Abstract

Background

Although early nutrition is associated with neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years’ corrected age in children born very preterm, it is not clear if these associations are different in girls and boys.

Methods

Retrospective cohort study of infants born <30 weeks’ gestational age or <1500 g birth weight in Auckland, NZ. Macronutrient, energy and fluid volumes per kg per day were calculated from daily nutritional intakes and averaged over days 1–7 (week 1) and 1–28 (month 1). Primary outcome was survival without neurodevelopmental impairment at 2 years corrected age.

Results

More girls (215/478) survived without neurodevelopmental impairment at 2 years (82% vs. 72%, P = 0.02). Overall, survival without neurodevelopmental impairment was positively associated with more energy, fat, and enteral feeds in week 1, and more energy and enteral feeds in month 1 (P = 0.005–0.03), but all with sex interactions (P = 0.008–0.02). In girls but not boys, survival without neurodevelopmental impairment was positively associated with week 1 total intakes of fat (OR(95% CI) for highest vs. lowest intake quartile 62.6(6.6–1618.1), P < 0.001), energy (22.9(2.6–542.0), P = 0.03) and enteral feeds (1.9 × 109(9.5–not estimable), P < 0.001).

Conclusions

Higher early fat and enteral feed intakes are associated with improved outcome in girls, but not boys. Future research should determine sex-specific neonatal nutritional requirements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infants born very or extremely preterm (<32 weeks’ gestational age), or of very low birth weight (VLBW, <1500 g birth weight), are at high risk of faltering growth in the neonatal period.1 Supplying adequate nutrition to allow approximation of in utero growth trajectories is a recommended objective for neonatal practitioners,2 and undernutrition in the neonatal period, in preterm and VLBW infants is associated with adverse outcomes.3,4 However, the optimal amount, composition, and method of delivery of nutrition for preterm babies is not yet clear. Boys born preterm or VLBW are consistently reported to have worse outcomes than girls, including neonatal morbidity,5,6 mortality,7 and long-term neurodevelopment.5,8,9 Nutrition provided to the fetus may impact upon the risk of adverse long-term metabolic outcomes,10 and a number of studies, both human11 and animal,12 have shown intriguing differences in female and male responses to altered neonatal nutrition. It is therefore possible that sex-specific responses to early neonatal nutrition may explain some of the differences in outcome between girls and boys born preterm. The aim of this retrospective, observational cohort study was to determine whether relationships between neonatal nutritional intakes, neonatal growth and survival without neurodevelopmental impairment at 2 years of age are different in girls and boys born very preterm.

Methods

In 2007, the Newborn Intensive Care Unit (NICU) at National Women’s Health, Auckland, NZ introduced a new nutritional protocol. The aim of this protocol was to reduce early fluid intake, increase protein intakes and standardize parenteral nutrition prescribing practices for very preterm infants. A previously published audit of 80 surviving infants suggested that the new protocol was successful in achieving these aims, but was not associated with any differences in postnatal growth or 18-month neurodevelopmental outcomes.13 The change in nutritional protocol also affords the opportunity to examine the relationships between early nutrition and outcomes in a larger cohort of infants with wide variation in their nutritional intakes.

Ethics (NTY/09/98/EXP/AM02) and institutional (A + 4984) approvals were obtained for this study.

Participants

Infants born from 2005 to 2008 at <30 weeks’ gestation or <1500 g birth weight, and admitted to the NICU were identified from unit records. This included the 80 infants previously audited.13 Infants with significant congenital anomalies, those transferred into the unit later than 24 h after birth, and those transferred on or before the seventh postnatal day were excluded.

Neonatal data

All recorded enteral and parenteral fluid intakes (excluding blood products) from birth until the end of postnatal day 28 were collected from the medical records. Intakes from the calendar day of birth were excluded due to its variable duration. Parenteral, enteral and total macronutrient and energy intakes were calculated using reference data (Supplemental Table S1 (online)), and the current, highest recorded daily weight was used to calculate intakes per kg, which were then averaged over days 1–7 (week 1) and days 1−28 (month 1). The days on which 10 and 50% of total fluid intakes were via the enteral route were identified, as was the day 100% (full) enteral feeds were achieved.14 If full enteral feeds were not established by day 28, or the infant died before full feeds were reached, enteral feeding was reported as not established.

