Abstract

The transition temperature Tc of unconventional superconductivity is often tunable. For a monolayer of FeSe, for example, the sweet spot is uniquely bound to titanium-oxide substrates. By contrast for La2−xSrxCuO4 thin films, such substrates are sub-optimal and the highest Tc is instead obtained using LaSrAlO4. An outstanding challenge is thus to understand the optimal conditions for superconductivity in thin films: which microscopic parameters drive the change in Tc and how can we tune them? Here we demonstrate, by a combination of x-ray absorption and resonant inelastic x-ray scattering spectroscopy, how the Coulomb and magnetic-exchange interaction of La2CuO4 thin films can be enhanced by compressive strain. Our experiments and theoretical calculations establish that the substrate producing the largest Tc under doping also generates the largest nearest neighbour hopping integral, Coulomb and magnetic-exchange interaction. We hence suggest optimising the parent Mott state as a strategy for enhancing the superconducting transition temperature in cuprates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Exposed to pressure, the lattice parameters of a material generally shrink. In turn, the electronic nearest neighbour hopping integral t increases, due to larger orbital overlap. In a Mott insulator this enhancement can trigger a bandwidth-controlled insulator-to-metal transition1. Indeed, the ratio, U/t, of the electron-electron (Coulomb) interaction U and the hopping t may be driven below its critical value. This premise has led to prediction of a pressure-induced insulator-to-metal transition in hypothetical solid hydrogen2. Experimentally, pressure-induced metallisations have been realised, e.g., in NiS23 and organic salts4. However, besides its impact on the bandwidth, pressure also influences (in a complex fashion) the electron-electron interaction U—an effect that has received little attention so far. The fate of Mott insulators exposed to external pressure therefore remains an interesting (and unresolved) problem to consider.

In the case of layered copper-oxide materials (cuprates), superconductivity emerges once the Mott insulating state is doped away from half-filling5. In fact, it is commonly believed that the Mott state is a precondition for cuprate high-temperature superconductivity. While the optimal doping has been established for all known cuprate systems, the ideal configuration—for superconductivity—of the parent Mott state has not been identified. Typically, it is reported that hydrostatic pressure has a positive effect on Tc6,7. However, the microscopic origin of this finding remains elusive. In particular, how pressure influences the local Coulomb interaction U and the inter-site magnetic-exchange interaction—to lowest order—Jeff = 4t2/U, is an unresolved problem.

Here we present a combined x-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) and resonant inelastic x-ray scattering (RIXS) study of the La2CuO4 Mott insulating phase. We show that by straining thin films, the crystal field environment, as well as the energy scales t and U that define the degree of electronic correlations, can be tuned. In stark contrast to predictions for elementary hydrogen2 and observations on standard Mott insulating compounds3,4, we demonstrate that U/t remains approximately constant with in-plane strain. In La2CuO4, both U and t are increasing with compressive strain. In-plane strain is therefore not pushing La2CuO4 closer to the metallisation limit. Instead, strain enhances the stiffness, i.e., the exchange interaction Jeff, of the antiferromagnetic ordering. These experimental observations are consistent with our band structure and constrained Random Phase Approximation (cRPA) calculations that reveal the same trends for t, U and Jeff. For superconductivity, originating from the anti-ferromagnetic pairing channel, the exchange interaction is a key energy scale. Our study demonstrates how Jeff can be controlled and enhanced with direct implications for the optimisation of superconductivity.

Results

Crystal-field environment

Thin films (8–19 nm) of La2CuO4 grown on substrates with different lattice parameters are studied. In this fashion both compressive [LaSrAlO4 (LSAO)] and tensile [NdGaO3 (NGO), (LaAlO3)0.3(Sr2TaAlO6)0.7 (LSAT) and SrTiO3 (STO)] strain is imposed. Strain is defined by ε ≡ (a − a0)/a0 where a and a0 are the in-plane lattice parameters of the thin film and the bulk, respectively. For the above-mentioned samples, ε = −1.25, 1.59, 1.70 and 2.67% is obtained, respectively. The substrates are tuning both the in-plane and out-of-plane lattice parameters of the La2CuO4 films (see Table 1), directly affecting the electronic energy scales of the system. This can be readily observed from the XAS spectra at the copper L3 edge [see Fig. 1a]. A considerable shift (~280 meV) of the Cu L3 edge is found when comparing the compressive strained LCO/LSAO with the tensile strained LCO/STO film. The dd excitations probed through the Cu L3 edge, exhibit a similar systematic shift [see Fig. 1b–d]. The strain-dependent line shape of the dd excitations, points to a change in the crystal-field environment. The double peak structure, known for bulk La2CuO48,9, is also found in our thin films on LSAO, NGO and LSAT substrates. For LCO/STO, however, a more featureless line shape is found, resembling doped La2−xSrxCuO4 (LSCO)10. All together, the shift of the Cu L3 edge and the centre of mass [Fig. 1d] of the dd excitations (along with the line-shape evolution) demonstrate the effectiveness of epitaxial strain for tuning the electronic excitations.

