Abstract

Chemical looping methane partial oxidation provides an energy and cost effective route for methane utilization. However, there is considerable CO2 co-production in current chemical looping systems, rendering a decreased productivity in value-added fuels or chemicals. In this work, we demonstrate that the co-production of CO2 can be dramatically suppressed in methane partial oxidation reactions using iron oxide nanoparticles embedded in mesoporous silica matrix. We experimentally obtain near 100% CO selectivity in a cyclic redox system at 750–935 °C, which is a significantly lower temperature range than in conventional oxygen carrier systems. Density functional theory calculations elucidate the origins for such selectivity and show that low-coordinated lattice oxygen atoms on the surface of nanoparticles significantly promote Fe–O bond cleavage and CO formation. We envision that embedded nanostructured oxygen carriers have the potential to serve as a general materials platform for redox reactions with nanomaterials at high temperatures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Syngas, i.e., CO and H2, is an important intermediate for producing fuels and value-added chemicals from methane via Fischer–Tropsch or other synthesis techniques1. Syngas has been produced commercially by steam reforming, autothermal reforming, and partial oxidation of methane for many decades2. However, an improvement of its energy consumption, environmental impact, and associated production cost has always been of interest. This has prompted the investigation into alternative routes that can avoid the use of air separation units for producing purified oxygen and are more effective in CO2 emission control. It is also of interest to reduce the operating temperature of these processes, which are generally endothermic and traditionally require temperatures of 900 °C or higher to attain high reactant conversion rates. The use of high temperatures is problematic because the thermodynamic driving force for carbon deposition, and thus materials obliteration, can be accelerated3. Current approaches to reducing reaction temperatures while avoiding side product formation require noble metals such as Pt, Pd, or Au, which leads to dramatic increases in cost4.

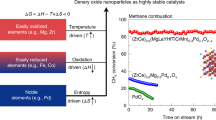

Chemical looping methane partial oxidation5 (CLPO) is an emerging approach that overcomes the above-mentioned shortcomings for syngas production. A CLPO process involves redox reactions taking place in two interconnected reactors: a reducer (or fuel reactor) and an oxidizer (also referred to as air reactor), shown in Fig. 1a. In contrast to conventional fossil fuel gasification and reforming processes, CLPO eliminates the need for an air separation unit, water–gas shift reactor, and acid gas removal unit. It has the potential to directly produce high-quality syngas with desirable H2:CO ratios. The core of CLPO using natural gas as the feedstock involves complex redox reactions in which methane molecules adsorb and dissociate on metal oxide oxygen carrier surfaces. It also involves internal lattice oxygen ion diffusion in which oxygen vacancy creation and annihilation occurs. These reactions can be engineered to withstand thousands of redox cycles5.

The recent progress in chemical looping technology for partial oxidation has advanced to the stage where successful pilot operation has been demonstrated and proven to be highly efficient with a minimal energy penalty in the process applications6. In this technology, the highest CO selectivity that the CLPO can reach is thermodynamically limited to 90% with accompanied 10% CO2 generation. It is recognized that the CO2 reduction in low purity syngas is extremely challenging and energy consuming, as CO2 is among the most chemically stable carbon-based molecules7. This 10% of CO2 in syngas can significantly reduce the productivity of value-added fuels or chemicals generated. Breaking away from the 90% CO yield limits to achieve near 100% CO selectivity requires a different consideration from the metal oxide materials design and synthesis perspective.

