Abstract

Background

Although children’s curiosity is thought to be important for early learning, the association of curiosity with early academic achievement has not been tested. We hypothesized that greater curiosity would be associated with greater kindergarten academic achievement in reading and math.

Methods

Sample included 6200 children in the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Birth Cohort. Measures at kindergarten included direct assessments of reading and math, and a parent-report behavioral questionnaire from which we derived measures of curiosity and effortful control. Multivariate linear regression examined associations of curiosity with kindergarten reading and math academic achievement, adjusting for effortful control and confounders. We also tested for moderation by effortful control, sex, and socioeconomic status (SES).

Results

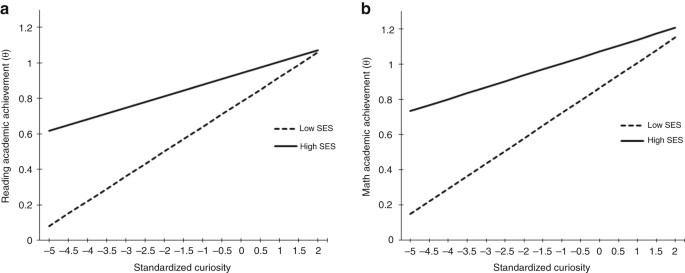

In adjusted models, greater curiosity was associated with greater kindergarten reading and math academic achievement: breading = 0.11, p < 0.001; bmath = 0.12, p < 0.001. This association was not moderated by effortful control or sex, but was moderated by SES (preading = 0.01; pmath = 0.005). The association of curiosity with academic achievement was greater for children with low SES (breading = 0.18, p < 0.001; bmath = 0.20, p < 0.001), versus high SES (breading = 0.08, p = 0.004; bmath = 0.07, p < 0.001).

Conclusions

Curiosity may be an important, yet under-recognized contributor to academic achievement. Fostering curiosity may optimize academic achievement at kindergarten, especially for children with low SES.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fostering early academic achievement in young children has been a longstanding interest of pediatricians and policymakers,1,2,3 with a growing awareness of the importance of social-emotional skills for school readiness.4,5,6,7 The socio-emotional characteristics thought to be necessary for early learning include a child’s capacity for invention and imagination (i.e., curiosity), persistence and attentiveness to tasks (i.e., effortful control), the ability to form and sustain social relationships (i.e., prosocial behavior), and the capacity to manage feelings and behavior (i.e., emotion regulation).2,4,5,6,7,8 Although each of the aforementioned skills is important for school readiness,7 curiosity and effortful control are believed to be especially important for fostering early academic achievement. Although the association between prosocial skills, emotional regulation, and academic achievement is limited,9 we have identified four studies using national datasets that demonstrated an association between curiosity in combination with effortful control (i.e., the construct of ‘approach to learning’) and more optimal early academic achievement in school-age children.9,10,11,12 Although curiosity in combination with effortful control appears to be promotive of early academic achievement, this approach does not examine whether curiosity, independent of effortful control is associated with early academic achievement, which is a gap in the literature. Interventions to foster early learning have largely focused exclusively on the cultivation of early effortful control.13, 14 If higher curiosity, independent of effortful control, is associated with higher early academic achievement, this can provide preliminary support for the importance of fostering children’s curiosity in the preschool years.

