Abstract

Gas-sensing materials are becoming increasingly important in our society, requiring high sensitivity to differentiate similar gases like N2 and O2. For the design of such materials, the driving force of electronic host-guest interaction or host-framework changes during the sorption process has commonly been considered necessary; however, this work demonstrates the use of the magnetic characteristics intrinsic to the guest molecules for distinguishing between diamagnetic N2 and CO2 gases from paramagnetic O2 gas. While the uptake of N2 and CO2 leads to an increase in TC through ferrimagnetic behavior, the uptake of O2 results in an O2 pressure-dependent continuous phase change from a ferrimagnet to an antiferromagnet, eventually leading to a novel ferrimagnet with aligned O2 spins following application of a magnetic field. This chameleonic material, the first with switchable magnetism that can discriminate between similarly sized N2 and O2 gases, provides wide scope for new gas-responsive porous magnets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In this Internet of Things age1, it is essential to control how information is processed when only slight differences within the data exist, leading to the notion of sensing. The development of highly sensitive devices for ubiquitous gas and innocuous small molecule sensing is one of the major challenges in the field of materials science2. A magnetic change can be beneficial for providing a responsive signal in such a sensing device, and would be advantageous for gas detection owing to contactless operation and detection independent of the sample shape of the host framework. Further, devices that respond quickly with easy operability and readability for ON/OFF updates are desirable; the availability of spin freedom in host-guest interactions for gas sensing is an innovative technique that could make this possible. For instance, distinguishing between nitrogen (N2) and oxygen (O2) gases is exceedingly difficult because of their similar size and boiling points3,4. Detecting a magnetic change induced by the intrinsic magnetic nature of these gases (i.e., diamagnetic N2 and paramagnetic O2) would represent a major breakthrough in gas-sensing technologies. For this purpose, however, a drastic phase change in magnetism, not just small modifications of magnetic properties5,6, is necessary. The gas-induced magnetic response has also been investigated using FeII spin-crossover systems;7,8,9 however, magnetic discrimination between O2 and N2 has never been observed. Meanwhile, drastic magnetic changes induced by solvation/desolvation10 have prompted lively discussions on magnetic sponges11,12,13,14,15,16,17 and spin-crossover systems18,19,20,21. Despite this, a strong magnetic response to gases in air such as N2, O2, and carbon dioxide (CO2), which possess relatively small sizes and low or no reactivity and electric polarity, remains a significant challenge for the development of functional porous magnetic materials.

Here, we report a porous layered ferrimagnet that reversibly alters its magnetic phase in response to the magnetic type of the inserted gas, i.e., diamagnetic for N2 and CO2 or paramagnetic for O2. The fully O2-adsorbed compound changes to an antiferromagnet, but application of a magnetic field results in a unique ferrimagnetic phase where some of the oxygen spins become aligned synergistically. Recently, the control of spin coupling on oxygen molecules inserted into molecular porous frameworks22,23,24,25,26,27 or graphite28,29, as well as in bulk materials30,31,32,33, has been seen as an important topic. Nevertheless, this is the first case in which a paramagnetic phase resulting from condensed oxygen molecules plays a key role for long-range ordering in an O2-accommodated magnet.

Results

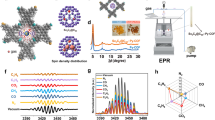

Crystal structure of the pristine framework

To develop gas-responsive porous magnets, we chose a layered ferrimagnet, [{Ru2(3,5-F2PhCO2)4}2{TCNQ(MeO)2}]·3(DCM)·1.5(DCE) (1-solv; 3,5-F2PhCO2– = 3,5-difluorobenzoate; TCNQ(MeO)2 = 2,5-dimethoxy-7,7,8,8-tetracyanoquinodimethane; DCM = dichloromethane; DCE = 1,2-dichloroethane), obtained from an electron-donor (D)/-acceptor (A) 2:1 assembly that involves an electron transfer15,34,35,36,37,38,39,40, where the paddlewheel-type [Ru2(3,5-F2PhCO2)4] subunit (abbreviated as [Ru2]) is D and TCNQ(MeO)2 is A. Compound 1-solv crystallized in the triclinic space group P−1, where two different [Ru2] units and one TCNQ(MeO)2 molecule, with respective inversion centers, were structurally isolated (Z = 1) with a charge assignment of [–{Ru(1)2II,III}+–μ4-TCNQ(MeO)2•––{Ru(2)2II,II}–] (Fig. 1a,b, Supplementary Fig. 1a, Supplementary Table 1−3, Supplementary Note 1 and 2). The set of two [Ru2] units and TCNQ(MeO)2 constructs a fishnet-like two-dimensional network lying on the (100) plane that stacks along the a-axis (Fig. 1a,b). The inter-layer distances defined by the vertical (l1) and inter-unit translational (l2 = a-axis; Fig. 1b) distances between the planes are 9.78 Å and 10.65 Å, respectively (Supplementary Table 8), and the crystallization solvents (3(DCM)·1.5(DCE)) are located between the layers with a solvent accessible volume of 713 Å3 (32% of total volume).