We report an approach to metal oxide oxygen carrier engineering for CLPO by designing and synthesizing nanoscale iron oxide carriers8 embedded in mesoporous silica SBA-15 (Fe2O3@SBA-15). Mesoporous silica is an engineered nanomaterial that has high surface area, ordered pore structures, and high tunability of morphology. Its unique properties have attracted broad attention in a number of applications such as environmental treatment, catalysis, and biomedical engineering9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. SBA-15 is a common mesoporous silica that has perpendicular nanochannels with a narrow pore size distribution which is suitable for nanoparticle separation and gas penetration. A schematic of our materials platform is outlined in Fig. 1a. We experimentally achieve a high CO selectivity >99%, which is by far the highest in CLPO systems (Fig. 1b). We also find that cyclic methane partial oxidation with nanoscale oxygen carrier materials can be performed with high selectivity at temperatures as low as 750 °C. These findings underscore the strong size-dependent effects of metal oxide oxygen carriers at the nanoscale on syngas selectivity and reactant conversion in redox processes. This work will have broader impacts not only on CLPO, but also on other chemical looping applications such as carbonaceous fuel conversion and utilization.

Results

Characteristics of Fe2O3@SBA-15

Figure 2 shows the transmission electron microscope (TEM) images of Fe2O3@SBA-15 before and after redox cycles with no obvious morphological distinction. Nanoparticles with a size of 3–5 nm can be identified as α-Fe2O3 based on lattice fringes measurement in which a = b = 5.038 Å and c = 13.772 Å. Element mapping is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1, suggesting that Fe2O3 nanoparticles are embedded in SBA-15 nanochannels. The TEM images also confirm that the nanoparticles remain embedded in SBA-15 nanochannels with identical morphology after 75 redox cycles. The particle size slightly increases to 5–8 nm after 75 redox cycles due to unavoidable morphology evolution. This result indicates the high stability of Fe2O3@SBA-15 at high temperatures.

The mesoporous silica SBA-15 (Supplementary Fig. 2) exhibits a surface area of 550 m2 g−1, a uniform pore size of 8 nm, and a pore volume of 0.66 cm3 g−1 (Supplementary Methods). The pore volume decreases to 0.52 cm3 g−1 which is 23% less than SBA-15 after Fe2O3 nanoparticle loading, implying a Fe2O3 nanoparticle volume loading of ~20%. The average pore size remains at 8 nm with a minor decrease in magnitude, indicating that the silica nanochannels are partially filled by Fe2O3 nanoparticles.

In comparison, Supplementary Fig. 3a, c suggests that the unsupported Fe2O3 nanoparticles are agglomerated with a wide size distribution of 50–100 nm. Supplementary Fig. 3b, d reveals that the nanoparticles will evolve to microparticles of 1–10 µm after 75 redox cycles. On the other hand, the morphology of Fe2O3@SBA-15 arrays before and after 75 redox cycles (Supplementary Fig. 3e, f) remain almost unchanged, indicating high recyclability of Fe2O3@SBA-15 at both nanoscale and microscale.

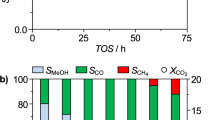

Methane CLPO with Fe2O3@SBA-15

The reactivity and recyclability test results are shown in Fig. 3. A stable CO2 concentration of <0.7% gO−1 is observed in Fe2O3@SBA-15 throughout methane partial oxidation, indicating a high syngas selectivity higher than 99.3%. In unsupported Fe2O3, CO2 formation is observed to increase with temperature, resulting in an average selectivity less than 87%. In the range of 750–935 °C, CO concentration from Fe2O3@SBA-15 is over 200% higher than unsupported Fe2O3, suggesting a near 100% CO selectivity with significantly higher CO conversion rate.

Over 75 continuous redox cycles were carried out on both Fe2O3 samples with and without SBA-15 support (Supplementary Fig. 4). Five typical TGA redox cycles are shown in Fig. 3b. The high recyclability is consistent with TEM observation. Fe2O3@SBA-15 not only has a high conversion rate, but is stable at high temperatures. This suggests that the separation of nanoparticles is essential in maintaining high CO selectivity, reactivity, and recyclability. At 800 °C, the conversion rate of Fe2O3@SBA-15 is 67% higher than unsupported Fe2O3. The morphology of post redox nanoparticles can be found in Fig. 2b, where Fe2O3@SBA-15 nanochannels remain almost identical to fresh samples. This demonstrates the high stability and anti-sintering effect of dispersed nanostructures at high temperatures. The average pore size of Fe2O3@SBA-15 is 7.6 nm after 75 redox cycles (Supplementary Fig. 5), which confirms high cyclic stability.

