Abstract

Enzymes dependent on nicotinamide cofactors are important components of the expanding range of asymmetric synthetic techniques. New challenges in asymmetric catalysis are arising in the field of deuterium labelling, where compounds bearing deuterium (2H) atoms at chiral centres are becoming increasingly desirable targets for pharmaceutical and analytical chemists. However, utilisation of NADH-dependent enzymes for 2H-labelling is not straightforward, owing to difficulties in supplying a suitably isotopically-labelled cofactor ([4-2H]-NADH). Here we report on a strategy that combines a clean reductant (H2) with a cheap source of 2H-atoms (2H2O) to generate and recycle [4-2H]-NADH. By coupling [4-2H]-NADH-recycling to an array of C=O, C=N, and C=C bond reductases, we demonstrate asymmetric deuteration across a range of organic molecules under ambient conditions with near-perfect chemo-, stereo- and isotopic selectivity. We demonstrate the synthetic utility of the system by applying it in the isolation of the heavy drug (1S,3’R)-[2’,2’,3’-2H3]-solifenacin fumarate on a preparative scale.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Deuteration has long been used to alter the properties of molecules across a broad range of disciplines, from physical and life sciences, to forensics and environmental monitoring1,2,3,4. Indeed, the presence of deuterium can have implications for molecular properties far beyond the augmented mass, including the alteration of spin characteristics (particularly valuable in nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy), vibrational states, optical properties, neutron scattering and even solubility4. One of the most significant impacts of deuteration is manifested by the so-called deuterium kinetic isotope effect (DKIE), where cleavage of a C-2H bond can be many times slower than for the C-1H counterpart3. For decades, DKIEs have been exploited to provide insight into the mechanisms of chemical and biological processes1,4,5. More recently, there has been interest in exploiting potential therapeutic benefits of the DKIE to alter the pharmacokinetic properties of drug candidates and their associated metabolic profiles3,6,7,8,9. Here, deuterium atoms serve to stabilise compounds against physiological degradation routes, such as racemisation and oxidation, leading to improved pharmacokinetic profiles, which allow for lower doses, as well as minimising or avoiding the production of potentially toxic metabolites3,8,10.

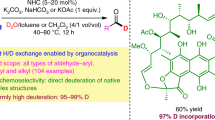

The interest in deutero-drugs has increased the demand for catalysts that are capable of precision deuteration8, installing deuterium atoms at well-controlled molecular positions. Hydrogen isotope exchange (HIE) and halogen–deuterium exchange catalysts allow for post-synthetic deuteration by treating the unlabelled compound in 2H2O or under 2H2 gas8,11,12. Developments in these catalysts have greatly improved the regio-selectivity of deuteration, with notable examples highlighted in Fig. 113,14,15,16. However, synthetic strategies for the enantioselective installation of deuterium are not well established. While a limited number of catalysts have been demonstrated for asymmetric HIE17,18,19, these post-synthetic methodologies can deteriorate the enantiomeric purity of the compound in question8. Similarly, there are limited examples of chemocatalysts for asymmetric reductive deuteration, and challenges remain around their enantio- and isotopic selectivity20,21,22.

In the field of asymmetric synthesis, biocatalysis has profoundly expanded the toolbox available to organic chemists, with enzymatic transformations offering near-perfect selectivity and mild operating conditions23. Advanced enzyme evolution techniques have dramatically expanded the scope of biocatalysis, with Sitagliptin providing a notable case study in biocatalytic pharmaceutical synthesis24. However, despite the growing importance of NADH-dependent reductase enzymes in chiral fine chemical synthesis25, significant hurdles have impeded their use in deuteration chemistry due to the requirement for deuterated, reduced cofactor, [4-2H]-NADH, which must be continually regenerated in situ (Fig. 2a). Demonstrations, at laboratory scale, have relied on a super-stoichiometric supply of a sacrificial deuterated reductant, [2H]-ethanol, [2H]-isopropanol, [2H]-glucose or [2H]-formate, for example, in conjunction with the appropriate dehydrogenase enzyme (Fig. 2b)26,27,28. Such compounds are labour intensive and expensive to prepare, adding cost and complexity to the process27. Conversely, researchers in the field of chemocatalytic deuteration have cited the desirability to use 2H2O as both the solvent and source of isotopes, owing to the inherent safety, cost efficiency, availability and easy handling of this material16,29. As such, we aimed to develop a method for conducting biocatalytic deuteration reactions whereby 2H could be incorporated directly from a heavy water reaction medium.

