Abstract

We establish autosomal recessive DES variants p.(Leu190Pro) and a deep intronic splice variant causing inclusion of a frameshift-inducing artificial exon/intronic fragment, as the likely cause of myopathy with cardiac involvement in female siblings. Both sisters presented in their twenties with slowly progressive limb girdle weakness, severe systolic dysfunction, and progressive, severe respiratory weakness. Desmin is an intermediate filament protein typically associated with autosomal dominant myofibrillar myopathy with cardiac involvement. However a few rare cases of autosomal recessive desminopathy are reported. In this family, a paternal missense p.(Leu190Pro) variant was viewed unlikely to be causative of autosomal dominant desminopathy, as the father and brothers carrying this variant were clinically unaffected. Clinical fit with a DES-related myopathy encouraged closer scrutiny of all DES variants, identifying a maternal deep intronic variant within intron-7, predicted to create a cryptic splice site, which segregated with disease. RNA sequencing and studies of muscle cDNA confirmed the deep intronic variant caused aberrant splicing of an artificial exon/intronic fragment into maternal DES mRNA transcripts, encoding a premature termination codon, and potently activating nonsense-mediate decay (92% paternal DES transcripts, 8% maternal). Western blot showed 60–75% reduction in desmin levels, likely comprised only of missense p.(Leu190Pro) desmin. Biopsy showed fibre size variation with increased central nuclei. Electron microscopy showed extensive myofibrillar disarray, duplication of the basal lamina, but no inclusions or aggregates. This study expands the phenotypic spectrum of recessive DES cardio/myopathy, and emphasizes the continuing importance of muscle biopsy for functional genomics pursuit of ‘tricky’ variants in neuromuscular conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Desmin is an intermediate filament protein expressed in cardiac, skeletal and smooth muscle. Desminopathies, are typically caused by autosomal dominant mutations in DES [1] and are clinically heterogeneous [2]. Desminopathy may manifest as myopathy, typically with adult onset (OMIM #601419), cardiomyopathy (OMIM #604765), cardiac conduction defects, arrhythmias; or a combination of these features. Respiratory problems are also common [2]. DES variants are a common cause of myofibrillar myopathy [2]; characterised by myofibrillar disarray, granulofilamentous inclusions on muscle pathology and desmin-containing protein aggregates by immunohistochemistry.

DES variants are most commonly autosomal dominant or de novo dominant missense mutations [1,2,3]. Among DES missense variants, the most common amino acid substitution is to a proline, as this disrupts helix formation in the rod domain of desmin [3]. Data-mining of all DES variants classified in ClinVar as pathogenic or likely pathogenic, or classified as disease-causing in the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD; see Supplemental Table 1) identified only seven splice site variants (and see also [3]), with a synonymous and missense variant affecting the last nucleotide of exon 3 predicted to disrupt splicing. No deep intronic variants in DES have yet been identified in an individual affected with suspected desminopathy, which disrupt the production or function of desmin protein due to splicing aberrations; in this case, inclusion of an artificial exon/intronic fragment encoding a premature stop codon and subject to mRNA silencing by nonsense-mediated decay.

A few rare cases of autosomal recessive desminopathy have been described [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11], ranging from severe infantile to adult-onset, with variable phenotypic presentations affecting skeletal, cardiac and smooth muscle (Table 1; extended descriptions of clinical and histopathological phenotypes are provided within Supplemental Table 2).

Methods

This study was approved by the SCHN human ethics committee 10/CHW/45 with informed, written consent. Genomic sequencing was performed on gDNA extracted from blood as described [12, 13]. PCR-free whole genome sequencing was performed at the Broad Institute of Harvard and MIT. Samples were prepared utilizing custom next generation sequencing index adaptors (Integrated DNA Technologies, Iowa, 52241, USA) and Kapa Biosciences HyperPrep library construction kit and sequenced on an Illumina HiSeqX v1 (2 × 150 bp reads). Data processing included read de-multiplexing, aggregation, alignment (Burrows-Wheeler Aligner: Bwa-Mem) with 30 × mean coverage. Segregation analysis of DES variants was performed by Sanger sequencing. RNA isolated from 30 × 8 µm muscle cryosections (10 mm2 surface area) was used for RNA sequencing and RT-PCR [13]. cDNA was synthesised from 1 µg of total skeletal muscle RNA [14] and PCR performed using Immolase DNA polymerase (Bioline, NSW, Australia). Western blotting [15] and immunohistochemistry [16] were performed as described. Antibodies: anti-desmin NCL-L-Des-DerII, anti-myotilin NCL-myotilin (Leica Biosystems, VIC, Australia); anti-mouse IgG light chain and anti-rabbit HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (GE healthcare, NSW, Australia); Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, PA, USA).

