Abstract

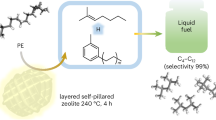

The search for porous materials with strong Brønsted acid sites for challenging reactions has long been of significant interest, but it remains a formidable synthetic challenge. Here we demonstrate a cage extension strategy to construct chiral permanent porous hydrogen-bonded frameworks with strong Brønsted acid groups for heterogeneous asymmetric catalysis. We report the synthesis of two octahedral coordination cages using enantiopure 4,4’,6,6’-tetra(benzoate) ligand of 1,1’-spirobiindane-7,7’-phosphoric acid and Ni4/Co4-p-tert-butylsulfonylcalix[4]arene clusters. Intercage hydrogen-bonds and hydrophobic interactions between tert-butyl groups direct the hierarchical assembly of the cages into a permanent porous material. The chiral phosphoric acid-containing frameworks can be high efficient and recyclable heterogeneous Brønsted acid catalysts for asymmetric [3+2] coupling of indoles with quinone monoimine and Friedel-Crafts alkylations of indole with aryl aldimines. The afforded enantioselectivities (up to 99.9% ee) surpass those of the homogeneous counterparts and compare favorably with those of the most enantioselective homogeneous phosphoric acid catalysts reported to date.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Porous solid materials with Brønsted acid sites (BASs) have been extensively used as environmentally friendly heterogeneous catalysts in chemical and petrochemical processes1. Continued efforts have been focused on the search for new solid Brønsted acid catalysts for challenging and practically important reactions2,3,4,5 including asymmetric reactions, which afford enantiopure and high value-added chemicals still catalyzed by homogeneous catalysts6. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) have recently been explored as asymmetric catalysts for their structural diversity and tunable porosity7,8,9,10,11,12, with the most efficient examples all containing organic linkers derived from privileged chiral Lewis acid catalysts11,12. By contrast, there are only few reports on Brønsted acidic MOFs that are catalytically active but with low enantioselectivities (6–84% ee)13,14,15,16. It is hard to make chiral MOFs featuring strong BASs from sulfonated or phosphonated organocatalysts because they are often the ligating functionality of choice for framework construction7,17,18. For example, arylphosphocarboxylates can form stronger bonds with metal ions than pure carboxylates, but they tend to form dense frameworks without BASs through both carboxylate and phosphonate groups17,18. Remarkably, very recently, hydrogen-bonded organic frameworks (HOFs) constructed by linking organic molecules or metal-complexes through intermolecular hydrogen bonds have become an alternative to extended framework materials19,20,21,22,23. The mild conditions typically used to synthesize HOFs allow the rational design of crystalline frameworks with reactive functional groups such as phosphonic acids through judicious choices of building blocks, thus making them interesting complements to MOFs24,25,26. In this work, we demonstrated that strong chiral BASs can be directly built in HOFs through a cage extension strategy for heterogeneous asymmetric catalysis.

Metal-organic cages are molecular containers27,28,29,30,31 and are attractive building blocks for construction of supramolecular porous materials as they provide high chemical and structural diversity and possess inherent porosity and functions27,32,33,34. Although their structures are intrinsically porous, the cage solids generally collapse upon solvent removal due to the lack of strong bonding between cages27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. Hydrogen-bonding interactions between coordination cages have been observed before35,36,37,38,39,40. For example, Eddaoudi et al. reported two porous materials with zeolite-like topologies constructed from metal-imidazolate cubes through the vertex-to-vertex hydrogen bonding35. Since then, more hydrogen-bonded frameworks based on cubic metal-imidazolate cages and tetrahedral metal-carboxylate cages have been reported36,37,38,39,40, but only one of them was capable of retaining its crystalline structure upon desolvation40. Here we report how to address this issue through careful design of coordination cages covering with two types of acid groups capable of forming strong hydrogen bonds to another, as exemplified in the context of hierarchical construction of chiral permanent porous HOFs based on octahedral cages.

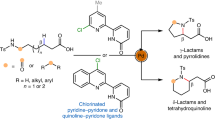

Chiral phosphoric acids derived from axially diols such as 1,1′-binaphthol (BINOL)41 and 1,1′-spirobiindane-7,7′-diol (SPINOL)42 have found widespread application as Brønsted acid catalysts in enantioselective transformations involving imines, such as Mannich43, Friedel-Crafts (F-C)44, Pictet-Spengler45, and aza-Diels-Alder reactions46. On the other hand, sulfonylcalix[4]arenes react with metal ions to generate a shuttlecock-like tetrametallic cluster, which is an ideal four-connected node in assembling nanosized cages by binding to auxiliary organic linkers47,48. Following the construction principles of coordination cages, we chose the M4-calixarene as the square unit and the multitopic ligand 4,4′,6,6′-tetrakis(4-benzoic acid)-1,1′-spinol phosphonate (H4L) as the potential triangular unit (Fig. 1a). Intercage hydrogen bonds formed between carboxylic and phosphoric acid groups direct the assembly of octahedral cages into a robust porous HOF. The phosphoric acid-containing solids can be highly enantioselective heterogeneous catalysts for [3+2] coupling of indoles with quinone monoimine and F-C alkylation of indole with aryl aldimines, with enantioselectivities surpassing the homogeneous counterparts and comparing favorably with the most stereoselective homogeneous phosphoric acid catalysts that have been reported so far.

