Abstract

After permanent atmospheric oxygenation, anomalous sulfur isotope compositions were lost from sedimentary rocks, demonstrating that atmospheric chemistry ceded its control of Earth’s surficial sulfur cycle to weathering. However, mixed signals of anoxia and oxygenation in the sulfur isotope record between 2.5 to 2.3 billion years (Ga) ago require independent clarification, for example via oxygen isotopes in sulfate. Here we show <2.31 Ga sedimentary barium sulfates (barites) from the Turee Creek Basin, W. Australia with positive sulfur isotope anomalies of ∆33S up to + 1.55‰ and low δ18O down to −19.5‰. The unequivocal origin of this combination of signals is sulfide oxidation in meteoric water. Geochemical and sedimentary evidence suggests that these S-isotope anomalies were transferred from the paleo-continent under an oxygenated atmosphere. Our findings indicate that incipient oxidative continental weathering, ca. 2.8–2.5 Ga or earlier, may be diagnosed with such a combination of low δ18O and high ∆33S in sulfates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Today, Earth’s oxygen-rich (21% O2 by volume) atmosphere drives a marine sulfur cycle dominated by oxidative weathering. Rivers supply the ocean with substantial loads of dissolved sulfate (SO42−) derived from the oxidation of pyrite and the dissolution of sulfate minerals in roughly equal proportions1. Within marine and terrestrial settings, microbial sulfate reduction (MSR) processes exert the most important controls on sulfur isotopic fractionation of SO42−. During MSR, the partial reduction of SO42− preferentially converts 32S to sulfide that is mostly re-oxidised, whereas a fraction of the sulfide product is retained within iron sulfide minerals2. Because of mass-dependent sulfur fractionations from MSR, marine sulfide has a large, but relatively 34S-depleted, range in δ34S (see Methods for isotope notations) and a ∆36S/∆33S slope of approximately −93. Simultaneously, marine SO42− is concentrated at 28 mM, enriched in 34S (δ34S = 21‰4;, and has a small 33S enrichment (∆33S < 0.1‰).

In contrast, before atmospheric oxygenation sufficiently drove the oxidation of sulfur at the Earth's surface, the surface sulfur cycle was first controlled by atmospheric inputs of sulfur that can be traced within Archaean age, 4.0–2.5 Ga, sedimentary rocks displaying strong sulfur mass independent fractionation (S-MIF) in their ∆33S values between +14‰ and −45,6,7 (Fig. 1a). There are lingering geochemical8 and quantitative9 challenges still to be understood about the preservation and generation of Archaean S-MIF signals. However, it is generally accepted that S-MIF results from atmospheric photochemical reactions operating under low O2 of <0.001% of the present atmospheric level (PAL) of oxygen, causing surface sulfur fluxes of insoluble S0 with ∆33S > 0‰ and soluble SO42− with ∆33S < 0‰ that were not homogenised during their transfer into sedimentary rocks10,11.

Kazput Formation barite sulfur and oxygen isotope data from this study are shown alongside compilations of time series data and temporal estimates of sulfur fluxes and atmospheric O2. In further detail, shown are a pyrite and sulfate ∆33S data, b δ18O data of sedimentary carbonate, chert, shale, and sulfate and c the evolution of O2 showing maximum ranges67 with ratios of sulfur influxes to the ocean of total versus present day and weathering versus total flux61. The shaded regions represent intervals of glaciations of possibly global significance. The Turee Creek pyrite data in a are from16, and Kazput carbonate data in b are from33. Data sources and details are provided in Supplementary Note 1, while source data are provided in a Source Data file

The disappearance of anomalous ∆33S signals from the sedimentary record is a crucial constraint on the rise of oxygen around the Archaean-Proterozoic boundary, but despite intensive efforts its exact timing remains unclear. This transition is constrained in continuous stratigraphic section only in S. Africa, within three different age-equivalent cores from the Transvaal Basin. There, ∆33S decreases below 0.4‰ between 2316 and 2326 ± 7 million years (Ma) ago, a horizon that has been interpreted as the shift to >0.001% PAL of oxygen and considered by some as the Great Oxidation Event (GOE) itself6,12,13. Alternatively, the slow disappearance of ∆33S signals from the rock record after 2.45 Ga may be attributable to the increasingly important oxidative weathering of an older, S-MIF-bearing, continental sulfide reservoir whose anomalous isotope compositions (i.e., ∆33S > 0.4‰) would be transferred to sulfate until this source was either exhausted or negligible as compared to contemporaneous, non-anomalous, sulfur sources14. Subsequent evidence has supported15,16 and challenged17 this assertion. Because all of these studies interpret the record of S-MIF directly, independent tests are needed to delineate the importance of atmospheric and weathering controls on the early surficial sulfur cycle.

The sparse sulfate record during the Archaean Eon, and into the early Palaeoproterozoic, has prevented a closer examination of the oxidative side of Earth's early sulfur cycle. Evaporites and bedded barites are discontinuous, while more continuous records are hindered by weakly concentrated carbonate-associated sulfates (CAS) that are vulnerable to contamination18, diagenetic alteration19 and loss during metamorphic recrystallization20. Furthermore, as CAS concentrations should approximate ambient seawater SO42− concentrations, low early Earth seawater sulfate can challenge the recovery of measurable CAS. For example, between 2.5 and 2.3 Ga, it can be difficult to obtain sufficient CAS from sediments for sulfur isotope measurements, where up to 1500 grams of carbonate may be necessary6. Such low CAS yields, being especially vulnerable to contamination and overprinting, may discourage the additional measurement of oxygen isotopes.

Here, to investigate the influence of early Earth sulfide weathering, we focus on barite (BaSO4), a highly insoluble and diagenesis-resistant mineral that offers a robust record of sulfate S and O isotope compositions21. The majority (70–92%22) of oxygen atoms incorporated in sulfide-derived SO42− are contributed by ambient water at the locus of oxidation (e.g., δ18O values of present-day seawater ≈ 0‰, meteoric waters ≈ 0‰ to −20‰, snow and ice ≈ −20‰ to −60‰23), with a lesser contribution from other oxidants such as O2, followed by negligible isotopic exchange24. For example, sulfates in sediments are normally enriched in 18O versus their water oxygen source, where seawater at δ18O ≈ 0‰, or lower25, results in marine SO42− being ≥6‰ through time (Fig. 1b). Meanwhile, MSR leaves a diagnostic positive correlation between the δ34S and δ18O of affected sulfate26. Thus, after its formation, the relatively conservative behavior of SO42− may permit discrimination between its different environmental origins and transformations.