Curiosity is characterized by the joy of discovery,15 and the motivation to seek answers to what is unknown.16 Piaget recognized the importance of curiosity as a foundation for early learning, referring to children as ‘little scientists’,17 and accordingly, pediatric guidelines highlight the importance of promoting curiosity as a foundation for early learning.18 Curiosity is described as an approach-oriented, motivational state associated with exploration.19 Curiosity is thought to be a multidimensional construct that is both person-specific (i.e., trait) and situation-specific (i.e., activity-related (state)). Although curiosity traits are thought to be highly heritable,20 and include an openness to experiences, desire for novelty, and willingness to embrace the unexpected,21 the expression of curiosity is also thought to be situational (i.e., state), related to an individual’s idiosyncratic interests, which can vary with activity and context.22 Although little is known about the factors that can promote the development of trait curiosity, it is theorized that state curiosity is malleable, and can be influenced by social and individual contexts. Curiosity is thought to be enhanced when individuals are allowed to engage in activities that are personally meaningful.23 As such, it is believed that interventions which promote an experience of meaningfulness of an activity might enhance a child’s engagement in that activity, and help foster curiosity. Although the association between curiosity and academic achievement has been examined in middle childhood and adolescence,24,25 to our knowledge, there have been no empirical studies examining the independent association of curiosity in early childhood with early academic achievement, which is a gap in the literature. If higher curiosity is associated with higher academic achievement, this can help inform the development of interventions to cultivate curiosity in young children to foster academic achievement. Therefore, the first objective of this study was to test the hypothesis that curiosity at kindergarten is an independent predictor of kindergarten achievement in reading and math.

In addition, we consider the alternate possibility that curiosity may be associated with more optimal early learning only in certain contexts, and that the association between curiosity and academic achievement is moderated by certain characteristics of the child (e.g., effortful control or sex), or certain characteristics of the environment (e.g., socioeconomic status). We chose to examine effortful control as a potential moderator because part of the task of learning requires children to engage in activities that are sometimes not entirely aligned with their interests. Effortful control requires a child to focus attention, delay gratification and inhibit impulses to engage in the tasks that are demanded of them.26 It is possible that a child’s capacity for curiosity and ‘thirst for learning’ will be associated with more optimal academic achievement only if the child is able to manifest focused attention (i.e., effortful control), and that with lower (or absent) effortful control, the association of curiosity with academic achievement is attenuated. We also considered that sex might moderate the association between curiosity and academic achievement. There is some suggestion that teachers perceive curiosity and inquisitiveness as being a ‘behavior problem’.27 If ‘curious boys’ are viewed negatively, the expression of curiosity in boys might be discouraged, contributing to lower academic achievement in boys with higher curiosity. Finally, we consider the possibility that differences in socioeconomic status may moderate the association between curiosity and academic achievement. There is some support that curiosity is valued differently in families of higher versus lower SES.28 We hypothesize that for children in higher SES environments, curiosity may be more valued, encouraged, and supported, contributing to higher academic achievement. Therefore, our second objective was to examine potential moderators of the association between curiosity and academic achievement (effortful control, sex, and SES) and to test the hypotheses that the association between curiosity and academic achievement in reading and math is present in the context of higher effortful control, female sex, and higher SES.

Methods

Study design and sample

Data were drawn from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Birth Cohort (ECLS-B), a nationally representative, population-based longitudinal study sponsored by the US Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) in the Institute for Education Science. The ECLS-B is based on a nationally representative probability sample of children born in the United States in 2001 (inclusive). Data were collected from over 10,000 children and their parents at age 9 months, with subsequent assessments at 24-months, preschool, and kindergarten timepoints, with over 77% of the sample (n = 7700) included at the Kindergarten 2006 timepoint.29 In the ECLS-B, some children entered kindergarten for the first time in 2006, and some entered in 2007. We defined our sample as first-time kindergarten enrollees, from the 2006 and 2007 timepoints. Data collection consisted of home visits with parent interview and direct and indirect child assessments, and included information on children’s cognitive, emotional, behavioral, and physical development across multiple settings.29

For this study, we assessed children at kindergarten entry, including children who first started kindergarten in 2006 (n = 4850) and children who first started kindergarten in 2007 (n = 1500). Our sample excluded children with congenital and chromosomal abnormalities, included children born at 22–41 weeks gestation, and utilized data from 3 timepoints (birth, preschool, and kindergarten). Although there were 6350 children in the combined 2006/2007 kindergarten sample (excluding 100 children with unspecified school placement), our sample was restricted to children who had complete reading, math, and behavioral questionnaire data at kindergarten entry, which reduced our sample size to 6200 children. This study was considered exempt by the Institutional Review Board because the research involved the use of a publicly available dataset, in which the participants were de-identified, and data could not be linked to the participants.

