Abstract

Introduction

Acute spinal cord injury is associated with an increased risk of thromboembolic events. Low-molecular-weight heparins are first-line medications for both the treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolism. Pharmacological prophylaxis may be indicated for high-risk patients and low-risk patients may be managed with non-pharmacological measures.

Case presentation

We report two cases of gluteal hematomas that occurred in patients with chronic spinal cord injury who were under prophylactic doses of enoxaparin at a tertiary rehabilitation hospital. There was no local trauma. The patients needed multiple surgical interventions and rehabilitation treatment was delayed.

Discussion

There is a lack of evidence to correctly estimate the thromboembolic risk in chronic spinal cord injury and the duration of prophylaxis. Over-prescription of pharmacological prophylaxis may expose patients to unnecessary risks. These patients frequently present with polypharmacy and reducing the amount of prescribed medication may begin with reducing prophylactic treatments for venous thromboembolism, which may be an overtreatment based on risk overestimation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The estimated annual incidence rate of spinal cord injuries is between 11 and 55 new cases per million people [1, 2]. Acute spinal cord injury is related to an increased risk of thromboembolic events, especially during the first eight to 12 weeks after the injury [3, 4]. Flaccid paralysis, immobility, and loss of vascular tonus may be related to this excessive risk in the acute phase [3, 5].

Current guidelines recommend starting pharmacological thromboembolic prophylaxis as soon as possible, preferably during the first 72 h from the event [6]. Indications for the duration of venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis in subacute and chronic spinal cord injury, however, are less clear [7, 8].

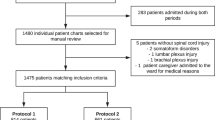

Once-daily low-molecular-weight heparin is considered a first-line treatment for VTE due to its proven safety, efficacy, and easy administration [9], but side effects may occur, even with low prophylactic doses. Bruising is common, but severe complications, such as hemorrhage or heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, may also occur [10,11,12]. We report two cases of gluteal hematoma related to prophylactic enoxaparin treatment in non-acute spinal cord patients. To our knowledge, these are the first reported cases of severe bleeding in spinal cord patients who were treated with low prophylactic doses of enoxaparin. These two cases were observed in a large rehabilitation center in Brazil in the ward for patients with spinal cord injuries, which has around 800 admissions per year. This study was approved by the Sarah Network of Rehabilitation Hospitals’ ethics committee and patient consent was obtained from both patients.

Case 1

A 25-year-old male patient was admitted for rehabilitation 9 months after a gunshot-induced thoracic spinal cord injury. He had a complete injury (AIS A) and a neurologic level at T11. He had a history of an associated traumatic splenic lesion that required splenectomy and a femoral artery laceration that required suturing in the acute phase, but no previous history of thromboembolic events. Admission for rehabilitation was delayed as the patient lived in a remote area with difficult access to rehabilitation services.

Until this admission, he hadn’t been in physical therapy or any other form of rehabilitation treatment. His upper limbs’ strength and function were normal and he reported having developed pressure ulcers on his calcanei bilaterally during the acute phase, which had completely healed by the time of his rehabilitation admission. He also reported using diazepam (10 mg) for insomnia up to four times a week. He reported no other comorbidity. The medical team decided to put him under enoxaparin prophylaxis (40 mg subcutaneous once daily) since his low independence level resulted in low mobility.

2 weeks after his admission, he received tenoxicam for 48 h to treat a left shoulder pain that had developed during resistance training. After 2 doses, he was completely asymptomatic.

5 days later, he developed right hip edema and postural hypotension. A blood count was performed and revealed a 4.1 g/dL decrease in his hemoglobin level. A hip computed tomography (CT) scan was obtained and revealed a massive hematoma on his right gluteus (Fig. 1).

After the surgical team’s evaluation, the patient underwent surgical exploitation and hematoma drainage. Due to local oozing, gauze pads were placed under the gluteus and removed during a second surgical intervention 72 h later. The patient was kept under ventral decubitus until complete recovery and was discharged in good condition. He was readmitted after 3 months for a rehabilitation program that was completed without any intercurrences.