a Biocatalytic reductive deuteration requires a supply of [4-2H]-NADH. b Conventional [4-2H]-NADH-recycling strategies are driven by a sacrificial deuterated reductant. c Schematic representation of the heterogeneous biocatalytic system demonstrated in this work for H2-driven generation of the labelled cofactor [4-2H]-NADH, with 2H2O supplying the deuterium atoms. For complete structures of the cofactors, see Supplementary Fig. 1 and for details of the heterogeneous biocatalyst, see Supplementary Methods.

We have previously demonstrated H2-driven NADH recycling using hydrogenase and NAD+ reductase (both produced in-house, Supplementary Methods) co-immobilised on a carbon support30,31. This heterogeneous biocatalyst system couples H2 oxidation by a nickel-iron hydrogenase to the reduction of NAD+ to NADH by a flavin-containing NAD+ reductase moiety via electron transfer through the carbon31. Since the H2 oxidation and NAD+ reduction catalytic sites are spatially separated, we hypothesised that operation of this system in 2H2O, instead of H2O, would enable the NAD+ reductase to transfer deuterium ions from solution to NAD+, thereby forming [4-2H]-NADH (Fig. 2c) even under H2 gas. This suggested the possibility of a route to recycling the deuterated cofactor, suitable for application in the biocatalysed synthesis of selectively deuterated chemicals, in which the heavy atom label is provided solely by the solvent, 2H2O. Here we report on the application of the H2-driven biocatalytic system for forming and recycling [4-2H]-NADH in an array of C=O, C=N and C=C bond reductions. The resulting products illustrate the high chemo-, regio-, stereo- and isotopic selectivity that can be achieved through enzymatic deuteration, all under mild reaction conditions, and with 2H2O as the only source of 2H. We then illustrate the synthetic utility of this biocatalytic approach in the preparation of deuterium-labelled asymmetric molecules, including deutero-drugs and drug fragments.

Results

H2-driven biocatalytic system for generation of [4-2H]-NADH

To test our hypothesis that the heterogeneous biocatalyst system would form deuterated NADH, we supplied it with 4 mM NAD+ in 2H2O under an atmosphere of H2 gas (see Supplementary Methods for details). Subsequent analysis by ultraviolet (UV)–visible and proton NMR (1H NMR) spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 4) confirmed that only the biologically relevant [4]-NADH was generated (at 97% conversion), with the anticipated incorporation of 2H at the [4]-position on the nicotinamide ring ([4-2H]-NADH)31.

Scope of biocatalytic reductive deuteration

Following this successful demonstration, we then sought to use H2-dependent biocatalysis to recycle [4-2H]-NADH to drive a range of NADH-dependent reductases. The selected reductases were all from commercial enzyme suppliers, and were chosen to cover three of the most prominent classes of reductive biotransformations: carbonyl reduction, carbonyl reductive amination, and alkene reduction. By operating the heterogeneous biocatalyst system with the relevant reductase in 2H2O, under mild reaction conditions (p2H 8.0, 1 bar H2, 20 °C), we were able to demonstrate reactions to form a diverse array of molecules bearing deuterium atoms in carefully controlled positions (Fig. 3, full reaction schemes and product characterisation in Supplementary Methods). A steady flow of H2 across the reaction headspace was found to be sufficient to drive the reactions, but conventional balloons and sealed pressure vessels were also shown to be suitable alternative setups. In all cases, the chemo-, stereo- and regio-selectivity known for the enzymatic reactions in natural abundance H2O was fully retained upon translation to the deuteration conditions.

