Abstract

Ultrathin transition metal carbides with high capacity, high surface area, and high conductivity are a promising family of materials for applications from energy storage to catalysis. However, large-scale, cost-effective, and precursor-free methods to prepare ultrathin carbides are lacking. Here, we demonstrate a direct pattern method to manufacture ultrathin carbides (MoCx, WCx, and CoCx) on versatile substrates using a CO2 laser. The laser-sculptured polycrystalline carbides (macroporous, ~10–20 nm wall thickness, ~10 nm crystallinity) show high energy storage capability, hierarchical porous structure, and higher thermal resilience than MXenes and other laser-ablated carbon materials. A flexible supercapacitor made of MoCx demonstrates a wide temperature range (−50 to 300 °C). Furthermore, the sculptured microstructures endow the carbide network with enhanced visible light absorption, providing high solar energy harvesting efficiency (~72 %) for steam generation. The laser-based, scalable, resilient, and low-cost manufacturing process presents an approach for construction of carbides and their subsequent applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Transition metal carbides (TMCs) have unique characteristics such as low resistivity (metallic), high melting temperature, and high electrochemical activities for energy storage and catalysis1. Dimensional reduction of bulk TMCs to 0-, 1-, or 2-dimensional nanostructures (thickness vs lateral size < 1 %)2,3 has attracted interest as a means to provide further control over a range of properties as well as to introduce new functionality4,5,6. TMCs in particular have gained recent attention due to their intriguing physical, electrical, and catalytical properties. In general, the state-of-the-art fabrication process for ultrathin 2D-TMCs (MXenes)7,8,9,10 involves high temperatures (up to 1600 °C)11 to generate the MAX phase (Mn+1AXn, where M is a transition metal, A is a group 12–16 element, and X is C or N) precursor and then a hydrofluoric (HF) acid etching process to remove the A layer to form Mn+1XnTx (T: OH, OOH and other surface terminations)9,12,13,14. Fluoride-free methods for preparing ultrathin TMCs have been reported, notably chemical vapor deposition (CVD) on metal foils or graphene but the yield is extremely low3,15,16. Therefore, development of a robust, mild temperature, versatile fabrication, and precursor independent method for ultrathin TMCs is required to enlarge the family of ultrathin-TMCs, expand the understanding of their properties, and enable cost-effective large-scale synthesis. Meanwhile, the etched MXenes sheets are terminated by rich surface functional groups such as –OH and –COOH, which could change the properties of intrinsic carbide. For example, Ti3C2Tx decay at 200 °C due to the collapse of surface groups17 while the Ti3C2 shall survive up to 1000 °C. Synthesis of “purer” TMC beyond MXenes will empower researchers with wide opportunities to study their intrinsic physics and chemistry. Beyond the synthesis of the materials, their facile integration into devices represents another key challenge in realizing the potential of TMCs for applications. Devices made from chemically synthesized TMCs require further lithography steps; instead, a direct patterning method would enable roll-to-roll manufacturing of host of potential applications from energy storage devices18 to wireless communication19.

Herein, we demonstrate a versatile process to fabricate transition metal carbides in the form of ultrathin flakes with few-nanometer thickness. The approach utilizes laser ablation of a lamellar hydrogel/metal-ion matrix (metallo-hydrogel). Gelatin, commonly found in jelly desserts, can undergo a self-assembly process to form membranes in a layer-by-layer ordering20,21,22. By selecting carbide-forming metal ions (Mo5+, W6+, and Co2+), a nanostructured hydrogel can be prepared that is ablated for subsequent conversion into TMCs that retain their supramolecular layer-by-layer structure23,24. When a hydrogel with embedded transition metal ions is heated, self-accumulation of polymeric phases of metal carbide degradation products occurs at the hydrogel air/liquid interface in a process described by the Buoyancy–Marangoni effect (Fig. 1a–d)25,26,27. The self-assembly and ordering of gelatin can therefore macroscopically arrange precursors into structures that can be collapsed into dimensionally conserved nanostructures28,29. When ablated by a CO2 laser (Fig. 1e), metallo-gel absorbs IR energy which generates high temperatures (over 2000K, supporting information) within a rapid uptake time (sub millisecond timescale)30. Residual solvent and carbon source from the gel “explosively” vaporizes and reacts with metal ions to form carbide structures (MoCx, WCx, and CoCx) with macroporous (50–1000 nm pore size31,32). The metallo-hydrogel can be easily spin coated onto a variety of substrates including glass (Supplementary Fig. 1). A common commercial cutter (VLS 2.30, Universal Laser) can directly pattern features (Fig. 1f) and integrate electrodes for microdevices with resolution of 25 microns. The laser-patterned carbide, using MoCx as an example, performs as an energy storage interdigit supercapacitor electrode having a wide operational temperature range (−50 °C to 300 °C in electrolyte). Furthermore, the single laser step not only produce ultrathin-TMC, but also pop up the ultrathin sheets into 3D microstructure with interconnected surface. As-sculptured structure provide more tunability in optical, electrical, and mechanical properties. For example, a membrane made of surface curved MoCx can localize light with the to enhance solar energy harvesting (72% energy efficiency, evaporation total enthalpy over incident solar illumination energy). The exceptional thermal resilience of TMCs could enable a range of other applications such as carbide-based supercapacitors or solar-steam generation membranes operating in harsh environments.