Measures

Outcomes

Academic achievement in kindergarten reading and math

Children were directly assessed at kindergarten age during a home visit by trained National Center for Education Statistics staff using a specialized battery of tests developed for the ECLS-B to assess early reading and math skills. The reading assessment was formulated from existing instruments including the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test, 3rd Edition and Preschool Comprehensive Test of Phonological and Print Processing, and measured markers of early literacy including basic reading skills (letter and word recognition, understanding letter-sound relationships, phonological awareness, sight word recognition, and understanding words in the context of simple sentences). The reliability of the early reading assessment is described by the item response theory (IRT) reliability coefficient, reported as 0.92 at kindergarten. Scores provide ability estimates in a particular domain and were reported as normally distributed theta scores which demonstrated a range of −2.11–3.09 (mean = 0.33, SD = 0.86) at kindergarten.29 The ECLS-B math assessment incorporated items to test the following content areas: number sense, geometry, counting numerical operations, and pattern recognition. The IRT reliability coefficient for the early mathematics assessment was 0.92 at kindergarten. The math theta scores demonstrated a range of −2.42–3.12 (mean = 0.38, SD = 0.80) at kindergarten.29

Predictor

Curiosity and effortful control

Because the ECLS-B did not contain a measure of curiosity or effortful control, we derived these measures from an existing measure of child behavior available in the dataset. The ECLS-B contains a 25-item questionnaire administered to parents and teachers at preschool and kindergarten timepoints, which was designed to assess child behavior.29 The questionnaire was formulated from existing instruments including the Preschool and Kindergarten Behavioral Scales Second Edition (PKBS-2) and Social Skills Rating System (SSRS). Respondents were asked to report the frequency of behaviors observed in the previous 3 months on a 5-point Likert scale (1, never, to 5, very often). Items were reverse coded as appropriate such that higher scores indicated more positive behaviors. Five items from the PKBS-2 were chosen from the parent questionnaire at the kindergarten timepoint to generate our measure of curiosity, and two items were chosen to generate our measure of effortful control that aligned with previous behavioral descriptions of curiosity,30,31,32,33 and effortful control.14, 34 Questions related to curiosity were omitted from the teacher questionnaires and the parent preschool questionnaire. As a result, a curiosity scale could only be generated from the parent at the kindergarten timepoint, and a comparable teacher curiosity scale could not be generated. A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to assure reliability and to calculate the appropriate loading values for deriving curiosity and effortful control factors. Standardized scoring of the curiosity and effortful control factors was conducted using PROC STANDARD, and good internal consistency was demonstrated: curiosity (5 items, α = 0.73), effortful control (2 items, α = 0.67). (Supplemental Table S1).

Covariates

Maternal and child characteristics associated with academic achievement in reading and math35,36,37 were chosen a priori as covariates after a review of the literature. The following covariates were ascertained from the restricted ECLS-B birth certificate data: maternal age, race/ethnicity, marital status (married/ unmarried), birthweight, and gestational age. Also included were measures of maternal education (<high school; high school graduate; and >high school) and poverty (<185% federal poverty limit; ≥185% federal poverty line), which were incorporated into a single composite measure of household socioeconomic status (SES) created by ECLS-B at the kindergarten 2006 timepoint.29 Because early educational experiences and child sex have been associated with kindergarten outcomes,38,39 we included enrollment in any preschool program the year prior to kindergarten entry and child sex as covariates. We also controlled for child age at kindergarten entry, and months of kindergarten experience. Because the number of months of kindergarten experience was not normally distributed, we accounted for the variability in kindergarten experience by creating a 3-category variable indicating the trimester of kindergarten at time of kindergarten assessment (1st trimester Kindergarten: August–October; 2nd trimester Kindergarten: November–January; 3rd trimester Kindergarten: February–June).

Statistical Analyses

Maternal and child characteristics were examined using descriptive statistics. Multiple linear regression (using the SURVEYREG procedure in SAS) was used to examine the associations of curiosity and effortful control generated from the CFA, with academic achievement in reading and math at kindergarten entry. Two models (one model for reading and one model for math) included both curiosity and effortful control simultaneously while controlling for all covariates.