Case 2

A 23-year-old male patient was admitted after having a traumatic spinal cord injury related to a motorcycle accident 4 months before. He had a complete lesion (AIS A) and a neurologic level at T6.

He reported having developed a sacral ulcer that had already healed. He reported no comorbidities and had used gabapentin for neuropathic pain, but with low adherence due to its costs because he had no health insurance. Although already in physical therapy and with normal upper limb strength, his level of independence was low. He was unable to transfer or dress himself without help. Prophylactic enoxaparin (40 mg subcutaneous once daily) was started upon admission.

On the third day of his admission, the patient presented with fever and tachycardia. There were no respiratory, abdominal, or urinary complaints. On physical examination, left hip edema and hyperemia were noted. A CT scan revealed a large hematoma extending from the left gluteus medius to the vastus lateralis (Fig. 2). He also had a 4 g/dL hemoglobin drop.

Subsequently, the patient went through surgical drainage. Areas of muscular necrosis were identified. Gauze pads were placed on the surgical site due to local oozing and removed during a second surgical procedure 3 days later. Closure was not performed due to local edema. The surgical wound was left open until 2 weeks later, when it was closed.

Fever developed 48 h later and a new local collection was identified. A fourth surgical procedure was performed in order to drain another hematoma. No other complications occurred, and after 2 weeks the patient was discharged. He was readmitted 6 months later for rehabilitation without any intercurrence.

A timeline for both cases that contains the laboratory values and AIS scores is provided in Table 1.

Discussion

Low-molecular-weight heparins are produced by the chemical or enzymatic depolymerization of unfractionated heparin in order to produce smaller chains of glycosaminoglycans with an average weight of 5000 Daltons. Low-molecular-weight heparins’ smaller size makes their affinity for activated factor X (Factor Xa) about 1000 times stronger than their affinity for thrombin [13]. They also produce a more predictable effect and are less associated with bleeding and severe events, such as heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, than unfractionated heparin [13, 14].

The safety and ease of use of low-molecular-weight heparins have led to their widespread use for both treatment and prophylactic purposes. Although safe, therapeutic doses of enoxaparin still have a risk of inducing severe bleeding in patients and there are reports of large hematomas in the gluteus, calves, and retroperitoneum, causing compartment syndrome in the lower limbs or abdomen, respectively [10,11,12]. To our knowledge, all these reports were related to the full anticoagulation dose of enoxaparin.

Enoxaparin sodium labeling information in the United States contains a warning about the risk of bleeding when it is co-administered with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [15]. In the first reported case, it’s possible that the co-administration of a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug may have facilitated the bleeding occurrence. In the second case, however, there were no other associated events that could have led to an increased bleeding risk. Both patients presented with severe bleeding [16] and had to undergo surgical drainage as surgical consultants were concerned about the risk of compartment syndrome.

Since both patients had insufficient transference skills, one possible mechanism for these adverse bleeding events is the repetitive trauma related to transfers from beds to wheelchairs and shear action while achieving correct positioning. Sensation deficits may have led to a delayed identification of the problem. According to the temporality, biological feasibility, and consistency with previous knowledge, it is highly likely that there was a causal relationship between the observed bleeding events and the prescribed pharmacological thromboprophylaxis.

International guidelines recommend that VTE prophylaxis should start as soon as possible after a spinal cord injury [6]. Previously, it was recommended that VTE prophylaxis should last up to 12 weeks, according to the Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine, depending on the type of lesion (whether complete or incomplete). This was substituted for a recommendation of a duration of at least 8 weeks, reinforcing the idea that there is an absence of good evidence on this subject [7, 8].