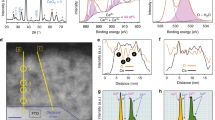

Schematic of laser-sculptured ultrathin transition metal carbides. a Process for producing laser-induced transition metal carbides. Helical polymer gelatin mediated transition metal ions (metallo-hydrogel) are used to form a layer-by-layer structure. b, c Grazing incident wide angle X-ray scattering (GIWAX) characterizations of metallo-gels. b GIWAX of W-gelatin made dissolved in NMP (N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone)32. c Integration of GIWAX scattering data of Mo-gel and W-gelatin-NMP. d GIWAX of Mo-gelatin template as an example to show that gelatin constrains the metal ions laterally between the layers32. The Mo1, W1, and W2 peaks correspond to peaks in the GIWAX scattering in b and d and show how the ion type and solvent in the template greatly affect the assembled layer distributions. e IR laser ablation generates highly porous structures with interconnected curved surfaces, for which the “wall” thickness reaches down to the nanometer scale. f Using the molybdenum ion as an example, carbide features of “MIT” and “Cal” are engraved on a yellowish transparent thin film (~8 μm in thickness) spin-coated onto a glass substrate with a computer aided design software. g Confocal image of 3D tomography or a selected area of laser-sculptured carbide. h TEM image of laser synthesized MoCx. i High resolution TEM images of MoCx showing the sizes of nanocrystals are around 10 nm. j Selected area diffraction of MoCx. The diffraction ring indicates a polycrystalline structure within the carbide layer

Results

Materials characterizations and properties

The local high-temperature generated rapidly by the IR laser pulse33 (Table S1), enables an instantaneously high carbon uptake and induces higher energy phases (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Fig. 3)34. Within 30 μs the accumulated temperature can reach up to 2000 K in the Mo-gel thin film (Supplementary Fig. 3a–c) with a projected power of 4 W, using Mo-gel (2 molal, 60% wt) as an example. The rapid initial uptake leads to the formation of the carbon-deficient, metastable phase α-MoCx instead of the thermodynamically stable Mo-C (α/β-Mo2C) phases (Supplementary Fig. 2). A simplified heat transfer model was employed to estimate the temperature profile (Supporting Information), with approximate timescale within the range of µs to ms35. The laser energy input produces this high energy α-MoCx (0 < x < 1) phase of MoCx (Supplementary Fig. 2), which has a threshold temperature of 1928 K in the phase diagram The product of α-MoCx/C has a much higher Gibbs free energy than the common α-Mo2C and β-Mo2C36,37,38 and the 2D-Mo2C achieved by CVD3,15,16. Chemically exfoliated Mo2CTx2,39 corresponds to β-Mo2C, which is a lower energy phase compared to α-MoCx. Confocal optical mapping of the laser-induced carbide (using MoCx as an example), shows three-dimensional curved porous structure (Fig. 1g), and the slices of different confuse plane shows different cross section in the 3D tomography (Supplementary Fig. 4). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images show that the broken-down sheets of the porous structure have a thickness of 10–20 nm and are comprised of randomly orientated nanocrystals (Fig. 1h–j, Supplementary Fig. 4d–e). In comparison, for the cases of Mo-PEO and Mo-PVP, the temperature is much lower due to their lower IR absorption coefficients18, and the laser carbonized products are not recognized as any carbide phase (Supplementary Fig. 3d, e). Two other carbide phases β-W2C/W and Co2C/Co (Table 1, Supplementary Fig. 5), were not exfoliated from the corresponding MAX phases40.