We were also interested in examining whether the association between curiosity and academic achievement was moderated by either effortful control, sex, or socioeconomic status (SES). We ran six additional models (one model for reading and one model for math) to test for moderation which included the interaction terms of curiosity with effortful control (models 1–2); curiosity with sex (models 3–4); and curiosity with SES (models 5–6), controlling for a priori covariates. When the p-value for the interaction was significant (p < .05), we performed a stratified analysis of the association between curiosity and academic achievement, adjusting for covariates.

All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.440 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Because of the complex sample design, sample weights and the Jackknife method were utilized to account for stratification, clustering, and unit non-response, thereby allowing the weighted results to be generalized to the population of U.S. children born in 2001. In accord with the NCES requirements for ECLS-B data usage, reported numbers were rounded to the nearest 50.

Results

Sample Characteristics

After applying sample weights, the maternal and child characteristics were generalizable to the US population in 2001, and the sample characteristics for the weighted sample are shown in Table 1.

Confirmatory factor analyses

The goodness of fit indices for our CFA demonstrated appropriate fit as evidenced by the Standardized RMR (SRMR) = 0.047, and adjusted GFI (AGFI) = 0.91, with good fit indicated by SRMR < 0.08, and AGFI > 0.90. Loading coefficients for each item of the effortful control and curiosity factors were calculated, with loading coefficients > 0.40 indicating that each item contributed to the overall factor. The loading coefficients for each item of the ‘effortful control’ factor was 0.71, and loading coefficients for each item in the 5-item curiosity factor ranged from 0.51 to 0.66. The items ‘likes to try new things,’ ‘shows eagerness to learn new things’, and ‘shows imagination in work and play’ loaded the most strongly on the overall curiosity factor. (Supplemental Table S1).

Association between child curiosity and effortful control and reading and math academic achievement at kindergarten

After controlling for potential confounders, higher curiosity and higher effortful control were each associated with higher reading (breading = 0.11, p < .001 (curiosity); breading = 0.11, p < .001 (effortful control)), and higher math academic achievement at kindergarten (bmath = 0.12, p < .001 (curiosity); bmath = 0.14, p < .001 (effortful control)) (Table 2).

Moderators of the association between child curiosity and effortful control and reading and math academic achievement at kindergarten

The associations between curiosity and academic achievement in reading and math were not moderated by effortful control or sex, as evidenced by non-significant interaction terms (curiosity × effortful control: p = 0.65 (reading academic achievement); p = 0.23 (math academic achievement); curiosity × sex: p = 0.94 (reading academic achievement); p = 0.75 (math academic achievement)). We did find evidence of moderation by SES, in both reading and math models: curiosity × SES: p = 0.01 (reading academic achievement); p = 0.005 (math academic achievement). Because we found evidence of moderation by SES, we performed a covaried analysis of the association between curiosity and academic achievement, for both reading and math, stratified by low and high SES. We found differences in the standardized parameter estimates (b) for the association between curiosity and academic achievement for children from low SES environments, compared to high SES environments for reading academic achievement: (SES ≤ median): b = 0.18, p < 0.001; (SES > median): b = 0.08, p = 0.004. The same association was found for math academic achievement: (SES ≤ median): b = 0.20, p < 0.001; (SES > median): b = 0.07, p < 0.001 (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of ‘curiosity factor’ and associations with reading and math academic achievement

We also performed a post hoc analysis to better understand if there were specific features of the curiosity factor driving the association with reading and math academic achievement at kindergarten that may have particular clinical relevance. The descriptive statistics and standardized parameter estimates (b) for each question comprising the ‘curiosity factor’ are shown in Table 3. We ran two models, one for academic achievement in reading and one for academic achievement in math. Each model included effortful control, and replaced the curiosity factor in in the final model with all 5 question items in the curiosity factor simultaneously, adjusting for the a priori covariates. In these models, ‘shows eagerness to learn new things,’ (breading = 0.09, p < 0.001; bmath = 0.10, p < .001) ‘appropriately uses a variety of words to describe feelings,’ (breading = 0.08, p < 0.001; bmath = 0.07, p < 0.001) and ‘easily adjusts to a new situation,’ (breading = 0.04, p = 0.01; brmath = 0.07, p < 0.001) were each significantly associated with reading and math academic achievement. The questions ‘likes to try new things,’ and ‘shows imagination in work and play,’ were not associated with academic achievement in reading or math in these models (Table 3).