Assembly procedures. a Self-assembly of cages 1-Ni and 1-Co (only half of the HL3− ligand are shown in the cage for clarity). b The single-crystal structure of the octahedral cage in 1-Ni and c the space-filling model with an elliptical shape viewed along the short axis (sky-blue, Ni; green, P; yellow, S; gray, C; red, O). The cavities are highlighted by colored spheres

Results

Synthesis and characterization

The ligand H4L was prepared in an overall 58% yield through four steps by utilizing enantiopure spinol49 as starting material. Heating a mixture of H4L, H4TBSC and NiCl2·6H2O or Co(NO3)2·6H2O (a 1:1:10 molar ratio) in DMF and water in the presence of 0.1 M HCl solution at 80 °C for 72 h afforded rectangular-shaped crystals of {[M4(μ4-H2O)(TBSC)]6[HL]8}·G (M = Ni and Co for 1-Ni, 1-Co, respectively) in good yields (Supplementary Figure 8). The formulations of them were supported by the results of IR spectroscopy (Supplementary Figure 12), microanalysis, and thermogravimetric analysis (TGA). The products were insoluble in H2O and common organic solvents including MeOH, DMF, and DMSO (Supplementary Figure 10). However, we were capable of isolating the discrete octahedral cages in MeOH by adding a little amount of formic acid, as evidenced by quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (Q-TOF-MS), UV-vis and circular dichroism (CD) spectra (Supplementary Figures 6, 7 and 11). The phase purity of the bulk samples was established by comparison of their observed and simulated powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Figure 14). The slight discrepancy between the calculated and experimental patterns probably result from framework distortion caused by partial loss of guest molecules of the samples after being exposed to air.

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction showed that (S)-1-Ni crystallizes in the chiral triclinic P1 space group, with a whole cage in the asymmertic unit. The structure has no crystallographic symmetry and is comprised of six shuttlecock-like tetranuclear Ni4-TBSC nodes and eight HL3− linkers. Three of the four crystallographically independent carboxylate groups are deprotonated and coordinate to six Ni centers from three Ni4-TBSC clusters in a bidentate fashion, while the fourth carboxylate group remains protonated and uncoordinated to the Ni4-TBSC vertex (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Figure 1). Each Ni(II) center adopts an octahedral geometry coordinated by one sulfonyl and two phenoxo oxygen atoms from the deprotonated TBSC4− ligand, two carboxylate oxygen atoms from two different HL3− ligands and one μ4-H2O molecule. Thus, six Ni4-TBSC clusters as the four-connected vertexes are linked by eight tritopic HL3− linkers as the faces to form a truncated octahedral cage with an elliptical shape. A space-filling representation of 1-Ni clearly shows the formation of a porous cage with a substantially elliptical shape (Fig. 1c). The cage has totally eight pairs of free phosphoric and benzoic acid groups, each of which located on one of the eight faces of an octahedron. The overall size of the cage is ~4.0 × 4.0 × 5.1 nm3, and the size of the inner cavity is 2.1 × 2.1 × 3.2 nm3 (excluding Van der Waals radius). The cage featuring a large internal volume (~3339 Å3) contains two kinds of apertures. The large one has a diagonal distance of 1.2 ×1.9 nm2 and the small one has a diagonal distance of 1.0 × 1.5 nm2. There are many examples of discrete coordination cages with large cavities that contain functional groups on their periphery surfaces, but none of them are functionalized with carboxylic or phosphoric acid groups29,30,31.

Each cage utilizes two pairs of carboxylic and phosphoric acid groups to form four O–H···O intermolecular hydrogen bonds with two pairs of phosphoric and carboxylic acids from four neighboring cages, with other six pairs of the organic acid groups not involved in hydrogen bonding (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Figures 2 and 3). The short O···O distances of 2.608(1) and 2.695(1) Å are indicative of strong hydrogen-bonding interactions50. Meanwhile, each TBSC unit in the cage interacts with five neighboring TBSC units from five different cages forming complex intercluster π–π, CH···π, CH···O, and C–H···H–C interactions (Fig. 2b). As a result, two kinds of extrinsic octahedral cages with a maximum diameter of 1.5 and 0.36 nm, respectively, are generated via the arrangement of six TBSC units of six cages and eight triangular faces of eight cages, as shown in Fig. 2c and Supplementary Figure 4. Intercluster interactions thus direct the assembly of molecular octahedral cages into an extended 3D porous supramolecular framework functionalized with phosphoric and benzoic acid groups (Fig. 2d).

Crystal structures. a Four hydrogen bonds formed between five adjacent cages. b A hydrophobic cavity formed by six TBSC moieties from six cages. c The 3D HOF structure showing octahedral cages interconnected by two types of newly generated cages. d Simplified 3D packing structure. The cavities are highlighted by colored spheres

