Abstract

Study design

Parallel-group, quasi-experimental study.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of a coping-oriented supportive programme (COSP) for people with spinal cord injury (SCI) over a 12-week follow-up.

Setting

SCI wards in two rehabilitation hospitals of Shaanxi, China.

Methods

Ninety-nine participants (mean age = 41, 88% males and 74% paraplegia) joined the COSP intervention (n = 50) or attention control (n = 49) group. The COSP intervention was focussed on the facilitation of coping skills and consisted of 8 weekly sessions, whereas the attentional control group was provided with 8 weekly didactic education sessions. Effects of the COSP intervention were determined by primary outcomes (coping and self-efficacy) and secondary outcomes (depression, anxiety, social support, life satisfaction and pain). Data were collected at pre- and post-intervention, as well as 4- and 12-week follow-up.

Results

Intention to treat analysis indicated statistically significant effects (with moderate to large effect sizes, all P-values < 0.01) on participants’ maladaptive coping, adaptive coping, self-efficacy, depression, anxiety, satisfaction of social support and life satisfaction immediately post-COSP. Statistically significant effects were found for maladaptive coping, self-efficacy, anxiety, depression, satisfaction of social support and life satisfaction at 4-week follow-up. Maladaptive coping, anxiety, satisfaction of social support and life satisfaction were also significantly improved at 12-week follow-up.

Conclusion

The COSP intervention resulted in medium-term psychosocial benefits for people with SCI and has potential for integration into routine inpatient rehabilitation practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

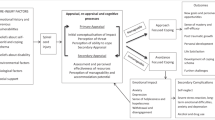

The incidence of spinal cord injury (SCI) lies between 10 and 83 per million people per year worldwide, and with 60,000 new cases a year, China has the highest prevalence of people with SCI in the world [1]. SCI causes serious physical disability and health problems, resulting in higher levels of psychological distress and lower levels of life satisfaction than the general population [2]. The stress and coping model has been considered as the most valid theory to explain the mechanism of psychological adjustment to the consequences of SCI [3]. People’s responses to the injury and its consequences begin with their cognitive process of appraisal, which includes an assessment of the situation in terms of impacts, threats, perceived ability to cope and available resources [4]. Individuals’ coping responses are based on the appraisals and feelings evoked [5]. Adaptive coping (e.g. positive reframing, problem-solving, engagement in physical rehabilitation and seeking social support) can result in positive emotions and optimal quality of life, whereas maladaptive coping (e.g. denial, dwelling on negative emotions, avoidance of social activities and abusing drugs or alcohol) can result in psychological distress, negative emotions and poor quality of life [6].

Helping people with SCI to be able to effectively cope with the initial challenges presented by the injury will improve their self-efficacy and subsequently encourage further coping attempts through positive reinforcement [3]. A higher level of self-efficacy could also facilitate the adoption of adaptive rather than maladaptive coping strategies when people are faced with stressful situations [3]. Coping and self-efficacy therefore constitute a dynamic process in promoting people’s psychosocial adaptation to life situations post-SCI.

The degree of psychosocial adaptation to SCI impacts upon a range of injury-related outcomes, for example it will influence an individual’s psychological well-being (i.e. levels of anxiety and depression), social support and relationships, as well as life satisfaction [7]. Coping resources, such as social support also have a role in buffering the psychological distress that is experienced during psychological adjustment to SCI [8]. Similarly, pain is a common co-morbidity following SCI (with a prevalence rate of around 75%) [9] and due to its bio-psychosocial nature this is also influenced by an individual’s cognitive responses [10]. Therefore, a holistic biopsychosocial model of SCI rehabilitation is appropriate to guide interventions because it emphasises the dynamic interactions between biomedical, psychological and social factors and highlights the equal importance of psychosocial support to biomedical rehabilitation [11]. Current research demonstrates the effectiveness of the biomedical and physiotherapy approaches commonly used in SCI inpatient rehabilitation [12].