Discussion

This is the first study examining the independent association of curiosity with kindergarten reading and math academic achievement using a nationally representative sample. After controlling for effortful control and other potential confounders, we found that curiosity was significantly associated with academic achievement in kindergarten, with an effect size similar to that for effortful control. These findings suggest that curiosity is as important as effortful control for promoting reading and math academic achievement at kindergarten age. In the absence of controlling for effortful control, previous research has found effect sizes of curiosity on school-age reading and math academic achievement to be higher, with standardized regression coefficients ranging b = 0.16–0.23.41 Although our effect sizes of the association between curiosity and academic achievement are small, and although the strongest predictors for reading and math academic achievement continue to be prior reading and math academic achievement scores,9 our results suggest that curiosity makes a small but meaningful contribution to academic achievement. At an individual level, the effect size of curiosity on academic achievement is small; however, when considered at a population level, the magnitude of effect is notable.

We found that the associations of curiosity with reading and math academic achievement at kindergarten were not moderated by effortful control or sex, but were moderated by SES. These findings suggest that even if a child manifests low effortful control, higher curiosity may be associated with more optimal academic achievement. Currently, most classroom interventions have focused on the cultivation of early effortful control and self-regulatory capacities.42 Our results suggest that an alternate message, focused on the importance of curiosity, may also be considered. Encouragingly, child sex did not moderate the association between curiosity and academic achievement, suggesting that curiosity is equally important in boys and girls for more optimal academic achievement. Although we found evidence that the association of curiosity with academic achievement was moderated by SES, contrary to expectations, we found a differential benefit of curiosity for children with low SES. Our results suggest that while higher curiosity is associated with higher academic achievement in all children, the association of curiosity with academic achievement is greater in children with lower SES. Children with higher SES likely have environments with greater access to resources to foster reading and math academic achievement, whereas children with low SES likely have academic environments that are less enriching, and thus, the drive for academic achievement is related to the child’s motivation to learn (i.e., curiosity).43 Because there is some evidence suggesting that children with low curiosity fail engage with their environments in ways that will foster their academic development,44 and because the association of curiosity and academic achievement appears to have a greater magnitude of association in children from lower SES environments, our results suggest that the promotion of curiosity may be a valuable intervention target to foster early academic achievement,30 with particular advantage for children in poverty.

Because curiosity is thought to relate to the construct of intrinsic motivation, there is some theoretical support that promoting autonomy, feelings of competence, and connectedness can foster intrinsic motivation, and increase curiosity.22 Interventions to foster curiosity in adults have focused on highlighting the personal meaningfulness of an activity to optimize engagement.45 These features may also be helpful in designing interventions to promote curiosity in young children, and is an important area for future research.

Pediatricians, early childhood educators, and policymakers have grappled with the question, ‘what are the early social-emotional skills children need to be successful?’ There has been an increasing interest in the taxonomy of ‘the Big Five character skills’ (i.e., O.C.E.A.N.: Openness to Experience, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism) as a foundation for future life success.46,47,48 One dimension of the Big Five, ‘openness to experience,’ aligns with the item of ‘shows eagerness to learn new things,’ in our curiosity factor, and was associated with higher academic achievement in our adjusted models. When all items were considered together, the aspect of curiosity most strongly associated with higher academic achievement was the construct ‘shows eagerness to learn new things.’ This construct is consistent with some of the earliest descriptions of curiosity as a ‘passion for learning’,49 and speaks to the positive motivational drive for knowledge which underlies curiosity.50 A child’s eagerness to learn may be an important characteristic to nurture in the young child, particularly to promote academic achievement. This framework, consistent with recent neuroscience research, suggests that one pathway to more optimal learning may be through captivating a child’s natural curiosity.51

