Abstract

The discovery of more efficient, economical, and selective catalysts for oxidative dehydrogenation is of immense economic importance. However, the temperatures required for this reaction are typically high, often exceeding 400 °C. Herein, we report the discovery of subnanometer sized cobalt oxide clusters for oxidative dehydrogenation of cyclohexane that are active at lower temperatures than reported catalysts, while they can also eliminate the combustion channel. These results found for the two cluster sizes suggest other subnanometer size (CoO)x clusters will also be active at low temperatures. The high activity of the cobalt clusters can be understood on the basis of density functional studies that reveal highly active under-coordinated cobalt atoms in the clusters and show that the oxidized nature of the clusters substantially decreases the binding energy of the cyclohexene species which desorb from the cluster at low temperature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Exothermic oxidative dehydrogenation of alkanes is an attractive alternative to the energy demanding endothermic dehydrogenation route. However, despite decades of research efforts, the current oxidative dehydrogenation catalysts have limited activity and/or poor selectivity1. Supported small metal clusters have been shown to possess distinct catalytic properties not observed in their bulk analogs2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10. The special reactivity of the small clusters is believed to come from the unique electronic structure characteristics of the clusters11,12,13,14. For example, subnanometer Pt clusters have been identified as a highly active, as well as highly selective catalyst for the oxidative dehydrogenation of propane; the study provides a molecular level understanding of the catalyst8.

The oxidative dehydrogenation (ODH) of alkanes is exothermic overall and is, thus, a desirable substitute to dehydrogenation, which is an endothermic process requiring significant energy input. Current ODH processes are based on petroleum cracking that is indirect, environmentally unfriendly, and energy expensive due to the high temperatures required15,16. Thus, discovery of more efficient and direct catalysts for ODH is of immense economic importance. In addition, one must find catalysts that can perform partial dehydrogenation. For example, in the case of cyclohexane ODH as shown in Fig. 1, it is challenging to find catalysts that do not dehydrogenate products all the way to benzene.

Co-based catalysts have recently been getting lots of attention in dehydrogenation reactions, for e.g. few-atom Co(II) ions doped Zr-based MOFS NU-1000 was shown to be active around 230 °C for oxidative dehydrogenation of propane17,18; Co catalysts in other forms have also been used for oxidative dehydrogenation reactions, including highly dispersed CoOx in layered double oxides19, or cobalt-decorated graphene shells for both dehydrogenation and hydrogenation reactions20. Herein, we report results on subnanometer cobalt oxide clusters for the oxidative dehydrogenation of cyclohexane. The results show that under oxidative conditions oxidized subnanometer 4- and 27- atom cobalt clusters (Co4, Co27) are active at as low as 100 °C in cyclohexane oxidative dehydrogenation. In addition, product selectivity can be altered by changing the reaction conditions, in this case the oxygen to cyclohexane ratio.

This dramatic lowering of the temperature can be understood on the basis of density functional studies, which indicate that the oxidized nature of the Co clusters substantially decreases the binding energy of the alkene product, i.e. potential poisoning of the catalyst, in comparison with their metallic counterparts. The efficacy of sub-nanometer cobalt clusters for oxidative dehydrogenation at low temperatures is important since cobalt would be very attractive in a variety of industrially important oxidative processes that often utilize precious metals as catalysts and require high temperatures21,22,23. Such developments would have practical implications ranging from more energy efficient and environmentally friendly strategies for chemical synthesis to the replacement of current petrochemical feedstocks by inexpensive abundant small alkanes.

Results

Catalytic performance under atmospheric pressure

In this work, positively charged cobalt clusters were produced in a cluster beam (see Supplementary Figure 1 for a typical mass spectrum) and using a mass spectrometer, the Co4 or Co27 clusters were filtered out and deposited at 0.1 atomic monolayer coverage on a ~3 ML thick alumina film prepared by atomic layer deposition on the top of a doped Si chip. Applying the temperature ramp and experimental conditions shown in Fig. 2a, combined in situ grazing incidence small angle X-ray scattering (GISAXS), grazing incidence X-ray absorption near-edge structure (GIXANES) and temperature programmed reaction (TPRx) experiment under a total pressure of 800 mbar was used to monitor the sintering resistance, oxidation state and catalytic performance of the clusters.