1-Co is isostructural to 1-Ni and adopts a similar porous cage structure that is built from Co4-TBSC clusters and HL3− linkers with an inner cavity size of 2.1 × 2.1 × 3.2 nm3 (excluding Van der Waals radius). The cage 1-Co also features eight pairs of carboxylic and phosphoric acid groups, directed outside the cage, thus serving as a building block which extends to a 3D polymer. Calculations using PLATON show that both 1-Co and 1-Ni have about ∼70% of the total volume available for guest inclusion51. These volumes are presumably filled with solvent molecules such as DMF and/or H2O, which are unfortunately highly disordered and could not be located by X-ray crystallography. It should be noted that the chiral phosphoric acid groups of the HL3− ligands are exposed to the interstitial pores accessible to guest molecules. Porous solids of this type may offer great opportunities for studies of supramolecular chemistry and host-guest interactions, and the present two cages are attractive examples of supramolecular assemblies decorated with chiral functional groups that have been characterized by single-crystal X-ray crystallography52,53,54,55,56,57. To the best of our knowledge, they represent the first two examples of crystalline porous frameworks with channels decorated with two types of BASs58,59. In addition, we were also capable of preparing single crystals of racemic 1-Ni and 1-Co from the racemic ligand H4L under similar reaction conditions. X-ray diffraction revealed each of them adopts a porous hydrogen-bonded 3D structure that is built from racemic [M4(μ4-H2O)(TBSC)]6[HL]8}cages (the result will be reported in the near future). To evaluate the generality of our synthetic approach to HOFs, we synthesized a new 4,4′,6,6′-tetra(1-naphthoate) ligand of 1,1′-spirobiindane-7,7′-phosphoric acid (H4L′), as shown in Supplementary Figure 5. As expected, heating a DMF/H2O solution containing H4L′, H4TBSC, and Co(NO3)2·6H2O afforded a similar octahedral cage 1-Co', as revealed by single-crystal X-ray diffraction (Supplementary Figure 5). Strong intercluster hydrogen bonding and supramolecular interactions direct the packing of the cages into a 3D porous HOF. So, the present synthetic strategy may hold great promise for preparing more cage-based expanded structures. Further work on related porous materials is ongoing in this lab.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra of 1-Ni and 1-Co made from R and S enantiomers of the H4L ligand are mirror images of each other, indicative of their enantiomeric nature (Supplementary Figure 11). TGA revealed that the guest molecules could be readily removed in the temperature range from 50 to 150 °C and the frameworks started to decompose at about 420 °C (Supplementary Figure 9). Removal of the guest molecules led to structural distortion of the framework, thereby displaying some differences in relative peak intensities in the PXRD patterns for the evacuated and pristine samples (Fig. 3a). Their permanent porosity was demonstrated by N2 adsorption measurements at 77 K. After desolvation of the n-hexane-exchanged samples, both 1-Ni and 1-Co exhibit a type I sorption behavior, with a Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area of 1239 and 1192 m2 g−1, respectively (Fig. 3b).

Heterogeneous asymmetric catalysis

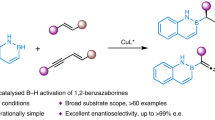

The permanent porosity and regularly distributed phosphoric acid sites of the solids prompted us to explore their utilization as heterogeneous catalysts. In each cage, two of eight phosphoric moieties are engaged in H-bonding interactions, and the remaining six phosphoric acids are available for catalysis. [3+2] coupling of 3-substituted indoles with quinone monoimine catalyzed by enantiopure Brønsted acid catalysts offers direct access to optically active benzofuroindoline derivatives that are commonly found in a diverse array of important natural alkaloids60. So, our initial reaction was carried out with 3-methyl indole and 4-methyl-N-(4-oxocyclohexa-2,5-dienylidene)benzenesulfonamide. After screening a variety of reaction conditions including solvent, temperature and catalyst loading (Supplementary Table 5), we found that, in the presence of 0.04 mol% loading of 1-Ni (0.04 μmol cage), the reaction proceeded smoothly to give the benzofuroindoline in 92% yield and 99.9% ee within 14 h (Table 1, entry 1 and Supplementary Figure 15). Further lowering the catalyst loading to 0.02 mol% led to a decrease in both the yield and ee value (Supplementary Table 5, entry 12).

With the optimal reaction conditions in hand, we next examined the substrate scope with respect to various 3-substituted indoles. As shown in Table 1 (entries 2–7), the electronic nature or positions of the substituent on the indole appeared to have limited effects on the catalytic results, and the benzofuroindolines were afforded in 83–95% yields and 91–99% ee. The absolute configurations of the products were established to be S by the comparison of their HPLC peaks with the reported results60. The chiral nature of the product is dominated by the handedness of the catalyst, as evidenced by that reaction catalyzed by (R)-1-Ni gave the R enantiomer over the S enantiomer (Table 1, entry 11). We also examined the catalytic activity of 1-Co for the coupling reactions. Under identical conditions, the reactions afforded the products with almost the same yields and enantioselectivities as those obtained with 1-Ni (Table 1, entries 12–14), indicating that the M4(μ4-H2O)(TBSC) nodes in the cages have no obvious effect on the catalytic performance. In addition, when benzoic acid was used as catalyst, no coupling reaction of 3-methyl indole and quinone monoimine was observed (Table 1, entry 15), indicating the reaction was catalyzed by the immobilized phosphoric acids. We also performed the coupling reaction involving deprotonation of 1-Ni by adding a little amount of Et3N or NH3·H2O, but did not detect any targeted product even after 72 h, further indicating the catalysis emanates from the phosphoric acid sites.

Multiple experiments were conducted to study the heterogeneity and recyclability of the solid catalyst. First, by using 3-methyl indole as substrate, removal of 1-Ni by filtration after 2 h completely shut down the reaction, affording only 45% total conversion upon stirring for 14 h. This indicates that there exists no active species in the reaction solution. Second, upon completion of the reaction, the catalyst could be readily recovered from the catalytic reaction via centrifugation, and used repeatedly with negligible deterioration in yields and enantioselectivities for the following 10 runs (Fig. 4a). After ten cycles, the recovered catalyst retained crystallinity and porosity, as indicated by the PXRD and BET surface area (1069 m2 g−1) (Fig. 3). Third, inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometric (ICP-MS) analysis of the product solution showed that <0.003% of the nickel had leached into the solvent per cycle, either as molecular species or as particles too small to be removed by filtration through Celite.