However, the effectiveness of psychosocial care during the earlier stages of inpatient SCI rehabilitation has not been adequately established. Indeed, a systematic review of psychosocial interventions for people with SCI during inpatient rehabilitation identified key research gaps in this promising research area [13]. Most of the available studies of psychosocial interventions during SCI rehabilitation were conducted in Western countries and focused on people with high levels of depression and/or anxiety, and specific co-morbidities [13]. There is a paucity of intervention studies designed and implemented for Chinese people without clinically meaningful symptoms of anxiety or depression during their inpatient SCI rehabilitation [13, 14]. Such psychosocial care programmes may help to support people’s psychological adjustment to SCI and prevent potential deterioration of their mental health.

In order to address the research gaps existing in the current literature, we established a culturally sensitive psychosocial care intervention entitled ‘coping-oriented supportive programme (COSP)’ for Chinese people with SCI during inpatient rehabilitation [15]. The contents of the COSP intervention were informed by coping effectiveness training [16], Craig’s surviving and thriving with SCI [17] and a DVD-based psychoeducation programme [18]. The COSP intervention is rooted in cognitive and behaviour therapies and focuses on the facilitation of various coping strategies, in order to promote high levels of self-efficacy, positive emotions and life satisfaction for people with SCI. The COSP was designed to be used by rehabilitation nurses and address important specific Chinese cultural issues (such as face-saving, Confucianism and social norms) to be more sensitive and suitable for the Chinese population. A pilot evaluation of the COSP was conducted, and the findings supported the feasibility, acceptability and promising effects of the intervention [15].

The present study aimed to test the effectiveness of the COSP in improving people’s psychosocial outcomes following SCI. It was hypothesised that participation in the COSP would contribute to significantly greater improvements in participants’ coping ability and self-efficacy immediately after the intervention, and at 4- and 12-week follow-ups, when compared to those in the didactic education group. The effectiveness of the COSP intervention on improving secondary outcomes of anxiety, depression, social support, life satisfaction, and pain both immediately post intervention and at follow up was also of interest.

Methods

An open-label, quasi-experimental trial (ClinicalTrials.gov: registration NCT 02672670) with repeated measures (Time 1—baseline, Time 2—immediately after the intervention, Time 3–4-week follow-up and Time 4–12-week follow-up), two-group comparison design was adopted for this study. Ethical approval was obtained through the Human Subjects Research Ethics Sub-committee of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University and two study hospitals (HASEARS20151219002).

Recruitment and sampling

This study was conducted in two rehabilitation hospitals (under similar clinical standards and policies) from August 2016 to June 2017 in the city area of Xi’an, China. People who were medically stable and able to remain in their wheelchair (assessed by the physician in each SCI ward) for more than 2 h were eligible for further screening (by the researchers). Potential participants were eligible for inclusion if they: (1) planned to have inpatient rehabilitation for at least a 12-week period; (2) had a traumatic or non-traumatic SCI within 1 year or approximately 1 year; (3) were aged 18–64 years, and able to communicate in Mandarin; (4) had no brain injury; (5) did not have clinically meaningful symptoms of anxiety and depression (Chinese version of HADS subscale score of anxiety or depression < 9) [19]. Whereas, the exclusion criteria are those who were: (1) cognitively impaired (MMSE > 21), or currently had severe mental illness, or suffering from severe pain; (2) having frequent or serious somatic complaints (e.g. an extreme focus on pain, fatigue dizziness or other negative body experience); (3) complete social withdrawal or non-response to questions; (4) high risk of self-harm; (5) currently involved in other psychosocial interventions or clinical trials.

Sample size and sampling

A previous study using coping-based intervention for people with SCI indicated a large effect size (f > 0.40) for self-efficacy [20]. However the effects might be inflated due to the use of a historical control group. To be more prudent for the estimation of the sample size, a conventional medium effect size (f = 0.25) for behavioural or psychosocial interventions was used for the calculation [21]. Using a level of significance of 0.05, study power of 80% and taking into account a possible 20% drop-out rate [22], the sample size was calculated as 50 per group (i.e. totally 100 participants). Four SCI inpatient wards were selected for the study groups (one ward for the intervention group and another ward for the attentional control group in both hospitals). Then, proportionate sampling was utilised for the recruitment of individual participants. As the injury types and gender are two salient factors that influence intervention effects [23], the number of participants recruited from each ward was based on the ratio of the two injury types (3:1 for paraplegia vs. tetraplegia) and gender (7:1 for male vs. female). These ratios were determined by the historical records of patients’ admissions in the hospitals.