The 2.45 Ga27,28 to 2.2 Ga29 Turee Creek Group sedimentary succession from W. Australia is ideal for seeking barite records to characterize the response of the surface sulfur cycle around the time of atmospheric oxygenation. Here we report Turee Creek Group barites with positive ∆33S values and distinctly negative δ18O values whose paleoenvironmental and temporal context suggest a first-order weathering control, mediated by biologically enhanced preservation, on their anomalous sulfur isotope signals ca. 2.3 Ga.

Results and discussion

S- and O- isotopic signatures from Turee Creek barites

All of our barites register signals of S-MIF, featuring ∆33S values from +0.62‰ to +1.55‰ and ∆36S/∆33S ratios falling within −0.9 to −1.5‰ (Figs. 2, 3, Supplementary Table 1). The δ18O values span + 2.2‰ to −19.5‰, with an average of −11.0‰ (VSMOW). The sulfur δ34S, ∆33S and ∆36S and oxygen δ18O measurements are obtained from trace barites of the lower Kazput Formation that were chemically extracted from drill core 3 of the Turee Creek Drilling Project (TCDP3) (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). Although barites were observed in acid-digested residues, the grains were too small (<3 μm) to be identified via standard transmitted light microscopy, and thus only imaged via SEM (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4).

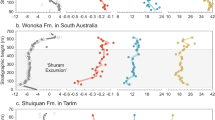

The stratigraphic distribution of barite stable isotope data (δ34S, ∆33S, ∆36S and δ18O), carbonate abundance (wt. % carb.), total sulfur (wt. % S), and Fe/Al mass ratios are plotted by their depth in drill core TCDP3 of the lowermost Kazput Formation. Pyrite isotope and weight percent sulfur data are from16, while Fe/Al mass ratios are from31. Isotope data analytical uncertainties (2σ) are ± 0.1‰, ± 0.01‰, ± 0.2‰ and ± 0.4‰ for δ34S, ∆33S, ∆36S and δ18O, respectively, and are shown as error bars or are smaller than the symbols. The ARA on the ∆36S/∆33S plot is the Archaean Reference Array, as in Fig. 3. The filled symbols are from the core depth interval 112–135 m with specific sulfur-oxygen isotope correlations that are discussed in the text and shown in Fig. 3. Figure source data are included in the Source Data file

sulfur and oxygen isotope systematics of barite data are shown from the Kazput Formation carbonate. The two left-hand plots, a, b show only sulfur data, while c, d show both oxygen and sulfur data. Analytical uncertainties are the same as in Fig. 2. ARA: Archaean Reference Array;68 pyrite avg. MBM: average isotope composition of pyrite from the Meteorite Bore Member diamictite16. The ARA describes quadruple sulfur isotope correlations during the Archaean attributed to mass independent processes, where Δ33S = 0.9 × δ34S, and Δ36S = −0.9 or −1.5 × Δ33S68. See Methods for isotope notation definitions and the Source Data file for data

Geological and geochemical context

The analysed barites are from the Kazput Formation of the Turee Creek Group, an overall-shallowing succession with Mn-enriched units and decreasing iron contents that have been interpreted in favor of increasing atmospheric oxygen30. Recently reported nitrogen isotope and iron speciation evidence from the Kazput Formation further indicates free oxygen availability during its deposition31. An age of 2.25 Ga was assigned, as based on detrital zircon U-Pb dating and estimated sedimentation rates28. While this age may be appropriate, in order to be conservative with respect to what may be a remarkably young record of isotopically anomalous sulfur, here we simply assume that the Kazput Formation is younger than 2.31 Ga, the age constraint from the lower Meteorite Bore Member diamictite16. Isotope compositions of Kazput Formation carbonates are δ13C = −2‰ to + 1.5‰ and δ18O = −16.63‰ to −8.13‰ (VPDB), suggesting that diagenesis has not erased their record of primary seawater chemistry32. Geologic maps locating the TCDP cores (Supplementary Fig. 1), core photographs (Supplementary Fig. 2), and transmitted light photomicrographs with complementary XRF analyses (Supplementary Figs. 5, 6) are provided in the Supplementary Information. The lower Kazput contains finely laminated mud- and silt-stones that shallow into laterally variable oolitic and stromatolitic carbonates with deltaic influence32. Our examined carbonates are fine-grained with mm- to cm-scale laminations, resembling facies association A of Barlow and co-authors33, who further described local occurrences of dome-shaped stromatolites. The carbonate horizon gradates into, and out of, finely cross-laminated carbonate-rich siltstones (Fig. 2).

The strong 18O-depletion of the Kazput barites appear consistent with sulfide-derived SO42− being the carrier of S-MIF signals to the W. Australia sedimentary record after 2.31 Ga. Such low δ18O values in sulfates are only known from terrestrial settings (e.g., glacial, high latitude, or lacustrine) (Fig. 1b) that have distinctly 18O-depleted water sources23. The significant S-MIF of the barite that falls within the Archaean ∆36S/∆33S array (ARA, Fig. 3a) suggests that the sulfur source was originally fractionated in an atmosphere containing <0.001% PAL oxygen. Importantly, the barite S isotope compositions closely overlap with those of previously reported early diagenetic pyrites in the same TCDP3 core (Fig. 2), which implies that the sulfur precursor was mostly unmodified during its conversion to reduced (sulfide) or oxidised (sulfate) mineral phases, or that one phase was derived from the other without isotopic fractionation. Because, under various conditions, it is possible for low temperature redox reactions to proceed without S-isotope fractionation between sulfate and reduced sulfur phases34, by itself, the S-isotope match between Kazput barite and pyrite cannot be used to diagnose a specific process. Broadly, however, the S-MIF in Kazput barite requires an atmospheric sulfur source that originated under an atmosphere with <0.001% PAL O2, occurring within one of two scenarios: either the capture of such atmospheric sulfur under an essentially oxygen-free atmosphere existing at <2.31 Ga, or the reworking/recycling of an archival atmospheric sulfur source that was generated any time before 2.31 Ga. Understanding how and when these barites inherited their atmospherically derived sulfur is of fundamental importance to understanding Earth’s oxygenation and its imprints on the minor sulfur isotope record.

Assessing the origin of Kazput barite

Given that pyrite-derived SO42− can closely match the sulfur isotope composition of its pyrite precursor under abiotic or biologically mediated oxidation34,35, the nearly identical δ34S (and ∆33S) compositions of Kazput barite and pyrite could be attributed to low temperature pyrite oxidation during sample preparation in the laboratory. While pyrite oxidation produces dissolved SO42− as its immediate product, barite formation further requires the capture of SO42− with barium, which makes it more difficult to accidentally produce in the lab during sample handling. This requirement is important because fluids can be concentrated in barium or SO42−, but not both, due to barite's low solubility36. We performed extensive tests of pyrite oxidation during barite extraction, as well as during attempted extractions of CAS, where pyrite oxidation during sample processing was excluded (see Methods).