Recycle and confinement effect. a Recycling tests of the HOF 1-Ni catalyst in the [3+2] coupling reaction of 3-methyl indole with quinone monoamine. b Plots of the [3+2] coupling reaction of 3-methyl indole with quinone monoimine at different catalyst loadings (catalyst loadings of Me4L and 1-Ni* are 6 and 0.75 times of HOF 1-Ni, respectively)

To ascertain that the substrates access the internal phosphoric acid sites via the open channels, we have examined three indole derivatives of different sizes. Molecular mechanics simulations indicated that these indoles have estimated sizes ranging from 6.5 × 11.5 Å2 to 6.5 × 15.2 Å2 (Supplementary Figure 16). As expected, the substrate sizes have no obvious effects on the efficiency for the discrete cage 1-Ni* or Me4L catalyzed [3+2] coupling reactions (Table 1, entries 20–22). In contrast, the yields of the reaction products catalyzed by 1-Ni greatly depend on the substituent size: as the size of the indoles increases, the yield of the final product steadily decreases (65, 37, and 9%; Table 1, entries 8–10). Specially, only a 9% yield of the desired product was observed for the very bulky reactant 3-(2-phthalimidoethyl)-indole, which was much lower than 56% and 64% yields obtained with 1-Ni* and Me4L, respectively, presumably because it cannot access the catalytic sites in the cavity through the windows (10.5 × 14 Å2) due to its large diameters (6.5 × 15.2 Å2). This finding indicated that the catalytic reaction may mainly occur in the pores of the solid catalyst.

To further study the confinement effect of the porous structure on phosphoric acids, the catalytic performance of the homogeneous controls 1-Ni* and Me4L were tested. Under otherwise identical conditions, with the equal loading of phosphoric acid sites, both 1-Ni* and Me4L can catalyze [3+2] coupling of 3-methyl indole with 4-methyl-N-(4-oxocyclohexa-2,5-dienylidene) benzenesulfonamide affording 94% yield with 89% ee and 79% yield with 78% ee of the products, respectively (Table 1, entry 16). Therefore, the HOF 1-Ni displayed higher enantioselectivity (99.9% ee) than the homogeneous controls 1-Ni* and Me4L under otherwise identical reaction conditions. Similar behaviors were observed for other substrates (Table 1, entries 17–19). The increased ee values may arise from geometrical constraints imposed by the chiral micro-environments around the phosphoric acids, which may restrict molecular motion to improve enantiodiscrimination. As shown in Fig. 4b, the difference in catalytic performances of 1-Ni, 1-Ni*, and Me4L became large at a low catalyst loading. Specially, when the loading was decreased from 0.04 to 0.02 mol%, 1-Ni can give 72% yield with 94% ee of the product, while the homogeneous controls 1-Ni* and Me4L only gave 75% yield with 87% ee and 34% yield with 53% ee, respectively. Continuing to decrease the loading to 0.01 mol%, 1-Ni also can afford 43% yield with 90% ee, which obviously surpass the results catalyzed by 1-Ni* and Me4L (51% yield with 76% ee and 6% yield with 32% ee, respectively). When the catalyst loading reach to a very small magnitude of 0.005 mol%, the molecular catalyst Me4L nearly lost its activity, however, the discrete cage 1-Ni* and the HOF catalyst 1-Ni still can achieve 35% yield with 68% ee and 29% yield with 88% ee, respectively. The catalytic performance became poor on lowing the loading of Me4L, probably due to conversion of catalytic sites into less active and selective species in dilute solutions. So, confinement of catalytically active Brønsted acids in the cage, especially the cage-based solid can stabilize the organocatalyst and even enhance the catalyst activity and stereoselectivity at a very low catalyst loading. It should be noted that increasing the catalysts loading from 0.04 to 0.05 mol% cannot obviously increase yield and enantioselectivity (80% yield with 80% ee for Me4L, 94% yield with 90% ee for 1-Ni*, and 92% yield with 99.9% ee for 1-Ni).

1-Ni can also catalyze the asymmetric F-C alkylations of indole and aryl aldimines, which provides a completely atom-economical access to enantiopure 3-indolylmethanamine derivatives44,61, key components of many biologically active natural and natural-like products. Under optimized conditions (Supplementary Table 6), the reaction of N-tosylimine with indole catalyzed by 0.04 mol% loading of (R)-1-Ni gave the product in 92% isolated yield and 91% ee in DCE at 0 °C after 10 h (Table 2, entry 1). A variety of aryl-substituted aldimines containing electron-donating and electron-withdrawing groups on the aromatic rings were tolerated, affording 89–99% isolated yields with 90–99.7% ee. The highest enantioselectivity was attained with o-methyl-substituted arylimine, affording 89% yield with 99.7% ee. Again, homogeneous controls 1-Ni* and Me4L (0.03 mol% and 0.24 mol% loadings, respectively) exhibited lower enantioselectivities than the HOF 1-Ni, further illustrating the superiority of the polycage catalyst. Several tests also proved the heterogeneous nature of 1-Ni in the above F-C reactions. The heterogeneous catalyst can be recycled and reused for at least 10 runs with negligible loss of efficiency and enantioselectivity as well, and the recovered solid retained crystallinity and porosity and remained structurally intact (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 8).