Strain-dependent XAS and RIXS spectra of La2CuO4 films. a Normal incidence (δ = 25°) XAS spectra recorded around the copper L3-edge on La2CuO4 films on different substrates as indicated. b–f display grazing incident copper L3-edge RIXS spectra. In b, c, the dd excitations are shown for different momenta as indicated. For a–c, solid (dashed) lines indicate use of π (σ) polarised incident light. d displays the “centre of mass” of the dd excitations vs. strain ε, for samples as indicated. Each (thin film) point is an average “centre of mass” value of all the spectra in b, c. The bulk La2CuO4 value is extracted from ref. 8. e, f present the low-energy part of RIXS spectra (circular points) with four-component (grey lines) line-shape fits (see text). Notice that the different film systems have, naturally, different elastic components. For visibility all curves in a–e have been given an arbitrary vertical shift. g, h illustrate schematically the scattering geometry. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

Zone-boundary magnons

The low-energy part of the RIXS spectra in the vicinity to the high-symmetry zone-boundary points (1/2, 0) and (1/4, 1/4) are shown in Fig. 1e,f. Generally, the spectra are composed of elastic scattering, a magnon and a weaker multimagnon contribution on a weak smoothly-varying background. In all zone-boundary (ZB) spectra, the magnon excitation is by far the most intense feature. The ZB magnon excitation energy scale, can thus be extracted by the naked eye. Comparing antinodal zone boundary spectra for the compressive (LSAO) and tensile (STO) strained systems [Fig. 1e] reveals a softening of about 60 meV in the STO system. To first order, the magnetic-exchange interaction 2Jeff is setting the antinodal ZB magnon energy scale11,12. Without any sophisticated analysis, we thus can conclude that the magnetic-exchange interaction of LCO thin films can be tuned by strain. At the nodal ZB this effect is much less pronounced [see Fig. 1f], suggesting a strain dependent zone-boundary dispersion. Therefore, the central experimental observations, reported here, are that the crystal-field environment, the magnetic exchange interaction and the magnon zone-boundary dispersions are tunable through strain.

Magnon dispersion

To extract the magnetic-exchange interaction 2Jeff in a more quantitative fashion, three steps are taken. First, a dense grid of RIXS spectra has been measured along the nodal and antinodal directions in addition to a constant-|q//| trajectory connecting the two [see inset of Fig. 2c]. Second, fitting these spectra allows extracting the full magnon dispersion for all the film systems. Finally, these dispersions are parametrised using strong-coupling perturbation theory for the Hubbard model to extract the effective magnetic exchange couplings.

Magnon dispersions of La2CuO4 thin films. a, b display raw RIXS spectra recorded on the LCO/STO thin film system, along the antinodal [1 0] and nodal [1 1] directions, respectively. Red curves represent the data close to the antiferromagnetic zone boundary (AFZB) as shown in the inset in c. Solid lines are fits to the data (see text for detailed description). Notice that elastic scattering is, as expected, enhanced as the specular condition (0,0) is approached. In (c) magnon dispersions of LCO/LSAO and LCO/STO, extracted from fits to raw spectra as in a, b, along three different momentum trajectories (see solid lines in the inset) are presented. Solid lines through the data points are obtained from two-dimensional fits using Hubbard model (see the main text). Error bars are three times the standard deviations extracted from the fits. In (c) Q1 takes different values for each compound due to slightly different incident energies and in-plane lattice parameters, resulting in 0.4437 (0.4611) for LCO/LSAO (LCO/STO). Source data are provided as a Source Data file

Compilations of nodal and antinodal RIXS spectra are shown in Fig. 2a, b and Supplementary Fig. 1 The magnon excitations remain clearly visible even near the zone centre where elastic scattering is typically enhanced. To extract the magnon dispersion, such spectra were fitted using a Gaussian line shape for the elastic scattering and a quadratic function for the weak background. The width of the elastic Gaussian is a free parameter in order to account for a small phonon contribution. Two antisymmetric Lorentzian functions13,14,15 for the magnon and the small multimagnon signals were adopted and convoluted with the experimental resolution function. The quality of the fits can be appreciated from Figs. 1e, f and 2a, b. Generally, the magnon width was found to be comparable to the experimental resolution and independent of momentum, suggesting that the line shape is resolution limited. In contrast to doped systems16,10, magnons of the LCO thin films have a negligible damping and hence the pole of the fitted excitation coincides essentially with the peak maxima.