A metamorphic origin for the barite must also be considered, as it could explain the occurrence of their S-MIF signals, irrespective of the host rock's age. For example, post-depositional metamorphic processes have been implicated in the remobilization and dilution of S-MIF signals in sulfur from N. American Palaeoproterozoic Huronian sections37. The metamorphism of the Turee Creek Group is constrained to prehnite-pumpellyite–epidote facies up to 300 °C38. Additional constraint from a SIMS study on the Turee Creek Group yields a maximum metamorphic temperature of 240 °C that was estimated from sharp sulfur isotope gradients of δ34S ranging over 30‰ across a <4 µm transect in pyrite39. More importantly, previous work on trace element abundances in pyrites from TCDP drill cores has demonstrated the early diagenetic origin of their sulfur16. Considering the S isotope match between the Kazput barite and pyrite, we conclude that the barites are, likewise, of low temperature origin without significant metamorphic alteration.

A detrital origin for Kazput barites could provide another explanation for the unexpected young age, <2.31 Ga, of their sulfur isotope anomalies. Evidence for an anoxic atmosphere that is found in sedimentary rocks are rounded detrital grains of pyrite and uraninite that were not dissolved during riverine transport due to low oxygen availability40. The pyrite in the Kazput Formation is not detrital, and instead appears to have grown in situ. Kazput pyrites occur as microcrystalline aggregates, euhedral crystals, and elongated layer-parallel concretions in a range of sizes (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6). In contrast, sedimentary reworking of Kazput barites is difficult to ascertain due to the barite size, <10 μm, and disseminated occurrence (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4), but they share a tight S-isotopic match with the co-occurring diagenetic pyrites. Therefore, the mutual sulfur source for the barite and pyrite, despite different mode of occurrence, also excludes a detrital origin for the barite.

Secondary oxidation of pyrite to SO42− could occur at low temperature within the rock during its burial history, for example, via pyrite oxidation by pore waters. Firstly, it is feasible to oxidize pyrite under anoxic conditions via radiolysis of water that is accompanied by an enrichment of 1.5–3.4‰ in the δ34S values of SO42− versus pyrite41, but this scenario is ruled out because Kazput barite does not show such S-isotope enrichment versus the previously reported pyrite (Fig. 2). Meanwhile, if late oxidation by infiltrating fluids occurred, then carbonate, which is very susceptible to diagenetic alteration of its oxygen isotope composition42, should register alteration by the same 18O-depleted waters implicated in the oxidation of pyrite to form the barite. Instead, comparison of δ18O data from Kazput carbonate with our barite reveals separate environments of formation for the carbonate and SO42−. The Kazput carbonate has an average δ18Ocarb = 18.4‰ (here converted to the VSMOW scale)33 that is typical for marine carbonates of similar age, but 10‰ lower than present-day marine carbonates (Fig. 1b). As reviewed by Gomes and Johnston34, the oxygen isotope fractionation between pyrite-derived SO42− and water spans a range of δ18O values between 0‰ and +20‰ for naturally relevant conditions. Oxidation experiments using waters with δ18O compositions >15‰ have produced sulfide-derived sulfates that have very low δ18O compositions versus their source waters, as exemplified by an extreme case of −65‰ fractionation between pyrite-derived sulfate (+71‰) oxidised in isotopically labeled water (+127‰)43. Although the topic of sulfate oxygen isotope fractionation demands clarification, we contend that Kazput barites are well within the range of δ18O values, below 15‰, of natural sulfates that are 18O-enriched versus their water oxidant sources. Regardless of assumptions concerning sulfate-water oxygen isotope fractionations, distinct water–oxygen sources are required to produce sulfate δ18O compositions that are appreciably lower than those of coeval carbonates. These low sulfate compositions are apparent in non-marine sulfates as compared to concurrent marine carbonates at ca. 0.0, 0.6 and 1.4 Ga (Fig. 1b). Similarly, relative to coeval Kazput carbonates, the low δ18O values of our barites require a meteoric-water–oxygen source.

A unique combination of environmental conditions likely contributed to the isotopic signatures of Kazput barite, but perhaps they were also preserved due to the sulfuretum, or consortium of sulfur-metabolising microbiota, active in the Turee Creek Basin during the Palaeoproterozoic. Besides prevalent microbial mats in the Kazput carbonate, it also contains microfossils that have been interpreted as sulfur-oxidizing filamentous bacteria44. What is remarkable about such bacteria from an isotopic perspective is that a sulfuretum of SO42−-reducing microbes and sulfur-oxidizing bacteria can produce sulfide that gets re-oxidized to SO42−, via elemental sulfur, with no net S isotope fractionation45. Sulfur-oxidizing bacteria may have contributed to the Kazput barites' oxygen isotope signals, perhaps by introducing Turee Creek Basinal water–oxygen to the SO42− produced during re-oxidation of MSR-produced sulfide, or by enhancing rates of sulfide oxidation on land. An MSR influence can be indicated by positive δ18O–δ34S correlation in sulfate46, however, the negative correlations between Kazput barite δ18O and its sulfur isotope parameters (Fig. 3c, d) imply that source mixing, with sulfide weathering in meteoric waters, was much more important than MSR for setting these S and O isotope signatures. As the source-controlled barite sulfur and oxygen isotope variations mask microbial influence, further speculation about the biological role in Turee Creek sulfur cycling remains open.

A continental source of isotopically light oxygen

We suggest, given the previous evidence that has ruled out post-depositional processes and a detrital origin while pointing to a meteoric water oxygen source, that the O isotope signals preserved in Kazput barite are best explained by pyrite oxidation on land. Kazput barite δ18O, extending to −19.5‰, are among the lowest values in the sedimentary record, including other sulfate occurrences going down to −20.3‰ from a Neoproterozoic snowball Earth glacial diamictite deposited at 635 Ma47, and in relatively more recent terrestrial deposits from within the Arctic Circle that reach down to −19.7‰22 (Fig. 1b). Similarly, the range of oxygen isotope compositions of Kazput barite may require a glacial meltwater oxidant source. However, in contrast to those other examples of very low δ18O in sulfate, Kazput barite δ18O may not necessitate glacial or ice meltwater oxygen sources, and instead could reflect a hydrosphere anchored to seawater with a lower δ18O than today. Meteoric waters evolve lower δ18O compositions than seawater due to evaporation from seawater followed by Rayleigh distillation in cooling air masses23. The most evolved meteoric waters (and snow and ice melt) that can be found at high latitudes, high elevations and away from coastlines are marked by the lowest δ18O compositions relative to seawater. This relative relationship between seawater and more 18O-depleted meteoric waters is significant here, as it has been suggested that the δ18O of seawater (0‰ at present23) may have changed through time, perhaps being as low as −10‰ in the Archaean25. Newly reported iron oxide δ18O records, which are insensitive to temperature, convincingly support that seawater was lower in the past, having a δ18O at near −8‰ by around 2.0 Ga48. Palaeoproterozoic seawater appears to be faithfully recorded in Kazput carbonate that is, as mentioned previously, on the order of 10‰ lower than modern carbonates but comparable to carbonates from around 2.3 Ga. Therefore, the Kazput barites recording the lowest δ18O indicate their precursor sulfate was oxidised in the most evolved meteoric waters, placing this water–oxygen source for this sulfate firmly on land, as compared to a seawater δ18O that was likely around −10‰. Although sulfate-water oxygen isotope fractionation during sulfide oxidation requires further study, we take a median sulfide-derived sulfate-water δ18O fractionation value of +10‰34, as compared to the barite, to roughly estimate that the water sources for Kazput sulfate may have ranged between −30‰ and −8‰. Considering a possible seawater composition around −10‰, this range of source water δ18O is appropriate for meteoric sources. Alternately, if ca. 2.3 Ga seawater resembled a contemporary δ18O composition, the estimated range of water δ18O overlaps seawater while extending from meteoric to glacial waters. Regardless, the association between low δ18O and high ∆33S in the Kazput barites implicates continental weathering of sedimentary sulfides as the vector carrying S-MIF to the Turee Creek Basin.

