Abstract

Extended-coordination sphere interactions between dissolved metals and other ions, including electrolyte cations, are not known to perturb the electrochemical behavior of metal cations in water. Herein, we report the stabilization of higher-oxidation-state Np dioxocations in aqueous chloride solutions by hydrophobic tetra-n-alkylammonium (TAA+) cations—an effect not exerted by fully hydrated Li+ cations under similar conditions. Experimental and molecular dynamics simulation results indicate that TAA+ cations not only drive enhanced coordination of anionic Cl– ligands to NpV/VI but also associate with the resulting Np complexes via non-covalent interactions, which together decrease the electrode potential of the NpVI/NpV couple by up to 220 mV (ΔΔG = −22.2 kJ mol−1). Understanding the solvation-dependent interplay between electrolyte cations and metal–oxo species opens an avenue for controlling the formation and redox properties of metal complexes in solution. It also provides valuable mechanistic insights into actinide separation processes that widely use quaternary ammonium cations as extractants or in room temperature ionic liquids.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The electrochemical behavior of redox-active metal cations is inherently dependent on the inner-sphere coordination environment surrounding the metal center1,2. Although this fundamental principle holds true, there is increasing evidence that the chemical environment beyond the first coordination sphere can also influence the observed electrochemical properties3,4,5,6,7. For example, by measuring electrode potentials in organic media and by characterizing solid reaction products, several recent studies have demonstrated that direct second-sphere coordination of strong Lewis acids to oxo groups enhances the redox activity of metal–oxo complexes, including increasing the oxidizing capacity of manganese–oxo clusters in the oxygen-evolving complex of photosystem II5,6 and facilitating oxo group functionalization and reduction of the uranyl ion, UO22+ 3,4. For aqueous systems, however, the hydration of charged species (e.g., ion–solvent interactions) is expected to inhibit or outcompete any direct ion–ion interactions between molecular metal complexes and other cations8, such that the influence of extended-coordination environments on the redox chemistry of metals dissolved in water has been overlooked.

To address this knowledge gap, we examined the redox behavior of NpV in acidic aqueous chloride solutions as a function of electrolyte cation. The chemical properties of NpV make it an excellent choice for studying the influence of extended-coordination environments on the redox chemistry of aqueous metal ions. First, in aqueous solutions, high-valent early actinides exist as dioxo actinyl cations (AnVO2+ or AnVIO22+, where An = U, Np, Pu, and Am), which have a unique and stable nearly linear structure, with two strong An–O covalent bonds9. The partial negative character on the yl (yl = actinyl) oxygen atoms facilitates interactions with other cations10,11, including other actinyl cations12,13,14,15,16, which is generally termed cation–cation interaction (CCI)12. This property, namely the reactivity of the actinyl oxo group, provides a chemical path for defined second-coordination sphere interactions that do not perturb the inner-coordination sphere (the actinyl unit). Compared to AnVIO22+ complexes, the lower nuclear charge of the AnV increases the Lewis basicity of the yl–oxo in AnVO2+ complexes, enhancing extended-coordination sphere interactions for AnV cations17. Additionally, of the AnVO2+ species, NpVO2+ is the most thermodynamically stable18. Second, unlike transition-metal–oxo complexes that readily undergo hydrolysis and oligomerization, of which the latter can compete with second-coordination sphere bonding, hydrolysis and oligomerization of NpVO2+ are unlikely under mildly acidic conditions19. In fact, previous studies, including EXAFS, indicate that NpV speciation in acidic chloride solutions (pH = 2, [Cl–] ≤ 6 M) is dominated by a simple monomeric pentahydrate complex, [NpVO2(H2O)5]+ 20. Third, in aqueous solutions, the NpVI/NpV redox couple is easily accessible (E° = +0.959(4) V vs. Ag/AgCl)18 and generally exhibits reversible or quasi-reversible electron-transfer properties21,22, permitting a quantitative or semiquantitative evaluation of the NpVI/NpV electron-transfer thermodynamics.

In the present work, we combine electroanalytical chemistry, vibrational and electronic spectroscopies, X-ray crystallography, and molecular dynamics simulations to characterize the interactions that electrolyte cations (A+ = Li+ or tetra-n-alkylammonium cations (TAA+ = [NMe4]+, [NEt4]+)) have with NpVO2+ cations in aqueous systems, and to understand the effect these interactions have on NpV redox behavior, both in solution and during solution evaporation and crystal formation. The two electrolyte cations, Li+ and TAA+, which are widely used as non-reacting, charge-balancing ions, have significantly different ionic radii and hydration and H-bonding properties, allowing us to investigate how these properties influence interactions between the electrolyte and neptunyl cations in aqueous solution. Here, we show that hydrophobic TAA+ cations unexpectedly stabilize higher-oxidation-state metal–oxo cations dissolved in aqueous solutions, whereas the strong Lewis acid, Li+, has no effect on the observed redox behavior. Furthermore, we show that TAA+ cations, which are not Lewis acids, influence the redox behavior of metal–oxo cations via non-covalent ion association with the metal–oxo complex, not via direct bonding with the oxo group. These findings highlight the underappreciated influence of electrolyte cations on the redox chemistry of metal cations and underscore the important role that ion–solvent interactions play in governing extended-coordination sphere interactions between metal cations and other ions in solution.

Results

Redox chemistry of NpV in LiCl and NMe4Cl solutions

We first probed the redox chemistry of NpV in several acidic aqueous chloride solutions as a function of A+ using cyclic voltammetry (CV). In 1 M and 5 M LiCl (pH ≈ 1.3), the oxidation of NpV is quasi-reversible (i.e., controlled by both charge transfer and mass transport), with average half-wave potentials (E1/2) of +0.924(2) V and +0.929(3) V vs. Ag/AgCl, respectively (Supplementary Discussion, Supplementary Figure 2, and Supplementary Table 1). These electrode potentials are equal (within error), indicating that increases in LiCl concentration and ionic strength do not affect the redox behavior of NpV (Supplementary Figure 3). Furthermore, the electrode potentials measured here for the LiCl solutions agree well with the electrode potentials previously reported for the NpVI/NpV couple in 1 M HClO421 (Supplementary Table 1). Taken together, these data indicate that the underlying electronic structure and chemical environment of NpV in solutions of 1 or 5 M LiCl and 1 M HClO4 are the same, and that NpV remains present predominantly as the free, hydrated cation, [NpO2(H2O)5]+, as expected from previous studies20,23.

