Y. Superconductivity at 27 K in tetragonal FeSe under high pressure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 152505 (2008).

Miyata, Y., Nakayama, K., Sugawara, K., Sato, T. & Takahashi, T. High-temperature superconductivity in potassium-coated multilayer FeSe thin films. Nat. Mater. 14, 775–779 (2015).

Lu, X. F. et al. Coexistence of superconductivity and antiferromagnetism in (Li0.8Fe0.2)OHFeSe. Nat. Mater. 14, 325–329 (2015).

Hanzawa, K., Sato, H., Hiramatsu, H., Kamiya, T. & Hosono, H. Field-induced superconducting transition at 31 K in insulating FeSe thin film. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 3986 (2016).

Shiogai, J., Ito, Y., Mitsuhashi, T., Nojima, T. & Tsukazaki, A. Electric-field-induced superconductivity in electrochemically etched ultrathin FeSe films on SrTiO3 and MgO. Nat. Phys. 12, 42–46 (2016).

Lei, B. et al. Evolution of high-temperature superconductivity from low-T c phase tuned by carrier concentration in FeSe thin flakes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 077002 (2016).

Wang, Q.-Y. et al. Interface-induced high-temperature superconductivity in single unit-cell FeSe films on SrTiO3. Chin. Phys. Lett. 29, 037402 (2012).

Liu, D. et al. Electronic origin of high-temperature superconductivity in single-layer FeSe superconductor. Nat. Commun. 3, 931 (2012).

He, S. L. et al. Phase diagram and electronic indication of high-temperature superconductivity at 65K in single-layer FeSe films. Nat. Mater. 12, 605–610 (2013).

Tan, S. Y. et al. Interface-induced superconductivity and strain-dependent spin density waves in FeSe/SrTiO3 thin films. Nat. Mater. 12, 634–640 (2013).

Peng, R. et al. Tuning the band structure and superconductivity in single-layer FeSe by interface engineering. Nat. Commun. 5, 5044 (2014).

Ge, J.-F. et al. Superconductivity above 100 K in single-layer FeSe films on doped SrTiO3. Nat. Mater. 14, 285–289 (2015).

Lee, J. J. et al. Interfacial mode coupling as the origin of the enhancement of T c in FeSe films on SrTiO3. Nature 515, 245–248 (2014).

Xie, Y., Cao, H. Y., Zhou, Y., Chen, S., Xiang, H. & Gong, X. G. Oxygen vacancy induced flat phonon mode at FeSe/SrTiO3 interface. . Sci. Rep. 5, 10011 (2015).

Nakayama, K. et al. Reconstruction of band structure induced by electronic nematicity in an FeSe superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 237001 (2014).

Maletz, J. et al. Unusual band renormalization in the simplest iron-based superconductor FeSe1-x. Phys. Rev. B 89, 220506(R) (2014).

Watson, M. D. et al. Emergence of the nematic electronic state in FeSe. Phys. Rev. B 91, 155106 (2015).

Zhang, P. et al. Observation of two distinct d xz /d yz band splittings in FeSe. Phys. Rev. B 91, 214503 (2015).

Wen, C. H. P. et al. Anomalous correlation effects and unique phase diagram of electron-doped FeSe revealed by photoemission spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 7, 10840 (2016).

Miyata, Y., Nakayama, K., Sugawara, K., Sato, T. & Takahashi, T. High-temperature superconductivity in potassium-coated multilayer FeSe thin films. Nat. Mater. 14, 775 (2015).

Niu, X. H. et al. Surface electronic structure and isotropic superconducting gap in (Li0.8Fe0.2) OHFeSe. Phys. Rev. B 92, 060504 (2015).

Zhao, L. et al. Common electronic origin of superconductivity in (Li,Fe)OHFeSe bulk superconductor and single-layer FeSe/SrTiO3 films. Nat. Commun. 7, 10608 (2016).

Hanaguri, T. et al. Unconventional s-wave superconductivity in Fe(Se,Te). Science 328, 474–476 (2010).

Fan, Q. et al. Plain s-wave superconductivity in single-layer FeSe on SrTiO3 probed by scanning tunneling microscopy. Nat. Phys. 11, 946–952 (2015).

Lai, X. et al. Observation of superconductivity in tetragonal FeS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 10148–10151 (2015).

Ono, S. et al. High-pressure phase transformations of FeS: novel phases at conditions of planetary cores. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 272, 481–487 (2008).

Zhang, L., Singh, D. J. & Du, M.-H. Density functional study of FeS, FeSe, and FeTe: Electronic structure, magnetism, phonons, and superconductivity. Phys. Rev. B 78, 134514 (2008).

McQueen, T. M. et al. Extreme sensitivity of superconductivity to stoichiometry in Fe1+δSe. Phys. Rev. B 79, 014522 (2009).

Pachmayr, U., Fehn, N. & Johrendt, D. Structural transition and superconductivity in hydrothermally synthesized FeX (X=S, Se). Chem. Commun. 52, 194–197 (2016).

Ying, T. P. et al. Nodal superconductivity in FeS: evidence from quasiparticle heat transport. Phys. Rev. B 94, 100504(R) (2016).

Xing, J. et al. Nodal superconducting gap in tetragonal FeS. Phys. Rev. B 93, 104520 (2016).

Sun, L. et al. Re-emerging superconductivity at 48 kelvin in iron chalcogenides. Nature 483, 67–69 (2012).

Borg, C. K. et al. Strong anisotropy in nearly ideal-tetrahedral superconducting FeS single crystals. Phys. Rev. B 93, 094522 (2016).

Holenstein, S. et al. Coexistence of low moment magnetism and superconductivity in tetragonal FeS and suppression of T c under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 93, 140506 (2016).

