Abstract

Superconducting integrated circuits have demonstrated a tremendous potential to realize integrated quantum computing processors. However, the downside of the solid-state approach is that superconducting qubits suffer strongly from energy dissipation and environmental fluctuations caused by atomic-scale defects in device materials. Further progress towards upscaled quantum processors will require improvements in device fabrication techniques, which need to be guided by novel analysis methods to understand and prevent mechanisms of defect formation. Here, we present a technique to analyse individual defects in superconducting qubits by tuning them with applied electric fields. This provides a spectroscopy method to extract the defects’ energy distribution, electric dipole moments, and coherence times. Moreover, it enables one to distinguish defects residing in Josephson junction tunnel barriers from those at circuit interfaces. We find that defects at circuit interfaces are responsible for about 60% of the dielectric loss in the investigated transmon qubit sample. About 40% of all detected defects are contained in the tunnel barriers of the large-area parasitic Josephson junctions that occur collaterally in shadow evaporation, and only \(\approx\)3% are identified as strongly coupled defects, which presumably reside in the small-area qubit tunnel junctions. The demonstrated technique provides a valuable tool to assess the decoherence sources related to circuit interfaces and to tunnel junctions that is readily applicable to standard qubit samples.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Superconducting qubits are implemented from resonant modes in non-linear electric microcircuits tailored from superconducting inductors, capacitors, and Josephson tunnel junctions.1,2 Prototype quantum processors comprising a few tens of coupled qubits have already demonstrated quantum simulations of small molecules,3 error correction,4 and complex algorithms.5 However, progress during the past decade was mostly achieved by improved circuit designs that reduced the interaction strength of qubits with material defects that are limiting device coherence.6,7 Since this strategy has seemingly exhausted its potential, further advancement will require an intense effort to understand and prevent the formation of defects in device fabrication.

Electric-field tuning of defects coupled to a superconducting resonator has been used to obtain information on their electric dipole moment sizes and densities,8 to control their population via Landau–Zener transitions,9 and to realize microwave lasing.10 Moreover, it served to investigate decoherence sources in disordered superconductors,11 and AC-electric field modulation of defect baths may provide a path to decouple them from a resonator or qubit.12

There are a variety of microscopic models of how defects may emerge in quantum circuits, some of which are illustrated in Fig. 1. A prominent class are structural tunnelling systems known from glasses, which are formed by a single or a few atoms tunnelling between two configurations in a disordered material.13,14 This creates parasitic quantum two-level systems (TLS), which couple via their electric dipole moment to the oscillating electric fields in quantum circuits. Due to the material’s random structure, TLS resonance frequencies are widely distributed, and those that are near resonance with qubits can dominate qubit energy relaxation.15 Moreover, the thermal activation of low-energy TLS causes resonance frequency fluctuations of high-energy TLS, resonators, and qubits, which occur on time-scales spanning from milliseconds to hours and days.16,17,18,19,20,21 For quantum processors, this implies that each qubit needs to be frequently recalibrated, while individual qubits can also become completely unusable due to randomly occurring resonant interaction with fluctuating TLS.

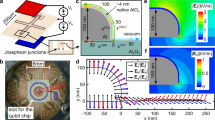

Overview of defect types in superconducting qubits. a Photograph of the cross-shaped capacitor electrode of a transmon qubit that is connected to the ground plane via Josephson junctions.22 Inset: The small junctions are contacted via large-area parasitic junctions (shaded orange). b Illustration of defect types in the amorphous AlOx tunnel barrier of a Josephson junction, indicating atomic tunnelling systems, hydrogen impurities, and trapped electrons. c Sketch of surface defects, showing a cross-section of the qubit electrode and its native aluminium oxide which hosts structural TLS (not to scale). In addition, adsorbates such as hydrogen (H) and molecular oxygen (O2) provide surface spins. Fabrication residuals such as photoresist, atmospheric contaminants, and substrate surface amorphization due to circuit patterning are further sources of surface defects.