Currently, there aren’t any SCI-specific recommendations, to our knowledge, for indications of VTE prophylaxis on further admissions. Even though the risk of VTE decreases during the first 3 months after the spinal cord injury, it might still be almost twice as high as in the general population after 3 years and 20% higher after 8 years in out-patients [17, 18]. A systematic review of studies with varying VTE-prophylaxis strategies reports a DVT incidence of up to 8% in the sub-acute phase of the SCI [19]. There are few reports regarding the risk of VTE in individuals with chronic SCI admitted to rehabilitation and the most current guidelines contain no recommendations in favor or against pharmacological prophylaxis in this scenario, suggesting that these decision-making processes were based on clinical experience [20]. On the other hand, the reported risk of bleeding in individuals with SCI receiving pharmacological prophylaxis with LMWH has remained between 2.6% and 4.1% [21, 22].

Clinicians may currently use clinical prediction rules, such as the PADUA score or the GENEVA score, to decide whether or not to start prophylactic enoxaparin treatment [23, 24]. These scores are not validated for the spinal cord population. Immobility plays a major role in these algorithms, but it is possible that chronic spinal cord injury and muscle atrophy may lead to a collapse of venules, reducing the risk of thrombus formation. In higher lesions, spasticity may further reduce the risk of VTE and increase the risk of muscle rupture and bleeding [25].

One of the goals of contemporary medicine is avoiding unnecessary, harmful, duplicative, or non-evidence-based medical interventions [26]. It is possible that in sub-acute and chronic spinal cord injury, immobility may play a secondary role in VTE risk. The prescription of pharmacological prophylaxis may be an overtreatment related to an overestimation of the risk, but there is still no solid evidence to support thromboembolic disease prophylaxis neither in sub-acute nor in chronic spinal cord injury. Furthermore, we highlight that these patients frequently receive polypharmacy to control spasticity, pain (mainly neuropathic), depression, and bladder dysfunction [27]. The process of reducing polypharmacy may begin with a reduction in pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis.

Conclusion

The reported cases presented an uncommon complication of low-dose enoxaparin treatment and are, to our knowledge, the first reported cases of severe bleeding with prophylactic doses of enoxaparin. Although rare, the additional bleeding risk related to VTE prophylaxis may be unacceptable if the baseline risk for thromboembolic disease is below the threshold for pharmacologic prophylaxis.

Thromboembolism risk estimation and prophylaxis recommendations are part of the vast knowledge gap in the care of spinal cord injury patients. Current medical clinical rules may not apply to this specific population.

Risk estimation and the decision to initiate prophylaxis should be done on an individual basis and should not rely exclusively on plegia. The possible risks and expected benefits of such treatment should be discussed with patients. Further studies are needed to better assess risk in this specific group of patients.

References

Singh A, Tetreault L, Kalsi-Ryan S, Nouri A, Fehlings MG. Global prevalence and incidence of traumatic spinal cord injury. Clin Epidemiol. 2014;6:309–31.

Sekhon LH, Fehlings MG. Epidemiology, demographics, and pathophysiology of acute spinal cord injury. Spine. 2001;26(24 Suppl):S2–12.

Weingarden SI. Deep venous thrombosis in spinal cord injury. Overview of the problem. Chest. 1992;102(6 Suppl):636S–9.

Green D. Prophylaxis of thromboembolism in spinal cord-injured patients. Chest. 1992;102(6 Suppl):649S–51.

Casas ER, Sánchez MP, Arias CR, Masip JP. Prophylaxis of venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in patients with acute traumatic spinal cord lesions. Paraplegia. 1977;15:209–14.

Gould MK, Garcia DA, Wren SM, Karanicolas PJ, Arcelus JI, Heit JA, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonorthopedic surgical patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention ofthrombosis, 9th ed: american college of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e227S–77S.

Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine Prevention of thromboembolism in spinal cord injury. 2nd edn. Washington, DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America. 1999;1–20.

Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Prevention of venous thromboembolism in individuals with spinal cord injury: clinical practice guidelines for health care providers. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2016;22:209–40. https://doi.org/10.1310/sci2203-209. PMID: 29339863.

Spinal Cord Injury Thromboprophylaxis Investigators Prevention of venous thromboembolism in the rehabilitation phase after spinal cord injury: prophylaxis with low-dose heparin or enoxaparin. J Trauma. 2003;54:1111–5.