Gosselin, J. R., Townsend, M. G. & Tremblay, R. J. Electric anomalies at the phase transition in FeS. Solid State Commun. 19, 799–803 (1976).

Takele, S. & Hearne, G. R. Electrical transport, magnetism, and spin-state configurations of high-pressure phases of FeS. Phys. Rev. B 60, 4401 (1999).

Lee, C.-H. et al. Effect of structural parameters on superconductivity in fluorine-free LnFeAsO1-y(Ln=La, Nd). J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 77, 083704 (2008).

Horigane, K., Hiraka, H. & Ohoyama, K. Relationship between structure and superconductivity in FeSe1-xTex. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 78, 074718 (2009).

Margadonna, S. et al. Pressure evolution of the low-temperature crystal structure and bonding of the superconductor FeSe (T c = 37 K). Phys. Rev. B 80, 064506 (2009).

Tomita, T. et al. Correlation between T c and crystal structure in s-doped FeSe superconductors under pressure: studied by x-ray diffraction of FeSe0.8S0.2 at low temperatures. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 84, 84–93 (2015).

Sefat, A. S. Pressure effects on two superconducting iron-based families. Rep. Prog. Phys. 74, 124502 (2011).

Tafti, F. F. et al. Sudden reversal in the pressure dependence of T c in the iron-based superconductor KFe2As2. Nat. Phys. 9, 349–352 (2013).

Taufour, V. et al. Upper critical field of KFe2As2 under pressure: a test for the change in the superconducting gap structure. Phys. Rev. B 89, 220509(R) (2014).

Terashima, T. et al. Two distinct superconducting states in KFe2As2 under high pressure. Phys. Rev. B 89, 134520 (2014).

Tafti, F. F. et al. Universal V-shaped temperature-pressure phase diagram in the iron-based superconductors KFe2As2, RbFe2As2, and CsFe2As2. Phys. Rev. B 91, 054511 (2015).

Ying, J.-J. et al. Tripling the critical temperature of KFe2As2 by carrier switch. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1501.00330 (2015).

Wang, B. et al. Absence of superconductivity in the collapsed tetragonal phase of KFe2As2 under hydrostatic pressure. Phys. Rev. B 94, 020502(R) (2016).

Yang, J. et al. New superconductivity dome in LaFeAsO1-xFx accompanied by structural transition. Chin. Phys. Lett. 32, 107401 (2015).

Hiraishi, M. et al. Bipartite magnetic parent phases in the iron oxypnictide superconductor. Nat. Phys. 10, 300 (2014).

Song, C. L. et al. Observation of double-dome superconductivity in potassium-doped FeSe thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 157001 (2016).

Shiota, T. et al. Multiple antiferromagnetic spin fluctuations and novel evolution of T c in iron-based superconductors LaFe(As1−xPx)(O1−yFy) revealed by 31P-NMR studies. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 85, 053706 (2016).

Mukuda, H. et al. Emergence of novel antiferromagnetic order intervening between two superconducting phases in LaFe(As1-xPx)O: 31P-NMR studies. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 83, 083702 (2014).

Kinouchi, H. et al. Emergent phases of nodeless and nodal superconductivity separated by antiferromagnetic order in iron-based superconductor (Ca4Al2O6)Fe2(As1−xPx)2: 75As- and 31P-NMR studies. Phys. Rev. B 87, 121101(R) (2013).

Norman, M. R. The challenge of unconventional superconductivity. Science 332, 196 (2011).

Yuan, H. Q. et al. Observation of two distinct superconducting phases in CeCu2Si2. Science 302, 5653 (2003).

Tresca, C., Giovannetti, G., Capone, M. & Profeta, G. Electronic properties of superconducting FeS. Phys. Rev. B 95, 205117 (2017).

Lin, H. et al. Multi-band superconductivity and large anisotropy in FeS crystals. Phys. Rev. B 93, 144505 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (Grant No. 2015CB921401, and 2016YFA0300503), the Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 91421101, 11422429, 11421404, 51527801, U1530402), Program for Professor of Special Appointment (Eastern Scholar) at Shanghai Institutions of Higher Learning, and STCSM of China (No. 15XD1500200). W.Y. acknowledges the financial support from DOE-BES X-ray Scattering Core Program under grant number DE-FG02-99ER45775. We acknowledge Dr. Changyong Park for the assistance of beamline setup during the high-pressure XRD experiments. HPCAT operations are supported by DOE-NNSA under Award No. DE-NA0001974 and DOE-BES under Award No. DE-FG02- 99ER45775, with partial instrumentation funding by NSF. APS was supported by DOE-BES, under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.P.Y. and Y.J.Y. grew the single crystals. J.Z., F.L.L., Y.X. and M.X.W. performed the high-pressure resistance measurements. J.Z., X.C.H. and L.P.H. analyzed the transport data. F.L.L. and W.G.Y. performed the high-pressure XRD measurements. F.L.L, N.N.L. and W.G.Y. analyzed the XRD data. J.Z., F.L.L., T.P.Y., W.G.Y. and S.Y.L. wrote the manuscript. S.Y.L. and W.G.Y. conceived and designed the project. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results and revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, J., Liu, FL., Ying, TP. et al. Observation of two superconducting domes under pressure in tetragonal FeS. npj Quant Mater 2, 49 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-017-0050-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41535-017-0050-7

This article is cited by

-

Hydrothermal Synthesis and Transport Properties of FeS1-xTex (0 ≤ x ≤ 0.15) Single Crystals

Journal of Superconductivity and Novel Magnetism (2021)

-

Nanocrystalline Iron Monosulfides Near Stoichiometry

Scientific Reports (2018)

-

A brief review on μSR studies of unconventional Fe- and Cr-based superconductors

Science China Physics, Mechanics & Astronomy (2018)