The methane conversion and syngas selectivity of both unsupported Fe2O3 and Fe2O3@SBA-15 were also evaluated in a quartz U-tube (1 cm diameter) fixed bed reactor. As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 6, a high selectivity near 100% in Fe2O3@SBA-15 is confirmed in both TGA and fixed bed reactor and a higher methane conversion is also obtained compared with unsupported Fe2O3 with different weight hourly space velocity (WHSV).

Size-dependent reaction modeling

To gain mechanistic insight into the role of the nanostructures in CO selectivity enhancement of Fe2O3@SBA-15, first-principles calculations were performed within the framework of density functional theory (DFT) using the Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP)18,19,20. To take into consideration realistic experimental conditions (800 °C for CH4 partial oxidation), the temperature effect is included by explicitly taking into account adsorbed CH4 molecules in terms of ab initio atomistic thermodynamics. The theoretical description requires the size and geometry of the model to be as realistic as possible, for direct comparison with experimental samples. However, modeling (Fe2O3)n nanoparticles of realistic size (>3 nm) by first-principles calculations is very demanding and the global optimization is hardly feasible. In this work, (Fe2O3)60 (~2 nm) is modeled as the largest nanoparticle to examine the size effect. Figure 4 shows calculated energies of CH4 adsorption on Fe atop site and O atop site of (Fe2O3)n nanoparticles as a function of n, and the corresponding adsorption geometries are described in Supplementary Fig. 7. The data of the previous computational study on CH4 adsorption on Fe2O3 (001) surface are given by the filled circle21. It can be seen that CH4 adsorption energies dramatically decrease with increasing number, n when the sizes of Fe2O3 nanoparticles are at a relatively small scale. However, they decrease slowly with increasing n when the sizes are at relatively large scale. The strongest adsorption on (Fe2O3)4 is CH4 binding at the Fe atop site with an adsorption energy of 66.2 kJ mol−1. The second stable configuration is CH4 adsorption at the O atop site of (Fe2O3)4 with an adsorption energy of 35.1 kJ mol−1. When n increases from 4 to 60, the Fe atop adsorption becomes weaker with 43.9 kJ mol−1 lower adsorption energy. However, the adsorption at the Fe atop site and the O atop site of (Fe2O3)60 nanoparticles is still stronger than adsorption on Fe2O3 (001) surface, as shown in Fig. 5. This is because the average coordination number of surface Fe atoms in (Fe2O3)n nanoparticle is smaller than that on Fe2O3 (001) surface. The undercoordination results in an upward shift of the Fe d-band, yielding high binding energies.

