Abstract

Background Over the last two decades, the introduction of equality legislation has resulted in disabled people having improved opportunities and better access to services. Within the field of oral health care, the specialty of special care dentistry exists to act as an advocate for those with disabilities and it is recognised that there is a need to reduce health inequalities. To ensure the future dental workforce is able to respond to the needs of those with disabilities, education is key. This raises the question: 'are we adequately preparing future dental professionals to fulfil their obligations?'.

Aim To explore final year dental students' insight into issues of disability in order to inform the undergraduate special care dentistry programme.

Method Qualitative methods using focus groups were employed to address the research issue. The data were analysed using thematic analysis.

Results Four main themes were identified: 'perceptions of disability', 'experience of disability', 'patient management' and 'teaching and learning'. The level of preparedness varied among students and could be attributed to: knowledge of disability issues; previous experience of people with disabilities; how education in the field of special care dentistry was delivered. Students identified the need for more structure to their teaching and increased exposure to the disabled community.

Conclusion The issues identified reflect current literature and highlight the importance of addressing disability within the wider undergraduate curriculum. Responding to the 'student voice' has the potential to tailor elements of the special care dentistry programme, in order to address their educational needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Key points

-

Suggests that final year undergraduate dental students from one UK dental school report differing levels of experience and knowledge of disability and varying degrees of preparedness and self-efficacy in meeting the needs of patients with disabilities.

-

Highlights the need for more structured education in the field of special care dentistry, with a greater emphasis on mastery experience and exposure to people with disabilities both on a clinical and community basis.

-

By sharing research frameworks and educational models, we have the potential to deliver appropriate health care services to those most vulnerable within our society.

Background

Over the last two decades, the introduction of equality legislation has resulted in disabled people having improved opportunities and better access to services. However, many individuals continue to encounter a range of challenges, often related to attitudes and behaviours within society.

It is well documented that good oral health strongly contributes to general health and therefore quality of life.1,2 The literature suggests that people living with disabilities have poorer oral health, high levels of unmet need, limited access to appropriate oral healthcare facilities,3,4 and often experience a poorer quality of life as a result. The UK Adult Dental Health Survey of 2009 reported a marked improvement in the oral health of the adult population, with more people retaining their teeth to an older age,5 and it has been predicted that further improvements will be seen as the younger generation ages. Consequently, the dental profession will be faced with a challenge to provide care for those with disabilities who will potentially present with a heavily restored dentition, but who are less able to access and cope with treatment.

The specialty of special care dentistry exists to act as an advocate for those with disabilities and NHS England has recently published a document describing the commissioning process for special care dentistry services.6 The document states that, throughout its development, due regard has been given 'to the need to reduce inequalities between patients in access to, and outcomes from, healthcare services and to ensure services are provided in an integrated way where this might reduce health inequalities'.6

The use of care pathways to promote organised and efficient patient care is highlighted with three levels of case complexity being described; level one is of particular relevance, in that it is described as 'special care needs that require a skill set and competence as covered by dental undergraduate training and dental foundation training.' Delivery of care at this level relies on appropriate undergraduate training and the document stresses:

'To enable members of dental teams to meet the competencies required at level one to provide care for patients with special care needs, it is important that dental schools incorporate special care dentistry within their curricula as a specific specialty subject'.

Education is key to preparing the future dental workforce to respond to the needs of those with disabilities and it is important we assess students' sense of preparedness to better understand their development needs. Many of the studies carried out to consider preparedness in the field of special care dentistry have relied on quantitative methods using questionnaires asking students to rate how confident they feel. This methodology, however, is unable to capture insight and feelings which all contribute to a more holistic view of the students' experiences.

Using qualitative methods such as focus groups, it is possible to capitalise on the communication and discussion between participants providing context and a deeper understanding of the phenomenon being studied.7,8 As such, a pilot study was designed to explore final year dental students' insight into issues of disability, perceptions of their preparedness to meet the needs of patients with disabilities, and what factors had influenced this sense of preparedness.

Aim

To explore final year dental students' insight into issues of disability, in order to inform the undergraduate special care dentistry programme.

Research questions

-

1.

What are students' perceptions of their preparedness to meet the needs of patients with disabilities?

-

2.

What has influenced this sense of preparedness?

Method

The study was conducted at the University of Newcastle, School of Dental Sciences, in December 2016 and received ethical approval from the Faculty of Medical Sciences Research Office (1219/2015).

Research team

The research team included three university staff members and a final year dental student. The dental student was invited onto the team to contribute the views of their peers into the design, running and analysis of the study.

