Abstract

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide. Tumor suppressor genes remain to be systemically identified for lung cancer. Through the genome-wide screening of tumor-suppressive transcription factors, we demonstrate here that GATA4 functions as an essential tumor suppressor in lung cancer in vitro and in vivo. Ectopic GATA4 expression results in lung cancer cell senescence. Mechanistically, GATA4 upregulates multiple miRNAs targeting TGFB2 mRNA and causes ensuing WNT7B downregulation and eventually triggers cell senescence. Decreased GATA4 level in clinical specimens negatively correlates with WNT7B or TGF-β2 level and is significantly associated with poor prognosis. TGFBR1 inhibitors show synergy with existing therapeutics in treating GATA4-deficient lung cancers in genetically engineered mouse model as well as patient-derived xenograft (PDX) mouse models. Collectively, our work demonstrates that GATA4 functions as a tumor suppressor in lung cancer and targeting the TGF-β signaling provides a potential way for the treatment of GATA4-deficient lung cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), the leading cause of cancer-related deaths, is responsible for estimated 1.6 million deaths as of the year 20121,2. Lung adenocarcinoma is the most common type of NSCLC3, highlighting the urgent need for novel therapeutic approaches.

Tumor suppressor genes (TSGs) inhibit tumor formation and metastasis mainly through the induction of cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis, and/or senescence4. They achieve these biological impacts via regulating diverse cellular activities, including DNA damage responses, tumor angiogenesis, protein ubiquitination and degradation, mitogenic signaling, cell specification, differentiation, and migration5. Moreover, inactivation of TSG modulates tumor cells’ response to current therapies6,7.

Transcription factors (TFs), especially master TFs, play dominant roles in maintaining the phenotype of a particular tissue type by interacting with the super enhancers8. Not surprisingly, TFs frequently function as TSGs9,10,11,12. Despite of the importance of TFs in tumorigenesis and their impact on the response of tumor cells to treatment, a systemic assay of TSG TFs remains to be determined in lung cancer.

GATA4 belongs to the zinc finger transcription factor family which consists of six members from GATA 1 to GATA 6. The structure of GATA4 features family-specific two N-terminal transcription activation domains (TAD), two central zinc finger domains (ZF), a nuclear localizing signal (NLS) immediately C-terminal to ZF2, and a C-terminal region (CTR)13. GATA4 binds to the consensus sequence, A/TGATAA/G14, in a highly dynamic manner to regulate numerous target gene expression during the process of organogenesis15 and in response to environmental cues16,17. GATA4 is therefore considered as a pioneer modifier that opens up a closed chromatin to facilitate binding of TFs including itself to the target sites18. Moreover, GATA4 activity is subjected to the regulation by various types of post-translational modifications, including phosphorylation13,19, acetylation20,21, methylation22, and SUMOylation23. Not surprisingly, GATA4 is recognized as the critical controller for cell fate.

GATA4 plays a pivotal role during lung development. Missense mutation of GATA4 (V238G) causes abnormal lung structure and embryonic lethality in mice24. Clinical studies reported frequent hypermethylation of the GATA4 promoter in human lung cancer samples but not in paired normal lungs25,26,27. Despite of the fact that GATA4 is widely epigenetically silenced in lung cancer, the impacts of GATA4 silencing on tumorigenesis and corresponding cancer therapeutic strategies remain largely unexplored.

Here, we have performed a genome-wide screening of TFs to identify potential TSGs in lung cancer. We find that GATA4 is an essential TSG and further demonstrate that the hyperactivated TGF-β-TGFBRs-SMAD-Wnt signaling axis serves as potential target for treating GATA4-deficient lung cancer.

Results

GATA4 is an essential tumor suppressor in lung cancer

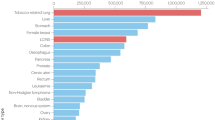

To systematically investigate the potential role of TFs in lung cancer, we individually transfected H23 cells, a lung cancer cell line harboring KrasG12C mutation, with 1530 siRNA sets (each set containing four different siRNAs towards single genes) targeting TFs on a genome-wide scale. Through this screening measured by cell growth assay, we identified 23 siRNA sets which significantly promoted H23 cell growth (cutoff = 1.5) (Supplementary Figure 1A, Supplementary Data 1). Interestingly, RNA-Seq data analyses showed that these genes were downregulated in human lung cancer (Supplementary Data 2). We then plotted the cell growth rates against relative gene expression in clinical samples and identified five candidates with most dramatic effects (Fig. 1a; Supplementary Data 3), among which GATA4 stood out as the top hit. To further validate our screening results, we individually knockdown these five genes in another lung cancer cell line H460 and found that knockdown of GATA4, BTBD11 or EOMES significantly enhanced the colony formation in soft agar (Supplementary Figure 1B).

GATA4 is an important tumor suppressor in lung cancer. a Scatterplot of relative growth rate against relative expression level. 10,000 H23 cells per well seeded in 96-well plate; siRNA transfected into individual wells. CCK8 value of a well 3 days post siRNA transfection was plotted against relative expression value of the corresponding gene in tumor (one replica). b Western blot analysis of GATA4 expression in cancerous and normal lung cell lines. c Lung cancer cells infected with lentivirus for ectopic expression of GATA4. Soft-agar colony forming ability was compared between lung cancer cell lines (A549, PC-9, and H460) ectopically expressing GATA4 and EGFP. Scale = 500 μm. d Statistics of soft-agar colony result shown in c (n = 3 per group). e Colony number of 10,000 A549i cells in the absence or presence of Dox checked 14 days after seeding in soft agar plate. Upper panel: statistics of the soft-agar colonies. Lower panel: representative pictures of A549i cells treated with or without 2 μg/mL of Dox (n = 3 per group, scale = 100 μm) (A549i is an engineered A549 clone harboring Dox inducible GATA4 expression gene element). f Soft-agar colony forming ability of stable H23 with GATA4 knockdown by shRNAs or control shRNA. Upper panel: statistics of soft-agar colony result of H23 knockdown with control or GATA4 targeting shRNAs. Lower panel: Representative pictures (n = 3 per group, scale = 50 μm). g Lsl-KRASG12D infected with recombinant lentivirus coexpressing Cre and CRISPR/CAS9 through nasal instillation. Lung tumor formation in KRASG12D/GATA4-/- mice compared to KRASG12D/TdTomato-/- mice 10 weeks post-infection. Scale = 200 μm. h Statistics of percentage of tumor area in the lung represented in g (n = 3 per group). i Schematics of intranasal instillation of retrovirus for forced expressing GATA4 in Dox inducible Tet-KRASG12C/CC10rtTA lung cancer mouse model (referred to as KC). j Pathology of lung tumor formation in KC mice infected with control (mCherry) or GATA4 expressing virus. Scale = 200 μm. k Statistics of tumor area per lung area (n = 3 per group). Bars are represented as mean ± SEM of the indicated number (n) of repeats. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 by Student’s t-test

Although GATA4 inactivation has been frequently reported in human lung cancer25,26,27, its impact upon lung tumorigenesis and therapeutics remain largely unknown. We therefore focused on GATA4.Western blot analysis showed that GATA4 expression in human lung cancer cell lines including NCI-H226, NCI-H23, NCI-H460, PC9, and A549 cells was consistently lower than normal lung epithelial cell lines including HSEAC37, HSEAC2KT, and HBEC30 (Fig. 1b). Ectopic GATA4 expression significantly inhibited soft-agar colony formation in A549, PC-9, and H460 cells (Fig. 1c, d, Supplementary Figure 1C and 1D). We further established A549 stable cell line with doxycycline (Dox)-inducible GATA4 (referred to as A549i, Supplementary Figure 1E and 1F). We found that Dox treatment significantly inhibited soft-agar colony formation and decreased cell growth of A549i cells (Fig. 1e; Supplementary Figure 1G). Conversely, GATA4 knockdown dramatically enhanced the colony formation capabilities of H23 and H226 cell in soft agar (Fig. 1f, Supplementary Figure 1H, 1I, 1J and 1K). These data clearly supported the tumor suppressive function of GATA4 in vitro.

We went on to confirm tumor suppressor function of GATA4 in vivo using transgenic lung cancer mouse model. Previous study has established the simultaneous knockout of a target gene and activation of mutant KRAS in the lung epithelia in lsl-KrasG12D transgenic mice using recombinant lentivirus coexpressing Cre and CRISPR/CAS928. Following this protocol, we intranasally delivered lentiviruses targeting either TdTomato (serving as negative control) or GATA4 into lsl-KrasG12D mice. In stark contrast to control group, we detected notable lung tumor nodules in 3 out of 4 mice post 10 weeks of lenti-sgGATA4 nasal inhalation (referred to as KG mice for KrasG12D/GATA4-/-) (Fig. 1g, h, Supplementary Figure 1L), further supporting the tumor suppressive function of GATA4 in vivo.

We further constructed a retrovirus for Dox-inducible expression of GATA4 (mCherry serves as the negative control) in the lung compartment of TetO-KrasG12C/CC10rtTA bitransgenic mice (referred to as KC) (Supplementary Figure 1M and 1N). KC mice developed lung cancers with diffused bronchioloalveolar carcinoma (BAC) features after fed with a Dox diet for three weeks, whereas remained tumor-free and healthy when fed with normal diet29 (Supplementary Figure 1O). Retrovirus encoding TetO-GATA4 was delivered into the lung epithelial compartments through nasal instillation for Dox inducible expression as reported earlier30 (Fig. 1i). Reverse-transcription PCR analyses confirmed the ectopic GATA4 expression in lung tissues post 3 days of Dox treatment (Supplementary Figure 1P). As expected, the KC mice infected with control virus developed lung adenocarcinoma after 3 weeks of treatment with Dox (Fig. 1j). In contrast, retroviral expression of GATA4 significantly inhibited tumor formation (Fig. 1j, k). Similar result was obtained in TetO-EGFR T790M/Ex19del/CC10rtTA mice31 (Supplementary Figure 1Q and 1R).

