Abstract

Background

Non-Hispanic Black (NHB) men are at an increased risk for aggressive prostate cancer (PCa), making active surveillance (AS) potentially less optimal in this population. This concern has not been explored in other minority populations—specifically, Hispanic/Latino men. We recently found that Mexican-American men demonstrate an increased risk of PCa-specific mortality, and we hypothesized that they may also be at risk for an adverse outcome on AS.

Methods

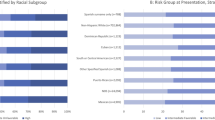

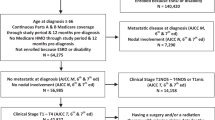

Using the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program, we extracted a population-based cohort of men diagnosed from 2004 to 2013 with localized or regional PCa, who had ≤2 cores of only Grade Group (GG) 1 cancer, and underwent radical prostatectomy (RP) with available biopsy and surgical pathology results. We measured discovery of high-risk PCa at RP and collected socioeconomic status (SES) data across different racial/ethnic groups. We defined aggressive tumors as either an upgrade to GG 3 or higher (GG3+) cancer or non-organ-confined disease (≥pT3a or N1). Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were developed to assess the association between racial/ethnic categories and the previously mentioned adverse oncologic outcomes both with and without adjusting for SES factors.

Results

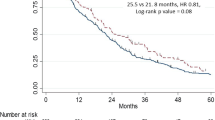

NHB and Mexican-American men were significantly more likely to have aggressive PCa, following RP. In multivariable logistic regression adjusting for SES factors and relative to non-Hispanic White (NHW) men, Mexican-American men had at increased odds of upgrading to GG3+ (OR 1.67; 95% CI [1.00–2.90]). NHB men were more likely to have non-organ-confined disease (OR 1.34; 95% CI [1.06–1.69]), while Mexican-American men had a similar risk to NHW men.

Conclusion

Among individuals with low-risk PCa and eligible for AS, Mexican-American and NHB men are at an increased risk of harboring more aggressive disease at RP. This novel finding among Mexican-Americans deserves further evaluation.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 4 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $64.75 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2016. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:7–30.

Oakley-Girvan I, Kolonel LN, Gallagher RP, Wu AH, Felberg A, Whittemore AS. Stage at diagnosis and survival in a multiethnic cohort of prostate cancer patients. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1753–9.

Iremashvili V, Soloway MS, Rosenberg DL, Manoharan M. Clinical and demographic characteristics associated with prostate cancer progression in patients on active surveillance. J Urol. 2012;187:1594–1600.

Sundi D, Ross AE, Humphreys EB, Han M, Partin AW, Carter HB, et al. African American men with very low-risk prostate cancer exhibit adverse oncologic outcomes after radical prostatectomy: should active surveillance still be an option for them? J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2991–7.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines), Washington, DC: NCCN; 2018.

Motel S, Patten E. Statistical portrait of Hispanics in the United States, 2011. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center; 2013.

Conomos MP, Laurie CA, Stilp AM, Gogarten SM, McHugh CP, Nelson SC, et al. Genetic diversity and association studies in US Hispanic/Latino populations: applications in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;98:165–84.

Browning SR, Grinde K, Plantinga A, Gogarten SM, Stilp AM, Kaplan RC, et al. Local ancestry inference in a large US-based Hispanic/Latino study: Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). G3 (Bethesda). 2016;6:1525–34.

Stern MC, Fejerman L, Das R, Setiawan WV, Cruz-Correa MR, Perez-Stable EJ, et al. Variability in cancer risk and outcomes within US Latinos by National Origin and Genetic Ancestry. Cancer Epidemiol Rep. 2016;3:181–90.

Motel S, Patten E. The 10 largest Hispanic origin groups: characteristics, rankings, top counties/Source: Pew Hispanic Center tabulations of the 2010 ACS. Hispanic trends. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center; 2012.

Young R. Race/ethnicity. AMA manual of style: a guide for authors and editors, 10th edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007.

Krieger N, Quesenberry C Jr, Peng T, Horn-Ross P, Stewart S, Brown S, et al. Social class, race/ethnicity, and incidence of breast, cervix, colon, lung, and prostate cancer among Asian, Black, Hispanic, and White residents of the San Francisco Bay Area, 1988–92 (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 1999;10:525–37.

Hoffman RM, Gilliland FD, Eley JW, Harlan LC, Stephenson RA, Stanford JL, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in advanced-stage prostate cancer: the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:388–95.

Shavers VL, Brown M, Klabunde CN, Potosky AL, Davis W, Moul J, et al. Race/ethnicity and the intensity of medical monitoring under ‘watchful waiting’for prostate cancer. Med Care. 2004;42:239–50.

Clegg LX, Li FP, Hankey BF, Chu K, Edwards BK. Cancer survival among US whites and minorities: a SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) Program population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1985–93.

Chinea FM, Patel VN, Kwon D, Lamichhane N, Lopez C, Punnen S, Kobetz EN, Abramowitz MC, Pollack A. Ethnic heterogeneity and prostate cancer mortality in Hispanic/Latino men: a population-based study. Oncotarget. 8.41 (2017): 69709.

National Institute of Cancer. Number of Persons by Race and Hispanic Ethnicity for SEER Participants. https://seer.cancer.gov/registries/data.html (accessed December 17, 2017).

Yu M, Tatalovich Z, Gibson JT, Cronin KA. Using a composite index of socioeconomic status to investigate health disparities while protecting the confidentiality of cancer registry data. Cancer Causes Control. 2014;25:81–92.

Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Soobader M-J, Subramanian SV, Carson R. Geocoding and monitoring of US socioeconomic inequalities in mortality and cancer incidence: does the choice of area-based measure and geographic level matter?: the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:471–82.

National Institute of Cancer. PSA Values and SEER Data. Updated April 14, 2017. https://seer.cancer.gov/data/psa-values.html (accessed December 17, 2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Katz, J.E., Chinea, F.M., Patel, V.N. et al. Disparities in Hispanic/Latino and non-Hispanic Black men with low-risk prostate cancer and eligible for active surveillance: a population-based study. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis 21, 533–538 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-018-0057-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41391-018-0057-6

This article is cited by

-

The association of patient and disease characteristics with the overtreatment of low-risk prostate cancer from 2010 to 2016

Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases (2024)

-

Disparities in germline testing among racial minorities with prostate cancer

Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases (2022)

-

Substantial Gleason reclassification in Black men with national comprehensive cancer network low-risk prostate cancer – A propensity score analysis

Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases (2022)

-

The impact of race/ethnicity on upstaging and/or upgrading rates among intermediate risk prostate cancer patients treated with radical prostatectomy

World Journal of Urology (2022)

-

Prostate cancer upgrading and adverse pathology in Hispanic men undergoing radical prostatectomy

World Journal of Urology (2022)