Study design

Focus groups were chosen as the method of data collection, as they provide a social context within which the phenomenon is viewed, capitalising on the communication and discussion between participants.7,8

Sampling strategy

Non-probability, 'purposive' sampling was used. As the work sought to determine how prepared students felt about dealing with those with disabilities once qualified, the final year group were considered to be at an appropriate stage to reflect on this issue and thus provided the sample frame. All 82 undergraduate final year dental students were emailed initial study information and asked to contact the principle investigator if interested. Every effort was made to select participants from different study groups and of different gender. The students selected were provided with a detailed participant information sheet and written consent was gained.

Sample size

There are no statistical grounds for determining focus group sample size; the ideal size is five to eight people.8 The intention for this study was to recruit at least seven participants for each focus group.

Running the focus groups

Developing a topic guide

The primary researcher (author), along with three members of the research team, were instrumental in developing the topic guide which would act to guide the discussion (Box 1).

Conducting the focus group

The primary researcher acted as the group facilitator and the research team final year dental student acted as an observer. Owing to time constraints, a maximum of two focus groups were planned, to be carried out at a convenient location/time for the students. Stages of the group process are illustrated in Figure 1. Both groups were audio recorded to provide a verbatim record; all data were stored securely on a password-protected computer file.

Data analysis

A professional transcriber was employed to transcribe the audio recordings. The transcripts were then reviewed using the process of thematic analysis, as described by Braun and Clarke.9 This was initially carried out independently by three members of the research team; a meeting was then held to deal with any conflicting views. This was an iterative process, being repeated two further times until the final sub-themes and themes were agreed.

Results

Demographics

Of the 82 final year dental students at Newcastle School of Dental Sciences, a total of 16 took part in the study. The final year cohort is split into ten study groups; seven participants, three male and four female, with representatives for study groups 1, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 9, were involved in focus group one. Focus group two included nine participants, one male and eight females from study groups 2, 3, 4, 5, 7 and 10 (Fig. 2).

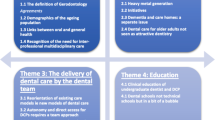

Emergent themes

Following analysis of the transcripts, four main themes emerged (Table 1). The sub-themes and themes are presented, supported by a selection of quotes coded by participant number to demonstrate a range of views from the majority of the students.

Theme one: perceptions of disability

Defining disability

The dental students' perceptions of disability centred around the medical model where a person's disability is used to define them and the impairment is seen as the problem:

'A person that's less able than a normal person… that may be a physical problem or it may be a mental problem' (P2).

Some participants believed disability to be physical or mental with little reference to the broader definition:

'I was going to say it's probably any impairment that affects someone's day-to-day life, be it physical or mental' (P8);

'Like an impairment of some kind, like participant number two says, physical or mental' (P5).

There was an acknowledgement that disability affects not only the individual but also has an impact on those acting as carers:

'For me, there's the disability side but then there's also the carer's side and how far they are affected by things' (P6).

Social and equality issues

Some believed society still views disability from a negative perspective, whilst others felt that there is a greater recognition of the need to be more inclusive, recognising the need for equality amongst vulnerable groups:

'So I think a lot of society perceive it as something like really unnerving and don't know how to act around it or how to treat people' (P13);

'It's becoming more common in society and people are becoming more accepting of it' (P14).

Theme two: experience of disability

Social setting

Participants reported experience of disability through voluntary work, having a relative with a disability, or through the media. These students appeared to have a level of insight into issues relating to disability and an empathy for the impact on the individual and their families:

'My school has a partnership with a local special needs school…. the girl I was partnered with, she had global development delay. She had very poor communication. And at first I didn't really know how to interact with her and I found it quite uncomfortable…. it was only when we were given that time alone that I felt able to give it a go' (P10).

Clinical setting

The level of clinical experience relating to disability varied amongst students and those who had experience reported the positive effect this had on their level of comfort in dealing with this patient group:

'I got a patient who was physically disabled and also had early dementia... and so I was quite intimidated when I first had to treat that patient and I think having a bit of experience with her made me more comfortable, but it was quite an issue for me to begin with' (P5).

Theme three: patient management

Professional responsibility

There was a general sense that dentists have a professional responsibility to address the oral health needs of all patient groups without discrimination and an acknowledgement that undergraduates need to learn about dealing with a wide range of patients, including those with disabilities:

'I think that everyone should have the right to get dental treatment…. Someone said to me that toothache is the world's greatest equaliser because it's a constant pain that can affect everyone…. I think we can have a role in making sure that everyone's treated appropriately' (P7);

'I think you have to be very open to the idea that your patients could be from anywhere because, if not, it's basically a type of prejudice' (P14).

