Abstract

Purpose

The acquisition of pathogenic variants in the TERT promoter (TERTp) region is a mechanism of tumorigenesis. In nonmalignant diseases, TERTp variants have been reported only in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) due to germline variants in telomere biology genes.

Methods

We screened patients with a broad spectrum of telomeropathies (n = 136), their relatives (n = 52), and controls (n = 195) for TERTp variants using a customized massively parallel amplicon-based sequencing assay.

Results

Pathogenic −124 and −146 TERTp variants were identified in nine (7%) unrelated patients diagnosed with IPF (28%) or moderate aplastic anemia (4.6%); five of them also presented cirrhosis. Five (10%) relatives were also found with these variants, all harboring a pathogenic germline variant in telomere biology genes. TERTp clone selection did not associate with peripheral blood counts, telomere length, and response to danazol treatment. However, it was specific for patients with telomeropathies, more frequently co-occurring with TERT germline variants and associated with aging.

Conclusion

We extend the spectrum of nonmalignant diseases associated with pathogenic TERTp variants to marrow failure and liver disease due to inherited telomerase deficiency. Specificity of pathogenic TERTp variants for telomerase dysfunction may help to assess the pathogenicity of unclear constitutional variants in the telomere diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

The TERT gene encodes the catalytic component of the telomerase complex required to elongate telomeres in stem and progenitor cells.1,2 TERT is epigenetically silenced in normal somatic and nonproliferative cells, but aberrantly expressed in many human cancers.3,4,5,6 Acquisition of pathogenic TERT promoter (TERTp) variants located upstream of the translation initiation site at positions −124C>T (chr5:1,295,228), −146C>T (chr5:1,295,250), and −57A>C (chr5:1,295,161) has been described as a mechanism of tumorigenesis in cancer cells.3,6,7,8,9 These variants increase TERT expression and promote cell proliferation through recruitment of the transcription factor GABPA to the mutant allele.10,11,12 Somatic TERTp variant clones recently have been found in a few patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) caused by pathogenic germline variants in telomere biology genes. These pathogenic TERTp variants appear to functionally compensate the deleterious impact of disease-causing germline TERT variants by increasing telomerase activity and cell proliferation.13

Germline variants in telomere-related genes are etiologic in a broader spectrum of diseases collectively named telomere diseases or telomeropathies,14 including IPF but also affecting other organs, such as the bone marrow (aplastic anemia [AA] and dyskeratosis congenita [DC]) and the liver (cirrhosis and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis). We investigated the distribution of somatic pathogenic TERTp variants in a large cohort of patients with a spectrum of telomere diseases using a customized low-cost massively parallel sequencing assay optimized for identification and quantification of hematopoietic clones bearing the pathogenic −124 and −146 TERTp variants. We further assessed the association of these TERTp variants with telomere length (TL) and peripheral blood counts of patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cohort