Case report

Clinical history

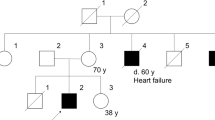

The proband (II:3) and her affected older sister (II:2), born to non-consanguineous Italian parents (Fig. 1ai), presented in their mid to late 20’s with limb-girdle pattern of muscle weakness and elevated serum creatine kinase (up to 1070 U/L; reference range 0–175 U/L). Both sisters had normal developmental milestones and academic performance. The weakness was slowly progressive, and associated with cardiomyopathy and respiratory weakness. Echocardiogram in II:3 showed severe systolic dysfunction requiring a defibrillator insertion, with an ejection fraction of 15%, dilated left ventricle (LV) and prolonged QRS trace (Fig. 1aii). A skeletal muscle biopsy from II:3 was performed at the age of 27 years that showed dystrophic changes, with variation in fibre size, scattered necrotic fibers and an increase in central nuclei (Fig. 1aiii); oxidative stains were normal. Electron microscopy showed extensive myofibrillar disarray, reduplication of basal lamina, no inclusions or granulofilamentous aggregates (Fig. 1b). By the age of 34 years, II:3 developed respiratory weakness requiring continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), and by the age of 43 years, became dependent on use of a wheelchair. Her older sister II:2 showed a somewhat less severe clinical course; presenting with progressive limb-girdle weakness with cardiac involvement at the age of 29 years, requiring use of a wheelchair at 45 years of age. II:2 has not required insertion of a defibrillator, or any respiratory support to date.

a (i) Family pedigree showing inheritance of recessive DES variants. (ii) Echocardiogram for Patient II:3 showing severe end diastolic (normal LVIDd < 5.3 cm) dilatation and intraventricular conduction delay on ECG. (iii) Histology haemotoxylin and eosin stain of frozen skeletal deltoid muscle from II:3 demonstrating increased internal nuclei, variation in fibre size, scattered necrotic fibres and nuclear clumps. b Electron microscopy of Patient II:3. (i) Myofibrillar loss and disarray, and an internalised nucleus. Scale bar 5 µm. (ii) Longitudinal orientation showing misalignment of sarcomeres and variation in myofibril thickness. Scale bar 5 µm. (iii) Higher magnification images showing disorganisation of myofibrils lying at divergent angles. Scale bar 2 µm. (iv) Multiple layers of reduplicated basal lamina. Scale bar 2 µm. c (i) Western blot loading decreasing amounts of Control or Patient II:3 skeletal muscle lysate showing a reduction in levels of desmin in II:3, with no change in levels of myotilin, actinin or actin (myofibrillar protein controls). (ii) Immunohistochemistry of frozen muscle sections stained with NCL-spectrin as a marker of sarcolemmal integrity and NCL-desmin. Variable intensity cytoplasmic staining was observed for desmin compared to uniform cytoplasmic staining in control

Targeted gene sequencing of CNBP, LMNA, FHL1, FKRP and CAPN3 was normal, and exome sequencing failed to identify the genetic cause (N.B. the DES c.569 T > C, p.(Leu190Pro) variant was not identified due to poor coverage in the region).

Genomic sequencing results

Whole genome sequencing identified compound heterozygous variants in DES in the affected sisters (Figs. 1a and 2b): a paternal missense variant Chr2(GRCh37):g.220283753 T > C, NM_001927.3, c.569 T > C, p.(Leu190Pro), also inherited by the two unaffected brothers; and maternal deep intronic variant NG_008043.1, g.220289644 G > A, NM_001927.3 c.1289-741 G > A. Neither DES variant is present in the gnomAD database. Variants have been submitted to the gene variant database at www.LOVD.nl/DES (variant IDs 0000446054, 0000446055).