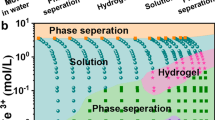

In contrast, when Li+ cations in solution are replaced by TAA+ cations, the measured NpVI/NpV electrode potential decreases substantially, by as much as 220 mV, indicating that the presence of TAA+ cations in solution increases the thermodynamic stability of NpVI relative to NpV (Fig. 1). Specifically, in 1 M, 3 M, and 5 M NMe4Cl (pH ≈ 1.3), CV data indicate that electron transfer for the NpVI/NpV redox couple is quasi-reversible, with average E1/2 values of +0.903(4) V, +0.818(7) V, and +0.704(7) V vs. Ag/AgCl, respectively (Supplementary Discussion, Supplementary Figure 4, and Supplementary Table 1). Noting that only the electrolyte cation was changed in these experiments, the large cathodic shifts of the NpVI/NpV electrode potential are unexpected, particularly considering that Cl– is a weak ligand24. Similar magnitude cathodic shifts of the AnVI/AnV electrode potential in aqueous systems have only been observed in the presence of strong coordinating ligands, such as sulfate25, carbonate26, or hydroxide27. Moreover, the gradual linear decrease of the electrode potential with increasing NMe4Cl concentrations provides clear evidence for the formation of one or more additional NpV species28, which exhibit greater thermodynamic stabilization toward NpVI and which are in equilibrium with existing [NpO2(H2O)5]+ complexes. The NpVI/NpV electrode potentials measured in mixed constant-ionic-strength LiCl/NMe4Cl solutions and in NEt4Cl are similar in magnitude to the electrode potentials measured in NMe4Cl solutions with the same TAA+ concentration (Supplementary Discussion, Supplementary Figure 5, and Supplementary Table 1), confirming that the shifts of the NpVI/NpV electrode potentials are not due to increasing ionic strength and are not specific to solutions containing [NMe4]+ cations.

Effect of Li+ vs. [NMe4]+ on the NpVI/NpV couple. Current-normalized cyclic voltammetry data for solutions of 5 mM NpV dissolved in 5 M NMe4Cl or 5 M LiCl at pH ≈ 1.3. The arrow indicates the initial scan direction. Initial and cathodic switching potential = 400/550 mV; anodic switching potential = 1000/1150 mV; ν = 100 mV s−1

Raman and Vis–NIR absorption spectroscopy

Raman spectra confirm the hypothesis that additional NpVO2+ species form in the TAACl solutions, as illustrated by the spectra for NpV solutions in which LiCl was gradually replaced with NEt4Cl (Fig. 2). For this experiment, NEt4Cl was substituted for NMe4Cl to avoid spectral interference from the [NMe4]+ cation (ν1 ≈ 759 cm−1). In solutions of 3.5 M LiCl, the Raman spectrum of NpV exhibits the characteristic NpVO2+ ν1 band at 767 cm−1, which originates from symmetric stretching of the O=NpV=O unit of the hydrated cation, [NpO2(H2O)5]+ (Fig. 2)29. With increasing NEt4Cl concentrations, the Raman spectra reveal the ingrowth of a vibrational band at ≈736 cm−1 (Fig. 2). This band occurs as a low-frequency shoulder on the NpVO2+ ν1 band, indicating that the presence of TAA+ cations induces the formation of NpV species with weaker Np–Oyl bonding.

Comparison of NpV Raman spectra. Raman spectra of 0.12 M NpV dissolved in 3.5 M LiCl (Np/Li, black line), 1.75 M LiCl/1.75 M NEt4Cl (Np/Li/NEt4, magenta line), and 3.5 M NEt4Cl (Np/NEt4, blue line); Raman spectra of a 3.5 M NEt4Cl solution (green line) and of the crystalline product [NMe4]Cl[NpO2Cl(H2O)4] (3) (orange line). The intensities of all spectra are scaled to facilitate comparison

There are two known mechanisms that could cause a red shift of the actinyl ν1 vibrational band. First, weakening of the NpV–Oyl bond could be due to the inner-sphere coordination of electron-donating chloride ligands in the NpV equatorial plane24,30,31. Alternatively, the formation of [O=NpV=O···Mn+] complexes (Mn+ = highly charged metal cation) could also weaken the Np–Oyl bond and decrease the ν1 frequency, as previously observed in dimeric NpV CCI complexes32.

However, in contrast to the spectra of known aqueous [NpVO2Cln(H2O)m](n–1) or [O=NpV=O···Mn+] complexes11,15,23, the Vis–NIR absorption spectra of the NpV–TAACl solutions (Supplementary Figure 6) do not show the ingrowth of peaks at wavelengths higher than the characteristic NpV 5f → 5f transition at 980.2 nm33, suggesting that the interactions between NpVO2+ cations and other constituents in the TAACl solutions, which include Cl− and TAA+ ions and H2O molecules, deviate from any interactions previously reported. Instead, the absorption spectra for 5 mM NpV dissolved in 1, 3, and 5 M NMe4Cl solutions exhibit a small, but significant (up to 2 nm) gradual blue shift of the 980.2 nm band (Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary Figure 6). No noticeable shift of the 980.2 nm band was observed in the absorption spectra for the 5 M LiCl solutions. These results are consistent with findings from the electroanalytical experiments, confirming a negligible impact of LiCl on NpV chemistry in solution.