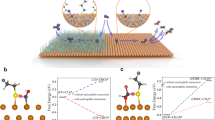

Performance of alumina-supported Co clusters under oxygen rich conditions (C6H12:O2 = 1:10). a Temperature ramp with gas environment applied. b r (rate of formation) for the major products cyclohexene (m/z = 67) on the Co4/Al2O3 catalyst (blue squares) and Co27/Al2O3 catalyst (blue circles), cyclohexadiene (m/z = 79) on the Co4/Al2O3 catalyst (red squares) and Co27/Al2O3 catalyst (red circles), and benzene (m/z = 78) on Co4/Al2O3 catalyst (black squares) and Co27/Al2O3 catalyst (black circles), and the byproduct CO2 (m/z = 44) on the Co4/Al2O3 catalyst (pink squares) and Co27/Al2O3 catalyst (pink circles). Cyclohexadiene mass is a superposition from 1,3- and 1,4- cyclohexadiene (both isomers have same electron ionization cross section53). c Carbon-based selectivity for the dominant reaction products with Co4/Al2O3 catalyst (blue: cyclohexene, red: cyclohexadiene, black: benzene, pink: CO2), and d Carbon-based selectivity for the dominant reaction products for Co27/Al2O3 catalyst (blue: cyclohexene, red: cyclohexadiene, black: benzene, pink: CO2). The interconnecting lines serve as guide to the eye

The experiments were performed using two different gas mixture compositions of cyclohexane (C6H12) and oxygen (O2) at 1:10 and 10:1 ratio of cyclohexane to oxygen ratio, both seeded in helium. Benzene, cyclohexene, cyclohexadiene, and CO2 were identified as the major products, along with trace amounts of cyclohexanone and cyclohexanol present. Under identical reaction conditions, the blank ALD alumina support showed no activity. Figure 2b shows the per total Co atom rate of formation (r) of the main products cyclohexene (C6H10), cyclohexadiene (C6H8), benzene (C6H6) and carbon dioxide (CO2) formed in the 1:10 C6H12/O2 mixture on the 4- and 27-atom cobalt clusters. The samples are active at 100 °C, with the Co4 clusters possessing a higher r than the Co27 clusters. r is calculated by the total number of product molecules formed per Co atom in the catalyst per second. As seen from the selectivity plots in Fig. 2c, d, the selectivities are very similar for the two cluster sizes, with combustion being the dominant and almost no benzene produced. The results indicate a highly efficient activation of molecular oxygen by the subnanometer Co clusters, demonstrated by the high amount of CO2 produced already at 100 °C. The reactivity results for the 10:1 C6H12/O2 mixture are shown in Fig. 3. r-values are tabulated in Supplementary Table 2. A comparison of performance of the subnanometer cobalt clusters with other reported cyclohexane ODH catalysts is listed in Supplementary Table 3, showing excellent performance of the subnanometer clusters. Measurable activity is again found at 100 °C, with the formation of CO2 apparently suppressed on both cluster sizes, with no CO2 observed on the Co4 clusters up to 200 °C. However, we need to note two important facts. First, there is an about order of magnitude difference observed in the total reaction rate for the two gas compositions; thus the lower conversion under oxygen lean conditions can shift selectivity towards the C6 products. Second, the first true measurement point is at 100 °C (no plateau in activity seen), thus a possible activity at lower temperatures is neglected. The activation energies estimated from the rates of product formation are 12.1 ± 0.9 kJ mol−1 (0.13 ± 0.01 eV), 24.4 ± 0.4 kJ mol−1 (0.25 ± 0.00 eV), and 32.0 ± 3.2 kJ mol−1 (0.33 ± 0.03 eV) for cyclohexene, cyclohexadiene, and benzene, respectively (as calculated from the Arrhenius plots shown in Supplementary Figures 9; ± denotes standard error). It is worth noting the very similar trends in activity and selectivity of Co4 and Co27. Another interesting feature, at comparable per atom activities, is the apparently worse linearity of the data in the Arrhenius plots for the larger clusters. We hypothesize, that it may reflect a higher fluxionality/structural dynamics of the larger clusters leading to more pronounced changes in their ensemble’s average structure and related activity evolving with temperature, than for the ensembles of smaller clusters, though size effects in cluster-support interactions may play a role as well24. The production of all C6 products was confirmed in the experiments performed in 1 mbar (L-edge XAS experiments; see Supplementary Table 1 in Supplementary Information), though a direct comparison of the obtained rates of formation cannot be made due to different reaction conditions.

Performance of alumina-supported Co clusters under oxygen lean conditions (C6H12:O2 = 10:1). a r (rate of formation) for the major products cyclohexene (m/z = 67) on the Co4/Al2O3 catalyst (blue squares) and Co27/Al2O3 catalyst (blue circles), cyclohexadiene (m/z = 79) on the Co4/Al2O3 catalyst (red squares) and Co27/Al2O3 catalyst (red circles), benzene (m/z = 78) on Co4/Al2O3 catalyst (black squares) and Co27/Al2O3 catalyst (black circles), and the byproduct CO2 (m/z = 44) on the Co4/Al2O3 catalyst (pink squares) and Co27/Al2O3 catalyst (pink circles). Cyclohexadiene mass is a superposition from 1,3- and 1,4- cyclohexadiene (both isomers have same electron ionization cross section53). b Carbon-based selectivity for the dominant reaction products with Co4/Al2O3 catalyst (blue: cyclohexene, red: cyclohexadiene, black: benzene, pink: CO2), and c Carbon-based selectivity for the dominant reaction products for Co27/Al2O3 catalyst (blue: cyclohexene, red: cyclohexadiene, black: benzene, pink: CO2). The interconnecting lines serve as guide to the eye