A model of Kazput barite formation

Taken together, the S- and O-isotope systematics suggest a singular scenario for the origin of the Kazput barite. The barite and pyrite ∆33S values reach a maximum in the studied drill core as compared to the two other Turee Creek Group drill cores in older underlying sediments16. The strongest expression of this sulfur source appears with maxima of ∆33S and δ34S coincident with the δ18O minimum in barite, where negative correlations between δ18O and ∆33S and δ34S data exist between 112 and 135 metre depth within the center of the carbonate unit (Fig. 3c, d). Such S–O isotope correlation may indicate the mixing of sulfide-derived SO42− sources with distinct S-isotope compositions but overlapping δ18O ranges due to their oxidation in meteoric waters under variable humidity, as is observed in major river systems today49,50. The preservation of such a strongly riverine sulfate signal in marine sedimentary rocks is unlikely today due to buffering by high contemporary seawater sulfate concentrations. A previously identified source of sulfur in the Turee Creek Basin with a monotonous ∆33S ≈ 0.9‰ is well expressed in the Meteorite Bore Member diamictite16. Mixing between this monotonous sulfur source and a different, continental-weathering, source with a higher ∆33S ≈ 1.6‰ is observed in S–O isotope space (Fig. 3c). The first-order controls on the mix of sulfur sources are relative sea level and the exposure of sedimentary rocks to weathering. Minimal overprinting resulted in a largely faithful transfer of S- and O-isotope signatures as sulfate was captured as barite or reduced to form pyrite (0.32 weight % on average, Supplementary Table 2). Anoxic sediment porewaters favoring MSR would provide a flux of barium in sufficient concentration to precipitate SO42− as barite at the sediment-water interface51. Remaining porewater SO42− would be quantitatively reduced to sulfide, via closed system MSR, with capture by iron to form iron sulfides (pyrites) during early diagenesis in the sediment16. This is consistent with the lack of CAS-sulfate from the Kazput carbonate that supports near-quantitative reduction of SO42− in porewaters. Previously reported Fe/Al mass ratios in core TCDP3 and the Kazput carbonate are 0.64 on average, excluding enriched intervals >1 (Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 3). The Fe/Al and total sulfur enrichments imply either transient water column anoxia, or movement of a chemocline during transgression-regression cycles that could in turn represent enhanced sulfate fluxes from land and their drawdown into anoxic sediments via microbial sulfate reduction into sulfide. The enrichments in Fe/Al and total sulfur observed at 164 and 182 meters depth in two muddy intervals below the carbonate are also likely pyrite (FeS2) enrichments, though they were not directly quantified here.

Atmospheric and sedimentary controls on anomalous sulfur

Barites isolated from Kazput carbonate show the ∆36S/∆33S slope of −0.9 (Fig. 3a) that typifies much of the Archaean sulfur isotope record. This slope, however, steepens to near −1.5 within the upper and lower portion of the carbonate (Fig. 2). Close links between low δ13C values and steeper ∆36S/∆33S slopes (−1.5) in Neoarchaean sedimentary rocks52 have been interpreted as evidence for changes in atmospheric chemistry catalysed by the biosphere53. In comparison to these Neoarchaean records, however, Kazput barite show relatively small ∆36S and ∆33S ranges. Furthermore, recent iron-speciation and nitrogen isotope evidence imply that suboxic-to-oxic water column conditions prevailed beneath an atmosphere containing appreciable oxygen31. The apparent availability of significant free O2 (>0.001% PAL), concurrent with mass independent sulfur isotope anomalies, strongly supports the latter being due to a memory effect carried by sulfate derived from oxidative weathering of S-MIF-bearing rocks15. It follows that the attendant ∆36S/∆33S variations in the barites may reflect control from oxidative weathering of pyrite in continental source rocks of various ages, whereas the S-MIF signal is simply tracking the integrated sulfur isotope composition of the rocks being weathered. As interpreted previously, the S-MIF systematics and their limited range in the Turee Creek Group may represent homogenisation during the weathering of older, more isotopically variable sulfur generated under earlier atmospheric states, together with dilution by addition of sulfate lacking S-MIF (∆33S ≈ 0‰)16.

Despite being deposited in relative proximity, within similar equatorial intracratonic basins7,12,30, W. Australian and S. African records display stark sulfur isotopic differences between 2.45 and 2.2 Ga. These differences may partly reflect spatial and temporal variations of SO42− concentrations. Geochemical constraints from the first basin-scale bedded evaporites at 2 Ga indicate a significant marine SO42− concentration of at least 10 mM54, however, between 2.25 and 2.1 Ga, the δ34S variability in extant CAS records imply a range of seawater SO42− concentrations of 5-20 mM55. Meanwhile, modern analog environments suggest late Archaean marine SO42− concentrations of <2.5 μM56. As a result of such sulfate concentrations that could span four orders of magnitude between 2.5 and 2.1 Ga, sulfur isotope variations would be very sensitive to local environmental controls. We suggest that such local control extends to the record of sulfur isotope anomalies. As compared to S. Africa, the W. Australian Turee Creek Group succession seems to require within-sediment closed system MSR to preserve its persistent S-MIF signals. Frequency distributions of δ34S data support this assertion, with W. Australian sulfur δ34S data displaying a broadly unimodal distribution, centered near 5‰ (Fig. 4a); while S. African data show a more bimodal δ34S distribution (Fig. 4b), reflecting the preferential incorporation of 32S into sulfide at the expense of sulfate. These different behaviors are also manifested in their respective ∆33S distributions. Despite similar ranges of ∆33S values, an important source of mass-dependent sulfur (∆33S ≈ 0‰, Fig. 4d) is indicated for S. Africa, while two sources of S-MIF-bearing sulfur (∆33S =+0.9‰ and +1.6‰, Fig. 4c) are observed from W. Australia. Closed system MSR is also suggested by the δ34S-∆33S systematics. Similar to previous observations from microbial carbonates57, the 34S-enrichment versus the ARA seen in Kazput pyrites and barites (Fig. 3b) could reflect the isolation of the sediment from the water column due to carbonate precipitation. Indeed, stromatolites and carbonate are prevalent throughout the Turee Creek Group, especially in the Kazput Formation. Finally, to help elucidate the possibility that the Turee Creek Basin may have been relatively more isolated from the global ocean as compared to contemporaneous S. African basins, the δ18O compositions of CAS from S. Africa may be useful but are yet to be measured. As suggested by the S-isotope evidence for open system MSR, it is likely that sulfate from S. Africa is relatively enriched in 18O as compared to the Kazput barite.