Ectopic expression of GATA4 induces lung cancer cell senescence

We next investigated how GATA4 influenced lung cancer cell growth. When GATA4 was overexpressed, A549 cells exhibited enlarged and flattened morphology, a typical feature of cell senescence (Fig. 2a). Indeed, cell senescence was confirmed through senescence-associated β-galactosidase staining (Fig. 2b, c). This senescent phenotype was also observed in Dox-treated A549i cells (Fig. 2d). Consistently, we found that significantly higher portion of cells were arrested at G0/1 when expressing GATA4 (Supplementary Figure 2A).

Ectopic GATA4 expression induces lung cancer cell senescence. a Microphotograph of A549 cells infected lentivirus overexpressing GATA4. Red arrow-head highlighted the senescent cells. Scale = 100 μm. b β-galactosidase staining of A549 cells infected with GATA4 or EGFP expressing lentivirus. Representative pictures were shown. Scale = 100 μm. c, d Statistics of β-Galactosidase staining of A549 cells ectopically expressing GATA4 through lentivirus infection (c) or Doxycycline treatment of A549i cells (d) (n = 3 per group). e Western blot analysis of Doxycycline-inducible GATA4 expression in stable cell lines of H460, EKVX, and Hop62. f β-Galactosidase staining of indicated cell lines before and after GATA4 expression. g Statistics of f (n = 3 per group). h Western blot analysis of p15INK4b expression in GATA4-expressing A549 cells. i β-galactosidase staining of GATA4-expressing A549 knockdown with control or CDKN2B-targeting shRNAs (n = 3 per group). Bars are represented as mean ± SEM of the indicated number (n) of repeats. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 by Student’s t-test

To confirm whether GATA4-induced senescence was common in lung cancer cells, we generated lung cancer cell lines (H460, EKVX, and HOP62) for Dox-inducible expression of GATA4 (Fig. 2e). We found that GATA4 expression significantly induced senescence (Fig. 2f, g).

Western blot analysis revealed that ectopic GATA4 expression led to the inhibition of pro-growth signals including phospho-ERK and phospho-AKT, but upregulation of PTEN, an anti-growth signal (Supplementary Figure 2B). Cellular senescence is a stress response that accompanies a stable exit from the cell cycle; it is commonly induced by cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors (CKI). Western blot analysis showed no significant change of p53, p21, p27, p14ARF, or p16INK4a level before and after GATA4 expression in A549 cells (Supplementary Figure 2C and 2D). Instead, p15INK4b, another CKI for eliciting senescence, showed notable increase after GATA4 expression (Fig. 2h). However, knockdown of p15INK4b expression with shRNAs failed to rescue cell from GATA4-induced senescence (Fig. 2i; Supplementary Figure 2E), suggesting that GATA4 induced senescence in lung cancer cells independently of canonical pathway.

GATA4 induces cell senescence through downregulation of Wnt-7b signaling

As typical executors of senescence are not implicated in GATA4-induced senescence, we went on to determine the underlying signaling events. We ruled out two classical GATA4 transcriptional targets, NKX2.5 and SMARCD332, as the effectors of GATA4-induced senescence (Supplementary Figure 3A-3F).

Recently, Elledge and colleagues reported that GATA4 elicited cellular senescence through NF-κB signaling pathway and featured senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) in IMR90 fibroblast33. However, we did not detect obvious upregulation of SASP cytokines in lung cancer cells ectopically expressing GATA4 (Supplementary Figure 3G). Moreover, inhibition of NF-κB activity either through targeting RELA with shRNAs or treatment with inhibitor did not result in lung cancer cell senescence (Supplementary Figure 3H, 3I, 3J, 3K, and 3L), suggesting that NF-κB pathway is not involved in this process.

We then performed ChIP-seq analysis and found no typical senescence-related genes (Supplementary Data 4, 5 and 6). We further did RNA-seq and found that 302 genes were significantly upregulated (>2-fold change, p < 0.05, Supplementary Data 7) and 530 genes were downregulated (<0.5-fold change, p < 0.05, Supplementary Data 8) in cells with GATA4 expression induction. No specific pathway known to directly regulate senescence was identified in KEGG pathway analysis (Supplementary Data 9 and 10) or Gene Ontology enrichment analysis (Supplementary Data 11 and 12).

Earlier reports demonstrated that the downregulation of Wnt signaling triggered senescence34,35. In our RNA-seq, we noticed that WNT7B expression level were downregulated in A549 cells ectopically expressing GATA4 (Supplementary Data 8). We suspected that GATA4-mediated downregulation of WNT7B may result in cell senescence. Real-time PCR analysis confirmed downregulation of WNT7B mRNA level in A549 cells with GATA4 expression (Fig. 3a, b). We found that GATA4 expression led to the downregulation of Wnt signaling, indicated by the decrease of β-Catenin transcriptional activity (Fig. 3c). Western analysis found that GATA4 expression led to the downregulation of Wnt pathway target genes including c-Myc and CCND1 (Fig. 3d). Importantly, we found that knockdown of WNT7B was able to induce senescence in A549 cells (Fig. 3e), and this senescence was rescued by ectopic expression of shRNA-resistant WNT7B (Fig. 3e, f, Supplementary Figure 3M). We also generated A549 cells with Dox-inducible expression of shWnt7b (referred to as Tet-shWnt7b). Downregulation of WNT7B through Dox treatment in A549-Tet-shWnt7b resulted in senescence (Fig. 3g, Supplementary Figure 3N). Critically, GATA4-induced senescence can be rescued by WNT7B overexpression (Fig. 3h). These data identified Wnt-7b as the critical mediator of GATA4-induced senescence.

GATA4 induces lung cancer cell senescence by downregulating WNT7B. a and b WNT7B expression level in A549 cells ectopically expressing GATA4 through lentivirus infection (a) or Doxycycline treatment of A549i cells (b) (n = 3 per group). c TOP-FLASH analysis of GATA4 expressing A549 cells (n = 6 per group). d Western blot analysis of c-Myc and cyclin D1 in A549i cells in the absence or presence of 2 μg/mL of Dox. e β-Galactosidase staining of A549 cells expressing WNT7B targeting shRNA (middle panel) and rescued by shRNA-resistant WNT7B (right panel) (scale bar 100 μm). f Statistics of e (n = 3 per group). g β-Galactosidase staining of A549 expressing Dox-inducible shRNA targeting WNT7B (A549 tet-shWNT7B) in the absence or presence of 2 μg/mL of Dox (n = 3 per group). h β-Galactosidase staining of A549i in the absence or presence of 2 μg/mL of Dox and rescued by Wnt-7b expression (n = 3 per group). i Impact of shRNA targeting CTNNB1 mRNA on induction of senescence in A549 cells (n = 3 per group). j β-Galactosidase staining of A549 cells treated with ICG-001 and XAV939 at indicated concentration (n = 3 per group). k qRT-PCR analysis of MMP7 expression of in A549i cells in the absence or presence of 2 μg/mL of Dox (n = 3 per group). l β-Galactosidase staining of A549 cells knockdown with shRNA targeting MMP7 mRNA (n = 3 per group). Bars are represented as mean ± SEM of the indicated number (n) of repeats. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 by Student’s t-test

Wnt ligands were known to elicit a canonical signaling pathway (the β-catenin-dependent pathway), as well as non-canonical signaling pathways (β-catenin-independent); many Wnt ligands were found to elicit non-canonical pathways36. We asked whether the GATA4-induced senescence resulted from the downregulation of WNT7B was mediated by the canonical β-Catenin-dependent pathway. Knockdown of CTNNB1 did not result in senescence (Fig. 3i; Supplementary Figure 3O). Likewise, treatments with β-Catenin inhibitors, XAV93937 and ICG-00138, respectively, did not lead to increased senescence (Fig. 3j; Supplementary Figure 3P), suggesting that canonical Wnt signaling is not responsible for GATA4-induced lung cancer cell senescence.

Downregulation of MMP7 expression is known to effectively induce cell senescence39,40. MMP7 is a transcriptional target of β-Catenin. Given that canonical Wnt signaling is not responsible for GATA4-induced senescence, MMP7 should not be involved in mediating GATA4-induced senescence. In our RNA-seq data, we found MMP7 expression was downregulated by GATA4 (Supplementary Data 8). We validated this downregulation in Dox-treated A549i cells through qRT-PCR (Fig. 3k). Importantly, knockdown of the MMP7 did not increase senescence in A549 cells (Fig. 3l; Supplementary Figure 3Q). These results demonstrated that GATA4-induced senescence caused by downregulation of WNT7B is not mediated through the canonical Wnt signaling pathway.

Adams and colleagues have reported the mechanism underlying senescence elicited by downregulation of Wnt signaling: GSK3β downstream of WNT7B phosphorylates HIRA to drive translocation of HIRA to PML body to form complex with ASF1a, and thus initiating senescence process34. Since GATA4 induces lung cancer cell senescence through downregulating WNT7B, we checked PML-HIRA colocalization signal triggered by ectopic expression of GATA4. We detected robust PML-HIRA colocalization signal in A549 cells with WNT7B knockdown by shRNA in comparison to intact A549 cells (Supplementary Figure 3R). Interestingly, we found that GATA4 expression resulted in similar level of PML-HIRA colocalization to that found in WNT7B knockdown (Supplementary Figure 3R and 3S), suggesting that mechanism revealed by Adams and colleagues may apply to GATA4 induced senescence in lung cancer cells.