a Disparate patterns of mRNA expression levels from DES alleles. (i) Schematic representation of allelic percentages derived from RNA-seq read depth. The paternal g.220283753 T > C, c.569 T > C variant shows allele bias, accounting for 92% of RNA-seq reads. Three other common SNPs in the coding region also show allele bias, with the reference sequence present in 92% of reads. Inheritance of these SNPs could not be determined; although allele bias data infers maternal inheritance. No splicing aberrations were observed to result from these common SNPs. (ii) Screenshot showing the RNA sequencing reads over the paternal missense c.569 T > C variant and substantial allele bias of variant C nucleotide. b Schematic representation of DES exon structure and consequence of the DES intronic variant c.1289-741 G > A, r.1288_1289ins1289-739_1289-622 (118 bp artificial exon/intronic fragment and abnormal termination codon). Enlarged representation of the artificial exon/intronic fragment and flanking essential splice sites. Predicted strengths of the splice donor and accepter using Alamut Visual® Interactive Biosoftware are annotated beneath. C: cDNA sequencing electropherogram of a RT-PCR amplicon showing inclusion of the 118 nt artificial exon/intronic fragment into the DES mRNA, flanked by exon 7 and exon 8 sequences

The missense p.(Leu190Pro) lies in the rod domain of desmin, and is predicted to be damaging (Polyphen2: 0.997, probably damaging, Mutationtaster: disease causing, FATHMM: damaging, CADD-PHRED: 24.9, SIFT: 0, deleterious, and Align GVGD: Class C65). Sanger-sequencing confirmed segregation in the father and two unaffected brothers (Fig. 1ai). Thus, the missense variant p.(Leu190Pro) was viewed as unlikely to be causative of an autosomal dominant desminopathy. However, suspicion of a DES-related cardio/myopathy was alerted. Despite absence of biopsy findings consistent with myofibrillar myopathy, closer scrutiny was applied to all variants affecting the DES locus. A maternal deep intronic variant c.1289-741 G > A was identified in the two affected siblings; absent in the two unaffected brothers. c.1289-741 G > A was predicted to create a cryptic acceptor site by all five splicing prediction programs in Alamut Visual (Interactive Biosoftware, Rouen, France) (Fig. 2b).

mRNA studies confirm splice-altering effects of the deep intronic variant

RNA sequencing using muscle biopsy specimens from the proband II:3 showed significant allele bias among DES transcripts for 3 heterozygous single-nucleotide variants spanning the DES gene (Fig. 2a). With the c.569 T > C, p.(Leu190Pro) variant specific for paternal transcript, collective data infer paternal transcripts account for 92% of the DES mRNA pool, with 8% maternal transcripts (Fig. 2a). RNA sequencing also showed ~ 100 reads immediately following the c.1289-741 G > A variant creating a cryptic splice acceptor, which may correspond to inclusion of a 118 nucleotide (nt) artificial exon/intronic fragment into the DES mRNA, inducing a frameshift, p.Thr431Serfs*43 (data not shown). DES allele bias of this nature is consistent with active nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) of the maternal allele due to the frameshift induced by inclusion of the 118 nt artificial exon/intronic fragment. We were unable to confirm precisely inclusion of the pseudo-exon by RNA sequencing, due to the combination of effective nonsense-mediated decay silencing this allele, and, technical limitations of short-read RNA sequencing that do not effectively bridge multiple exons.

Therefore, RT-PCR was performed on cDNA derived from a skeletal muscle biopsy from II:3, using forward and reverse primers within the predicted intron 7 118 nt fragment, paired with primers in exon 5 or exon 9. PCR amplicons corresponding to an aberrantly spliced product incorporating the artificial exon/intronic fragment into DES transcripts were observed for the proband; absent from two control muscle cDNA specimens. Sanger sequencing of amplified products confirmed the presence of a 118 nt artificial exon/intronic fragment in DES mRNA transcripts from II:3, r.1288_1289ins1289-739_1289-622 (Fig. 2b, c).

Western blot reveals 60–75% reduction in desmin levels, likely comprised only of missense p.Leu190Pro desmin

Western blot was performed on skeletal muscle lysate from the proband and an aged matched control. A standard curve demonstrates that desmin protein levels in the proband are reduced, approximately one-quarter to one-third the levels of the control, while myotilin levels are unchanged. α-actinin and actin show appropriate loading for the standard curve (Fig. 1c).