In chemical looping partial oxidation process, CH4 is initially dissociated over oxygen carriers to form hydrogen and CHx radicals. Then the CHx radicals are oxidized by lattice oxygen to generate CO or CO24,22. Since the energy and geometry of CH4 adsorption on (Fe2O3)20 are similar with CH4 adsorption on (Fe2O3)60, Fe40O60 (n = 20) nanoparticles are chosen as the model to calculate the reaction barriers of CH4 dissociation and oxidation. The energy profile was mapped out as shown in Fig. 5. The energy barrier for the first step of CH4 dissociation on Fe40O60 is 135.8 kJ mol−1, which is 55.7 kJ mol−1 lower than that of CH4 dissociation on the Fe2O3 (001) surface. Fe40O60 also exhibit higher activity for CH3, CH2, and CH dissociation due to the lower barriers, compared with the Fe2O3 (001) surface. It indicates that nanostructured Fe2O3 facilitates CH4 conversion compared with bulk Fe2O3, which is in good agreement with TGA and fixed bed test. After methane dissociation, all C–H bonds are cleaved to generate a carbon atom and four hydrogen atoms. Fe40O60 has three chemically distinguishable types of lattice oxygen atoms: 2-fold coordinated lattice oxygen O2C, 3-fold coordinated lattice oxygen O3C, and 4-fold coordinated lattice oxygen Osub. As such, there are three reaction pathways for CO formation as shown in Supplementary Fig. 8. The calculated barriers for CO2C, CO3C, and COsub formation are 37.2 kJ mol−1, 69.6 kJ mol−1, and 58.5 kJ mol−1, respectively. This result indicates C binding to O2C is the most favorable path, compared with C binding to O3C and Osub because Fe–O bonds of low-coordinated lattice oxygen atoms are easier to break than high-coordinated lattice oxygen atoms. In contrast to Fe40O60, all lattice oxygen atoms in the topmost atomic layer of the Fe2O3 (001) surface are three-coordinated atoms. Thus, the carbon atom on the Fe2O3 (001) surface converts to CO only via binding to O3C, leading to a relatively high barrier of 61.2 kJ mol−1 as shown in Fig. 5.

The formed CO may further react with surface lattice O atoms to form CO221,22. For the Fe40O60 nanoparticle, the formation of CO2 needs to overcome a barrier of 148.9 kJ mol−1, which is 30.4 kJ mol−1 higher than that of CO2 formation on Fe2O3 (001) surface. The high barrier with respect to CO2 formation on Fe40O60 is attributed to the surface stress of nanoparticles, induced by surface atoms with unsaturated coordination. The surface stress leads to shorter and thus stronger Fe–O3C bonds compared with Fe–O3C bonds of the Fe2O3 (001) surface. The formation of CO2 on Fe40O60 is endothermic, with the calculated reaction energy of 58.2 kJ mol−1. These results indicate that the CO2 formation on Fe40O60 is both kinetically and thermochemically unfavorable. Therefore, Fe40O60 nanoparticles significantly promote CO formation while inhibiting CO2 production. Unfortunately, DFT-based calculations of large nanoparticles consisting of a few thousand atoms, required for confirming this conclusion, are intractable to compute even on the most powerful supercomputers. Nevertheless, the experimental evidence for the extraordinary CO selectivity of Fe2O3 nanoparticles with the size of 5 ± 3 nm indicates that nanostructuring makes Fe2O3 a more active oxide for CO production compared with bulk Fe2O3.

Discussion

In summary, we demonstrate that Fe2O3@SBA-15 enables near 100% CO selectivity in chemical looping methane partial oxidation, which is so far the highest value in product selectivity observed for chemical looping systems. Moreover, the effective temperature for syngas generation is lowered to 750–935 °C, which is over 100 °C lower than current state-of-the-art processes. Nanoscaled oxygen carriers are presented to exhibit little high-temperature reactivity property deterioration and adaptability to broader temperature operating windows for chemical looping operation conditions. These are important factors that can contribute to significant energy-saving reactor designs. The theoretical model and calculations reveal that the structure of the nanoparticles play a key role in CO selectivity enhancement of Fe2O3@SBA-15. The CH4 adsorption energies and CO formation barriers depend not only on the nanoparticle size but also on the type of surface site exhibited by the nanoparticles. The small average coordination number of Fe atoms in the nanoparticle facilitates CH4 adsorption and activation due to an upward shift of the Fe d-band, while the low-coordinated O atoms greatly promote Fe–O bond cleavage and CO formation, leading to a significant increase in CO selectivity. These findings contribute to a nanoscale understanding of the underlying metal oxide redox chemistry for chemical looping processes, and provide a systematic strategy toward the design of robust oxygen carrier nanoparticles with superior activity and selectivity.