Interventions

Coping-oriented supportive programme

The COSP is a manualised psychosocial intervention programme for people with SCI undergoing inpatient rehabilitation. The programme consists of eight weekly, 1- to 1.5-h sessions, and included four phases (details in Table 1). Participants who joined five or more sessions were considered as successful completers. Details of the COSP intervention and Chinese culture considerations are presented in the Supplementary Material. The COSP intervention was delivered by a registered nurse with extensive training in both SCI wards.

Attentional control group

The control group was provided with brief educational group sessions (self-care information and personal skin care, bowel and bladder training) conducted by the rehabilitation nurses, which aimed to balance the social interaction and attention effects during group sessions between the COSP intervention and the attentional control group. It also consisted of eight 1- to 1.5-h sessions with professional contacts similar to the COSP group.

Outcome measurements

Primary outcomes

Participants’ coping strategies were assessed by the Brief-COPE Scale [24], consisting of 28 items and two conceptually distinct aspects of coping behaviours (i.e. maladaptive and adaptive coping). The Chinese version [25] indicates good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alphas > 0.75) for the two-factor solutions. Participants’ self-efficacy was assessed by the 16-item self-reporting Moorong Self-Efficacy Scale [26]. The Chinese version of the MSES demonstrates very good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93) [27].

Secondary outcomes

Participants’ symptom severity of anxiety and depression was assessed by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), and Cronbach’s alpha for the anxiety and depression subscales were found to be 0.81 and 0.74, respectively [28]. The Chinese version of HADS also indicates good internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.76 for anxiety and 0.78 for depression [29]. Pain intensity was measured with the Numerical Rating Scale, which has demonstrated good reliability with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.95 and good validity in the SCI population [30]. Social support was assessed with the Six-item Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ6) [31]. The Chinese version reported good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93) for the satisfaction of social support scale, and 0.90 for the number of social support scale [32]. Finally, life satisfaction was assessed by the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire-Short Form (Q-LES-Q-SF). The Chinese version [33] indicated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87) and content validity in the SCI population.

Data collection and analysis

All data were collected by two trained research assistants. Final data analysis was based on the intention to treat principle using IBM SPSS statistics 23.0. Last observation carried forward was used to manage missing data. Independent sample T-test (for continuous variables with normal distribution), Mann–Whitney U test (for ordinal variable) and Chi-square test (for categorical variables) were used for the between-group comparison to check the homogeneity of the study groups at baseline [34].

The effectiveness of the COSP was evaluated by comparing the changes over time in the outcome measures between the COSP and the control group over the 12-week follow-up. Without violation of the linearity of the dependent variable, multivariate normality and homogeneity of the variance–covariance, repeated measures mixed-model MANOVA test was finally adopted for most of the outcome variables (maladaptive coping, adaptive coping, self-efficacy, anxiety, depression and life satisfaction) to determine the interactional group*time intervention effects and the univariate between-group effects across time. A repeated measure of univariate ANOVA was performed for social support (i.e. amount of social support and satisfaction of social support), as these two variables were not correlated with other outcomes. Helmert’s contrasts tests were adopted to identify where the significant differences on each outcome were positioned if between-group effects were found significant. Mann–Whitney U test was used for ordinal variables.

Results

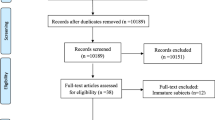

A total of 99 participants were recruited for the study. The study flow is presented in Fig. 1.

Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of participants at baseline

As seen in Table 2, the majority (88%) of the participants were male, with a mean age of 41, and over half were married. Two-thirds of the participants had completed tertiary education or vocational training. Half of them had an average household (monthly) income of 6001–9000 RMB (US$906–1358; US$1 = RMB6.6); and nearly 80% indicated that they received financial support for their medical care. Nearly all participants had a traumatic SCI, and 74% were paraplegic. Half of them had a complete SCI, and the average time since SCI was 7.8 months. There were no statistically significant differences in participants’ intervention attendance rates (χ2 = 0.21, P = 0.50) or completion rates (attended < 5 and ≥ 5 group sessions; χ2 = 0.25, P = 0.62) between the two groups. No adverse effects were observed during the study process.

Effectiveness of the COSP over the 12-week follow-up

Outcome measure scores at four-time points and results of intervention effects are presented in Table 3. Statistically significant group by time effects were noted, with COSP participants reporting improvements across primary outcomes (maladaptive coping, adaptive coping and self-efficacy) and secondary outcomes (depression, anxiety, life satisfaction and satisfaction of social support) in comparison to the attentional control group. Moderate to large effects were achieved for the outcomes mentioned above, with eta squared ranging from 0.09 to 0.36. However, there was no statistically significant group effect found on people’s amount of social support. For the pain level (measured by NRS), statistically significant differences were found at Time 3 (z = −2.25, P = 0.025) (the COSP group significantly lower than the control group) and Time 4 (z = −3.09, P = 0.002) (the COSP group significantly lower than the control group). The profile plots of the continuous outcome variables are presented in Fig. 2.

The Helmert contrasts test results (details in the Supplementary Material) indicated that there were statistically significant between-group differences across three post-tests (Times 2, 3 and 4) for maladaptive coping, anxiety, the satisfaction of social support and life satisfaction (all P-values < 0.05). However, there were statistically significant differences in adaptive coping and depression (P = 0.001) at Time 2 only. For participants’ self-efficacy, there were statistically significant differences found at Time 2 (P = 0.001) and Time 3 (P = 0.02).

Discussion

This is the first clinical trial to test the effectiveness of a Chinese culturally sensitive psychosocial care programme for people with SCI during their inpatient rehabilitation stage. The study findings are encouraging as the COSP participants demonstrated significant sustainable positive improvements in coping ability, self-efficacy, anxiety, depression, satisfaction of social support and life satisfaction when compared with the didactic education group participant over a 12-week follow-up period.

Positive effects of the COSP on participants’ coping abilities (both maladaptive coping and adaptive coping) were consistent with the findings of two previous studies that tested psychosocial interventions for people with SCI living in the community [35, 36]. Psychosocial interventions were also found to be effective in enhancing the coping ability of people with other kinds of acquired physical disabilities (i.e. stroke, limb amputation or multiple sclerosis) in an earlier study [37]. The interventions adopted within the current study and previous psychosocial care programmes share some characteristics that are intended to promote effective coping (e.g. problem-solving, challenging negative thoughts, relaxation, activity scheduling and assertiveness training). Therefore, the positive effects on the coping outcomes in our study seem to further confirm the usefulness/benefits of these individual techniques in people that are striving to adapt to the challenges of an acquired physical disability such as SCI.

It is noticeable that the COSP participants had great improvements in adaptive coping without a corresponding decrease of maladaptive coping scores. This may be because the study participants were recruited from rehabilitation wards and they have fewer opportunities to observe/notice and change their maladaptive coping behaviour (e.g. alcohol/drug abuse, smoking or avoidance to social interactions) in the relatively protective inpatient environment. Nevertheless, participants also reported improvements in maladaptive behaviour and significant increase of self-efficacy after attending the COSP intervention. Participants’ self-efficacy (measured by MSES) at baseline in the COSP is lower than those in Craig’s (2019) study [38]. This relatively low score may be because Chinese people with SCI could foresee great challenges and difficulties in their future community life as the infrastructure and community support systems (e.g. public transportation on accessibility, employment, community nursing, education and housing) are less developed in China compared with Western countries [39]. Theoretically, improved self-efficacy can be attributed to strong behavioural reinforcements through more frequent use of adaptive coping strategies and less use of maladaptive coping strategies [40]. Also, the COSP intervention covered content that particularly facilitated self-efficacy beliefs and highlighted the importance of self-efficacy. The resulting improvements in coping and self-efficacy would likely contribute to the subsequent improvements of the other psychosocial outcomes.