Parasitic atomic tunnelling systems are contained in the amorphous aluminium oxide that grows natively on qubit circuit electrodes and which is used as a tunnel barrier in Josephson junctions. It is also assumed that structural tunnelling defects emerge from fabrication residuals such as photoresist,23 from impurity atoms such as interstitial hydrogen,24,25 and due to damage of crystalline substrates by inadequate cleaning or film patterning procedures.26 A further source of defects are surface adsorbates, such as hydrogen atoms and O2-molecules, whose unpaired spins have long been blamed as the major source of low-frequency (1/f-) noise in DC-SQUIDs and flux qubits,27 and which were recently reported to contribute also to charge noise.28

Results

In this article, we describe a technique to manipulate surface defects which are residing at qubit circuit interfaces, such as the substrate–metal, the substrate–vacuum, or the metal–vacuum interfaces. For this, the sample is exposed to a global DC-electric field generated by electrodes surrounding the chip as illustrated in Fig. 2a. A surface defect responds to the field with a change of its asymmetry energy \(\varepsilon\), which together with its (constant) tunnelling energy \(\Delta\) determines its resonance frequency, \({f}_{{\rm{TLS}}}=\sqrt{{\Delta }^{2}+{\varepsilon }^{2}}/h\). The global DC-electric field does not generate any field in the junction’s tunnel barriers, because the small charging energy of the transmon qubit allows Cooper-pairs to compensate any induced charge by tunnelling off or onto the island.29 Thus, TLS inside the tunnel barrier of a small or large (parasitic) junction do not respond to the applied external electric field and can hereby be distinguished from surface defects.

Tuning defects by mechanical strain and electric field. a Sketch of the setup for defect manipulation. The mechanical strain is controlled by the voltage \({V}_{{\rm{piezo}}}\) applied to a piezo actuator which slightly bends the qubit chip. The electric field is generated by two electrodes connected to a DC-voltage source \({V}_{{\rm{DC}}}\). b Pulse sequence-realizing defect spectroscopy by measuring the frequency-dependence of the qubit’s energy relaxation time \({T}_{1}\). c TLS resonance frequencies (dark traces indicating reduced \({T}_{1}\) time due to resonant interaction with defects) in dependence of applied mechanical strain. The horizontal line at 6.18 GHz is the resonance of a second qubit on the same chip. d Electric-field dependence of TLS resonance frequencies, plotted as a function of the voltage \({V}_{{\rm{DC}}}\) applied between the two electrodes. Hyperbolic traces stem from surface TLS at film interfaces, while horizontal lines reveal TLS residing in the tunnel barrier of a Josephson junction where they are screened from the electric field.

In addition, our setup allows us to tune all defects, irrespective of their location in the circuit, by mechanical strain that is generated via a piezo actuator slightly bending the qubit chip.30 In earlier experiments on phase qubits, the strain-tuning technique has proven useful to reveal mutual TLS interactions31 and to probe the coherent quantum dynamics of TLS to quantify their coupling to the bath of thermally fluctuating defects.20,32 Here, we use it to verify that also defects that do not respond to the electric field behave according to the standard tunnelling model, and to enhance the number of observable defects that are not tuned by the electric field.

In our experiments, we detect defects by measuring the frequency-dependence of the qubit’s energy relaxation rate \(1/{T}_{1}\), where local maxima indicate enhanced dissipation due to resonant interaction with individual TLS. A fast method uses the swap-spectroscopy protocol shown in Fig. 2b, where the qubit is populated by a microwave \(\pi -\)pulse, tuned to various probe frequencies using a variable-amplitude flux pulse, and afterwards read out.31,33 To economize time, we use a fixed flux pulse duration and take only two further reference measurements at zero flux pulse amplitude to estimate the energy relaxation rate (see Supplementary Material for details). The flux pulse duration is set to about half the qubit’s T1 time in order to balance signal loss against sensitivity to weakly interacting defects.

Figure 2 presents exemplary data taken with a transmon qubit in Xmon-geometry that was fabricated at UCSB as described in ref. 22 The strain-dependence of the qubit’s \({T}_{1}\) time, plotted as a function of the applied piezo voltage \({V}_{{\rm{piezo}}}\) in Fig. 2c, shows that the resonance frequency of all detectable TLS follows the expected hyperbolic dependence. In contrast, the horizontal lines in the electric field dependence Fig. 2d reveal a subset of defects that do not respond to the applied field as it is expected if they reside inside the tunnel barrier of a Josephson junction. Simulations of the induced electric fields (see Supplementary Material) were used to verify that all detectable surface defects, i.e. those that couple sufficiently strongly to the field induced by the qubit’s plasma oscillation, should also respond to the applied field.

