Abstract

Adoptive cell therapy of solid tumors with reprogrammed T cells can be considered the “next generation” of cancer hallmarks. CAR-T cells fail to be as effective as in liquid tumors for the inability to reach and survive in the microenvironment surrounding the neoplastic foci. The intricate net of cross-interactions occurring between tumor components, stromal and immune cells leads to an ineffective anergic status favoring the evasion from the host’s defenses. Our goal is hereby to trace the road imposed by solid tumors to CAR-T cells, highlighting pitfalls and strategies to be developed and refined to possibly overcome these hurdles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Facts

-

Unparalleled clinical efficacy has been demonstrated using anti CD19-CAR-T cells to treat refractory B-cell malignancies.

-

Many are the challenges imposed by solid tumors for a successful development of CAR T-cell immunotherapy.

-

Genetically modified T cells can be alternatively generated using transposons systems (e.g., Sleeping Beauty) to stably introduce CARs in T lymphocytes.

Open questions

-

How CARs should be designed and engineered to be effective in the treatment of solid tumors?

-

Which strategies need to be developed and refined to improve the balance between favorable and unfavorable effects for better therapeutic benefits?

-

What are the priorities for CAR-T cell therapy that must be addressed as they concern safety and efficacy?

-

Can the use of genome editing techniques be helpful in generating CAR-armed T lymphocytes suitable for the treatment of solid tumors?

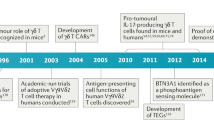

Introduction

T cells normally build poor or no response against syngeneic transformed cells, (a) for their poor antigenicity, (b) because transformed cells are not phenotypically foreign, and (c) for the generalized immunosuppressive conditions often associated with cancer. For these reasons, adequate immune responses against tumors have seldom been observed, at least in patients treated with chemotherapeutic agents1,2. These observations stimulated oncologist and immunologists to boost and activate the T-cell responses against tumor cells, attempts that over the years, never accomplished straightforward clinical results.

Recent knowledge shows that the immune system is kept in shape through a delicate network of signaling pathways delivered by T-cell activating receptors (accelerators) and inhibitory receptors (brakes) to regulate the balance between immune response and immune tolerance3,4,5. This established the platform for developing the “alternative strategy” aimed to take the brakes off the anti-tumor immune responses. The successful use of immune-checkpoint inhibitors in clinical trials highlights the enormous potentials of the immune system to efficiently react against virtually any kind of tumor cell. The advantages in terms of significant antitumor activity, induction of long-lasting responses, and favorable safety profile obtained with the use of checkpoint inhibitors (anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies and anti-CTLA-4), definitely proved the concept that the immune cellular responses may be pivotal to regulate anti-cancer activities6,7.

Together with the check inhibition, the adoptive cell therapy (ACT) with chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) redirected T cells is perhaps the most attractive anti-cancer strategy.

CARs encode for transmembrane chimeric molecules with dual function: (a) immune recognition of tumor antigens expressed on the surface of tumor cells; (b) active promotion and propagation of signaling events controlling the activation of the lytic machinery. This system has several advantages: (1) to provide “reprogrammed T-cells” of an ex-novo activation mechanism; (2) to brake the tolerance acquired by tumor cells, and (3) bypass restrictions of the HLA-mediated antigen recognition, over-stepping one of the barriers to a more widespread application of cellular immunotherapy8.

Eshhar and coworkers were the first to demonstrate that linking the scFv with the TCR ζ-chain or γ-chain for signal transduction, provides T lymphocytes with Ab-type specificity and activates all the functions of an effector cell, including the production of IL-2 and the lysis of target cells9. Since then, efforts have been dedicated to produce a number of CARs designed to implement quality, strength and duration of signals delivered by the chimeric molecules. Variability in the functional properties has been obtained by engineering CARs expressing the ζ-chain alone (1st generation) or in tandem with the CD28 (2nd generation), or variably combined with a third signaling domain (3rd generation), such as the 4-1BB (CD137), the OX40 (CD134), ICOS and CD27, with the idea to enhances T-cell proliferation, IL-2 secretion, survival and cytolytic activity. The 4th generation includes “Armored CARs”, designed to increase persistence of engineered T cells in tumor’s microenvironment. Armored CARs combine the CAR functional activities with the secretion of IL-2 or IL-12 expressed as an independent gene in the same CAR vector10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 (Fig.1).

CARs comprise an extracellular domain with a tumor-binding moiety, typically a single-chain variable fragment (scFv), followed by a hinge/spacer of varying length and flexibility, a transmembrane (TM) region, and one or more signaling domains associated with the T-cell signaling. The 1st CARs generation is equipped with the stimulatory domain of the ζ-chain; in the 2nd CARs generation the presence of costimulatory domains (CD28) provides additional signals to ensure full activation; in the 3rd generation an additional transducer domain (CD27, 41-BB or OX40) is added to the ζ-chain and CD28 to maximize strength, potency, and duration of the delivered signals; the 4th generation includes armored CARs, engineered to synthetize and deliver interleukins (green ovals)

Although the initial attempts to treat patients affected by a variety of solid and liquid tumors, the breakthrough with CAR-T cells therapy was achieved targeting B-cell hematologic tumors.

The use of anti-CD19 CAR T cells have demonstrated consistently high antitumor efficacy in children and adults affected by relapsed B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma, with percentage of complete remissions ranging from 70 to 94% in the different trials19.

Based on these results, the FDA has approved two immunotherapies with anti-CD19 modified T cells, KYMRIAH [tisagenlecleucel (August 2017)] and YESCARTA [axicabtagene ciloleucel (October 2017)]. These are now a second line treatment for patients up to 25 years of age with B-ALL (KYMRIAH) and for adults with certain types of large B-cell lymphoma (YESCARTA). Similar for the presence of an anti-CD19 murine scFv, they signal through a different costimulatory domain fused in tandem with the CD3 ζ-chain: 4-1BB for KYMRIAH, and CD28 for YESCARTA.

Other B-cell antigens have been targeted in preclinical models, including CD20, CD22, CD23, ROR1, and the kappa light chain. In principle, the treatment of B-cell malignancies with CAR-T cells leads to almost entire B cells repertoire depletion. In this case, the problems derived by the disappearance of B cells from blood can be partially mitigated by immunoglobulins administration. However, depletion of other cell lineages might not be as manageable, and the use of CAR-T cell therapies might be restricted only to specific hematopoietic lineages. In addition, large tumor masses clearance observed in these trials was accompanied by acute and often severe syndrome requiring intensive care, following massive release of cytokines from on-target activated T cells20,21,22.