Methods

Sample preparation

Surfactant CTAB and Fe(NO3)3·9H2O were dissolved in 120 mL ethanol. 0.4 g SBA-15 was stirred in the solution for overnight at room temperature. This is followed by a powderization at 90 °C, and then calcination at 600 °C for 5 h. The prepared sample is marked as Fe2O3@SBA-15. Fe2O3 particles without SBA-15 support was also prepared by the same method. For Fe2O3@SAB-15, the volume loading was calculated by Eq. (1):

where \(m_{{\mathrm{Fe}}_2{\mathrm{O}}_3}\) is the total weight of Fe2O3, mSBA-15 is total weight of SBA-15, \({\uprho} _{{\mathrm{Fe}}_2{\mathrm{O}}_3}\) is density of Fe2O3.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA)

The selectivity of Fe2O3@SBA-15 was tested in a SETARAM thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) device. A 20 mg sample was mounted in the TGA, and heated from 750 °C to 935 °C with a temperature ramp of 10 °C/min. 20 mL/min of CH4 balanced with 180 mL/min of He was used in the partial oxidation. The outlet gas composition was analyzed by mass spectrometry (MS). 75 redox cycles were also conducted on both samples to test their recyclability. During the methane partial oxidation, 50 mL/min of CH4 balanced with 100 mL/min of N2 and 50 mL/min of He carrier gases was used in a TGA to react with the sample for 5 min. For the regeneration, 100 mL/min of air balanced with 100 mL/min of N2 was used to oxidize the sample for 5 min. Between the reduction and the oxidation, 100 mL/min of N2 was used as the flushing gas to prevent the mixing of air and methane.

Fixed bed experiment

The methane conversion and syngas selectivity of both unsupported Fe2O3 and Fe2O3@SBA-15 were also evaluated in a quartz U-tube (1 cm diameter) fixed bed reactor. Four different methane weight hourly space velocity (WHSV) of 17.8, 25, 30, 37.5 mL (\({\mathrm{mg}}_{{\mathrm{Fe}}_2{\mathrm{O}}_3}\) h)−1 were applied to each sample. In the experiment, the solid were amounted in the center of the reactor that is placed in a tube furnace and heated to 800 °C. The outlet gas was analyzed by MS.

Computational details

All plane-wave DFT calculations were performed using the projector augmented wave pseudopotentials provided in the VASP. The Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof exchange-correlation functional was used with a plane-wave expansion cutoff of 400 eV23. Due to the valence electrons of Fe 3d state, the Hubbard U approach was used to correct self-interaction errors of α-Fe2O324,25. The increase of U from 1 to 4 eV results in better agreement with the density of states by experimental inverse photoemission spectra26. However, a further increase in U will cause Fe 3d states to shift to unacceptably low energies. Therefore, U = 4 eV was chosen to describe the energy required for adding an extra d electron to the Fe atom. Geometry optimization of the nanoparticle was carried out at the Γ-point. All atoms were allowed to relax until the ionic forces are smaller than |0.01| eV Å−1, with a total energy threshold determining the self-consistency of the electron density of 1.0 × 10−5 eV atom−1. Dispersion interactions are modeled using the DFT-D3 method developed by Grimme et al.27,28. The calculated α-Fe2O3 bulk lattice parameters were a = b = 5.04 Å and c = 13.83 Å, in good agreement with the experimental values (a = b = 5.038 Å and c = 13.772 Å). The α-Fe2O3 (001) surface with Fe-O3-Fe- termination was chosen to model the iron oxide slab with a thickness of ~15 Å29. Fe2O3 nanoparticles were modeled by a three-dimensional periodic arrangement with a large cubic cell of 5 × 5 × 5 nm3 to minimize lateral interactions. The structures of the free nanoparticles (Fe2O3)n (n = 4–60) were fully optimized without any symmetry constraints. The climbing-image nudged elastic band method30,31 is used to locate transition states of elementary steps and map out reaction pathways for CH4 dissociation and oxidation on the Fe2O3 nanoparticles. The effect of temperature (800 °C) was taken into account for adsorption and reaction barrier comparison.