Structural modulation and magnetic sponge behavior upon solvation/desolation. a–d Views of the crystal structures of 1-solv (a, b) and 1 (c, d); figures a, c and b, d show projections along the a (a’) axis and c (c’) axis, respectively, where atoms N, O, C, F, and Ru are represented in blue, red, gray, green, and purple, respectively, and the crystallization solvents given in figures a and b are represented in cyan. The vertical inter-layer distance (l1) is indicated in blue digit in b and d, and the inter-unit translational distance (l2) corresponds to the a- or a′-lattice axis for each compound (Supplementary Table 8). The cell axes a′–c′ in c and d represent those for a transformed lattice (see Supplementary Methods), which were adopted for easy comparison with the lattice of 1-solv. e Schematic representation for the interchange between 1-solv and 1 upon solvation/desolvation, where the colored arrow indicates a plausible direction of ordered spins. f Temperature dependence of magnetic susceptibility (χ) for 1-solv (red) and 1 (black) measured under a 1 kOe dc field (Hdc) on field cooled process. Inset: Remnant magnetization (M) at Hdc = 0 Oe (heating process) measured after taking a FCM (1.8–120 K) under a 3 Oe dc field, where the dashed lines indicate the respective TC values

Crystal structure of the dried phase

Compound 1-solv gradually releases the crystallization solvents upon increasing temperature, producing the solvent-free porous compound [{Ru2(3,5-F2PhCO2)4}2{TCNQ(MeO)2}] (1), which is stable at temperatures up to 450 K with its crystallinity intact (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Similar to 1-solv, 1 crystallized in the triclinic P−1 space group (Z = 1, Fig. 1c,d, Supplementary Fig. 1b, Supplementary Table 1−3, Supplementary Note 1 and 2). Although the fishnet-like network was preserved with a slightly shortened (relative to 1-solv) l1 of 9.46 Å, while with a lengthened l2 of 10.84 Å ( = a′-axis; Fig. 1d), the structural features of the network are drastically altered from an almost flat form in 1-solv to a wavy form in 1 (Fig. 1c,d,e), resulting in a reduction of the void volume to 147 Å3 (7.5% against total volume). Of note, the electronic state of [Ru2] and TCNQ(MeO)2 units in 1 remains unchanged (Supplementary Table 2, 3, Supplementary Note 1). Compound 1 becomes 1-solv when exposed to DCM/DCE vapor for 12 h at 300 K (Supplementary Fig. 2b), indicating a common magnetic sponge behavior (vide infra).

Magnetic sponge behavior

The spins of the [Ru2II,II] (S = 1) and [Ru2II,III]+ (S = 3/2) moieties interact antiferromagnetically with the radical spin of TCNQ(MeO)2•–41,42 over the layered network forming a ferrimagnetically ordered layer, which is followed by three-dimensional ferrimagnetic ordering with inter-layer ferromagnetic interactions15,34,36,38,39,40. The magnetic transition temperature TC (or TN for antiferromagnetic ordering) for this type of layered magnetic material should be strongly affected by intra-layer exchange interactions between the [Ru2]0/+ units and TCNQ(MeO)2•–, as well as inter-layer dipole interactions15,36,38,39,40,43. Figure 1f shows the temperature dependence of field-cooled dc magnetization (FCM) of 1-solv and 1 in a 1 kOe dc field (Hdc). In both compounds, an abrupt increase in the FCM is observed near 80 K without a subsequent decrease at lower temperatures. This occurs independent of the applied fields, indicating the onset of ferrimagnetic ordering35,37 (details of the comparison between 1-solv and 1 are described in Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Note 3 and 4); however, their TC values differ (i.e., 83 K and 76 K for 1-solv and 1, respectively), as evaluated from remnant magnetization (RM) (inset of Fig. 1f) and ac susceptibility data (Supplementary Fig. 3b, e, Supplementary Note 3).

Gas sorption capability

In addition to the magnetic sponge capabilities for crystallization solvents, 1 has the ability to adsorb gases such as CO2, N2, and O2; the gas-adsorbed phase is defined as 1 ⊃ Gas. Figure 2a shows their sorption isotherms (a log-scale plot is shown in Supplementary Fig. 4). For N2, 1 has a nonporous nature at 77 K because of the slow diffusion of gaseous molecules into the void space; however, 1 acts as an adsorbent at 120 K, where the 1st gate-opening is observed at a pressure of 3.2 kPa, as found in other low-dimensional porous systems44, and reaches an adsorption amount of 27 mL (stp) g−1 (2.3 mol per formula unit) at 99 kPa. The CO2 adsorption isotherm at 195 K shows a steep rise at relatively low pressures, where the adsorption amount is 102 mL (stp) g−1 (8.7 mol per formula unit) at 99 kPa45, even though a gate-opening modification should be involved. The O2 adsorption isotherm at 90 K shows a stepwise feature; 1st and 2nd gate-opening transitions at ca. 0.1 kPa and 36 kPa, respectively, reaching an adsorbed amount of 110 mL (stp) g−1 (9.5 mol per formula unit) at 99 kPa; however, only the 1st gate-opening at ca. 3.1 kPa is observed when measured at 120 K, eventually reaching an adsorbed O2 amount of 64 mL (stp) g−1 (5.5 mol per formula unit) at 99 kPa.