CAR-T cells therapy for solid tumors

Less exciting conclusions can be derived from clinical trials designed for the treatment of solid tumors with engrafted CAR-T lymphocytes. Although from most of the trials we do not have yet evaluable data, there is enough proof to establish a solid platform for development of CAR-T cells therapy for solid cancers. A good clinical outcome depends on several parameters: (1) choice of the target epitope; (2) CAR architecture; (3) CAR-T cell doses, frequencies and way of administration of CAR-T cells; (4) efficient tumor homing and long-term survival in the tumor environment; (5) patients’ lymphodepletion prior to the administration of CAR-T cells, and subsequent cytokine support.

A key factor responsible for the poor specificity and poor efficacy of CAR-T against malignant epithelial cells is the lack of specific targetable antigens. An ideal target is the signaling active splice variant of EGFR (EGFRvIII), because specifically expressed on glioma cells and indispensable for cell survival23. However, encouraging results from early phase trials have been only obtained in neuroblastoma patients treated with anti-GD2 CAR-T cells, and in ErbB2-positive sarcomas treatment24. Focus is now on antigens preferentially expressed in certain types of cancers (Table 1).

Few other factors, besides the differences in the chosen targets, might be responsible for failure of CAR-T cell therapies in solid tumors. The ACT in melanoma requires more cells, more profound lymphodepletion and the use of IL-2 support to obtain optimal results25,26,27. Furthermore, to exploit their cytotoxic function CAR-T lymphocytes need to overcome the limitations imposed by the physical and functional barriers preserving epithelial and mesenchymal compartments. Thus, in perspective, T cells extravasation, tumor homing and persistence in a hostile microenvironment are goals to be accomplished to increase the chances of treating solid tumors with CAR-T cell immunotherapy.

Extravasation

How to attract CAR-T lymphocytes to solid tumors neoplastic lesions? In principle, activated T cells acquire the expression of a cohort of homing molecules, including E- and P-selectin ligands that mediate T cells rolling on the endothelium, and subsequent chemokines receptors engagement such as CXCR3, CXCL9, and CXCL10. The interaction between chemokines receptors and their ligands facilitates the expression of the LFA-1 and VLA-4 integrins, allowing cell adhesion through to ICAM-1 and VCAM-1, respectively. These features have inspired the engineering of CARs able to target components of the EC matrix, such as αvβ6 integrin28 and VEGF receptor-2, usually overexpressed on tumor vessels cells29. The idea to target the tumor vascular environment responds to the ability of neoplastic cells to drive angiogenic responses in their favor. EC matrix-directed CAR-T cells would possibly be able to destroy the architecture of the neo-vessels and likely limit the need for T cells to penetrate tumors.

Inefficient traffic

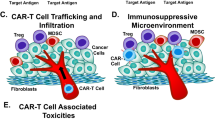

Trafficking of immune cells toward tumor foci is a dynamic process controlled by a complex network of interactions at multiple levels. The unbalanced secretion of cytokines from tumor cells is one of the major issues responsible for insufficient homing of CD8+ CXCR3high T cells at the tumor side. Phenotypically mature T cells express adhesion molecules and chemokines receptors necessary for the interactions with endothelial cells. In particular, the G protein-coupled receptors CXCR3 and CCR5 are often expressed in active tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) from melanoma, breast and colorectal cancers, indicating their importance in regulating T-cell trafficking30. On the other hand, lack of expression of the cognate ligands, CXCL9 and CXCL10 in many tumor cell types hinders the recruitment of CD8+ effector and memory T lymphocytes through chemokines receptors. The tumor endothelium also constitutes a real barrier against T-cell infiltration by overexpressing receptors and ligands. During extravasation, T lymphocytes actively degrade the main components of the sub-endothelial membrane basement and the extracellular matrix, including heparan sulphate proteoglycans (HSPGs)31. Therefore, CAR-T cells attacking solid tumors must be able to degrade HSPGs by releasing heparanase (HPSE) to access tumor cells. Recent studies have shown that HPSE deficiency in in vitro-engineered and cultured tumor-specific T cells may limit their antitumor activity in stroma-rich solid tumors32.

Tumor microenvironment

To make matters worse, the tumor microenvironment is inhospitable and inaccessible to the invasion of immune cells, because of hypoxia, low nutrients, and for the metabolic acids high concentration that make T cells unable to proliferate and produce cytokines. The absence of important amino acids such as tryptophan, lysine, and arginine, is responsible for the autophagic processes and stress responses activation, inducing T cells to exploit the resources of intracellular nutrients. Immunosuppressive roles have been ascribed to numerous substances produced by tumor and immune cells. Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and adenosine are released in large quantities by cancer cells and macrophages in hypoxic conditions, and inhibit T lymphocytes proliferation by activating G protein-coupled receptors and protein kinase A. Moreover, tumor infiltrate is enriched in Tregs, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC), TAM and TAN (tumor-associated macrophages and tumor-associated neutrophils) favoring tumor survival by the secretion of TGF-β, IL-10, nitric acid, and indoleamine dioxygenase 2–3. CD4+/FOXP3+ Tregs are suppressor T lymphocytes able to down-modulate immune effector cells activities through multiple mechanisms, including cell–cell contact inhibition and release of soluble factors such as TGF-β and IL-1033. To counteract these immunomodulatory activities, CAR-T lymphocytes resistant to TGF-β suppression have been generated by the expression of a dominant negative TGF-β receptor, demonstrating their superior antitumor activity in animal models34.

Tumor cells, TILs and immature myeloid cells, are responsible for a large part of ROS production35, which can downmodulate CD3-ζ receptor levels, making TCR-mediated T-cell activation less efficient36,37. The peculiar aspects of the tumor milieu rich of inflammatory activity provided the rational for constructing CAR-T cells expressing catalase to reduce H2O2 and counteract the ROS-induced unresponsiveness of these and bystander cells38.