Preparedness

The sense of preparedness was very variable; some students expressed concern and discomfort about the prospect of treating patients requiring special care, voicing strong feelings about this:

'If I was given someone with a severe learning difficulty or mental disability or someone who came in in a wheelchair I wouldn't be comfortable. I wish I could say, "Oh yeah, this is going to be really easy. I know how to deal with this."' (P14).

Whilst others indicated they would look forward to and be comfortable in managing such patients:

'I've had quite a lot of experience with it so I'm quite comfortable' (P13).

Issues influencing perceptions of preparedness

Discomfort with providing patient care was linked to a lack of confidence in knowing how to communicate effectively with patients and their carers:

'you feel a bit lost… when you're communicating with [learning disability patients], what their understanding level is. So you don't know' (P12);

'I guess communication …. with cerebral altered speech you might struggle more with understanding the patient, possibly' (P14).

The anticipated time pressures of general dental practice were also identified as being an influencing factor, with the acknowledgement that, in general practice, time may be limited due to the requirement to deliver quotas and units of dental activity, if working in England and Wales:

'I think time as well might be a factor, I think probably linked to communication about how long you can spend with people' (P3);

'I think the time thing is a big influence on special care' (P13).

Theme four: teaching and learning

Barriers and facilitators to teaching and learning

Lack of exposure to patients with disabilities was quoted as a barrier to learning:

'Without the exposure, you can learn the theories behind it but it's very hard to put into practice' (P4);

'I think it's very rare that you do get that kind of exposure in the dental hospital' (P7).

Students believed they would benefit from more exposure to patients with disabilities through shadowing on special care clinics in the outreach clinics with experienced staff from the community dental service:

'I think yes, shadowing seems like a really good idea… I think just seeing more experienced people and how they deal with it really can help in you being able to pick up ideas and tips and things' (P5).

Linking with disability groups in the community was raised as a means of engaging with society and learning about the broader issues of the needs of patients:

'So maybe forming more links in the community with others' (P12).

Small group seminars involving people with disabilities were felt to be a useful way of learning about specific impairments and gaining opinions of what patients want:

'To get people in with disabilities, they could tell you how they would want a dentist appointment to run' (P1).

Discussion

The overall aim of this research study was to explore students' insight into the issues of disability and to consider how prepared they felt for clinical practice in the field of special care dentistry. Having insight into the needs of those with special care requirements may play a key role in how students approach patient care. Through the theme 'perceptions about disability', this issue was explored and it became apparent that students' views about disability were varied, many centring on the medical model, identifying disability as being the individual's problem, with limited reference being made to society's role in disabling rather than enabling those with impairments: 'a person that's less able than a normal person… that may be a physical problem or it may be a mental problem'.

Some participants did, however, show greater insight into the social aspects of disability and the wider implications of how society approaches disability, with the discussion developing to focus on the importance of 'enabling' people with disabilities. This challenged the participants to consider their professional responsibilities, and there was a strong sense that all members of society had a right to equality in the provision of health services.

Having identified their professional obligations, the students were encouraged to consider how prepared they felt with regard to the reality of meeting these obligations in relation to those with disabilities. Ali et al. stress that the sense of preparedness will be greatly influenced by the individual's own self-efficacy;10 without this, students may be more likely to perceive themselves as being less well prepared. Self-efficacy beliefs, described by Bandura11 as: 'people's judgements of their capabilities to organise and execute courses of action required to attain designated types of performances', can provide a useful measure alongside more formal assessment methods.

It has been suggested that students with high self-efficacy choose to engage in activities supporting the development of their attitudes, knowledge and skills. By addressing students' self-efficacy, medical educators may be able to deliver more engaging and effective instruction. Sources which may influence self-efficacy have been postulated by Bandura:12

- 1.

Through 'mastery experiences' (carrying out an activity); success builds a sound belief in one's own efficacy, while failures undermine it

- 2.

'Vicarious experiences', in the form of watching others succeed, influences the observer's belief that they too are capable of the activity

- 3.

'Social persuasion' where the individual is influenced by positive feedback

- 4.

In order to increase self-efficacy, 'reducing peoples' stress reactions' to situations, will have a positive influence.

In answering the research questions, it was noted that there was variation in students' perceptions regarding their preparedness and self-efficacy related to several influencing factors linked to the emergent themes: 'perceptions about disability', 'experience of disability', 'patient management' and 'teaching and learning'. Elements of each will be drawn upon and woven together during the formative years from undergraduate to practising clinician, influencing the extent of self-efficacy beliefs and how prepared students feel about meeting the needs of those with disabilities.