Syntheses and structures of representative Np compounds

How do NpVO2+ cations interact with other solution constituents, particularly TAA+ cations, and how do these interactions stabilize higher-oxidation-state neptunyl species? To answer these questions, we crystallized potential neptunyl solution species by evaporation of acidic chloride solutions containing either Li+ or TAA+ cations. Subsequently, the solid products were characterized using single-crystal X-ray diffraction and Raman spectroscopy. The evaporation experiments reported here were conducted under conditions comparable to previously reported reactions containing only NpVO2+ and HCl16,34, for which open-air evaporation yields a range of products, including the CCI compound, (NpVO2)Cl(H2O)2, a mixed-valent NpIV/V compound, and other unidentified green phases16,34.

The open-air evaporation of NpV/HCl solutions containing Li+ yields similar products, confirming that Li+ does not influence the redox behavior of NpV or the formation of CCI complexes in solution. All of the green products that form from the evaporation of NpV/Li/HCl solutions, including the compound, (NpO2)4Cl4(H2O)7 (1), have Raman signatures matching those of products from Li-free NpV/HCl reactions (Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary Figure 13). Although the disproportionation of NpV to NpIV and NpVI is also possible during evaporative syntheses from acidic solutions, no evidence for the formation of NpVI compounds was observed. The structure of 1 is closely related to that of the dihydrate, (NpVO2)Cl(H2O)216, both of which adopt a 3-D CCI network of squarely arranged NpVO2+ cations with open channels filled by Cl– anions and H2O molecules (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Discussion, Supplementary Figure 9, and Supplementary Figure 10). With a pentagonal bipyramidal geometry, each NpVO2+ cation in the dihydrate and in 1 is coordinated by five ligands in the equatorial plane, which include two yl–O atoms, zero to three H2O molecules, and zero to three Cl– anions (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Figure 9). The Np–Oyl distances (Supplementary Table 3) and ν1 stretching frequencies for the dihydrate and 1 are also comparable at approximately 1.845 Å and 672 cm–1 (Supplementary Discussion).

Structure of (NpO2)4Cl4(H2O)7 (1). a Projection of the three-dimensional network of cation−cation-bonded NpVO2+ square nets, with open channels along the [0 0 1] direction. Chloride anions and water molecules that reside inside the channels are omitted for clarity. b Local coordination environments and connectivities of four crystallographically unique NpVO2+ cations in the structure of 1. Half of the disordered Cl and Ow positions are omitted for clarity. Green, red, pink, and orange spheres represent Np, Oyl (yl = actinyl), Ow (w = water), and Cl atoms, respectively

In contrast, during solution evaporation in open air, the presence of [NMe4]+ in the NpV/HCl solutions drastically alters neptunium’s coordination and redox chemistry. Unlike the solid products that formed during the evaporation of solutions containing Li+, no NpV CCI and no NpIV compounds formed during the evaporation of solutions containing [NMe4]+. Instead, yellow–green crystals of [NMe4]2[NpVIO2Cl4] (2) form readily upon solution evaporation in air, indicating that the presence of [NMe4]+ cations inhibits the formation of CCI compounds and promotes NpV oxidation to NpVI. This finding is consistent with our voltammetry data that clearly demonstrate enhanced stabilization of NpVI relative to NpV in the presence of [NMe4]+ cations.

The structure of compound 2, which consists of molecular [NpVIO2Cl4]2− complexes and [NMe4]+ cations (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Discussion, and Supplementary Figure 11), also provides a possible model for the interplay between oxidized Np cations and other solution constituents in the electrochemical experiments (Fig. 4a). In fact, the NpVIO22+ unit in the structure of 2 appears to be strongly perturbed by its surrounding environment, which includes Cl− and [NMe4]+ ions. More specifically, Np−Oyl distances within the tetragonal bipyramidal [NpVIO2Cl4]2− units in 2 are 1.765(3) Å, which are much longer than those for [NpVIO2(H2O)5]2+ complexes in the structure of [NpO2(H2O)5](ClO4)2 (1.7479(9) and 1.740(1) Å)35. The ν1 symmetric stretching band for O=NpVI=O moieties in 2 occurs at 797 cm−1 (Supplementary Figure 13), which is approximately 60 cm−1 less than that for free [NpVIO2(H2O)5]2+ complexes in solution (855 cm−1). This finding confirms weakening of the NpVI–Oyl bond in 2, which has been attributed to the coordination of four chloride (electron-donating) ligands in the NpVIO22+ equatorial plane in similar compounds. Additional non-covalent interactions between yl–O atoms and [NMe4]+ cations and between coordinated Cl– anions and [NMe4]+ cations are apparent, which may also affect the electronic structure of the NpVIO22+ cations in 2. In total, each discrete [NpVIO2Cl4]2− anion attracts eight neighboring [NMe4]+ cations through electrostatic interactions with Oyl and Cl− moieties with Oyl−N and Cl−N distances of 4.5417(9) Å and 4.3377(2)–4.5617(3) Å (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Discussion, and Supplementary Table 4). Additionally, each Oyl and Cl atom potentially participates in four H-bonds with the methyl group of four neighboring [NMe4]+ cations, with donor–acceptor distances ranging from 3.385(3) Å (C−H⋅⋅⋅Oyl) to 3.686(2)–3.901(3) Å (C−H⋅⋅⋅Cl).