The main findings are the dramatically reduced temperature in comparison with previously reported ODH catalyst for propane and cyclohexane and the suppression of CO2 production for the lean conditions. The temperature of 100 °C, at which the ODH activity sets off, is lower than reported for propane ODH with Pt clusters (~400 °C)8 or in the ODH of cyclohexane by various catalysts, such as VOx (~400 °C)25, zeolites doped with transition metals (>300 °C)26, copper oxide-based (~250 °C)27, Au/Pd-based (200 °C)23, or FeOx, Au/Fe3O4 and Co3O4-based catalysts (~200–250 °C)28,29. In comparison with per exposed surface Co atom rates obtained for 6 nm Co3O4 particles29 tested under identical reaction conditions, the rate of formation of cyclohexene, cyclohexadiene, and benzene measured on the Co4 and Co27 clusters are higher by about a factor of 20, 100, and 1.2, respectively.

Cobalt oxidation state under atmospheric pressure

The GISAXS data showed no evidence of agglomeration of the clusters during the course of the reaction. The normalized in situ XANES Co-K edge spectra of the Co4 clusters obtained for oxygen rich and lean conditions are shown in Fig. 4 along with the XANES spectra of bulk Co standards. The features of the spectra of the clusters and their evolution with temperature are very similar under both gas mixtures. When compared with the spectra of the bulk standards Co, CoO, Co2O3, Co3O4, CoOOH, Co(OH)2, and CoAl2O4, the spectra of the clusters are indicative of Co(II). There is no evidence of Co(III) from the XANES spectra. The spectra of the as-prepared samples are broad and without distinct features, suggesting that Co clusters occupy various sites on the amorphous substrates, while structural, electronic, and charge effects in subnanometer clusters may be reflected in their spectra as well30. The lower intensity of the shoulder around 7719 eV typical of the tetrahedral coordination indicates a small fraction of Co ions at tetrahedral sites31,32. The XANES spectra of the cluster samples were analyzed by a linear combination fitting (LCF) using XANES spectra of bulk Co standards are shown in Supplementary Figure 2. (See Supplementary Figures 2b-c and 3b-c in the Supplementary Information showing the results from linear combination fit analysis for Co4 clusters.) The results of the analysis for the Co27 clusters are shown in Supplementary Figures 2d-e and 3d-e, respectively; examples of fitting results are presented in Supplementary Figures 4 and 5 of the Supplementary Information. The comparison of the spectra and the LCF results show similar trends for both cluster sizes under each reaction mixture and a somewhat higher hydroxide fraction for the 10:1 C6H12/O2 mixture. At room temperature, under He as well as under reactant gas mixture, the Co4 and Co27 clusters are present in the CoO phase. The features of the XANES spectra of both clusters Co4 and Co27 start to visibly evolve at 150 °C, and LCF analysis reveals the emergence of a Co(OH)2 phase that peaks at the highest temperatures applied (200–300 °C). Since, the fraction of the cobalt hydroxide component is higher under oxygen lean conditions when less water is produced, this hints towards the dehydrogenation of the cyclohexane molecule which causes the hydroxylation of cobalt, rather than the reaction with water formed during the ODH process. This hypothesis is confirmed by the observation that at room temperature, the fraction of the hydroxide is lower—both before and after the applied temperature ramp. The occurrence of a small fraction of CoAl2O4 at the highest temperatures most likely reflects the evolution of cluster-support interactions during the course of the reaction, possibly accompanied with structural changes in the clusters. Overall, the Co atoms within the clusters retain their oxidation state of 2+ during the entire test. We hypothesize that the reluctance of subnanometer Co clusters to change their 2+ oxidation state may be responsible for their excellent performance as ODH catalysts working at surprisingly low temperatures, through the nanoeffect. This hypothesis is supported by reports on the strongly size-dependent redox behavior of cobalt oxide particles. It was shown, that, for example, wurztite type CoO nanoparticles resist to reduction and oxidation, in contrary to larger oxide particles or macroscopic Co samples33. Other studies demonstrated the stable 2+ state of cobalt in subnanometer cobalt oxide clusters when exposed to elevated temperatures34 or under cyclohexene ODH conditions35,36. Interrogations of oxidized size-selected cobalt nanoparticles, under similar cyclohexane ODH conditions as applied in the present study, determined ~3 nm as the critical size for cobalt oxide particles37: Particles larger than 3 nm underwent size-dependent changes in their morphology as well as in the oxidation state of cobalt. In contrary, the smaller particles were robust and retained oxidation state 2+. Such tunability of the oxidation state through variable particle size may offer high-fidelity control knob over the performance of catalysts in general.