IL-4 is another immunosuppressive cytokine that synergizes with IL-10 and TGF-β and promotes activation of macrophages into M2 cells. IL-4’s suppressive effect can be converted into stimulatory effects by chimeric receptors that, engineered to express the IL-4 receptor ectodomain, generate active signals mimicking the IL-2 or IL-7 receptors39,40. CAR-T cells expressing “switch” CARs have shown improved capacity to kill TAA-expressing tumor cells41,42.

Positive inputs come from experimental use of “Armored CAR” in solid tumor cell therapy. TRUCKS (T cell Redirected Universal Cytokine killing) are engineered to release IL-12 with the intent to mitigate the tumor microenvironment hostile activity. Notably, IL-12 enhances recruitment and functions of innate immunity cells, with the consequence of antigen negative cancer cells increased destruction42,43.

Despite Armored CARs have demonstrated superior anti-tumor activity in xenograft models compared to conventional CAR-T, the abundant production of cytokines often results in a severe cytokine release syndrome (CRS) without particular increased efficacy in clinical trials18.

“Safety” and “efficacy”: the two checkpoints of CAR-T cell therapy

The critical point of ACT with chimeric receptors is the need to control unwanted immunological CAR-T cells responses. CAR-T cell therapy’s efficacy is largely counteracted by the occurrence of toxicity, sign at the same time of good performing T-cell activity. For this reason, “safety” and “efficacy” are hallmarks for the improvement of CAR-T cell therapy, and their harmonization will require combination with other therapeutic approaches, to effectively treat solid tumors44.

CRS is occurring in almost 80% of the patients treated with anti-CD19 CAR-T cells and can be fatal or life threatening20,45. Symptoms include transient neurologic toxicity, febrile neutropenia, cytopenia not resolved by day 28, and infections. This is mostly due to massive release of tumor cell components in the blood for rapid destruction of a large tumor mass (“on-target/on-tumor” toxicity), and to pro-inflammatory cytokines released by CAR-T cells, vascular endothelial cells, and others, resulting in monocyte and macrophage activation with the risk of multiple organ failure.

While CRS can be devastating in course of treatment of liquid tumors, the risk for “on-target/on-tumor” toxicity for solid tumor seems to be lower. This can be at least partially explained by the different stoichiometry in effector-target cell composition reachable in liquid rather than solid tumors, ensuring target killing in a relatively short time. Secondly, the magnitude of CRS correlates with the tumor burden20,46.

The other form of toxicity is the on-target/off-tumor toxicity. This is related to the difficulty to identify tumor-specific cell-surface molecules targetable by CAR-T cells without serious side effects. Most antigens are not tumor selective and, particularly in solid tumors, tend to be merely overexpressed. Furthermore, cancer cells redefine over time density and stoichiometry of antigen receptors, with significant implication in predicting the safety profile. For these reasons, the risk of an on-target/off-tumor toxicity is higher in solid tumors and, at least in one case, severity of this reaction may have caused patient death47.

In principle, toxicity can be controlled at several levels. One way is to administer required numbers of cells through two (30 + 70)% or three doses (10 + 30 + 60)%, possibly using RNA transiently-engineered CAR-T cells in the first administration to minimize the on-target off-tumor activity48,49,50. Another way is to start the treatment at the earlier stages of tumor development, before the number of cancer cells becomes too high.

The need to minimize on- and off-tumor’s reactivity, is the major criterion orienting the conceptual design of dual CAR-T antigen recognition. At least two types of approaches are currently under investigation. In the first approach, target selectivity is ensured by a double recognition of two tumor antigens expressed by the same cell, while the second strategy implies the design of inhibitor chimeric antigen receptors called iCARs, able to divert CAR-T cells activity from normal tissues51,52 (Fig. 2).

Tandem CARs (TanCAR) mediate bispecific activation of T cells through the engagement of two chimeric receptors designed to deliver stimulatory or costimulatory signals in response to an independent engagement of two different tumor associated antigens (TAAs). iCARs use the dual antigen targeting to shout down the activation of an active CAR through the engagement of a second suppressive receptor equipped with inhibitory signaling domains

Tandem CAR

In the first case, the dual recognition of different epitopes by two CARs diversely designed to either deliver killing (i.e. through ζ-chain) or costimulatory signals (i.e., through CD28) allows a superior activation of the reprogrammed T cells. Consequently, this is a safer path restricting Tandem CAR’s activity to cancer cell expressing simultaneously two antigens rather than one. In this case, the potency of delivered signals in engineered T cells will remain below threshold of activation and thus ineffective in absence of the engagement of costimulatory receptor (CCR)53. More importantly, this strategy is potentially suitable to control the on-target/off-tumor toxicity, because the combinatorial antigen recognition enhances selective tumor eradication and protects normal tissues expressing only one antigen from unwanted reactions. In refined strategies for fine-tuning of signals, CARs can be designed to provide weaker strength of activation, while CCR can be equipped with modules for stronger costimulation. The mechanism of dual antigen recognition is also utilized by T lymphocytes in secondary lymphoid organs where T cells receive both activating and costimulatory signals necessary to bust their activity and to sustain their life span during recirculation54.

Inhibitory CAR

Inhibitory CARs (iCARs) are designed to regulate CAR-T cells activity through inhibitory receptors signaling modules activation, typically utilized by T lymphocytes to mitigate the immune responses. This approach combines the activity of two chimeric receptors, one of which generates dominant negative signals limiting the responses of CAR-T cells activated by the activating receptor. iCARs can switch off the response of the counteracting activator CAR when bound to a specific antigen expressed only by normal tissues. In this way, iCARs-T cells can distinguish cancer cells from healthy ones, and reversibly block functionalities of transduced T cells in an antigen-selective fashion (Fig. 2).

In human T lymphocytes, PD-1 and CTLA-4 are inhibitor receptors that reversibly control reduction of TCR signaling potency and can be utilized to mitigate the activation of chimeric receptors. CTLA-4 or PD-1 intracellular domains in iCARs trigger inhibitory signals on T lymphocytes, leading to less cytokine production, less efficient target cell lysis, and altered lymphocyte motility55. Critical for the efficacy of iCAR-T cell therapy is antigens selection, because the anti-tumor activity would depend on tissue distribution and stoichiometry between normal and tumor antigens on target cells.

