Abstract

Background

The objective of this study was to characterize structural changes in the healthy in vivo placenta by applying morphometric and textural analysis using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and to explore features that may be able to distinguish placental insufficiency in fetal growth restriction (FGR).

Methods

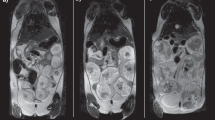

Women with healthy pregnancies or pregnancies complicated by FGR underwent MRI between 20 and 40 weeks gestation. Measures of placental morphometry (volume, elongation, depth) and digital texture (voxel-wise geometric and signal-intensity analysis) were calculated from T2W MR images.

Results

We studied 66 pregnant women (32 healthy controls, 34 FGR); during the study period, placentas undergo significant increases in size; signal intensity remains relatively constant, however there is increasing variation in spatial arrangements, suggestive of progressive microstructural heterogeneity. In FGR, placental size is smaller, with great homogeneity of signal intensity and spatial arrangements.

Conclusion

We report quantitative textural and morphometric changes in the in vivo placenta in healthy controls over the second half of pregnancy. These MRI features demonstrate important differences in placental development in the setting of placental insufficiency that relate to onset and severity of FGR, as well as neonatal outcome

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Placental dysfunction is a leading cause of adverse outcomes throughout the lifespan, including still birth and perinatal mortality.1,2 For survivors, acute and chronic placental dysfunction is responsible for lifelong morbidity, with increased risk of growth failure, premature birth and brain injury in the immediate peri-partum period, as well as cardiovascular, metabolic, and neuropsychiatric morbidity throughout childhood and into young adulthood.2,3,4 Despite the critical functions of sustaining normal fetal development, there is a paucity of tools to assess in vivo placental health prior to the onset of fetal compromise. Indeed, placental insufficiency is most often identified only after the development of fetal growth restriction (FGR), or fetal compromise. Ex vivo evaluation of the placenta reveals chronic inflammatory changes and vascular injury in FGR,5,6 yet there are no clinically available tools to identify microarchitectural changes in the in vivo placenta.

Textural analysis can quantify local and global differences in digital images on a voxel-by-voxel level that may be indiscernible to the human eye, thus allowing for objective, detailed image analysis.7 In medical imaging, textural analysis of structural magnetic resonance images (MRI) has been applied to identify pathological tissues in tumor analysis, Alzheimer’s disease, and seizure disorders.7,8,9 In pregnancy, gestational age (GA) estimation has also been performed through textural analysis of placental ultrasound images.10 The aim of this study was to explore the application of advanced textural and morphometric analysis of MR images of the in vivo placenta in both healthy and high-risk pregnancies, namely those complicated by FGR in order to assess in vivo microstructural development that remains indiscernible with conventional imaging. We hypothesized that textural and morphometric analysis would detect significant differences between healthy and growth-restricted placental microstructure.

Methods

Subjects

We recruited pregnant women with singleton pregnancies of 18 weeks gestation or later as part of a prospective observational study at Children’s National Health Systems (CNHS). Healthy controls had no significant past medical history, without chronic or pregnancy induced illnesses, and normal screening serum and anatomic studies during the pregnancy and were enrolled in a concurrent fetal imaging study. A pregnancy was considered complicated by placental-based FGR if the sonographically estimated fetal weight was < 10th centile using Hadlock equation for weight11 and either (a) the umbilical artery pulsatility index was > 95th centile for gestational age and/or cerebroplacental Doppler ratio < 112,13 or (b) evidence of asymmetric growth demonstrated by a lagging abdominal circumference (measuring at least 2 weeks smaller than expected for GA).14 Any maternal co-morbidities within FGR were noted. Subjects with FGR were identified by the primary obstetrician and maternal-fetal specialist at any point during the latter half of gestation, and were enrolled for imaging within one week of diagnosis. Pregnancies with FGR secondary to congenital anomalies or infections were excluded. Additional exclusion criteria included any maternal contraindications to MRI for either group. The study has been approved by the hospital’s Institutional Review Board and written, informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Imaging: MRI acquisition

All women underwent the exact same MRI imaging protocol on a 1.5 T Discovery MR450 scanner (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin) using an 8-channel surface receiver coil (USAI, Aurora, OH). Dedicated single shot fast spin echo (SSFSE) fat suppressed T2-weighted images in the maternal axial or coronal plane were acquired for full placental coverage. Acquisition parameters were: TE = 160 ms, TR = 1100 ms, 4 mm slice thickness, and 40 to 60 consecutive slices for full placental coverage. All images were reviewed by a single attending pediatric radiologist to screen for gross structural abnormalities of the placenta or fetus (D.B.).