In situ XANES spectra of Co4 clusters collected during the applied ramp. a spectra acquired under cyclohexane oxygen 1:10 ratio and b under and 10:1 ratio seeded in He; spectra collected at the indicated temperatures applied from the start (bottom) of the temperature ramp to its end (top). He denotes spectra collected under helium. c XANES spectra of bulk Co standards: Co foil (pink line), CoO (dark green line), Co(OH)2 (dark blue line), Co2O3 (light green line), Co3O4 (red line), CoAl2O3 (cyan line) and CoOOH (black line). (Spectrum of CoOOH adapted with permission from ref. 54, CopyRight (2018) of the American Chemical Society

Cobalt oxidation state under low pressure

Additional characterization was performed at the Co-L edge under ultra-high vacuum (UHV) and in situ conditions in 1 mbar pressure (see Supplementary Figure 6 in the Supplementary Information). The XAS characterization reveals that the clusters, independent of their size (4 vs. 27) behave very similar in Co L-edge under oxidative conditions and that both Co4 and Co27 can be best described as CoO (in a good agreement with XANES) with the Co2+ cation in tetrahedral coordination. Since the spectra of Co4 and Co27 under the same experimental conditions are practically identical, in what follows we will discuss the Co4 case. Spectra in vacuum and under reaction condition display small but clearly discernable differences. In order to extract this information from the L-edge absorption spectra, the experimental UHV and ODH XAS spectra were simulated using the charge-transfer multiplet (CTM) approach38,39,40,41, (see Supplementary Figure 7 in Supplementary Information). The tetrahedral symmetry is chosen for the calculations, with the crystal field value 10Dq = −0.3 eV. The optical parameter Dt changes from −0.22 eV to −0.20 eV when simulating the UHV and the ODH spectrum, respectively. This subtle change in the Dt value indicates a slight change in the energy position of the d-orbitals38. The charge-transfer energy value (Δ) changes from 9 eV to 7 eV between the two states (UHV and ODH). A decrease in the Δ value corresponds to a decrease in the 3d8 to 3d9L ratio in the ground state, i.e. the 3d-state of Co interacts more with the delocalized electron from the oxygen 2p valence band. Therefore, this decrease in the Δ values implies that the covalent bonding between oxygen and cobalt becomes stronger during reaction.

Insights into low-temperature activity

To understand the observed low-temperature activity of small Co clusters for cyclohexane oxidative dehydrogenation, we carried out DFT calculations on key steps for the reaction pathway involving the Co4 cluster. The DFT calculations were carried out for Co4O4 clusters based on the XANES results above showing that the Co is in a 2+ state. They were supported on a θ-alumina surface. The Co4O4 clusters should also be representative for the Co27 cluster. This can be justified by the similarities of the X-ray spectra of Co4 and Co27 showing a dominant CoO type composition, as well as the similar catalytic performance of the two clusters. The location of the cluster was optimized on the surface. As shown in the XANES studies the cluster remains oxidized throughout the experiment. Thus we assume that O2 cleavage is not a crucial step. The θ–alumina surface was chosen and is an approximation to the amorphous alumina surface created by ALD used in the experimental studies.

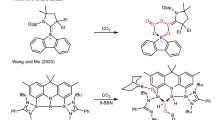

Within the temperature range studied, reaction pathway A (Fig. 1) appears as the predominant channel since cyclohexene is the major C6 species produced, moreover at the lowest temperature. The calculated transition states and intermediates for pathway A presented in Fig. 1, leading to formation of cyclohexene on the Co4O4 cluster are shown in Fig. 5. There is no apparent barrier (referenced to gas phase cyclohexane) for breaking of the first C–H bond and the true barrier for this step is 0.47 eV. The true barrier for breaking the second C–H bond is much smaller at 0.15 eV. The pathway is thermodynamically downhill by 0.41 eV to form cyclohexene, which binds to Co4O4 by its π-bond. The reason that the second barrier is lower than the first is that the presence of cyclohexyl group bound to cobalt weakens the Co–O bond and makes the site more active. The reason that the first and second C–H bond breaking barriers are low is the presence of hydrogen on the cluster that weakens the Co–O bond (makes it a dative bond as opposed to a covalent bond without hydrogen) destabilizing the cluster and making the Co–O site more active. Thus, the C–H bond interacts across the active Co–O decreasing the C–H activation energy. The hydrogen transfer to the alumina surface regenerates the Co–O active site for the breaking of the second C–H bond. The apparent barrier for the reaction is 0.20 eV corresponding to the hydrogen transfer. The hydrogens in this mechanism are assumed to initially come from the hydroxylated amorphous alumina surface via hydrogen transfer and subsequently from the ODH reaction. The subsequent steps involve the desorption of cyclohexene from the Co4 cluster and the regeneration of the catalyst by removal of the hydrogens through the oxygens. The pathway is completed by the regeneration of the catalyst by the removal of the hydrogen through hydroxyl groups on the surface. Thus, in the overall reaction scheme, surface hydroxyl groups serve as the means for removal of hydrogen from the catalyst as water. We also note that all atoms in the cluster play a role in the reaction pathway and that the reaction is not occurring at a single atom of the cluster.