Gene delivery

An important aspect is the vector’s choice for transferring genes in T lymphocytes. The ideal carrier must meet criteria of efficacy, delivery, and safety. The most used carriers are retroviral (RV) and lentiviral (LV)56,57,58. Both RV and LV systems account for excellent gene transduction efficiency, but differ for the ability to infect resting rather than dividing cells, and for the integration mechanisms that favor privileged areas of the genome rather than others56,57,58,59,60.

The ability of LV-based vectors to integrate transgenes in non-replicating cells reduces time of ex vivo cell manipulation, with the advantage of obtaining T lymphocytes with a “young” and poorly differentiated phenotype, optimal for therapeutic purposes61.

However, the preparation of viral particles for gene therapy remains tedious and carries the risks of contamination by infectious agents, including the replication-competent virus generated by the recombination between vector and packaging cell lines.

The major clinical problems related to the usage of RVs and LVs are the development of innate immune and inflammatory responses to viral vectors62,63, and the risk linked to preferential integration near promoters or transcriptional units, with increased chances of causing adverse effects57,58,59,60.

Alternative to viral systems are the transposons PiggyBac (PB) and Sleeping Beauty (SB), allowing integration of large DNA sequences between two ITRs in the host genome by a “cut and paste” transposase’s mechanism64 (Fig. 3). The use of transposons in gene therapy would be advantageous for several reasons: simplicity of gene transduction (can be introduced into T cells by nucleofection), safety for both patients and operators, less complexity, minor cost, and less GMP requirements. PB and SB allow excellent standard of gene expression and integration in absence of foreign proteins that can elicit adverse reactions (Fig. 4). Furthermore, since the transposition mechanisms do not involve reverse transcription, transposon vectors are not prone to incorporating mutations and eliminate the risk of rearrangements of the expression cassette that integrates into chromosomal DNA in an intact form65,66.

Transposition is possible through a dual vector system that comprises the transposon containing the transgene flanked by two inverted terminal repeats, and a transposase that mobilizes the transposon. The CAR is integrated into the genome through a cut-and-paste mechanism SB transposon vectors are characterized by the presence of specular IR/DR sequences, target for the transposase. The SB vector contains the gene of interest (CAR). The SB transposase (SB-100×) binds to the IR/DR sequences and cuts the vector to release the transposable portion of DNA. TA sequences in the host DNA act as acceptors of the transposed element. The PB transposon is a mobile genetic element that transposes the gene of interest (CAR) from the vector to the host DNA. The l’hyperactive PiggyBac (Hy7 PB) transposase recognizes the transposon-specific “inverted terminal repeats” sequences (ITRs) located at the ends of the gene of interest. Transposition occurs between two TTAA acceptor sites located in the host DNA

Substantial improvement of these techniques has been demonstrated with the introduction of SB-transposition from minimalistic DNA vectors called Minicircles (MCs). MCs offer more stability, superior gene expression, and less toxicity to T cells compared to SB plasmids67,68. The integration profile of a CD19-CAR mobilized through MCs resulted to be highly favorable displaying a near-random integration pattern, in contrast to LVs that prefer for transcriptionally active genes69. Several clinical trials in phase I and II are ongoing with SB-generated CD19 CAR-T cells70, and one with MUC1-CAR for metastatic breast cancer is currently under review (US-1360).

The problem of target loss and antigen escape

An emerging threat to CAR-T immunotherapy is the antigen escape that makes CAR-T cells inefficient against cancer cells. CAR-T cells tumor sculpting exerts a selective pressure involving the selection of antigen-negative cells over time. This phenomenon has been described in many clinical studies, including glioblastoma trial with anti-ErbB2-CAR71. Appearance of Ag-negative cells limits per se the efficacy of immune therapy, highlighting the importance of developing approaches that quickly allow targeting other antigens at the appearance of the new neoplastic phenotype.

Flexibility to the limitation of having one CARs for one antigen has been illustrated in the seminal work of Tamada et al. describing a 3rd generation CAR equipped with an scFv able to bind FITC-labeled monoclonal antibodies directed against tumor antigens72. In this case, the anti-FITC CAR-T lymphocytes were able of efficient target lysis, T-cell proliferation, and cytokine production.

This strategy has been refined by Clemenceau and colleagues by engineering an FcγRIIIa-158(V/V)-FcεRIγ chimeric receptor able to bind any mAb directed against any cancer cell surface antigen73. The idea is to combine the therapeutic activity of monoclonal antibodies utilized in cancer therapy with the recruitment of cellular components of the immune system (Fig. 5). The proof of concept has been validated in other laboratories by Kudo K., Ochi F., and D’Aloia MM., engineering CD16-CRs able to complex IgGs with an extracellular FcγRIII binding domain and to deliver biochemical signals through either 4-1BB/ζ-chain or 28-ζ-chain74,75,76. Their FcγRIIIa CRs were able to trigger antibody-dependent cytotoxicity (ADCC)-like activity in transduced T lymphocytes against opsonized CD20+ lymphoma cells, in vitro or when injected in NOD-scid-IL2rgnull mice in presence of rituximab.

Further advantage of this strategy is the possibility to control unwanted reactions by the administration of high doses of immunoglobulins that might compete with the FcγR for binding. Moreover, the clearance of the antibodies from blood in about three weeks would offer a further level of control for CD16-CR-T cells activity, protecting patients from GVH reactions. On the other hand, the use of CD16-CR-T cells might be limited by the competition of therapeutic mAbs with serum immunoglobulins for binding to the FcγR-CRs, thus hampering their ability to mediate ADCC. Further restrictions to their usage can be hypothesized for patients affected by autoimmune diseases or diseases mediated by cross-reacting antibodies. In both cases, the high levels of self-reacting Abs might redirect engineered T cells against self-antigens.

Genome editing

The rapid advancement of genome-editing techniques holds much promise in the field of human gene therapy. By delivering the Cas9 protein and appropriate guide RNAs into cells, the genome can be cut at any desired location, disrupting or changing the sequence of specific genes with the intent to generate armed lymphocytes with increased capabilities of extravasation and survival in tumor microenvironment, or with less potential of toxicity.

Currently, three classes of gene-editing proteins are available: Zinc-Finger, TALENs (Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases), and CRISPR/Cas9 (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Palindromic Repeats/CRISPR-associated-9)77,78. Each of them can guide the insertion of the gene of interest in desired sites through the binding of user-defined DNA or RNA sequences, inducing a double-stranded DNA break.