Imaging: post-processing

Manual segmentations were created for each placenta using ITK-SNAP software15 by one of two scientists with expertize in advanced MRI and subsequently evaluated using the Dice similarity coefficient metric.16 Using an in-house pipeline, coarse 3D meshes of each placental segmentation were generated using CGAL followed by a Poisson surface reconstruction to create the final 3D surface (Supplementary Figure 1).17,18 From this 3D surface, we extracted three morphometric features, including volume, thickness, and elongation.19 From the original segmentation, three sets of increasingly complex textural features characterizing gray-level appearance (Supplementary Table 1) for a total of 22 features were computed.

Imaging: feature selection

To measure in vivo changes of placental development throughout gestation, we studied the evolution of all 22 features as a function of GA and gender within our healthy control cohort. All 22 features were then applied to compare healthy controls and FGR; features were classified into three categories to aid with interpretation: (a) shape (b) symmetry or homogeneity, and (c) coarseness. Shape features referred to gross, macrostructural elements, including volume, thickness, and elongation. For the voxel-based analysis in the second and third categories, each gray-scale image was first normalized to develop the mean gray value. The voxel-based analysis for the second category utilized the gray-scale histogram to describe the distribution of gray-scale values using the related measures of symmetry, uniformity, and homogeneity. The third category adds an additional dimension of spatial analysis, quantifying the number of sequential voxels with similar gray-scale metrics. Long runs describe regions with a greater number of sequential voxels with similar properties, and short runs reflect smaller numbers of similar, sequential voxels. High values of long runs, or a large region of similar characteristics, represent a coarser texture; conversely, high values of short runs, represent a finer, or smoother, texture. These features can be further characterized by adding additional descriptors, such as gray-level values, to result in the final feature description, such as “short-run low-gray-level emphasis” or “short-run high gray-level emphasis.”

Sonography

All pregnancies complicated by FGR underwent complete fetal sonographic assessment of both anatomy and Doppler evaluation as part of the study protocol on the same day as the MRI study using a LOGIQ E9 ultrasound scanner (GE Healthcare, WI). Abdominal circumference, head circumference, femur length, and estimated fetal weight were measured and plotted according to GA.11 Fetal middle cerebral (MCA) and umbilical arterial (UA) flow velocities were measured using a pulse-wave Doppler, and pulsatility indices (PI) were calculated. The cerebroplacental ratio (CPR) was calculated by dividing the middle cerebral artery pulsatility index by the umbilical artery pulsatility index.20 Subjects were classified into the sub-group of abnormal Doppler studies if the UA PI was > 95 centile for gestational age and/or the CPR was less than 1.21 All sonographic studies were reviewed by a single attending radiologist (D.B.).

Healthy control pregnancies underwent complete fetal echocardiographic assessment using a Vivid 7 ultrasound scanner (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI) as part of an adjunct prospective study. Fetal middle cerebral and umbilical arterial flow velocities were measured using a pulse-wave Doppler; pulsatility indices, CPR, and z-scores (derived from normal references) were calculated.21

Clinical data

Clinical and demographic data were extracted from the maternal and neonatal charts, including race, ethnicity, maternal co-morbidities, fetal gender, and gestational age at study. Neonatal outcomes included gestational age and birth weight at delivery. Each MRI was reviewed by a pediatric radiologist to evaluate for placental malformations and fetal anomalies.

Biostatistics

We performed intra- and inter-rater reliability analysis for the manual placental segmentations. Generalized linear mixed models, which account for the correlation between multiple measures on the same patient, with identity or log-link functions, as appropriate, to account for minor deviations from normal were used to evaluate changes in textural features across GA among controls, as well as differences in textural features between control and FGR groups. This methodology allows for the original scale of the outcome to be retained, without the interpretation bias that may occur when transforming variables.22 Results were similar using log-transformed outcome variables in linear mixed models, though back-transformed mean estimates varied slightly. Associations with neonatal outcomes were also investigated. GA at the time of the scan was controlled for in all group analyses. SAS software was used for all analyses; a p-value of < 0.05 was considered significant.23 Given the exploratory nature of this study, there were no adjustments made for multiple comparisons, in an effort to identify all potentially relevant associations.24

Results

Subjects

We studied a total of 66 pregnant women and acquired 94 fetal MRI scans: 32 pregnant volunteers with healthy fetuses (20 of which had 2 fetal MRI studies), and 34 pregnant women diagnosed with FGR (8 of which had 2 fetal MRI studies). Additional clinical and demographic data are presented in Table 1. Of note, all healthy controls delivered term, appropriate for gestational age infants and none of the subjects, healthy or FGR, had gross placental lesions noted on clinical evaluation of the T2W images.

