Abstract

Study design

While clinicians who care for patients with spinal cord injury may experience heightened levels of workplace stress related to secondary trauma, little is known about the characteristics of burnout and potential protective factors among interdisciplinary professionals who care for this distinct clinical population. An online survey of self-reported burnout symptoms and meaning in work was conducted to assess the prevalence of burnout and characteristics of meaning in work among spinal cord injury professionals.

Objectives

To assess symptoms of professional burnout and meaning in work among a broad-ranging cohort of spinal cord injury clinicians and researchers.

Setting

A group of international spinal cord injury professionals.

Methods

An online survey was developed using commonly assessed metrics of burnout and meaning in work based upon prior literature.

Results

A majority of survey respondents reported feeling exhaustion (60.1%), while fewer reported feelings of burnout (41.1%) or work-life imbalance (31.9%). Many respondents found support in personal relationship from friends and family and reported using various strategies to deal with work stress, including exercise, meditation, and engaging in personally meaningful activities outside of work.

Conclusions

Exhaustion is a prevalent issue for many spinal cord injury professionals and burnout appears to be a significant issue for a subset of responders, yet despite potential workplace stressors, spinal cord injury professionals reported high meaningfulness of work, positive impact from colleagues, and satisfaction with intellectual stimulation at work.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Caring for individuals with spinal cord injury (SCI) can be both rewarding and demanding. Clinicians who care for people with SCI are often subject to secondary traumatic stress—the phenomenon of strong emotional reactions that occur due to exposure to patients’ traumatic experiences [1, 2]. They are also in a position of supporting patients and families who are facing challenging and unexpected circumstances. These specific characteristics of SCI Medicine place clinicians caring for individuals with injuries at high risk for burnout—a syndrome characterized by emotional exhaustion, loss of meaning or purpose in work, and depersonalization [3, 4]—yet no one to date has studied burnout among this group of professionals.

Burnout among physicians has been shown to adversely affect the quality of care and professionalism, and has been associated with anxiety, depression, suicide, and substance abuse among health care providers, although these observed relationships remain incompletely understood [4,5,6,7,8]. Research also suggests that physicians who experience burnout are more likely to reduce their work hours and/or pursue early retirement, with important possible implications for the healthcare workforce [9,10,11]. Little is known about personal and professional characteristics associated with burnout among clinicians who care for individuals with SCI, nor has the impact of burnout on these people’s lives been quantified. As burnout has increasingly been recognized as a critical factor affecting health care providers and their patients, accurate estimates of burnout prevalence may have important implications for the specialty of SCI Medicine. This study is the first to examine burnout among an international cohort of physician and non-physician clinicians who care for patients with SCI. We hope the results will spur and inform future research efforts.

Methods

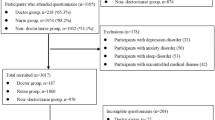

Three of the 5 co-authors (CS, SA, and CH) developed an online survey of 20 questions meant to evaluate and quantify to which degree a set of demographic and professional characteristics are associated with clinician burnout. Items were selected based upon review of existing burnout surveys [12] and the authors’ own experiences in clinical practice. The survey was posted to an internet-based platform (SurveyMonkey Inc, San Mateo, CA, www.surveymonkey.com) and distributed to our colleagues in SCI Medicine and to members of several international SCI professional organizations, including the International Spinal Cord Society (ISCoS). Respondents had access to the survey from September 2017 through January 2018, no identifying information was collected, and consent was implied by subjects’ participation. No institutional review or permission was sought or obtained, and none was considered necessary.

Descriptive analyses were performed, and in certain cases, answers were grouped in order to provide sufficient “n” for analysis. For instance, Question 2 (see Appendix) queried respondents’ profession, and as the vast majority were physicians, nurses, physical therapists, and occupational therapists, answers were grouped into 3 categories of “Physician,” “Nurse,” and “Therapist.” Certain questions utilized a 5-point Likert Scale to indicate the degree to which participants agreed with given statements (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). For analysis, answers were then collapsed into three categories (1–2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, and 4–5 = agree). Similarly, answers from those questions using a 10-point Likert Scale (0 = highly dissatisfied, 10 = highly satisfied) were collapsed into three categories (0–3 = dissatisfied, 4–6 = neutral, and 7–10 = satisfied). Ordinal ratings were utilized to facilitate straightforward responses regarding quantitative measures of meaning and burnout, with the additional option of collecting open-ended responses for specific descriptions and qualitative characteristics.