In order to characterize the TLS’ response to the two types of stimuli more systematically, we alternate between strain and electric field sweeps. This results in data as shown in Fig. 3a, where the strain was linearly increased in segments with blue margins and the E-field was swept in red-framed segments. To extract the TLS’ sensitivities to strain \({\gamma }_{{\mathrm {S}}}\) and to electric field \({\gamma }_{{\mathrm {E}}}\), we fit each visible trace to the hyperbolic resonance frequency dependence with the TLS’ asymmetry energy \(\varepsilon ({V}_{{\rm{piezo}}},{V}_{{\rm{DC}}})={\varepsilon }_{{\mathrm {i}}}+{\gamma }_{{\mathrm {S}}}\cdot {V}_{{\rm{piezo}}}+{\gamma }_{{\mathrm {E}}}\cdot {V}_{{\rm{DC}}}\). Here, \({\gamma }_{{\mathrm {E}}}\) is proportional to the TLS’ electric dipole moment component that is parallel to the local electric field, and \({\varepsilon }_{{\mathrm {i}}}\) is an intrinsic offset energy. A few exemplary fits are indicated by highlighted traces in Fig. 3a. The distribution of extracted field sensitivities \({\gamma }_{{\mathrm {E}}}\) is plotted in Fig. 3c. We find that from a total of 260 observed TLS in two qubits, 40% do not respond to the electric field and thus reside in tunnel barriers—most likely in the large-area parasitic junctions as explained below. In contrast, all observed defects are tuned by mechanical strain as expected from the standard tunnelling model.

Statistics on the response to strain and electric field. a Alternating measurements of the mechanical strain (blue margins) and electric field dependence (red margins) of TLS resonance frequencies. Coloured trace highlights follow exemplary fits from which the TLS’ deformation potential \({\gamma }_{{\mathrm {S}}}\) and field coupling strength \({\gamma }_{{\mathrm {E}}}\) are obtained. b Vertical cross-section of the data shown in a (black dashed line), recalculated to the energy relaxation rate \(1/{T}_{1}\). Lorentzian fits to individiual TLS resonances Eq. (1) result in qubit–TLS coupling strengths \(g\) and TLS decoherence rates. The frequency step was 1 MHz. c Distribution of TLS sensitivities to electric field \({\gamma }_{{\mathrm {E}}}\). No response (\({\gamma }_{{\mathrm {E}}}\,<\) 1 kHz/V) is observed in 104/260 TLS (40\(\%\)). d Histograms of TLS–qubit coupling strengths \(g\) (left column) and TLS coherence times \({(\frac{1}{2}{\Gamma }_{{\rm{1,TLS}}}+{\Gamma }_{\Phi ,{\rm{TLS}}})}^{-1}\) (right column), plotted separately for TLS that do not respond to the field (top row) and for field-tunable TLS (bottom row). Similar coherence times of 50–100 ns are observed irrespective of the TLS’ response to electric field. The relatively small coupling strengths up to \(g\approx 0.2\,\) MHz indicate that nearly all defects which do not respond to the E-field are residing in the large-area parasitic junctions rather than the small qubit junctions.

The lineshape of the TLS resonances observed in \({T}_{1}\)-spectroscopy contains further information about the TLS’ decoherence rate and dipole moment size. After recalculating the data in Fig. 3a into the qubit energy relaxation rate \(1/{T}_{{\rm{1}}}\), each Lorentzian resonance is fitted to the equation22

where \(\Gamma =({\Gamma }_{{\rm{1,TLS}}}/2+{\Gamma }_{\Phi ,{\rm{TLS}}})+({\Gamma }_{{\rm{1,Q}}}/2+{\Gamma }_{\Phi ,{\rm{Q}}})\) is the sum of TLS and qubit energy relaxation and dephasing rates, and \(\delta\) is their detuning. The coupling strength \(g^{\prime} =(\overrightarrow{p}\ \cdot \overrightarrow{E})/\hslash\) between the qubit and a defect is the scalar product of the defect’s electric dipole moment \(\overrightarrow{p}\) and the local electric field \(\overrightarrow{E}\) induced by the qubit’s plasma oscillation. Figure 3b shows exemplary fits to Eq. (1) along the data marked by the black dashed line in Fig. 3a. We note that this provides the effective coupling strength \(g=g^{\prime} \cdot \Delta /\sqrt{{\Delta }^{2}+{\varepsilon }^{2}}\) that is dressed by the TLS’ matrix element which is typically unknown, but can be measured with strain-field or E-field spectroscopy if the TLS’ tunnel energy \(\Delta\) lies within the qubit’s tunability range.