Histogram density plots of bulk sulfur isotope data of sulfides and sulfates from S. Africa and W. Australia of ca. 2.2–2.45 Ga age. The data are organised by δ34S (a, b) and ∆33S (c, d). The plots of S. African δ34S (b) and ∆33S (d) data (δ34Ssulfide n = 217, δ34Ssulfate n = 28, ∆33Ssulfide n = 164 and ∆33Ssulfate n = 26) are from6,12,13,69. W. Australian δ34S (a) and ∆33S (c) sulfide data (δ34Ssulfide and ∆33Ssulfide n = 75) are from16, while sulfate data (δ34Ssulfate and ∆33Ssulfate n = 24) are from this study. Source data are compiled in the Source Data file. Note that the ∆33S range truncates the maximum value observed from the S. African records (7.35‰). We refrain from comparing against time-equivalent N. American data due to its sulfur isotope records being possibly compromised by metamorphic overprinting37

Implications for constraining atmospheric oxygenation

Beyond its production in an essentially oxygen-free atmosphere, the preservation of S-MIF is susceptible to second-order biotic and abiotic controls. Consequently, several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the temporal structure of the S-MIF record (Fig. 1a). For example, the enhanced preservation of large magnitude ∆33S compositions in the lead up to 2.5 Ga have been explained by a shift in the locus of MSR from euxinic water columns to sediment porewaters due to oxygenation of shallow surface oceans58, or by the changing oxidation state of gas influxes59. Conversely, contraction of ∆33S signals, such as observed in pyrite between 2.5 and 2.3 Ga, could be caused by dilution of sulfur isotope anomalies with sulfide biologically produced from mass-dependent sulfur sources58. The ca. 2.5–2.3 Ga weak signals of S-MIF could reflect millions of years of weathering out and dilution of anomalous sulfur that had previously been stockpiled in more reduced, pre-GOE (i.e., older), sediments14,15, as is likely the case for the Turee Creek Group16. Another possibility is that oscillating atmospheric oxygen levels after 2.5 Ga7 permitted intervals of primary atmospheric S-MIF production and preservation as oxygen intermittently dipped below 0.001% PAL. In any case, it remains difficult to clearly recognize these various scenarios because the signals they leave behind in sediments can be ambiguous. Perhaps more detailed examination of linked δ13C and ∆36S/∆33S slope variations from ca. 2.5 to 2.3 Ga will reveal more about the possibly of oscillating levels of atmospheric gases in that interval. That oxidative weathering should be the main control on marine sulfate after atmospheric oxygenation seems intuitive, but as mentioned, even under the high atmospheric oxygen concentration of the modern Earth, surface weathering does not directly control marine sulfate S-isotope values in lieu of MSR. The dominance of positive ∆33S values in the Kazput barites implies the SO42− originated from the oxidative weathering of pre-GOE sedimentary rocks. Our results are at odds with the conclusion, based on contemporary weathering of old exposures, that the weathering of Archaean continents would yield sulfate with ∆33S summing to nearly 0‰17. Perhaps this discrepancy is because present-day rock exposures simply are not comparable in composition and weathering susceptibility to the exposed sedimentary rocks at Earth's surface in the Palaeoproterozoic. Furthermore, small positive ∆33S have indeed been measured in riverine sulfate from catchments in S. Africa and Ontario today60, which suggests that recycling of S-MIF signals at the Earth surface could occur at least locally. From the Archaean to the the earliest Palaeoproterozoic ca. 2.5–2.3 Ga, when sulfur was being delivered by incipient oxidative weathering and/or atmospheric inputs, the marine SO42− reservoir was smaller and its fraction buried as pyrite approached unity2. Under these conditions, it is possible that the S-isotope compositions of marine sulfate and sulfide records could approach those of S-MIF-bearing riverine SO42− sources. In turn, early Palaeoproterozoic sulfur records, especially from basins with an unknown degree of connection to the global ocean, can be expected to show substantial variability. As spatial and temporal coverage of Palaeoproterozoic sulfide and sulfate records increases, a clearer composite portrait should emerge that will allow for more clearly differentiated local versus global symptoms of atmospheric oxygenation being recognized in the sulfur cycle at different scales.

Our findings suggest that the oxygen isotope composition of sulfate may prove as insightful as multiple sulfur isotope data in evaluating the imprint of atmospheric oxygenation within the sedimentary record. The combined negative δ18O and positive ∆33S compositions of Kazput barite imply weathering, as opposed to atmospheric, control on sulfur input fluxes by ~2.31 Ga in the Turee Creek Basin. It follows that the onset of atmospheric oxygenation and its nascent imprint on the sulfur record must be older. It has been suggested that SO42− flux to the oceans increased in advance of the GOE due to oxygen production and its consumption by sulfide weathering on land61,62 (Fig. 1c). The conspicuous absence of negative ∆33S anomalies from rocks younger than 2.42 Ga (Fig. 1a) may mark the turning point when weathering derived SO42− fluxes, with predominantly positive ∆33S anomalies, first dominated the surficial sulfur cycle. By using oxygen isotope compositions to identify sulfide-derived sulfates of continental weathering origin from the rock record, it may be possible to directly constrain the timing of early weathering fluxes of SO42− and their relative significance for the late Archaean surficial sulfur and oxygen cycles.