Our study had several strengths and limitations. The study includes a nationally representative sample, the results of which are generalizable to the population, and direct child assessments of early academic achievement. One of the limitations of the study is that the ECLS-B did not contain data on maternal intelligence quotient, or family history of learning difficulties, which can be associated with early academic achievement. In addition, our construct of curiosity was derived from a parent-report behavioral measure at the kindergarten timepoint. Because the teacher-report of child behavior included different questions, a teacher curiosity factor could not be calculated, and we were not able to examine the construct of curiosity across reporters. Finally, parents generally rated their children very highly in curiosity. Question items about curiosity that generate broader variability in parental response will be an important focus for future work.

Our study provides some preliminary evidence that higher early childhood curiosity, independent of early effortful control, is associated with more optimal early academic achievement, with a greater magnitude of association for children with low SES. To foster early learning, it may be helpful to identify opportunities to cultivate and encourage curiosity in young children, especially for children from environments of economic disadvantage.

Conclusion

We found evidence that curiosity, independent of effortful control, was associated with greater reading and math academic achievement at kindergarten, with a greater magnitude of association for children with low SES. These findings suggest that although effortful control has been emphasized as an important prerequisite for early academic achievement, curiosity is also important, and may be especially important for children from environments of economic disadvantage. In addition, the aspect of curiosity most strongly associated with higher academic achievement was the construct of ‘shows eagerness to learn new things’. Encouraging curiosity in young children and cultivating their eagerness to learn may be a potential intervention target to foster early reading and math academic achievement at kindergarten age, and may be particularly advantageous for children with low SES.

References

High, P. C., the Committee on Early Childhood, Adoption, Dependent Care Council on School Health. School Readiness. Pediatrics 121, e1008–e1015 (2008).

National Education Goals Panel. The Goal 1 Technical Planning Subgroup Report on School Readiness. (National Education Goals Panel, Washington, DC, 1991).

HealthyPeople.gov. Early and Middle Childhood Objectives. Available from: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/early-and-middle-childhood/objectives.

Rimm-Kaufman, S. E. & Pianta, R. C. An ecological perspective on the transition to kindergarten: a theoretical framework to guide empirical research. J. Appl. Dev. Psychol. 21, 491–511 (2000).

Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., Pianta, R. C. & Cox, M. J. Teachers’ judgments of problems in the transition to kindergarten. Early Child. Res. Q. 15, 147–166 (2000).

Abry, T., Latham, S., Bassok, D. & LoCasale-Crouch, J. Preschool and kindergarten teachers’ beliefs about early school competencies: Misalignment matters for kindergarten adjustment. Early Child. Res. Q. 31(Supplement C), 78–88 (2015).

Denham, S. A. Social-emotional competence as support for school readiness: what is it and how do we assess it? Early Educ. Dev. 17, 57–89 (2006).

Kagan S. L., Moore E., Bredekamp S. National Education Goals Panel: Reconsidering Children’s Early Development and Learning Toward Common Views and Vocabulary. DIANE Publishing, Pennsylvania, 1998.

Duncan, G. J. et al. School readiness and later achievement. Dev. Psychol. 43, 1428 (2007).

Lee, E. The relationship between approaches to learning and academic achievement among kindergarten students: an analysis using Early Childhood Longitudinal Study Kindergarten students (ECLS-K). Int. J. Arts & Sci. 5, 305 (2012).

Li-Grining, C. P., Votruba-Drzal, E., Maldonado-Carreño, C. & Haas, K. Children’s early approaches to learning and academic trajectories through fifth grade. Dev. Psychol. 46, 1062–1077 (2010).

Claessens, A., Duncan, G. & Engel, M. Kindergarten skills and fifth-grade achievement: evidence from the ECLS-K. Econ. Educ. Rev. 28, 415–427 (2009).