Participants’ depression improved significantly immediately after the COSP intervention, but there were no further marked improvements over the 4- and 12-week follow-up. As our target population are those without clinically meaningful symptoms of anxiety or depression, the mean scores of depression would not be expected to decrease much in the follow-up assessments. Nevertheless, there was no deterioration of the depression level compared with the baseline measurements. Future studies could consider adding some booster sessions during the follow-up stage to further strengthen the intervention effects. The positive effects on participants’ satisfaction of social support in our study are consistent with previous study findings [41]. Participants’ perceived social support in the COSP intervention would enrich their coping resources, and thus facilitate better coping and improve their self-efficacy in dealing with the consequences of SCI. The insignificant effects on participants’ number of supporters might be due to the protective inpatient rehabilitation environment, for example, because it is difficult for the participants to interact with outsiders and expand their social and support networks.

Theoretically, the improvements in the secondary study outcomes can be largely attributed to positive changes in participants’ coping ability and self-efficacy [42]. The improvements in perceived satisfaction of social support and mood may also have contributed towards enhanced life satisfaction [43]. The observed improvements in pain might be explained by the fact that chronic pain is a biopsychosocial condition that can be influenced by an individual’s appraisal and response [10]. Thus, levels of pain in the COSP participants’ may have reduced because they were encouraged to use more adaptive coping strategies (i.e. problem-solving) rather than denial or avoidance of the problem, as well as emotional coping to relieve pain-related distress [44, 45].

Strengths and limitations

The consideration of Chinese cultural issues when designing the COSP has contributed to the internal validity of the study and the strategies used for ensuring the intervention fidelity also strengthen the reliability of the findings. The primary methodological limitation of our study is the random allocation of SCI wards to the two study groups rather than the randomisation of individual participants. This was necessary due to a high risk of intervention contamination that would arise if both the treatment and control group participants were being treated on the same ward. Therefore, the study findings might be influenced by other unknown/uncontrolled confounding factors (e.g. patients’ personality traits, social environmental factors or specific clinical contexts) and conclusions generated from this trial need to be confirmed with a large-scale cluster randomised controlled trial. Also, the selective sample from two rehabilitation hospitals might not be representative of all the SCI population in mainland China. Finally, the self-reported subjective study outcome measures are subject to reporting bias, particularly because the participants could not be blinded to group allocation due to the nature of the psychosocial interventions.

Implications for clinical practice and future research

This study provides preliminary evidence supporting the effectiveness of the structured COSP intervention in improving the psychosocial outcomes of people with SCI. The findings may also suggest that rehabilitation nurses could be considered as appropriate health professionals in delivering psychosocial interventions with sufficient training and supervision from clinical psychologists. We recommend a multi-site randomised controlled trial design to be used for a future clinical trial of the COSP. Some objective outcomes (e.g. admission rates or observations of behaviour change) are also recommended for future studies. Long-term assessments (i.e. 1 or 2 years) for the COSP intervention effects would be ideal for future studies, as well as blinding of the study participants to specific study groups where possible.

Conclusions

This study pioneers the evaluation of a structured psychosocial care programme for Chinese people with SCI over a 12-week follow-up. The COSP intervention demonstrated significant improvements in participants’ coping ability and self-efficacy as well as other important psychosocial factors. Positive findings indicate the high potential for the integration of the COSP intervention into routine SCI rehabilitation.

Data availability

There is no data to deposit at this time. Reasonable requests for data will be considered.

Change history

09 October 2020

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

References

Qiu J. China spinal cord injury network: changes from within. Lancet Neurol 2009;8:606–7.

Post MWM, van Leeuwen CMC. Psychosocial issues in spinal cord injury: a review. Spinal Cord 2012;50:382–9.

Galvin LR, Godfrey HPD. The impact of coping on emotional adjustment to spinal cord injury (SCI): review of the literature and application of a stress appraisal and coping formulation. Spinal Cord 2001;39:615–27.