In Fig. 3d, the distributions of TLS–qubit coupling strengths and TLS coherence times are plotted separately for junction-TLS that do not respond to the electric field (top row) and for field-tunable TLS residing at circuit interfaces (bottom row). Both classes show very similar qubit–TLS coupling strengths below \(g/2\pi \approx\) 0.4 MHz and typical TLS coherence times of 50–100 ns, in agreement with independent measurements on identically fabricated samples.22 On average, surface TLS are slightly stronger coupled to the qubit Xmon 1 because of its smaller gap between the qubit island and the ground plane as compared to Xmon 2 (see Supplementary Material).

Discussion

Considering field-tunable defects, the measured coupling strengths around \(g/2\pi \approx\) 0.1 MHz correspond to parallel dipole moment components of 0.2–0.4 eÅ, when they reside in the vicinity of the qubit electrode’s edge, where simulations indicate a plasma oscillation field strength of \(| E|\) = 10–20 V/m (see Supplementary Material). Measurements in AlOx15,34 and SiNx8 have found similar dipole moment sizes.

If the defects that do not respond to the applied E-field were inside the tunnel barrier of the qubit’s small Josephson junctions and had dipole moments of similar magnitude, one would expect much larger coupling strengths up to \(g/2\pi \approx 40\) MHz in contrast to our observation in Fig. 3d. However, in our sample, each qubit junction is connected to the ground plane via an additional larger “parasitic” or “stray” junction as a consequence of the employed shadow evaporation technique (see Fig. 1a). Since these junctions are connected in series, the voltage drop across each is inversely proportional to its area, resulting in a factor of \(\approx\)200 smaller electric fields in the larger parasitic junctions. TLS in these junctions thus couple at a strength of only \(g/2\pi \approx 0.1\) MHz when they have dipole moments of 0.3 eÅ, which is in excellent agreement with our measurements presented in Fig. 3d. Considering that junction and surface defects show similar coupling strengths and coherence times, we can conclude that in our sample \(40 \%\) of the qubit’s dielectric loss is due to defects in the parasitic Josephson junctions. This clearly shows the importance to avoid parasitic junctions by advanced fabrication methods, such as the ’bandaging’ technique where they are shorted by an additional metallization layer.26

The number of observable TLS resonances, averaged over all applied values of E-field and strain, was \({N}_{{\mathrm {p}}}\) = 15/GHz for TLS in the parasitic junctions and \({N}_{{\mathrm {s}}}\) = 23/GHz for surface TLS. For the parasitic junctions, this corresponds to a TLS density of P0,P = 250 GHz−1 μm−3 when assuming a tunnel barrier thickness of 2.5 nm. This density agrees with values in the range of 200–1200 GHz−1 μm−3 typically quoted for bulk dielectrics,35 and corresponds to a dielectric loss tangent36\(\tan {\delta }_{0,{\mathrm {p}}}=\pi {P}_{0,{\mathrm {p}}}\ {p}^{2}{(3{\epsilon }_{0}{\epsilon }_{{\mathrm {r}}})}^{-1}\approx 1.8\,\times\, 1{0}^{-4}\), where we chose \(p=0.4\) eÅ and \({\epsilon }_{{\mathrm {r}}}\approx 10\) for AlOx. This value is a factor of \(\approx\)10 smaller than typically quoted,15,37 presumably because it is based on the number of TLS traces that are clearly visible in swap spectroscopy, while contributions from weakly coupled TLS are not taken into account.

If the detected surface defects were distributed uniformly along the \(\approx\)1.4 mm-long edge of the qubit island, their average distance would be 60 μm. However, there are reasons to assume that surface defects may accumulate in the vicinity of the Josephson junctions where additional lithographic processing is required.26 This can be clarified in future experiments by employing a laterally positioned DC electrode.