Gas sorption capability, sorption-induced structural transitions, and crystal structures under gases. a Adsorption (closed) and desorption (open) isotherms of 1 for CO2 at 195 K (green), N2 at 77 K (orange) and 120 K (red), O2 at 90 K (blue) and 120 K (cyan), where solid lines are only guide for the eye. b PXRD patterns measured (λ = 1.54 Å) under 100 kPa of N2 at 130 K (red), O2 at 130 K (cyan) and 94 K (blue), and CO2 at 204 K (green) and ones for 1 (black) and 1-solv (purple) at 298 K. c Packing views (c′-axis projection, where atoms N, O, C, F, and Ru are represented in blue red, gray, green, and purple, respectively) of 1 ⊃ N2 at 130 K, (upper left), 1 ⊃ O2-I at 130 K (lower left), 1 ⊃ O2-II at 94 K (lower right), and 1 ⊃ CO2 at 195 K (upper right) and their transformation routes including 1-solv and 1, where the structures for 1 ⊃ N2, 1 ⊃ O2-I, and 1 ⊃ CO2 were determined by in situ SCXRD analyses, and it for 1 ⊃ O2-II was evaluated from the PXRD pattern with the Rietveld refinement (the accommodated gas molecules in a space filling model, of which the site occupancy is colored, are only represented in 1 ⊃ N2, 1 ⊃ O2-I, and 1 ⊃ CO2, and minor position-disordered components in a part of layer framework in 1 ⊃ O2-I were omitted for clarity). The a′–c′ axes represent those of a transformed lattice for easy comparison with the lattice of 1-solv (see Supplementary Methods). The vertical inter-layer distances (l1) are indicated in blue digit, and the inter-unit translational distance (l2) corresponds to the a′-lattice axis for each compound (Supplementary Table 8). d A close-up view of gas-sandwiched mode at Site-A (Supplementary Fig. 10) denoted as an yellow ellipse in figure c for 1 ⊃ O2-I and 1 ⊃ N2

Crystal structures under gases

To elucidate the gas-inserted structure, in situ powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) of 1 were measured under 100 kPa of N2 at 130 K, O2 at 94 and 130 K, and CO2 at 204 K (Fig. 2b), which illustrate the occurrence of structural transformations upon gas adsorption. Two types of gas-adsorbed temperature-dependent phases exist at 130 and 94 K under O2, which can be associated with the 2nd gate-opening step in the adsorption isotherm for O2. Additionally, the PXRD pattern of 1 ⊃ O2 at 130 K is very similar to that of 1 ⊃ N2 at 130 K in that it does not undergo the 2nd gate-opening transition. Hereafter, O2-adsorbed phases observed at 130 K and 94 K are denoted as 1 ⊃ O2-I and 1 ⊃ O2-II, respectively. Notably, the gas-induced structural changes are reversible (Supplementary Fig. 5); after evacuating the CO2 gas from 1 ⊃ CO2, the PXRD pattern reverts to the original pattern of 1. In the case of 1 ⊃ N2, slight heating to 150 K in addition to evacuation is required to promote desorption of N2. Of note, the PXRD pattern for 1 ⊃ O2-II becomes that for 1 ⊃ O2-I by evacuating at 94 K, but it does not return to the pattern of 1, indicating that the 1 ⊃ O2-I phase corresponds to an intermediate phase stabilized at low pressures of O2 even at 94 K (vide infra), which eventually turns into 1 after evacuating at 300 K.

Finally, the crystal structures of 1 ⊃ N2, 1 ⊃ O2-I, and 1 ⊃ CO2 were determined by in situ single crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) under gas-pressure controlled atmospheres (Supplementary Fig. 6, 7, 9, and 10, Supplementary Table 4−6, Supplementary Note 5−7), and it of 1 ⊃ O2-II was evaluated from the in situ PXRD data using the Rietveld refinement technique (Supplementary Fig. 8, Supplementary Table 7, Supplementary Note 6). For 1 ⊃ N2, 1 ⊃ O2-I, and 1 ⊃ CO2, the accommodated gases were reasonably determined with occupancy numbers of 4N2, 5.2O2, and 5CO2, respectively, which were displayed in Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 9 and 10 (the O2 molecules for 1 ⊃ O2-II have less accuracy, so only the framework structure is discussed). The inter-layer distances, which are defined by l1 and l2 ( = a′-axis) between planes, have decreased (but l2 > 10.3 Å; Supplementary Table 8, where inter-layer ferromagnetic interaction is expected even for 1 ⊃ O2-I and 1 ⊃ O2-II)39,40 in all 1 ⊃ Gas structures compared to 1, which manifests structurally as a change from the wavy layer form in 1 to a quasi-flat layer form in 1 ⊃ Gas, resulting from a reduction in the Ru−N−C bending angle (av. 159–161° for 1 ⊃ Gas vs. 140.3° for 1, Supplementary Table 8). Hence, the guest-molecule accessible volume between the layers in 1 ⊃ Gas increase relative to 1 (147 Å3), as expected from the gas adsorption capability (335–546 Å3 for 1 ⊃ Gas, Supplementary Table 8). Importantly, the structural frameworks of 1 ⊃ N2 and 1 ⊃ O2-I at 130 K are almost identical; three distinguishable gas-accommodation sites (Site-A–C; Supplementary Fig. 10) were commonly realized even for 1 ⊃ CO2, where a close-up view of gas-sandwiched mode at Site-A, which was most likely associated with the difference of magnetism between 1 ⊃ N2 and 1 ⊃ O2-I (vide infra), was depicted in Fig. 2d. The Site-A included two molecules of N2 or O2 with a similar arrangement; two gas molecules at Site-A were relatively close to the TCNQ(MeO)2 moieties, where the barycenter-to-barycenter distance between N2/O2 and the quinonoid ring (C6) of the TCNQ(MeO)2 moiety was 3.79(5) and 3.86(5) Å, respectively, and the inter-guest barycenter distance of N2···N2/O2···O2 was 4.82(6) and 4.85(6) Å, respectively (Fig. 2d). The torsion angle of C6···N2/O2···N2/O2 was 114.8(3)˚ and 114.6(3)˚ for 1 ⊃ N2 and 1 ⊃ O2-I, respectively (Fig. 2d). To accommodate an additional 4–8 mol per formula unit of gas, a subsequent enlargement in the inter-layer distance is required, as observed in 1 ⊃ O2-II and 1 ⊃ CO2 (Fig. 2c).