Kennedy P, Ebrary I. Psychological management of physical disabilities a practitioner’s guide. Hove, East Sussex, New York, NY: Routledge Taylor & Francis; 2007.

Folkman S, Lazarus RS, Gruen RJ, DeLongis A. Appraisal, coping, health status, and psychological symptoms. J Pers Soc Psychol 1986;50:571–9.

Kennedy P, Kilvert A, Hasson L. A 21-year longitudinal analysis of impact, coping, and appraisals following spinal cord injury. Rehabil Psychol 2016;61:92–101.

Barone SH, Waters K. Coping and adaptation in adults living with spinal cord injury. J Neurosci Nurs 2012;44:271–83.

Muller R, Peter C, Cieza A, Geyh S. The role of social support and social skills in people with spinal cord injury—a systematic review of the literature. Spinal Cord 2012;50:94–106.

Sezer N, Akkuş S, Uğurlu FG. Chronic complications of spinal cord injury. World J Orthop 2015;6:24–33.

Middleton J, Perry K, Craig A. A clinical perspective on the need for psychosocial care guidelines in spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Int J Phys Med Rehabil 2014;2:1–6.

Suls J, Rothman A. Evolution of the biopsychosocial model: prospects and challenges for health psychology. Health Psychol 2004;23:119–25.

Hicks A, Ginis KM, Pelletier C, Ditor D, Foulon B, Wolfe D. The effects of exercise training on physical capacity, strength, body composition and functional performance among adults with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Spinal Cord 2011;49:1103–27.

Li Y, Bressington D, Chien WT. Systematic review of psychosocial interventions for people with spinal cord injury during inpatient rehabilitation: implications for evidence‐based practice. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs 2017;14:499–506.

Peter C, Muller R, Cieza A, Geyh S. Psychological resources in spinal cord injury: a systematic literature review. Spinal Cord 2012;50:188–201.

Li Y, Bressington D, Chien W-T. Pilot evaluation of a coping-oriented supportive program for people with spinal cord injury during inpatient rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil 2019;41:182–90.

Kennedy P. Coping effectively with spinal cord injuries: a group program therapist guide. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2008.

Craig AR. Surviving and thriving with SCI: a tool box towards self-mastery. Ryde: NSW SCI Service; 2011.

Chen HY, Wu TJ, Lin CC. Improving self‐perception and self‐efficacy in patients with spinal cord injury: the efficacy of DVD‐based instructions. J Clin Nurs. 2015;24:1666–75.

Zheng LL, Wang YL, li HC. Aplication of hospital anxiety and depression scale in general hospital: n analysis in reliability and validity. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2003;15:29–34.

Kennedy P, Duff J, Evans M, Beedie A. Coping effectiveness training reduces depression and anxiety following traumatic spinal cord injuries. Br J Clin Psychol 2003;42:41–52.

Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing research: generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. 8th Edition, Philadelphia, USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

Guo Y, Logan HL, Glueck DH, Muller KE. Selecting a sample size for studies with repeated measures. BMC Med Res Method. 2013;13:100.

McMillen JC, Cook CL. The positive by-products of spinal cord injury and their correlates. Rehabil Psychol 2003;48:77–85.

Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’too long: consider the brief cope. Int J Behav Med 1997;4:92–100.

Wang CH, Tsay SL, Bond AE. Post‐traumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety and quality of life in patients with traffic‐related injuries. J Adv Nurs. 2005;52:22–30.

Middleton JW, Tate RL, Geraghty TJ. Self-efficacy and spinal cord injury: psychometric properties of a new scale. Rehabil Psychol 2003;48:281–8.

Chen HY, Lai CH, Wu TJ. A study of factors affecting moving‐forward behavior among people with spinal cord injury. Rehabil Nurs 2011;36:91–7.

Woolrich RA, Kennedy P, Tasiemski T. A preliminary psychometric evaluation of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in 963 people livingwith a spinal cord injury. Psychol Health Med 2006;11:80–90.