Typical reaction conditions: 0.5 mL, 5 mM reagent, 0.5 mM NAD+, 2H2O (98 %), Tris-2HCl (p2H 8.0, 100 mM), 1–5 vol.% 2H6-DMSO, 16 h, 20 oC, 1 bar H2 and shaking at 500 r.p.m. Catalysts: Excess NADH-dependent reductase, 400 μg carbon (160 pmol hydrogenase, 260 pmol NAD+ reductase). For reductive amination reactions: 25 mM NH4Cl. *All transformations were fully selective for the reduction of the desired functional group except 6c, for which a known enzymatic side reaction yielded an extra product (see Supplementary Fig. 47 and associated discussion). Full experimental and analytical details are provided in Supplementary Methods.

The reductive deuteration of a suite of reagents, via H2-driven recycling of [4-2H]-NADH, was achieved by combining the heterogeneous biocatalytic cofactor recycling system with an appropriate reductase, either co-immobilised or in solution. The products in Fig. 3 demonstrate the versatility of this approach. For carbonyl reduction, for example, it was possible to generate either (S)-[1-2H]- or (R)-[1-2H]-1-phenylethanol (1a and 1b) from acetophenone, with ≥93% isotopic selectivity and ≥99% enantioselectivity, by choosing an (S)- or (R)-selective alcohol dehydrogenase (keto reductase), respectively. Similarly, 4-chloroacetophenone and 4-bromoacetophenone could be reduced to give the corresponding chlorinated (1c and 1d) and brominated (1e and 1f) products with similar selectivity, and preserving the aryl halide for potential onward cross-coupling chemistry. Pyruvate could be converted to l-[2-2H]-lactate (2) by the action of l-lactate dehydrogenase, or to l-[2-2H]-alanine (3) by the action of l-alanine dehydrogenase in the presence of an amine source (NH4+). Reductive amination was also carried out on phenylpyruvate using l-phenylalanine dehydrogenase; prior exchange of the β-protons with 2H2O yields a triply deuterated product: l-[2,2,3-2H3]-phenylalanine (4). Deuterated amino acids have been identified as particularly valuable targets owing to their pharmacological applications (such as [2H3]-d-serine and [2H3]-l-DOPA)32, and their use in protein NMR spectroscopy33.

Asymmetric alkene reduction was demonstrated by the use of an ene-reductase on (5R)- and (5S)-carvone reagents, yielding trans-(2 R,5R)- and cis-(2R,5S)-dideuterocarvone (5a and 5b), respectively. Here, the enzyme generates (R)-stereochemistry at the prochiral 2-position of the two parent carvones, with equally high de in each case. 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis of product 5a (see Supplementary Methods) demonstrates that the deuterium atom at the 3-position of the dideuterocarvone is also added asymmetrically, giving (R)-stereochemistry at this position, in accordance with the established mechanism of ene reductases in reducing double bonds in an anti-manner34,35. The ability to introduce isotopically induced chirality by selective biocatalytic deuteration may have further important implications in drug design and generation of deuterated chemicals for analytical applications36.

In a final screening experiment, we demonstrated the potential for chemo-selective deuteration of another molecule containing both alkene and carbonyl functionalities, αβ-unsaturated cinnamaldehyde. Reduction of cinnamaldehyde by means of conventional heterogeneous catalysis can suffer from poor chemoselectivity, giving rise to products from mixed reduction and over-reduction37. However, by utilising an ene-reductase and alcohol dehydrogenase in isolation or sequentially, the singly deuterated cinnamyl alcohol (6a), doubly deuterated hydrocinnamaldehyde (6b) or multiply deuterated 3-phenyl-1-propanol (6c) can all be separately prepared.