Considerable efforts have been made on immobilizing chiral phosphoric acids on solid supports such as silica, linear and dendrimer-like polymers and amorphous porous organic polymers for high recyclability despite the fact that the resulting catalysts generally suffer from the disadvantages of uneven catalytic sites and low catalyst loading62,63,64,65,66,67(Supplementary Table 7). With few exceptions63, the examined catalysts typically provide unsatisfactory selectivity. A pair of chiral MOFs has also been prepared based on enantiopure binol-phosphoric acids and investigated as heterogeneous Brønsted acid catalysts for F-C alkylation of indole with imines14, but with much lower activity (20–45% yield) and stereoselectivity (6–44% ee) than the HOF 1-Ni. To the best of our knowledge, the stereoselectivity of 1-Ni exceeded those of reported heterogeneous catalysts for the F-C reactions68 and were comparable even to those of the most enantioselective homogeneous systems based on phosphoric acids reported to date44,61. On the other hand, only few chiral phosphoric acids have been reported to be highly enantioselective homogeneous catalysts for [3+2] coupling of indoles with quinone monoimine and no heterogeneous catalysts have been reported for such coupling reactions. The 3,3′-bis(2,4,6-triisopropylphenyl)-binol phosphoric acid catalyst was shown to afford the best result, with 86–99% ee for the asymmetric [3+2] coupling reactions, which are comparable to the results of the HOF catalyst 1-Ni60. Therefore, high stereoselectivities are noteworthy features of the present 1-Ni-based protocol, which are even among the highest enantioselective values reported for homogeneous organocatalysts41,60,61.

Discussion

We have reported two chiral spinol-based octahedral cages covered with uncoordinated phosphoric and carboxylic acid groups, allowing for cages to self-assemble into permanent porous HOFs through preordered hydrogen bonds. The HOF frameworks possess channels decorated with free chiral phosphoric acid groups can be heterogeneous and recyclable Brønsted acid catalysts to promote [3+2] coupling of indoles with quinone monoimine and F-C alkylations of indole and aryl aldimines with high enantioselectivities (up to 99.9% ee). The HOF catalyst can be recovered and recycled at least ten times without loss of activity and enantioselectivity. This work thus not only provides a new approach to prepare highly enantioselective heterogeneous Brønsted acid catalysts but also lays a solid foundation for the development of novel chiral permanent porous materials from metallocages and metallacycles for enantioslective processes such as enantioselective recognition, sensing and separation, asymmetric catalysis, and chiral optics.

Methods

Synthesis of HOFs 1-Ni and 1-Co

A mixture of NiCl2·6H2O (142.6 mg, 0.6 mmol) or Co(NO3)2·6H2O (174.6 mg, 0.6 mmol), H4TBSC (51 mg, 0.06 mmol), and H4L (47.7 mg, 0.06 mmol) was ultrasonic dissolved in DMF/H2O (10 mL/1 mL). 1.2 mL 0.1 M HCl was added and the mixture was heated at 80 °C for 3 days. Light green crystals of 1-Ni (75.5 mg, 78%) or burgundy crystals of 1-Co (81.4 mg, 84%) were collected, washed with DMF and acetone, and dried in air. FTIR (KBr, cm−1) for 1-Ni: 3440 (m), 2964 (w), 1711 (w), 1606 (s), 1497 (s), 1459 (w), 1400 (s), 1262 (s), 1194 (w), 1136 (w), 1085 (s), 1018 (m), 900 (w), 838 (s), 795 (s), 627 (w), 568 (s), 497 (m). 1-Co: 3429 (m), 2968 (w), 1722 (w), 1612 (s), 1502 (s), 1450 (w), 1436 (s), 1259 (s), 1189 (w), 1140 (w), 1046 (s), 1022 (m), 896 (w), 843 (s), 789 (s), 622 (w), 567 (s), 493 (m). Elemental Analysis for 1-Ni: Calcd for C600 H472 Ni24 O174 P8 S24: C, 55.85; H, 3.66; Found: C, 56.72; H, 3.21. 1-Co: Calcd for C600 H472 Co24 O174 P8 S24: C, 55.76; H, 3.46; Found: C, 56.44; H, 3.38.

Synthesis of HOF 1-Co′

Synthesis of 1-Co′: A mixture of Co(NO3)2·6H2O (174.6 mg, 0.6 mmol), H4TBSC (51 mg, 0.06 mmol), and H4L′ (59.7 mg, 0.06 mmol) was ultrasonic dissolved in 10 mL DMF, 2 mL 0.1 M HCl was added and the mixture was heated at 80 °C for 3 days. Square light red crystals were collected and subjected to X-ray test. FTIR (KBr, cm−1): 3350 (m), 2960 (w), 1654 (w), 1606 (s), 1594 (s), 1467 (m), 1371 (s), 1263 (s), 1201 (w), 1131 (w), 1084 (s), 1018 (m), 906 (w), 838 (s), 797 (s), 624 (w), 564 (s). Elemental Analysis: Calcd for C728 H536 Co24 O178 P8 S24: C, 59.99; H, 3.68; Found: C, 56.52; H, 3.40.

Synthesis of discrete cage 1-Ni*

Hundred milligram fresh HOF 1-Ni were immersed into 1 mL MeOH and 10 μL anhydrous formic acid was added. After ultrasonic treatment for a while (about 5 min), the crystals of HOF 1-Ni were dissolved and gave a clear solution. Then, Et2O were added and the solution turned cloudy immediately. The discret 1-Ni* were collected by centrifugation and dried in air (81 mg). 1-Ni* was characterized by quadrupole-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (Q-TOF-MS), UV-vis, and circular dichroism (CD) spectra etc.