Diamond, A., Barnett, W. S., Thomas, J. & Munro, S. Preschool program improves cognitive control. Science 318, 1387 (2007).

Blair, C. & Diamond, A. Biological processes in prevention and intervention: the promotion of self-regulation as a means of preventing school failure. Dev. Psychopathol. 20, 899–911 (2008).

Litman, J. A. Interest and deprivation factors of epistemic curiosity. Pers. Individ. Dif. 44, 1585–1595 (2008).

Litman, J. Curiosity and the pleasures of learning: Wanting and liking new information. Cogn. Emot. 19, 793–814 (2005).

Piaget, J. & Cook, M. The origins of intelligence in children. (W W Norton & Co, New York, 1952).

Hagan JF, Shaw JS, Duncan PM (eds). Bright Futures: Guidelines for Health Supervision of Infants, Children, and Adolescents. 4th edn. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2017. https://www.brightfutures.org/tools

Kashdan, T. B. & Silvia, P. J. in Curiosity and interest: The benefits of thriving on novelty and challenge, Oxford handbook of positive psychology. Oxford University Press: USA, 2, 367–374, 2009.

Steger, M. F., Hicks, B. M., Kashdan, T. B., Krueger, R. F. & Bouchard, T. J. Genetic and environmental influences on the positive traits of the values in action classification, and biometric covariance with normal personality. J. Res. Pers. 41, 524–539 (2007).

Kashdan, T. B. et al. The curiosity and exploration inventory-ii: development, factor structure, and psychometrics. J. Res. Personal. 43, 987–998 (2009).

Kashdan, T. B. & Fincham, F. D. Facilitating Curiosity: A Social and Self-Regulatory Perspective for Scientifically Based Interventions. Positive Psychology in Practice. (John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New Jersey, 2004) 482–503.

Black, A. E. & Deci, E. L. The effects of instructors’ autonomy support and students’ autonomous motivation on learning organic chemistry: a self‐determination theory perspective. Sci. Educ. 84, 740–756 (2000).

Froiland, J. M., Mayor, P. & Herlevi, M. Motives emanating from personality associated with achievement in a Finnish senior high school: physical activity, curiosity, and family motives. Sch. Psychol. Int. 36, 207–221 (2015).

Tucker-Drob, E. M., Briley, D. A., Engelhardt, L. E., Mann, F. D. & Harden, K. P. Genetically-mediated associations between measures of childhood character and academic achievement. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 111, 790–815 (2016).

Blair, C. & Razza, R. P. Relating effortful control, executive function, and false belief understanding to emerging math and literacy ability in kindergarten. Child. Dev. 78, 647–663 (2007).

Woods-Groves, S. & Choi, T. Relationship of teachers’ ratings of kindergarteners’ 21st century skills and student performance. Psychol. Sch. 54, 1034–1048 (2017).

Barbarin, O. A. et al. Parental conceptions of school readiness: relation to ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and children’s skills. Early Educ. Dev. 19, 671–701 (2008).

Snow, K. et al. Early Childhood Longitudinal Study, Birth Cohort (ECLS-B) Kindergarten 2006 and 2007 Data File User’s Manual (2010-010). Statistics NCfE. (U.S. Department of Education, Washington, D.C., 2009).

Day, H. I. Curiosity and the interested explorer. Perform. & Instr. 21, 19–22 (1982).

Hall, G.S. & Smith, T.L. Curiosity and interest. Pedagog. Semi. 10, 315–358 (2012).

Maw W. H. A Definition of Curiosity, A Factor Analysis Study. Delaware University, Newark, 1967.

Kidd, C. & Hayden Benjamin, Y. The psychology and neuroscience of curiosity. Neuron 88, 449–460 (2015).

Eisenberg, N, Smith, C.L, Sadovsky, A. & Spinrad, T.L. in Effortful control: relations with emotion regulation, adjustment, and socialization in childhood. In: Baumeister, R.F. & Vohs, K.D. (eds.) Handbook of self-regulation: research, theory, and applications. 259–282 (Guilford Press: New York, 2004).