Genome editing has been used to disrupt the TCR complex by targeting either TRAC or TRBC to make T lymphocytes defective of endogenous TCR, less prone to induce off-tumor reactivity in the form of GVHD78,79. Also interesting are the knockout of PD-180 and CTLA-4 genes regulating the T-cell checkpoint inhibitors and the silencing of DGK in the TGF-β pathway, made to create the most resistant lymphocytes to immunosuppressive stimuli, including those from tumor microenvironment81.

Another possibility is to guide the insertion of transgenes in specific genome sites without affecting endogenous gene structure or expression. Extra-genic regions of the genome called “safe harbors” (GSH) could be able to accommodate the expression of newly integrated DNA without generating adverse effects on the host cell. Three intragenic sites have been proposed as safe harbors (AAVS1, CCR5, and ROSA26) although all of them are in fairly gene-rich regions and are near genes that have been implicated in cancer82.

Concluding remarks

Although majority of CAR T-cell clinical trials are conducted in the setting of hematological malignancies, solid-tumor oncology represents an urgent clinical need. Besides the difficulties of how to reprogram T cells to drive them to tumor sites and survive in the microenvironment, there are few other issues that become more compelling in the perspective of solid tumors CAR-T cells treatment.

One of the major questions would be: which is the best solid tumor to target? The target antigen specificity is a solid selection criterion. As mentioned, the rational for CAR-T cell therapy of glioblastoma is the peculiar expression of the highly specific EGFRvIII antigen in this tumor.

Cancer immunotherapy widely relies on the administration of mAbs directed against signaling receptors or tumor antigens. However, their efficacy and clinical success largely depends on the presence of immune effector cells with ADCC activity in the tumor infiltrate, including NK cells83,84,85,86,87. This raises few considerations. It is necessary to identify cancer types where the conspicuous presence of immune cells in the tumor microenvironment would indicate a relative permissive status for engrafted T cells to rich tumor foci and possibly be effective against cancer cells88,89,90. To this extent, several studies have demonstrated that the mutational load and the frequency of neoantigens correlates with the response to immunotherapy in melanoma, lung, and microsatellite instability (MSI)-positive colorectal cancers91,92. It is not singular mutations that predict patients’ clinical outcome, but the presence of a high number of mutations and global T-cell responses in the tumor microenvironment. The second is that strategies aimed to combine therapeutic activities of the mAbs used with the potential of a T cell-dependent activation at the tumor site might be ideal. FcγR-CRs can target more than one antigen, sequentially or in combination, thus limiting the risk of immune escape due to emergence or outgrowth of antigen-null tumor cells. However, no clinical trials have been conducted to date to test any of these hypotheses.

Another aspect defining CAR T-cell activity is the affinity for the antigen. High-affinity binding enables CAR driven T-cell effector responses against target cells expressing relatively low levels of antigen93. This impacts on a variety of adverse effects occurring immediately or weeks after CAR-T infusion, and there is need as well to invest more research in this field to improve control of off-target toxicity.

There is also the need to implement strategies to control life span of engineered T cells. CAR-T cells can persist and even expand over time, with the consequence of mediating their effects, both therapeutic and deleterious. The introduction of cellular switches to eliminate CAR-T cells in case of adverse events is therefore safe and recommended.

As a final consideration, CAR-T technologies should be validated in preclinical settings using immune competent animals. The immunocompromised mice models cannot recapitulate the immunomodulatory effects of the hosts endogenous immune system, including pathological responses such as CRS, or the immunosuppressive effects generated by the tumor microenvironment on adoptively transferred T cells.

We believe the effectiveness of these living drugs in treating late-stage liquid cancers raised the exciting possibility of a breakthrough approach in cancer therapy, but it needs to be shaped and refined to be impactful in the treatment of solid tumors.

References

Medler, T. R., Cotechini, T. & Coussens, L. M. Immune response to cancer therapy: mounting an effective antitumor response and mechanisms of resistance. Trends Cancer 1, 66–75 (2015).

Bracci, L., Schiavoni, G., Sistigu, A. & Belardelli, F. Immune-based mechanisms of cytotoxic chemotherapy: implications for the design of novel and rationale-based combined treatments against cancer. Cell. Death Differ. 21, 15–25 (2014).

Pardoll, D. M. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 252–264 (2012).

Buchbinder, E. I. & Desai, A. CTLA.-4 and PD-1 pathways. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 39, 98–106 (2016).

Hodi, F. S. et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 711–723 (2010).

Lipson, E. J. et al. Durable cancer regression off-treatment and effective reinduction therapy with an anti-PD-1 antibody. Clin. Cancer Res. 19, 462–468 (2013).

Cogdill, A. P., Andrews, M. C. & Wargo, J. A. Hallmarks of response to immune checkpoint blockade. Br. J. Cancer 117, 1–7 (2017).

Gross, G. & Eshhar, Z. Endowing T cells with antibody specificity using chimeric T cell receptors. FASEB J. 6, 3370–3378 (1992).

Eshhar, Z., Waks, T., Gross, G. & Schindler, D. G. Specific activation and targeting of cytotoxic lymphocytes through chimeric single chains consisting of antibody-binding domains and the gamma or zeta subunits of the immunoglobulin and T-cell receptors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 90, 720–724 (1993).

Koehler, H., Kofler, D., Hombach, A. & Abken, H. CD28 costimulation overcomes transforming growth factor-β-mediated repression of proliferation of redirected human CD4+and CD8+T cells in an antitumor cell attack. Cancer Res. 67, 2265–2273 (2007).

Long, A. H. et al. 4-1BB costimulation ameliorates T cell exhaustion induced by tonic signaling of chimeric antigen receptors. Nat. Med. 21, 581–590 (2015).

Wang, J. et al. Optimizing adoptive polyclonal T cell immunotherapy of lymphomas, using a chimeric T cell receptor possessing CD28 and CD137 costimulatory domains. Hum. Gene Ther. 18, 712–725 (2007).

Carpenito, C. et al. Control of large, established tumor xenografts with genetically retargeted human T cells containing CD28 and CD137 domains. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 3360–3365 (2009).

Milone, M. C. et al. Chimeric receptors containing CD137 signal transduction domains mediate enhanced survival of T cells and increased antileukemic efficacy in vivo. Mol. Ther. 17, 1453–1464 (2009).