In this retrospective study, we screened blood leukocytes from 136 patients with telomeropathies (median age, 29 years; range, 1–76), 52 relatives (median age, 40 years; range, 8–72), and 195 controls for the pathogenic −124 and −146 TERTp variants (Table 1). Patients were primarily diagnosed with DC (n = 21), AA (n = 86), IPF with or without another telomeropathy-related phenotypes (n = 18), or other phenotypes (n = 11; Supplementary Table S1). Clinical diagnosis of DC and AA was defined according to previous criteria.2,15,16 Briefly, DC patients had at least two of three manifestations of the clinical triad (dystrophic nails, patchy skin hyperpigmentation, and oral leukoplakia) and TL below the 1st percentile for age-matched controls, whereas AA patients presented with pancytopenia and hypocellular bone marrow without any evidence for myelodysplasia, myelofibrosis, or leukemia. Inclusion criteria were based on molecular diagnosis: TL below the 10th percentile of age-matched controls or a germline variant in a telomere biology gene classified as pathogenic, likely pathogenic, or variant of uncertain significance (VUS) by the Sherloc criteria, a framework that incorporates the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) criteria17,18 (Supplementary Tables S2–S3). The Sherloc criteria refined the ACMG guidelines to comprehensively assess variants’ pathogenicity based on both clinical and functional evidence, attributing points to score each variant for pathogenicity. The point score thresholds for pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants are four (4P) and five points (5P), respectively (Supplementary Table S4). Patients’ relatives were only studied if they harbored the same germline variant as the proband or had short telomeres, regardless of symptoms or evidence of disease. Enrolled individuals were seen in the Hematology Branch clinic of National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) or the bone marrow failure clinic in the Hospital das Clínicas, Ribeirão Preto School of Medicine, University of São Paulo (USP) between 2004 and 2017 (Supplementary Tables S2–S3). TL was measured by Southern blot (SB), quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), or flow fluorescent in situ hybridization (flow-FISH) according to protocols previously described.19 TL measurements by qPCR were confirmed by SB or flow-FISH at the time of this study. Patients with acquired immune AA (n = 70), IPF without evidence of inherited disease and a telomere-related germline pathogenic variant (n = 12), other inherited bone marrow failure syndromes (IBMFS; Diamond–Blackfan anemia, n = 4; chronic neutropenia, n = 3), and acute myeloid leukemia (AML; n = 106) were studied as controls (Supplementary Table S2-S3).

Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of NHLBI and from the Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa do Hospital das Clínicas de Ribeirão Preto. Samples were collected according to the Declaration of Helsinki and written consent was obtained from all participants or their legal guardians.

Massively parallel amplicon-based sequencing assay for detection of TERTp variants

We customized a massively parallel amplicon-based sequencing assay that targeted the TERTp region in which pathogenic −124 and −146 TERTp variants were located (Supplementary Figure S1). Although primers were not optimized to cover the −57A>C TERTp position, we also detected this variant in some of our samples. TERTp variant screening was performed in patients, relatives, and controls using peripheral blood leukocytes collected at the time of first clinical evaluation. Whenever possible, testing was also performed in granulocytes separated by gradient centrifugation in parallel with the respective leukocyte samples.

Library preparation consisted of two rounds of PCR to amplify the TERTp region. A first PCR was designed to amplify the targeted region and a second PCR for addition of Illumina adapters (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) into fragments. In the first PCR, we used a set of four different forward and reverse primers (total of eight primers) that were pooled in equimolar amounts to amplify the TERTp region (Supplementary Table S5). PCR products were then subjected to a second PCR round for the addition of the full i5/i7 Illumina adapter/index sequences into the DNA fragments.

Up to 96 libraries were pooled in equimolar amounts and pair-end sequenced in 300 cycles on the MiSeq platform (Illumina). Median coverage depth on targets was 104×. Reads were aligned to the human genome reference (hg19) using Burrows–Wheeler Aligner (BWA)20 and data quality was assessed using FastQC. Sequences were trimmed to remove the adapters as well as low-quality bases (-q 15 –minimum-length 35). Variants were called using VarDict and the following filtering criteria: -f 0.005 -v -c 1 -S 2 -E 3 -g 4 -th 8 (ref. 21). For comparison, we also used SAMTools22 and Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK)23 to call the variants. While VarDict called all TERTp variants that were further validated by droplet digital PCR (ddPCR; RainDance Technologies, Billerica, MA, USA), GATK and SAMTools only called variants with allele frequency >20% and >8%, respectively. Variants were annotated using Annovar24 and variant allele frequency (VAF) was calculated by a ratio of variant minor allele counts and total reads.

