Abstract

Clostridium difficile is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality particularly in hospital settings. In addition, treatment is very challenging due to the scarcity of effective therapeutic options. Thus, there remains an unmet need to identify new therapeutic agents capable of treating C. difficile infections. In the current study, we screened two FDA-approved drug libraries against C. difficile. Out of almost 3200 drugs screened, 50 drugs were capable of inhibiting the growth of C. difficile. Remarkably, some of the potent inhibitors have never been reported before and showed activity in a clinically achievable range. Structure–activity relationship analysis of the active hits clustered the potent inhibitors into four chemical groups; nitroimidazoles (MIC50 = 0.06–2.7 μM), salicylanilides (MIC50 = 0.2–0.6 μM), imidazole antifungals (MIC50 = 4.8–11.6 μM), and miscellaneous group (MIC50 = 0.4–22.2 μM). The most potent drugs from the initial screening were further evaluated against additional clinically relevant strains of C. difficile. Moreover, we tested the activity of potent inhibitors against representative strains of human normal gut microbiota to investigate the selectivity of the inhibitors towards C. difficile. Overall, this study provides a platform that could be used for further development of potent and selective anticlostridial antibiotics.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Lessa FC, Mu Y, Bamberg WM, Beldavs ZG, Dumyati GK, Dunn JR, et al. Burden of Clostridium difficile infection in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:825–34.

ECDC. European surveillance of Clostridium difficile infections. Surveillance protocol version 2.2. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. European Surveillance of Clostridium difficile infections. Surveillance protocol version 2.2. Stockholm: ECDC; 2015.

Khanna S, Pardi DS, Aronson SL, Kammer PP, Orenstein R, St Sauver JL, et al. The epidemiology of community-acquired Clostridium difficile infection: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:89–95.

Barra-Carrasco J, Paredes-Sabja D. Clostridium difficile spores: a major threat to the hospital environment. Future Microbiol. 2014;9:475–86.

Kelly CP, LaMont JT. Clostridium difficile–more difficult than ever. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1932–40.

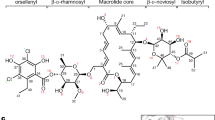

Cruz MP. Fidaxomicin (Dificid), a novel oral macrocyclic antibacterial agent for the treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea in adults. P T. 2012;37:278–81.

Mohammad H, AbdelKhalek A, Abutaleb NS, Seleem MN. Repurposing niclosamide for intestinal decolonization of vancomycin-resistant enterococci. Int J Antimicrobial Agents. 2018;51:897–904.

AbdelKhalek A, Abutaleb NS, Mohammad H, Seleem MN. Repurposing ebselen for decolonization of vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE). PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0199710.

Younis W, AbdelKhalek A, Mayhoub AS, Seleem MN. In vitro screening of an FDA-approved library against ESKAPE pathogens. Curr Pharm Des. 2017;23:2147–57.

Thangamani S, Eldesouky HE, Mohammad H, Pascuzzi PE, Avramova L, Hazbun TR, et al. Ebselen exerts antifungal activity by regulating glutathione (GSH) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in fungal cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1861:3002–10.

Younis W, Thangamani S, Seleem MN. Repurposing non-antimicrobial drugs and clinical molecules to treat bacterial infections. Curr Pharm Des. 2015;21:4106–11.

Thangamani S, Younis W, Seleem MN. Repurposing celecoxib as a topical antimicrobial agent. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:750.

Thangamani S, Younis W, Seleem MN. Repurposing ebselen for treatment of multidrug-resistant staphylococcal infections. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11596.

Thangamani S, Mohammad H, Younis W, Seleem MN. Drug repurposing for the treatment of staphylococcal infections. Curr Pharm Des. 2015;21:2089–100.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Methods for antimicrobial susceptibility testing of anaerobic bacteria, 8th ed. CLSI document M11-A8. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: 2012.

Shao X, AbdelKhalek A, Abutaleb NS, Velagapudi UK, Yoganathan S, Seleem MN, et al. Chemical space exploration around thieno[3,2-d]pyrimidin-4(3H)-one Scaffold led to a novel class of highly active clostridium difficile inhibitors. J Med Chem. 2019;62:9772–91.

McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, Bakken JS, Carroll KC, Coffin SE, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: 2017 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:e1–48.

Kumar M, Adhikari S, Hurdle JG. Action of nitroheterocyclic drugs against Clostridium difficile. Int J Antimicrobial Agents. 2014;44:314–9.

Jarrad AM, Karoli T, Blaskovich MA, Lyras D, Cooper MA. Clostridium difficile drug pipeline: challenges in discovery and development of new agents. J Med Chem. 2015;58:5164–85.

Surawicz CM, Brandt LJ, Binion DG, Ananthakrishnan AN, Curry SR, Gilligan PH, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:478–98.

Bolton RP, Culshaw MA. Faecal metronidazole concentrations during oral and intravenous therapy for antibiotic associated colitis due to Clostridium difficile. Gut. 1986;27:1169–72.

Ang CW, Jarrad AM, Cooper MA, Blaskovich MAT. Nitroimidazoles: molecular fireworks that combat a broad spectrum of infectious diseases. J Med Chem. 2017;60:7636–57.

Upcroft JA, Dunn LA, Wright JM, Benakli K, Upcroft P, Vanelle P. 5-Nitroimidazole drugs effective against metronidazole-resistant Trichomonas vaginalis and Giardia duodenalis. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 2006;50:344–7.

Jokipii L, Jokipii AM. Comparative evaluation of the 2-methyl-5-nitroimidazole compounds dimetridazole, metronidazole, secnidazole, ornidazole, tinidazole, carnidazole, and panidazole against Bacteroides fragilis and other bacteria of the Bacteroides fragilis group. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 1985;28:561–4.