Antenatal steroid exposure, birth plurality, sex, maternal ethnicity,15 place of birth and the presence of prolonged rupture of the fetal membranes (>24 h) were collected from the neonatal record and CRIB-II score was calculated.16 Weight, head circumference and length measures at birth and at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age were converted to z-scores.17 Growth velocity was calculated using the exponential method.18

Neonatal outcomes

Neonatal morbidities included length of stay (from birth to discharge from a neonatal facility), intraventricular hemorrhage grade III or grade IV,19 retinopathy of prematurity stage 3 or 4,20 chronic lung disease (oxygen or mechanical ventilation at 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age), sepsis (a positive blood, urine or cerebrospinal fluid culture necessitating antibiotic treatment),21 and necrotizing enterocolitis Bell Stage ≥ 2.22 Deaths between birth and 2 years were recorded.

Neurodevelopmental outcomes at 2 years

Children underwent routine neurodevelopmental assessment at 2 years’ corrected age (±6 months) using the Bayley II, Bayley III or nonstandardized assessment. The primary outcome, survival without neurodevelopmental impairment, includes children who were alive and had no neurodevelopmental impairment on assessment at 2 years. Children with neurodevelopmental impairment were further categorized as having mild (motor score < −1 SD), moderate (cognitive score −1 to −2 SD, or mild-moderate cerebral palsy without cognitive impairment, or impaired vision requiring correction, or conductive hearing loss requiring aids) or severe impairment (cognitive score < −2 SD or severe cerebral palsy or bilateral blindness or sensorineural hearing loss requiring aids).23

Statistical analysis

Analysis was performed in JMP v11.2.0 (SAS Institute Inc.). Descriptive data are presented as number (%), mean (SD) or median (IQR) as appropriate. Between girls and boys, continuous data were compared using ANOVA, or Wilcoxon’s test for non-normal distributions. Categorical data were compared using chi-squared or Fisher’s Exact tests. The level of significance was taken as 0.05 throughout, with no correction for multiple comparisons. The associations between nutrition parameters, sex and the selected outcomes were explored using multiple logistic regression analysis. Gestational age and birth weight z-score were included in models a priori as confounders that may influence neonatal nutrition, growth, and outcome at 2 years. Analyses were additionally adjusted for neonatal morbidities found to be different between girls and boys (P < 0.05), and outcomes at 2 years were also adjusted for the type of assessment (Bayley II, Bayley III, other). Nutritional components found to have significant associations with both outcome and sex were further explored by estimating the odds ratios for the outcome for quantiles of nutritional intake separately in girls and boys.

Results

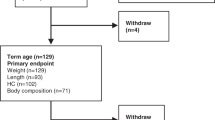

A total of 536 infants were admitted to the NICU July 2005–October 2008, of whom 478 (89%) were included in this study and 263 (55%) were boys (Fig. 1).

Girls and boys were similar in gestational age at birth, birth weight, birth weight z-score, CRIB-II score, ethnicity, antenatal steroid exposure and birth plurality (Table 1). Girls were less likely than boys to have necrotizing enterocolitis (3(1%) vs. 16(6%), P = 0.009) and sepsis (22(10%) vs. 46(17%), P = 0.02), but not other neonatal illnesses. Average protein, fat, carbohydrate and energy intakes were lower during week 1 than during month 1, and were similar in girls and boys (Table 1). Girls and boys achieved enteral feeds at similar ages, with breastmilk comprising the majority of enteral feedings for all infants (Table 1).

All infants lost weight in the first week after birth, reflected in an average growth velocity of −4.0 (−9.0–0.9) g kg−1 d−1 from birth to day 7 (Table 2). Growth velocity was similar in girls and boys from birth to day 7 and to day 28. Z-score change from birth to 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age could be calculated for weight in 374/478 (78%), head circumference in 332/478 (69%), and length in 312/478 (65%). The cohort as a whole did not achieve intrauterine-equivalent growth rates, with negative changes in z-scores for all growth parameters from birth to 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age (Table 2). In adjusted models, no nutritional component was associated with change in weight, head circumference or length z-scores from birth to 36 weeks’ postmenstrual age.