Further technical details regarding the laser power, spot size, temperature profile and product are discussed in supporting information, Supplementary Fig. 6. A 2 W laser with a scan speed of 200 mm s−1 results in the smallest amount of amorphous carbon on Mo-gel (2 m, 60 wt%), and decent conductivity of ~3.2 S cm−1 for an 8-μm-thick spin-coated Mo-gel thin film (Fig. 1d), and is used as the standard protocol to pattern carbide devices in the rest of this paper. Electrical conductivities of laser-ablated carbides by different laser parameters are shown in Supplementary Fig. 7, and the optimized conductivities can reach ~300 S cm−1. Such conductivity, although not compatible with metal, is at a range of graphite (perpendicular to basal plane), amorphous carbon, carbon nanotube forest, and highly doped semiconductor41. The carbides hold BET surface area from ~10–30 m2g−1 (Supplementary Fig. 8). The electrically conductive porous materials can perform as electrodes for many electrochemistry applications such supercapacitor and battery42. A few carbide materials (Mo2C, WC, and etc) show remarkable electrocatalysis activity such as hydrogen evolution reactions32. The laser direct printed carbide electrodes are promising to be implemented in Noble-metal free electrocatalytic nanodevices. As shown in Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 9, the concentration of gelatin is essential for production of the carbide: above 10% all the products are in the form of carbide and carbon while below that concentration the product forms MoO2 and lower energy Mo2C. As revealed in Supplementary Fig. 10, the Mo-gelatin composite leads to the highest IR absorption at the typical wavelength of 10.6 μm compared to gelatin containing the same concentration of other metal ions43,44. W6+ and Co2+ gelatin induced carbides with metal phases, and both were metal/carbide composites represented by MCx (M = W, Co, Supplementary Fig. 5). The Ti4+ and Zr4+ in the gelatin hydrogel are converted to composite materials of carbides and oxides while Ni2+ and Fe3+ are converted to metal oxides with small portions of carbide. Zn2+ does not produce any crystalline phase (Supplementary Fig. 11).

Two critical parameters determine which mechanism and product are observed when forming laser-induced ultrathin TMC. The first key parameter is the “effectiveness” of energy absorbed by the metal-gelatin template, which is determined by the absorption of the ion, polymer and metal-ligand interactions. An additional critical factor is the activation energy of carbonization. Using Mo5+ and Ti4+ as two examples, Mo-gelatin can be effectively converted to MoCx at temperatures above 2000 K, while the ineffective energy conversion in the Ti-gelatin solution only activates the oxidation process to a more stable TiO4 phase. Even with the same component of metal gel and similar input laser power, a UV laser-induced metal and metal oxide phases instead of carbide phases. One possible reason is the lower temperature generated by lower absorption of UV power in metallo-hydrogel (Supplementary Fig. 12).

Further characterization of laser-induced MoCx is shown in Supplementary Fig. 13–14. We scratched off the as synthesized carbide and used high power ultrasonic processing to disperse flakes in ethanol (~20 μm in lateral size), which are then drop-cast onto silicon oxide. Atomic force microscopy (AFM) showed a thicknesses of carbide flakes between 10–20 nm, mostly <15 nm (Supplementary Figure 14).

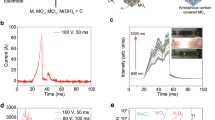

Flexible energy storage devices with wide operating temperature range

The nanocrystalline porous ultrathin flakes provide exceptionally high surface area and exposed edges, which result in a high specific capacitance up to 55 F g−1 in 1 M LiCl and long-term stability of 10,000 cycles (Supplementary Fig. 15). Flexible, high performance MoCx supercapacitor is patterned onto commercial Polyimide (PI) substrate. As shown in Fig. 2a, the Mo-gel is spin coated onto the PI tape, onto which interdigitated electrodes are then patterned. Unconverted Mo-gel is washed out, and highly concentrated PVA/LiTFSI electrolyte (20 molal) is coated. Supercapacitor device performance at different scanning rate is shown in Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 16. The MoCx supercapacitor shows over 90% maintenance of specific capacitance after 10,000 cycles (Fig. 2b). Lasing the commercial PI tape could induce porous graphene33, which will benefit the binding between laser-sculptured-carbide (LSC) and the flexible substrate both mechanically and electrically. Although LIG electrodes have also been used in supercapacitor (Fig. 2c), their temperature resilience is not compatible as laser scribed carbide45. As shown in in Fig. 2c, LIG electrodes in electrolyte turned to black color and damage in elevated temperature, while the LSC electrodes remains well functioning up to 300 °C. TGA of ultrathin-MoCx exhibits high-temperature stability up to 450 °C in air (Fig. 2c), which outperforms the previously reported MXene thermal stability temperature of ~200 °C in air17.

Flexible supercapacitor made of MoCx with a wide operating temperature range. a Processing schematic of fabricating the flexible MoCx supercapacitor. b Long-term retention of MoCx supercapacitor. Inset: cyclic voltammetry (CV) at different scanning rate. c Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) of MoCx. Inset, optical images of Carbide and LIG electrodes heated up to 300 °C. The molybdenum carbide electrodes could withstand temperatures reaching 300 °C while the laser-ablated graphene on PI in the below image decomposed to a black color. d TGA of Li-rich PVA electrolyte. e Specific capacitance recovers during the temperature cycle, and high-temperature performance of the MoCx electrodes. Inset: specific capacitance recovery in the temperature cycle. f CV results of carbide in LiTFSI/PVA/H2O electrolyte over the temperature cycle. g–h Low temperature performance of the MoCx electrodes