Discussion

In summary, we show compound heterozygosity for a missense p.(Leu190Pro) DES variant and deep intron-7 cryptic splice variant are the likely cause of recessive DES myopathy with severe cardiomyopathy in two siblings. RNA-seq and RT-PCR studies of muscle-derived mRNA confirms the c.1289-741 G > A variant induces abnormal inclusion of a 118 nt artificial exon/intronic fragment, r.1288_1289ins1289-739_1289-622; effecting a frameshift, abnormal stop codon, and nonsense-mediated decay of maternal transcripts. Therefore, the pool of DES mRNA in skeletal muscle is comprised largely of paternal transcripts encoding the p.(Leu190Pro) missense variant; predicted by in silico tools to be deleterious or damaging. The p.(Leu190Pro) substitution occurs in the coil 1B domain of desmin involved in homodimerisation. Many pathogenic missense mutations in DES introduce prolines into coil domains [3]. Proline residues induce a kink in polypeptide chains, which, in the setting of an α-helix are disruptive; distorting secondary structure, with proline residues unable to form hydrogen bonding required for α-helix stability. Likely pathogenicity of identified recessive DES variants is supported by western analyses, showing desmin protein levels are reduced to around one-quarter to one-third levels in control muscle. As desmin levels are less than one-half that observed in controls, data also suggests inherent instability and/or elevated turnover of the missense p.(Leu190Pro) desmin. Desmin deficiency in this case of autosomal recessive desminopathy is a feature distinct from autosomal dominant desminopathy, where levels of desmin can often appear elevated due to desmin aggregates [17].

Our results extend the phenotypic spectrum of recessive desminopathy. In contrast to severe infantile presentation associated with homozygous loss-of-function DES variants [18], our two affected siblings presented in their late teens to early twenties with a limb girdle pattern of progressive weakness and cardiomyopathy, expressing diminished levels of variant p.(Leu190Pro) desmin. Muscle biopsy showed extensive myofibrillar disarray, but did not show aggregates typical of DES myofibrillar myopathy (aggregates were also not present in AR desminopathy described in [5, 11]). Thus, recessive desminopathy may take different forms depending whether characterised by desmin deficiency, or (reduced) expression levels of different missense forms of desmin protein, that each may elicit different impacts on intermediate filament structure and function. Our results show that many tricky diagnoses in neuromuscular conditions depend upon analyses of available muscle biopsy specimens, combined with interdisciplinary clinical, pathological and functional genomics expertise. Importantly, deep intronic variants inducing inclusion of a frameshifting artificial exon (intronic sequences) make very attractive candidates for morpholino-based genetic exon-skipping therapies, currently advancing through therapeutic pipelines.

References

Goldfarb LG, Olive M, Vicart P, Goebel HH. Intermediate filament diseases: desminopathy. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;642:131–64.

Clemen CS, Herrmann H, Strelkov SV, Schroder R. Desminopathies: pathology and mechanisms. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;125:47–75.

Brodehl A, Gaertner-Rommel A, Milting H. Molecular insights into cardiomyopathies associated with desmin (DES) mutations. Biophys Rev. 2018;10:983–1006.

Arbustini E, Pasotti M, Pilotto A, Pellegrini C, Grasso M, Previtali S, et al. Desmin accumulation restrictive cardiomyopathy and atrioventricular block associated with desmin gene defects. Eur J Heart Fail. 2006;8:477–83.

Cetin N, Balci-Hayta B, Gundesli H, Korkusuz P, Purali N, Talim B, et al. A novel desmin mutation leading to autosomal recessive limb-girdle muscular dystrophy: distinct histopathological outcomes compared with desminopathies. J Med Genet. 2013;50:437–43.

Goldfarb LG, Park KY, Cervenakova L, Gorokhova S, Lee HS, Vasconcelos O, et al. Missense mutations in desmin associated with familial cardiac and skeletal myopathy. Nat Genet. 1998;19:402–3.

McLaughlin HM, Kelly MA, Hawley PP, Darras BT, Funke B, Picker J. Compound heterozygosity of predicted loss-of-function DES variants in a family with recessive desminopathy. BMC Med Genet. 2013;14:68.

Harada H, Hayashi T, Nishi H, Kusaba K, Koga Y, Koga Y, et al. Phenotypic expression of a novel desmin gene mutation: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy followed by systemic myopathy. J Hum Genet. 2018;63:249–54.