Discussion

The activation energy barrier determined from the experimental data for the Co4O4/Al2O3 catalyst for cyclohexene formation is 0.15 eV (as calculated from the Arrhenius plot shown in Supplementary Figure 9) and is a good agreement with the calculated value from DFT barrier of 0.20 eV shown in Fig. 5. The activation energy with Co clusters is substantially lower than the previously reported catalysts29,42,43. Theory leads to the conclusion that under-coordinated Co sites in small ConOm clusters are highly active for cyclohexane ODH. This can be explained by the attractive interaction between the under-coordinated Co and cyclohexane. The DFT calculations show that the initial adsorption complex between cyclohexane and the Co4O4 cluster (Fig. 5) results in significant charge transfer from a cyclohexane C–H bonding orbital to the cluster, as also shown in XAS simulations of the experimental spectra. The binding energy of cyclohexene to the cluster (0.6 eV, obtained relative to starting products) is especially notable since it is much lower than that of propene in the case of Pt clusters8. The weaker binding of cyclohexene could explain the lower temperature required for cyclohexane ODH compared to propane ODH on Pt clusters. The smaller binding energy is due to the oxidized nature of the Co clusters.

The work here reports on selective low temperature oxidative dehydrogenation of cyclohexane driven by subnanometer size oxidized cobalt clusters, with cyclohexene as the dominant product. Density functional studies explain that the high activity towards cyclohexene at low temperatures originates from the combination of the intrinsic reactivity of the small clusters combined with the small binding energy of cyclohexene on the oxidized clusters. This joint computational and experimental study indicate that cobalt-based clusters may hold a great promise for a new class of low-temperature oxidation catalysts for a broad spectrum of oxidative processes.

Methods

ALD alumina film preparation

The support, a ~3 ML thin alumina film was created by atomic layer deposition (ALD) on the top of a naturally oxidized n-type (phosphorus doped) Si chip. This ALD alumina support was proved to strongly bind subnanometer cobalt clusters with a binding energy of 3.2–4.6 eV34 and keep the clusters from sintering at elevated temperatures30.

Deposition of size-selected clusters

The production of Co clusters was done using a well-established size-selective method in the gas phase, followed by soft-landing the clusters of desired size on the support8,12. Within this synthesis approach, the beam of positively charged Co clusters was produced in a vacuum apparatus in a laser vaporization cluster source utilizing the 532 nm wavelength radiation of a frequency doubled Nd:YAG laser focused on a rotating cobalt target rod. Helium was used as carrier gas, and the positively charged clusters led through an ion guide assembly made of an electrostatic lense assembly into a quadrupole mass filter. (Supplementary Figure 1 shows typical mass spectra of positively charged cobalt clusters with the throughput of the cluster apparatus tuned for smaller or larger cobalt clusters.) Next, the Co4 or Co27 clusters of interest were selected out of the beam on the quadrupole mass filter and deflected towards the support using an electrostatic quadrupole deflector. Finally, the Co4 or Co27 clusters were deposited with a kinetic energy of less than 1 eV/atom on the alumina support. In order to preserve the size specificity of the clusters on the support upon landing, the applied surface coverage was limited to 0.1 of an atomic monolayer equivalent (ML). The amount of deposited metal and the level of surface coverage were determined by real-time monitoring of the flux of clusters landing on the support and the diameter of the area covered by clusters. At the given surface coverage, the average inter-cluster distance is estimated to be within ~2–4 nm, as also verified by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) collected on other cluster samples with similar surface coverage44. After deposition, the cluster samples are exposed to air, which may cause the oxidation of cobalt.

Combined in situ GISAXS, GIXANES, and TPRx

experiments under a pressure of 800 mbar was used to monitor the sintering resistance, oxidation state, and catalytic performance at the advanced photon source facility (APS, Sector 12-ID-C) of Argonne National Laboratory. The reactant mixture comprised of cyclohexane (0.4%) in helium which was pre-mixed with oxygen to attain a 1:10 (or 10:1) cyclohexane to oxygen ratio and was fed into the reactor at a flow of 30 sccm29. Details of the GISAXS/GIXANES/TPRx approach are given for example in ref. 45. The reaction products were analyzed using a differentially pumped mass-spectrometer (Pfeiffer Vacuum Prisma QMS 200) continuously sampling from the reaction cell. Typical raw reactivity data are shown in Supplementary Figure 10. The rates of formation of products were calculated using the number of deposited Co atoms and calibrating the mass spectrometer using diluted calibrated gas mixtures (AirGas). The GIXANES data were analyzed with IFEFFIT interactive software package (with ATHENA and ARTEMIS graphical interfaces)46. The GISAXS data were collected on a Platinum detector developed by the Advanced Photon Source (1024 × 1024 pixels) with X-rays of 7.6 keV as a function of temperature. The two-dimensional GISAXS images were then cut both in horizontal and vertical directions. The scattering is then compared with background on the alumina thin film.