Structures of NpVI– and NpV–[NMe4] chlorides. a Local connectivities between one crystallographically unique NpVIO22+ cation, one Cl− anion, and one [NMe4]+ cation in the structure of [NMe4]2[NpO2Cl4] (2). b Local connectivities between one crystallographically unique NpVO2+ cation, two Cl− anions, four water molecules, and one [NMe4]+ cation in the structure of [NMe4]Cl[NpO2Cl(H2O)4] (3). Green, red, pink, orange, blue, black, and beige spheres represent Np, Oyl, Ow, Cl, N, C, and H atoms, respectively. H-bonding is omitted for clarity

To isolate potential NpV species present in TAACl solutions, we repeated the above evaporation experiment in the absence of air to exclude the potential oxidizer, O2. As a result, only teal crystals of [NMe4]Cl[NpVO2Cl(H2O)4] (3) were obtained. In addition to discrete [NMe4]+ and Cl– ions, compound 3 contains molecular actinyl monochloride complexes, [NpVO2Cl(H2O)4], which confirms the existence of NpV–monochloro species in TAACl solutions (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Discussion, and Supplementary Figure 12). No other Np chemistry (i.e., formation of CCI or NpIV compounds) was observed during this evaporation experiment, confirming that [NMe4]+ cations inhibit the formation of Np CCI complexes and suggesting that O2 is the oxidant responsible for the NpV oxidation observed during the evaporation of NMe4Cl solutions in open air.

In addition, the structure of 3 provides crucial evidence supporting the substantial impact of neptunium-extended coordination environments on NpV–Oyl bonding. This is evidenced by the elongated NpV–Oyl distances (1.838(2) and 1.843(2) Å) and the red-shifted symmetric stretching frequency (ν1 = 741 cm−1) in 3 (Fig. 2), compared with the distances and symmetric stretching frequencies observed in other non-CCI compounds, such as Na3(NpVO2)(SeO4)2(H2O) (Np–Oyl = 1.813(3) Å and 1.831(3) Å; ν1 = 773 cm−1)36. Considering the weaker donating capacity of Cl− anions compared with oxoanions24,30, such as selenate, the weakened Np–Oyl bonding in 3 results from the non-covalent interactions between NpVO2+ cations and [NMe4]+ cations and H2O ligands. Each [NpO2Cl(H2O)4] complex in the structure of 3 bonds to five [NMe4]+ cations through Oyl/Cl(2)–⋅⋅⋅[NMe4]+ electrostatic interactions and through potential H-bonds between Cl(2) atoms and methyl groups (Supplementary Discussion and Supplementary Table 5). More specifically, each yl–O atom attracts one [NMe4]+ cation with Oyl−N distances of 4.062(3) or 4.660(3) Å and each Cl(2)− anion attracts four [NMe4]+ cations with Cl−N distances in the range of 4.184(2)−5.156(2) Å. In addition, each yl–O atom participates in two H-bonds with the H2O ligands from surrounding [NpO2Cl(H2O)4] complexes, with Ow−H⋅⋅⋅Oyl distances of 2.733(3)−2.859(3) Å. Interestingly, the neptunyl ν1 band for the pentagonal bipyramidal [NpVO2Cl(H2O)4] complexes in 3 matches the frequency of the shoulder peak observed in the Raman spectrum of the 0.12 M NpV/3.5 M NEt4Cl solution (Fig. 2). This finding indicates that the NpV/NEt4Cl solution contains NpVO2+ species that have similar structural properties and that participate in similar non-covalent interactions as the NpVO2+ species in 3.

Molecular dynamics simulations

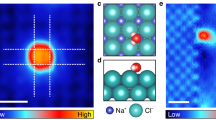

The non-covalent extended-sphere interactions between NpV and TAA+ cations and the influence of these interactions on the first coordination sphere of NpV are further supported by all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. All MD simulations were performed on 0.1 M NpV or NpVI solutions at pH = 2 in the presence of 5 M LiCl or 5 M NMe4Cl (Supplementary Tables 6 and 7, and Supplementary Figures 14, 15, and 16). Consistent with our experimental results, the MD simulations confirm that neptunyl species in 5 M LiCl solutions are dominated by hydrated neptunyl complexes, with only weak Np–Cl coordination (Table 1). Surrounding these neptunyl hydrates, there are only 0.3 and 0.5 Li+ cations, on average, indicating roughly negligible interactions between the neptunyl and Li+ cations. In contrast, both NpV and NpVI exhibit enhanced chloride ligation in the presence of 5 M NMe4Cl. Specifically, substantial quantities of neptunylV mono- and dichlorides and neptunylVI di- and trichlorides formed under the tested conditions (Table 1). These neptunyl–chloride complexes are embedded inside a cage of six (average) [NMe4]+ cations, each of which is located at approximately 6 Å from the Np centers, indicating significant non-covalent interactions between the [NMe4]+ electrolyte cations and the Np first-coordination sphere. These arrangements are comparable to those observed in the structures of 3 and 2 (Fig. 4), where each neptunyl–chloride complex bonds five or eight [NMe4]+ cations via electrostatic and potential H-bonding interactions with the yl–O atoms or Cl− anions, with Np–N distances of 5.292(4)–7.424(2) Å and 5.3745(3) Å for NpV and NpVI, respectively.

Discussion

On the basis of the experimental and simulation results, we propose that TAA+ cations promote the formation of inner-sphere NpV–chloride complexes in solution. The formation of such complexes is expected to decrease the measured NpVI/NpV electrode potential because NpVIO22+ cations form stronger complexes with electron-donating chloride ligands than NpVO2+ cations19,23. Our combined data, particularly the crystallization of [NMe4]Cl[NpVO2Cl(H2O)4] (3) and the enhanced neptunyl–chloride complexation observed in the MD simulations for NMe4Cl solutions, suggest that monochloro–NpV complexes coexist with [NpO2(H2O)5]+ complexes in TAACl solutions. However, existing thermodynamic data reveal that the free energy difference expected as a result of the formation of monochloro–neptunyl complexes (ΔΔG = −3.94 kJ mol−1, Supplementary Table 8) is inadequate to account for the large thermodynamic stabilization of NpVI observed in 5 M NMe4Cl (ΔE1/2 ≈ −220 mV → ΔΔG = –22.2 kJ mol−1, Supplementary Table 8). The formation of higher-order neptunyl–chloride complexes in solution is also possible, as indicated by the structure of 2 and the MD results, and may further decrease the NpVI/NpV electrode potential37. The corresponding thermodynamic data for higher-order neptunyl–chloride complexes are unknown, but a decrease of the NpVI/NpV electrode potential less than 220 mV would be expected, considering the weak electron-donating capability of the chloride ligand24,30.