TGF-β2 mediates GATA4-induced senescence upstream of Wnt-7b

We carefully analyzed ChIP-seq data and excluded the possibility of direct binding of GATA4 to WNT7B promoter (Supplementary Data 4). We then asked how GATA4 inhibited WNT7B expression. Our RNA-seq data analyses showed that TGF-β2 expression was downregulated in A549 cells expressing GATA4 (Fig. 4a, b). The TGF-β signaling pathway has been reported to be engaged in cross-talk with and upregulating the Wnt signaling41,42. We went on to test whether TGF-β2 is a critical mediator of GATA4-induced senescence. Interestingly, knockdown of TGFB2 with shRNAs induced senescence (Fig. 4c). This senescence is effectively rescued by ectopic overexpression of shRNA-resistant TGFB2 (Fig. 4c, d, Supplementary Figure 4A). This is also confirmed in A549 cells harboring Dox-inducible shRNA-targeting TGFB2 (Fig. 4e, Supplementary Figure 4B). Importantly, we found that overexpression of TGFB2 was able to rescue GATA4-induced senescence (Fig. 4f). We also supplemented Dox-treated A549i cells with recombinant TGF-β protein and found that TGF-β protein rescued GATA4-induced senescence of A549 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4g), supporting that TGF-β protein itself prevented GATA4-induced senescence in lung cancer cells.

TGF-β2 mediates GATA4-induced senescence upstream of Wnt-7b. a and b qRT-PCR analysis of TGFB2 expression in GATA4 overexpressing A549 cells through lentivirus infection (a) or Doxycycline treatment of A549i cells (b) (n = 3 per group). c β-Galactosidase staining of A549 cells with TGFB2 knockdown (middle panel) and rescued by shRNA-resistant TGFB2. d Statistics of c (n = 3 per group). e β-Galactosidase staining of A549 expressing Dox-inducible shRNA targeting TGFB2 (n = 3 per group). f β-Galactosidase staining of A549i in the absence or presence of 2 μg/mL of Dox and rescued by TGFB2 expression (n = 3 per group). g β-Galactosidase staining of A549i cells in the absence or presence of 2 μg/mL of Dox and rescued with recombinant TGF-β protein at indicated concentration (n = 3 per group). h β-Galactosidase signal in A549 cells knockdown of TGFBR1 and TGFBR2 (n = 3 per group). i β-Galactosidase signal of A549 cells with SMAD2 knockdown (middle panel) and rescued by shRNA-resistant SMAD2 (right panel). j β-Galactosidase staining of A549 cells with SMAD4 knockdown (middle panel) and rescued by shRNA-resistant SMAD4 (right panel) (n = 3 per group). k WNT7B expression level in A549 cells with knockdown of TGFBR1, TGFBR2, SMAD2, or SMAD4, respectively (n = 3 per group). Bars are represented as mean ± SEM of the indicated number (n) of repeats. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 by Student’s t-test

TGF-β2 binds to TGFBR2, which then forms a complex with TGFΒR1, and the complex then phosphorylates R-SMADs, enabling the formation of a complex with SMAD4 that can enter the nucleus to transcribe target genes43. We found that knockdown of either TGFBR1 or TGFBR2 promoted senescence in A549 cells (Fig. 4h; Supplementary Figure 4C). We also systemically tested the role of canonical SMADs including SMAD2, SMAD3, and SMAD4 in GATA4-induced senescence. We found that knockdown of either SMAD2 or SMAD4 increased senescence (Fig. 4i, j; Supplementary Figure 4D).

We went on to test whether TGF-β2 signaling controlled Wnt-7b expression. Interestingly, we found that knockdown of TGFΒR1, TGFΒR2, SMAD2, or SMAD4 resulted in downregulation of WNT7B mRNA levels (Fig. 4k). Together, these data showed that TGF-β2 functioned upstream of Wnt-7b in mediating GATA4-induced senescence of lung cancer cells.

Of note, we found that GATA4 knockdown or overexpression did not significantly impact epithelial–mesenchymal transition of lung cancer cells in vitro and in vivo (supplementary Figure 4E, 4F, 4G, 4H, and 4I), consistent with earlier reports that TGFBR-SMAD signaling axis affect the senescence44.

GATA4 downregulates the TGFB2 mRNA level through miRNAs

We did not detect GATA4 binding to the TGFB2 promoter region in ChIP-seq analysis (Supplementary Data 4). In our ChIP-seq data we found promoter segments of 14 miRNA with potential to target TGFB2 mRNA (Fig. 5a). The detailed predicted targeting properties of the mature miRNAs targeting TGFB2 mRNA were listed in Supplementary Data 13. Four miRNAs (miRNA-32, miRNA-301b, miR-320a, and miR-590) were consistently upregulated in A549 cells expressing GATA4 (Fig. 5b). ChIP-PCR experiment showed the enrichment for the promoter regions of these four miRNA genes in the GATA4 immunoprecipitated DNA from GATA4 expressing A549 cells (Fig. 5c). Importantly, overexpression of each of these four miRNAs individually caused downregulation of the TGFB2 mRNA level (Fig. 5d). Conversely, we blocked the function of these four miRNAs with a microRNA sponge construct45, and found this sponge construct efficiently rescued GATA4-induced senescence in A549 cells (Fig. 5e; Supplementary Figure 5A). These data clearly showed that miRNAs (miRNA-32, miRNA-301b, miR-320a, and miR-590) upregulated by GATA4 played an important role in mediating GATA4-induced senescence.

GATA4 downregulates the TGFB2 mRNA level through multiple miRNAs. a Schematics of targeting sites on TGFB2 mRNA recognized by 14 miRNAs. b Relative expression level of miRNAs before and after GATA4 overexpression in A549i (through 2 μg/mL of Dox treatment) and A549 cells (through lentivirus infection) (n = 3 per group). c qPCR analysis of promoter fragment of designated gene from DNA samples prepared from control IgG or anti-FLAG (for pulldown GATA4) DNA samples. Quantity of GATA4 bond DNA was normalized by the value in control IgG-treated samples (n = 3 per group). d TGFB2 mRNA level in A549 cells overexpressing miR-32, miR-301b, miR-320A, or miR-590, respectively (n = 3 per group). e β-Galactosidase signal in GATA4 overexpressing A549 cells in the absence or presence of microRNA sponge (n = 3 per group). Bars are represented as mean ± SEM of the indicated number (n) of repeats. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 by Student’s t-test

GATA4-TGF-β2-Wnt-7b signaling axis is clinically relevant

Our above data have shown that GATA4 expression downregulated TGFB2 and the ensuing downstream WNT7B signaling in A549 lung cancer cell line. This was confirmed in H460 cells (Supplementary Figure 6A). Conversely, knockdown of GATA4 expression level upregulated TGFB2 and WNT7B transcription in lung cancer cell line H226 (Fig. 6a), supporting that GATA4-TGF-β2-Wnt-7b signaling axis is common to lung cancer cells. We also found significant negative correlation of expression level between GATA4 and TGFB2 and between GATA4 and WNT7B among non-manipulated lung cancer cell lines and normal lung epithelial cell lines (Supplementary Figure 6B).

The GATA4-TGF-β2-Wnt-7b signaling axis is clinically relevant. a qRT-PCR analysis of TGFB2 and WNT7B expression level in H226 cell line with GATA4 knockdown (n = 3 per group). b GATA4 expression level in lung cancer samples and normal lung tissues. c Kaplan–Meier survival curve of GATA4-high and GATA4-low lung cancer patients (Cox log-rank test, p = 0.019). d Reverse correlation of expression level of GATA4 versus TGF-β2 and Wnt-7b in clinical lung cancer samples downloaded from TCGA. e Expression pattern of GATA4 versus TGF-β2 and Wnt-7b in driver mutation positive samples. EGFR mutation positive: Upper panel; Kras mutation positive: middle panel; EML4-ALK mutation positive: lower panel

In order to validate the clinical relevance of our findings, we searched database from Oncomine and found that the GATA4 mRNA level was significantly lower in lung cancer samples than paired normal tissues (Fig. 6b), consistent with earlier reports that the promoter region of GATA4 was methylated in 67% of lung cancer samples25. Moreover, a higher expression level of GATA4 was associated with longer overall survival in comparison to those with lower expression (Fig. 6c).

Our model predicts that GATA4 expression level is inversely correlated with those of TGFB2 and WNT7B in lung cancer. In order to find supporting evidence in clinical samples for our model, we searched the expression data for GATA4, TGFB2, and WNT7B in lung adenocarcinoma patients from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). We were able to download normalized gene expression profile from https://confluence.broadinstitute.org/display/GDAC/Download (lung adenocarcinoma, n = 576) and used log2 value to represent gene expression in each sample. In this system, an expression value of 0 means no expression; a value of 2 as very low expression; and 20 as very high expression.

With this dataset, we were able to check the relationship of expression between GATA4, TGFB2, and WNT7B. To our surprise, majority of adenocarcinoma samples presented low GATA4 expression and high TGFB2 and WNT7B expression (Fig. 6d). Due to unbalanced sample distribution (not enough GATA4-high lung cancer samples), we were not able to calculate the significance in correlation test. However, this actually fitted our conclusion more favorably: GATA4 is inactive and at the same time WNT7B and TGFB2 is hyperactive in lung cancer cells.