Magnetic properties under diamagnetic gases, CO2 and N2

Upon gas adsorption, a significant structural change is induced without alteration in the oxidation state of each unit in the D2A layer; in situ infrared (IR) spectroscopy proves the preservation of TCNQ(MeO)2•–, even under a 100 kPa gas atmosphere (Supplementary Fig. 11). Therefore, in situ magnetic measurements were conducted in Quantum Design MPMS-7S by accurately handling the gas pressure; the pressure in a homemade cell (Supplementary Fig. 12) containing the sample was evacuated down to 0.1 Pa with a turbo-molecular pump at 353 K and the gas was introduced at 200 K up to an inner gas pressure of ~116 kPa. The gas-sealed cell was then cooled at a sweep rate of 0.5 K min–1 to 120 K for N2, 195 K for CO2, and 100 K for O2. Each cell was maintained at its respective temperature for 10 h to reach adsorption equilibrium. Once the inner pressure of each cell was obtained, the gas-sealed cell was held at 100 K or 120 K for the FCM measurements.

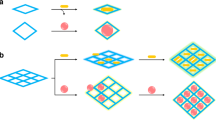

Figure 3a shows the temperature dependence of FCM at 100 Oe for 1 ⊃ N2 and 1 ⊃ CO2 prepared in situ, together with that for 1. Upon insertion of N2 and CO2, TC drastically increases to 88 K for 1 ⊃ N2 and 92 K for 1 ⊃ CO2 from 76 K for 1 (under vacuum) even under a weaker magnetic field of 5 Oe (Supplementary Fig. 13), establishing the existence of a ferrimagnetic ground state under N2 and CO2 atmospheres, where TC was determined from a disappeared point of RM (Supplementary Fig. 14). Since N2 exists in the gas phase at 88 K in bulk, the change in TC is not caused by external N2. In addition, N2 and CO2 are diamagnetic species. Therefore, the variation in TC results from the adsorbed gases. Given that the decrease in TC from 1-solv to 1 was induced by considerable structural changes, inversely, the increase in TC for 1 ⊃ N2 and 1 ⊃ CO2 relative to 1 likely results from a reduction in structural deformation; the wavy layer in 1 is modified into a quasi-flat layer in 1 ⊃ N2 and 1 ⊃ CO2 and/or a modification in the inter-layer environment occurs, resulting from closely packed gases (Fig. 3c). Even with such a drastic change in TC, the magnetic-field dependence of the magnetization (M–H) is essentially preserved from 1 (Fig. 3b), although the coercive field (Hc) of 1 ⊃ CO2 is somewhat larger than that of 1 and 1 ⊃ N2. Note that the anomalous steps around zero field for 1, 1 ⊃ N2, and 1 ⊃ CO2 (1 ⊃ O2 as well; vide infra) could be caused by a small number of free crystals that follow the magnetic field.

Variation of magnetic properties under diamagnetic gases, CO2 and N2. a FCM curves at a 100 Oe magnetic field for 1 measured under vacuum (black) and 1 ⊃ CO2 (green) and 1 ⊃ N2 (red) under a 100 kPa gas atmosphere. b Magnetic hysteresis loops at 1.8 K for 1 measured under vacuum (black), 1 ⊃ CO2 (green), and 1 ⊃ N2 (red) under a 100 kPa gas atmosphere. c Schematic representation for the alternation between 1 and 1 ⊃ CO2 and 1 ⊃ N2 upon CO2 and N2 adsorptions, respectively