As shown in Fig. 2d, the electrolyte employed is a high concentration of 20 m LiTFSI/PVA with thermal stability up to 300 °C. Based on the freezing point depression46, which is positively correlated to the ion concentration, freezing point would possibly decrease to −74 °C as estimated in Supporting Information. The LSC film achieved low electrical resistivity around 50 Ω sq−1 and the resulting micro supercapacitor prototype showed good specific capacitance (2mF cm−2) at 100 mV s−1 (Fig. 2e). This flexible supercapacitor showed stable operation under charge-discharge cycling over a wide range of temperatures from −50 °C up to 300 °C (Fig. 2e–f). The cyclic voltammetry (CV) measurements at 25 °C before and after the harsh environment tests at 300 °C clearly show no decrease in performance for the MoCx-based supercapacitors (Fig. 2e). At low temperatures down to −50 °C, the MoCx-supercapacitor maintains functionality, with no perceptible irreversible damage to the electrodes according to the recovery of the CV curves after defrosting (Fig. 2f–h). Below −30 °C a sharp decay in capacitance is observed due to the low ion mobility in the freezing electrolyte. Further modifications such as adding anti-freeze agents or changing the solvent could stabilize the electrolyte at such low temperatures.

Solar-energy harvesting membrane made of carbide

In contrast to chemically exfoliated MXenes and CVD synthesized ultrathin carbides, laser-sculptured carbide possesses a built-in interconnected curved surface, which could enable the tailored design of 3D morphologies consisting of interconnected ultrathin materials. One way to take advantage of such structures is in light capture; for example, the highly porous and curved carbide “walls” can efficiently harvest solar energy and transfer it to water for the generation of steam. Laser-sculptured carbide is sonicated in a water/ethanol mixture to detach from a glass substrate. Vacuum filtration yields a flexible membrane on versatile substrate support including Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), Polyvinylidene (PVDF), and Polyethersulfone (PES) (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 17). The carbide membrane has strong absorption of a wide range solar spectrum, which induce local heating-driven evaporation at the water-air interface47. The solar-driven energy conversion at the interface reduce the energy input for bulk evaporation, which improve the steam productivity as shown in Fig. 3b–c48.

Laser-sculptured carbide for solar-steam generation membrane. a Fabrication schematic of carbide membrane. Laser-induced carbide is dispersed in DI water, which is condensed to a flexible membrane by vacuum filtration. b Solar-steam generation using carbide membrane to harvest solar-thermal energy. c Evaporation rate and energy efficiency of carbide membrane under different incident solar power. d Temperature file of MoC1-x under extreme solar irradiation (11 sun, inset). XPS of MoC1-x Mo_3d orbital before and after 11 sun exposure for 1 h. e Simulated refractive index, dielectric constant, and absorption coefficient of MoC1-x by density functional theory. f SEM of laser structured porous MoCx with connected curved surface. g Transmission spectrum of 10 μm and 20 μm porous carbide thin films. Inset: simulated transmission curve of approximate carbide structure (inset) and simulated temperature profile in carbide unit cell. Incident light power Copt = 3 (3 kW m−2). h Simulated absorption of 500 nm incident light within a unit cell (1.6 μm) to illustrate the energy localization within the porous carbide structure. i Transmission intensity of different wavelengths in different approximate unit cell sizes

Under 3 sun illumination (3 kW m−2), enhanced solar-energy absorption generates a relatively higher temperature (60 °C) at the water-air interface compared to other photo-absorbing membranes such as carbonized wood (~40 °C)49, wood-CNT composite (~50 °C)50, graphite-carbon foam double layer structure (<40 °C)48 and etc. The evaporation rate and energy efficiency of solar-steam generation under different solar incident power is shown in Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 18. Such energy efficiency is comparable to the membranes mentioned above, yet lower than a recently reported nano-hierarchical gel having an extremely high efficiency up to 90%51. No specific thermal management is deployed to decrease the thermal loss, which can be improved by adding an insulation layer47,48 to further increase the energy efficiency. Nevertheless, the high-temperature-resilience of the carbide enables steam generation in harsh environments that could burn or destroy many other polymer-based membranes51. The MoCx reached ~160 °C within 60 s (Fig. 3d), under 11 sun exposure (Fig. 3d, inset). Near identical X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) of MoCx Mo_3d orbital before and after 11 sun exposure for one hour implies the carbide is stable in extreme solar radiation (Fig. 3d, inset), while a MoS2 membrane (Supplementary Fig. 19)52 is oxidized shown from its XPS Mo_3d orbital (Supplementary Fig. 20) in comparison. From the water transport analysis that we add to Supplementary Fig. 20 and Supplementary Table 2, dry-out is not happening at the membrane-water interface. Capillary force can drive water to the membrane surface. Carbide membrane shows a permeability of 1973.4 LMH bar−1, which falls to the range of membrane with pore size from hundreds of nanometers to micrometers53.