The extracted magnon dispersions of LCO/STO and LCO/LSAO are displayed in Fig. 2c. The analysis confirms that the magnon bandwidths are significantly different for the two systems. Near the (1/2, 0) zone-boundary point, the LCO/LSAO magnon reaches about 360 meV whereas for LCO/STO a comparative softening of 60 meV is found [Fig. 2c]. This softening is less pronounced near the (1/4, 1/4) zone-boundary point [Fig. 2c], demonstrating that the zone boundary dispersion is also strain dependent [see right inset of Fig. 3c]. Our results thus show a larger ZB dispersion for the LCO/LSAO system.

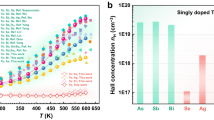

Cuprate energy scales vs. strain. In (a) XAS at Cu L3-edge resonances (left) and the theoretical results for Coulomb interaction U (right) are presented. Experimental and theoretical derived hopping parameters t are presented in b, as indicated. Notice that t is not scaling with the copper-oxygen bond length r−α with α = 6–7 as sometimes assumed51. Jeff as a function of ε = (a − a0)/a0 (where a0 is the in-plane bulk lattice parameter) is presented in c for both theoretical and experimental results. Zone-boundary dispersion EZB, extracted from the Hubbard model, for experimental and theoretical parameters, are presented in the right inset of c as a function of strain ε. Superconducting transition temperature Tc as a function of out-of-plane lattice constant c—for optimally doped LSCO thin films (see Supplementary Table 1)—is presented in the left inset in c. Colour code for the data points in the figure refers to the one shown in c. The error bars for the experimental data are standard deviations extracted from the fits. The theoretical value corresponding to ε ≈ 0.01 (gray symbols) is an artificial sample as described in Table 1. Source data are provided as a Source Data file

Discussion

Different theoretical models have been applied to analyse RIXS spectra of the cuprates. Many of these approaches are purely numerical starting either from a metallic or localised picture17,18. To parameterise experimental results, analytical models are useful. The Hubbard model has, therefore, been frequently used to describe the magnon dispersion of La2CuO410,11,12,19,20. We employ a U − t − t′ − t″ single-band Hubbard model, since t′ and t″ hopping integrals have previously been shown relevant to account in detail for the magnetic dispersion19,20. By mapping onto a Heisenberg Hamiltonian, an analytical expression (see Methods section) for the magnon dispersion ω(q)10,19,20, has been derived.

Before fitting our results, it is useful to consider the ratios U/t, t′/t and t″/t′ for single-layer cuprate systems. In-plane strain will enhance oxygen-p to copper-d orbital hybridisations and hence the effective nearest-neighbour hopping t in the one-band Hubbard model description21. This trend can be calculated from approximate numerical methods such as density functional theory (DFT) [see Fig. 3b]. Besides this increase in band width, oxygen-p orbitals are concomitantly pushed down [Supplementary Fig. 4] and the eg splitting is expected to increase. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 1d, the RIXS dd excitations (“centre of mass”) are pushed to higher energies upon compressive strain, which is consistent with an enhanced eg splitting. This tendency of states moving away from the Fermi-level is generally expected to diminish their ability to screen the Coulomb interaction. Its local component—the Hubbard U—quantifies the energetic penalty of adding a second electron to the half-filled effective \(d_{x^2 - y^2}\) orbital. To a good approximation the evolution of this process is accessible by tracking the Cu 2p63d9 → 2p53d10 XAS resonance. As seen in Fig. 1a and 3a, we find the copper L-edge resonance to shift notably upwards under in-plane compression. This strongly suggests that the energy cost for double occupancies—and hence the Hubbard U—increases under compressive strain, confirming the above rationale.