Application of catalyst for preparing deuterated drugs

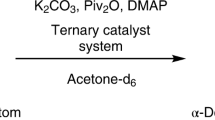

Following confirmation of the scope of the biocatalytic system for C=O, C=C and C=N bond reductive deuteration, the catalyst was tested for its applicability under standard benchtop synthesis conditions (10 mL reaction solution, round bottom flask, under gentle flow of H2). The chiral alcohol (R)-3-quinuclidinol was selected as the target compound for these studies, as it is a key component in a number of drug molecules, such as talsaclidine, cevimeline and solifenacin38,39. In order to synthesise the chiral alcohol, a quinuclidinone reductase from Agrobacterium tumefaciens (AtQR) was expressed in Escherichia coli and purified accordingly (Supplementary Methods)40,41. When supplied with NADH and 3-quinuclidinone, the AtQR is capable of producing (R)-3-quinuclidinol with >99% ee. As such, the AtQR was combined with the H2-driven deuteration catalyst in order to transfer a 2H-atom to the (3R)-chiral centre with equally high selectivity (see Fig. 4a). Here, the protons α to the amine and the carbonyl group in the substrate freely exchange with the 2H2O solvent, resulting in (R)-[2,2,3-2H3]-3-quinuclidinol as the final product. The reaction was conducted on a preparative scale (35 mg), and proceeded with the anticipated >99% ee and >98% 2H incorporation on the two carbon atoms (Supplementary Methods). The heterogeneous catalyst could simply be filtered off and, following basification and extraction, the product was obtained in a crude form in a near quantitative yield. The only contaminant at this stage was a trace amount of glycerol, which could likely be eliminated by exchanging the storage buffer of the enzymes prior to use. While precautions were taken to exclude O2, the use of the robust, O2-tolerant hydrogenase 1 from E. coli meant that the reaction did not need to be rigorously anaerobic to succeed42,43.

a Preparation of trideuterated (R)-3-quinuclidinol via biocatalytic reductive deuteration and b incorporation into the pharmaceutical compound (1S,3′R)-solifenacin fumarate. In each case, the mass spectroscopy traces show the expected +3 shift in m/z values of the isolated product (lower plot) relative to their natural abundance standards (upper plot). Full experimental and analytical details are provided in Supplementary Methods.

Having isolated sufficient quantities of (R)-[2,2,3-2H3]-3-quinuclidinol, the compound was used to generate a deuterated form of the antimuscarinic drug, solifenacin fumarate, on a scale suitable for onward biochemical investigation44,45. Conventional synthetic routes to the drug typically rely on crystallographic resolution of a racemate; however, that step was avoided here owing to the enantiomeric purity of the quinuclidinol moiety utilised44. Indeed, the simultaneous installation of the deuterium with the creation of the chiral centre is preferable to a post-synthetic deuteration strategy with a HIE catalyst, where the ee may be diminished. It is worth noting that the other chiral building block, (S)-1-phenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline, which we obtained commercially, has recently been shown to be accessible by different enzymatic strategies, and may also be targeted for asymmetric deuteration in a similar manner46,47,48. Following the synthesis, it was established that the stereo- and isotopic purity of the starting quinuclidinol was carried through to the final solifenacin fumarate product (see Fig. 4b and Supplementary Methods).

In summary, we have demonstrated a versatile approach to asymmetric reductive deuteration that exploits the near-perfect selectivity of NADH-dependent reductases. The system enables the formation of a deuterium-labelled chiral centre in a single step with high chemo-, stereo- and isotopic selectivity. The catalyst operates under mild conditions using a simple reductant (H2), coupled with a cheap and abundant source of deuterium (2H2O), and therefore represents a major advance compared to existing bio- and chemocatalytic deuteration strategies.

Initially, we showed high %2H incorporation across diverse functional group space to highlight that the major classes of NADH-dependent biocatalytic transformations (ketone reduction, ene reduction and reductive amination) can be achieved with retention of the original enzyme selectivity. The subsequent library of asymmetric [2H]-labelled molecules generated will be valuable to researchers across a diverse range of fields. In particular, asymmetric deuterium centres are increasingly desirable to synthetic medicinal chemists, so we further demonstrated the applicability of our system for the preparative-scale deuteration of the chiral drug fragment (R)-3-quinuclidinol. Here it was shown that the biocatalytic deuteration approach was fully compatible with standard benchtop synthetic techniques and hydrogenation protocols, with the advantage of relying on mild temperatures and H2 pressures. Furthermore, the use of H2 and 2H2O as reagents, catalytic quantities of cofactor and the use of carbon-supported enzymes mean that only very simple purification strategies are required, simplifying downstream transformations. This point was illustrated by the subsequent synthesis and isolation of a deuterated analogue of the incontinence drug, solifenacin. Notably, this strategy of introducing the isotope label in the same step as the formation of the chiral centre, allowed for the formation of the final product without the necessity of post-synthetic HIE.