Characterization methods

The scanning electron microscope measurements were performed with FEI Helios Nanolab 600, with the voltage of 10 kV and the current of 0.17 mA. The TEM images were obtained with a FEI Tecnai G2 30 at 300 kV.

The surface area of the sample was analyzed by NOVA 4200e. The sample was first degassed at 300 °C for over 10 h. Then isothermal N2 adsorption was performed at −196 °C. The surface area of both SBA-15 and Fe2O3@SBA-15 was determined by Brunauer–Emmett–Teller method, while the pore size distribution was calculated by Brunauer–Joyner–Halenda method32 with adsorption branch.

Small-angle X-ray diffraction was conducted with Rigaku SmartLab equipped with Cu K-α radiant. Data were collected from 0.7° to 3° with a scanning rate of 0.1° per minute.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Luo, S. et al. Shale gas-to-syngas chemical looping process for stable shale gas conversion to high purity syngas with a H2:CO ratio of 2:1. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 4104–4117 (2014).

Fan, L.-S., Zeng, L. & Luo, S. Chemical‐looping technology platform. AIChE J. 61, 2–22 (2015).

Qin, L. et al. Enhanced methane monversion in mhemical looping partial oxidation systems using a copper doping modification. Appl. Catal. B 235, 143–149 (2018).

Zeng, L., Cheng, Z., Fan, J. A., Fan, L.-S. & Gong, J. Metal oxide redox chemistry for chemical looping processe. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2, 349–364 (2018).

Fan, L.-S. Chemical Looping Partial Oxidation: Gasification, Reforming, and Chemical Syntheses, (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

Chung, C., Qin, L., Shah, V. & Fan, L.-S. Chemically and physically robust, commercially-viable iron-based composite oxygen carriers sustainable over 3000 redox cycles at high temperatures for chemical looping applications. Energy Environ. Sci. 10, 2318–2323 (2017).

Sun, Z., Ma, T., Tao, H., Fan, Q. & Han, B. Review: fundamentals and challenges of electrochemical CO2 reduction using two-dimensional materials. Chem 3, 560–587 (2017).

Alalwan, H. A., Mason, S. E., Grassian, V. H. & Cwiertny, D. M. α-Fe2O3 nanoparticles as oxygen carriers for chemical looping combustion: an integrated materials characterization approach to understanding oxygen carrier performance, reduction mechanism, and particle size effects. Energy Fuels 32, 7959–7970 (2018).

Coleman, N. R. et al. Synthesis and characterization of dimensionally ordered semiconductor nanowires within mesoporous silica. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 7010–7016 (2001).

Burke, A. M. et al. Large pore bi-functionalised mesoporous silica for metal ion pollution treatment. J. Hazard. Mater. 164, 229–234 (2009).

Delaney, P. et al. Development of chemically engineered porous metal oxides for phosphate removal. J. Hazard. Mater. 185, 382–391 (2011).

Delaney, P. et al. Porous silica spheres as indoor air pollutant scavengers. J. Environ. Monit. 12, 2244–2251 (2010).

Barreca, D. et al. Methanolysis of styrene oxide catalysed by a highly efficient zirconium-doped mesoporous silica. Appl. Catal. A 304, 14–20 (2006).

Ahern, R. J., Hanrahan, J. P., Tobin, J. M., Ryan, K. B. & Crean, A. M. Comparison of fenofibratemesoporous silica drug-loading processes for enhanced drug delivery. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 50, 400–409 (2013).

Abdallah, N. H. et al. Comparison of mesoporous silicate supports for the immobilisation and activity of cytochrome c and lipase. J. Mol. Catal. B: Enzym. 108, 82–88 (2014).

Flynn, E. J., Keane, D. A., Tabari, P. M. & Morris, M. A. Pervaporation performance enhancement through the incorporation of mesoporous silica spheres into PVA membranes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 118, 73–80 (2013).