Zhong, X.-S., Matsushita, M., Plotkin, J., Riviere, I. & Sadelain, M. Chimeric antigen receptors combining 4-1BB and CD28 signaling domains augment PI3kinase/AKT/Bcl-XL activation and CD8+T cell-mediated tumor eradication. Mol. Ther. 18, 413–420 (2010).

Töpfer, K. et al. DAP12-based activating chimeric antigen receptor for NK cell tumor immunotherapy. J. Immunol. 194, 3201–3212 (2015).

Karlsson, H. et al. Evaluation of intracellular signaling downstream chimeric antigen receptors. PLoS ONE 10, e0144787 (2015).

Pegram, H. J., Park, J. H. & Brentjens, R. J. CD28z CARs and armored CARs. Cancer J. 20, 127–133 (2014).

Wang, Z., Wu, Z., Liu, Y. & Han, W. New development in CAR-T cell therapy. J. Hematol. Oncol. 10, 53 (2017).

Davila, M. L. et al. Efficacy and toxicity management of 19-28z CAR T cell therapy in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med 6, 224ra25 (2014).

Maude, S. L. et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 371, 1507–1517 (2014).

Lee, D. W. et al. T cells expressing CD19 chimeric antigen receptors for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet 385, 517–528 (2015).

Sampson, J. H., Archer, G. E., Mitchell, D. A., Heimberger, A. B. & Bigner, D. D. Tumor-specific immunotherapy targeting the EGFRvIII mutation in patients with malignant glioma. Semin. Immunol. 20, 267–275 (2008).

Ahmed, N. et al. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-specific chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for the immunotherapy of HER2-positive sarcoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 1688–1696 (2015).

Goff, S. L. et al. Randomized, prospective evaluation comparing intensity of lymphodepletion before adoptive transfer of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes for patients with metastatic melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 34, 2389–2397 (2016).

Besser, M. J. et al. Minimally cultured or selected autologous tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes after a lympho-depleting chemotherapy regimen in metastatic melanoma patients. J. Immunother. 32, 415–423 (2009).

Besser, M. J. et al. Clinical responses in a phase II study using adoptive transfer of short term cultured tumor infiltration lymphocytes in metastatic melanoma patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 16, 2646–2655 (2010).

Whilding, L. M., Vallath, S. & Maher, J. The integrin αvβ6: a novel target for CAR T-cell immunotherapy? Biochem. Soc. Trans. 44, 349–355 (2016).

Wang, W. et al. Specificity redirection by CAR with human VEGFR-1 affinity endows T lymphocytes with tumor-killing ability and anti-angiogenic potency. Gene Ther. 20, 970–978 (2013).

Mikucki, M. E. et al. Non-redundant requirement for CXCR3 signalling during tumoricidal T-cell trafficking across tumour vascular checkpoints. Nat. Commun. 6, 7458 (2015).

Stewart, M. D. & Sanderson, R. D. Heparan sulfate in the nucleus and its control of cellular functions. Matrix Biol. 35, 56–59 (2014).

Caruana, I. et al. Heparanase promotes tumor infiltration and antitumor activity of CAR-redirected T lymphocytes. Nat. Med. 21, 524–529 (2015).

Sakaguchi, S., Miyara, M., Costantino, C. M. & Hafler, D. A. FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in the human immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 10, 490–500 (2010).

Bollard, C. M. et al. Adapting a transforming growth factor beta-related tumor protection strategy to enhance antitumor immunity. Blood 99, 3179–3187 (2002).

Toyokuni, S., Okamoto, K., Yodoi, J. & Hiai, H. Persistent oxidative stress in cancer. FEBS Lett. 358, 1–3 (1995).

Kono, K. et al. Decreased expression of signal-transducing zeta chain in peripheral T cells and natural killer cells in patients with cervical cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2, 1825–1828 (1996).

Kono, K. et al. Hydrogen peroxide secreted by tumor-derived macrophages down-modulates signal-transducing zeta molecules and inhibits tumor-specific T cell-and natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Eur. J. Immunol. 26, 1308–1313 (1996).

Ligtenberg, M. A. et al. Coexpressed catalase protects chimeric antigen receptor-redirected T cells as well as bystander cells from oxidative stress–induced loss of antitumor activity. J. Immunol. 196, 759–766 (2016).

Leen, A. M. et al. Reversal of tumor immune inhibition using a chimeric cytokine receptor. Mol. Ther. 22, 1211–1220 (2014).

Mohammed, S. et al. Improving chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cell function by reversing the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment of pancreatic cancer. Mol. Ther. 25, 249–258 (2017).

Wilkie, S. et al. Selective expansion of chimeric antigen receptor-targeted T-cells with potent effector function using interleukin-4. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 25538–25544 (2010).

Zhang, L. et al. Improving adoptive T cell therapy by targeting and controlling IL-12 expression to the tumor environment. Mol. Ther. 19, 751–759 (2011).

Chmielewski, M., Kopecky, C., Hombach, A. A. & Abken, H. IL-12 release by engineered T cells expressing chimeric antigen receptors can effectively muster an antigen-independent macrophage response on tumor cells that have shut down tumor antigen expression. Cancer Res. 71, 5697–5706 (2011).

Kulemzin, S. V., Kuznetsova, V. V., Mamonkin, M., Taranin, A. V. & Gorchakov, A. A. CAR T-cell therapy: balance of efficacy and safety]. Mol. Biol. 51, 274–287 (2017).

Brentjens, R. J. et al. CD19-targeted T cells rapidly induce molecular remissions in adults with chemotherapy-refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 5, 177ra138 (2013).

Davila, M. L. & Sadelain, M. Biology and clinical application of CAR T cells for B cell malignancies. Int. J. Hematol. 104, 6–17 (2016).

Morgan, R. A. et al. Case report of a serious adverse event following the administration of T cells transduced with a chimeric antigen receptor recognizing ERBB2. Mol. Ther. 18, 843–851 (2010).

Ertl, H. C. et al. Considerations for the clinical application of chimeric antigen receptor T cells: observations from a recombinant DNA advisory committee symposium held June 15, 2010. Cancer Res. 71, 3175–3181 (2011).

Maus, M. V. et al. T cells expressing chimeric antigen receptors can cause anaphylaxis in humans. Cancer Immunol. Res. 1, 26–31 (2013).