Hence, by coupling the system reported here with the increasing range of available NADH-dependent enzymes, we anticipate that biocatalysis will provide a powerful complementary addition to the growing toolbox of deuterium incorporation techniques.

Data availability

All data are available from the authors upon reasonable request.

References

Yang, J. Deuterium: Discovery and Applications in Organic Chemistry 1–116 (Elsevier, 2016).

Hanson, J. R. in The Organic Chemistry of Isotopic Labelling (ed. Hanson, J. R.) 40–61 (RSC, 2011).

Gant, T. G. Using deuterium in drug discovery: leaving the label in the drug. J. Med. Chem. 57, 3595–3611 (2014).

Atzrodt, J., Derdau, V., Kerr, W. J. & Reid, M. Deuterium- and tritium-labelled compounds: applications in the life sciences. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 1758–1784 (2018).

Pudney, C. R., Hay, S. & Scrutton, N. S. Practical aspects on the use of kinetic isotope effects as probes of flavoprotein enzyme mechanisms. Methods Mol. Biol. 1146, 161–175 (2014).

Liu, J. F. et al. A decade of deuteration in medicinal chemistry. Annu. Rep. Med. Chem. 50, 519–542 (2017).

Foster, A. B. Deuterium isotope effects in studies of drug metabolism. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 5, 524–527 (1984).

Pirali, T., Serafini, M., Cargnin, S. & Genazzani, A. A. Applications of deuterium in medicinal chemistry. J. Med. Chem. 62, 5276–5297 (2019).

Schmidt, C. First deuterated drug approved. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 493–494 (2017).

Davey, S. Relief from racemization. Nat. Chem. 7, 368–368 (2015).

Atzrodt, J., Derdau, V., Kerr, W. J. & Reid, M. C−H functionalisation for hydrogen isotope exchange. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 3022–3047 (2018).

Atzrodt, J., Derdau, V., Fey, T. & Zimmermann, J. The renaissance of H/D exchange. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 7744–7765 (2007).

Nilsson, G. N. & Kerr, W. J. The development and use of novel iridium complexes as catalysts for ortho-directed hydrogen isotope exchange reactions. J. Labelled Compd. Radiopharm. 53, 662–667 (2010).

Yu, R. P., Hesk, D., Rivera, N., Pelczer, I. & Chirik, P. J. Iron-catalysed tritiation of pharmaceuticals. Nature 529, 195–199 (2016).

Loh, Y. Y. et al. Photoredox-catalyzed deuteration and tritiation of pharmaceutical compounds. Science 358, 1182–1187 (2017).

Liu, C. et al. Controllable deuteration of halogenated compounds by photocatalytic D2O splitting. Nat. Commun. 9, 80 (2018).

Taglang, C. et al. Enantiospecific C-H activation using ruthenium nanocatalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 10474–10477 (2015).

Palmer, W. N. & Chirik, P. J. Cobalt-catalyzed stereoretentive hydrogen isotope exchange of C(sp3)–H bonds. ACS Catal. 7, 5674–5678 (2017).

Hale, L. V. A. & Szymczak, N. K. Stereoretentive deuteration of α-chiral amines with D2O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 13489–13492 (2016).

Schlatter, A., Kundu, M. K. & Woggon, W.-D. Enantioselective reduction of aromatic and aliphatic ketones catalyzed by ruthenium complexes attached to β-cyclodextrin. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 6731–6734 (2004).

Noyori, R., Masashi, Y. & Hashiguchi, S. Metal–ligand bifunctional catalysis: a nonclassical mechanism for asymmetric hydrogen transfer between alcohols and carbonyl compounds. J. Org. Chem. 66, 7931–7944 (2001).