Methods

CAS extraction

Carbonate-associated sulfate extractions were completed at the Laboratoire Géosciences Océan at IUEM in Plouzané, France. Drill core samples were first manually crushed in a tungsten-carbide piston chamber before powdering in an agate ring and puck mill. Following the CAS extraction sequence tested by Wotte et al.63, soluble sulfate phases were removed from powdered carbonate samples via triplicate 10% NaCl leaches. The carbonate component was then dissolved by slow addition of 12 M HCl until no reaction was observed, thus liberating CAS into solution. The CAS was then precipitated as BaSO4 upon addition of a supersaturated BaCl2 solution. The resulting trivial CAS yields could be readily compromised by laboratory-induced pyrite oxidation from Kazput samples (~0.32 weight % pyrite, Supplementary Table 2). Therefore, we developed a modified CAS extraction protocol, using the reducing agent hydroxylamine hydrochloride to inhibit pyrite oxidation during CAS extraction. Unfortunately, the hydroxylamine hydrochloride itself was found to contain sufficiently concentrated trace sulfate to contaminate the CAS sample target. The result of CAS extraction with hydroxylamine hydrochloride on Kazput carbonate sample gave a final yield of <2 ppm whole-rock CAS, all of which could be attributed to contamination from the hydroxylamine hydrochloride. Thus, it was concluded that CAS in these samples is too low for precise bulk S- and O-isotope measurements, and CAS extractions on these samples was not pursued further.

Barite extraction

Our barite extraction technique utilises a chelating agent that at once enables dissolution of barite while inhibiting the oxidation of pyrite. Again, the barite extractions were completed at the Laboratoire Géosciences Océan at IUEM in Plouzané, France. As a test for pyrite oxidation in our extraction technique, finely ground pyrite was stirred in the chelating solution for a week followed by attempted recovery of pyrite-derived SO42− from the filtered solution, with no resulting sulfate yield, likely because the chelation of iron and other metal cations also served to prevent pyrite oxidation. In addition, we intentionally oxidized pyrite in the same laboratory-distilled water that is used in the barite extracting solution followed by measurement of the oxygen isotope composition of the produced sulfate, which was isotopically distinct from that of the measured samples (Supplementary Fig. 7).

Barite in TCDP3 was only observed by scanning electron microscopy, where barites <10 μm were observed in both sample residues (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4) and in thin sections. Barite was not observed during conventional optical petrographic observations of thin sections. Barite extractions were performed on ~100 g of powdered drill core rock sample using a modified barite purification technique (the DDARP method) from Bao 200664 that was originally developed to purify sulfate samples for triple oxygen isotope measurements. Sample powders were decarbonated in HCl-acidified solution, rinsed in distilled water, and then treated for 3 days with constant stirring in a 0.05 M Diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) and 1 M NaOH solution to dissolve barium sulfate. The supernatant was then separated from the sample residue by vacuum filtration. After acidification (pH < 2) with HCl, the barite-housed sulfate was precipitated out of the supernatant as BaSO4 via addition of supersaturated BaCl2 solution. Co-precipitation of silicates dissolved in the basic DTPA solution renders the precipitated BaSO4 impure, requiring an additional purification step. Here, residual DTPA must first be removed by triplicate washing with distilled water, centrifugation, and decanting of the supernatant. After heated overnight at 70 °C in a 2 M NaOH solution, the sample was again centrifuged and the supernatant decanted. The sample was once again redissolved in 0.05 M DTPA and 1 M NaOH solution by agitating overnight then re-precipitated by acidification with HCl (to pH < 2) and addition of BaCl2 solution. The BaSO4 precipitate is finally washed in triplicate and dried at 70 °C overnight, then ready for isotope analysis.

Oxygen isotope (δ18O) measurements

Purified barite samples were measured in duplicate on an Elementar vario PYRO cube elemental analyzer in-line with an Isoprime 100 mass spectrometer in continuous flow mode at the University of Burgundy in Dijon, France. Oxygen isotope data are expressed in delta notation, δ ≡ Rsample/Rstandard − 1, where R is the mole ratio of 18O/16O and reported in units per mille (‰, i.e.×1000). The δ18O data are reported with respect to the international standard Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (VSMOW). Analytical errors are ±0.4‰ (2σ) based on replicate analyses (n = 21) of the international barite standard NBS-127 (Supplementary Table 4), which was used for data correction via standard-sample-standard bracketing.

Quadruple sulfur isotope (δ34S, ∆33S and ∆36S) measurements

Purified barite samples required additional wet chemistry for quadruple sulfur isotope analysis, all done at the Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris in Paris, France. Approximately 3 mg of each barite sample was converted to Ag2S by heating in an anoxic distillation apparatus in a sub-boiling solution of HCl, HI, and H3PO2 after Thode, Monster and Dunford65 and Pepkowitz and Shirley66. Barite was thus converted to H2S that was then flushed by N2 gas to an awaiting trap of silver nitrate solution where the H2S was precipitated as Ag2S. The sample Ag2S precipitate was washed in triplicate in distilled water, oven-dried overnight, then ready for sulfur isotope analysis.

Quadruple sulfur isotope analyses were made by first heating ~3 mg sample Ag2S under an excess of F2 gas (~300 torr) at 350 °C in nickel bombs overnight. The produced SF6 gas was then purified via cryogenic trapping and separation by gas chromatograph before introduction to the mass spectrometer, a Thermo Finnigan MAT 253 running in dual inlet mode, for determination of quadruple sulfur isotope composition. Delta notation is used to report 34S, with δ ≡ Rsample/Rstandard − 1, where R is the mole ratio of 34S/32S and reported in units per mille (‰). The minor isotopes 33S and 36S are reported in capital delta notation, where ∆33S = δ33S – ((δ34S/1000 + 1)0.515 – 1) × 1000‰ and ∆36S = δ36S – ((δ34S/1000 + 1)1.89 – 1) × 1000‰. The δ34S, ∆33S and ∆36S data are reported with respect to the Vienna Canyon Diablo Troilite (VCDT) international standard, with analytical errors of ±0.1‰, ±0.01‰ and ±0.2‰ (2σ), respectively, as based on the long-term reproducibility of analyses of the international standard IAEA S-1 (Supplementary Table 5).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Change history

30 September 2020

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

References

Burke, A. et al. Sulfur isotopes in rivers: insights into global weathering budgets, pyrite oxidation, and the modern sulfur cycle. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 496, 168–177 (2018).

Canfield, D. E. & Farquhar, J. Animal evolution, bioturbation, and the sulfate concentration of the oceans. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 8123–8127 (2009).

Johnston, D. T., Farquhar, J. & Canfield, D. E. Sulfur isotope insights into microbial sulfate reduction: when microbes meet models. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 71, 3929–3947 (2007).

Paytan, A., Kastner, M., Campbell, D. & Thiemens, M. H. Sulfur isotopic composition of Cenozoic seawater sulfate. Science 282, 1459–1462 (1998).

Farquhar, J., Bao, H. & Thiemens, M. Atmospheric influence of Earth's earliest sulfur cycle. Science 289, 756–758 (2000).

Guo, Q. et al. Reconstructing Earth's surface oxidation across the Archean-Proterozoic transition. Geology 37, 399–402 (2009).

Gumsley, A. P. et al. Timing and tempo of the great oxidation event. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 1811–1816 (2017).