Imaging: MR and post-processing quality and evaluation

No data were discarded due to poor image quality or artifact. Dice indices for intra- and inter-rater reproducibility for placental segmentations were 0.83 and 0.87, respectively.

Textural and morphometric features as a function of gestational age in healthy controls

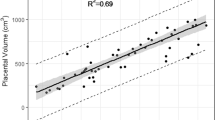

Placental volume, thickness, and elongation increased with advancing GA, (p < 0.005; Fig. 1). Five additional textural features were positively associated with gestational age: gray-level non-uniformity (p = 0.03), low-gray-level emphasis (p = 0.01), and short-run low-gray-level emphasis (p = 0.002) increased with advancing GA; there was a corresponding decrease in high gray-level emphasis (p = 0.02) and short-run high gray-level emphasis (p = 0.02) with advancing GA. These features reflect an overall increase in variation of gray-level values (increasing low-gray levels) with smaller regional clusters of similar voxels, suggesting increased tissue heterogeneity with advancing GA in healthy controls.

Impact of gender on textural and morphometric features in healthy controls

In evaluating signal-intensity features, we found that male fetuses demonstrated higher energy and inverse different movement levels compared to females (p = 0.02 and p = 0.03, retrospectively), as well as lower entropy levels (p = 0.04), reflecting greater orderliness and regularity of signal intensity in males (Supplementary Table 1). There was no gender difference in morphometric features or higher-order textural features (Table 2). Additional adjustment for gender in FGR analyses did not alter model estimates.

Group differences in textural and morphometric features between healthy controls and FGR

Of all the features analyzed, 13 were significantly different between healthy controls and FGR (Table 3 and Supplementary Table 2). These features were then categorized into differences in morphometry (volume, thickness, and elongation), symmetry & homogeneity of signal intensity (normalized mean gray-level, kurtosis, skewness, cluster shade, and cluster prominence), and coarseness or voxel-wise variation in spatial arrangements of the different signal intensities (short-run emphasis, SRE; gray-level non-uniformity, GLNU; run length non-uniformity, RLNU; short-run low-gray-level emphasis, SRLG; and long-run high gray-level emphasis, LRHG).25

Morphometric features revealed smaller placentas in FGR, with decreased volume (p = 0.0004), thickness (p = 0.03), and elongation (p = 0.03) in FGR compared to controls. After normalization of the gray levels, mean gray values were greater in FGR compared to controls (p = 0.01). Decreased kurtosis, skewness, cluster shade, and cluster prominence in FGR suggests greater symmetry and signal homogeneity (p = 0.05, p = 0.005, p = 0.009, and p = 0.009, respectively). The run-length metrics, including SRE, GLNU, RLNU, SRLG, and LRHG quantify the relationship of each voxel with surrounding voxels. The higher value of SRE in FGR suggests a finer texture in FGR (p < 0.001) with greater variation in gray levels (GLNU) and run length (RLNU) compared to controls (p = 0.02 and p = 0.005, respectively). Specifically, in FGR, the placentas demonstrate higher short runs of low-gray values, and fewer long runs of high gray values compared to controls (SRLG and LRHG; p = 0.02 and p = 0.0001, respectively). Collectively, these features demonstrate smaller placentas in FGR with greater homogeneity of signal intensity, yet higher variability in spatial arrangements compared to controls.

Textural and morphometric features in relation to Doppler sonography

A sub-group analysis of significant features between healthy controls and FGR pregnancies with and without Doppler abnormalities revealed a varying profile of affected features (Table 4). FGR pregnancies with Doppler abnormalities had decreased volume, elongation, kurtosis, and skewness compared to controls. Similarly FGR pregnancies without Doppler abnormalities also had decreased volume, kurtosis, and skewness, but also demonstrated differences in signal symmetry, namely cluster shade and cluster prominence. Furthermore, FGR pregnancies without Doppler abnormalities had greater SRE (smoother texture) compared to controls, but FGR pregnancies with Doppler findings did not. Conversely, SRLG and LRHG were most affected in FGR pregnancies with abnormal Dopplers.