We employ density function theory (DFT) and finite differential time domain (FDTD) simulation to understand the solar-energy localization within carbide porous structure. Due to the lack of available reference data for experimentally measured optical properties of MoC1-x, we employ first principles simulations of the carbide dielectric constant and refractive index (Fig. 3e). The FDTD model is based on the SEM image in Fig. 3f, and a “gyroid-like” curved structure with variable unit cell is used to represent the porous carbide (Fig. 3g inset). The measured optical transmission for both 10 μm and 20 μm thick porous carbide membranes are shown in Fig. 3g, in good agreement with the computed optical transmission for the same wavelength range. All details of the DFT simulation and FDTD simulation are in the supporting information (Supplementary Fig. 21). Figure 3h is one example of optical absorption (500 nm incident light) projected onto the x–y plane in a unit cell (1.6 × 1.6 μm). Figure 3i shows the absorption intensity trend of different wavelength in different size carbide cells.

Discussion

In conclusion, we have developed a versatile approach for the synthesis of microporous ultrathin polycrystalline carbides (~10 nm crystallinity) with ultrathin “wall” structures (~10–20 nm), using lamellar templated metal ion (Mo, W, and Co) containing gelatin (metallo-hydrogel) and processing with a low-cost and fast CO2 laser cutter in ambient environment. The IR energy generates local high temperatures which induce a rapid carbon uptake to form carbon-deficient phases (MoCx, WCx, and CoCx), and sculptured interconnected curved structures during the sub millisecond “explosive” carbonization process. The laser-induced MoCx, as a conductive and refractory metallic material with hierarchical porosity (from microscale to nanoscale), was shown to be an appealing candidate for energy storage in lithium-based electrolyte (55 F g−1, discharged at 1 mV s−1). Direct patterned MoCx supercapacitor on PI tape shows a specific capacitance up to 20 mF cm−2 at a discharge rate of 1 mV s−1, and 2 mF cm−2 at 100 mV s−1. This work provides a general approach for a low cost, room temperature, high yield and exceptionally fast synthesis of transition metal carbides (Supplementary Table 3), which also enable large-scale devices and potentially roll-to-roll manufacturing. The non-decorated surface with less functional groups (–OH, –COOH) provide higher temperature resilience than surface-function-rich and chemical resilience (Table 2). The MoCx interdigitated electrodes used in conjunction with a Li-rich electrolyte (for lower freezing point) was demonstrated to function over a temperature range of −50 °C to 300 °C with no significant degradation while the laser-induced graphene decay in the same electrolyte. Laser sculpturing also provide hierarchical structure in multiple scale (ultrathin 2D like to 3D, Table 2), which also potentially bring intriguing properties and tunability in light and phonon transport. A post vacuum filtered MoCx membrane, exhibited effective solar-steam generation due to the size variable “gyroid-like” curved surface, which enhanced solar-energy harvesting. The direct write patterning and sculpturing process opens these materials up to a broader window of applications in flexible electronics, energy storage, energy harvesting, and water treatment applications.

Methods

Preparation of transition metallo-hydrogel

MoCl5, CoSO4, NiSO4, FeCl3, Zr(NO3)4, and Zn(NO3)2 (used as received from Sigma–Aldrich) were dissolved in deionized water, and WCl6 was dissolved in N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP, Sigma–Aldrich) with a concentration of 2 m (m is mass molality). The hydrogel was made by dissolving either gelatin, PVP or PEO with 60% wt concentration. Tetrabutyl titanate were mixed with NMP with a concentration of 2 m, which showed much lower solubility of gelatin (<5 wt%). Such Ti-NMP-gelatin mixture could only make suspension rather than uniform solution.

Synthesis of metal carbide by laser ablation

Metallo-gel precursor was spin coated onto glass and cured at 80 °C for 1 h to make a thin film, which was subsequently ablated by laser (IR 2 W; UV 1 W due to the limited of USB powered of UV laser. A commercial Universal VSL 2.30 was utilized to perform the laser ablation, with a CO2 laser tube and all built-in optics. Laser spot is focused on the top surface of spin-coated gel film, and the height of the sample is controlled by tuning the z-position of the supporting cutting table. Designed pattern is imported to a vector drawing software and engraved by communicating with the laser cutter as a printer. Unablated gel can be easily removed by rinsing the whole device in DI water for 1 min and air dry before test.

Materials characterization

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM, FEI Quanta 3D), Transmission electron microscopy (TEM, FEI Tecnai) were employed to study the morphology and structure. X-ray diffraction (XRD, Bruker D8) is performed to study the crystallinity, and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (CHI) is used to study the surface element component of samples. Co source is used in the powder diffraction X-ray test.