By 2 years of age, 38(8%) of the cohort had died, and 81(17%) did not have a neurodevelopmental assessment, so the composite outcome of survival without neurodevelopmental impairment could be determined in 180/215(84%) girls and 217/263(83%) boys (Table 2). Neurodevelopmental impairment occurred in 56/359(16%) children assessed at 2 years, was similar in girls and boys, and was moderate in the majority of cases. Girls were more likely than boys to achieve the composite outcome of survival without neurodevelopmental impairment (147(82%) vs. 156(72%), P = 0.02) (Table 2).

In unadjusted, multivariate logistic regression analysis, there was a positive association between the odds of survival without neurodevelopmental impairment and week 1 fat intake (OR(95%CI) 1.56(1.14–2.15), P = 0.005), but no associations with week 1 protein (1.51(0.83–2.75), P = 0.17) or carbohydrate (0.97(0.83–1.13), P = 0.71) intakes. Similar relationships were seen in girls where week 1 fat (5.36(2.59–12.60), P < 0.001) was associated with survival without neurodevelopmental impairment, but not protein (2.96(0.92–9.52), P = 0.06) or carbohydrate intake (0.82(0.62–1.09), P = 0.18). In contrast, there were no significant relationships between week 1 intakes of any of the three macronutrients and survival without neurodevelopmental impairment in boys (fat 1.00(0.70–1.44), P = 0.98, protein 1.17(0.57–2.42), P = 0.68, carbohydrate 1.05(0.86–1.27), P = 0.66).

In adjusted models, energy, fat, and enteral feed volumes in week 1, and energy and enteral feed volumes in month 1, were each associated with survival without neurodevelopmental impairment at 2 years and had significant sex interactions (Table 3). These relationships were similar when the outcome of neurodevelopmental impairment only was examined (Table 3). In girls, week 1 fat, energy and enteral fluid intakes were all positively associated with survival without neurodevelopmental impairment at 2 years, but there were no associations between these nutritional intakes and outcome in boys (Fig. 2). Similarly, month 1 enteral feed volumes were positively associated with survival without neurodevelopmental in girls but not boys (Fig. 2). Although energy intake in month 1 was associated with survival without neurodevelopmental impairment in both girls and boys, significantly increased odds of this outcome were seen for the highest quartile of energy intake in girls but only for the second quartile of energy intake in boys (Fig. 2).

Adjusted odds of survival without neurodevelopmental impairment at 2 years in girls (gray) and boys (black) in association with quartiles of nutrient intakes, where the reference values is the first quartile. Circles denote quartile 2, squares quartile 3 and triangles quartile 4. a Week 1 energy intake (reference value is energy intake <77 kcal kg−1 d−1) Girls Χ2 = 8.84, P = 0.03. Boys Χ2 = 4.00, P = 0.27. b Week 1 fat intake (ref. is fat intake <3.1 g kg−1 d−1). Girls Χ2 = 18.91, P < 0.001. Boys Χ2 = 4.20, P = 0.24. c Week 1 enteral feed volume (ref. is enteral feed volume <21 ml kg−1 d−1). Girls Χ2 = 15.96, P = 0.001. Boys Χ2 = 0.70, P = 0.87. d Month 1 energy intake (ref. is energy intake <120 kcal kg−1 d−1). Girls Χ2 = 12.82, P = 0.005. Boys Χ2 = 12.14, P = 0.007. e Month 1 enteral feed volumes (ref. is enteral feed volume <116 ml kg−1 d−1). Girls Χ2 = 10.99, P = 0.01. Boys Χ2 = 3.02, P = 0.39.

Discussion

Neonatal nutrition is an important modifier of short- and long-term outcomes of infants born preterm, but unlike for all other age groups,24 current recommendations for neonatal nutritional intakes do not differ by sex.25 In our cohort of infants born very preterm or at very low birth weight, we observed that associations between neonatal nutrition, growth and neurodevelopmental outcomes are different in girls and boys. These data support the hypothesis that preterm infants may have sex-specific nutritional requirements in the neonatal period.

Such an hypothesis is supported by evidence from animal,26 and human,27,28,29 studies that maternal breastmilk composition differs by offspring sex, providing higher concentrations of lipid and energy to boys. There is also evidence that supplementation of enteral feeds after preterm birth leads to sex-specific differences in growth and neurodevelopmental outcomes, with preterm boys who receive supplemented feeds showing bigger changes in short- and long-term growth,11,30 and improvements in verbal and overall IQ scores,31 compared to girls.