Paris, G., Adkins, J. F., Sessions, A. L., Webb, S. M. & Fischer, W. W. Neoarchean carbonate-associated sulfate records positive ∆33S anomalies. Science 346, 739–741 (2014).

Claire, M. W. et al. Modeling the signature of sulfur mass-independent fractionation produced in the Archean atmosphere. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 141, 365–380 (2014).

Pavlov, A. & Kasting, J. Mass-independent fractionation of sulfur isotopes in Archean sediments: strong evidence for an anoxic Archean atmosphere. Astrobiology 2, 27–41 (2002).

Halevy, I. Production, preservation, and biological processing of mass-independent sulfur isotope fractionation in the Archean surface environment. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 110, 17644–17649 (2013).

Bekker, A. et al. Dating the rise of atmospheric oxygen. Nature 427, 117–120 (2004).

Luo, G. et al. Rapid oxygenation of Earth’s atmosphere 2.33 billion years ago. Sci. Adv. 2, e1600134 https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/2/5/e1600134 (2016).

Farquhar, J. & Wing, B. A. Multiple sulfur isotopes and the evolution of the atmosphere. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 213, 1–13 (2003).

Reinhard, C. T., Planavsky, N. J. & Lyons, T. W. Long-term sedimentary recycling of rare sulfur isotope anomalies. Nature 497, 100–104 (2013).

Philippot, P. et al. Globally asynchronous sulfur isotope signals require re-definition of the Great Oxidation Event. Nat. Commun. 9, 2245 (2018).

Torres, M. A., Paris, G., Adkins, J. F. & Fischer, W. W. Riverine evidence for isotopic mass balance in the Earth’s early sulfur cycle. Nat. Geosci. 11, 661–664 (2018).

Peng, Y. et al. Widespread contamination of carbonate-associated sulfate by present-day secondary atmospheric sulfate: evidence from triple oxygen isotopes. Geology 42, 815–818 (2014).

Rennie, V. C. F. & Turchyn, A. V. The preservation of δ34SSO4 and δ18OSO4 in carbonate-associated sulfate during marine diagenesis: a 25 Myr test case using marine sediments. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 395, 13–23 (2014).

Fichtner, V. et al. Diagenesis of carbonate associated sulfate. Chem. Geol. 463, 61–75 (2017).

Griffith, E. M. & Paytan, A. Barite in the ocean—occurrence, geochemistry and palaeoceanographic applications. Sedimentology 59, 1817–1835 (2012).

Crockford, P. W. et al. Claypool continued: extending the isotopic record of sedimentary sulfate. Chem. Geol. 513, 200–225 (2019).

Luz, B. & Barkan, E. Variations of 17O/16O and 18O/16O in meteoric waters. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 74, 6276–6286 (2010).

Bao, H. Sulfate: a time capsule for Earth's O2, O3, and H2O. Chem. Geol. 395, 108–118 (2015).

Kasting, J. F. et al. Paleoclimates, ocean depth, and the oxygen isotopic composition of seawater. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 252, 82–93 (2006).

Antler, G., Turchyn, A. V., Ono, S., Sivan, O. & Bosak, T. Combined 34S, 33S and 18O isotope fractionations record different intracellular steps of microbial sulfate reduction. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 203, 364–380 (2017).

Trendall, A., Compston, W., Nelson, D., De Laeter, J. & Bennett, V. SHRIMP zircon ages constraining the depositional chronology of the Hamersley Group, Western Australia. Aust. J. Earth Sci. 51, 621–644 (2004).

Caquineau, T., Paquette, J.-L. & Philippot, P. U-Pb detrital zircon geochronology of the Turee Creek Group, Hamersley Basin, Western Australia: timing and correlation of the Paleoproterozoic glaciations. Precambrian Res. 307, 34–50(2018).

Müller, S. G., Krapez, B., Barley, M. E. & Fletcher, I. R. Giant iron-ore deposits of the Hamersley province related to the breakup of Paleoproterozoic Australia: New insights from in situ SHRIMP dating of baddeleyite from mafic intrusions. Geology 33, 577–5580 (2005).

Van Kranendonk, M. J., Mazumder, R., Yamaguchi, K. E., Yamada, K. & Ikehara, M. Sedimentology of the Paleoproterozoic Kungarra Formation, Turee Creek Group, Western Australia: a conformable record of the transition from early to modern Earth. Precambrian Res. 256, (314–343 (2015).

Cheng, C. et al. Nitrogen isotope evidence for stepwise oxygenation of the ocean during the Great Oxidation Event. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta. 261, 224–247 (2019).

Martindale, R. C. et al. Sedimentology, chemostratigraphy, and stromatolites of lower Paleoproterozoic carbonates, Turee Creek Group, Western Australia. Precambrian Res. 266, 194–211 (2015).

Barlow, E., Van Kranendonk, M., Yamaguchi, K., Ikehara, M. & Lepland, A. Lithostratigraphic analysis of a new stromatolite–thrombolite reef from across the rise of atmospheric oxygen in the Paleoproterozoic Turee Creek Group, Western Australia. Geobiology 14, 317–343 (2016).

Gomes, M. L. & Johnston, D. T. Oxygen and sulfur isotopes in sulfate in modern euxinic systems with implications for evaluating the extent of euxinia in ancient oceans. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 205, 331–359 (2017).

Balci, N., Shanks, W. C., Mayer, B. & Mandernack, K. W. Oxygen and sulfur isotope systematics of sulfate produced by bacterial and abiotic oxidation of pyrite. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 71, 3796–3811 (2007).

Hanor, J. S. Barite–celestine geochemistry and environments of formation. Rev. Mineral. Geochem. 40, 193–275 (2000).

Cui, H. et al. Searching for the Great Oxidation Event in North America: a reappraisal of the huronian supergroup by sims sulfur four-isotope analysis. Astrobiology 18, 519–538 (2018).

Smith, R. E., Perdrix, J. & Parks, T. Burial metamorphism in the Hamersley basin, Western Australia. J. Petrol. 23, 75–102 (1982).

Williford, K. H., Van Kranendonk, M. J., Ushikubo, T., Kozdon, R. & Valley, J. W. Constraining atmospheric oxygen and seawater sulfate concentrations during Paleoproterozoic glaciation: in situ sulfur three-isotope microanalysis of pyrite from the Turee Creek Group, Western Australia. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 75, 5686–5705 (2011).

Reinhard, C. T., Lalonde, S. V. & Lyons, T. W. Oxidative sulfide dissolution on the early earth. Chem. Geol. 362, 44–55 (2013).

Lefticariu, L., Pratt, L. A., LaVerne, J. A. & Schimmelmann, A. Anoxic pyrite oxidation by water radiolysis products—a potential source of biosustaining energy. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 292, 57–67 (2010).