Electrochemistry test

Ag/AgCl was used as the reference electrode to study majorly carbide performance in different electrolytes. Magnesium acetate solution (~1 M, volumetric concentration), was purchased from BioUltra. NaCl (≥99%wt, Sigma–Aldrich) and LiCl (≥99.99% wt, Sigma–Aldrich) were dissolved in distilled water to make solution with concentration of 1 M (volumetric molarity). Concentrated sulfuric acid is diluted by deionized water to a volumetric molarity of 1 M. Linear sweep voltammetry, cyclic voltammetry, chronopotentiometry, and EIS impedance tests were performed by an electrochemistry workstation (Gamry Ref 600) with different modules. Powdery MoCx flakes are grinded with PAN (1 wt%) dissolved in N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP, Sigma–Aldrich) as binder, which is casted onto hydrophobic carbon paper (Toray Carbon Paper 060, Wet Proofed).

Fabrication of supercapacitor of carbides on PI tape

Mo-gelatin (2 m MoCl5, 60 wt%) hydrogel is spin coated onto Polyimide tapes to form a thin film, which is dried in the oven at 80 °C for 30 min. Gel-on-PI film is ablated by IR laser with 2 W power at a speed of 200 mm s−1. Interdigit structure is patterned with the geometry design using CAD interface. Li-rich electrolyte (21 m LiTFSI) is dissolved in DI water with 10% PVA, which is deposited onto the interdigit electrodes to assemble a functional supercapacitor. WCx and CoCx supercapacitor are fabricated via the same process using W-gelatin (2 m WCl6, 60 wt%) and Co-gelatin hydrogel (2 m CoCl2, 60 wt%).

Fabrication of ultrathin-TMC membrane

Laser-sculptured MoCx was scratched off subtracted, dispersed in DI water and ultrasonic for 2 h at 80 °C. The supernatant was vacuum filtered using a porous Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE, 47 mm diameter, 0.45 μm pore size, Fisher Scientific, Fair Lawn, NJ, USA) and dried in the air for 24 h. Same process is performed to vacuum filtrate carbide membrane onto Polyvinylidene (PVDF, 0.45 μm pore size, 47 mm diameter, Sterlitech Corp) and Polyethersulfone (PES, 0.45 μm pore size, 47 mm diameter, Sterlitech Corp) membrane filters.

Test of solar-thermal energy harvesting and steam generation

The experimental setup is equipped with a solar simulator (Newport 94023 A), and a balance, with data collection system (OHAUS, 420 g, with USB cable). The 47 mm membrane was exposed to solar illumination on the top of a baker (2 inch diameter) filled with DI water. IR camera was employed to record the temperature, with the balance to record mass loss.

Density functional theory simulation details for MoCx optical properties

All ab initio calculations were performed using the Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (version 5.4.4.18Apr1754). To obtain the dielectric tensor, the structure of MoC1-x was first relaxed to ensure all the forces on the ions were smaller than 0.01 eV Å−1. Then dielectric tensor was calculated using the independent particle approximation, and subsequently the local field effects were included using the random phase approximation. All calculations were performed using Perdew–Burke–Ernzerh (PBE55) version of generalized gradient approximation with projected-augmented wave potentials56,57 and a wave function energy cutoff of 400 eV; the Brillouin zone was sampled with, respectively, 1728 and 4096, k-points, to confirm convergence. In calculating the frequency-dependent dielectric tensor, 2000 frequency grid points were used, and the actual number of bands (1280) was carefully chosen such that a considerable number of empty bands was included in the calculation.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Oyama, S. T. (ed.) in The Chemistry of Transition Metal Carbides and Nitrides Ch. 1 (Springer, Netherland, 1996). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-1565-7

Seh, Z. W. et al. A two-dimensional molybdenum carbide (mxene) as an efficient electrocatalyst for hydrogen evolution. ACS Energy Lett. 1, 589–594 (2016).

Xu, C. et al. Large-area high-quality 2D ultrathin Mo2C superconducting crystals. Nat. Mater. 14, 1135–1141 (2015).

Li, J. S. et al. Coupled molybdenum carbide and reduced graphene oxide electrocatalysts for efficient hydrogen evolution. Nat. Commun. 7, 11204 (2016).

Zhao, X. et al. Edge segregated polymorphism in 2D molybdenum carbide. Adv. Mater. 31, 1808343 (2019).

Lukatskaya, M. R., Dunn, B. & Gogotsi, Y. Multidimensional materials and device architectures for future hybrid energy storage. Nat. Commun. 7, 12647 (2016).

Naguib, M., Mochalin, V. N., Barsoum, M. W. & Gogotsi, Y. 25th anniversary article: MXenes: a new family of two-dimensional materials. Adv. Mater. 26, 992–1005 (2014).

Mashtalir, O. et al. Intercalation and delamination of layered carbides and carbonitrides. Nat. Comm. 4, 1716 (2013).

Ghidiu, M., Lukatskaya, M. R., Zhao, M. Q., Gogotsi, Y. & Barsoum, M. W. Conductive two-dimensional titanium carbide ‘Clay’ with high volumetric capacitance. Nature 516, 78–81 (2014).