Beyond the suggested impact on screening, pressure or strain also modify the localisation of the effective \(d_{x^2 - y^2}\) orbital. As a basis-dependent quantity, the Hubbard U is sensitive also to this second mechanism22. To corroborate our experimental finding for the effective Coulomb interaction under in-plane strain, we therefore carried out cRPA calculations for La2CuO4 that include both screening and basis-localisation effects22,23,24,25, (see Methods section). We stress that cRPA is an approximate numerical approach. It is known that correlation effects are underestimated when using only the static limit of the Hubbard interaction26. Indeed the cRPA obtained U ≈ 5t [see Fig. 3a, b and Table 1] is below the expected bandwidth-controlled threshold value. We therefore focus on the relative trends produced by the cRPA. As shown in Fig. 3a, the simulation indeed predicts the Hubbard U to increase with compressive strain. This confirms the above rationale and thus enables us to interpret the XAS Cu L3-edge as a proxy for the variation of the screened Coulomb interaction U. The fact that both U and t increase linearly with compressive strain [Fig. 3a, b] leads us to the Ansatz that the ratio U/t is approximately constant. In the following analysis of the experimental data, we therefore assume U/t = 919 (and t″/t′ = −0.527).

In this fashion, our Hubbard model effectively depends only on t and t′, that constitute our fitting parameters. On a square lattice, one would expect t′/t to remain approximately constant as a function of strain. Indeed, fitting the magnon dispersions, yields that t increases with reduced lattice parameter [Fig. 3b] while t′/t≈−0.4 (see Table 1). This value of t′/t is reasonably consistent with ARPES and LDA derived band structures of the most tetragonal single-layer cuprate systems Hg1201 and Tl220128,29,30,31. Single-band tight-binding models, applied to LSCO, have found significantly lower values of t′/t27,32,33. However, when including hybridisation between the \(d_{x^2 - y^2}\) and \(d_{z^2}\) orbitals, existing in LSCO, one again finds t′/t ≈ −0.431,28,29. The described variation of the hopping t and the Hubbard U translates into a pressure-dependent magnetic exchange interaction Jeff when mapping the Hubbard model (at strong coupling) into a Heisenberg Hamiltonian: Jeff = 4t2/U − 64t4/U3. [see Eq. (6)]. Since U/t ~ const., it is therefore expected that Jeff scales with t. Indeed, as directly visible from the magnon dispersion and our cRPA calculations [Fig. 3c], Jeff increases linearly when going from tensile (ε > 0) to compressive strain (ε < 0).

In LSCO system superconductivity emerges upon hole doping. It is known that for LSCO, the highest Tc is reached when thin films are grown on LSAO substrates34,35. Although higher Tc has been linked to larger c-axis parameter [see left inset of Fig. 3c], the physical origin of this effect has remained elusive. In-plane strain also tunes the c-axis lattice parameter through the Poisson ratio36. The observed evolution of the dd excitations [Fig. 1d] is consistent with a compressive strain-induced enhancement of the eg splitting. It has been argued that this orbital distillation (avoidance of \(d_{x^2 - y^2}\) and \(d_{z^2}\) hybridisation) is beneficial for superconductivity28,29,31. The eg splitting might also indirectly increase Tc by changing the screening of the local Coulomb interaction U, as described above. Antiferromagnetic interactions are a known source for d-wave Cooper pairing37. A link between Jeff and Tc is therefore expected in the large U/t limit38,39,40. Here, we have explicitly demonstrated how the important energy scale Jeff can be tuned through strain. This direct connection between lattice parameters and the magnetic exchange interaction in Mott insulating La2CuO4 provides an engineering principle for the optimisation of high-temperature cuprate superconductivity.

Our study highlights the power of combining oxide molecular beam epitaxial material design with synchrotron spectroscopy. In this particular case of La2CuO4 thin films, it is shown how Coulomb and antiferromagnetic exchange interactions can be artificially engineered by varying the film substrate. In this fashion, direct design control on the Mott insulating energy scales, constituting the starting point for high-temperature superconductivity, has been reached. It would be of great interest to apply this strain-control rationale to doped single-layer HgBa2CuO4+x and Tl2Ba2CuO6+x cuprate superconductors to further enhance the transition temperature Tc.

Methods

Film systems

High quality La2CuO4 (LCO) thin films were grown using Molecular Beam Epitaxy (MBE), on four different substrates: (001)c − SrTiO3 (STO), (001)c − (LaAlO3)0.3(Sr2TaAlO6)0.7 (LSAT), (001)pc − NdGaO3 (NGO) and (001)c − LaSrAlO4 (LSAO). Comparable LCO film thickness, for STO and LSAT and for NGO & LSAO, were used (Table 1). For such thin films, the in-plane lattice parameter afilm is set by the substrate lattice a indicated in Table 1. Compared to bulk LCO, the substrate STO, LSAT and NGO induce tensile strain whereas LSAO generates compressive strain. Film thicknesses were extracted from fit to the 2θ scans (see Supplementary Fig. 2 using an x-ray diffraction tool as in ref. 41.