Resnick, M. B. et al. The impact of low birth weight, perinatal conditions, and sociodemographic factors on educational outcome in kindergarten. Pediatrics 104, e74 (1999).

Poulsen, G. et al. Gestational age and cognitive ability in early childhood: a population-based cohort study. Paediatr. Perinat. Epidemiol. 27, 371–379 (2013).

Larson, K., Russ, S. A., Nelson, B. B., Olson, L. M. & Halfon, N. Cognitive ability at kindergarten entry and socioeconomic status. Pediatrics 135, e440–e448 (2015).

Magnuson, K. A., Ruhm, C. & Waldfogel, J. Does prekindergarten improve school preparation and performance? Econ. Educ. Rev. 26, 33–51 (2007).

Mollborn, S., Lawrence, E., James-Hawkins, L. & Fomby, P. When do socioeconomic resources matter most in early childhood?. Adv. life Course Res. 20, 56–59 (2014).

SAS Institute Inc. Base SAS(R) 9.4 Procedures Guide: Statistical Procedures. (SAS Institute, North Carolina, 2014).

Broussard, S. C. & Garrison, M. E. B. The relationship between classroom motivation and academic achievement in elementary-school-aged children. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 33, 106–120 (2004).

Ursache, A., Blair, C. & Raver, C. C. The promotion of self-regulation as a means of enhancing school readiness and early achievement in children at risk for school failure.Child Dev. Persp. 6, 122–128 (2012).

Deci E. L. & Ryan R. M. Intrinsic motivation: Wiley Online Library. Plenum Publishing Co.: New York, 1975.

Maw, W. H. & Maw, E. W. Self-concepts of high- and low-curiosity boys. Child. Dev. 41, 123–129 (1970).

Markland, D., Ryan, R. M., Tobin, V. J. & Rollnick, S. Motivational interviewing and self–determination theory. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 24, 811–831 (2005).

John, O. P., Caspi, A., Robins, R. W., Moffitt, T. E. & Stouthamer-Loeber, M. The “Little Five”: exploring the nomological network of the five-factor model of personality in adolescent boys. Child. Dev. 65, 160–178 (1994).

Heckman J. J. & Kautz T. Fostering and measuring skills: Interventions that improve character and cognition. No. w19656. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc, 2013.

Kautz T., Heckman J. J., Diris R., Ter Weel B. & Borghans L. Fostering and measuring skills: improving cognitive and non-cognitive skills to promote lifetime success. No. w20749. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc, 2014.

Cicero, H. & Rackham, T. De finibus bonorum el malorum.. (Harvard Press, Cambridge, MA, 1914).

Loewenstein, G. The psychology of curiosity: a review and reinterpretation. Psychol. Bull. 116, 75–98 (1994).

Gopnik, A. Scientific thinking in young children: theoretical advances, empirical research, and policy implications. Science 337, 1623–1627 (2012).

Acknowledgements

University of Michigan, NICHD (K08HD078506), Academy of Zero to Three Fellows. This research was supported by funding from the University of Michigan, NICHD (K08HD078506), and Academy of Zero to Three Fellows to the lead author (PES).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Financial Disclosure: None

Category of Study: Clinical Research

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shah, P.E., Weeks, H.M., Richards, B. et al. Early childhood curiosity and kindergarten reading and math academic achievement. Pediatr Res 84, 380–386 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-018-0039-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-018-0039-3

This article is cited by

-

Environmental Factors Predicting Young Children’s Secure Exploration

Early Childhood Education Journal (2024)

-

Diversity of Intelligence is the Norm Within the Autism Spectrum: Full Scale Intelligence Scores Among Children with ASD

Child Psychiatry & Human Development (2023)

-

How Are Curiosity and Interest Different? Naïve Bayes Classification of People’s Beliefs

Educational Psychology Review (2022)

-

Social class and subjective well-being in Chinese adults: The mediating role of present fatalistic time perspective

Current Psychology (2022)

-

Exploratory behaviour towards novel objects is associated with enhanced learning in young horses

Scientific Reports (2021)