Droplet digital PCR

In samples that were available, the −124C>T and −146C>T TERTp variants identified by sequencing were validated by ddPCR (Supplementary Figure S2a), except for a single case that was confirmed by Sanger sequencing (Supplementary Figure S2b). TERTp variant clones were also tracked over time using this technique. In patient NIH46, the TERTp variant was quantified in the following blood cells’ subpopulations by ddPCR: leukocytes after whole-blood ammonium chloride potassium (ACK) lysis, granulocytes separated by gradient centrifugation using Ficoll–Hypaque, peripheral mononuclear cells separated by gradient centrifugation using Ficoll–Hypaque, CD14+CD16− monocytes, CD3+ T cells, and mononuclear fraction depleted for CD3+ and CD14+CD16-. The CD14+CD16- monocytes were isolated from mononuclear cells using immunomagnetic negative selection (the EasySep™ Human Monocyte Isolation kit, Stemcell Technologies, Cambridge, MA, USA) and CD3+ T cells were isolated from mononuclear cells by immunomagnetic positive selection (the EasySep™ Human CD3 Positive Selection kit II, Stemcell Technologies).

ddPCR was performed according to a protocol previously optimized with minor modifications to transfer the assay to the RainDance platform (RainDance).25 To evaluate the linearity and limit of detection of the ddPCR assay, a variant control sequence (CCCCTTCCGG) was serially diluted into 300 ng of sheared normal human genomic DNA to have an expected variant target copy number. A mean frequency abundance of the variant template was plotted versus the target copies input to generate a standard curve. Linearity of the assay was high (R2 = 0.99; Supplementary Figure S3a) and lower limit of detection was 0.17%. The highest mean frequency abundance obtained when genomic DNA from negative controls were used was 0.5%, and this value was used as the negative cut-off. The customized sequencing assay accurately detected pathogenic TERTp variants confirmed by ddPCR but did not identify false positives. The correlation between sequencing and ddPCR in quantification of TERTp variant clones was high (R2 = 0.97; Supplementary Figure S3b). Agreement between techniques was evaluated by Bland–Altman analysis, a statistical tool to compare clinical assays.26 Bland–Altman analysis evidenced a good agreement between these two methods (Supplementary Figure S3c), as the mean difference of VAF measurements was 0.95 and no measurements exceed the 95% confidence interval (CI) limits of agreement. The standard deviation (SD) between assays was 2.1 and 95% limits of agreement ranged from 5.15 to −3.25. Detailed protocols and primer sequences are available in Online Supplementary Data.

RESULTS

Pathogenic TERTp variants associated with different phenotypes from the spectrum of telomeropathies and patients’ ages

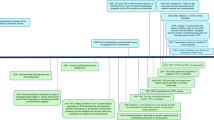

Of 136 cases, nine unrelated patients (7%; median age, 39 years; range, 24–65; Fig. 1) were found with TERTp variants. Nine patients had the pathogenic −124C>T variant, including two patients who also had the −57A>C TERTp variant (NIH37 and NIH93; Table 2). Patients were clinically diagnosed with IPF (5/18; 28%) and moderate AA (MAA; 4/86; 4.6%) (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Of note, eight of them also presented other phenotypes related to telomeropathies (Table 3); co-occurrence with cirrhosis and MAA was frequent (Tables 2–3). Five relatives (10%; median age, 63 years; range, 17–72) had the −124C>T (n = 4) or the −146C>T (n = 1) TERTp variants: three were asymptomatic and two were diagnosed with MAA or a DC-like phenotype. (Table 2). Within the same family, a somatic TERTp variant was not observed in more than one subject (Supplementary Figure S4), suggesting that acquisition of these variants was not due to a genetic susceptibility caused by the telomere-related germline pathogenic variant identified in the family.

Clinical association of somatic pathogenic TERT promoter (TERTp) variants and telomere diseases. Frequency of pathogenic TERTp variants in patients and relatives screened in the study. The size of the TERTp clone is represented by the variant allele frequency (VAF) and shown for each individual screened according to their primary diagnosis: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), moderate aplastic anemia (MAA), and relatives. Of 188 patients and relatives, 14 had the −124 or −146 TERTp variants (8%). An additional graph shows in detail the pathogenic TERTp clone size, initial diagnosis, and the telomere biology gene in which a germline variant was identified from the patients/relatives with pathogenic TERTp variants. Four relatives were asymptomatic.