Anasori, B., Lukatskaya, M. R. & Gogotsi, Y. 2D metal carbides and nitrides (MXenes) for energy storage. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 16098 (2017).

Barsoum, M. W. The Mn+1AXn phases: a new class of solids: thermodynamically stable nanolaminates. Prog. Solid State C. 28, 201–281 (2000).

Khazaei, M. et al. Novel electronic and magnetic properties of two-dimensional transition metal carbides and nitrides. Adv. Fun. Mater. 23, 2185–2192 (2013).

Lukatskaya, M. R. et al. Cation intercalation and high volumetric capacitance of two-dimensional titanium carbide. Science 341, 1502–1505 (2013).

Eklund, P., Rosen, J. & Persson, P. O. Å. layered ternary Mn+1axn phases and their 2D derivative mxene: an overview from a thin-film perspective. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 50, 113001 (2017).

Gogotsi, Y. Chemical vapour deposition: transition metal carbides go 2D. Nat. Mater. 14, 1079–1080 (2015).

Geng, D. C. et al. Direct synthesis of large-area 2D Mo2C on in situ grown graphene. Adv. Mater. 29, 1700072 (2017).

Li, Z. Y. et al. Synthesis and thermal stability of two-dimensional carbide mxene Ti3C2. Mater. Sci. Eng. B-Adv. 191, 33–40 (2015).

Zang, X. et al. Laser induced molybdenum carbide-graphene composites for 3d foldable paper electronics. Adv. Mater. 30, 1800062 (2018).

Sarycheva, A. et al. 2D titanium carbide (mxene) for wireless communication. Sci. Adv. 4, eaau0920 (2018).

Bigi, A., Panzavolta, S. & Rubini, K. Relationship between triple-helix content and mechanical properties of gelatin films. Biomaterials 25, 5675–5680 (2004).

Xing, Q. et al. Increasing mechanical strength of gelatin hydrogels by divalent metal ion removal. Sci. Rep. 4, 04706 (2014).

He, M. H. & Qiu, H. H. Internal flow patterns of an evaporating multicomponent droplet on a flat surface. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 100, 10–19 (2016).

Ladet, S., David, L. & Domard, A. Multi-membrane hydrogels. Nature 452, 76–76 (2008).

Dai, H. J. et al. Multi-membrane hydrogel fabricated by facile dynamic self-assembly. Soft Matter 5, 1987–1989 (2009).

Hu, H. & Larson, R. G. Analysis of the effects of marangoni stresses on the microflow in an evaporating sessile droplet. Langmuir 21, 3972–3980 (2005).

Villers, D. & Platten, J. K. Coupled buoyancy and marangoni convection in acetone - experiments and comparison with numerical Simulations. J. Fluid. Mech. 234, 487–510 (1992).

Wang, F. et al. Nanometre-thick single-crystalline nanosheets grown at the water-air interface. Nat. Commun. 7, 10444 (2016).

Yan, H. et al. Hybrid metal-organic chalcogenide nanowires with electrically conductive inorganic core through diamondoid-directed assembly. Nat. Mater. 16, 349–355 (2017).

Cumberland, S. L. et al. Inorganic clusters as single-source precursors for preparation of Cdse, Znse, and Cdse/Zns nanomaterials. Chem. Mater. 14, 1576–1584 (2002).

Kappes, R. S. et al. A study of photothermal laser ablation of various polymers on microsecond time scales. + 3, 489 (2014).

Wilkinson, A., & Mcnaught, A. Iupac Compendium of Chemical Terminology (the “Gold Book”) (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, 1997).

Zang, X. et al. Self-assembly of large-area 2D polycrystalline transition metal carbides for hydrogen electrocatalysis. Adv. Mater. 30, 1805188 (2018).

Lin, J. et al. Laser-induced porous graphene films from commercial polymers. Nat. Commun. 5, 6714 (2014).

Nagakura, S. Study of metallic carbides by electron diffraction .4. cobalt carbides. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 16, 1213 (1961).

Harilal, S. S., Freeman, J. R., Diwakar, P. K. & Hassanein, A. Femtosecond laser ablation: fundamentals and applications. Springe. Ser. Opt. Sci. 182, 143–166 (2014).

Fernandes, C. M. & Senos, A. M. R. Cemented carbide phase diagrams: a review. Int. J. Refract. Met. H. Mater. 29, 405–418 (2011).

Johnson, G. K., Hubbard, W. N. & Storms, E. K. The enthalpies of formation of Mo2C(c) and Mo3C2(c) by fluorine bomb calorimetry. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 9, 1021–1026 (1977).

Predel, B. C-Mo (Carbon-Molybdenum): Datasheet from Landolt-Börnstein-Group IV Physical Chemistry· Volume 5b: “B-Ba-C-Zr” in Springermaterials https://doi.org/10.1007/10040476_643 (Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1992).