Zheng L, Wang Y, Li H. Application of hospital anxiety and depression scale in general hospital an analysis in reliability and validity. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry 2003;15:264–66.

Raichle KA, Osborne TL, Jensen MP, Cardenas D. The reliability and validity of pain interference measures in persons with spinal cord injury. J Pain 2006;7:179–86.

Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Shearin EN, Pierce GR. A brief measure of social support: practical and theoretical implications. J Soc Pers Relationships 1987;4:497–510.

Chang AM. Psychosocial nursing intervention to promote self-esteem and functional independence following stroke. PhD Dissertation, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong; 1999.

Lee Y-T, Liu S-I, Huang H-C, Sun F-J, Huang C-R, Yeung A. Validity and reliability of the Chinese version of the short form of Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Q-LES-Q-SF). Qual Life Res 2014;23:907–16.

Portney L, Watkins M. Foundations of clinical research: application to practice. Stanford, USA: Appleton & Lange; 2000.

Dorstyn D, Mathias J, Denson L, Robertson M. Effectiveness of telephone counseling in managing psychological outcomes after spinal cord injury: a preliminary study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2012;93:2100–8.

Perry KN, Nicholas MK, Middleton JW. Comparison of a pain management program with usual care in a pain management center for people with spinal cord injury-related chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2010;26:206–16.

Dorstyn D, Mathias J, Denson L. Psychosocial outcomes of telephone-based counseling for adults with an acquired physical disability: a meta-analysis. Rehabil Psychol 2011;56:1–14.

Craig A, Tran Y, Guest R, Middleton J. Trajectories of self-efficacy and depressed mood and their relationship in the first 12 months following spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2019;100:441–7.

Zhang C. ‘Nothing about us without us’: the emerging disability movement and advocacy in China. Disabil Soc. 2017;32:1096–101.

Marks R, Allegrante JP. A review and synthesis of research evidence for self-efficacy-enhancing interventions for reducing chronic disability: implications for health education practice (part II). Health Promot Pract 2005;6:148–56.

Li Y, Bressington D, Chien WT. Pilot evaluation of a coping-oriented supportive program for people with spinal cord injury during inpatient rehabilitation. Disabil Rehabil. 2019;41:182–90.

Kennedy P, Lude P, Elfstrom ML, Smithson E. Cognitive appraisals, coping and quality of life outcomes: a multi-centre study of spinal cord injury rehabilitation. Spinal Cord 2010;48:762–9.

Peter C, Müller R, Cieza A, Post MW, van Leeuwen CM, Werner CS, et al. Modeling life satisfaction in spinal cord injury: the role of psychological resources. Qual Life Res 2014;23:2693–705.

Heutink M, Post MW, Luthart P, Schuitemaker M, Slangen S, Sweers J, et al. Long-term outcomes of a multidisciplinary cognitive behavioural programme for coping with chronic neuropathic spinal cord injury pain. J Rehabil Med 2014;46:540–5.

Wollaars MM, Post MWM, van Asbeck FWA, Brand N. Spinal cord injury pain: the influence of psychologic factors and impact on quality of life. Clin J Pain. 2007;23:383–91.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the people with spinal cord injury for their participation in our study. The authors also appreciate the support of the health professionals in the two rehabilitation hospitals.

Funding

The study was supported by the Research Associate Money for Doctoral Candidate at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YL, DB and WTC contributed to the conception and design of the study, as well as analysis and interpretation of data. YL drafted the article with critical revision for important intellectual content from DB and WTC. All the authors approved the final version of the manuscript to be submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was obtained through the Human Subjects Research Ethics Sub-committee of the Hong Kong Polytechnic University and two study hospitals (HASEARS20151219002). The authors certify that all applicable institutional and governmental regulations concerning the ethical use of human volunteers were followed during the course of this research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Chien, W.T. & Bressington, D. Effects of a coping-oriented supportive programme for people with spinal cord injury during inpatient rehabilitation: a quasi-experimental study. Spinal Cord 58, 58–69 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-019-0320-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-019-0320-2