Magnetic properties under a paramagnetic O2 gas

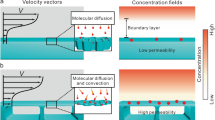

The magnetic behavior of the material under an O2 atmosphere is completely different from that under N2 and CO2 and varies with the O2 pressure (PO2) (Fig. 4). Similar to 1 ⊃ N2 and 1 ⊃ CO2, the TC of 1 ⊃ O2 increases once at low pressures of PO2 < 1 kPa (e.g., TC = 90 K at PO2 ≤ 0.1 kPa; vacuum pressure level at 100 K). However, under higher pressures, the FCM curve shows an anomaly with a cusp, indicating the onset of antiferromagnetic ordering; for example, TN = 71 K at 1 kPa, which gradually increases to TN = 98 K at 100 kPa with increasing O2 pressure (Fig. 4a). The variation in TN with O2 pressure was also confirmed by the magnetization measurements by varying the O2 pressure at each temperature (Supplementary Fig. 15). The initial increase in TC at low O2 pressures (PO2 < 1 kPa) is likely caused by the same mechanism found in 1 ⊃ N2 and 1 ⊃ CO2 (Fig. 3c), which could be attributed to the redress of the layered structure, i.e., the modification from a wavy form of 1 to a quasi-flat form in 1 ⊃ O2-I (the first step in Fig. 4b). Meanwhile, the drastic change of the magnetic phase from ferrimagnetism to antiferromagnetism could be obtained whether for: (1) a structural change associated with the transformation from 1 ⊃ O2-I to 1 ⊃ O2-II, or (2) the magnetic contribution of the adsorbed O2 molecules. To examine these possibilities, PXRD patterns (from both of common lab level and high resolution synchrotron level) were measured by varying the O2 pressure at a fixed temperature in the range of 70–100 K (Supplementary Fig. 16 and 17), and the structural transition pressure (Pc) from 1 ⊃ O2-I to 1 ⊃ O2-II at each temperature was plotted in a T–PO2 phase diagram together with TN, where the TN line separates the magnetic phases between the paramagnetic/ferrimagnetic phase and the antiferromagnetic phase, and the Pc line distinguishes between the 1 ⊃ O2-I and 1 ⊃ O2-II phases (Fig. 5). Importantly, the TN line is independent of the Pc line, and antiferromagnetism in the 1 ⊃ O2-I phase is present (the pale blue area in Fig. 5). Since the 1 ⊃ O2-I and 1 ⊃ N2 structures are identical with l2 > 10.3 Å expected as a regime for inter-layer ferromagnetic interactions39,40, and indeed, 1 ⊃ N2 is ferrimagnetic, the antiferromagnetism in 1 ⊃ O2-I results from the magnetic contribution of the adsorbed O2 molecules, which is caused by long-range antiferromagnetic correlations via intercalated O2 spins; the most likely packing mode associated with the O2-mediated magnetic pathway was shown in Fig. 2d. Further, the continuous shift in TN is likely dependent on the number of O2 spins between layers, which act as magnetic mediators couple layer’s ordered spins together (Fig. 4b). Thus, the present porous layered magnet 1 magnetically discriminates O2 from N2 and CO2, at least at PO2 ≥ 1 kPa.

Variation of magnetic properties under a paramagnetic O2 gas. a O2-pressure dependence of FCM curves at a 100 Oe magnetic field for 1. b Schematic representations for the alternations of 1 ⊃ O2 dependent on the applied O2 pressure and external magnetic fields. c Field-dependence of the magnetization at 1.8 K for 1 measured at several O2 pressures, where the inset represents the differential plots on the basis of the M−H curve for 1

Structural and magnetic phase diagram for 1 under an O2. Red and blue closed-circles represent TC and TN for ferrimagnetic and antiferromagnetic orderings, respectively, which were determined from the M–T curves (Fig. 4a) measured under each O2 pressure fixed at 100 K. Blue closed-triangles represent TN for antiferromagnetic ordering determined from the magnetization measurements by varying the O2 pressure at each fixed temperature (Supplementary Fig. 15). Green closed-circles represent the structural transition pressure (Pc) from 1⊃O2-I to 1⊃O2-II determined by PXRD measurements by varying the O2 pressure at each fixed temperature (Supplementary Fig. 16). Red dotted line separates magnetic phases between the paramagnetic (Para) phase and ferrimagnetic (F) phase. Blue dotted line (TN line) separates magnetic phases between the Para/F phase and the antiferromagnetic (AF) phase. The green dotted line (Pc line) separates the 1⊃O2-I and 1⊃O2-II phases. Black dotted line represents the saturated vapor pressure curve, which distinguishes between the gas phase and non-gas phase for bulk O2

The magnetic switching between the ferrimagnetic phase under vacuum with the 1 ⊃ O2-I structure and the antiferromagnetic phase of 1 ⊃ O2 is quite fast and reversible (Fig. 6); the change from the ferrimagnetic phase to the antiferromagnetic phase is completed in <1 min at 85 K.

Generally, the solid states of bulk O2 exist in the α-dimer form with a spin singlet at T < 24 K30,46. Compound 1 ⊃ O2-II eventually has ~9 O2 molecules per D2A layer unit, like a buried oxygen layer between ferrimagnetic D2A layers; at least, some of them certainly act as a paramagnetic mediator in the pores. Interestingly, the antiferromagnetic phase of 1 ⊃ O2-II transforms to a ferrimagnetic phase in the presence of an applied magnetic field (Supplementary Fig. 18), giving the much higher saturated magnetization (Ms) value of 9.29 NμB compared to 2.22 NμB for 1 at 7 T (1.8 K), including a fully opened hysteresis curve (Hc = 0.70 T) (Fig. 4c). On the basis of the M–H curve for 1, the differential plots clarify the contribution of the O2 spins in the bulk magnetism of 1 ⊃ O2-II (Fig. 4d), giving rise to a new magnetic field-induced ferrimagnet. These magnetic alternations by gases are completely reversible upon adsorption/desorption under vacuum with heating (Supplementary Fig. 19).