Spectroscopy experiments

X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) and resonant inelastic x-ray scattering (RIXS) were carried out at the ADRESS beamline42,43, of the Swiss Light Source (SLS) synchrotron at the Paul Scherrer Institut. All data were collected at base temperature (~20 K) of the manipulator under ultra high vacuum (UHV) conditions, 10−9 mbar or better. RIXS spectra were acquired in grazing exit geometry with both linear horizontal (π) and linear vertical (σ) incident light polarisation with a scattering angle 2θ = 130° [see Fig. 1g,h]. An energy resolution half width at half maximum (HWHM) of 68 meV—at the Cu L3 edge—was extracted from the elastic scattering signal. Momentum q = q// = (h, k) is expressed in reciprocal lattice units (rlu).

Hubbard model

A single-band Hubbard model is adopted in the present study. Being important to consider a second-neighbour hopping integral—for La2CuO4 compound19,20—in order to fully describe the magnon dispersion relation11,12, we consider the following Hamiltonian:

where t, t′ and t″ are the first-nearest, second-nearest and third-nearest-neighbour hopping integrals; U is the on-site Coulomb interaction integral; \(c_{i,\sigma }^\dagger\) and ci,σ are the creation and annihilation operators at the site i and spin σ = ↑,↓; and \(n_{i,\sigma } \equiv c_{i,\sigma }^\dagger c_{i,\sigma }\) is the density operator at the site i with spin σ. The sum (for the hopping process) is done over the first-nearest \(\left\langle \star \right\rangle\), second-nearest \(\left\langle {\left\langle \star \right\rangle } \right\rangle\) and third-nearest neighbour sites \(\left\langle {\left\langle {\left\langle \star \right\rangle } \right\rangle } \right\rangle\).

Using this Hamiltonian at strong coupling it is possible to obtain19,20, a magnon dispersion of the form:

The momentum dependence of A and B can be expressed in terms of trigonometric functions

such that10:

and

where \(J_1 = \frac{{4t^2}}{U}\), \(J_2 = \frac{{4t^4}}{{U^3}}\), \(J_1{\!\!{\prime}} = \frac{{4t{{\prime}^ 2}}}{U}\), \(J_2{\!\!{\prime}} = \frac{{4t{{\prime^4}}}}{{U^3}}\), \(J_1{\!\!{{\prime}\!{\prime}}} = \frac{{4t{{{\prime}\!{\prime}}^2}}}{U}\) and \(J_2{\!\!{{\prime}\!{\prime}}} = \frac{{4t{{{\prime}\!{\prime}}^4}}}{{U^3}}\). When neglecting higher order terms (i.e., terms in \(J_2{\!\!{\prime}}\), \(J_2{\!\!{{\prime}\!{\prime}}}\) and \(J_1{\!\!{\prime}} J_1{\!\!{{\prime}\!{\prime}}}\)) and considering t″ = −t′/2, it is possible to obtain an approximated solution for the zone-boundary dispersion EZB10:

if:

Furthermore, it is possible to see19, that with such a model, which considers also the cyclic hopping terms, the effective exchange interaction can be written as:

if considering only the first neighbour hopping t.

DFT and cRPA calculations

We compute the electronic structure of tetragonal bulk La2CuO4 for lattice constants and atomic positions corresponding to the experimentally investigated thin films (see Table 1). For simplicity, tetragonal structures were considered with the ratio between copper to apical oxygen dO2 (copper to lanthanum dLa) distance and the c axis kept constant to the bulk values dO2/c = 0.18(4) (dLa/c = 0.36(1))44. We use a full-potential linear muffin-tin orbitals (FPLMTO) implementation45 in the local density approximation (LDA) and construct maximally localised Wannier functions46 for the Cu \(d_{x^2 - y^2}\) orbital. Hopping elements t, t′ and t″ are then extracted by fitting a square-lattice dispersion to high-symmetry points. Next, the static Hubbard U = U(ω = 0) is computed using the constrained random-phase approximation (cRPA)47 in the Wannier setup48 for entangled band-structures49. Finally, the effective magnetic exchange interaction Jeff is determined using the strong-coupling expression Eq. (6).