In our study, fat intake in the first postnatal week was strongly associated with survival without neurodevelopmental impairment in girls but not boys. The reason for the association between fat intake and outcome in girls, and the absence of this association in boys, is not clear, but could be due to differences in the requirements for, and metabolism of, fatty acids in early life. At 1 month of age, term-born girls have a higher percentage body fat and less fat-free mass than boys.32 Healthy infant girls have higher serum concentrations of triglycerides, cholesterol and low density lipoproteins than boys,33 and also different lipid compositions of the vernix (which is dissolved into the amniotic fluid by surfactant proteins then swallowed by the fetus34,35), with girls tending towards longer-chain hydrocarbon components.36 Further, a long-term study of docosahexaenoic acid supplementation to preterm neonates showed improved executive function only in girls,37 whereas fish oil supplementation to lactating mothers of term infants was associated with increased diastolic blood pressure and delayed puberty at 13 years only in boys.38 Together, these findings suggest sexual dimorphism in lipid requirement and metabolism, and hence potentially nutritional fat requirements in early life.

We observed an association between week 1 energy intake and survival without neurodevelopmental impairment in girls but not boys; findings similar to those recently reported in a cohort of 112 two-year olds born very preterm and exposed to high or low protein and energy intakes in the first 2 postnatal weeks.39 As this association mirrors the association between week 1 fat intake and outcome, it is difficult to distinguish whether energy or fat (which is the most energy-dense macronutrient) has the more important effect. We did not find any associations between week 1 or month 1 protein intakes and survival without neurodevelopmental impairment; an unexpected finding as increased early amino acid provision has previously been reported to improve survival without major disability in boys, but reduce cognitive scores in surviving girls.40

Enteral feed volumes in week 1 and month 1 were strongly associated with survival without neurodevelopmental impairment in girls but not boys. Achievement of enteral feeds may be delayed in infants who are small and sick, but given the similarities in gestational age, birth weight, and CRIB-II score between the sexes, delays in enteral feeding would be expected to affect girls and boys equally, and our data show that there were no differences between girls and boys for time to achieve 10%, 50% and full enteral feeds. Most of the enteral feed provided to infants in our cohort was maternal expressed breastmilk, and it is possible that sex-related differences in maternal breastmilk composition resulted in differential outcomes between preterm girls and boys.

Weight is the variable most commonly used to estimate adequacy of neonatal nutrition, yet the change in weight z-score between birth and 36 weeks was not associated with any component of nutritional intake in either sex. In term infants, weight is sensitive to relative lean mass, and weight may also change in response to hydration status. The use of weight as a marker for nutritional status also may be confounded through the presence of hypoalbuminaemia, resulting in edema in undernourished infants. Crown-heel length is difficult to measure accurately, especially in infants who are unable to tolerate significant handling. Thus, length measures in preterm infants may not accurately reflect body composition.41

It is possible that the interactions we have described between sex, fat and energy are secondary to our use of standard values to estimate enteral macronutrient intakes, and if actual, sex-specific breastmilk composition was known, these associations may no longer be observed. The volumes of enteral feed received by the cohort in the first week represent less than 50% of infants’ nutritional intakes, but enteral feeds provide the majority of nutrition in the first month; thus any disparities between estimated and actual enteral macronutrient intakes are likely to be most important during this time period. Our findings in this retrospective study may reflect reverse causation, and the associations described may merely reflect that infants with good outcomes grow better and feed better in the neonatal period, but this seems an unlikely explanation for our findings of sex-specific relationships with outcome. Further, although this is a relatively large cohort, the number of infants with poor outcome at 2 years is small. However, we prespecified an analysis plan specifically searching for sex-specific interactions and our findings are statistically robust.

Conclusions

Infants born very preterm have sex-specific associations between nutrition and outcomes. We found that higher early fat and enteral feed intakes were associated with improved outcome to 2 years in girls, but not boys. Prospective trials of neonatal nutrition should consider that outcomes may diverge by infant sex, and should therefore be adequately powered to report outcomes separately in girls and boys and examine sex interactions. Future recommendations for nutrition of preterm infants may need to be sex-specific.