Ryb, U. & Eiler, J. M. Oxygen isotope composition of the Phanerozoic ocean and a possible solution to the dolomite problem. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 6602–6607 (2018).

Van Everdingen, R. O. & Krouse, H. R. Interpretation of isotopic compositions of dissolved sulfates in acid mine drainage: Information Circular 9183. (United States Bureau of Mines, 1988).

Schopf, J. W. et al. Sulfur-cycling fossil bacteria from the 1.8-Ga Duck Creek Formation provide promising evidence of evolution's null hypothesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 112, 2087–2092 (2015).

Fry, B., Gest, H. & Hayes, J. S. 34S/32S fractionation in sulfur cycles catalyzed by anaerobic bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 54, 250–256 (1988).

Brunner, B. et al. The reversibility of dissimilatory sulphate reduction and the cell-internal multi-step reduction of sulphite to sulphide: insights from the oxygen isotope composition of sulphate. Isot. Environ. Health Stud. 48, 33–54 (2012).

Peng, Y., Bao, H., Zhou, C., Yuan, X. & Luo, T. Oxygen isotope composition of meltwater from a Neoproterozoic glaciation in South China. Geology 41, 367–370 (2013).

Galili, N. et al. The geologic history of seawater oxygen isotopes from marine iron oxides. Science 365, 469–473 (2019).

Calmels, D., Gaillardet, J., Brenot, A. & France-Lanord, C. Sustained sulfide oxidation by physical erosion processes in the Mackenzie River basin: climatic perspectives. Geology 35, 1003–1006 (2007).

Killingsworth, B. A., Bao, H. & Kohl, I. E. Assessing pyrite-derived sulfate in the Mississippi River with four years of sulfur and triple-oxygen isotope data. Environ. Sci. Technol. 52, 6126–6136 (2018).

Magnall, J. et al. Open system sulphate reduction in a diagenetic environment–Isotopic analysis of barite (δ34S and δ18O) and pyrite (δ34S) from the Tom and Jason Late Devonian Zn–Pb–Ba deposits, Selwyn Basin, Canada. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 180, 146–163 (2016).

Thomazo, C., Nisbet, E. G., Grassineau, N. V., Peters, M. & Strauss, H. Multiple sulfur and carbon isotope composition of sediments from the Belingwe Greenstone Belt (Zimbabwe): a biogenic methane regulation on mass independent fractionation of sulfur during the Neoarchean? Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 121, 120–138 (2013).

Izon, G. et al. Biological regulation of atmospheric chemistry en route to planetary oxygenation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci USA 114, E2571–E2579 (2017).

Blättler, C. L. et al. Two-billion-year-old evaporites capture Earth’s great oxidation. Science. 360, 320–323 (2018).

Planavsky, N. J., Bekker, A., Hofmann, A., Owens, J. D. & Lyons, T. W. Sulfur record of rising and falling marine oxygen and sulfate levels during the Lomagundi event. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 18300–18305 (2012).

Crowe, S. A. et al. Sulfate was a trace constituent of Archean seawater. Science 346, 735–739 (2014).

Ono, S., Kaufman, A. J., Farquhar, J., Sumner, D. Y. & Beukes, N. J. Lithofacies control on multiple-sulfur isotope records and Neoarchean sulfur cycles. Precambrian Res. 169, 58–67 (2009).

Fakhraee, M., Crowe, S. A. & Katsev, S. Sedimentary sulfur isotopes and Neoarchean ocean oxygenation. Sci. Adv. 4, e1701835 https://advances.sciencemag.org/content/4/1/e1701835 (2018).

Halevy, I., Johnston, D. T. & Schrag, D. P. Explaining the structure of the Archean mass-independent sulfur isotope record. Science 329, 204–207 (2010).

Asael, D., Planavsky, N., Bellefroid, E., Hofmann, A. & Reinhard, C. in Goldschmidt (Paris, 2017).

Stüeken, E. E., Catling, D. C. & Buick, R. Contributions to late Archaean sulfur cycling by life on land. Nat. Geosci. 5, 722–725 (2012).

Lalonde, S. V. & Konhauser, K. O. Benthic perspective on Earth's oldest evidence for oxygenic photosynthesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 995–1000 (2015).

Wotte, T., Shields-Zhou, G. A. & Strauss, H. Carbonate-associated sulfate: Experimental comparisons of common extraction methods and recommendations toward a standard analytical protocol. Chem. Geol. 326-327, 132–144 (2012).

Bao, H. Purifying barite for oxygen isotope measurement by dissolution and reprecipitation in a chelating solution. Anal. Chem. 78, 304–309 (2006).

Thode, H., Monster, J. & Dunford, H. Sulphur isotope geochemistry. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 25, 159–174 (1961).

Pepkowitz, L. & Shirley, E. Microdetection of sulfur. Anal. Chem. 23, 1709–1710 (1951).

Lyons, T. W., Reinhard, C. T. & Planavsky, N. J. The rise of oxygen in Earth's early ocean and atmosphere. Nature 506, 307–315 (2014).

Ono, S. Photochemistry of sulfur dioxide and the origin of mass-independent isotope fractionation in earth's atmosphere. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 45, 301–329 (2017).

Cameron, E. M. Sulphate and sulphate reduction in early Precambrian oceans. Nature 296, 145–148 (1982).

Acknowledgements

We thank Nelly Assayag, Amaury Bouyon, Théophile Cocquerez, and Céline Liorzou for assistance in the lab, James Farquhar for discussions and Tim Lyons, Guillaume Paris and Gareth Izon for their highly constructive reviews that improved this manuscript. This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 708117. This work was also supported by grants from the UnivEarthS Labex Programme at Université Sorbonne Paris Cité (ANR-10-LABX-0023 and ANR-11-IDEX-0005-02), as well as a Region of Brittany Strategy of Attractivity Grant (SAD Project S-GEOBIO, No 0461/14007339/00001041 and 0461/14007349/00001041). P.P. acknowledges support from the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP, grant 2015/16235-2).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was conceived by B.K., S.L., P.S., P.P. and P.C. Samples were provided by P.P. with the assistance of Turee Creek Drilling Project collaborators. B.K. prepared samples with the assistance of S.L. and P.S. B.K. analyzed samples with the assistance of P.C. and C.T. All authors interpreted data. B.K. wrote the paper with contributions from all co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Gareth Izon, Timothy Lyons and Guillaume Paris for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Killingsworth, B.A., Sansjofre, P., Philippot, P. et al. Constraining the rise of oxygen with oxygen isotopes. Nat Commun 10, 4924 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12883-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-12883-2

This article is cited by

-

Reconciling discrepant minor sulfur isotope records of the Great Oxidation Event

Nature Communications (2023)

-

A 200-million-year delay in permanent atmospheric oxygenation

Nature (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.