In situ XAS characterization

Additional characterization was performed at the BESSY II photon source (Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin) using in situ TEY (total electron yield) X-ray absorption (XAS) on the Co L-edge under 1 mbar pressure, combined with product analysis using a microGC (Varian). Details about the experimental setup can be found for example in ref. 47. The XAS experiments were performed on identical Co4 and Co27 samples as those used at the APS, under ultra-high vacuum (UHV) and in situ conditions under 1 mbar pressure with 12 sccm gas flow of a gas mixture containing 96% He, 2% cyclohexane, and 2% oxygen.

Simulations of the XAS spectra

The experimental XAS spectra were simulated using the charge-transfer multiplet (CTM) approach38,39,40,41. The calculations have been carried out using the CTM4XAS vs3.1 program48. The difference between the core hole potential and the 3d–3d repulsion energy as well as the hopping parameters were taken from literature data40,41. Only the L3 edge is presented in the experimental results, since the L3 to L2 ratio is practically the same in the experimental and simulated curves. The core hole potential Q is taken 2.0 eV higher than the 3d–3d repulsion energy Udd. The value for the hopping eg electrons (te) is 1.0 eV, while for the hopping t2g electrons (tt) is 2.0 eV.

Density functional theory

All calculations used periodic DFT as implemented in the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package 5.2 (VASP)49,50. The ion–electron interactions were described using the projector augmented wave (PAW) potentials with an energy cutoff of 400 eV for the plane wave basis set. The generalized gradient corrected Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (GGA-PBE) functional was used for all periodic calculations with Monkhorst-Pack 5 × 5 × 1 k-point sampling51,52. Optimizations were carried out until the forces converged to 0.02 eV/Å for geometry optimizations and 0.05 eV/Å for nudged elastic band calculations using the quasi-Newton method for geometry optimization. The Co4O4 cluster was supported on a θ-Al2O3 surface which was modeled in a slab geometry with a (2 × 2) lateral periodicity. Six repeated Al2O3 layers were used to describe the surface, of which the three top layers were allowed to relax. The location and structure of the Co4O4 cluster was optimized on the surface see Supplementary Figure 8). The slabs are separated by a vacuum distance of 16 Å. The cluster has a magnetic moment and therefore spin- polarization was considered in all calculations. Zero-point energies are not included.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

References

Cavani, F., Ballarini, N. & Cericola, A. Oxidative dehydrogenation of ethane and propane: how far from commercial implementation? Catal. Today 127, 113–131 (2007).

Ma, X.-L., Liu, J.-C., Xiao, H. & Li, J. Surface single-cluster catalyst for N2-to-NH3 thermal conversion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 46–49 (2018).

Liu, J.-C. et al. Heterogeneous Fe3 single-cluster catalyst for ammonia synthesis via an associative mechanism. Nat. Commun. 9, 1610 (2018).

Qiao, B. et al. Single-atom catalysis of CO oxidation using Pt1/FeOx. Nat. Chem. 3, 634–641 (2011).

Liu, L. et al. Generation of subnanometric platinum with high stability during transformation of a 2D zeolite into 3D. Nat. Mater. 16, 132–138 (2017).

Nesselberger, M. et al. The effect of particle proximity on the oxygen reduction rate of size-selected platinum clusters. Nat. Mater. 12, 919–924 (2013).

Lei, Y. et al. Increased silver activity for direct propylene epoxidation via subnanometer size effects. Science 328, 224–228 (2010).

Vajda, S. et al. Subnanometre platinum clusters as highly active and selective catalysts for the oxidative dehydrogenation of propane. Nat. Mater. 8, 213–216 (2009).

Yoon, B. et al. Charging effects on bonding and catalyzed oxidation of CO on Au8 clusters on MgO. Science 307, 403–407 (2005).

Kaden, W. E., Wu, T., Kunkel, W. A. & Anderson, S. L. Electronic structure controls reactivity of size-selected Pd clusters adsorbed on TiO2 surfaces. Science 326, 826–829 (2009).

Tyo, E. C. & Vajda, S. Catalysis by clusters with precise numbers of atoms. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 577–588 (2015).

Vajda, S. & White, M. G. Catalysis applications of size-selected cluster deposition. ACS Catal. 5, 7152–7176 (2015).

Luo, Z., Castleman, A. W. & Khanna, S. N. Reactivity of metal clusters. Chem. Rev. 116, 14456–14492 (2016).