The frequency of pathogenic TERTp variants was much higher in IPF patients compared with AA cases (28% vs. 4.6%; Fisher’s exact test, P = 0.007; Table 1). Because some patients presented different phenotypes from the spectrum of telomeropathies, we then investigated whether pathogenic TERTp variants were more frequent in the setting of pulmonary disease compared with marrow failure or liver disease. No difference in frequency of disease phenotypes (IPF vs. marrow failure or liver disease) was observed among patients with a pathogenic TERTp variant (36% vs. 50% or 42%, respectively; χ2 test, P > 0.05; Table 3), suggesting that these variants occurred in all these clinical presentations. Pathogenic TERTp variant clones positively correlated with age, as they were only present in individuals older than 18 years old and more frequent in those 60 to 80 years old (Fig. 2a). Six of 86 individuals ranging in age from 21 to 40 (7%), 3 of 44 individuals ranging in age from 41 to 60 years (6.8%), and 5 of 18 patients older than 61 years (27.8%) had pathogenic TERTp variants. The median age of patients with TERTp variants and a primary diagnosis of IPF and MAA was 57 and 27 years, respectively.

Molecular and clinical characteristics of individuals with pathogenic TERT promoter (TERTp) variants. (a) Frequency of pathogenic TERTp variants in the different groups classified by age range. Pathogenic TERTp variant frequency increased with aging. (b) The −124C>T TERTp variant allele frequency (VAF) in blood cells’ subpopulations from patient NIH46 quantified by droplet digital PCR (ddPCR). (c) Chronological pathogenic TERTp variant dynamics detected by ddPCR. In serial samples, clones bearing the −146C>T or −124C>T pathogenic TERTp variants expanded over time for all patients evaluated. (d) Chronological analysis of the pathogenic TERTp VAF and hematologic blood counts from two patients during danazol treatment. During the androgen therapy, TERTp clone sizes decreased in both total leukocytes and granulocytes as blood counts improved, especially the platelet counts and hemoglobin levels. A blue bar represents the time frame in which patients were under the danazol treatment. Pathogenic TERTp clones were tracked by ddPCR and dashed lines represent the lower limit of detection (0.5%) of this technique. Hb hemoglobin, WBC white blood cell count.

Pathogenic TERTp variants were found in telomeropathy patients who had a germline variant in telomere biology genes but not in controls (median age, 29 years; range, 1–88) or in patients with very short telomeres without a germline variant in telomere biology genes (median age, 25 years; range, 5–63; Table 1). We also confirmed the absence of pathogenic TERTp variants in the granulocytic fractions from controls in which materials were available (Supplementary Table S2–S3).

Pathogenic TERTp variants more frequently co-occurred with germline TERT variants in myeloid cells

The customized sequencing assay detected pathogenic TERTp clones at VAF as low as 1.2%, which was confirmed by ddPCR. Overall, TERTp clones were more frequent in individuals with germline TERT variants (12/14 cases); only two patients harbored a germline variant in TERC. The germline variants identified in telomere biology genes were classified as pathogenic or likely pathogenic (n = 8), and VUS (n = 6; Table 2) and, except for the TERT R696C found in USP26, they were heterozygous. All variants classified as VUS had some evidence for being pathogenic (all had a Sherloc score of 3.5P) but insufficient to meet Sherloc criteria for pathogenicity; all were predicted as deleterious in silico, absent in control populations, and associated with a family history and phenotype of telomere diseases (Supplementary Table S4).

Pathogenic TERTp variant clone sizes varied from 1.2% to 50% in total leukocytes and clones were found at higher allele frequencies in the granulocytic fractions in four patients (Table 2 and Fig. 2b). In NIH93, the −124C>T TERTp was identified in total leukocytes and granulocytes by both sequencing and ddPCR at VAF as low as 6%. However, in NIH61, pathogenic TERTp clones were only detected in granulocytes by sequencing due to very low VAF in total leukocytes. Results were similar when peripheral blood cell subpopulations from NIH46 were separated by magnetic selection for screening of the −124C>T TERTp variant by ddPCR. The −124C>T TERTp variant was found enriched in the granulocyte fraction and mononuclear cells depleted for CD3+ and CD14+ cells (Fig. 2b). Clonal dominance was not observed in most individuals with pathogenic TERTp variants; nine had pathogenic TERTp clones at VAF lower than 10%.