Mutant EGFR, Kras, and EML4-ALK are critical driver oncogenes in lung cancers. We further checked pattern of expression of GATA4 versus TGFB2 and WNT7B in patients positive for mutations in these genes. We found that the pattern was highly similar in sub-cohorts of patients positive for mutation in EGFR, Kras and EML4-ALK respectively (Fig. 6e). Of note, we found very similar patterns in lung squamous cell carcinomas (Supplementary Figure 6C).

Taken together, these data suggest that GATA4 is frequently downregulated in lung cancers and the TGFB2-WNT7B signaling in these samples are activated.

TGFBR1 is a potential target for GATA4-deficient lung cancer

Kras mutation positive lung cancer are resistant to therapies currently available in clinic. We went on to test our findings on this type of lung cancer. Our data has shown that TGFB2-WNT7 signaling axis is hyperactivated in GATA4-deficient lung cancer cells. We asked whether this axis can be employed for treating GATA4-low lung cancers. Potent inhibitors targeting TGFBRs are now under clinical trial for cancer therapy46. Among TGFBR inhibitors commercially available, SB525334 is most potent in inhibiting TGFBR-SMAD2 signaling and cell proliferation (Supplementary Figure 7A, 7B and 7C). Moreover, SB525334 at achievable serum concentration led to significant senescence47 (Supplementary Figure 7D and 7E).

We have previously shown that blocking MEK1/2 is partially effective in shrinking mutant Kras-driven lung cancer48. Interestingly, we found that SB525334 synergized with an FDA approved MEK1/2 inhibitor, Trametinib, to control H23 cell growth (Fig. 7a). Similar synergy was observed in PC-9 cells with EGFR mutation and low GATA4 expression (Fig. 7b, expression level of GATA4 in Fig. 1b). Although SB525334 showed no synergy with Trametinib in eliciting apoptosis, it did synergize with Trametinib in inducing senescence (Supplementary Figure 7F and 7G).

TGFBR1 is a potential target for GATA4-deficient lung cancer. a and b 5000 cells per well seeded in 96-well plates. Cells were treated with SB525334 (2 μM) and/or trametinib (2 μM). CCK8 value were checked 3 days after drug treatment. a For H23 and b for PC9 (n = 3 per group). c SB525334 (10 mg/kg/day) synergizes with trametinib (10 mg/kg/day) to shrink lung tumor in KRASG12D/GATA4-/- mice. MRI image of lung of pre-treatment (left panel) and post-treatment (middle panel) of lung cancer bearing mice (PreRx and PostRx); β-Galactosidase staining of lung section of post-treatment mice (right panel). Scale = 100 μm. d Statistics of lung tumor burdens recorded in MRI (n = 4 per group). e Statistics of senescence in tumor shown (c) (n = 4 per group). f, g, h and i The tumor sizes and weights of PDX tumors treated with TGFBR inhibitor (SB525334, 10 mg/kg/day), Cisplatin (5 mg/kg, once a week), or combination. SH3166: GATA4-low PDX; SH3a: GATA4-high PDX (n = 6 per group). j Model of how GATA4 regulate TGF-β2 and Wnt-7b signaling and cellular senescence. See text for details. Bars are represented as mean ± SEM of the indicated number (n) of repeats. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 by Student’s t-test

We went on to treat GATA4-deficient lung cancer through targeting TGFBR1 using transgenic mouse models. We generated a cohort of lung cancer-bearing mice through intranasal delivery of Lenti-sgGATA4 into lsl-KrasG12D mice (referred to as KG mice, mentioned in Fig. 1g) and randomized them for treatments with SB525334, Trametinib, and SB525334/Trametinib combination for 2 weeks. We found that SB525334 treatment alone showed no significant treatment effect. However, Trametinib exhibited no significant treatment effect on KG mice, suggesting that GATA4 deficiency blunted therapeutic effect of MEK1/2 inhibition. Importantly, we found dramatic tumor shrinkage in mice treated with combined SB525334 and Trametinib treatment (Fig. 7c, d). Interestingly, we found that while either SB525334 or Trametinib elicited low level senescence in tumor tissues, combinational therapy elicited strong senescence signal (Fig. 7c–e).

To recapitulate the clinical setting, we tested treatment effect of TGFBR1 inhibitor on PDX mouse models. We collected surgically resected lung tumor nodules and inoculated them on nude mice. Western analysis showed both high and low GATA4 expression, respectively, in our samples (Supplementary Figure 7H). We found that Kras was wildtype in both GATA4-high (SH3a) and GATA4-low cancers (SH3166) (Supplementary Figure 7I and 7J). Consistent with our model, we found that SH3a had lower TGFB2 and Wnt7B expression level while SH3166 has higher TGFB2 and Wnt7B (Supplementary Figure 7K). As we did not expect Kras wildtype lung cancers responsive to Trametinib treatment, we chose to test whether SB525334 can synergize with cisplatin, the standard chemotherapeutics currently used in lung cancer clinic. We then grew these tumors in nude mice and treated them with vehicle, cisplatin, SB525334, or combination of cisplatin/SB525334. We found that cisplatin was partially effective in shrinking both GATA4-high and GATA4-low lung cancer PDX tumors, while SB525334 alone was not effective in either group (Fig. 7f–h). Importantly, while SB525334 did not obviously synergize with cisplatin in GATA4-high PDX samples (Fig. 7h, i), GATA4-low samples were highly sensitive to combinational treatment (Fig. 7f, g).

Taken together our data, we showed that GATA4 is frequently inactivated in lung cancer cells. GATA4 expression leads to upregulation of miRNAs (miRNA-32, miRNA-301b, miR-320a, and miR-590) targeting TGFB2, thus downregulating TGFB2 and ensuing downstream WNT7B signaling pathway to trigger cell senescence. GATA4 inactive lung cancers tend to have hyperactive TGB2-WNT7B signaling axis. Thereby, effective inhibitors targeting this signaling axis could potentially be employed for treating GATA4-deficient lung cancer patients. We have summarized our findings in Fig. 7j.

Discussion

We here performed a genome-wide screening of TSG TFs in lung cancer and identified GATA4 as an important tumor suppressor. Ectopic GATA4 expression results in lung cancer cell senescence. Mechanistically, we showed that GATA4 upregulated multiple miRNAs to downregulate the level of TGFB2 mRNA. TGF-β2 signals through TGFBR1, TGFBR2, SMAD2, and SMAD4 to upregulate WNT7B mRNA expression in lung cancer cells. By downregulating TGFB2 level via miRNAs, GATA4 decreases expression of WNT7B to induce senescence in lung cancer cells. Tumor suppressive function of GATA4 was further confirmed in transgenic mouse models for lung cancer in vivo. Our findings were clinically relevant. Moreover, we showed that TGFBR1 inhibition could suppress the malignant progression of GATA4-deficient lung cancer.

The GATA zinc finger transcription factor family consists of six members (GATA1–6). Each member has two ZF and binds to the 5′-(A/T)GATA(A/G)-3′ DNA consensus sequence in genomic DNA49. Members of this family are involved in many biological activities, and dysfunctions related to these proteins have been found in human diseases50. GATA4 plays a critical role in both cardiac49 and lung development24,51. Mice with a heterozygous deletion mutation (exon 2 deletion) of GATA4 show pulmonary defects including dilated distal airways and patches of thickened mesenchyme51. Frequent hypermethylation of the GATA4 promoter in majority of lung cancer samples but not in normal human lung tissues has been reported25,26,27. However, the impact of GATA4 silencing upon lung tumorigenesis and patients’ response to therapies remains largely unexploited. Our current work shed light on these important questions.

Stephen Elledge and colleagues have recently shown that GATA4 was stabilized by ATM and ATR to activate NF-κB and induce fibroblast senescence33. However, those critical features of senescence in that report were not detectable in our system. We reason this could be due to different tissue types and/or stress-specific conditions.

We further show that loss-of-function of GATA4 blunts cancer cells’ response to treatment of MEK1/2 inhibitors. It could be attributable to hyperactive TGFβ signaling in GATA4-deficient lung cancer. TGFβ signaling has been shown to confer drug resistance in lung cancer cells through activating MEK-ERK pathway52 or cancer stem cell property53. Both mechanisms as well as the activation of other potential oncogenes could blunt treatment effects of MEK1/2 inhibitors.

As GATA4 inactivation was reported in more than half of all clinical lung cancer cases, special attention should be paid to the status of GATA4 function for precision medicine for lung cancer patients. Phosphorylated TGFBRs, SMAD2, or SMAD4 could serve as biomarkers for the pathway activation. However, monitoring protein phosphorylation could be challenging in routine clinical practice, like immunohistochemistry (IHC), due to the time-lag in tumor sample collection during surgery and therein dephosphorylation of proteins. Moreover, IHC is less quantitative in nature, rendering it difficult to set the valuable standard. Other alternatives could be through monitoring mRNA expression of TGFβ or WNT7B.

TGF-β-signaling pathway plays a critical role in inducing regulatory T cells54,55,56,57. Senescent cancer cell recruits several types of immune effectors to the tumor region58,59. Inhibition of TGF-β-signaling pathway is, therefore, expected to enhance anti-tumor effect by activation of immune system60,61,62. Currently, plethora of inhibitors targeting the TGF-β-signaling pathway are in preclinical or clinical development46. Therapeutic intervention of TGF-β signaling should be considered as a choice for combination with current modalities63.