Kumar, A. et al. Direct air capture of CO2 by physisorbent materials. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 54, 14372–14377 (2015).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558 (1993).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169 (1996).

Cheng, Z., Qin, L., Guo, M., Fan, J. A. & Fan, L.-S. Methane adsorption and dissociation on iron oxide oxygen carrier: role of oxygen vacancy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 16423–16435 (2016).

Cheng, Z. et al. Oxygen vacancy promoted methane partial oxidation over iron oxide oxygen carrier in chemical looping process. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 32418–32428 (2016).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865 (1996).

Herbst, J., Watson, R. & Wilkins, J. Relativistic calculations of 4f excitation energies in the rare-earth metals: further results. Phys. Rev. B 17, 3089 (1978).

Anisimov, V. & Gunnarsson, O. Density-functional calculation of effective Coulomb interactions in metals. Phys. Rev. B 43, 7570 (1991).

Rollmann, G., Rohrbach, A., Entel, P. & Hafner, J. First-principles calculation of the structure and magnetic phases of hematite. Phys. Rev. B 69, 165107 (2004).

Grimme, S., Antony, J., Ehrlich, S. & Krieg, H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 19 (2010).

Grimme, S., Ehrlich, S. & Goerigk, L. Effect of the damping function in dispersion corrected density functional theory. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1456–1465 (2011).

Qin, L., Cheng, Z., Guo, M., Fan, J. A. & Fan, L.-S. The impact of 1% lanthanum dopant oncarbonaceous fuel redox reaction with iron based oxygen carrier in chemical looping processes. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 70–74 (2017).

Sheppard, D. & Henkelman, G. Paths to which the nudged elastic band converges. J. Comput. Chem. 32, 1769–1771 (2011).

Henkelman, G., Uberuaga, B. P. & Jónsson, H. Climbing image nudged elastic band method for finding saddle points and minimum energy paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 9901–9904 (2000).

Li, B. & Zhang, S. Methane reforming with CO2 using nickel catalysts supported on yttria-doped SBA-15 mesoporous materials via sol–gel process. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 38, 14250–14260 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The service support provided by the Center for Electron Microscopy and the Analysis and NanoSystem Laboratory at The Ohio State University and the computing support provided by the Ohio Supercomputer Center are gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L. performed TEM, SEM, EDX, TGA redox experiments, TPR, and fixed bed experiments. L.Q. designed the experiments. Y.L., L.Q., J.W.G., and F.K. analyzed data. Z.C. performed the DFT calculation and analyzed the mechanism. J.W.G. did the sample synthesis and surface and pore size analysis. F.K. performed SAXRD experiments. J.A.F. discussed the results and commented on the manuscript. L.S.F. supervised the research. All authors participated in manuscript preparation, data interpretation and discussions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Qin, L., Cheng, Z. et al. Near 100% CO selectivity in nanoscaled iron-based oxygen carriers for chemical looping methane partial oxidation. Nat Commun 10, 5503 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13560-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13560-0

This article is cited by

-

The Effect of Mn/Fe Ratio on the Oxygenates Distribution from Partial Oxidation of n-C5H12 by Plasma Catalysis Over FeMn/Al2O3 Catalyst

Plasma Chemistry and Plasma Processing (2024)

-

Performance assessment of novel nanofibrous Fe2O3/Al2O3 oxygen carriers for chemical looping combustion of gaseous fuel

Chemical Papers (2024)

-

Coupling acid catalysis and selective oxidation over MoO3-Fe2O3 for chemical looping oxidative dehydrogenation of propane

Nature Communications (2023)

-

Biogas conversion to liquid fuels via chemical looping single reactor system with CO2 utilization

Discover Chemical Engineering (2023)

-

Selective catalytic oxidation of ammonia to nitric oxide via chemical looping

Nature Communications (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.