Considering this issue in context of the focus group discussions, there appeared to be marked variation in students' sense of self-efficacy, suggesting that not all would necessarily attempt to meet their obligations. Some believed they would have the ability to care for those with disabilities whilst some believed they would be out of their comfort zone and lacking in confidence. These issues are further explored by considering the second research question.

What has influenced students' sense of preparedness?

In considering the students' views regarding what had influenced their sense of preparedness, links can be made between the emergent study themes and Bandura's theory of self-efficacy.11

Mastery experiences

The students identified where they had had personal experience of people with disabilities, be it in a social, clinical or educational context; this provided them with a foundation on which to build their knowledge and skills. Here the 'mastery experience' component of Bandura's theory has been raised as an important element of personal development: 'I've had quite a lot of experience with it so I'm quite comfortable'.

This echoes the dental literature, where it has been suggested that exposure to people with disabilities is a major factor influencing students' intentions to care for vulnerable groups; more favourable attitudes towards those with physical disabilities were associated with greater professional and social experience of these people.13,14,15

Leading on from this, an interesting reflection emerging in the later stages of the focus group discussion was the benefit of engaging with disability groups within the community. Such interaction was considered valuable in learning more about the social as well as clinical needs of vulnerable groups, demonstrating insight into the broader issues of disability awareness: 'so maybe forming more links in the community with others'.

Vicarious experiences

By watching others succeed individuals generate efficacy beliefs that they too can attain the ability to be successful. The opposite, however, may be true; where seeing others struggle in a situation may lower the observer's opinion of their own efficacy.16 The students in the current study identified the benefit of such opportunities in the form of shadowing experienced clinicians. They recognised the importance of reflecting on how different clinicians approached patient management and communication:

'I think yes, shadowing seems like a really good idea… I think just seeing more experienced people and how they deal with it really can help in you being able to pick up ideas and tips and things'.

Considered a valuable educational platform, it was believed watching and learning from others had enabled them to gain a deeper understanding of the challenges of communication, access issues and treatment provision.

Social persuasion

Verbal persuasion or feedback from others, although considered a weaker influence on self-belief, has been quoted to be widely used in academic environments to assist students in believing that they can cope with challenging situations.17 This source was recognised by the students as being an important aspect of their development, alongside experience and vicarious learning. How a student processes and interprets feedback, however, will influence their learning and impact on their self-development; constructive comments have the potential to foster strong self-efficacy, whilst negative support can diminish an individual's drive to improve.

Other influences

Linking into the theme of 'teaching and learning', identifying where special care dentistry sits within the undergraduate curriculum and understanding how it is delivered, were identified by participants as influencing factors in preparing them for practice. A lack of structured education at undergraduate level can lead to graduates feeling less able to address patient needs and has been cited as a barrier to the delivery of care to those with disabilities.17,18,19,20 Didactic teaching was not considered greatly beneficial by some students. Much greater importance was placed on experiential learning through interacting with patients and carers, in line with the theory that mastery experience greatly enhances self-efficacy beliefs, as discussed above.

Credibility of study

To ensure credibility of the findings several provisions were made:7

- 1.

Adoption of well-established research methods in the form of focus groups

- 2.

Data source triangulation, with similar viewpoints emerging from each focus group

- 3.

Peer scrutiny was achieved through the primary researcher being supported by a research team

- 4.

Member checking was carried out, seeking comments from participants on the accuracy of the findings.

Limitations of the work

-

1.

The main author and focus group facilitator was a senior member of staff with a particular interest in disability issues which may have influenced participants' responses

-

2.

Approximately one quarter of the final year group showed an interest in taking part in the study; reasons the other students did not volunteer were not sought

-

3.

Opinions were not gathered from patients themselves, who may have opinions on how prepared they believe students to be

-

4.

The focus of this study was dental undergraduate training and limited to a particular group of students at one university, it is therefore not possible to generalise the findings

-

5.

Another group who may have contributed are the clinical teachers and, again, they were not involved in the current study.

Conclusion

By using focus groups to discuss experiences, perspectives and behaviours around disability amongst final year dental students at Newcastle University, it was anticipated that ideas for developing the delivery of the special care dentistry curriculum could be generated. It is accepted that this was a pilot study and, as such, the data generated was limited. However, as all participants were consumers of, and actively engaged in, dental education, and had shown particular interest in the topic of disability, the assumption was that data generated would be valuable and transparent.