Beatty, G. L. et al. Mesothelinspecific chimeric antigen receptor mRNA-engineered T cells induce anti-tumor activity in solid malignancies. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2, 112–120 (2014).

Sadelain, V. D., Kloss, M. & Novel, C. C. approaches to enhance the specificity and safety of engineered T cells. Cancer J. 20, 160–165 (2014).

Sadelain, M. Chimeric antigen receptors: driving immunology towards synthetic biology. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 41, 68–76 (2016).

Grada, Z. et al. TanCAR: a novel bispecific chimeric antigen receptor for cancer immunotherapy. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2, e105 (2013).

Butte, M. J., Keir, M. E., Phamduy, T. B., Sharpe, A. H. & Freeman, G. J. Programmed death-1 ligand 1 interacts specifically with the B7-1 costimulatory molecule to inhibit T cell responses. Immunity 27, 111–122 (2007).

Fedorov, V. D., Themeli, M. & Sadelain, M. PD-1- and CTLA-4-based inhibitory chimeric antigen receptors (iCARs) divert off-target immunotherapy responses. Sci. Transl. Med. 5, 215ra172 (2013).

Ellis, J. Silencing and variegation of gammaretrovirus and lentivirus vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 16, 1241–1246 (2005).

Witting, S. R., Vallanda, P. & Gamble, A. L. Characterization of a third generation lentiviral vector pseudotyped with Nipah virus envelope proteins for endothelial cell transduction. Gene Ther. 20, 997–1005 (2013).

Schröder, A. R. W. et al. HIV-1 integration in the human genome favors active genes and local hotspots. Cell 110, 521–529 (2002).

Bushman, F. et al. Genome-wide analysis of retroviral DNA integration. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 848–858 (2005).

De Palma, M. et al. Promoter trapping reveals significant differences in integration site selection between MLV and HIV vectors in primary hematopoietic cells. Blood 105, 2307–2315 (2005).

June, C. H., Blazar, B. R. & Riley, J. L. Engineering lymphocyte subsets: tools, trials and tribulations. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 704–716 (2009).

Shayakhmetov, D. M., Di Paolo, N. C. & Mossman, K. L. Recognition of virus infection and innate host responses to viral gene therapy vectors. Mol. Ther. 18, 1422–1429 (2010).

Nayak, S. & Herzog, R. W. Progress and prospects: immune responses to viral vectors. Gene Ther. 17, 295–304 (2010).

Hackett, P. B., Largaespada, D. A. & Cooper, L. J. A transposon and transposase system for human application. Mol. Ther. 18, 674–683 (2010).

Walisko, O. et al. Transcriptional activities of the Sleeping Beauty transposon and shielding its genetic cargo with insulators. Mol. Ther. 16, 359–369 (2008).

Moldt, B., Yant, S. R., Andersen, P. R., Kay, M. A. & Mikkelsen, J. G. Cis-acting gene regulatory activities in the terminal regions of sleeping beauty DNA transposon-based vectors. Hum. Gene Ther. 18, 1193–1204 (2007).

Chabot, S. et al. Minicircle DNA. Electrotransfer for efficient tissue-targeted gene delivery. Gene Ther. 20, 62–68 (2013).

Kobelt, D. et al. Performance of high quality minicircle DNA for in vitro and in vivo gene transfer. Mol. Biotechnol. 53, 80–89 (2013).

Monjezi, R. et al. Enhanced CAR T-cell engineering using non-viral Sleeping Beauty transposition from minicircle vectors. Leukemia 31, 186–194 (2017).

Kebriaei, P. et al. Phase I trials using Sleeping Beauty to generate CD19-specific CAR T cells. J. Clin. Invest. 126, 3363–3376 (2016).

Hegde, M. et al. Combinational targeting offsets antigen escape and enhances effector functions of adoptively transferred T cells in glioblastoma. Mol. Ther. 21, 2087–2101 (2013).

Tamada, K. et al. Redirecting gene-modified T cells toward various cancer types using tagged antibodies. Clin. Cancer Res. 18, 6436–6445 (2012).

Clémenceau, B. et al. Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) is mediated by genetically modified antigen-specific human T lymphocytes. Blood 107, 4669–4677 (2006).

Kudo, K. et al. T lymphocytes expressing a CD16 signaling receptor exert antibody-dependent cancer cell killing. Cancer Res. 74, 93–102 (2014).

Ochi, F. et al. Gene-modified human α/β-T cells expressing a chimeric CD16-CD3ζ receptor as adoptively transferable effector cells for anticancer monoclonal antibody therapy. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2, 249–262 (2014).

D’Aloia, M. M. et al. T lymphocytes engineered to express a CD16-chimeric antigen receptor redirect T-cell immune responses against immunoglobulin G-opsonized target cells. Cytotherapy 18, 278–290 (2015).

Falahi, F., Sgro, A. & Blancafort, P. Epigenome engineering in cancer: fairytale or a realistic path to the clinic? Front. Oncol. 5, 22 (2015)..

Osborn, M. J. et al. Evaluation of TCR gene editing achieved by TALENs, CRISPR/Cas9, and megaTAL nucleases. Mol. Ther. 24, 570–581 (2016).

Torikai, H. et al. A foundation for universal T-cell based immunotherapy: T cells engineered to express a CD19-specific chimeric-antigen-receptor and eliminate expression of endogenous TCR. Blood 119, 5697–5705 (2012). Erratum in: Blood. 126, 2527 (2015).

Su, S. et al. CRISPR-Cas9 mediated efficient PD-1 disruption on human primary T cells from cancer patients. Sci. Rep. 6, 20070 (2016).

Arumugam, V. et al. TCR signaling intensity controls CD8+ T cell responsiveness to TGF-β. J. Leukoc. Biol. 98, 703–712 (2015).

Sadelain, M., Papapetrou, E. P. & Bushman, F. D. Safe harbours for the integration of new DNA in the human genome. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 51–58 (2011).

Bakema, J. E. & Van Egmond, M. Fc receptor-dependent mechanisms of monoclonal antibody therapy of cancer. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 382, 373–392 (2014).

Braster, R., O’Toole, T. & Van Egmond, M. Myeloid cells as effector cells for monoclonal antibody therapy of cancer. Methods 65, 28–37 (2014).