Halder, A., Curtiss, L. A., Fortunelli, A. & Vajda, S. Perspective: size selected clusters for catalysis and electrochemistry. J. Chem. Phys. 148, 110901 (2018).

Bond, G. C. in In Metal-Catalyzed Reactions of Hydrocarbons (eds Spencer, M. S. & Twigg, M. V.) (Springer, Heidelberg, 2005).

Olah, G. A. Hydrocarbon Chemistry. (Wiley-Interscience, New York, 1995).

Li, Z. et al. Fine-tuning the activity of metal–organic framework-supported cobalt catalysts for the oxidative dehydrogenation of propane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 15251–15258 (2017).

Li, Z. et al. Metal–organic framework supported cobalt catalysts for the oxidative dehydrogenation of propane at low temperature. ACS Cent. Sci. 3, 31–38 (2017).

Huang, M.-X. et al. Highly dispersed CoOx in layered double oxides for oxidative dehydrogenation of propane: guest–host interactions. RSC Adv. 7, 14846–14856 (2017).

Li, J. et al. Different active sites in a bifunctional Co@N-doped graphene shells based catalyst for the oxidative dehydrogenation and hydrogenation reactions. J. Catal. 355, 53–62 (2017).

Wang, Y., Shah, N. & Huffman, G. P. Pure hydrogen production by partial dehydrogenation of cyclohexane and methylcyclohexane over nanotube-supported Pt and Pd catalysts. Energy Fuels 18, 1429–1433 (2004).

Guan, Y. & Hensen, E. J. M. Ethanol dehydrogenation by gold catalysts: the effect of the gold particle size and the presence of oxygen. Appl. Catal. A. 361, 49–56 (2009).

Dummer, N. F., Bawaked, S., Hayward, J., Jenkins, R. & Hutchings, G. J. Reprint of: oxidative dehydrogenation of cyclohexane and cyclohexene over supported gold, –palladium catalysts. Catal. Today 160, 50–54 (2011).

Ha, M.-A., Baxter, E. T., Cass, A. C., Anderson, S. L. & Alexandrova, A. N. Boron switch for selectivity of catalytic dehydrogenation on size-selected Pt clusters on Al2O3. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 11568–11575 (2017).

Feng, H., Elam, J. W., Libera, J. A., Pellin, M. J. & Stair, P. C. Catalytic nanoliths. Chem. Eng. Sci. 64, 560–567 (2009).

Aliev, A. M., Shabanova, Z. A., Nadzhaf-Kuliev, U. M. & Medzhidova, S. M. Oxidative dehydrogenation of cyclohexane over modified zeolite catalysts. Pet. Chem. 56, 639–645 (2016).

Nauert, S. L., Schax, F., Limberg, C. & Notestein, J. M. Cyclohexane oxidative dehydrogenation over copper oxide catalysts. J. Catal. 341, 180–190 (2016).

Goergen, S. et al. Structure sensitivity of oxidative dehydrogenation of cyclohexane over FeOx and Au/Fe3O4 nanocrystals. ACS Catal. 3, 529–539 (2013).

Tyo, E. C. et al. Oxidative dehydrogenation of cyclohexane on cobalt oxide (Co3O4) nanoparticles: the effect of particle size on activity and selectivity. ACS Catal. 2, 2409–2423 (2012).

Yin, C. et al. Size- and support-dependent evolution of the oxidation state and structure by oxidation of subnanometer cobalt clusters. J. Phys. Chem. A 118, 8477–8484 (2014).

Ciuparu, D. et al. Mechanism of cobalt cluster size control in Co-MCM-41 during single-wall carbon nanotubes synthesis by CO disproportionation. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 15565–15571 (2004).

Della Longa, S. et al. An X-ray absorption near edge structure spectroscopy study of metal coordination in Co(II)-substituted Carcinus maenas hemocyanin. Biophys. J. 65, 2680–2691 (1993).

Papaefthimiou, V. et al. Nontrivial redox behavior of nanosized cobalt: new insights from ambient pressure X-ray photoelectron and absorption spectroscopies. ACS Nano 5, 2182–2190 (2011).

Ferguson, G. A. et al. Stable subnanometer cobalt oxide clusters on ultrananocrystalline diamond and alumina supports: oxidation state and the origin of sintering resistance. J. Phys. Chem. C 116, 24027–24034 (2012).

Lee, S. et al. Oxidative dehydrogenation of cyclohexene on size selected subnanometer cobalt clusters: improved catalytic performance via evolution of cluster-assembled nanostructures. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 14, 9336–9342 (2012).

Lee, S. et al. Support-dependent performance of size-selected subnanometer cobalt cluster-based catalysts in the dehydrogenation of cyclohexene. ChemCatChem 4, 1632–1637 (2012).