Jokipii AM, Jokipii L. Comparative activity of metronidazole and tinidazole against Clostridium difficile and Peptostreptococcus anaerobius. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 1987;31:183–6.

Hedge DD, Strain JD, Heins JR, Farver DK. New advances in the treatment of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI). Therapeutics Clin Risk Manag. 2008;4:949–64.

Erkkola R, Jarvinen H. Single dose of ornidazole in the treatment of bacterial vaginosis. Annales Chirurgiae et Gynaecologiae Supplementum. 1987;202:94–6.

Gorenek L, Dizer U, Besirbellioglu B, Eyigun CP, Hacibektasoglu A, Van Thiel DH. The diagnosis and treatment of Clostridium difficile in antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Hepato-Gastroenterol. 1999;46:343–8.

Gookin JL, Copple CN, Papich MG, Poore MF, Stauffer SH, Birkenheuer AJ, et al. Efficacy of ronidazole for treatment of feline Tritrichomonas foetus infection. J Vet Intern Med. 2006;20:536–43.

Steiner JM, Schwamberger S, Pantchev N, Balzer HJ, Vrhovec MG, Lesina M, et al. Use of ronidazole and limited culling to eliminate tritrichomonas muris from laboratory mice. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2016;55:480–3.

Gooyit M, Janda KD. Reprofiled anthelmintics abate hypervirulent stationary-phase Clostridium difficile. Sci Rep. 2016;6:33642.

Rajamuthiah R, Fuchs BB, Conery AL, Kim W, Jayamani E, Kwon B, et al. Repurposing salicylanilide anthelmintic drugs to combat drug resistant Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0124595.

Tharmalingam N, Port J, Castillo D, Mylonakis E. Repurposing the anthelmintic drug niclosamide to combat Helicobacter pylori. Sci Rep. 2018;8:3701.

AbdelKhalek A, Abutaleb NS, Mohammad H, Seleem MN. Antibacterial and antivirulence activities of auranofin against Clostridium difficile. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2019;53:54–62.

Ghannoum MA, Rice LB. Antifungal agents: mode of action, mechanisms of resistance, and correlation of these mechanisms with bacterial resistance. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1999;12:501–17.

Heerding DA, Chan G, DeWolf WE, Fosberry AP, Janson CA, Jaworski DD, et al. 1,4-Disubstituted imidazoles are potential antibacterial agents functioning as inhibitors of enoyl acyl carrier protein reductase (FabI). Bioorg medicinal Chem Lett. 2001;11:2061–5.

Marreddy RKR, Wu X, Sapkota M, Prior AM, Jones JA, Sun D, et al. The fatty acid synthesis protein enoyl-ACP reductase II (FabK) is a target for narrow-spectrum antibacterials for Clostridium difficile Infection. ACS Infect Dis. 2019;5:208–17.

Rani N, Sharma A, Singh R. Imidazoles as promising scaffolds for antibacterial activity: a review. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2013;13:1812–35.

McVay CS, Rolfe RD. In vitro and in vivo activities of nitazoxanide against Clostridium difficile. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 2000;44:2254–8.

Musher DM, Logan N, Bressler AM, Johnson DP, Rossignol JF. Nitazoxanide versus vancomycin in Clostridium difficile infection: a randomized, double-blind study. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:e41–6.

Hoffman PS, Sisson G, Croxen MA, Welch K, Harman WD, Cremades N, et al. Antiparasitic drug nitazoxanide inhibits the pyruvate oxidoreductases of Helicobacter pylori, selected anaerobic bacteria and parasites, and Campylobacter jejuni. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 2007;51:868–76.

Willcox RR. Treatment of vaginal trichomoniasis with 2-acetylamino-5-nitrothiazole (aminitrozole) given orally. Br J Vener Dis. 1957;33:115–7.

Kalinichenko NF. Nitazole–an antimicrobial substance. Mikrobiol Z. 1998;60:83–91.

Villegas F, Angles R, Barrientos R, Barrios G, Valero MA, Hamed K, et al. Administration of triclabendazole is safe and effective in controlling fascioliasis in an endemic community of the Bolivian Altiplano. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1720.

Andrews P, Bonse G. Chemistry of anticestodal agents. In: Campbell WC, Rew RS, editors. Chemotherapy of Parasitic Diseases. Boston, MA: Springer; 1986.

Perez-Cobas AE, Moya A, Gosalbes MJ, Latorre A. Colonization resistance of the gut microbiota against Clostridium difficile. Antibiotics. 2015;4:337–57.

Wust J. Susceptibility of anaerobic bacteria to metronidazole, ornidazole, and tinidazole and routine susceptibility testing by standardized methods. Antimicrobial Agents Chemother. 1977;11:631–7.

Nenoff P, Koch D, Kruger C, Drechsel C, Mayser P. New insights on the antibacterial efficacy of miconazole in vitro. Mycoses. 2017;60:552–7.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01AI130186.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

AbdelKhalek, A., Mohammad, H., Mayhoub, A.S. et al. Screening for potent and selective anticlostridial leads among FDA-approved drugs. J Antibiot 73, 392–409 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41429-020-0288-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41429-020-0288-3

This article is cited by

-

Drug repurposing strategy II: from approved drugs to agri-fungicide leads

The Journal of Antibiotics (2023)

-

In vivo efficacy of auranofin in a hamster model of Clostridioides difficile infection

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

High-throughput screening identifies a novel natural product-inspired scaffold capable of inhibiting Clostridioides difficile in vitro

Scientific Reports (2021)