Defects in the small tunnel junctions can be identified by their strong coupling to the qubit. This gives rise to avoided level crossings, which we reveal by monitoring the qubit’s resonance peak as a function of the applied strain. Figure 4a shows exemplary data which typically display up to three splittings larger than 5 MHz in our accessible strain range. Comparing this number to the \(\approx\)40 TLS per qubit found in the parasitic junctions, the result comes closer to the ratio of the junction’s circumferences (\(\approx\)14) than their area ratio (\(\approx\)200). This gives a hint that defects might predominantly emerge at junction edges.

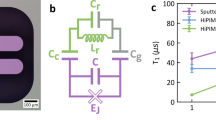

Detection of strongly coupled defects. a Qubit spectroscopy, taken by a long microwave pulse of varying frequency (vertical axis) to observe the qubit resonance (red colour, see also right inset). Variation of the mechanical strain (horizontal axis) reveals avoided level crossings due to strongly coupled TLS that are tuned through the qubit resonance. b Qubit \({T}_{1}\)-time measurement as a function of the applied DC-electric field. Lorentzian dips indicate resonant coupling to surface TLS. c In about 3\(\%\) of observed dips in the qubit’s \({T}_{1}\) time, damped oscillations are observed (blue curve), which herald quantum state swapping between the qubit and coherent surface TLS. In all other cases, purely exponential decay is found (red curve, fitted by black dashed line).

Finally, we test the coherence and coupling strength of surface TLS directly by observing coherent swap oscillations in resonantly coupled qubit–TLS systems.33 For this, the qubit population decay is observed in a \({T}_{1}\)-time measurement for a range of applied electric fields. Figure 4b shows the qubit’s \({T}_{1}\) time extracted from fits to exponential decay curves, which displays minima whenever the applied field tuned a TLS into resonance with the qubit. In about 3\(\%\) of more than 100 investigated \({T}_{1}\)-minima, we observed coherent swap oscillations with frequencies \(g/2\pi\) = 150–520 kHz as shown in Fig. 4c. This small subset of surface TLS thus has coherence times of a few microseconds, probably because they were close to their symmetry points where dephasing is suppressed.32

To summarize, our results confirm that defects residing at the substrate–metal, substrate–vacuum, and metal–air interfaces are a limiting factor of coherence in contemporary superconducting qubits. Parasitic (stray) junctions must be avoided, since they host large numbers of defects. So far, all experiments studying individual defects in superconducting qubits can be explained by a single type of defect having typical electric dipole moments \(| \overrightarrow{p}| \approx\) 0.1–1 eÅ and coherence times of typically 100 ns, in seldom cases extending up to a few μs.

The presented technique distinguishes defects in the tunnel barriers of Josephson junctions from those at surfaces. It provides a diagnostic tool to improve device fabrication by assessing the quality of tunnel junctions and circuit surfaces. This method can be easily implemented and applied to a variety of superconducting qubit types. Actually, a single electrode that is biased against the on-chip ground plane is sufficient to clearly distinguish surface-TLS from tunnel barrier defects.

Using multiple separately biased electrodes, it becomes possible to pinpoint the location of individual defects by comparing their response to simulations of the spatially dependent electric fields. As we will describe elsewhere, our current setup using two electrodes as sketched in Fig. 2a already suffices to distinguish defects on the substrate–metal, the substrate–vacuum, and the metal–vacuum interfaces. Lastly, we note that integration of on-chip electrodes or gates for direct voltage-biasing of transmon qubit islands offers a way to in situ mitigate decoherence in qubits that happen to be near resonance with a surface defect, facilitating the path towards scaled-up quantum processors.

Methods

Transmon qubit sample

The qubit sample was fabricated by Barends et al. as described in ref. 22 We measured a chip containing three uncoupled Xmon qubits which differ by the geometry of the coplanar qubit capacitor, having a width of S = 16 (24) μm for sample “Xmon1” (“Xmon2”), while the gap to the ground plane had a width of 8 (12) μm, respectively.

The qubit island, groundplane, and resonators are patterned from aluminium deposited by molecular beam epitaxy on a sapphire substrate. The Josephson junctions of the DC-SQUID connecting the qubit island to ground are fabricated by eBeam shadow evaporation. Each arm of the DC-SQUID contains a small tunnel junction of size 0.3 × 0.2 μm2 in a series connection with a larger “parasitic” junction of size 4.0 × 2.9 μm2.