The above procedure is an approximate way to account for the screening of the Coulomb interaction v provided by the electronic degrees of freedom that are omitted when going to a description in terms of an effective one-band Hubbard (and, ultimately, Heisenberg) model. In other words, v has to be screened by all particle-hole polarisations that are not fully contained in the subspace spanned by the \(d_{x^2 - y^2}\) Wannier functions that define the low-energy model. In cRPA, this partial polarisation is computed within RPA, meaning that bare particle-hole bubble diagrams (Lindhard function) are summed up to all orders in the interaction. Constraining the polarisation comes with the benefit that it is precisely the left-out low-energy excitations that display the most correlation effects, potentially leading to important vertex corrections beyond the RPA. Indeed, solving the many-body model that we are setting up through the hoppings t, t′, etc. and the Hubbard U would require approaches beyond the RPA.

Let us briefly describe how pressure can modify the partially screened local Coulomb interaction U: First, pressure-induced changes in hoppings and crystal-fields modify the solid’s polarisation (dielectric function) and, hence, how efficiently the Coulomb interaction is screened. This effect is very material specific and can lead to both, an enhancement or a diminishing of U23,24,25. Second, the parameters of the Hubbard model are basis-dependent quantities. As a result the matrix element U also depends on the extent in real-space of the \(d_{x^2 - y^2}\)-derived Wannier basis. Quite counter-intuitively, a pressure-induced delocalisation of Wannier functions generally leads to increased local interactions22. This trend can be illustrated by looking at the pressure evolution of the matrix element of the bare (unscreened) Coulomb interaction v = e2/r in the Wannier basis: Indeed, as reported in Table 1, v increases with shrinking lattice constant. In our case of tetragonal La2CuO4, both effects (screening and basis localisation) promote the same tendency: an increase of the Hubbard U under compression.

References

Imada, M., Fujimori, A. & Tokura, Y. Metal-insulator transitions. Rev. Mod. Phys. 70, 1039–1263 (1998).

Wigner, E. & Huntington, H. B. On the possibility of a metallic modification of hydrogen. J. Chem. Phys. 3, 764 (1935).

Friedemann, S. et al. large fermi surface of heavy electrons at the border of Mott insulating state in NiS2. Sci. Rep. 6, 25335 EP (2016).

Gati, E. et al. Breakdown of Hooke’s law of elasticity at the Mott critical endpoint in an organic conductor. Sci. Adv. 2, e1601646 (2016).

Lee, P. A., Nagaosa, N. & Wen, X.-Gang Doping a Mott insulator: physics of high-temperature superconductivity. Rev. Mod. Phys. 78, 17–85 (2006).

Hardy, F. et al. Enhancement of the critical temperature of HgBa2CuO4+δ by applying uniaxial and hydrostatic pressure: implications for a universal trend in cuprate superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 167002 (2010).

Wang, S. et al. Strain derivatives of T c in HgBa2CuO4+δ: The CuO2 plane alone is not enough. Phys. Rev. B 89, 024515 (2014).

Moretti Sala, M. et al. Energy and symmetry of dd excitations in undoped layered cuprates measured by Cu L 3 resonant inelastic x-ray scattering. New J. Phys. 13, 043026 (2011).

Peng, Y. Y. et al. Influence of apical oxygen on the extent of in-plane exchange interaction in cuprate superconductors. Nat. Phys. 13, 1201 EP (2017).

Ivashko, O. et al. Damped spin excitations in a doped cuprate superconductor with orbital hybridization. Phys. Rev. B 95, 214508 (2017).

Coldea, R. et al. Spin waves and electronic interactions in La2CuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 5377–5380 (2001).

Headings, N. S., Hayden, S. M., Coldea, R. & Perring, T. G. Anomalous high-energy spin excitations in the high-T c superconductor-parent antiferromagnet La2CuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 247001 (2010).

Le Tacon, M. et al. Intense paramagnon excitations in a large family of high-temperature superconductors. Nat. Phys. 7, 725–730 (2011).

Monney, C. et al. Resonant inelastic x-ray scattering study of the spin and charge excitations in the overdoped superconductor La1.77Sr0.23CuO4. Phys. Rev. B 93, 075103 (2016).

Lamsal, J. & Montfrooij, W. Extracting paramagnon excitations from resonant inelastic x-ray scattering experiments. Phys. Rev. B 93, 214513 (2016).

Dean, M. P. M. et al. Persistence of magnetic excitations in La2−xSrxCuO4 from the undoped insulator to the heavily overdoped non-superconducting metal. Nat. Mater. 12, 1019–1023 (2013).