Pathogenic TERTp variant clones expanded over time but did not associate with telomere elongation or response to danazol treatment

The clonal dynamics of pathogenic TERTp variants were assessed in serial samples from five patients over a period as long as four years; three had a pathogenic or likely pathogenic germline variant, and two had a germline VUS. In all cases, the TERTp variant clone size expanded over time (Fig. 2c), suggesting a selective growth advantage in comparison with unmutated hematopoietic cells.

Pathogenic TERTp variants were not associated with changes in patients’ TLs or improvement in blood counts; most subjects with a pathogenic TERTp variant, which is known to upregulate TERT expression, nevertheless had short or very short telomeres (12/14 individuals). Two individuals presented with normal TL (NIH98 and USP26). Despite her normal TLs, NIH98 had short 3’ overhangs as previously reported.27

Twenty-one patients and three relatives from the cohort were enrolled in a clinical trial for treatment with danazol for two years (Supplementary Table S3) (ref.16). Five had pathogenic TERTp variant clones at diagnosis; three were responders and two were off-study after 3–6 months (Table 2). NIH93 and NIH61 achieved a hematologic response at 3 months of treatment and NIH46 showed a response at 6 months. In these patients, an average size of pathogenic TERTp clone in myeloid cells was 4%, except for NIH46 who had a clone of 21%. Patients NIH31 and NIH37 responded to danazol at 3 months of treatment but were withdrawn from the study due to organ complications not involving the marrow. NIH31 had a large pathogenic TERTp variant clone (VAF of 50%) and NIH37 had two different variants at VAFs <5% (Table 2).

Chronological analysis of pathogenic TERTp variants during androgen treatment was assessed using serial samples that were available for NIH46 and NIH61 (Fig. 2d). In both, the size of pathogenic TERTp clones decreased during danazol treatment while blood counts improved. After treatment, the VAF of these pathogenic TERTp variant clones increased. These data suggest that hematologic response observed in these patients was mostly attributed to danazol and not to the presence of pathogenic TERTp variants, which appeared diluted in peripheral blood by treatment response. Indeed, pathogenic TERTp variants did not predict response to danazol, because patients with and without these somatic variants responded to treatment at 3–6 months and were not off-study (with TERTp variants vs. without TERTp variants, 3/5 vs. 8/12; Fisher’s exact test, P > 0.5).

DISCUSSION

We have expanded the spectrum of nonmalignant diseases associated with pathogenic TERTp variants to MAA and cirrhosis. Our data indicated that the emergence of pathogenic TERTp variants correlates with chronologic aging and may be clonal evidence of a telomere disease in 8% of patients and relatives presenting these clinical phenotypes.

Pathogenic TERTp variants have been reported only in cancer or IPF but are rare in hematologic malignancies.4,5 Indeed, we did not find these variants in 106 AML patients screened by our sequencing assay. Lack of association between pathogenic TERTp activation and hematologic diseases has been attributed to constitutively high TERT expression in hematopoietic stem cells.4,12 Consistent with this hypothesis, clones bearing pathogenic TERTp variants in our study were positively selected in the bone marrow when patients had an inherited telomerase deficiency. No pathogenic TERTp variants were found in our control group or previously reported cohorts including more than 2,500 healthy subjects (mean age of 50 ± 11 years) and 132 elderly individuals (range, 98–108 years).13

Germline pathogenic variants in 12 genes that impair telomere biology have been linked to telomere diseases.14 TL measurement and genetic screening have been used for differential diagnosis of telomeropathies. Both commercial and in-house targeting sequencing panels are preferred due to lower cost and a known subset of genes recurrently mutated in these diseases. However, an accurate interpretation of genetic testing is often complicated by the heterogeneity in telomere diseases’ penetrance and presentation. In this work, seven patients had a germline VUS; all were novel and found in TERT and TERC genes, both commonly mutated genes in telomere diseases and not tolerable to either missense or loss-of-function variants according to ExAC metrics (http://exac.broadinstitute.org/). Despite the strong clinical evidence, the identified VUS did not meet criteria for pathogenicity using either ACMG or Sherloc classifications due to lack of segregation data and specific functional assays. Specificity of pathogenic TERTp variants for telomerase dysfunction may be additional evidence for pathogenicity of germline VUS and may help identify patients with telomeropathies that lack classical phenotypes.