Textural and morphometric features in relation to onset of diagnosis

We also explored the timing of FGR with the morphometric and textural features described above. For the pregnancy diagnosed with FGR in the second trimester, all three morphometric measures differed significantly from controls, whereas for the late, third trimester diagnosis, only volume was significantly reduced compared to controls. In Table 5, we summarize these differences, and as with the sub-group analysis in relation to Doppler anomalies, this sub-group analysis of diagnosis onset, reflects a variable profile of affected features.

Textural and morphometric features and neonatal outcome

Of the 13 features that differed between FGR and controls, 10 features were associated with absolute birth weight, and 9 with birth weight z-scores to account for differences in gestational age (Table 6). Interestingly 2 separate features, cluster shade and cluster prominence (p = 0.05 and p = 0.05) were positively associated with gestational age at birth for all infants.

Discussion

In this study, we report for the first time both morphometric and textural changes of the in vivo placenta during the second half of gestation as detected by MRI and examine the discriminating abilities of these features in pregnancies complicated by FGR. In healthy pregnancies, gross measures of placental size, including volume, thickness and elongation, increase with advancing GA, while textural features of signal intensity suggest that these metrics do not change over time. We also demonstrate a modest but significant increase in textural smoothness, namely greater non-uniformity and “short runs” with advancing gestational age in healthy controls. We interpret these metrics to reflect increasing complexity of microstructural arrangements, while maintaining the overall signal intensity relatively constant.

We further show that both textural and morphometric features of the in vivo placenta vary in FGR compared to controls; in addition to the expected reduction placental size, the absolute values of textural metrics are greater in FGR when accounting for gestational age, suggesting premature placental aging in FGR. Interestingly, while morphometric and textural features can discriminate placental differences between FGR cases with and without Doppler abnormalities, the pattern of affected features differs between these sub-groups. In particular, placental insufficiency with abnormal Doppler findings have significant differences in the signal-intensity metrics, perhaps related to differences of water content within the placenta, while FGR with normal Doppler studies have greater abnormalities in the run-length metrics, perhaps related to differences in tissue microstructural development.

Lastly, this study also explored the impact of gender on placental morphometric and textural features. We only identified three features that differed between healthy male and female fetuses: all reflecting textural differences in signal-intensity measures, namely energy, entropy, and inverse different movement. These differences reflect greater homogeneity of gray-scale values and more symmetry of the gray-scale histogram in male placentas compared to females but were unable to detect any gender-related differences in FGR.

Placental development: insights from gross and histopathology

Aberrations in gross placental growth, as detected by decreased weight on pathology evaluation or the morphometric measures described in this study, likely reflect a decreased number of functional placental units needed to support fetal growth.26,27 Interestingly, when FGR is diagnosed in the second trimester, volume, elongation, and thickness are significantly reduced compare to controls, whereas the late-onset of FGR only affects volume. We posit that with early-onset FGR there is a more significant reduction in the developing placental units that is detected by gross measures of size and shape. By the third trimester, the overall shape of the placenta seems to have been well defined so that primarily volume is affected in late-onset FGR.

Histopathology of the placenta in FGR also demonstrates varying anomalies including inflammatory, thrombotic, and morphologic changes, as well as a generally underdeveloped vascular tree.5,28,29,30 These in turn may result in differences in water content, and thus signal intensity, as well as microstructural development, and thus spatial arrangements of the various gray-scale signals.

Given that the pattern of histopathologic changes in placental insufficiency varies with the sub-group of FGR studied,5 it perhaps is not surprising that we also detect a variable pattern of textural features affected in individual FGR sub-groups. Similarly, while nearly all morphometric and textural features were associated with birth weight, only two measures of symmetry (cluster shade and cluster prominence) were associated with GA at birth. These differences suggest that this method may better identify the diverse pathologic states that lead to the umbrella diagnosis of FGR. Further study to validate these measures with ex vivo findings and neonatal outcomes is warranted.