In addition to the NpVI stabilization conferred upon chloride complexation, the extended-sphere association with TAA+ cations, forming [NpVO2Cln(H2O)m](1–n)•••TAAx+ groups, further decreases the NpVI/NpV electrode potential. For homogeneous 2 and 5 M NMe4Cl solutions, the calculated separation between the centers of [NMe4]+ and Cl− ions is about 7.5 and 5.5 Å, which are close to the N−Cl distances for solvent-separated (7.5Å) and contact (5.0 Å) [NMe4]+−Cl− ion pairs in aqueous solution38. As a result, interactions between TAA+ cations and free Cl− anions and between TAA+ cations and the Cl− anions of [NpVO2Cln(H2O)m](1−n) complexes are expected under the solution conditions employed herein. Considering the structure of 3 (Fig. 4) and the MD results (Supplementary Figure 16), we also expect electrostatic and potential H-bonding interactions between TAA+ cations and yl–O atoms in solution. As a whole, it appears that yl–O atoms and coordinated Cl− ligands are both key players mediating the association of neptunyl and TAA+ cations. To separate the synergetic effect of yl–O atoms and Cl− ligands, similar experiments with the non-complexing ClO4– ligand were planned but could not be executed because of the much lower aqueous solubility of TAAClO4 compared with TAACl salts.

As a final note, we must also consider the chemical and structural properties of water itself, and the important role that water plays in influencing the electrochemical stabilities of neptunyl complexes. As indicated in the structure of 3 and other reported evidence in the literature37,39, water can act as a H-bond donor to the yl–O atoms, particularly those of NpVO2+, in a manner competing with TAA+ cations. With increasing concentrations of TAACl, the concentration of water decreases. This effectively decreases the H-bonding interactions between water molecules and neptunyl cations and decreases the relative permittivity of the solutions (Table 1), facilitating stronger interactions between neptunyl cations and Cl− and TAA+ ions.

The divergence in the reactivity of Li+ and TAA+ cations toward the neptunyl first-coordination sphere in aqueous solutions demonstrated in this study can be attributed to the different solvation properties of the electrolyte cations. In aqueous solutions, Li+ cations are strongly hydrated (ΔHhydration = −530 kJ mol−1)40, such that their charge is effectively shielded from the neptunyl–O atoms and Cl− ions. However, TAA+ cations, which are only weakly hydrated in solution (ΔHhydration ≈ −200 kJ mol−1)40, are expected to more actively engage with the neptunyl–O atoms and Cl− ions via electrostatic interactions. Additionally, potential H-bonding via the alkyl groups may further enhance the association of TAA+ cations and neptunyl complexes in solution. Therefore, despite their lower charge density, compared with Li+ cations, TAA+ cations are expected to associate with NpVO2+ cations in aqueous solutions. These phenomena are well illustrated by the structures of 2 and 3 and by the MD simulation results. The observed differences in neptunyl chemistry in LiCl vs. TAACl solutions are consistent with our recent findings that demonstrate a correlation between countercation (A+ = Li+, Na+, K+, Rb+, Cs+, NH4+, or NR4+ (R = Me, Et, and Bu)) hydration enthalpies and the formation of redox-inactive Th–nitrato molecular complexes from aqueous solution, wherein hydrophobic countercations (e.g., TAA+ cations) tend to associate with more anionic Th−nitrato molecular complexes via stronger non-covalent interactions in solid structures41.

These results highlight the importance of ion hydration properties in regulating the interactions between oxocations and electrolyte cations in solution. The competition between ion solvation and ion association has been well documented for oppositely charged ions such as A+ (A = alkali metal and tetra-n-alkylammonium) and Cl−8. Weak ion–solvent interactions also appear to be essential for ion association between neptunyl species and TAA+ cations in aqueous solutions. Related phenomena have been reported for other oxocation and metal ion systems, supporting the fundamental importance of these underlying chemical principles. For example, stronger interactions between NpVO2+ and highly charged metal cations, such as Al3+ and Fe3+, are observed in mixed aqueous polar–organic solvents than in aqueous media because ion–solvation interactions are weaker in the mixed solvents42. Other metal–oxo complexes with similar extended coordination environments, such as those of iron–43, manganese–5,6, and uranium–oxocations3,4, have been isolated in organic solvents, where weak ion–solvent interactions are negligible compared to the strong bonding between oxo groups and extended-sphere metal cations.

The influence of hydrophobic, low-charge density TAA+ cations on the electrochemical properties of neptunyl species in aqueous chloride media arises from a mechanism different than that reported previously for studies involving strong Lewis acids, which have a comparatively higher charge density. These previous studies suggest that direct bonding between Lewis acids, such as Ca2+ or Y3+, and oxo groups tends to increase the electrode potentials of oxocations as a function of increasing Lewis acidity6. In contrast, TAA+ cations associate with neptunyl cations via non-covalent interactions with both the neptunyl oxo groups and equatorial ligands. This association influences ligation within the metal cation’s first coordination sphere, driving enhanced coordination of anionic Cl− ligands to the NpV/VI centers. The sum of all these interactions, namely the inner-sphere coordination with Cl– anions and the outer-sphere association with TAA+ cations, causes a significant decrease of the NpVI/NpV electrode potential to favor NpVI.

Overall, this work opens an avenue of using non-innocent electrolyte cations to control the redox properties and the first-coordination-sphere ligation of metal cations. Furthermore, we highlight that the observed influence of TAA+ cations on the coordination and redox chemistry of neptunyl cations is important in actinide separation processes in which quaternary ammonium cations (e.g., TAA+) are widely employed as anion exchange extractants or in room-temperature ionic liquids (RTILs)44,45,46. In fact, higher-order (anionic) actinide complexes, including chloride complexes, which would not usually be considered dominant aqueous species based on solution ligand concentrations, are preferentially associated with quaternary ammonium cations in these processes45. This study provides significant insight into the underlying principles regarding the interactions between actinide species and quaternary ammonium cations, which will aid in optimizing actinide separation processes and tuning the properties of RTILs.