Experimental setup

The sample was measured in an Oxford Kelvinox 100 wet dilution refrigerator at a temperature of 30 mK. The qubit chip was installed in a light-tight aluminium housing surrounded by a cryoperm magnetic shield. All coaxial cable connections to the qubit were heavily attenuated, filtered, and equipped with custom-made infrared filters. A standard homodyne microwave detection setup was used to read out the qubit state by measuring the dispersive shift of a readout resonator capacitively coupled to the qubit and a common transmission line.

The electrodes for electric-field tuning of defects were connected via a twisted pair of enamelled wire equipped with an RC-lowpass filter at the 1 K-stage that had a cutoff frequency of about 10 kHz. The top electrode consists of a copper-foil/Kapton foil stack that is glued to the lid of the sample box. The bottom electrode is patterned into the backside of the printed circuit board carrying the qubit chip, and has the form of a ring to leave space for the piezo exerting force to the centre of the qubit chip.

Simulations of electric fields

The electric fields generated by the qubit plasma oscillation and the fields induced by the global electrodes are simulated using the finite element solver ANSYS Maxwell. This showed that only TLS residing within a distance of \(\approx\)200 nm to the edge of the qubit island experience field strengths that couple them strongly enough to the qubit to be detected with our sample. Simulations also confirmed that within this distance, the absolute strength of the globally applied E-field as well as its projection onto the TLS’ electric dipole moment is large enough to result in detectable TLS detuning.

The Supplementary Material contains further details on spectroscopy methods, E-field simulations, and plots of complete data sets from strain-field and E-field-dependent defect spectroscopy.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Wendin, G. Quantum information processing with superconducting circuits: a review. Rep. Prog. Phys. 80, 106001 (2017).

Devoret, M. H. & Schoelkopf, R. J. Superconducting circuits for quantum information: an outlook. Science 339, 1169–74 (2013).

Kandala, A. et al. Hardware-efficient variational quantum eigensolver for small molecules and quantum magnets. Nature 549, 242 (2017).

Ofek, N. et al. Extending the lifetime of a quantum bit with error correction in superconducting circuits. Nature 536, 441 (2016).

Otterbach, J. et al. Unsupervised machine learning on a hybrid quantum computer. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1712.05771 (2017).

Wang, C. et al. Surface participation and dielectric loss in superconducting qubits. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 162601 (2015).

Gambetta, J. M. et al. Investigating surface loss effects in superconducting transmon qubits. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 27, 1–5 (2017).

Sarabi, B., Ramanayaka, A. N., Burin, A. L., Wellstood, F. C. & Osborn, K. D. Projected dipole moments of individual two-level defects extracted using circuit quantum electrodynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 167002 (2016).

Khalil, M. S. et al. Landau-zener population control and dipole measurement of a two-level-system bath. Phys. Rev. B 90, 100201 (2014).

Rosen, Y. J., Khalil, M. S., Burin, A. L. & Osborn, K. D. Random-defect laser: Manipulating lossy two-level systems to produce a circuit with coherent gain. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 163601 (2016).

le Suer, H. et al. Microscopic charged fluctuators as a limit to the coherence of disordered superconductor devices. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1810.12801 (2018).

Matityahu, S. et al. Dynamical decoupling of quantum two-level systems by coherent multiple Landau–Zener transitions. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1903.07914 (2019).

Phillips, W. A. Two-level states in glasses. Rep. Prog. Phys. 50, 1657 (1987).

Anderson, P. W., Halperin, B. I. & Varma, C. M. Anomalous low-temperature thermal properties of glasses and spin glasses. Philos. Mag. 25, 1–9 (1972).

Martinis, J. M. et al. Decoherence in Josephson qubits from dielectric loss. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 210503 (2005).

Faoro, L. & Ioffe, L. B. Interacting tunneling model for two-level systems in amorphous materials and its predictions for their dephasing and noise in superconducting microresonators. Phys. Rev. B 91, 014201 (2015).

Müller, C., Lisenfeld, J., Shnirman, A. & Poletto, S. Interacting two-level defects as sources of fluctuating high-frequency noise in superconducting circuits. Phys. Rev. B 92, 035442 (2015).

Schlör, S. et al. Correlating decoherence in transmon qubits: low frequency noise by single fluctuators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 190502 (2019).