Results

Two hundred and forty-four respondents completed the survey. One hundred and eighty four respondents (75.4%) were identified as female, 60 (24.6%) as male, and nearly all were physicians (36.5%), nurses (20.1%), physical therapists (18.9%), or occupational therapists (11.5%). Among the physician subjects, 72.9% had trained in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 11% in Neurology, 5.1% in Urology, and 5.1% in Orthopedics. An additional 12 respondents (0.5% of entire sample) worked as psychologists, social workers, and personal care attendants. Nearly all respondents came from developed countries, with just over two-thirds (67.2%) living in Australia, New Zealand, the United States, the United Kingdom, or South Africa.

The average age of participants was 46.2 years, 15.9 years had passed since they had completed professional training, and they had worked an average of 12.2 years with individuals with SCI. When asked for how many additional years they expect to work, the average response was 18 with a range of 0–40. Participants reported spending an average of 10 h each week in direct patient care, 9 h performing administrative work, 5 h in research, and 6 h in teaching and educational efforts.

Participants were asked to describe their level of satisfaction with various aspects of their lives, with 1 representing the lowest and 10 representing the highest ratings, respectively (Table 1; 0–3 = dissatisfied, 4–6 = neutral, and 7–10 = satisfied). Highest satisfaction was derived from meaningfulness of work (7.59), housing (7.39), and family life (7.33) and lowest satisfaction was derived from ability to participate in recreational or entertaining activities (6.22), engagement in hobbies (5.87), being able go on vacations (5.87), and religious or spiritual life (5.36). Participants were asked using a similar scale to rate the extent to which specific aspects of their jobs impacted their professional satisfaction (Table 2; 0–3 = negative, 4–6 = neutral, and 7–10 = positive). Highest scores were ascribed to workplace colleagues (7.0) and commute to work (6.42) while the lowest scores were ascribed to the risk of being sued (3.82), using paper health records (4.7), and insurance/payment regulations (4.34). When subjects were asked to use a 5-point Likert Scale to indicate degree of agreement (1–2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, and 4–5 = agree) with statements about burnout, mean answers indicated overall neutrality (3.47 for “I am exhausted,” 3.11 for “I feel burned out,” and 3.08 for “I feel like my life is out of balance”), though sizable proportions agreed with each statement. Overall, 60.1% of respondents agreed with the statement “I am exhausted,” 41.1% agreed with the statement “I feel burned out,” and 31.9% agreed with the statement “I feel like my life is out of balance” (Table 3).

Respondents were asked if they took part in one or more activities to assist them to feel better in their lives. Many reported participating in exercise (79.2%), with far fewer engaging in meditation (27.0%), yoga or tai chi (22.6%), counseling (20.4%), writing or journaling (15.49%), and spending time with family or friends (3.5%). Of note, 21.7% reported having cut their work hours, and 13.3% reported that they did not participate in any activities to help reduce stress.

Neither profession (physician, nurse, or therapist) nor the country of origin was associated with self-reports of burnout. As expected, respondents who felt burned out were more likely than those who did not to feel dissatisfied with their work lives (Table 1), to feel exhausted (χ2 (4, N = 244) = 113.09, p < 0.001), and to feel that their lives are out of balance (χ2 (4, N = 244) = 78.72, p < 0.001). However, they were also significantly more likely to feel dissatisfied with their marriages or significant relationships, their family lives, their ability to sleep, their health, their financial situations, and their level of stimulation (Table 2). They were also more likely to identify a number of aspects of their jobs as negatively affecting their feelings toward work, including their salary, their use of paper health records, insurance regulations, and their risk of being sued (Table 3). Finally, while feeling burned out was not associated with participating in physical or leisurely activities that may mitigate stress, respondents who were burned out were more likely than those who were not to have gone for counseling (28.7% vs 14.9%; χ2 (2, N = 244) = 7.16, p = 0.028).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate symptoms of burnout and perceptions of meaning in work in an international cohort of physician and non-physician SCI clinicians. The clinicians in our survey sample had neutral responses, on average, to the statements “I am exhausted,” “I feel burned out,” and “I feel like my life is out of balance,” and reported high perceptions of meaningfulness for their work and satisfaction with intellectual stimulation and high positive impact from colleagues and the work environment. While a majority of respondents (60.1%) in this survey reported exhaustion, fewer endorsed burnout (41.1%) or work-life imbalance (31.9%). On average, respondents found support in personal relationship from friends and family and reported using various strategies to deal with work stress, including exercise, meditation, and engaging in personally meaningful activities outside of work. A subset of respondents reported not participating in any activities to help them deal with stress in their professional work life.