Carrión, M. C. et al. Selective catalytic deuterium labeling of alcohols during a transfer hydrogenation process of ketones using D2O as the only deuterium source. Theoretical and experimental demonstration of a Ru–H/D exchange as the key step. ACS Catal. 4, 1040–1053 (2014).

Turner, N. J. & Humphreys, L. Biocatalysis in Organic Synthesis: The Retrosynthesis Approach (RSC, 2018).

Savile, C. K. et al. Biocatalytic asymmetric synthesis of chiral amines from ketones applied to sitagliptin manufacture. Science 329, 305–309 (2010).

Prier, C. K. & Kosjek, B. Recent preparative applications of redox enzymes. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 49, 105–112 (2019).

Yahashiri, A., Sen, A. & Kohen, A. Microscale synthesis and kinetic isotope effect analysis of (4R)-[Ad-14C,4-2H] NADPH and (4R)-[Ad-3H,4-2H] NADPH. J. Labelled Compd. Radiopharm. 52, 463–466 (2009).

Wong, C. H. & Whitesides, G. M. Enzyme-catalyzed organic synthesis: regeneration of deuterated nicotinamide cofactors for use in large-scale enzymatic synthesis of deuterated substances. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 105, 5012–5014 (1983).

Edegger, K. et al. Biocatalytic deuterium- and hydrogen-transfer using over-expressed ADH-‘A’: enhanced stereoselectivity and 2H-labeled chiral alcohols. Chem. Commun. 5, 2402–2404 (2006).

Zhang, M., Yuan, X., Zhu, C. & Xie, J. Deoxygenative deuteration of carboxylic acids with D2O. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 312–316 (2019).

Reeve, H. A., Lauterbach, L., Ash, P. A., Lenz, O. & Vincent, K. A. A modular system for regeneration of NAD cofactors using graphite particles modified with hydrogenase and diaphorase moieties. Chem. Commun. 48, 1589–1591 (2012).

Reeve, H. A., Lauterbach, L., Lenz, O. & Vincent, K. A. Enzyme-modified particles for selective biocatalytic hydrogenation by hydrogen-driven NADH recycling. ChemCatChem 7, 3480–3487 (2015).

Pająk, M., Pałka, K., Winnicka, E. & Kańska, M. The chemo- enzymatic synthesis of labeled l-amino acids and some of their derivatives. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 317, 643–666 (2018).

Movellan, K. T. et al. Alpha protons as NMR probes in deuterated proteins. J. Biomol. NMR 73, 81–91 (2019).

Toogood, H. S. & Scrutton, N. S. New developments in ‘ene’-reductase catalysed biological hydrogenations. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 19, 107–115 (2014).

Toogood, H. S., Gardiner, J. M. & Scrutton, N. S. Biocatalytic reductions and chemical versatility of the old yellow enzyme family of flavoprotein oxidoreductases. ChemCatChem 2, 892–914 (2010).

Sato, I., Omiya, D., Saito, T. & Soai, K. Highly enantioselective synthesis induced by chiral primary alcohols due to deuterium substitution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 11739–11740 (2000).

Durndell, L. J. et al. Selectivity control in Pt-catalyzed cinnamaldehyde hydrogenation. Sci. Rep. 5, 9425 (2015).

Chavakula, R., Chakradhar Saladi, J. S., Shankar, N. G. B., Subba Reddy, D. & Raghu Babu, K. A large scale synthesis of racemic 3-quinuclidinol under solvent free conditions. Org. Chem. Ind. J. 14, 127–131 (2018).

Radman Kastelic, A. et al. New and potent quinuclidine-based antimicrobial agents. Molecules 24, 2675 (2019).

Hou, F. et al. Expression, purification, crystallization and X-ray analysis of 3-quinuclidinone reductase from Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F 68, 1237–1239 (2012).

Hou, F. et al. Structural basis for high substrate-binding affinity and enantioselectivity of 3-quinuclidinone reductase AtQR. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 446, 911–915 (2014).