Nomura, T. Theoretical study of l-edge resonant inelastic x-ray scattering in La2CuO4 on the basis of detailed electronic band structure. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 84, 094704 (2015).

Jia, C. J. et al. Persistent spin excitations in doped antiferromagnets revealed by resonant inelastic light scattering. Nat. Commun. 5, 3314 (2014).

Delannoy, J.-Y. P., Gingras, M. J. P., Holdsworth, P. C. W. & Tremblay, A.-M. S. Low-energy theory of the t−t′−t−U Hubbard model at half-filling: Interaction strengths in cuprate superconductors and an effective spin-only description of La2CuO4. Phys. Rev. B 79, 235130 (2009).

Dalla Piazza, B. et al. Unified one-band Hubbard model for magnetic and electronic spectra of the parent compounds of cuprate superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 85, 100508 (2012).

Abrecht, M. et al. Strain and high temperature superconductivity: unexpected results from direct electronic structure measurements in thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 057002 (2003).

Tomczak, J. M., Miyake, T., Sakuma, R. & Aryasetiawan, F. Effective Coulomb interactions in solids under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 79, 235133 (2009).

Tomczak, J. M., Miyake, T. & Aryasetiawan, F. Realistic many-body models for manganese monoxide under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 81, 115116 (2010).

Di Sante, D. et al. Realizing double Dirac particles in the presence of electronic interactions. Phys. Rev. B 96, 121106 (2017).

Kim, B., Liu, P., Tomczak, J. M. & Franchini, C. Strain-induced tuning of the electronic coulomb interaction in 3d transition metal oxide perovskites. Phys. Rev. B 98, 075130 (2018).

Werner, P., Sakuma, R., Nilsson, F. & Aryasetiawan, F. Dynamical screening in La2CuO4. Phys. Rev. B 91, 125142 (2015).

Yoshida, T. et al. Systematic doping evolution of the underlying Fermi surface of La2−xSrxCuO4. Phys. Rev. B 74, 224510 (2006).

Sakakibara, H., Usui, H., Kuroki, K., Arita, R. & Aoki, H. Two-orbital model explains the higher transition temperature of the single-layer Hg-cuprate superconductor compared to that of the La-cuprate superconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 057003 (2010).

Sakakibara, H., Usui, H., Kuroki, K., Arita, R. & Aoki, H. Origin of the material dependence of T c in the single-layered cuprates. Phys. Rev. B 85, 064501 (2012).

Platé, M. et al. Fermi surface and quasiparticle excitations of overdoped Tl2Ba2CuO6+δ. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 077001 (2005).

Matt, C. E. et al. Direct observation of orbital hybridisation in a cuprate superconductor. Nat. Commun. 9, 972 (2018).

Chang, J. et al. Anisotropic breakdown of Fermi liquid quasiparticle excitations in overdoped La2−xSrxCuO4. Nat. Commun. 4, 2559 (2013).

Chang, J. et al. Anisotropic quasiparticle scattering rates in slightly underdoped to optimally doped high-temperature La2−xSrxCuO4. Phys. Rev. B 78, 205103 (2008).

Sato, H. & Naito, M. Increase in the superconducting transition temperature by anisotropic strain effect in (001) La1.85Sr0.15CuO4 thin films on LaSrAlO4. Phys. C. 274, 221–226 (1997).

Locquet, J. & Williams, E. Epitaxially induced defects in Sr- and O-doped La2CuO4 thin films grown by MBE: implications for transport properties. Acta Phys. Pol. A 92, 69–84 (1997).

Nakamura, F. et al. Role of two-dimensional electronic state in superconductivity in La2−xSrxCuO4. Phys. Rev. B 61, 107–110 (2000).

Scalapino, D. J. A common thread: the pairing interaction for unconventional superconductors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 84, 1383–1417 (2012).

Ofer, R. et al. Magnetic analog of the isotope effect in cuprates. Phys. Rev. B 74, 220508 (2006).

Ellis, D. S. et al. Correlation of the superconducting critical temperature with spin and orbital excitations in (CaxLa1−x)(Ba1.75−xLa0.25+x)Cu3Oy as measured by resonant inelastic x-ray scattering. Phys. Rev. B 92, 104507 (2015).

Fratino, L., Sémon, P., Sordi, G. & Tremblay, A.-M. S. An organizing principle for two-dimensional strongly correlated superconductivity. Sci. Rep. 6, 22715 (2016).