Bartling, S. et al. Pronounced size dependence in structure and morphology of gas-phase produced, partially oxidized cobalt nanoparticles under catalytic reaction conditions. ACS Nano 9, 5984–5998 (2015).

De Groot, F. High-resolution X-ray emission and X-ray absorption spectroscopy. Chem. Rev. 101, 1779–1808 (2001).

Ikeno, H., de Groot, F. M., Stavitski, E. & Tanaka, I. Multiplet calculations of L2, 3 x-ray absorption near-edge structures for 3d transition-metal compounds. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 21, 104208 (2009).

Morales, F. et al. In situ X-ray absorption of Co/Mn/TiO2 catalysts for Fischer-Tropsch synthesis. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 16201–16207 (2004).

Papaefthimiou, V. et al. When a metastable oxide stabilizes at the nanoscale: wurtzite CoO formation upon dealloying of PtCo nanoparticles. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2, 900–904 (2011).

Ali, L. I., Ali, A.-G. A., Aboul-Fotouh, S. M. & Aboul-Gheit, A. K. Dehydrogenation of cyclohexane on catalysts containing noble metals and their combinations with platinum on alumina support. Appl. Catal. A 177, 99–110 (1999).

Koel, B. E., Blank, D. A. & Carter, E. A. Thermochemistry of the selective dehydrogenation of cyclohexane to benzene on Pt surfaces. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 131, 39–53 (1998).

Lu, J. et al. Effect of the size-selective silver clusters on lithium peroxide morphology in lithium-oxygen batteries. Nat. Commun. 5, 4895 (2014).

Lee, S., Lee, B., Seifert, S., Vajda, S. & Winans, R. E. Simultaneous measurement of X-ray small angle scattering, absorption and reactivity: a continuous flow catalysis reactor. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 649, 200–203 (2011).

Ravel, B. & Newville, M. ATHENA, ARTEMIS, HEPHAESTUS: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 12, 537–541 (2005).

Knop‐Gericke, A. et al. Chapter 4 X‐Ray photoelectron spectroscopy for investigation of heterogeneous catalytic processes. Adv. Catal. 52, 213–272 (2009).

Stavitski, E. & De Groot, F. M. The CTM4XAS program for EELS and XAS spectral shape analysis of transition metal L edges. Micron 41, 687–694 (2010).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Perdew, J. P. et al. Atoms, molecules, solids, and surfaces: applications of the generalized gradient approximation for exchange and correlation. Phys. Rev. B 46, 6671–6687 (1992).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Jiao, C. Q. & Adams, S. F. Electron ionization of 1,3-cyclohexadiene and 1,4-cyclohexadiene. Int. J. Mass. Spectrom. 376, 35–38 (2015).

Thenuwara, A. C. et al. Cobalt intercalated layered NiFe double hydroxides for the oxygen evolution reaction. J. Phys. Chem. B 122, 847–854 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Drs. Jeffrey W. Elam and Joseph A. Libera for providing the ALD—coated substrates. The work at Argonne was supported by the US Department of Energy, BES Materials Sciences under Contract DEAC02–06CH11357 with UChicago Argonne, LLC, operator of Argonne National Laboratory. The work at the Advance Photon Source (beamline 12-ID-C) was supported by the US Department of Energy, Scientific User Facilities under Contract DEAC02–06CH11357 with UChicago Argonne, LLC, operator of Argonne National Laboratory. A.H. thanks for the support provided by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research. We thank Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin for allocation of synchrotron radiation beamtime.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.L. contributed to sample synthesis, in situ GISAXS/GIXANES/TPRx experiments data analysis and writing of the paper, A.H. contributed to GISAXS/GIXANES/TPRx data analysis and writing of the paper, G.A.F. contributed to theoretical calculations and writing of the paper, S.S. contributed to in situ GISAXS/GIXANES/TPRx experiments and data analysis, R.E.W. contributed to in situ GISAXS/GIXANES/TPRx experiments, D.T. and R.S. contributed to NEXAFS/reactivity experiments, V.P. contributed to the modeling and interpretation of NEXAFS spectra, J.G contributed to theoretical calculations and writing of the paper, L.A.C. contributed to theoretical calculations and writing of the paper, S.V. contributed to in situ GISAXS/GIXANES/TPRx experiments, data interpretation and writing of the paper; he also coordinated the studies.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, S., Halder, A., Ferguson, G.A. et al. Subnanometer cobalt oxide clusters as selective low temperature oxidative dehydrogenation catalysts. Nat Commun 10, 954 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08819-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08819-5

This article is cited by

-

On the nature of Con±/0 clusters reacting with water and oxygen

Communications Chemistry (2024)

-

The selective deposition of Fe species inside ZSM-5 for the oxidation of cyclohexane to cyclohexanone

Science China Chemistry (2021)

-

Synthetic strategies of supported atomic clusters for heterogeneous catalysis

Nature Communications (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.