The TGFBR1 inhibitor, SB525334, efficiently inhibited lung cancer cell growth in vitro47. However, the in vivo effect was largely limited in transgenic lung cancer mouse model. We reason that several factors might be responsible for this discrepancy. First, lung epithelial cells must overcome tumor suppressing obstacles through mutation or silencing expression of tumor suppressor genes before they are transformed. As a result, the tumor nodules in autochthonous lung cancer mouse model are a complex mixture of highly heterogenous population of tumor cells in terms of gene mutation. Imaginably, there exist quite some clones that are de novo resistant to TGFBR1 inhibitor treatment. This could explain that while senescence was positive in a portion of cells in tumor nodules, the tumor shrinkage was limited. However, we cannot exclude the possibility that the relative insensitivity of in vivo tumor cells to SB525334 treatment was due to the difficulty of drug to reach tumor nodules. It has been reported that alteration of the function of vascular system and thereby the osmotic pressure within tumor nodules renders anticancer drug difficult to reach tumor tissues64, like that reported for mitomycin C65.

Methods

Animal care and use

All mice were housed in a pathogen-free environment in Jinan University and Institute of Biochemistry and Cell Biology, Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences, respectively. All experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Committee for Animal Care and Use at Jinan University, respectively, and Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, respectively. All animal work was performed in accordance with the approved protocol. PDX treatment was carried out as we reported earlier66. The CC10-rtTA; TRE-KrasG12C mice were sacrificed after 1 month of Dox diet feeding, while the CC10-rtTA; TRE-EGFR-TD mice were sacrificed after 3 months of feeding when the mice showed obvious panting phenotype. For IHC, mouse lung was inflated with 10% neutral buffered formalin solution (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) and incubated overnight. Paraffin embedded lung tissue was cut into 5 μm slices for immunohistochemical staining.

For the single-dose virus delivery experiment, all the littermates of double transgenic mice were randomly divided into two groups of 3–4 mice. GATA4 or mCherry retroviruses were delivered to mouse lung via nostril inhalation. After 1 week of recovery, all the experimental mice were fed with Dox containing food until the day of sacrifice. Mouse lungs were collected for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. For quantification of tumor burden in the CC10-rtTA; TetO- KrasG12C mice, we calculated the total size (mm2) of all the tumor regions in H&E sections under a microscope. For the CC10-rtTA; TetO-EGFR-TD mice, we counted the number of visible tumor nodules in the whole lung.

Ethics statement

The protocol for human research was approved by Fudan University Shanghai Cancer Center. Written informed consent was obtained from every patient who donated tissues. All work was performed in accordance with the approved protocol.

siRNA screen assay

Dharmacon siRNA reagent (#G-005805-01) was used. Reverse transfection method was used to deliver the siRNA to H23 cell67. Briefly, siRNA and lipid (Lipofectamine® 2000 Reagent) were mixed and added to 96-well plates. Then, H23 cells were added to the plates (10,000 cells per well). Cell proliferation rate was measured on day 3 by CCK8 assay. During screening, siRNAs targeting EGFP (5′-CGTGATCTTCACCGACAAGAT-3′) are included in the upper-most and lower-most rows of each plate, which served as negative control. The screening was conducted for one replica.

Cell culture and cell engineering

A549, NCI-H460, NCI-H226, NCI-H23, EKVX, Hop62 were purchased from ATCC as part of NCI-60 (American Typical Culture Collection, Manassas, VA, USA). Beas-2b, PC-9, HEK293T, and Phoenix cells were kindly provided by Dr. Kwok-Kin Wong (The Helen and Martin Kimmel Center for Stem Cell Biology, NYU). Human bronchial epithelial cells (HBEC) and human small airway epithelial cells (HSAEC) cell lines were kindly gifted by Dr. John Minna from the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center. Beas-2b, HEK293T, and Phoenix cells were cultured in DMEM plus 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). HBEC and HSAEC cells were cultured in SAGM medium (cc-3118, Lonza, Allendale, NJ, USA), and the rest of the NSCLC cell lines were cultured in RPMI-1640 with 10% FBS. To generate the Dox-inducible A549 (A549i) cell line, A549 cells were infected simultaneously with retrovirus encoding TetO-GATA4 (packaged from pREV-TRE-GATA4 vector) and retrovirus encoding EF1α-rtTA-iresGFP (packaged from pWPI-rtTA-iresGFP), then selected with 200 µg/mL Hygromycin (10687010, Invitrogen) for 2 weeks and FACS sorted for GFP-positive cells. For transient GATA4 expression, cell lines were infected with virus packaged from pWPI-GATA4 or control virus packaged from control construct pWPI-EGFP. For dox-induced knockdown of TGFβ2 or Wnt7b, pLKO-tet-puro vector harboring shRNA sequence targeting TGFβ2 or Wnt7b was packaged and infected A549 cells, then selected with 1 μg/mL puromycin (J593, Amresco) for 1 week. The lung cancer cell lines were authenticated by China Center for Type Culture Collection. All cell lines were maintained in mycoplasma-free environment by adding MYCO-3 (A5240,0020, AppliChem GmbH) and verified through PCR analysis (F: 5′-GGGAGCAAACAGGATTAGATACCCT-3′

R: 5′-TGCACCATCTGTCACTCTGTTAACCTC-3′).

To establish TGFβ2-expressing A549 stable cell line, HA-tagged TGFβ2-expressing DNA cassette CAG-TGFβ2-IRES-Neo was also electroporated (140 V, 25 ms) into A549 cell and selected with 700 µg/mL G418 (E859, Amresco) for 2 weeks. For shRNA knockdown, cells were infected with shRNA lentivirus (pLKO.1), selected with 2–3 µg/mL puromycin for 7–10 days. All cells were cultured in a 37 oC humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Plasmids

pCMV6-Entry-GATA4 (Myc-FLAG tagged) was purchased from Origene (RC210945, Rockville, MD, USA) and subcloned into lentivirial pWPI and retro-virial pREV-TRE vector, respectively. The pWPI plasmid was kindly gifted by Dr. Feng Shao at the National Institute of Biological Sciences (NIBS, Beijing, China). CAG-IRES-Neo plasmid was purchased from Addgene (deposited by Shinya Yamanaka, Addgene plasmid#13461) and the pREV-TRE retroviral plasmid (PT3215-5) and pTeton advanced plasmid (PT3899-5) were purchased from Clontech (Mountain View, CA, USA). Human TGFβ2 and CTNNB1 cDNA were purchased from NIBS Resource Center and then subcloned into CAG-IRES-Neo vector, respectively. Top-Flash plasmid was kindly gifted by Dr. Wei Wu in Tsinghua University. pSIN-DEST51-d2EGFP was kindly gifted by Dr. Yangming Wang in Peking University for construct microRNA sponge. All the following shRNAs were from the Biological Resource Center at NIBS, purchased from the Sigma Mission shRNA Library:

shGATA4#1(TRCN0000020424), shGATA4#2(TRCN0000329713),

shTGFB2(TRCN0000196326), shWnt7b(TRCN0000061877),

shTGFBR1(TRCN0000195626), shTGFBR2(TRCN0000040010),

shSMAD2(TRCN0000010477), shSMAD4(TRCN0000010323),

shBTBD11(TRCN0000136604), shDLX4(TRCN0000013776),

shEOMES (TRCN0000013175), shCDYL (TRCN0000276335),

shNkx2.5#1(TRCN0000013733), shNkx2.5#2(TRCN0000013734),

shSmarcd3#1(TRNC0000147806), shSmarcd3#2(TRCN0000179523),

shRelA#83 (TRCN0000014683), shRelA#86(TRCN0000014686),

shMMP7#1(TRCN0000304140), shMMP7#2(TRCN0000051843),

shCTNNB1#1(TRCN0000314991), shCTNNB1#2(TRCN0000314920),

shCDKN2B#1(TRCN0000038155), shCDKN2B#2(TRCN0000038156)

shCDKN2B#3(TRCN0000038157) and Luciferase shRNA (shLuc, SHC007) as a control shRNA.

siRNA screen assay

Dharmacon siRNA reagent (#G-005805-01) was delivered into H23 cell through Reverse transfection method67. Briefly, siRNA and lipid (Lipofectamine® 2000 Reagent, 11668019) were mixed and added to 96-well plates. Then, H23 cells were added to the plates (10,000 cells per well). Cell proliferation rate was measured on day 3 by CCK8 assay (CK04-20, Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc.). During screening, siRNAs targeting EGFP (5′- CGTGATCTTCACCGACAAGAT-3′) are included in the upper-most and lower-most rows of each plate, which served as negative control. The screening was conducted once.

Cell proliferation assay and Cell Titer-Glo assay

For cell proliferation assays, 50,000 A549i cells were seeded in each well of 12-well plates and cultured overnight. Dox was then added to a final concentration of 2 µg/mL. The cells were counted every other day.

For the Cell Titer-Glo assays, 5000 cells were seeded into each well of 96-well plates and cultured overnight, and the cells were cultured for another 48 h after adding Dox. Luminescence was measured using Cell Titer-Glo reagent (G5421, Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Doxycycline hyclate (D9891, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in ddH2O (2 mg/mL) and stored at −80 °C.

Soft-agar colony formation assay

Colony formation assays were performed in soft agar (0.6% lower gel and 0.35% upper gel) in six-well plates. A549 (10,000 cells), PC-9 (10,000 cells), H460 (10,000 cells), Beas-2b (10,000 Cells), NCI-H226 (10,000 cells), or NCI-H23 (10,000 cells) cells were seeded into each well of six-well plates. 2 µg/mL Dox was initially mixed with the upper gel, and 0.5 mL 1 × fluid media containing Dox was added to the surface of the upper gel every week. After 3–4 weeks, colonies were stained with 0.05% crystal violet. Colonies with the diameter over 200 µm were counted. The results are presented as mean values of triplicates.