Ariza A, Coll J, Fernandez-Figueras MT, Lopez MD, Mate JL, Garcia O, et al. Desmin myopathy: a multisystem disorder involving skeletal, cardiac, and smooth muscle. Hum Pathol. 1995;26:1032–7.

Munoz-Marmol AM, Strasser G, Isamat M, Coulombe PA, Yang Y, Roca X, et al. A dysfunctional desmin mutation in a patient with severe generalized myopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11312–7.

Henderson M, De Waele L, Hudson J, Eagle M, Sewry C, Marsh J, et al. Recessive desmin-null muscular dystrophy with central nuclei and mitochondrial abnormalities. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;125:917–9.

Menezes MP, Waddell L, Lenk GM, Kaur S, MacArthur DG, Meisler MH, et al. Whole exome sequencing identifies three recessive FIG4 mutations in an apparently dominant pedigree with Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease. Neuromuscul Disord. 2014;24:666–70.

Cummings BB, Marshall JL, Tukiainen T, Lek M, Donkervoort S, Foley AR, et al. Improving genetic diagnosis in Mendelian disease with transcriptome sequencing. Sci Trans Med. 2017;9:eaal5209.

Waddell LB, Monnier N, Cooper ST, North KN, Clarke NF. Using complementary DNA from MyoD-transduced fibroblasts to sequence large muscle genes. Muscle Nerve. 2011;44:280–2.

Cooper ST, Lo HP, North KN. Single section Western blot: improving the molecular diagnosis of the muscular dystrophies. Neurology. 2003;61:93–7.

Waddell LB, Tran J, Zheng XF, Bonnemann CG, Hu Y, Evesson FJ, et al. A study of FHL1, BAG3, MATR3, PTRF and TCAP in Australian muscular dystrophy patients. Neuromuscul Disord. 2011;21:776–81.

Fichna JP, Karolczak J, Potulska-Chromik A, Miszta P, Berdynski M, Sikorska A, et al. Two desmin gene mutations associated with myofibrillar myopathies in Polish families. PloS oNE. 2014;9:e115470.

Pinol-Ripoll G, Shatunov A, Cabello A, Larrode P, de la Puerta I, Pelegrin J, et al. Severe infantile-onset cardiomyopathy associated with a homozygous deletion in desmin. Neuromuscul Disord. 2009;19:418–22.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NHMRC Project Grant APP1080587 (DGM and STC; NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship APP1136197 (STC); University of Sydney Senior Fellowship (STC); Broad Centre for Mendelian Genomics Grant UM1 HG008900 (DGM).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LGR: WGS data analysis, Sanger sequencing segregation analysis, RT-PCR, contributed to manuscript preparation, editing of figures. LBW: preparation of figures, manuscript preparations, information collation from co-authors, immunohistochemistry experiment, analysis and figure. RG: PhD cohort—initial MPS analysis, clinical review, clinical summary. FJE: Western blot experiment, analysis and figure. BBC: RNAseq/IGV analysis. SB: RNAseq/IGV analysis, editing of figures. HJ: Informatics extraction and analysis of DES variants submitted to ClinVar and HGMD. M-XW: muscle histology analysis and contributed images to figure. SB: EM analysis and contributed images to figure. LK: cardiologist, clinical review, contributed images to figure. AC: Clinical review and management. DGMA: Broad collaboration, WES, WGS, RNAseq. STC: Oversight of analysis and experimentation. Supervision of research personnel. Analysed clinical, pathological and laboratory results. Wrote manuscript. Editing of figures.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

SC is director of Frontier Genomics Pty Ltd (Australia). Frontier Genomics has not traded (as of 12 November 2018). Frontier Genomics Pty Ltd (Australia) will not benefit from publication of these data. The remaining authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Riley, L.G., Waddell, L.B., Ghaoui, R. et al. Recessive DES cardio/myopathy without myofibrillar aggregates: intronic splice variant silences one allele leaving only missense L190P-desmin. Eur J Hum Genet 27, 1267–1273 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0393-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-019-0393-6

This article is cited by

-

Pathogenic deep intronic MTM1 variant activates a pseudo-exon encoding a nonsense codon resulting in severe X-linked myotubular myopathy

European Journal of Human Genetics (2021)

-

AAV-mediated cardiac gene transfer of wild-type desmin in mouse models for recessive desminopathies

Gene Therapy (2020)