Lichtensteiger, C. InteractiveXRDFit: a new tool to simulate and fit X-ray diffractograms of oxide thin films and heterostructures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 51, 1745–1751 (2018).

Ghiringhelli, G. et al. SAXES, a high resolution spectrometer for resonant x-ray emission in the 400-1600eV energy range. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 77, 113108 (2006).

Strocov, V. N. et al. High-resolution soft X-ray beamline ADRESS at the Swiss Light Source for resonant inelastic X-ray scattering and angle-resolved photoelectron spectroscopies. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 17, 631–643 (2010).

Radaelli, P. G. et al. Structural and superconducting properties of La2−xSrxCuO4 as a function of Sr content. Phys. Rev. B 49, 4163–4175 (1994).

Methfessel, M., van Schilfgaarde, Mark & Casali, R. I. A full-potential LMTO method based on smooth Hankel functions, in electronic structure and physical properties of solids: the uses of the LMTO method, Lecture Notes in Physics, Dreysse, H. Ed. 535, 114–147 (2000).

Marzari, N., Mostofi, A. A., Yates, J. R., Souza, I. & Vanderbilt, D. Maximally localized Wannier functions: theory and applications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 84, 1419–1475 (2012).

Aryasetiawan, F. et al. Frequency-dependent local interactions and low-energy effective models from electronic structure calculations. Phys. Rev. B 70, 195104 (2004).

Miyake, T. & Aryasetiawan, F. Screened Coulomb interaction in the maximally localized Wannier basis. Phys. Rev. B 77, 085122 (2008).

Miyake, T., Aryasetiawan, F. & Imada, M. Ab initio procedure for constructing effective models of correlated materials with entangled band structure. Phys. Rev. B 80, 155134 (2009).

Vasylechko, L. et al. The crystal structure of NdGaO3 at 100K and 293K based on synchrotron data. J. Alloy. Compd. 297, 46–52 (2000).

Häfliger, P. S. et al. Quantum and thermal ionic motion, oxygen isotope effect, and superexchange distribution in La2CuO4. Phys. Rev. B 89, 085113 (2014).

Acknowledgements

O.I., M.H. and J.C. acknowledge support by the Swiss National Science Foundation under grant No. BSSGI0_155873 and through the SINERGIA network Mott Physics Beyond the Heisenberg Model. D.E.N., E.P., Y.T. and T.S. acknowledge support by the Swiss National Science Foundation through its Sinergia network Mott Physics Beyond the Heisenberg Model MPBH (Research Grant CRSII2_160765/1) and the NCCR MARVEL (Research Grant 51NF40_141828). This work was performed at the ADRESS beamline of the SLS at the Paul Scherrer Institut, Villigen PSI, Switzerland. We thank the ADRESS beamline staff for technical support. C.A. and M.R.B. were is supported by Air Force Office of Scientific Research grant No. FA9550-09-1-0583. N.E.S. and H.M.R. acknowledge the Swiss National Science foundation under grant No. 200021-169061. W.W. and N.B.C. were supported by the Danish Center for Synchrotron and Neutron Science (DanScatt). K.M.S. and H.I.W. were supported by the Air Force Office of Scientific Research grant No. FA9550-15-1-0474.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.I.W., C.A., C.L., M.G., M.R.B. and K.M.S. grew and characterised the La2CuO4 thin films. O.I., M.H., W.W., N.B.C., D.E.N., E.P., Y.T., T.S. and J.C. executed the XAS and RIXS experiments. O.I., W.W. and N.B.C. performed the RIXS and XAS data analysis. N.E.S. and H.M.R. developed the Hubbard model. J.M.T. carried out the DFT and cRPA calculations. All authors contributed to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ivashko, O., Horio, M., Wan, W. et al. Strain-engineering Mott-insulating La2CuO4. Nat Commun 10, 786 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08664-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08664-6

This article is cited by

-

Possible strain-induced enhancement of the superconducting onset transition temperature in infinite-layer nickelates

Communications Physics (2023)

-

Uniaxial pressure induced stripe order rotation in La1.88Sr0.12CuO4

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Evolution of electronic and magnetic properties of Sr2IrO4 under strain

npj Quantum Materials (2022)

-

Anomalous Ferromagnetism of quasiparticle doped holes in cuprate heterostructures revealed using resonant soft X-ray magnetic scattering

Nature Communications (2022)

-

Design of Complex Oxide Interfaces by Oxide Molecular Beam Epitaxy

Journal of Superconductivity and Novel Magnetism (2020)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.