General procedure for asymmetric [3+2] coupling reaction

To a flame-dried Schlenk Pressure Tube was added 1-Ni or 1-Co (0.52 mg, 0.04 μmol), 3-substituted indoles (0.1 mmol) and 0.5 mL anhydrous MeCN, and the mixture was stirred at 0 °C under N2 atmosphere for 30 min. Quinone monoimine (0.15 mmol) in 0.5 mL precooled anhydrous MeCN was then added via syringe. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C until the reaction completed. Chromatography on silica gel (1:2, EA-PE, v/v) afforded the desired products.

General procedure for asymmetric Friedel-Crafts reaction

To a flame-dried Schlenk Pressure Tube was added 1-Ni (0.52 mg, 0.04 μmol), indole (0.3 mmol) and 0.5 mL anhydrous DCE, and the mixture was stirred at 0 °C under N2 atmosphere for 30 min. N-sulfonyl aldimines (0.1 mmol) in 0.5 mL precooled anhydrous DCE was then added via syringe. The mixture was stirred at 0 °C until the reaction completed. Chromatography on silica gel (1:3, PE-EA, v/v) afforded the desired products.

Single-crystal X-ray crystallography

Single-crystal XRD data for 1-Ni and 1-Co were collected on a Bruker SMART Apex II CCD-based X-ray diffractometer with Cu-Kα radiation in the Instrumental Analysis Center of Shanghai Jiao Tong University, China. Single-crystal XRD data for 1-Co′ were collected on Beamline BL17B of National Facility for Protein Science at Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF). The empirical absorption correction was applied by using the SADABS program69. The structures were solved using direct method, and refined by full-matrix least-squares on F2 by the SHELXTL-2014 software package. All non-H atoms were refined anisotropically. DFIX, SADI, FLAT, DANG, EADP, and SIMU restrains were used to obtain reasonable parameters due to the poor quality of crystal data. All the phenyl rings were constrained to ideal six-membered rings. The solvent molecules were highly disordered, and attempts to locate and refine the solvent peaks were unsuccessful. Contributions to scattering due to these solvent molecules were removed using the SQUEEZE routine of PLATON, structures were then refined again using the data generated under OLEX2-1.270. The contents of the solvent region are not represented in the unit cell contents in the crystal data. Crystal data and details of the data collection are given in Supplementary Table 1, while the selected bond distances and angles are presented in Supplementary Tables 2–4.

Data availability

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for the structures reported in this article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers CCDC 1823162, 1823163, and 1880376. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. All other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information, or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Davis, M. E. Ordered porous materials for emerging applications. Nature 417, 813–821 (2002).

Gupta, P. & Paul, S. Solid acids: green alternatives for acid catalysis. Catal. Today 236, 153–170 (2014).

Li, B. et al. Metal–organic framework based upon the synergy of a Brønsted acid framework and Lewis acid centers as a highly efficient heterogeneous catalyst for fixed-bed reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 4243–4248 (2015).

Sabyrov, K., Jiang, J., Yaghi, O. M. & Somorjai, G. A. Hydroisomerization of n-Hexane using acidified metal–organic framework and platinum nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 12382–12385 (2017).

Zhao, P. et al. Entrapped single tungstate site in zeolite for cooperative catalysis of olefin metathesis with Brønsted acid site. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 6661–6667 (2018).

Blaser, H. U. & Federsel, H. J. Asymmetric catalysis on industrial scale: challenges, approaches and solutions. (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2004).

Yoon, M., Srirambalaji, R. & Kim, K. Homochiral metal–organic frameworks for asymmetric heterogeneous catalysis. Chem. Rev. 112, 1196–1231 (2012).

Lun, D. J., Waterhouse, G. I. N. & Telfer, S. G. A general thermolabile protecting group strategy for organocatalytic metal−organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 5806–5809 (2011).

Banerjee, M. et al. Postsynthetic modification switches an achiral framework to catalytically active homochiral metal−organic porous materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 7524–7525 (2009).

Dang, D., Wu, P., He, C., Xie, Z. & Duan, C. Homochiral metal−organic frameworks for heterogeneous asymmetric catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 14321–14323 (2010).

Chen, X. et al. Boosting chemical stability, catalytic activity, and enantioselectivity of metal–organic frameworks for batch and flow reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 13476–13482 (2017).

Ma, L., Falkowski, J. M., Abney, C. & Lin, W. A series of isoreticular chiral metal–organic frameworks as a tunable platform for asymmetric catalysis. Nat. Chem. 2, 838–846 (2010).

Zhang, Z. et al. Two homochiral organocatalytic metal organic materials with nanoscopic channels. Chem. Commun. 49, 7693–7695 (2013).

Zheng, M., Liu, Y., Wang, C., Liu, S. & Lin, W. Cavity-induced enantioselectivity reversal in a chiral metal–organic framework Brønsted acid catalyst. Chem. Sci. 3, 2623–2627 (2012).

Ingleson, M. J. et al. Generation of a solid Brønsted acid site in a chiral framework. Chem. Commun. 11, 1287–1289 (2008).

Evans, O. R., Ngo, H. L. & Lin, W. Chiral porous solids based on lamellar lanthanide phosphonates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 10395–10396 (2001).

Shimizu, G. K. H., Vaidhyanathan, R. & Taylor, J. M. Phosphonate and sulfonate metal organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1430–1449 (2009).

Kim, S. et al. Achieving superprotonic conduction in metal–organic frameworks through iterative design advances. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 1077–1082 (2018).

Bao, Z. et al. Fine tuning and specific binding sites with a porous hydrogen-bonded metal-complex framework for gas selective separations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 4596–4603 (2018).