In cancer cells, current models propose that pathogenic TERTp acquisition only occurs in cells with very short telomeres due to selective pressure for cell immortalization.6,28,29,30 However, two of our patients with pathogenic TERTp variants had normal TLs (NIH98 and USP41) in which the germline TERT variant pathogenicity is supported by eroded 3’ overhangs, functional assays, and segregation data.27,31 We did not observe longer TL in patients with pathogenic TERTp variants nor telomere elongation in screened serial samples. In agreement with our findings is the report that TERT upregulation driven by TERTp pathogenic variants does not prevent telomere erosion but rather sustains cell proliferation.29 Also, a pathogenic TERTp variant increased cell proliferation and telomerase activity in Epstein–Barr virus (EBV)-transformed lymphoblastoid cells derived from an IPF patient despite his very short telomeres.13 In fibroblasts from DC patients, TERT expression prevents premature senescence and extends cells' proliferative lifespan but is insufficient to maintain TL.32,33 In different cancers, TERT reactivation has not been widely associated with telomere elongation but rather with sustained proliferative capacity.8,34,35

The TERTp variant most commonly identified in our cohort was the pathogenic -124C>T (C228T) variant. However, we found rare −124 (n = 2) and −146 (n = 1) TERTp variants with a C>A transition instead of the frequently found C>T substitution in two DC patients (NIH39 and USP02) and one IPF patient (NIH34; Supplementary Figure S5). The two DC patients harbored pathogenic germline variants in RTEL1 or DKC1 whereas the IPF patient harbored a germline VUS in TERT. The −124 C>A also creates a putative ETS motif11,36 and has been previously observed in melanoma and meningioma.36,37 The −146 C>A has been previously found in a single case of thyroid cancer38 but fails to increase TERT expression in luciferase reporter assays and does not create a novel ETS motif.11 Even though these variants have been reported in other studies, the −124C>A and −146C>A variants identified by our sequencing assay could be artifacts because they were not validated by either ddPCR or Sanger sequencing: the ddPCR probes were specific for the C>T transition; clones were very small to be detected by Sanger; and amounts of patients’ samples were limited.

In our study, the frequency of pathogenic TERTp variants in IPF patients was higher than previously observed in a cohort of 200 IPF patients with heterozygous germline variants in TERT, TERC, PARN, or RTEL1 (28% vs. 5%) (ref.13). This difference may be explained by the distinct methodologies used to detect the TERTp variants. Our customized amplicon-based sequencing assay detected clones as small as 1.2% VAF, as opposed to Sanger sequencing, which detects clones at VAF of 20% or higher. Also, our IPF cohort was relatively small (n = 18).