Discussion

The magnetic change caused by the introduction of guest gas molecules into a porous magnet can be attributed to three triggers: (i) an electronic trigger that causes spin emergence in the frameworks as a result of host-guest electron transfers (i.e., formation of new magnetic pathways in the framework); (ii) a structural trigger resulting from magnetostructural modifications associated with gate-opening/-closing transitions induced by gas adsorption/desorption, respectively (i.e., modification of the magnetic pathways); and (iii) a paramagnetic guest trigger resulting from the formation of new magnetic pathways or dipole–dipole interactions where paramagnetic gas molecules themselves magnetically mediate the transition to another magnetic ground state. The present gas-responsive porous magnet results from triggers (ii) and (iii); in particular, the insertion of free oxygen molecules achieves a magnetic phase change from a ferrimagnet to an antiferromagnet based on trigger (iii). The fact of magnetic ordering via paramagnetic O2 molecules gives an opportunity to investigate the intrinsic nature of oxygen molecules in closed nano-sized porous spheres and provides a new application methodology based on paramagnetic molecules as switchable magnetic mediators. As a rapidly emerging field, this class of gas-responsive porous magnets is the most important target in the development of functional molecular porous materials.

Methods

Physical measurements

IR spectra were measured with KBr pellets using a Jasco FT/IR-4200 spectrometer. Thermogravimetric analyses (TGA) were performed using a Shimadzu DTG-60H apparatus under a N2 atmosphere in the temperature range from 298 K to 673 K at a heating rate of 5 K min–1. Unless otherwise noted, PXRD were collected on a Rigaku Ultima IV diffractometer with Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) at room temperature for the sample sealed in a silica glass capillary with an inner diameter of 0.5 mm with θ scan. PXRD patterns for 1 ⊃ O2 and 1⊃N2 with the synchrotron radiation (λ = 0.799999(6) Å) were collected at SPring-8 (BL44B2)47. Magnetic susceptibility measurements were performed using a Quantum Design SQUID magnetometer MPMS-XL on a polycrystalline sample in the temperature range of 1.8–300 K at a dc field of 1 kOe. Diamagnetic contributions were collected for the sample holder, Nujol, and for the sample using Pascal’s constants48. Fresh samples taken immediately from the stock liquids were used for the magnetic measurements of 1-solv, and the formula determined by single-crystal X-ray crystallography was used for data analyses. Details for in situ IR spectra and gas adsorption-magnetic measurements are described in Supplementary Methods.

X-Ray crystallographic analysis for 1-solv, 1, 1 ⊃ N 2, 1 ⊃ O 2 -I, and 1 ⊃ CO 2

Crystal data for 1-solv, 1, 1 ⊃ N2, 1 ⊃ O2-I, and 1 ⊃ CO2 were collected at 134 K, 112 K, 130 K, 130 K, and 195 K, respectively, on a CCD diffractometer (Rigaku Saturn724) with multi-layer mirror monochromated Mo-Kα radiation (λ = 0.71075 Å). Details for the measurements and structural determination are described in Supplementary Methods. These data have been deposited as CIFs at the Cambridge Data Centre as supplementary publication nos. CCDC-1519242, 1519241, 1519243, 1519244, and 1519240 for 1-solv, 1, 1 ⊃ N2, 1 ⊃ O2-I, and 1 ⊃ CO2, respectively. Structural diagrams were prepared using VESTA software49. The void volumes in the crystal structures were estimated using PLATON50.

Gas adsorption measurements

The sorption isotherm measurements for N2 (at 77 and 120 K), O2 (at 90 and 120 K), and CO2 (at 195 K) gas were performed using an automatic volumetric adsorption apparatus (BELSORP max; BEL Inc). A known weight (ca. 30 mg) of the dried sample was placed into the sample cell and then, prior to measurements, was evacuated using the degas function of the analyzer for 12 h at 353 K. The change in pressure was then monitored and the degree of adsorption was determined by the decrease in pressure at the equilibrium state.

Gas atmosphere PXRD measurements and Structural determination of 1 ⊃ O 2 -II

A ground sample of 1 was sealed in a silica glass capillary with an inner diameter of 0.5 mm. The PXRD pattern was obtained with a 0.02° step using an Ultima IV diffractometer with Cu-Κα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) with θ scan. To obtain the PXRD patterns under the gas-adsorbed conditions, the glass capillary was connected to stainless-steel (SUS) lines with valves to dose and remove the gas, which were connected to a gas-handling system (BELSORP max; BEL inc). The temperature was controlled by a N2 gas stream. Structures are determined using DIFFRACplus TOPAS® v4.2 software, FOX software51, and RIETAN-FP software52. Details for structural determination are described in Supplementary Methods. These data have been deposited as CIFs at the Cambridge Data Centre as supplementary publication nos. CCDC-1519245.

Data availability

The data sets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers 1519240-1519245. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

References

Vermesan, O. et al. Internet of things strategic research roadmap. in internet of things: global technological and societal trends. In: Vermesan, O., Friess, P., (eds). pp. 9−52 (River Publishers: Delft, The Netherlands, 2011).

Potyrailo, R. A. Multivariable sensors for ubiquitous monitoring of gases in the era of internet of things and industrial internet. Chem. Rev. 116, 11877–11923 (2016).

Poling, B. E., Prausnitz, J. M. & O’Connell, J. P. The Properties of Gases and Liquids. 5th edn, (McGraw-Hill, New York, 2000).

Smith, A. R. & Klosek, J. A review of air separation technologies and their integration with energy conversion processes. Fuel Process. Technol. 70, 115–134 (2001).

Navarro, J. A. R. et al. Guest-induced modification of a magnetically active ultramicroporous, gismondine-like, copper(II) coordination network. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 3978–3984 (2008).