Nugent, P. S. et al. A robust molecular porous material with high CO2 uptake and selectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 10950–10953 (2013).

Hu, F. et al. An ultrastable and easily regenerated hydrogen-bonded organic molecular framework with permanent porosity. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 56, 2101–2104 (2017).

Hisaki, I. et al. A series of layered assemblies of hydrogen-bonded, hexagonal networks of C 3-symmetric π-conjugated molecules: A potential motif of porous organic materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 6617–6628 (2016).

Yin, Q. et al. An ultra-robust and crystalline redeemable hydrogen-bonded organic framework for synergistic chemo-photodynamic therapy. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 57, 7691–7696 (2018).

Li, P. et al. A homochiral microporous hydrogen-bonded organic framework for highly enantioselective separation of secondary alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 547–549 (2014).

Yang, W. et al. Exceptional thermal stability in a supramolecular organic framework: porosity and gas storage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 14457–14469 (2010).

Lim, S. et al. Cucurbit[6]uril: organic molecular porous material with permanent porosity, exceptional stability, and acetylene sorption properties. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 47, 3352–3355 (2008).

Cook, T. R. & Stang, P. J. Recent developments in the preparation and chemistry of metallacycles and metallacages via coordination. Chem. Rev. 115, 7001–7045 (2015).

Li, J. & Zhou, H. Bridging-ligand-substitution strategy for the preparation of metal–organic polyhedra. Nat. Chem. 2, 893–898 (2010).

Cullen, W., Misuraca, M. C., Hunter, C. A., Williams, N. H. & Ward, M. D. Highly efficient catalysis of the Kemp elimination in the cavity of a cubic coordination cage. Nat. Chem. 8, 231–236 (2016).

Mal, P., Breiner, B., Rissanen, K. & Nitschke, J. R. White phosphorus is air-stable within a self-assembled tetrahedral capsule. Science 324, 1697–1699 (2009).

Li, H., Han, Y., Lin, Y., Guo, Z. & Jin, G. Stepwise construction of discrete heterometallic coordination cages based on self-sorting strategy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 2982–2985 (2014).

Liu, T., Chen, Y., Yakovenko, A. A. & Zhou, H. Interconversion between discrete and a chain of nanocages: self-assembly via a solvent-driven, dimension-augmentation strategy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 17358–17361 (2012).

Niu, Z. et al. Coordination-driven polymerization of supramolecular nanocages. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 14873–14876 (2015).

Zhang, C., Patil, R. S., Liu, C., Barnes, C. L. & Atwood, J. L. Controlled 2D assembly of nickel-seamed hexameric pyrogallol[4]arene nanocapsules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 2920–2923 (2017).

Sava, D. F. et al. Exceptional stability and high hydrogen uptake in hydrogen-bonded metal−organic cubes possessing ACO and AST zeolite-like topologies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 10394–10396 (2009).

Zhai, Q. et al. Cooperative crystallization of heterometallic indium–chromium metal–organic polyhedra and their fast proton conductivity. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 54, 7886–7890 (2015).

Luo, D., Zhou, X. & Li, D. Beyond molecules: mesoporous supramolecular frameworks self-assembled from coordination cages and inorganic anions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 54, 6190–6195 (2015).

Pang, Q., Tu, B., Ning, E., Li, Q. & Zhao, D. Distinct packings of supramolecular building blocks in metal–organic frameworks based on imidazoledicarboxylic acid. Inorg. Chem. 54, 9678–9680 (2015).

Mondal, S. S. et al. Giant Zn14 molecular building block in hydrogen-bonded network with permanent porosity for gas uptake. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 44–47 (2014).

Ju, Z., Liu, G., Chen, Y., Yuan, D. & Chen, B. From coordination cages to a stable crystalline porous hydrogen-bonded framework. Chem. Eur. J. 23, 4774–4777 (2017).

Parmar, D., Sugiono, E., Raja, S. & Rueping, M. Complete field guide to asymmetric BINOL-phosphate derived Brønsted acid and metal catalysis: history and classification by mode of activation; Brønsted acidity, hydrogen bonding, ion pairing, and metal phosphates. Chem. Rev. 114, 9047–9153 (2014).

Xie, J. & Zhou, Q. Magical chiral spiro ligands. Acta Chim. Sin. 72, 778–797 (2014).

Zhou, F. & Yamamoto, H. A powerful chiral phosphoric acid catalyst for enantioselective Mukaiyama–Mannich reactions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 55, 8970–8974 (2016).

Kang, Q., Zhao, Z. & You, S. Highly enantioselective Friedel−Crafts reaction of indoles with imines by a chiral phosphoric acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 1484–1485 (2007).

Huang, D., Xu, F., Lin, X. & Wang, Y. Highly enantioselective Pictet-Spengler reaction catalyzed by SPINOL-phosphoric acids. Chem. Eur. J. 18, 3148–3152 (2012).

He, L. et al. Highly enantioselective Aza-Diels-Alder reaction of 1-azadienes with enecarbamates catalyzed by chiral phosphoric acids. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 52, 11088–11091 (2013).

Dai, F. & Wang, Z. Modular assembly of metal–organic supercontainers incorporating sulfonylcalixarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 8002–8005 (2012).

Wang, S. et al. Ultrafine Pt nanoclusters confined in a calixarene-based {Ni24} coordination cage for high-efficient hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 16236–16239 (2016).

Zhang, J. et al. Highly efficient and practical resolution of 1,1′-spirobiindane-7,7′-diol by inclusion crystallization with N-benzylcinchonidinium chloride. Tetrahedron.: Asymmetry 13, 1363–1366 (2002).