Limberg RM, Dougherty C, Mallon WK. Enoxaparin-induced bleeding resulting in compartment syndrome of the thigh: a case report. J Emerg Med. 2011;41:e1–4.

Malik A, Capling R, Bastani B. Enoxaparin-associated retroperitoneal bleeding in two patients with renal insufficiency. Pharmacother. 2005;25:769–72.

Yeung V, Formal C. Lower extremity hemorrhage in patients with spinal cord injury receiving enoxaparin therapy. J Spinal Cord Med. 2015;38:236–8.

Weitz JI. Low-molecular-weight heparins. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:688–98.

Büller HR, Gent M, Gallus AS, Ginsberg J, Prins MH, Baildon R, et al. Low-molecular-weight heparin in the treatment of patients with venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:657–62.

National Intitute of Health. Drug label information - enoxaparin sodium. 2009.

Schulman S, Angerås U, Bergqvist D, Eriksson B, Lassen MR, Fisher W, et al. Definition of major bleeding in clinical investigations of antihemostatic medicinal products in surgical patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:202–4.

Godat LN, Kobayashi L, Chang DC, Coimbra R. Can we ever stop worrying about venous thromboembolism after trauma? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:475–80.

Chung WS, Lin CL, Chang SN, Chung HA, Sung FC, Kao CH. Increased risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary thromboembolism in patients with spinal cord injury: a nationwide cohort prospective study. Thromb Res. 2014;133:579–84.

Alabed S, Belci M, Van Middendorp JJ, Al Halabi A, Meagher TM. Thromboembolism in the sub-acute phase of spinal cord injury: a systematic review of the literature. Asian. Spine J. 2016;10:972–81.

Mackiewicz-Milewska M, Jung S, Kroszczyński AC, Mackiewicz-Nartowicz H, Serafin Z, Cisowska-Adamiak M, et al. Deep venous thrombosis in patients with chronic spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2016;39:400–4.

Thumbikat P, Poonnoose PM, Balasubrahmaniam P, Ravichandran G, McClelland MR. A comparison of heparin/warfarin and enoxaparin thromboprophylaxis in spinal cord injury: the Sheffield experience. Spinal Cord. 2002;40:416–20.

Spinal Cord Injury Thromboprophylaxis Investigators prevention of venous thromboembolism in the acute treatment phase after spinal cord injury: a randomized, multicenter trial comparing low-dose heparin plus intermittent pneumatic compression with enoxaparin. J Trauma. 2003;54:1116–24.

Barbar S, Noventa F, Rossetto V, Ferrari A, Brandolin B, Perlati M, et al. A risk assessment model for the identification of hospitalized medical patients at risk for venous thromboembolism: the Padua Prediction Score. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:2450–7.

Nendaz M, Spirk D, Kucher N, Aujesky D, Hayoz D, Beer JH, et al. Multicentre validation of the Geneva Risk Score for hospitalised medical patients at risk of venous thromboembolism. Explicit ASsessment of Thromboembolic RIsk and Prophylaxis for Medical PATients in SwitzErland (ESTIMATE). Thromb Haemost. 2014;111:531–8.

Carpentier TJ, Kiekens C, Peers KH. Muscle rupture after minimal trauma of the spastic muscle: three case reports of patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:721–2.

Mason DJ. Choosing wisely: changing clinicians, patients, or policies? J Am Med Assoc. 2015;313:657–8.

Kitzman P, Cecil D, Kolpek JH. The risks of polypharmacy following spinal cord injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2014;40:147–53.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Almeida, R.L., Gonzaga, B.P.M., Beraldo, P.S.S. et al. Case report – Gluteal hematoma in two spinal cord patients on enoxaparin for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis: evidence needed for a wiser choice. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 5, 36 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-019-0180-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41394-019-0180-1

This article is cited by

-

Enoxaparin sodium/tenoxicam

Reactions Weekly (2020)