Halim, J. et al. Synthesis and characterization of 2D molybdenum carbide (mxene). Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 3118–3127 (2016).

Eklund, P., Beckers, M., Jansson, U., Högberg, H. & Hultman, L. The Mn+ 1axn phases: materials science and thin-film processing. Thin. Solid. Films 518, 1851–1878 (2010).

Zang, X., Zhou, Q., Chang, J., Liu, Y. & Lin, L. Graphene and carbon nanotube (CNT) in MEME/NEMS applications. Microelectron. Eng. 132, 192–206 (2015).

Jiang, Y. et al. Uniformly embedded metal oxide nanoparticles in vertically aligned carbon nanotube forests as pseudocapacitor electrodes for enhanced energy storage. Nano Lett. 13, 3524–3530 (2013).

Reddy, S. L., Endo, T. & Reddy, G. S. in Electronic (Absorption) Spectra of 3d Transition Metal Complexes , Advanced Aspects of Spectroscopy, Muhammad Akhyar Farrukh, IntechOpen (2012).

Miller, F. A. & Wilkins, C. H. Infrared spectra and characteristic frequencies of inorganic ions—their use in qualitative analysis. Anal. Chem. 24, 1253–1294 (1952).

Tiliakos, A., Ceaus, C., Iordache, S. M., Vasile, E. & Stamatin, I. Morphic transitions of nanocarbons via laser pyrolysis of polyimide films. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrol. 121, 275–286 (2016).

Mellor, J. W. in Modern Inorganic Chemistry. (Longmans, Green Co, 1912).

Tao, P. et al. Solar-driven interfacial evaporAtion. Nat. Energy 3, 1031–1041 (2018).

Ghasemi, H. et al. Solar steam generation by heat localization. Nat. Commun. 5, 5449 (2014).

Liu, H. et al. High-performance solar steam device with layered channels: artificial tree with a reversed design. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1701616 (2018).

Chen, C. et al. Highly flexible and efficient solar steam generation device. Adv. Mater. 29, 1701756 (2017).

Zhao, F. et al. Highly efficient solar vapour generation via hierarchically nanostructured gels. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 489–495 (2018).

Chen, W. et al. Quantum dots of 1T phase transitional metal dichalcogenides generated via electrochemical Li intercalation. ACS Nano 12, 308–316 (2017).

Fane, A. G., Fell, C. J. D. & Waters, A. G. The relationship between membrane-surface pore characteristics and flux for ultrafiltration membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 9, 245–262 (1981).

Kresse, G. & Furthmuller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for Ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Blochl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Acknowledgements

This work was performed in part at the Molecular Foundry, a User Facility supported by the Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. We gratefully acknowledge the computational resources from National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), a U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science User Facility operated under Contract No. DE-AC02-05CH11231. A few of authors get support from Berkeley Sensor and Actuator Center. We want to thank Dr. Anthony Straub from Grossman Group in Massachusetts Institute of Technology to help measure the permeability of carbide membrane. We specially thank Prof. Gang Chen from MIT to share facilities for solar-steam generation test, and Dr. Bruno Lorenzi from Prof. Chen’s group for training. The authors thank Dr. Morris Wang from Lawrence Livermore National Lab for inspiring discussions on ultrathin TMCs, Prof. Peng Tao and Prof. Tao Deng from Shanghai Jiao Tong university for facilities support to test the solar-steam generation and helpful discussions.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.Z. designed, performed most of the experiments, and analyzed the results. X.Z., L.L. and J.C.G. wrote the paper. M.F., M.W., B.L., Y.C., J.C., Y.X. and Z.W. helped with the experiments; P.A. helped with the AFM measurements; Z.F. performed the TEM analysis of materials; C.J. and T.Z. performed DFT simulation; C.J. performed Molecular Dynamics simulations, which are not presented in current version but is crucial to design the carbide-based electrochemical supercapacitor presented; Z.L. helped with the water transport analysis of carbide membrane; W.W. and X.D. helped with FDTD optical simulations and temperature profile modeling; J.N.H. and M.S. helped to revise the paper; the paper and figures were prepared with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information: Nature Communication would like to thank Hak Yong Kim and other, anonymous, reviewers for their contributions to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zang, X., Jian, C., Zhu, T. et al. Laser-sculptured ultrathin transition metal carbide layers for energy storage and energy harvesting applications. Nat Commun 10, 3112 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10999-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-10999-z

This article is cited by

-

Laser-induced jigsaw-like graphene structure inspired by Oxalis corniculata Linn. leaf

Bio-Design and Manufacturing (2022)

-

Laser-induced graphene for bioelectronics and soft actuators

Nano Research (2021)

-

Nanocarbon-Enhanced 2D Photoelectrodes: A New Paradigm in Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting

Nano-Micro Letters (2021)

-

Laser Synthesis and Microfabrication of Micro/Nanostructured Materials Toward Energy Conversion and Storage

Nano-Micro Letters (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.