Virus packaging and concentration

Lentiviral plasmids were co-transfected with helping plasmids, psPAX2 and PMD2.G (deposited by Didier Trono, Addgene plasmid #12260 and #12259) into HEK293T cells using transfection reagent VigoFect (Vigorous Biotechnology, Beijing, China). The cells were washed with fresh medium 6–8 h post transfection and cultured in fresh media. After 48 h of culture, virus containing supernatant was collected. To package retrovirus, viral plasmid and helping plasmid pCL-Eco (deposited by Inder Verma, Addgene plasmid#12371) were co-transfected into Phoenix cells, and virus-containing medium was collected as described above. All the retroviruses used in the mouse experiments were condensed by the following procedure: virus containing medium was centrifuged at 27,500 rpm for 2 h. The supernatant was carefully removed and the virus particles were resuspended with 100 μL Opti-medium. Shaking gently at 4 ℃ overnight, the virus was prepared for use.

RNA extraction and reverse-transcription PCR

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (15596-018, Invitrogen). 2 μg total RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using the Takara M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase Kit (D2639B, Takara, Dalian, China). Human GAPDH gene was used as an internal control. Real-Time PCR was done by using an ABI 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR machine (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies) and SYBR Premix Ex Taq II reagent (DRR820A, Takara). The following primers were used in the experiments:

TGFβ2-Forward: 5′-CTGTCTACCTGCAGCACACT-3′,

TGFβ2-Reverse: 5′- TGGGACTGTCTGGAGCACAA -3′,

Wnt7b-Forward: 5′- CGCAGCTATCAGAAGCCCAT-3′,

Wnt7b-Reverse: 5′- CAGGTGTTGCACTTGACGA-3′,

TGFBR1-Forward: 5′- CACAGAGTGGGAACAAAAAGGT-3′,

TGFBR1-Reverse: 5′- CCAATGGAACATCGTCGAGCA-3′,

TGFBR2-Forward: 5′- GTAGCTCTGATGAGTGCAATGAC-3′,

TGFBR2-Reverse: 5′- CAGATATGGCAACTCCCAGTG-3′,

SMAD4-Forward: 5′- ACGAACGAGTTGTATCACCTGG-3′,

SMAD4-Reverse: 5′- TGCACGATTACTTGGTGGATG-3′,

MMP7-Forward: 5′- ATGTGGAGTGCCAGATGTTGC-3′,

MMP7-Reverse: 5′- AGCAGTTCCCCATACAACTTTC-3′,

Gapdh-Forward:5′-GAAGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTC-3′,

Gapdh-Reverse:5′-GAAGATGGTGATGGGATTTC-3′

Protein extraction and immunoblotting

Whole cell lysates were extracted by using the lysis buffer: 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton, and 10% glycerol along with protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (4693132001& 4906837001, Roche, Basel, Switzerland) protein concentrations were determined by the Bradford assay. Soluble proteins (30–40 μg) were subjected to SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Separated proteins were electrophoretically transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and immunoblotted with anti-GATA4 (ab134057, 1:2000, Epitomics, Burlingame, CA, USA), -FLAG (F1804, 1:2000, Sigma), -CyclinD1 (2978S, 1:2000, CST, Danvers, MA, USA), -KRAS (12063-1-AP, 1:1000, Proteintech, Chicago, IL, USA), -Phos-ERK1/2 (4376S, 1:2000, CST), -Phos-AKT1 (3787S, 1:2000, CST), -ERK1/2 (4695S, 1:2000, CST), -AKT1 (2973S, 1:2000, CST), -PTEN (9188s, 1:1000 CST), -c-MYC (M4439, 1:2000, Sigma), -p21(2947S, 1:1000, CST), -p27(3686S, 1:1000, CST), -p53(2524S, 1:1000, CST), -p14/ARF(2407, 1:1000, CST), -p16/Ink4a (3562-1, 1:1000, Epitomics), -p15 (YT3492, 1:1000, ImmunoWay, Newark, DE, USA) or β-actin (A5316, 1:2000, Sigma) antibody. Immunoreactive proteins were visualized using ECL Western Blotting Substrate (PREGENE, Beijing, China) and X-ray films.

ARMS-PCR

Genomic DNAs were extracted from SH3166 and SH3a. ARMS-PCR was conducted on DNA samples with the primers listed below: G12A: ATA TAA ACT TGT GGT AGT TGG AGC TTC; G12C: AAT ATA AAC TTG TGG TAG TTG GAG CCT; G12D: ATA TAA ACT TGT GGT AGT TGG AGC GGA; G12R: AAT ATA AAC TTG TGG TAG TTG GAG CTC; G12S: AAT ATA AAC TTG TGG TAG TTG GAG CG A: G12V: ATA TAA ACT TGT GGT AGT TGG AGC AGT; Reverse: ATG CAC AGA GAG TGA ACA TCA TGG AC; WT: AAT ATA AAC TTG TGG TAG TTG GAG CTG.

Senescence associated β-Galactosidase (SA-β-Gal) staining

SA-β-Gal staining was performed using the Cell Signaling Senescence β-Galactosidase Staining Kit (CST #9860). Briefly, 20,0000–30,0000 cells were seeded in each well of six-well plates and cultured until the time of staining. For Dox treatment, a final concentration of 2 μg/mL was used and Dox containing medium was changed every other day. Wnt pathway inhibitors, ICG-001 (S2662), XAV939 (S2619), were purchased from Selleckchem (Houston, TX, USA) and were all dissolved in DMSO. Chemicals were added to the A549 cells (DMSO < 0.1%) for 4 days treatment and then underwent SA-β-Gal staining to see their effect in senescence.

For quantification of SA-β-Gal-positive cells elicited by GATA4 expression, blue positive cells in at least six randomly selected fields at ×200 magnification under an inverted microscope were counted. For shRNA knockdown cells, we calculated the percentage of SA-β-Gal cells in the three picked observed fields. The β-Gal staining for each group was experimentally repeated three times.

For SA-β-Gal staining of lungs tissues, krasG12D;GATA4-/- mice treated with inhibitors as indicated were fixed, washed with PBS/NP-40, and incubated in staining solution for β-galactosidase. Stained lungs were fixed 4% paraformaldehyde and embedded in paraffin. Section of 5 μm were stained with fast nuclear red. Senescence signaling was counted on cells stained blue.

Top-Flash assay

500 ng Top-Flash plasmid mixed with 200 ng CAG-CTNNB1-IRES-Neo plasmid and 500 ng pCMV6-GATA4 plasmid or 500 ng Empty Vector was transfected to A549 cell seeded in 12-well plate via VigoFect reagent. Both the treatment had three replicates. After 48 h culture, A549 cells were trypsinized and counted. 100 μL culture medium within 20,000 A549 cells was mixed with 100 μL Firefly Luciferase reagent (E1910, Promega, Madison, WI, USA) to measure the value of luminescence. For evaluation the effect of Wnt pathway inhibitors in Top-Flash assay, three inhibitors were added to the A549 cells post 24 h transfection for another 48 h incubation until the day of measurement.

microRNA assay

Total RNA of A549 cell was extracted by Trizol as described previously. 1 μg total RNA was reverse transcribed microRNAs via one step polyA-tailed assay in the following 25 μL mixture: 25 mM dNTP (2.5 μL), 100 mM ATP (2.5 μL), 2.5 mM MnCl2 (2.5 μL), 10 × E. coli PolyA Polymerase buffer (2.5 μL), QmiR-RT primer (5′- GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTTVN-3′,500 ng), RNase Inhibitor (0.5 μL), M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (1 μL) (Takara) and E. coli PolyA Polymerase (1 μL) (NEB, Ipswich, MA, USA). The reaction was run at 37 ℃ for 90 min and inactivated at 95 ℃ for 10 min. The following microRNAs primers were used in the Real-Time PCR and human U6 was an internal control.

qmiR-Reverse: 5′-GCGAGCACAGAATTAATACGAC-3′

hsa-miR-590-Forward: 5′-CGGCGGTAATTTTATGTATAAGCTAG-3′

hsa-miR-320c-1-Forward: 5′-GCGAAAAGCTGGGTTGAGAGGG-3′

hsa-miR-320a-Forward: 5′-TCGGAAAAGCTGGGTTGAGAGGGC-3′

hsa-miR-32-Forward: 5′-CGGCG TATTGCACATTACTAAGT-3′

hsa-miR-301b-Forward: 5′-CGGCGGCAGTGCAATGATATTGTC-3′

hsa-miR-29c-Forward: 5′-CGCCGTAGCACCATTTGAAATCGG-3′

hsa-miR-29b-1-Forward: 5′-CGGCGGTAGCACCATTTGAAATC-3′

hsa-miR-29a-Forward: 5′-TCGGTAGCACCATCTGAAATCGG-3′

hsa-miR-21-Forward: 5′-GCCGCTAGCTTATCAGACTGATG-3′

hsa-miR-199b-Forward: 5′-TCGGCCCAGTGTTTAGACTATCTG-3′

hsa-miR-193b-Forward: 5′-CGGGGTTTTGAGGGCGAGATGA-3′

hsa-miR-103b-2-Forward: 5′-TCATAGCCCTGTACAATGCTGC-3′

U6-Forward: 5′-CTCGCTTCGGCAGCACA-3′

U6-Reverse: 5′-AACGCTTCACGAATTTGCGT-3′

Four microRNA precursors were subcloned into the pLenti6 lenti-vrial vector (kindly gifted by Dr. Zhiqian Zhang at Beijing Cancer Hospital) and 10 μg/mL blasticidin (15205, Invitrogen) was used to select microRNA-expressing A549 cells. The following pre-sequences of four microRNAs were used in the experiment.