Kaye, S. S., Choi, H. J. & Long, J. R. Generation and O2 adsorption studies of the microporous magnets CsNi[Cr(CN)6] (T C = 75 K) and Cr3[Cr(CN)6]2·6H2O (T N = 219 K). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 16921–16925 (2008).

Southon, P. D. et al. Dynamic interplay between spin-crossover and host-guest function in a nanoporous metal-organic framework material. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 10998–11009 (2009).

Arcís-Castillo, Z. et al. Reversible chemisorption of sulfer dioxide in a spin crossover porous coordination polymer. Inorg. Chem. 52, 12777–12783 (2013).

Coronado, E., Giménez-Marqués, M., Espallargas, G. M., Rey, F. & Vitórica-Yrezábal, I. J. Spin-crossover modification through selective CO2 sorption. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 15986–15989 (2013).

Coronado, E. & Espallargas, G. M. Dynamic magnetic MOFs. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 1525–1539 (2013).

Maspoch, D., Ruiz-Molina, D. & Veciana, J. Old materials with new tricks: multifunctional open-framework materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 36, 770–818 (2007).

Dechambenoit, P. & Long, J. R. Microporous magnets. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 3249–3265 (2011).

Maspoch, D. et al. A nanoporous molecular magnet with reversible solvent-induced mechanical and magnetic properties. Nat. Mater. 2, 190–195 (2003).

Ohkoshi, S., Arai, K., Sato, Y. & Hashimoto, K. Humidity-induced magnetization and magnetic pole inversion in a cyano-bridged metal assembly. Nat. Mater. 3, 857–861 (2004).

Motokawa, N. et al. Reversible magnetism between an antiferromagnet and a ferromagnet related to solvation/desolvation in a robust layered [Ru2]2TCNQ charge-transfer system. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 11943–11951 (2010).

Larionova, J. et al. Dramatic modifications of magnetic properties through dehydration-rehydration process of the molecular magnetic sponges CoCu(obbz)(H2O)4·2H2O and CoCu(obze)(H2O)4·2H2O, with obbz = N,N’-Bis(2-carboxyphenyl)oxamido and obze = N-(2-Carboxyphenyl)-N’-(carboxymethyl)oxamido. Inorg. Chem. 36, 6374–6381 (1997).

Zhang, J., Kosaka, W., Sugimoto, K. & Miyasaka, H. Magnetic sponge behavior via electronic state modulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 5644–5652 (2018).

Halder, G. J., Kepert, C. J., Moubaraki, B., Murray, K. S. & Cashion, J. D. Guest-dependent spin crossover in a nanoporous molecular framework material. Science 298, 1762–1765 (2002).

Niel, V. et al. Crystalline-state reaction with allosteric effect in spin-crossover, interpenetrated networks with magnetic and optical bistability. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42, 3760–3763 (2003).

Halder, G. J. et al. Elucidating the mechanism of a two-step spin transition in a nanoporous metal−organic framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 17552–17562 (2008).

Ohba, M. et al. Bidirectional chem-switching of spin state in a microporous framework. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 4767–4771 (2009).

Mori, W. et al. Magnetic properties of oxygen physisorbed in Cu-tans-1,4-cyclohexanedicarboxylic acid. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 306, 1–7 (1997).

Kitaura, R. et al. Formation of a one-dimensional array of oxygen in a microporous metal-organic solid. Science 298, 2358–2361 (2002).

Takamizawa, S., Nakata, E. & Akatsuka, T. Magnetic behavior of a 1D molecular-oxygen system included within a transformable single-crystal adsorbent. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 2216–2221 (2006).

Hori, A. et al. Spin-dependent molecular orientation of O2−O2 dimer formed in the nanoporous coordination polymer. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 82, 084703 (2013).

Hori, A. et al. High-field magnetization process of O2 adsorbed in a microporous coordination polymer CPL-1 at various temperatures. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 200, 022018 (2010).

Kobayashi, T. C. et al. Magnetic properties of molecular oxygen adsorbed in micro-porous metal-organic solids. Prog. Theor. Phys. Suppl. 159, 271–279 (2005).

Murakami, Y. et al. Neutron diffraction study of oxygen monolayers. Phys. B 213–214, 233–235 (1995).

Murakami, Y. & Suematsu, H. Magnetic and melting transitions of oxygen monolayers and multilayers physisorped on exfoliated graphite. Phys. Rev. B 54, 4146–4154 (1996).

Kanda, E., Haseda, T. & Ôtsubo, A. Paramagnetic susceptibility of solid oxygen. Physica 20, 131–132 (1954).

DeFotis, G. D. Magnetism of solid oxygen. Phys. Rev. B 23, 4714–4740 (1981).

Nomura, T. et al. Novel phase of solid oxygen induced by ultrahigh magnetic fields. Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 247201 (2014).

Kobayashi, T. C. et al. Emergence of novel phase of solid oxygen in ultrahigh magnetic field. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 568, 042018 (2014).

Miyasaka, H. Control of charge transfer in donor/acceptor metal−organic frameworks. Acc. Chem. Res. 46, 248–257 (2013).

Miyasaka, H., Campos-Fernández, C. S., Clérac, R. & Dunbar, K. R. Hexagonal layered materials composed of [M2(O2CCF3)4] (M = Ru and Rh) donors and TCNQ acceptors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 39, 3831–3835 (2000).