Placental development: insights from in vivo imaging

Three-dimensional sonography has been used to describe in vivo placental development,31 however these volumetric techniques have not been sufficient to predict SGA infants.32,33 Additional morphological analyses, such as 2D sonographic measures of placental diameter and placental thickness are more promising metrics in the prediction of SGA, particularly in the first half of pregnancy.34,35,36 In MRI, variations in gray-scale signal intensity measured by textural analysis may reflect microstructural changes that are invisible to the human eye. Indeed, textural analysis in biomedical imaging has been shown to more reliably identify and distinguish pathologic tissue from healthy tissue in various disease states, including ones marked by microstructural and inflammatory changes.37,38,39,40,41 Using similar techniques, we show that several textural and morphometric features of the placenta vary in FGR compared to controls and suggest that this technique may allow for the in vivo detection of placental maldevelopment, particularly microstructural and chronic inflammatory changes. For example, the run-length metrics, measures of textural coarseness, reveal that there is an increase in textural smoothness with advancing gestation in healthy pregnancies; however, textural smoothness is even greater in FGR compared to controls, even when accounting for GA. Whether these differences reflect advanced placental maturation that have been associated with FGR,42 or more complex vascular and microstructural changes that can occur with placental disease, remains unknown.

Strengths and limitations

We have shown that textural and morphometric analyses of MR images can provide direct interrogation of placental development and detect alterations in the FGR cohort that otherwise were undetected by conventional MR evaluation. We postulate that abnormalities in placenta size, coupled with differences in signal intensity and spatial-variability of gray-scale signals, represent differences in gross and microstructural placental development. If confirmed in subsequent studies, these metrics may allow for the in vivo detection of distinct pathologies of placental dysfunction that converge to result in compromised fetal growth.

Although this work has a number of strengths, the limitations deserve mention. First, manual segmentation of placental images is a time-intensive endeavor, and future studies for the automation of this step are needed. Nonetheless, we were able to demonstrate strong inter- and intra-rater reliability between scientists. In addition, we acquired images utilizing 4 mm slice thickness, which may have masked some of the finer microstructural differences below this level of resolution. Furthermore, FGR can result from maternal, fetal, or placental mechanisms; while the inclusion criteria were designed to identify placental-based FGR, the population studied was as heterogeneous as the known pathology that results in placental dysfunction. Given the hypothesis-generating nature of this study, we performed a significant number of assessments without adjusting for multiple comparisons, in order to identify all potentially relevant features. While this approach has identified several in vivo textural features that may distinguish pathologic placental development, larger, prospective studies are needed to validate these findings. Future studies are warranted to determine if textural changes in the placenta can be detected prior to the onset of FGR, and if these features correlate with ex vivo histopathology. Technical advances in deep machine learning may reliably identify the most relevant individual and amalgamated features, that in future will allow for the most optimal assessment of healthy placental development. The potential application of these analyses in future, however, must be balanced by the significant cost associated with MRI, as well as the required expertize for the safe evaluation and interpretation.

Conclusions

This study is the first to describe MRI-based textural changes of the in vivo placenta in healthy and high-risk fetuses during the second half of pregnancy. We demonstrate that a number of distinguishing textural features consistent with increased placental symmetry and smoothness are present in placental-based FGR, both with and without Doppler changes, and for both early- and late-onset FGR. By developing novel tools such as those described here, we can better interrogate in vivo placental health, in order to optimize fetal care and the perinatal transition.

References

Kim, C. J., Romero, R., Chaemsaithong, P. & Kim, J. S. Chronic inflammation of the placenta: definition, classification, pathogenesis, and clinical significance. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 213(4 Suppl), S53–S69 (2015).

Gagnon, R. Placental insufficiency and its consequences. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 110(Suppl 1), S99–S107 (2003).

Morgan, T. K. Role of the placenta in preterm birth: a review. Am. J. Perinatol. 33, 258–266 (2016).

Wu, Y. W. & Colford, J. M. Jr. Chorioamnionitis as a risk factor for cerebral palsy: a meta-analysis. JAMA 284, 1417–1424 (2000).

Mifsud, W. & Sebire, N. J. Placental pathology in early-onset and late-onset fetal growth restriction. Fetal Diagn. Ther. 36, 117–128 (2014).

Perrone, S., Tataranno, M. L., Negro, S., Longini, M., Toti, M. S. & Alagna, M. G. et al. Placental histological examination and the relationship with oxidative stress in preterm infants. Placenta 46, 72–78 (2016).

Di Cataldo, S. & Ficarra, E. Mining textural knowledge in biological images: applications, methods and trends. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 15, 56–67 (2017).