Methods

Caution!

237Np is an α- and γ-emitting radioisotope and is considered a health risk. Its use requires appropriate infrastructure and personnel trained in the handling of radioactive materials.

Stock solution preparation

Solutions of NpV in 1M HClO4 were purified using a cation-exchange column containing Dowex-50-X8 resin. After purification, Np was precipitated using NaOH, washed with water, and redissolved in 1M HCl. The procedure was used to prepare two separate stock solutions, one for solid-product syntheses and Raman spectroscopy and one for electrochemistry experiments. Identification of the characteristic near-infrared absorption band for NpV at ≈980 nm, and the absence of absorption bands characteristic for other Np oxidation states, confirmed that both Np/HCl stock solutions contained only NpV (Supplementary Figure 1)47. The final purified stock solutions contained 0.24 M or 0.1 M NpV, as determined using liquid scintillation counting (LSC). LiCl (Fisher, >99.0%), NMe4Cl (Acros Organics, >98%), and NEt4Cl (Sigma, >98%) were used as obtained. ACl (A = Li+, [NMe4]+, and [NEt4]+) stock solutions of varying concentrations were prepared by dissolving ACl in deionized H2O.

Voltammetry

Cyclic and differential pulse voltammetry (CV, DPV) data for 5 mM NpV solutions in various static electrolytes were collected at room temperature in the absence of oxygen using a BAS 100B electrochemical workstation, a graphite working electrode, a graphite auxiliary electrode, and a Ag/AgCl (3 M NaCl) reference electrode, which has a redox potential of +0.200 V vs. SHE at 25 °C. All Np solutions used for the electrochemical experiments were prepared individually by mixing an aliquot of the 0.1M NpV stock solution with appropriate volumes of ACl stock solutions and H2O to yield the solutions listed in Supplementary Table 1. The NpV concentrations of select sample solutions were verified using LSC.

Visible–near-infrared (Vis–NIR) absorption spectroscopy

Vis–NIR spectra (400–1300 nm) were collected for diluted NpV stock solutions in standard 1 cm path-length polystyrene cuvettes (Fisher) and for select 5 mM NpV electrochemistry solutions in 0.2 cm path-length micro-volume polystyrene cuvettes (Eppendorf, UVette) using an Olis-modernized Cary 14 spectrophotometer.

Synthesis of (NpO2)4Cl4(H2O)7 (1)

A 25 μL aliquot of the 0.24 M NpV stock solution (in ≈1 M HCl) and 6 μL of a 1 M LiCl solution were combined in a 2 mL glass vial and covered by parafilm with small pin holes. The solutions were left in a vented hood and allowed to slowly evaporate over three months to complete dryness. Solid products included green crystals of 1, a green amorphous solid, and colorless salts (Supplementary Figure 7a).

Syntheses of [NMe4]2[NpO2Cl4] (2) and [NMe4]Cl[NpO2Cl(H2O)4] (3)

A 10 μL aliquot of the 0.24 M NpV stock solution and 5 μL of a 1 M NMe4Cl solution were combined in a 2 mL glass vial and covered by parafilm with small pin holes. The solutions were left in a vented hood and allowed to slowly evaporate to complete dryness. Solid products included up to millimeter-sized yellow–green crystals of 2 and colorless salts (Supplementary Figure 7b). Slowly evaporating the same solution in an apparatus excluding air resulted in teal crystals of 3 and colorless salts (Supplementary Figure 7c).

Structure determinations

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction data for (NpO2)4Cl4(H2O)7 (1), [NMe4]2[NpO2Cl4] (2), and [NMe4]Cl[NpO2Cl(H2O)4] (3) were collected with the use of graphite-monochromatized MoKα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å) at 100 K on a Bruker APEXII diffractometer. The crystal-to-detector distance was 5.00 cm. Data were collected by a scan of 0.3° in ω in groups of 600 frames at φ settings of 0°, 90°, 180°, and 270°. The exposure time was 25 s/frame, 15 s/frame, and 20 s/frame for 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The collection of intensity data as well as cell refinement and data reduction were carried out with the use of the program APEX248. Absorption corrections as well as incident beam and decay corrections were performed with the use of the program SADABS48. The structures were solved with the direct-methods program SHELXS and refined with the least-squares program SHELXL49. Further information is provided in the Supplementary Methods, with select crystallographic data listed in Supplementary Table 2.

Raman spectroscopy

Raman spectra of Np containing solid samples and solutions were collected on a Renishaw inVia Raman Microscope with a circularly polarized excitation line of 532 nm. Due to the radiological hazards associated with 237Np, each solid sample or 2 μL solution sample was placed on a glass drop slide covered with a transparent coverslip, which was sealed to the slide using epoxy. Numerous spectra from multiple spots were collected on multiple samples for each compound and on each solution to ensure sample homogeneity. All Np solutions used for Raman spectral analysis were prepared individually by mixing an aliquot of the 0.24 M NpV stock solution with appropriate volumes of ACl stock solutions and H2O.

Molecular dynamics simulations

All-atom explicit-solvent MD simulations were performed using the package GROMACS (5.0.7)50. Force field parameters for NpVIO22+ and NpVO2+ ions and the recommended SPC/E water model given by Pomogaev et al.51 were used in all simulations. Additional details and calculated radial distribution functions are given in the Supplementary Methods and in Supplementary Figures 14 and 15.