Our study has limitations. First, we did not evaluate whether pathogenic TERTp variants were in cis or trans to the wild-type allele due to insufficiency of clinical samples. Although these somatic variants have been described preferentially in cis with the wild-type allele,13 one of our patients with a homozygous pathogenic TERT germline variant also harbored the pathogenic −124 TERTp variant that was not associated with clinical worsening. Lack of serial and myeloid cell–enriched samples also hampered analysis of TERTp variant clones’ chronological dynamics and detection of pathogenic TERTp variants at low allele frequency in leukocytes. Second, the natural history of these variants in telomeropathies and the clonal dynamics under androgen treatment need to be assessed by functional studies. Nevertheless, the mechanism for TERT reactivation by androgens appears to be different from pathogenic TERTp variants, because the hormone does not bind to the region in which the somatic TERTp variants are located.10,39 Based on our preliminary results, cells without pathogenic TERTp variants may be more responsive to danazol compared with pathogenic TERTp variant clones, which would lead to a dilution of TERTp variant clones during treatment. Also, these variants may not affect patients’ responses to androgen therapy, because patients responded to treatment regardless of pathogenic TERTp clones.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that pathogenic TERTp clones were positively selected in nonmalignant diseases, in the setting of telomerase-deficiency bone marrow cells. TERTp clones’ selection appeared to be age-dependent and random, and clones might be selected as an attempt to restore telomerase activity in patients with telomere diseases. Pathogenic TERTp variants may be good evidence of an inherited bone marrow failure driven by telomerase impairment; although these somatic variants have been found in only 8% patients and relatives, the addition of TERTp region in targeted panels may further support the pathogenic role of germline variants identified in telomere biology genes.

References

Greider CW, Blackburn EH. Identification of a specific telomere terminal transferase activity in Tetrahymena extracts. Cell. 1985;43 2 Pt 1:405–413.

Calado RT, Young NS. Telomere diseases. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2353–2365.

Kim NW, Piatyszek MA, Prowse KR, et al. Specific association of human telomerase activity with immortal cells and cancer. Science. 1994;266:2011–2015.

Killela PJ, Reitman ZJ, Jiao Y, et al. TERT promoter mutations occur frequently in gliomas and a subset of tumors derived from cells with low rates of self-renewal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:6021–6026.

Panero J, Alves-Paiva RM, Roisman A, et al. Acquired TERT promoter mutations stimulate TERT transcription in mantle cell lymphoma. Am J Hematol. 2016;91:481–485.

Bell RJ, Rube HT, Xavier-Magalhães A, et al. Understanding TERT promoter mutations: a common path to immortality. Mol Cancer Res. 2016;14:315–323.

Scott GA, Laughlin TS, Rothberg PG. Mutations of the TERT promoter are common in basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2014;27:516–523.

Heidenreich B, Rachakonda PS, Hosen I, et al. TERT promoter mutations and telomere length in adult malignant gliomas and recurrences. Oncotarget. 2015;6:10617–10633.

Horn S, Figl A, Rachakonda PS, et al. TERT promoter mutations in familial and sporadic melanoma. Science. 2013;339:959–961.

Akıncılar SC, Khattar E, Boon PL, Unal B, Fullwood MJ, Tergaonkar V. Long-range chromatin interactions drive mutant TERT promoter activation. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:1276–1291.

Bell RJ, Rube HT, Kreig A, et al. Cancer. The transcription factor GABP selectively binds and activates the mutant TERT promoter in cancer. Science. 2015;348:1036–1039.

Chiba K, Johnson JZ, Vogan JM, Wagner T, Boyle JM, Hockemeyer D Cancer-associated TERT promoter mutations abrogate telomerase silencing. eLife 2015; 4: e07918. 2015 July 21; https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.07918. [Epub ahead of print].

Maryoung L, Yue Y, Young A, et al. Somatic mutations in telomerase promoter counterbalance germline loss-of-function mutations. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:982–986.

Townsley DM, Dumitriu B, Young NS. Bone marrow failure and the telomeropathies. Blood. 2014;124:2775–2783.

Young NS. Current concepts in the pathophysiology and treatment of aplastic anemia. Hematol Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2013;2013:76–81.

Townsley DM, Dumitriu B, Liu D, et al. Danazol treatment for telomere diseases. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:1095–1096.

Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–424.

Nykamp K, Anderson M, Powers M, et al. Sherloc: a comprehensive refinement of the ACMG-AMP variant classification criteria. Genet Med. 2017;19:1105–1117.

Gutierrez-Rodrigues F, Santana-Lemos BA, Scheucher PS, Alves-Paiva RM, Calado RT. Direct comparison of flow-FISH and qPCR as diagnostic tests for telomere length measurement in humans. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e113747.

Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760.