Sorensen, L., Igel, C., Liv Hansen, N., Osler, M., Lauritzen, M. & Rostrup, E. et al. Early detection of Alzheimer’s disease using MRI hippocampal texture. Hum. Brain Mapp. 37, 1148–1161 (2016).

Suoranta, S., Holli-Helenius, K., Koskenkorva, P., Niskanen, E., Kononen, M. & Aikia, M. et al. 3D texture analysis reveals imperceptible MRI textural alterations in the thalamus and putamen in progressive myoclonic epilepsy type 1, EPM1. PLoS ONE 8, e69905 (2013).

Chen, C. Y., Su, H. W., Pai, S. H., Hsieh, C. W., Jong, T. L. & Hsu, C. S. et al. Evaluation of placental maturity by the sonographic textures. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 284, 13–18 (2011).

Hadlock, F. P., Deter, R. L., Harrist, R. B. & Park, S. K. Estimating fetal age: computer-assisted analysis of multiple fetal growth parameters. Radiology 152, 497–501 (1984).

Acharya, G., Wilsgaard, T., Berntsen, G. K., Maltau, J. M. & Kiserud, T. Reference ranges for serial measurements of blood velocity and pulsatility index at the intra-abdominal portion, and fetal and placental ends of the umbilical artery. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 26, 162–169 (2005).

Acharya, G., Wilsgaard, T., Berntsen, G. K., Maltau, J. M. & Kiserud, T. Reference ranges for serial measurements of umbilical artery Doppler indices in the second half of pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 192, 937–944 (2005).

Andescavage, N., duPlessis, A., Metzler, M., Bulas, D., Vezina, G. & Jacobs, M. et al. In vivo assessment of placental and brain volumes in growth-restricted fetuses with and without fetal Doppler changes using quantitative 3D MRI. J. Perinatol. 37, 1278–1284 (2017).

Yushkevich, P. A., Piven, J., Hazlett, H. C., Smith, R. G., Ho, S. & Gee, J. C. et al. User-guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: significantly improved efficiency and reliability. Neuroimage 31, 1116–1128 (2006).

Zou, K. H., Wells, W. M. 3rd, Kikinis, R. & Warfield, S. K. Three validation metrics for automated probabilistic image segmentation of brain tumours. Stat. Med. 23, 1259–1282 (2004).

Alliez Pea. Point set processing. (eds Board C. E.). CGAL User and Reference Manual 2016. https://doc.cgal.org/latest/Manual/how_to_cite_cgal.html.

Kazhdan M., Bolitho, M. & Hoppe, H. Poisson surface reconstruction. In: Proceedings of the Fourth Eurographics Symposium on Geometry Processing. p. 61-70(Eurographics Association Aire-la-Ville, Switzerland, Switzerland 2006).

Dahdouh, S. & Andescavage, N. & Yewale, S. & Yarish, A. & Lanham, D. & Bulas, D. et al. In vivo placental MRI shape and textural features predict fetal growth restriction and postnatal outcome. J Magn Reson Imaging 47, 449–458 (2018).

Ebbing, C., Rasmussen, S. & Kiserud, T. Middle cerebral artery blood flow velocities and pulsatility index and the cerebroplacental pulsatility ratio: longitudinal reference ranges and terms for serial measurements. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 30, 287–296 (2007).

Baschat, A. A. & Gembruch, U. The cerebroplacental Doppler ratio revisited. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 21, 124–127 (2003).

Lane, P. W. Generalized linear models in soil science. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 53, 241–251 (2002).

SAS. SAS system. 9.3 edn. (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, July 2011).

Rothman, K. J. No adjustments are needed for multiple comparisons. Epidemiology 1, 43–46 (1990).

Srinivasan GNaS, G. Statistical texture analysis proceedings of world academy of science. Eng. Technol. 36, 1264–1269 (2008).

Heinonen, S., Taipale, P. & Saarikoski, S. Weights of placentae from small-for-gestational age infants revisited. Placenta 22, 399–404 (2001).

Sanin, L. H., Lopez, S. R., Olivares, E. T., Terrazas, M. C., Silva, M. A. & Carrillo, M. L. Relation between birth weight and placenta weight. Biol. Neonate. 80, 113–117 (2001).

Veerbeek, J. H., Nikkels, P. G., Torrance, H. L., Gravesteijn, J., Post Uiterweer, E. D. & Derks, J. B. et al. Placental pathology in early intrauterine growth restriction associated with maternal hypertension. Placenta 35, 696–701 (2014).