Data availability

All data supporting this work are available within this manuscript or its associated Supplementary Information, or from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Additionally, crystallographic data for the compounds reported herein have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers CSD 1878175-1878177. These data can be obtained free of charge from the CCDC via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

References

Piro, N. A., Robinson, J. R., Walsh, P. J. & Schelter, E. J. The electrochemical behavior of cerium(III/IV) complexes: Thermodynamics, kinetics and applications in synthesis. Coord. Chem. Rev. 260, 21–36 (2014).

Lundgren, R. J. Stradiotto, M. in Ligand Design in Metal Chemistry: Reactivity and Catalysis, (eds Stradiotto, M & Lundgren, R., J.) pp 1–14 (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester, UK, 2016).

Arnold, P. L., Patel, D., Wilson, C. & Love, J. B. Reduction and selective oxo group silylation of the uranyl dication. Nature 451, 315–317 (2008).

Hayton, T. W. & Wu, G. Exploring the effects of reduction or Lewis acid coordination on the U=O bond of the uranyl moiety. Inorg. Chem. 48, 3065–3072 (2009).

Bell, N. L., Shaw, B., Arnol, P. L. & Love, J. B. Uranyl to Uranium(IV) conversion through manipulation of axial and equatorial ligands. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 3378–3384 (2018).

Tsui, E. Y., Tran, R., Yano, J. & Agapie, T. Redox−inactive metals modulate the reduction potential in heterometallic manganese−oxido clusters. Nat. Chem. 5, 293–299 (2013).

Levin, J. R., Dorfner, W. L., Carroll, P. J. & Schelter, E. J. Control of cerium oxidation state through metal complex secondary structures. Chem. Sci. 6, 6925–6934 (2015).

Marcus, Y. & Hefter, G. Ion pairing. Chem. Rev. 106, 4585–4621 (2006).

Denning, R. G. Electronic structure and bonding in actinyl ions and their analogs. J. Phys. Chem. A 111, 4125–4143 (2007).

Mougel, V. et al. Uranium and manganese assembled in a wheel-shaped nanoscale single-molecule magnet with high spin-reversal barrier. Nat. Chem. 4, 1011–1017 (2012).

Freiderich, J. W., Burn, A. G., Martin, L. R., Nash, K. L. & Clark, A. E. A combined density functional theory and spectrophotometry study of the bonding interactions of [NpO2·M]4+ cation–cation complexes. Inorg. Chem. 56, 4788–4795 (2017).

Sullivan, J. C., Hindman, J. C. & Zielen, A. J. Specific interaction between Np(V) and U(VI) in aqueous perchloric acid media. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 83, 3373–3378 (1961).

Sullens, T. A., Jensen, R. A., Shvareva, T. Y. & Albrecht-Schmitt, T. E. Cation-cation interactions between uranyl cations in a polar open-framework uranyl periodate. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 2676–2677 (2004).

Skanthakumar, S., Antonio, M. R. & Soderholm, L. A comparison of neptunyl(V) and neptunyl(VI) solution coordination: the stability of cation−cation interactions. Inorg. Chem. 47, 4591–4595 (2008).

Xian, L., Tian, G., Zheng, W. & Rao, L. Cation–cation interactions between NpO2 + and UO2 2+ at different temperatures and ionic strengths. Dalton Trans. 41, 8532–8538 (2012).

Jin, G. B. Three−dimensional network of cation–cation-bound neptunyl(V) squares: synthesis and in situ Raman spectroscopy studies. Inorg. Chem. 55, 2612–2619 (2016).

Vallet, V., Privalov, T., Wahlgren, U. & Grenthe, I. The mechanism of water exchange in AmO2(H2O)5 2+ and in the isoelectronic UO2(H2O) 5 + and NpO2(H2O)5 2+ complexes as studied by quantum chemical methods. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 7766–7767 (2004).

Konings, R. J. M., Morss, L. R., Fuger, J. in The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements (eds Morss, L. R., Edelstein, N. M., Fuger, J.) Vol. 4, pp 2113–2224 (Springer: The Netherlands, 2006).

Guillaumont, R. et al. Update on the chemical thermodynamics of uranium, neptunium, plutonium, americium and technetium 5 (Elsevier, New York, NY, 2003).

Allen, P. G., Bucher, J. J., Shuh, D. K., Edelstein, N. M. & Reich, T. Investigation of aquo and chloro complexes of UO2 2+, NpO2 +, Np4+, and Pu3+ by X-ray absorption fine structure spectroscopy. Inorg. Chem. 36, 4676–4683 (1997).

Soderholm, L., Antonio, M. R., Williams, C. & Wasserman, S. R. XANES spectroelectrochemistry: a new method for determining formal potentials. Anal. Chem. 71, 4622–4628 (1999).

Yamamura, T., Watanabe, N., Yano, T. & Shiokawa, Y. Electron-transfer kinetics of Np3+∕ Np4+, NpO2 +∕ NpO2 2+, V2+∕ V3+, and VO2+∕ VO2 + at carbon electrodes. J. Electrochem. Soc. 152, A830–A836 (2005).

Neck, V., Fanghänel, T., Rudolph, G. & Kim, J. I. Thermodynamics of neptunium(V) in concentrated salt solutions: chloride complexation and ion interaction (Pitzer) parameters for the NpO2 + Ion. Radiochim. Acta 69, 39–47 (1995).

Vallet, V., Wahlgren, U. & Grenthe, I. Probing the nature of chemical bonding in uranyl(VI) complexes with quantum chemical methods. J. Phys. Chem. A 116, 12373–12380 (2012).

Hennig, C., Ikeda-Ohno, A., Tsushima, S. & Scheinost, A. C. The sulfate coordination of Np(IV), Np(V), and Np(VI) in aqueous solution. Inorg. Chem. 48, 5350–5360 (2009).

Ikeda-Ohno, A. et al. Neptunium carbonato complexes in aqueous solution: an electrochemical, spectroscopic, and quantum chemical study. Inorg. Chem. 48, 11779–11787 (2009).

Morris, D. E. Redox energetics and kinetics of uranyl coordination complexes in aqueous solution. Inorg. Chem. 41, 3542–3547 (2002).