The results of the study resonate with the majority of the literature in that students reported different levels of experience and knowledge of disability, and varying degrees of preparedness and self-efficacy in meeting patients' needs. Closely aligned to Bandura's theory of self-efficacy,16 which considers 'mastery experience' to be the most powerful influence of efficacy beliefs, students who had encountered people with disabilities at a social level, through volunteering, family or friends, had a strong sense of self-efficacy. Added to this, if clinical exposure was reported, students again felt more comfortable dealing with this patient group. All agreed that the benefits of social and or clinical interaction with the disabled community would greatly enhance their professional development.

By sharing research frameworks and educational models, we have the potential to deliver appropriate health care services to those most vulnerable within our society, and as stated in Article 1 of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: 'to ensure the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms by all persons with disabilities, and to promote respect for their inherent dignity'.21

Recommendations

To enhance preparedness and self-efficacy in meeting the needs of those with disabilities, the main area highlighted by the students was the value and importance of exposure to people with disabilities. As such, the following recommendations may be valuable when reviewing delivery of the special care dentistry curriculum at Newcastle University and future research:

- 1.

Increase exposure to the management of patients with disabilities through, for example, shadowing experienced clinicians or accessing online resources

- 2.

Develop links with disability groups within the community

- 3.

Organise small group seminars involving patients with disabilities.

References

Sheiham A. Oral health, general health and quality of life. 2005. Available at http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/83/9/editorial30905html/en/ (accessed June 2019).

Sharma, P, Busby, M, Chapple, L, Matthews, R, Chapple I. The relationship between general health and lifestyle factors and oral health outcomes. Br Dent J 2016; 221: 65-69.

Coyle C, Saunderson W, Freeman R. Dental students, social policy students and learning disability: do differing attitudes exist? Eur J Dent Educ 2004; 8: 133-139.

Ahmad M S, Razak I A, Borromeo G L. Special needs dentistry: perception, attitudes and educational experience of Malaysian dental students. Eur J Dent Educ 2015; 19: 44-52.

Steele J G, Treasure E T, O'Sullivan I, Morris J, Murray J J. Adult Dental Health Survey 2009: transformations in British oral health 1968-2009. Br Dent J 2012; 213: 523-527.

NHS England. Guides for commissioning dental specialties - Special Care Dentistry. London: NHS England, 2015. Available at https://www.england.nhs.uk/commissioning/wp-content/uploads/sites/12/2015/09/guid-comms-specl-care-dentstry.pdf (accessed June 2019).

Kitzinger J. Qualitative research. introducing focus groups. BMJ 1995; 311: 299-302.

Krueger R A, Casey M A. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. 4th ed. London: Sage, 2009.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psych 2006; 3: 77-101.

Ali K, Tredwin C, Kay E J, Slade A, Pooler J. Preparedness of dental graduates for foundation training: a qualitative study. Br Dent J 2014; 217: 145-149.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychol Rev 1977; 84: 191-215.

Bandura A. Self Efficacy. In Ramachaudran S (ed) Encyclopedia of Human Behavior. pp. 71-81. New York: Academic Press, 1994.

Oredugba F A, Akinwande J A. Preparedness of dental undergraduates for provisio of care to individuals with special health care needs in Nigeria. J Disabil Oral Health 2008; 9: 81-86.

Satchidanand N, Gunukula S K, Lam W Y et al. Attitudes of healthcare students and professionals toward patients with physical disability: a systematic review. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2012; 91: 533-545.

Yeaton S, Moorthy A, Rice J et al. Special care dentistry: how prepared are we? Eur J Dent Educ 2016; 20: 9-13.

Artino A R Jr. Academic self-efficacy: from educational theory to instructional practice. Perspect Med Educ 2012; 1: 76-85.

Casamassimo P S, Seale N S, Ruehs K. General dentists' perceptions of educational and treatment issues affecting access to care for children with special health care needs. J Dent Educ 2004; 68: 23-28.

Dao L P, Zwetchkenbaum S, Inglehart M R. General dentists and special needs patients: does dental education matter? J Dent Educ 2005; 69: 1107-1115.

Kleinert H L, Sanders C, Mink J et al. Improving student dentist competencies and perception of difficulty in delivering care to children with developmental disabilities using a virtual patient module. J Dent Educ 2007; 71: 279-286.

Faulks D, Freedman L, Thompson S, Sagheri D, Dougall A. The value of education in special care dentistry as a means of reducing inequalities in oral health. Eur J Dent Educ 2012; 16: 195-201.

United Nations. Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities: Article 1 - Purpose. 2008. Available at https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities/article-1-purpose.html (accessed June 2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wilson, K., Dunn, K., Holmes, R. et al. Meeting the needs of patients with disabilities: how can we better prepare the new dental graduate?. Br Dent J 227, 43–48 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-019-0462-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41415-019-0462-9