Parra-Saavedra, M., Crovetto, F., Triunfo, S., Savchev, S., Peguero, A. & Nadal, A. et al. Placental findings in late-onset SGA births without Doppler signs of placental insufficiency. Placenta 34, 1136–1141 (2013).

Burton, G. J., Woods, A. W., Jauniaux, E. & Kingdom, J. C. Rheological and physiological consequences of conversion of the maternal spiral arteries for uteroplacental blood flow during human pregnancy. Placenta 30, 473–482 (2009).

Howe, D., Wheeler, T. & Perring, S. Measurement of placental volume with real-time ultrasound in mid-pregnancy. J. Clin. Ultrasound 22, 77–83 (1994).

Hafner, E., Philipp, T., Schuchter, K., Dillinger-Paller, B., Philipp, K. & Bauer, P. Second-trimester measurements of placental volume by three-dimensional ultrasound to predict small-for-gestational-age infants. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 12, 97–102 (1998).

Farina, A. Systematic review on first trimester three-dimensional placental volumetry predicting small for gestational age infants. Prenat. Diagn. 36, 135–141 (2016).

Schwartz, N., Mandel, D., Shlakhter, O., Coletta, J., Pessel, C. & Timor-Tritsch, I. E. et al. Placental morphologic features and chorionic surface vasculature at term are highly correlated with 3-dimensional sonographic measurements at 11 to 14 weeks. J. Ultrasound Med. 30, 1171–1178 (2011).

Schwartz, N., Coletta, J., Pessel, C., Feng, R., Timor-Tritsch, I. E. & Parry, S. et al. Novel 3-dimensional placental measurements in early pregnancy as predictors of adverse pregnancy outcomes. J. Ultrasound Med. 29, 1203–1212 (2010).

Schwartz, N., Wang, E. & Parry, S. Two-dimensional sonographic placental measurements in the prediction of small-for-gestational-age infants. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 40, 674–679 (2012).

Radulescu, E., Ganeshan, B., Minati, L., Beacher, F. D., Gray, M. A. & Chatwin, C. et al. Gray matter textural heterogeneity as a potential in-vivo biomarker of fine structural abnormalities in Asperger syndrome. Pharm. J. 13, 70–79 (2013).

Radulescu, E., Ganeshan, B., Shergill, S. S., Medford, N., Chatwin, C. & Young, R. C. et al. Grey-matter texture abnormalities and reduced hippocampal volume are distinguishing features of schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 223, 179–186 (2014).

Makanyanga, J., Ganeshan, B., Rodriguez-Justo, M., Bhatnagar, G., Groves, A. & Halligan, S. et al. MRI texture analysis (MRTA) of T2-weighted images in Crohn’s disease may provide information on histological and MRI disease activity in patients undergoing ileal resection. Eur. Radiol. 27, 589–597 (2017).

Brown, A. M., Nagala, S., McLean, M. A., Lu, Y., Scoffings, D. & Apte, A. et al. Multi-institutional validation of a novel textural analysis tool for preoperative stratification of suspected thyroid tumors on diffusion-weighted MRI. Magn. Reson Med. 75, 1708–1716 (2016).

Holli, K. K., Waljas, M., Harrison, L., Liimatainen, S., Luukkaala, T. & Ryymin, P. et al. Mild traumatic brain injury: tissue texture analysis correlated to neuropsychological and DTI findings. Acad. Radiol. 17, 1096–1102 (2010).

Walker, M. G., Hindmarsh, P. C., Geary, M. & Kingdom, J. C. Sonographic maturation of the placenta at 30 to 34 weeks is not associated with second trimester markers of placental insufficiency in low-risk pregnancies. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 32, 1134–1139 (2010).

Funding

This was supported by the National Institutes of Health (1U54HD090257, R01-HL116585, UL1TR000075, and KL2TR000076, Clinical-Translational Science Institute-Children’s National).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Andescavage, N., Dahdouh, S., Jacobs, M. et al. In vivo textural and morphometric analysis of placental development in healthy & growth-restricted pregnancies using magnetic resonance imaging. Pediatr Res 85, 974–981 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-019-0311-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-019-0311-1

This article is cited by

-

Influence of maternal psychological distress during COVID-19 pandemic on placental morphometry and texture

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Measuring intrauterine growth in healthy pregnancies using quantitative magnetic resonance imaging

Journal of Perinatology (2022)

-

How and why should the radiologist look at the placenta?

European Radiology (2019)