Klimov, P. et al. Fluctuations of energy-relaxation times in superconducting qubits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 090502 (2018).

Meißner, S. M., Seiler, A., Lisenfeld, J., Ustinov, A. V. & Weiss, G. Probing individual tunneling fluctuators with coherently controlled tunneling systems. Phys. Rev. B 97, 180505 (2018).

Burnett, J. et al. Decoherence benchmarking of superconducting qubits. npj Quantum Inf. 5, 54 (2019).

Barends, R. et al. Coherent josephson qubit suitable for scalable quantum integrated circuits. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 080502 (2013).

Quintana, C. M. et al. Characterization and reduction of microfabrication-induced decoherence in superconducting quantum circuits. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 062601 (2014).

Gordon, L., Abu-Farsakh, H., Janotti, A. & Van de Walle, C. G. Hydrogen bonds in Al2O3 as dissipative two-level systems in superconducting qubits. Sci. Rep. 4, 7590 (2014).

Holder, A. M., Osborn, K. D., Lobb, C. & Musgrave, C. B. Bulk and surface tunneling hydrogen defects in alumina. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 065901 (2013).

Dunsworth, A. et al. Characterization and reduction of capacitive loss induced by sub-micron josephson junction fabrication in superconducting qubits. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 022601 (2017).

Anton, S. M. et al. Magnetic flux noise in dc SQUIDs: temperature and geometry dependence. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 147002 (2013).

de Graaf, S. E. et al. Suppression of low-frequency charge noise in superconducting resonators by surface spin desorption. Nat. Commun. 9, 1143 (2018).

Schreier, J. A. et al. Suppressing charge noise decoherence in superconducting charge qubits. Phys. Rev. B 77, 180502 (2008).

Grabovskij, G. J., Peichl, T., Lisenfeld, J., Weiss, G. & Ustinov, A. V. Strain tuning of individual atomic tunneling systems detected by a superconducting qubit. Science 338, 232 (2012).

Lisenfeld, J. et al. Observation of directly interacting coherent two-level systems in an amorphous material. Nat. Commun. 6, 6182 (2015).

Lisenfeld, J. et al. Decoherence spectroscopy with individual TLS. Sci. Rep. 6, 23786 (2016).

Cooper, K. B. et al. Observation of quantum oscillations between a josephson phase qubit and a microscopic resonator using fast readout. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 180401 (2004).

Müller, C., Cole, J. H. & Lisenfeld, J. Towards understanding two-level-systems in amorphous solids-insights from quantum devices. Rep. Prog. Phys. 82, 124501 (2019).

Faoro, L. & Ioffe, L. B. Interacting tunneling model for two-level systems in amorphous materials and its predictions for their dephasing and noise in superconducting microresonators. Phys. Rev. B 91, 014201 (2015).

Gao, J. The Physics of Superconducting Microwave Resonators. Phd thesis, California Institute of Technology (2008).

Deng, C., Otto, M. & Lupascu, A. Characterization of low-temperature microwave loss of thin aluminum oxide formed by plasma oxidation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 043506 (2014).

Acknowledgements

J.L. is grateful for funding from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG), grant LI2446-1/2. A.B. acknowledges support from the Helmholtz International Research School for Teratronics (HIRST) and the Landesgraduiertenförderung-Karlsruhe (LGF). A.V.U. acknowledges support by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation NUST MISIS (contract no. K2-2017-081). This work was supported by Google.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L. performed the measurements and data analysis and wrote the manuscript. A.B. implemented the setup for defect tuning by mechanical strain and electric field, and performed simulations. The qubit sample was developed and fabricated by partners from Google. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lisenfeld, J., Bilmes, A., Megrant, A. et al. Electric field spectroscopy of material defects in transmon qubits. npj Quantum Inf 5, 105 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-019-0224-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41534-019-0224-1

This article is cited by

-

Hole-type superconducting gatemon qubit based on Ge/Si core/shell nanowires

npj Quantum Information (2023)

-

Two-level system hyperpolarization using a quantum Szilard engine

Nature Physics (2023)

-

Resolving Fock states near the Kerr-free point of a superconducting resonator

npj Quantum Information (2023)

-

Granular aluminium nanojunction fluxonium qubit

Nature Materials (2023)

-

Enhancing the coherence of superconducting quantum bits with electric fields

npj Quantum Information (2023)