Change history

26 May 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01582-8

References

Martin, C. R. et al. Nutritional practices and growth velocity in the first month of life in extremely premature infants. Pediatrics 124, 649–657 (2009).

Koletzko, B. et al. 1. Guidelines on paediatric parenteral nutrition of the European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) and the European Society for Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism (ESPEN), supported by the European Society of Paediatric Research (ESPR). J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 41(Suppl. 2), S1–S87 (2005).

Ehrenkranz, R. A. et al. Growth in the neonatal intensive care unit influences neurodevelopmental and growth outcomes of extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 117, 1253–1261 (2006).

Embleton, N., Pang, N. & Cooke, R. J. Postnatal malnutrition and growth retardation: an inevitable consequence of current recommendations in preterm infants? Pediatrics 107, 270–273 (2001).

Kent, A. L., Wright, I. M. & Abdel-Latif, M. E. New South Wales, Australian Capital Territory Neonatal Intensive Care Units Audit Group Mortality and adverse neurologic outcomes are greater in preterm male infants. Pediatric 129, 124–131 (2012).

Cuestas, E., Bas, J. & Pautasso, J. Sex differences in intraventricular hemorrhage rates among very low birth weight newborns. Gend. Med. 6, 376–382 (2009).

Stevenson, D. K. et al. Sex differences in outcomes of very low birthweight infants: the newborn male disadvantage. Arch. Dis. Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 83, F182–F185 (2000).

Hintz, S. R. et al. Gender differences in neurodevelopmental outcomes among extremely preterm, extremely-low-birthweight infants. Acta Paediatr. 95, 1239–1248 (2006).

Stålnacke, J. et al. A longitudinal model of executive function development from birth through adolescence in children born very or extremely preterm. Child Neuropsychol. 25, 318–335 (2019).

Barker, D. J. The fetal origins of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann. Intern. Med. 130(4 Pt 1), 322–324 (1999).

Lucas, A., Morley, R. & Cole, T. J. Randomised trial of early diet in preterm babies and later intelligence quotient. BMJ 317, 1481–1487 (1998).

Berry, M. J. et al. Neonatal milk supplementation in lambs has persistent effects on growth and metabolic function that differ by sex and gestational age. Br. J. Nutr. 116, 1912–25. (2016).

Cormack, B. E. et al. Does more protein in the first week of life change outcomes for very low birthweight babies? J. Paediatr. Child Health 47, 898–903 (2011).

Cormack, B. E. et al. Comparing apples with apples: it is time for standardized reporting of neonatal nutrition and growth studies. Pediatr. Res. 79, 810–820 (2016).

Ministry of Health. Ethnicity Data Protocols for the Health and Disability Sector (Ministry of Health, Wellington, NZ, 2004).

Parry, G., Tucker, J. & Tarnow-Mordi, W. CRIB II: an update of the clinical risk index for babies score. Lancet 361, 1789–1791 (2003).

Fenton, T. R. & Kim, J. H. A systematic review and meta-analysis to revise the Fenton growth chart for preterm infants. BMC Pediatr. 13, 1–13 (2013).

Patel, A. L. et al. Calculating postnatal growth velocity in very low birth weight (VLBW) premature infants. J. Perinatol. 29, 618–622 (2009).

Papile, L.-A. et al. Incidence and evolution of subependymal and intraventricular hemorrhage: a study of infants with birth weights less than 1,500 gm. J. Pediatr. 92, 529–534 (1978).

An international classification of retinopathy of prematurity. Prepared by an international committee. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 68, 690−697 (1984).

Chow, S. S. W. Report of the Australian and New Zealand Neonatal Network 2011 (ANZNN, Sydney, Australia, 2013).

Bell, M. J. et al. Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Therapeutic decisions based upon clinical staging. Ann. Surg. 187, 1–7 (1978).

National Women's Health. National Women's annual clinical report 2018 (National Women's Health, Auckland, NZ, 2018). https://nationalwomenshealth.adhb.govt.nz/healthprofessionals/annual-clinical-report/national-womens-annual-clinical-report/.

Capra, S. and members of the working party. Nutrient Reference Values for Australia and New Zealand: Including Recommended Dietary Intakes (National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), Canberra, Australia, 2006).