hsa-miR-590: 5′-TAGCCAGTCAGAAATGAGCTTATTCATAAAAGTGCAGTATGGTGAAGTCAATCTGTAATTTTATGTATAAGCTAGTCTCTGATTGAAACATGCAGCA-3′

hsa-miR-320a: 5′-GCTTCGCTCCCCTCCGCCTTCTCTTCCCGGTTCTTCCCGGAGTCGGGAAAAGCTGGGTTGAGAGGGCGAAAAAGGATAGGT-3′

hsa-miR-32: 5′-GGAGATATTGCACATTACTAAGTTGCATGTTGTCACGGCCTCAATGCAATTTAGTGTGTGTGATATTTTC-3′

hsa-miR-301b: 5′-GCCGCAGGTGCTCTGACGAGGTTGCACTACTGTGCTCTGAGAAGCAGTGCAATGATATTGTCAAAGCATCTGGGACCA-3′

To block mature microRNAs, miRNA sponges targeting hsa-miR-590, hsa-miR-320a, hsa-miR-32 and hsa-miR-301b was inserted into pSIN-DEST51-d2EGFP. The reverse and forward DNA (detailed below) was annealed:

miRNA-Sponge-F: TCGCCCTCTCGGTCAGCTTTTCCAGTGCAACTTAGCGCGTGCAATACCAGCTGCACTTTTCCCATAAGCTCCCAGGCTTTGACAAGAGATTGCACTGCCAGATCG

miRNA-Sponge-R: CTGGCAGTGCAATCTCTTGTCAAAGCCTGGGAGCTTATGGGAAAAGTGCAGCTGGTATTGCACGCGCTAAGTTGCACTGGAAAAGCTGACCGAGAGGGCGACGAT

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-Seq

ChIP was performed following lab protocol. Briefly, A549i cells were seeded in eight 150 mm plates, Dox was added to a final concentration of 2 µg/mL when the cells reached a confluence of 30–40%. After 4 days of culture, the cells were crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde (final concentration) and sonicated using the following parameters: 5 s on, 10 s off, 15 cycles at the 25% set power (VCX500, SONICS, CT, USA). The total cell lysate was divided into two aliquots, one was mixed with 40 μL of 1 mg/mL GATA4 antibody (6H10, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and 40 μL Protein A/G Agarose beads (20423, Pierce, Thermo Scientific), and the other was mixed with 40 μL 1 mg/mL normal mouse IgG (NI03, Sigma) and 40 μL Agarose beads. After overnight incubation, the beads were washed with ChIP washing buffer. Chromatin was eluted and the crosslink was reversed and DNA was extracted with phenol/chloroform. Finally, the eluted DNA was resolved in ddH2O and processed to NIBS Sequencing Center for further high through-put seq. The result can be downloaded at http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc = GSE85003

Mouse treatment

GATA4 gRNAs were designed, validated, and inserted in pSECC vector (generously provided by F.J. Sanchez-Rivera and T. Jacks, Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research at MIT). Lentivirus virus was packaged from pSECC-sgGATA4-infected 293T cells, validated through cell infection and administered nasally into lsl-KrasG12D mice. After tumor burden was confirmed by MRI imaging 12 weeks after virus infection, mice were treated with vehicle solution, SB525334 (S1476, Selleckchem) 10 mg/kg/day, Trametinib (a gift from Qingsong Liu at High Magnetic Field Laboratory, Chinese Academy of Sciences) 10 mg/kg/day and the combination of two drugs. Lung tumor was documented again 2 weeks after drug dosing. The ratio of tumor size to chest size was calculated to quantify tumor burden. The tumor burden is calculated by area of tumors per area of lung.

For PDX assay, SH3166 or SH3a PDX was embedded to nude mice. Mice were treated with TGFBR inhibitor (SB525334, 10 mg/kg/day), Cisplatin (S1166, Selleckchem) (5 mg/kg, once a week) or combination as the size of xenograft between 100 and 200 mm3. Two weeks after treatment, mice sacrificed. The tumor volume is calculated by the formula: volume = (width)2*length*0.5.

RNA-sequencing

We used four tumor/paratumoral tissue pairs of lung cancer patients: a 57-year-old female, a 60-year-old female, a 51-year-old male, and a 47-year-old male adenocarcinoma patient, respectively. Tumor and adjacent tissues were ground into powder in liquid nitrogen; total RNA was harvested using RNeasy Mini Kit (74104, QIAGEN); then total RNA samples were treated with DNase I and the mRNA is enriched by using the oligo(dT) magnetic beads.

RNA libraries were prepared for sequencing using standard Illumina protocols. Illumina Casava1.8 software used for base calling. Sequenced clean reads were mapped to Homo sapiens (hg19) whole genome using tophat v1.4.1 with parameters -i 10 -I 80000 --solexa1.3-quals --min-coverage-intron 20 --max-coverage-intron 11000 --min-segment-intron 10 --max-segment-intron 81000 --segment-length 20.

Gene annotation and calculation of FPKM values was carried out using Cufflinks (v2.0.2) with the provision of a GTF annotation file (hg19). Gene expression differences were assessed by Cuffdiff use upper-quartile normalization, with false discovery rate correction for multiple testing. The sequencing result can be downloaded at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE84852.

Statistic analysis

All the data were presented as mean values ± standard error of the mean. Differences between experimental groups were compared with unpaired two-tailed t-test. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 5.0, p < 0.05 was deemed to be statistically significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on experimental design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All the data referenced in the manuscript can be downloaded from websites indicated in the Methods section. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-Seq data for GATA4-binding sites in lung cancer can be downloaded from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE85003. RNA-seq data for tumor and paratumoral tissues data can be downloaded at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE84852.

References

Ferlay, J. et al. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer J. 136, E359–E386 (2015).

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J. Clin. 65, 5–29 (2015).

Herbst, R. S., Heymach, J. V. & Lippman, S. M. Lung cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 359, 1367–1380 (2008).

Li, T. et al. Tumor suppression in the absence of p53-mediated cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis, and senescence. Cell 149, 1269–1283 (2012).

Sherr, C. J. Principles of tumor suppression. Cell 116, 235–246 (2004).

Chen, Z. et al. A murine lung cancer co-clinical trial identifies genetic modifiers of therapeutic response. Nature 483, 613–617 (2012).

Sos, M. L. et al. PTEN loss contributes to erlotinib resistance in EGFR-mutant lung cancer by activation of Akt and EGFR. Cancer Res. 69, 3256–3261 (2009).

Whyte, W. A. et al. Master transcription factors and mediator establish super-enhancers at key cell identity genes. Cell 153, 307–319 (2013).

Winslow, M. M. et al. Suppression of lung adenocarcinoma progression by Nkx2-1. Nature 473, 101–104 (2011).

Snyder, E. L. et al. Nkx2-1 represses a latent gastric differentiation program in lung adenocarcinoma. Mol. Cell 50, 185–199 (2013).

Hsiao, J. J. & Fisher, D. E. The roles of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor and pigmentation in melanoma. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 563, 28–34 (2014).

Suva, M. L. et al. Reconstructing and reprogramming the tumor-propagating potential of glioblastoma stem-like cells. Cell 157, 580–594 (2014).

Liang, Q. R. et al. The transcription factor GATA4 is activated by extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1-and 2-mediated phosphorylation of serine 105 in cardiomyocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 7460–7469 (2001).

Merika, M. & Orkin, S. H. DNA-binding specificity of GATA family transcription factors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 13, 3999–4010 (1993).

He, A. B. et al. Dynamic GATA4 enhancers shape the chromatin landscape central to heart development and disease. Nat. Commun. 5, 4907 (2014).

Yu, W. et al. GATA4 regulates Fgf16 to promote heart repair after injury. Development 143, 936–949 (2016).

Liu, Q. et al. Genome-wide temporal profiling of transcriptome and open chromatin of early cardiomyocyte differentiation derived from hiPSCs and hESCs. Circ. Res. 121, 376 (2017).

Cirillo, L. A. et al. Opening of compacted chromatin by early developmental transcription factors HNF3 (FoxA) and GATA-4. Mol. Cell 9, 279–289 (2002).

Morimoto, T. et al. Phosphorylation of GATA-4 is involved in alpha(1)-adrenergic agonist-responsive transcription of the endothelin-1 gene in cardiac myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 13721–13726 (2000).

Yanazume, T. et al. Cardiac p300 is involved in myocyte growth with decompensated heart failure. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 3593–3606 (2003).

Takaya, T. et al. Identification of p300-targeted acetylated residues in GATA4 during hypertrophic responses in cardiac myocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 9828–9835 (2008).

He, A. B. et al. PRC2 directly methylates GATA4 and represses its transcriptional activity. Gene Dev. 26, 37–42 (2012).

Wang, J., Feng, X. H. & Schwartz, R. J. SUMO-1 modification activated GATA4-dependent cardiogenic gene activity. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 49091–49098 (2004).

Ackerman, K. G. et al. Gata4 is necessary for normal pulmonary lobar development. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 36, 391–397 (2007).

Guo, M. et al. Hypermethylation of the GATA genes in lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 7917–7924 (2004).

Azhikina, T., Kozlova, A., Skvortsov, T. & Sverdlov, E. Heterogeneity and degree of TIMP4, GATA4, SOX18, and EGFL7 gene promoter methylation in non-small cell lung cancer and surrounding tissues. Cancer Genet. 204, 492–500 (2011).