Lukey, M. J. et al. How Escherichia coli is equipped to oxidize hydrogen under different redox conditions. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 3928–3938 (2010).

Reeve, H. A. et al. Enzymes as modular catalysts for redox half reactions in H2-powered chemical synthesis: from biology to technology. Biochem. J. 474, 215–230 (2017).

Trinadhachari, G. N. et al. An improved process for the preparation of highly pure solifenacin succinate via resolution through diastereomeric crystallisation. Org. Process Res. Dev. 18, 934–940 (2014).

Fuentes, G. G., Bonde-Larsen, A. L., del Campo López-Bachiller, J., Sandoval Rodríguez, C. & Sainz, Y. F. Solifenacin salts. US patent 8,765,785 B2 (2014).

Li, G. et al. Simultaneous engineering of an enzyme’s entrance tunnel and active site: the case of monoamine oxidase MAO-N. Chem. Sci. 8, 4093–4099 (2017).

Heath, R. S., Pontini, M., Bechi, B. & Turner, N. J. Development of an R-selective amine oxidase with broad substrate specificity and high enantioselectivity. ChemCatChem 6, 996–1002 (2014).

Wetzl, D. et al. Asymmetric reductive amination of ketones catalyzed by imine reductases. ChemCatChem 8, 2023–2026 (2016).

Acknowledgements

The research of K.A.V., H.A.R., M.A.R. and J.S.R. is supported by Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) IB Catalyst award EP/N013514/1. In addition, J.S.R. is grateful to Linacre College, Oxford for the support of an EPA Cephalosporin Junior Research Fellowship. O.L. thanks the Cluster of Excellence “Unifying Concepts in Catalysis” (EXC 314‐2, Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft) for support. Ailun Huang and Thomas Lonsdale are acknowledged for laboratory assistance in initial experiments. We thank Janina Preissler (TU Berlin) for assistance with the isolation and purification of the NAD+ reductase and E. Nomerotskaia (Univ. Oxford) for preparing E. coli hydrogenase 1. Dr. Beatriz Dominguez (Johnson Matthey) is gratefully acknowledged for providing (S)-ADH, (R)-ADH and ene-reductase enzymes, and Prof. Frank Sargent (Newcastle Univ.) is thanked for kindly providing samples of E. coli strain FTH004. Dr. James Wickens (Univ. Oxford) and Dr. Alistair Farley (Univ. Oxford) are thanked for helping to perform analysis by GC-MS/LC-MS. We are grateful to Dr. Robert Jacobs (Univ. Oxford) for thermal analysis, Dr. Kourosh Ebrahimi (Univ. Oxford) for HRMS analysis, and Stephen Boyer (London Metropolitan University) for elemental analysis of the product compounds. Finally, we thank Dr. Katrina Madden and Dr. Sarah Cleary for helpful comments on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.S.R., M.A.R., O.L., H.A.R. and K.A.V. all helped to design experiments; J.S.R. and M.A.R. performed experiments; H.A.R. and J.S.R. analysed data; all authors contributed to writing the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

A patent application by J.S.R., H.A.R. and K.A.V. detailing some of this research was filed through Oxford University Innovation (Feb 2018). The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Jens Atzrodt, Nicholas Turner and Wolf-D. Woggon for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rowbotham, J.S., Ramirez, M.A., Lenz, O. et al. Bringing biocatalytic deuteration into the toolbox of asymmetric isotopic labelling techniques. Nat Commun 11, 1454 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15310-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15310-z

This article is cited by

-

Deuterium in drug discovery: progress, opportunities and challenges

Nature Reviews Drug Discovery (2023)

-

Hydrogenative alkene perdeuteration aided by a transient cooperative ligand

Nature Chemistry (2023)

-

Visible-light mediated catalytic asymmetric radical deuteration at non-benzylic positions

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Analysing the relationship between the fields of thermo- and electrocatalysis taking hydrogen peroxide as a case study

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Light-driven decarboxylative deuteration enabled by a divergently engineered photodecarboxylase

Nature Communications (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.