Agostoni, C. et al. Enteral nutrient supply for preterm infants: Commentary from the European Society of Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition Committee on Nutrition. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 50, 85–91 (2010).

Hinde, K. First-time macaque mothers bias milk composition in favor of sons. Curr. Biol. 17, R958–R959 (2007).

Thakkar, S. K. et al. Dynamics of human milk nutrient composition of women from Singapore with a special focus on lipids. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 25, 770–79. (2013).

Powe, C. E., Knott, C. D. & Conklin-Brittain, N. Infant sex predicts breast milk energy content. Am. J. Hum. Biol. 22, 50–54 (2010).

Fumeaux, C. J. F. et al. Longitudinal analysis of macronutrient composition in preterm and term human milk: a prospective cohort study. Nutrients 11. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11071525 (2019).

Fewtrell, M. S. et al. Randomized, double-blind trial of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation with fish oil and borage oil in preterm infants. J. Pediatr. 144, 471–479 (2004).

Lucas, A., Morley, R. & Cole, T. J. Randomised trial of early diet in preterm babies and later intelligence quotient. BMJ 317, 1481–1487 (1998).

Fields, D. A., Krishnan, S. & Wisniewski, A. B. Sex differences in body composition early in life. Gend. Med. 6, 369–375 (2009).

Dathan-Stumpf, A. et al. Pediatric reference data of serum lipids and prevalence of dyslipidemia: results from a population-based cohort in Germany. Clin. Biochem. 49, 740–749 (2016).

Narendran, V. et al. Interaction between pulmonary surfactant and vernix: a potential mechanism for induction of amniotic fluid turbidity. Pediatr. Res. 48, 120–124 (2000).

Nishijima, K. et al. Interactions among pulmonary surfactant, vernix caseosa, and intestinal enterocytes: intra-amniotic administration of fluorescently liposomes to pregnant rabbits. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 303, L208–L214 (2012).

Mikova, R. et al. Newborn boys and girls differ in the lipid composition of vernix caseosa. PLoS ONE 9, e99173 (2014).

Collins, C. T. et al. Neurodevelopmental outcomes at 7 years' corrected age in preterm infants who were fed high-dose docosahexaenoic acid to term equivalent: a follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 5, e007314 (2015).

Lauritzen, L. et al. Maternal fish oil supplementation during lactation is associated with reduced height at 13 years of age and higher blood pressure in boys only. Br. J. Nutr. 116, 2082–90. (2016).

Christmann, V. et al. The early postnatal nutritional intake of preterm infants affected neurodevelopmental outcomes differently in boys and girls at 24 months. Acta Paediatr. 106, 242–249 (2017).

van den Akker, C. H. et al. Observational outcome results following a randomized controlled trial of early amino acid administration in preterm infants. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 59, 714–719 (2014).

Kiger, J. R. et al. Preterm infant body composition cannot be accurately determined by weight and length. J. Neonatal Perinat. Med 9, 285–290 (2016).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by a Health Research Council of New Zealand Programme grant (12-095). A.C.T. was supported by a University of Auckland Senior Health Research Scholarship and a Gravida: National Centre for Growth and Development doctoral scholarship (12-01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design: J.E.H., F.H.B., A.C.T., J.M.A. Acquisition of data: J.M.A., A.C.T., J.T. Analysis and interpretation: J.E.H., A.C.T., B.E.C. Drafting the article: A.C.T., J.E.H., J.M.A. All authors critically revised and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tottman, A.C., Bloomfield, F.H., Cormack, B.E. et al. Sex-specific relationships between early nutrition and neurodevelopment in preterm infants. Pediatr Res 87, 872–878 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-019-0695-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-019-0695-y

This article is cited by

-

Identification and prediction model of placenta-brain axis genes associated with neurodevelopmental delay in moderate and late preterm children

BMC Medicine (2023)

-

Sex differences in preterm nutrition and growth: the evidence from human milk associated studies

Journal of Perinatology (2022)

-

Early visuospatial attention and processing and related neurodevelopmental outcome at 2 years in children born very preterm

Pediatric Research (2021)

-

Do preterm girls need different nutrition to preterm boys? Sex-specific nutrition for the preterm infant

Pediatric Research (2021)