Burnout among health care providers has been characterized in contemporary medical literature as a complex phenomenon with likely multifactorial personal, environmental, and context-specific risk factors. While diverse factors such as administrative burden, electronic medical record (EHR) systems, team-based interactions, and support at work and at home have been hypothesized to play contributing roles, much-published data is limited by cross-sectional survey designs that preclude determinations of causality [12, 13]. By using a similar cross-sectional design, we were nonetheless able to describe several important associations using our survey sample. Notably, providers who endorsed feelings of burnout were more likely to report feeling dissatisfied with aspects of their personal lives (i.e., marriage, relationships, sleep, health, financial situations, and level of mental stimulation) in addition to dissatisfaction with their professional life and exhaustion. While it is possible that individuals experiencing high levels of burnout may experience downstream effects from burnout that, in turn, affect their personal lives, it is also plausible that those with higher levels of personal stress may be at greater risk of developing burnout at work.

While clinicians who care for patients with spinal cord injury may experience heightened levels of workplace stress related to secondary trauma, little is known about the characteristics of burnout and potential protective factors among interdisciplinary professionals who care for this distinct clinical population. Despite a relatively small sample size, our data suggests that burnout may be prevalent issue internationally for some SCI clinicians across disciplines, and that despite a high prevalence of exhaustion and possible experiences of secondary trauma, spinal cord injury professionals may cope with workplace stress differently than other types of health care professionals previously studied in the literature on burnout. This survey data suggests that SCI professionals also find their work highly meaningful despite potentially adverse experiences. Consistent with most published literature on burnout in health professionals [12], this survey sample utilizes a cross-sectional design and thus it is not possible to determine causality for symptoms of exhaustion and burnout, however, this may be an important area of future investigation for the SCI workforce at large.

Researchers and clinical leaders have suggested that organizational leadership and collective initiatives may both play a role in helping to mitigate and prevent burnout in physicians and health care professionals [4, 14,15,16]. Future research must focus on more clearly elucidating the potential causes of burnout for SCI professionals and the characteristics of providers who are more likely to experience burnout, as well as potentially protective factors for different disciplines within the spinal cord injury community. By gaining a fuller understanding of these factors, spinal cord injury professionals and organizations may work together to support and strengthen the workforce for generations to come through collective efforts to identify contributors to burnout in spinal cord injury professionals and reduce associated negative professional and personal consequences.

Conclusions

Exhaustion appears to be a prevalent issue for many spinal cord injury professionals internationally and burnout is a significant issue for a subset of providers in this diverse survey sample assessing self-evaluation of burnout characteristics and meaning in work. Nonetheless, a substantial portion of professionals reported neutral reactions or disagreed with questions about burnout and work-life imbalance. Despite potential workplace stressors, clinicians caring for those with spinal cord injury reported high meaningfulness of work, positive impact from colleagues, and satisfaction with their level of intellectual stimulation at work. Future endeavors by researchers and professional organizations should explore contributors to exhaustion among spinal cord injury professionals and potential strategies to lessen burnout among a subset of providers in order to cultivate a strong and resilient workforce.

References

Taylor J, Bradbury-jones C, Breckenridge JP, Jones C, Herber OR. Risk of vicarious trauma in nursing research: a focused mapping review and synthesis. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25:2768–77.

Newell JM, Nelson-gardell D, Macneil G. Clinician responses to client traumas: A chronological review of constructs and terminology. Trauma Violence Abus. 2016;17:306–13.

Bianchi R, Schonfeld IS. Defining physician burnout, and differentiating between burnout and depression-I. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1455.

Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:129–46.

Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, Dyrbye LN, Sotile W, Satele D. et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1377–85.

Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:1600–13.

Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, et al. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014;89:443–51.

Shanafelt TD, Gradishar WJ, Kosty M, et al. Burnout and career satisfaction among US oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:678–86.

Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP, Sinsky CA. Potential impact of burnout on the US physician workforce. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:1667–8.

Sinsky CA, Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, Tutty M, Shanafelt TD. Professional satisfaction and the career plans of US physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1625–35.

Swensen S, Kabcenell A, Shanafelt T. Physician-organization collaboration reduces physician burnout and promotes engagement: The Mayo Clinic Experience. J Health Manag. 2016;61:105–27.

Rotenstein LS, Torre M, Ramos MA, et al. Prevalence of burnout among physicians: a systematic review. JAMA. 2018;320:1131–50.

Burghi G, Lambert J, Chaize M, et al. Prevalence, risk factors and consequences of severe burnout syndrome in ICU. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:1785–6.

Hlubocky FJ, Back AL, Shanafelt TD. Addressing burnout in oncology: why cancer care clinicians are at risk, what individuals can do, and how organizations can respond. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2016;35:271–9.

Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, West CP. Addressing physician burnout: the way forward. JAMA. 2017;317:901–2.

Shanafelt T, Swensen S. Leadership and physician burnout: using the annual review to reduce burnout and promote engagement. Am J Med Qual. 2017;32:563–5.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Slocum, C., Stillman, M., Capron, M. et al. International survey responses from an interdisciplinary cohort of spinal cord injury clinicians assessing professional burnout and meaning in work. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 5, 59 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-019-0200-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-019-0200-1