DeFord, D. D. & Hume, D. N. The determination of consecutive formation constants of complex ions from polarographic data. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 73, 5321–5322 (1951).

Basile, L. J., Sullivan, J. C., Ferraro, J. R. & LaBonville, P. The Raman scattering of uranyl and transuranium V, VI, and VII ions. Appl. Spectrosc. 28, 142–145 (1974).

Nguyen-Trung, C., Begun, G. M. & Palmer, D. A. Aqueous uranium complexes. 2. Raman spectroscopic study of the complex formation of the dioxouranium(VI) ion with a variety of inorganic and organic ligands. Inorg. Chem. 31, 5280–5287 (1992).

Fujii, T., Uehara, A., Kitatsuji, Y. & Yamana, H. Theoretical and experimental study of the vibrational frequencies of UO2 2+ and NpO2 2+ in highly concentrated chloride solutions. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 303, 1015–1020 (2015).

Guillaume, B., Begun, G. M. & Hahn, R. L. Raman spectrometric studies of "cation−cation" complexes of pentavalent actinides in aqueous perchlorate solutions. Inorg. Chem. 21, 1159–1166 (1982).

Matsika, S., Pitzer, R. M. & Reed, D. T. Intensities in the spectra of actinyl ions. J. Phys. Chem. A 104, 11983–11992 (2000).

Jin, G. B. Mixed-valent neptunium(IV/V) compound with cation–cation-bound six−membered neptunyl rings. Inorg. Chem. 52, 12317–12319 (2013).

Grigor’ev, M. S. & Krot, N. N. Synthesis and single crystal X-ray diffraction study of U(VI), Np(VI), and Pu(VI) perchlorate hydrates. Radiochemistry 52, 375–381 (2010).

Jin, G. B., Skanthakumar, S. & Soderholm, L. Three new sodium neptunyl(V) selenate hydrates: structures, raman spectroscopy, and magnetism. Inorg. Chem. 51, 3220–3230 (2012).

Austin, J. P., Sundararajan, M., Vincent, M. A. & Hillier, I. H. The geometric structures, vibrational frequencies and redox properties of the actinyl coordination complexes ([AnO2(L)n]m; An = U, Pu, Np; L = H2O, Cl−, CO3 2−, CH3CO2 −, OH−) in aqueous solution, studied by density functional theory methods. Dalton Trans. 0, 5902–5909 (2009).

Buckner, J. K. & Jorgensen, W. L. energetics and hydration of the constituent ion pairs of tetramethylammonium chloride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 111, 2507–2516 (1989).

Watson, L. A. & Hay, B. P. Role of the uranyl oxo group as a hydrogen bond acceptor. Inorg. Chem. 50, 2599–2605 (2011).

Marcus, Y. A Simple empirical model describing the thermodynamics of hydration of ions of widely varying charges, sizes, and shapes. Biophys. Chem. 51, 111–127 (1994).

Jin, G. B., Lin, J., Estes, S. L., Skanthakumar, S. & Soderholm, L. Influence of countercation hydration enthalpies on the formation of molecular complexes: a Thorium–nitrate example. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 18003–18008 (2017).

Burn, A. G., Martin, L. R. & Nash, K. L. Pentavalent neptunyl ([O≡Np≡O]+) cation–cation interactions in aqueous/polar organic mixed-solvent media. J. Solut. Chem. 46, 1299–1314 (2017).

Fukuzumi, S. et al. Crystal structure of a metal ion-bound oxoiron(IV) complex and implications for biological electron transfer. Nat. Chem. 2, 756–759 (2010).

Chaumont, A. & Wipff, G. Solvation of uranyl(II), europium(III) and uropium(II) cations in “basic” room-temperature ionic liquids: a theoretical study. Chem. - Eur. J. 10, 3919–3930 (2004).

Nash, K. L., Madic, C., Mathur, J. N., Lacquement, J. in The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements (eds Morss, L. R., Edelstein, N. M., Fuger, J.) Vol. 4, pp 2622–2798 (Springer: The Netherlands, 2006).

Binnemans, K. Lanthanides and actinides in ionic liquids. Chem. Rev. 107, 2592–2614 (2007).

Sjoblom, R. & Hindman, J. C. Spectrophotometry of neptunium in perchloric acid solutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 73, 1744–1751 (1951).

Bruker. APEX2, SAINT, SADABS (Bruker AXS Inc., Madison, WI, USA, 2012).

Sheldrick, G. M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr. 64, 112–122 (2008).

Hess, B., Kutzner, C., van der Spoel, D. & Lindahl, E. GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 4, 435–447 (2008).

Pomogaev, V. et al. Development and application of effective pairwise potentials for UO2 n+, NpO2 n+, PuO2 n+, and AmO2 n+ (n = 1, 2) Ions with Water. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15,15954-15963 (2013).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank L. Soderholm and M.R. Antonio for helpful discussions that improved the quality of this manuscript. This material is based on work supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Chemical Sciences, Geosciences, and Biosciences, and Heavy Element Chemistry program through Argonne National Laboratory. Argonne is a U.S. Department of Energy laboratory managed by UChicago Argonne, LLC, under contract DE-AC02-06CH11357. The computing resources, provided on Blues, a high-performance computing cluster operated by the Laboratory Computing Resource Center at Argonne National Laboratory, are gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.B.J. and S.L.E. designed the study. S.L.E. performed the voltammetry experiments and collected the Vis–NIR absorption spectra. G.B.J. performed the crystal syntheses, collected the crystallographic data, and collected the Raman spectra. B.Q. performed the MD simulations. All authors analyzed the data. All authors wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Journal peer review information: Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Estes, S.L., Qiao, B. & Jin, G.B. Ion association with tetra-n-alkylammonium cations stabilizes higher-oxidation-state neptunium dioxocations. Nat Commun 10, 59 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07982-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07982-5

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.