Steiner, T. & Desiraju, G. R. The weak hydrogen bond in structural chemistry and biology 108 (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1999).

Spek, A. Single-crystal structure validation with the program PLATON. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2003, 36, 7 (2003).

Guo, J. et al. Regio-and enantioselective photodimerization within the confined space of a homochiral ruthenium/palladium heterometallic coordination cage. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 56, 3852–3856 (2017).

Little, M. et al. Trapping virtual pores by crystal retro-engineering. Nat. Chem. 7, 153–159 (2015).

Liu, T., Liu, Y., Xuan, W. & Cui, Y. Chiral nanoscale metal-organic tetrahedral cages: diastereoselective self-assembly and enantioselective separation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 49, 4121–4124 (2010).

Xu, D. & Warmuth, R. Edge-directed dynamic covalent synthesis of a chiral nanocube. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 7520–7521 (2008).

Nishioka, Y., Yamaguchi, T., Kawano, M. & Fujita, M. Asymmetric [2+2] olefin cross photoaddition in a self-assembled host with remote chiral auxiliaries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 8160–8161 (2008).

Zhao, C. et al. Chiral amide directed assembly of a diastereo- and enantiopure supramolecular host and its application to enantioselective catalysis of neutral substrates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 18802–18805 (2013).

Liu, Y. et al. Chiral metal–organic frameworks bearing free carboxylic acids for organocatalyst encapsulation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 53, 13821–13825 (2014).

Jiang, J. & Yaghi, O. M. Brønsted acidity in metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Rev. 115, 6966–6997 (2015).

Liao, L. et al. Highly enantioselective [3+2] coupling of indoles with quinone monoimines promoted by a chiral phosphoric acid. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 53, 10471–10475 (2014).

Xing, C., Liao, Y., Ng, J. & Hu, Q. Optically active 1,1′-spirobiindane-7,7′-diol (SPINOL)-based phosphoric acids as highly enantioselective catalysts for asymmetric organocatalysis. J. Org. Chem. 76, 4125–4131 (2011).

Kundu, D. S., Schmidt, J., Bleschke, C., Thomas, A. & Blechert, S. A microporous binol-derived phosphoric acid. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 51, 5456–5459 (2012).

Rueping, M., Sugiono, E., Steck, A. & Theissmann, T. Synthesis and application of polymer-supported chiral Brønsted acid organocatalysts. Adv. Synth. Catal. 352, 281–287 (2010).

Bleschke, C., Schmidt, J., Kundu, D. S., Blechert, S. & Thomas, A. A chiral microporous polymer network as asymmetric heterogeneous organocatalyst. Adv. Synth. Catal. 353, 3101–3106 (2011).

Schmidt, J., Kundu, D. S., Blechert, S. & Thomas, A. Tuning porosity and activity of microporous polymer network organocatalysts by co-polymerisation. Chem. Commun. 50, 3347–3349 (2014).

Almenara, L. C., Escrich, C. R., Planes, L. O. & Pericàs, M. A. Polystyrene-supported TRIP: a highly recyclable catalyst for batch and flow enantioselective allylation of aldehydes. ACS Catal. 6, 7647–7651 (2016).

Zhang, X., Kormos, A. & Zhang, J. Self-supported BINOL-derived phosphoric acid based on a chiral carbazolic porous framework. Org. Lett. 19, 6072–6075 (2017).

Yu, P., He, J. & Guo, C. 9-Thiourea Cinchona alkaloid supported on mesoporous silica as a highly enantioselective, recyclable heterogeneous asymmetric catalyst. Chem. Commun. 39, 2355–2357 (2008).

G. M. Sheldrick. SADABS, Program for Empirical Absorption Correction of Area Detector Data. (University of Götingen, Götingen, Germany, 1996).

Dolomanov, O. V., Bourhis, L. J., Gildea, R. J., Howard, J. A. K., Puschmann, H. OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 42, 339–341 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge many helpful discussions with Professor Qilin Zhou and Jianhua Xie (Nankai University, China). This work was financially supported by the National Science Foundation of China (Grants 21522104, 21431004, 21620102001, 21875136, and 91856204), the National Key Basic Research Program of China (Grants 2014CB932102 and 2016YFA 0203400), Key Project of Basic Research of Shanghai (17JC1403100 and 18JC1413200), and the Shanghai “Eastern Scholar” Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Y. conceived and designed the research. G.W., C.D., J.H., and C.X. performed the experiments. C.Y., L.Y., and G.W. analyzed the data and co-wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gong, W., Chu, D., Jiang, H. et al. Permanent porous hydrogen-bonded frameworks with two types of Brønsted acid sites for heterogeneous asymmetric catalysis. Nat Commun 10, 600 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08416-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-08416-6

This article is cited by

-

Supramolecular polynuclear clusters sustained cubic hydrogen bonded frameworks with octahedral cages for reversible photochromism

Nature Communications (2024)

-

Topochemical polymerization of hydrogen-bonded organic framework for supporting ultrafine palladium nanoparticles

Science China Chemistry (2023)

-

Hydrogen-bonded organic framework for red light-mediated photocatalysis

Nano Research (2023)

-

Sulfonylcalix[4]arene-based metal-organic polyhedra with hierarchical porous structures for efficient Xe/Kr separation

Nano Research (2023)

-

Single-crystal structure of two-dimensional organic framework based on donor-acceptor interactions with charge-transfer effect

Science China Chemistry (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.