Rogers, L. M., Veeramani, S. & Weiner, G. J. Complement in monoclonal antibody therapy of cancer. Immunol. Res. 59, 203–210 (2014).

James, A. M., Cohen, A. D. & Campbell, K. S. Combination immune therapies to enhance anti-tumor responses by NK cells. Front. Immunol. 4, 481 (2013)..

Simpson, T. R. et al. Fc-dependent depletion of tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells co-defines the efficacy of anti–CTLA-4 therapy against melanoma. J. Exp. Med. 210, 1695–1710 (2013).

Frey, D. M. et al. High frequency of tumor-infiltrating FOXP3(+) regulatory T cells predicts improved survival in mismatch repair-proficient colorectal cancer patients. Int. J. Cancer 126, 2635–2643 (2010).

Sconocchia, G. et al. Tumor infiltration by FcγRIII (CD16)+myeloid cells is associated with improved survival in patients with colorectal carcinoma. Int. J. Cancer 128, 2663–2672 (2011).

Sconocchia, G. et al. HLA class II antigen expression in colorectal carcinoma tumors as a favorable prognostic marker. Neoplasia 16, 31–42 (2014).

Van Allen, E. M. et al. Genomic correlates of response to CTLA-4 blockade in metastatic melanoma. Science 350, 207–211 (2015).

Koster, B. D., de Gruijl, T. D. & van den Eertwegh, A. J. Recent developments and future challenges in immune checkpoint inhibitory cancertreatment. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 27, 482–488 (2015).

Weijtens, M. E., Willemsen, R. A., Valerio, D., Stam, K. & Bolhuis, R. L. Single chain Ig/gamma gene-redirected human T lymphocytes produce cytokines, specifically lyse tumor cells, and recycle lytic capacity. J. Immunol. 157, 836–843 (1996).

Zhang, C. et al. Phase I escalating-dose trial of CAR-T therapy targeting CEA(+) metastatic colorectal cancers. Mol. Ther. 25, 1248–1258 (2017).

Katz, S. C. et al. Phase I hepatic immunotherapy for metastases study of intra-arterial chimeric antigen receptor-modified T-cell therapy for CEA+ liver metastases. Clin. Cancer Res. 21, 3149–3159 (2015).

Feng, K. C. et al. Cocktail treatment with EGFR-specific and CD133-specific chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in a patient with advanced cholangiocarcinoma. J. Hematol. Oncol. 10, 4 (2017).

Badhiwala, J., Decker, W. K., Berens, M. E. & Bhardwaj, R. D. Clinical trials in cellular immunotherapy for brain/CNS tumors. Expert Rev. Neurother. 13, 405–424 (2013).

Morgan, R. A. et al. Recognition of glioma stem cells by genetically modified T cells targeting EGFRvIII and development of adoptive cell therapy for glioma. Hum. Gene Ther. 23, 1043–1053 (2012).

Ahmed, N. et al. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-specific chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells for the immunotherapy of HER2-positive sarcoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 1688–1696 (2015).

van Schalkwyk, M. C. I. et al. Design of a phase I clinical trial to evaluate intratumoral delivery of ErbB-targeted chimeric antigen receptor T-cells in locally advanced or recurrent head and neck cancer. Hum. Gene Ther. Clin. Dev. 24, 134–142 (2013).

Schuberth, P. C. et al. Treatment of malignant pleural mesothelioma by fibroblast activation protein-specific re-directed T cells. J. Transl. Med. 11, 187 (2013).

Kandalaft, L. E., Powell, D. J. Jr & Coukos, G. A phase I clinical trial of adoptive transfer of folate receptor-alpha redirected autologous T cells for recurrent ovarian cancer. J. Transl. Med. 10, 157 (2012).

Richman, S. A. et al. High-affinity GD2-specific CAR T cells induce fatal encephalitis in a preclinical neuroblastoma model. Cancer Immunol. Res. 6, 36–46 (2017).

Heczey, A. et al. CAR T cells administered in combination with lymphodepletion and PD-1 inhibition to patients with neuroblastoma. Mol. Ther. 25, 2214–2224 (2017).

Brown, C. E. et al. Regression of glioblastoma after chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 2561–2569 (2016).

Tanyi, J. L. et al. Possible compartmental cytokine release syndrome in a patient with recurrent ovarian cancer after treatment with mesothelin-targeted CAR-T cells. J. Immunother. 40, 104–107 (2017).

You, F. et al. Phase 1 clinical trial demonstrated that MUC1 positive metastatic seminal vesicle cancer can be effectively eradicated by modified anti-MUC1 chimeric antigen receptor transduced T cells. Sci. China Life Sci. 59, 386–397 (2016).

Koneru, M., O’Cearbhaill, R., Pendharkar, S., Spriggs, D. R. & Brentjens, R. J. A phase I clinical trial of adoptive T cell therapy using IL-12 secreting MUC-16(ecto) directed chimeric antigen receptors for recurrent ovarian cancer. J. Transl. Med. 13, 102 (2015).

Junghans, R. P. et al. Phase I trial of anti-PSMA designer CAR-T cells in prostate cancer: possible role for interacting interleukin 2-T cell pharmacodynamics as a determinant of clinical response. Prostate 76, 1257–1270 (2016).

Acknowledgements

M.A. is supported by AIRC RG 1133.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

D’Aloia, M.M., Zizzari, I.G., Sacchetti, B. et al. CAR-T cells: the long and winding road to solid tumors. Cell Death Dis 9, 282 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-018-0278-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-018-0278-6

This article is cited by

-

Advances in Engineered Macrophages: A New Frontier in Cancer Immunotherapy

Cell Death & Disease (2024)

-

Programmable synthetic receptors: the next-generation of cell and gene therapies

Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy (2024)

-

Convection-enhanced delivery of nanoencapsulated gene locoregionally yielding ErbB2/Her2-specific CAR-macrophages for brainstem glioma immunotherapy

Journal of Nanobiotechnology (2023)

-

Adoptive cellular immunotherapy for solid neoplasms beyond CAR-T

Molecular Cancer (2023)

-

CD16 CAR-T cells enhance antitumor activity of CpG ODN-loaded nanoparticle-adjuvanted tumor antigen-derived vaccinevia ADCC approach

Journal of Nanobiotechnology (2023)