Miyasaka, H., Izawa, T., Takahashi, N., Yamashita, M. & Dunbar, K. R. Long-range ordered magnet of a charge-transfer Ru2 4+/TCNQ two-dimensional network compound. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 11358–11359 (2006).

Fukunaga, H. et al. A charge-disproportionate ordered state with δ=0.75 in a chemically sensitive donor/acceptor Dδ+2A2δ− layered framework. Chem. Commun. 51, 7795–7798 (2015).

Kosaka, W., Fukunaga, H. & Miyasaka, H. Electron-transferred donor/acceptor ferrimagnet with T C = 91 K in a layered assembly of paddlewheel [Ru2] units and TCNQ. Inorg. Chem. 54, 10001–10006 (2015).

Kosaka, W., Itoh, M. & Miyasaka, H. Metamagnetism with T N = 97 K in a layered assembly of paddlewheel [Ru2] units and TCNQ: an empirical rule for interlayer distances determining the magnetic ground state. Mater. Chem. Front. 2, 497–504 (2018).

Kosaka, W., Liu, Z. & Miyasaka, H. Layered ferrimagnets constructed from charge-transferred paddlewheel [Ru2] units and TCNQ derivatives: the importance of interlayer translational distance in determining magnetic ground state. Dalton. Trans. 47, 11760–11768 (2018).

Miyasaka, H. et al. Stepwise neutral–ionic phase transitions in a covalently bonded donor/acceptor chain compound. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 5338–5345 (2011).

Nishio, M. & Miyasaka, H. Magnetic sponge phenomena associated with interchain dipole-dipole interactions in a series of ferrimagnetic chain compounds doped with minor diamagnetic species. Inorg. Chem. 53, 4716–4723 (2014).

Chikazumi, S Phyisics of Ferromagnetism. 2nd edn, (Oxford University Press: New York, 1997).

Kosaka, W. et al. Selective NO trapping in the pores of chain-type complex assemblies based on electronically activated paddlewheel-type [Ru2 II,II]/[Rh2 II,II] dimers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 18469–18480 (2013).

Gregg, S. J. & Sing, K. S. W. Adsorption, Surface Area And Porosity. (Academic Press, London, 1982).

Uyeda, C., Sugiyama, K. & Date, M. High field magnetization of solid oxygen. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 54, 1107–1114 (1985).

Kato, K. & Tanaka, H. Visualizing charge densities and electrostatic potentials in materials by synchrotron X-ray powder diffraction. Adv. Phys. X 1, 55–80 (2016).

Boudreaux, E. A. & Mulay, L. N. Theory and Applications of Molecular Paramagnetism. (John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1976).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA 3 for three-dimensional visualization of crystal, volumetric and morphology data. J. Appl. Cryst. 44, 1272–1276 (2011).

van der Sluis, P. & Spek, A. L. BYPASS: an effective method for the refinement of crystal structures containing disordered solvent regions. Acta Cryst. Sec. A 46, 194–201 (1990).

Favre-Nicolin, V. & Černý, R. FOX, ‘free objects for crystallography’: a modular approach to ab initio structure determination from powder diffraction. J. Appl. Cryst. 35, 734–743 (2002).

Izumi, F. & Momma, K. Three-dimensional visualization in powder diffraction. Solid State Phenom. 130, 15–20 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Hiroyasu Sato (Rigaku Co.Ltd.) for his help in structural determinations for the gas-accommodated compounds. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (Grant No. 16H02269, 15K13652, 26810029, and 18K05055), a Grand-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (‘π-System Figuration’ Area 2601, Grant No. 15H00983), and a Grand-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research (Grant No. 25000007) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology, Japan (MEXT), the E-IMR project, the Asahi Glass Foundation, Mitsubishi Foundation, and the Support Program for Interdisciplinary Research in Tohoku University. J.Z. is thankful for the JSPS Research Fellowship for Young Scientists (No. 17J02497). iCeMS is supported by the World Premier International Research Institutive (WPI) of MEXT.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.K. and H.M. formulated the project. Z.L. and J.Z. synthesized and characterized the compounds. W.K. performed the gas sorption measurements and the in situ study under gases in the magnetic studies, IR spectroscopy, and PXRD measurements with the refinement of structures. J.Z. performed SCXRD measurements under gases. Y.S. and A.H. conducted in situ PXRD measurements with the synchrotron radiation under gases under the supervision of S.K. and R.M.; W.K. and H.M. wrote the manuscript and all authors discussed the results and revised the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kosaka, W., Liu, Z., Zhang, J. et al. Gas-responsive porous magnet distinguishes the electron spin of molecular oxygen. Nat Commun 9, 5420 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07889-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-07889-1

This article is cited by

-

Selective sorption of oxygen and nitrous oxide by an electron donor-incorporated flexible coordination network

Communications Chemistry (2023)

-

Self-Healing, Self-Adhesive and Stable Organohydrogel-Based Stretchable Oxygen Sensor with High Performance at Room Temperature

Nano-Micro Letters (2022)

-

A metal–organic framework that exhibits CO2-induced transitions between paramagnetism and ferrimagnetism

Nature Chemistry (2021)

-

Magnetic ordering through itinerant ferromagnetism in a metal–organic framework

Nature Chemistry (2021)

-

Fabrication and characterization of epitaxial ferrimagnetic Mn3Ga thin films with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy

Emergent Materials (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.