De Jong, W. K., Verpooten, G. F., Kramer, H., Louwagie, J. & Groen, H. J. Promoter methylation primarily occurs in tumor cells of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 29, 363–369 (2009).

Sanchez-Rivera, F. J. et al. Rapid modelling of cooperating genetic events in cancer through somatic genome editing. Nature 516, 428–431 (2014).

Gao, L. et al. Efficient generation of mice with consistent transgene expression by FEEST. Sci. Rep. 5, 16284 (2015).

Jackson, E. L. et al. Analysis of lung tumor initiation and progression using conditional expression of oncogenic K-ras. Genes Dev. 15, 3243–3248 (2001).

Zhou, W. et al. Novel mutant-selective EGFR kinase inhibitors against EGFR T790M. Nature 462, 1070–1074 (2009).

He, A., Kong, S. W., Ma, Q. & Pu, W. T. Co-occupancy by multiple cardiac transcription factors identifies transcriptional enhancers active in heart. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 108, 5632–5637 (2011).

Kang, C. et al. The DNA damage response induces inflammation and senescence by inhibiting autophagy of GATA4. Science 349, aaa5612 (2015).

Ye, X. et al. Downregulation of Wnt signaling is a trigger for formation of facultative heterochromatin and onset of cell senescence in primary human cells. Mol. Cell 27, 183–196 (2007).

Jeoung, J. Y. et al. A decline in Wnt3a signaling is necessary for mesenchymal stem cells to proceed to replicative senescence. Stem Cells Dev. 24, 973–982 (2015).

Thrasivoulou, C., Millar, M. & Ahmed, A. Activation of intracellular calcium by multiple Wnt ligands and translocation of beta-catenin into the nucleus: a convergent model of Wnt/Ca2+ and Wnt/beta-catenin pathways. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 35651–35659 (2013).

Huang, S. M. et al. Tankyrase inhibition stabilizes axin and antagonizes Wnt signalling. Nature 461, 614–620 (2009).

Emami, K. H. et al. A small molecule inhibitor of beta-catenin/CREB-binding protein transcription [corrected]. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 12682–12687 (2004).

Bertram, C. & Hass, R. MMP-7 is involved in the aging of primary human mammary epithelial cells (HMEC). Exp. Gerontol. 43, 209–217 (2008).

Bertram, C. & Hass, R. Matrix metalloproteinase-7 and the 20S proteasome contribute to cellular senescence. Sci. Signal. 1, pt1 (2008).

Romero, D., Iglesias, M., Vary, C. P. & Quintanilla, M. Functional blockade of Smad4 leads to a decrease in beta-catenin levels and signaling activity in human pancreatic carcinoma cells. Carcinogenesis 29, 1070–1076 (2008).

Gore, A. J., Deitz, S. L., Palam, L. R., Craven, K. E. & Korc, M. Pancreatic cancer-associated retinoblastoma 1 dysfunction enables TGF-beta to promote proliferation. J. Clin. Invest. 124, 338–352 (2014).

Clarke, D. C. & Liu, X. Decoding the quantitative nature of TGF-beta/Smad signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 18, 430–442 (2008).

Vijayachandra, K., Lee, J. & Glick, A. B. Smad3 regulates senescence and malignant conversion in a mouse multistage skin carcinogenesis model. Cancer Res. 63, 3447–3452 (2003).

Teng, Y. C. et al. Histone demethylase RBP2 promotes lung tumorigenesis and cancer metastasis. Cancer Res. 73, 4711–4721 (2013).

Calone, I. & Souchelnytskyi, S. Inhibition of TGFbeta signaling and its implications in anticancer treatments. Exp. Oncol. 34, 9–16 (2012).

Grygielko, E. T. et al. Inhibition of gene markers of fibrosis with a novel inhibitor of transforming growth factor-beta type I receptor kinase in puromycin-induced nephritis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 313, 943–951 (2005).

Ji, H. et al. Mutations in BRAF and KRAS converge on activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in lung cancer mouse models. Cancer Res. 67, 4933–4939 (2007).

Pikkarainen, S., Tokola, H., Kerkela, R. & Ruskoaho, H. GATA transcription factors in the developing and adult heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 63, 196–207 (2004).

Viger, R. S., Guittot, S. M., Anttonen, M., Wilson, D. B. & Heikinheimo, M. Role of the GATA family of transcription factors in endocrine development, function, and disease. Mol. Endocrinol. 22, 781–798 (2008).

Jay, P. Y. et al. Impaired mesenchymal cell function in Gata4 mutant mice leads to diaphragmatic hernias and primary lung defects. Dev. Biol. 301, 602–614 (2007).

Lee, F. T. et al. Enhanced efficacy of radioimmunotherapy with 90Y-CHX-A”-DTPA-hu3S193 by inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor AG1478. Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 7080s–7086s (2005).

Izumchenko, E. et al. The TGFbeta-miR200-MIG6 pathway orchestrates the EMT-associated kinase switch that induces resistance to EGFR inhibitors. Cancer Res. 74, 3995–4005 (2014).

Oh, S. A. et al. Foxp3-independent mechanism by which TGF-beta controls peripheral T cell tolerance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 114, E7536–E7544 (2017).

Lee, P. W., Severin, M. E. & Lovett-Racke, A. E. TGF-beta regulation of encephalitogenic and regulatory T cells in multiple sclerosis. Eur. J. Immunol. 47, 446–453 (2017).

Kanamori, M., Nakatsukasa, H., Okada, M., Lu, Q. & Yoshimura, A. Induced regulatory T cells: their development, stability, and applications. Trends Immunol. 37, 803–811 (2016).

Komai, T., Okamura, T., Yamamoto, K. & Fujio, K. The effects of TGF-betas on immune responses. Nihon Rinsho Men’eki Gakkai kaishi=Jpn. J. Clin. Immunol. 39, 51–58 (2016).

Eggert, T. et al. Distinct functions of senescence-associated immune responses in liver tumor surveillance and tumor progression. Cancer Cell 30, 533–547 (2016).

Guo, X. et al. Single tumor-initiating cells evade immune clearance by recruiting type II macrophages. Genes Dev. 31, 247–259 (2017).

Bendle, G. M., Linnemann, C., Bies, L., Song, J. Y. & Schumacher, T. N. Blockade of TGF-beta signaling greatly enhances the efficacy of TCR gene therapy of cancer. J. Immunol. 191, 3232–3239 (2013).

Tran, T. T. et al. Inhibiting TGF-beta signaling restores immune surveillance in the SMA-560 glioma model. Neuro Oncol. 9, 259–270 (2007).

Young, K. H., Gough, M. J. & Crittenden, M. Tumor immune remodeling by TGFbeta inhibition improves the efficacy of radiation therapy. Oncoimmunology 4, e955696 (2015).

Eser, P. O. & Janne, P. A. TGF beta pathway inhibition in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Pharmacol. Ther. 184, 112–130 (2018).

Azzi, S., Hebda, J. K. & Gavard, J. Vascular permeability and drug delivery in cancers. Front. Oncol. 3, 211 (2013).

Malviya, V. K., Young, J. D., Boike, G., Gove, N. & Deppe, G. Pharmacokinetics of mitomycin-C in plasma and tumor tissue of cervical cancer patients and in selected tissues of female rats. Gynecol. Oncol. 25, 160–170 (1986).

Huang, H. et al. YAP suppresses lung squamous cell carcinoma progression via deregulation of the DNp63-GPX2 axis and ROS accumulation. Cancer Res. 77, 5769–5781 (2017).

Erfle, H. et al. Reverse transfection on cell arrays for high content screening microscopy. Nat. Protoc. 2, 392–399 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Liang Hu for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank Drs. T. Jacks and K. Wong for providing the KrasG12D/+ and Tet-EGFR-T790M/Del19 mice. F.J. Sanchez-Rivera for providing the pSECC and LentiCRISPRv2 plasmids. This work was financially supported by National Key R&D Program of China (Grant 2016YFC0905500), Guangzhou Research Project of Science and Technology for Citizen Health (201803010124), NSFC (81672309, 81430066, 31621003, 91731314, 81872312), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (21618326), the National Basic Research Program of China (2017YFA0505500), the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDB19000000), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation Grant (2015M581673), and Chinese Academy of Science Taiwan Young Scholar Visiting Program (2015TW1SB0001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.G., Y.H., Y.T., Z.F., K.W., H.L., X.T., G. Zeng, S.Z., M.Z., Q.Z. and H.H. performed the experiments. X.H. did the patient gene expression and survival analysis. H.C. provided patient samples. G. Zhou provided Dharmacon siRNA reagent. G. Zhang and W.L. performed statistical analysis. Q.L. provided trametinib. L.Y. and Q.H. provided helpful comments. H.J. and L.C. conceived the work. H.J. and L.C. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gao, L., Hu, Y., Tian, Y. et al. Lung cancer deficient in the tumor suppressor GATA4 is sensitive to TGFBR1 inhibition. Nat Commun 10, 1665 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09295-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09295-7

This article is cited by

-

Metronomic and single high-dose paclitaxel treatments produce distinct heterogenous chemoresistant cancer cell populations

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

WNT ligands in non-small cell lung cancer: from pathogenesis to clinical practice

Discover Oncology (2023)

-

Comprehensive analysis of the immunological implication and prognostic value of CXCR4 in non-small cell lung cancer

Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy (2023)

-

In vivo genome-wide CRISPR screening identifies ZNF24 as a negative NF-κB modulator in lung cancer

Cell & Bioscience (2022)

-

A GATA4-regulated secretory program suppresses tumors through recruitment of cytotoxic CD8 T cells

Nature Communications (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.