Lai Z, Markovets A, Ahdesmaki M, et al. VarDict: a novel and versatile variant caller for next-generation sequencing in cancer research. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:e108.

Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079.

McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303.

Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:e164.

McEvoy AC, Calapre L, Pereira MR, et al. Sensitive droplet digital PCR method for detection of TERT promoter mutations in cell free DNA from patients with metastatic melanoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8:78890–78900.

Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–310.

Marsh JCW, Gutierrez-Rodrigues F, Cooper J, et al. Heterozygous RTEL1 variants in bone marrow failure and myeloid neoplasms. Blood Adv. 2018;2:36–48.

Khattar E, Kumar P, Liu CY, et al. Telomerase reverse transcriptase promotes cancer cell proliferation by augmenting tRNA expression. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:4045–4060.

Chiba K, Lorbeer FK, Shain AH, et al. Mutations in the promoter of the telomerase gene TERT contribute to tumorigenesis by a two-step mechanism. Science. 2017;357:1416–1420.

Heidenreich B, Kumar R. TERT promoter mutations in telomere biology. Mutat Res. 2017;771:15–31.

Tsakiri KD, Cronkhite JT, Kuan PJ, et al. Adult-onset pulmonary fibrosis caused by mutations in telomerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:7552–7557.

Westin ER, Chavez E, Lee KM, et al. Telomere restoration and extension of proliferative lifespan in dyskeratosis congenita fibroblasts. Aging Cell. 2007;6:383–394.

Wong JM, Collins K. Telomerase RNA level limits telomere maintenance in X-linked dyskeratosis congenita. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2848–2858.

Liu T, Wang N, Cao J, et al. The age- and shorter telomere-dependent TERT promoter mutation in follicular thyroid cell-derived carcinomas. Oncogene. 2014;33:4978–4984.

Hosen I, Rachakonda PS, Heidenreich B, et al. Mutations in TERT promoter and FGFR3 and telomere length in bladder cancer. Int J Cancer. 2015;137:1621–1629.

Spiegl-Kreinecker S, Lötsch D, Neumayer K, et al. TERT promoter mutations are associated with poor prognosis and cell immortalization in meningioma. Neuro Oncol. 2018; 20:1584–1593.

Heidenreich B, Nagore E, Rachakonda PS, et al. Telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter mutations in primary cutaneous melanoma. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3401.

Bae JS, Kim Y, Jeon S, et al. Clinical utility of TERT promoter mutations and ALK rearrangement in thyroid cancer patients with a high prevalence of the BRAF V600E mutation. Diagn Pathol. 2016;11:21.

Calado RT, Yewdell WT, Wilkerson KL, et al. Sex hormones, acting on the TERT gene, increase telomerase activity in human primary hematopoietic cells. Blood. 2009;114:2236–2243.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Olga Rios for assistance in obtaining patients’ samples, Valentina Giudice and Zhijie Wu for their advice and helpful discussion, the Bioinformatics and Computational Core Facility at the NHLBI for data analysis, and the DNA sequencing and Genomics Core Facility at NHLBI. This work was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/NIH, and by the Coordination of Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES) and the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP); grants 2014/27294-7, 2015/19074-0, and 2013/08135-2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. If you remix, transform, or build upon this article or a part thereof, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gutierrez-Rodrigues, F., Donaires, F.S., Pinto, A. et al. Pathogenic TERT promoter variants in telomere diseases. Genet Med 21, 1594–1602 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-018-0385-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-018-0385-x

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Adaptive and Maladaptive Clonal Hematopoiesis in Telomere Biology Disorders

Current Hematologic Malignancy Reports (2024)

-

Genetics of human telomere biology disorders

Nature Reviews Genetics (2023)

-

Clonal Hematopoiesis and Myeloid Neoplasms in the Context of Telomere Biology Disorders

Current Hematologic Malignancy Reports (2022)

-

Activating somatic and germline TERT promoter variants in myeloid malignancies

Leukemia (2021)

-

Somatic genetic rescue of a germline ribosome assembly defect

Nature Communications (2021)