Abstract

Gastric neoplasms exhibiting oxyntic gland differentiation typically are composed of cells with mild cytonuclear atypia differentiating to chief cells and to a lesser extent, parietal cells. Such tumors with atypical features have been reported also and terminology for this entity remains a matter of considerable debate. We analyzed and classified 26 tumors as oxyntic gland neoplasms within mucosa (group A, eight tumors) and with submucosal invasion. The latter was divided further into those with typical histologic features (group B, 14 tumors) and atypical features, including high-grade nuclear or architectural abnormality and presence of atypical cellular differentiation (group C, four tumors). Groups A and B tumors shared similar histologic features displaying either a chief cell predominant pattern characterized by monotonous chief cell proliferation, or a well-differentiated mixed cell pattern showing admixture of chief and parietal cells resembling fundic gland. In addition, group C tumors displayed atypical cellular differentiation, including mucous neck cell and foveolar epithelium. Moderate or even marked cytological atypia was noted in group C, whereas it was usually mild in the other groups except for three group B tumors with focal moderate atypia. More than 1000 μm submucosal invasion and lymphovascular invasions were recognized only in group C. Mutation analyses identified KRAS mutation in one group C tumor as well as GNAS mutation in in one group A and group B tumors. Intramucosal tumors appear to behave biologically benign and should be classified as “oxyntic gland adenoma”. Those with submucosal invasion also have low malignant potential; however, a subset will have atypical features associated with aggressive histologic features and should be designated as “adenocarcinoma of fundic gland type”. Especially, we suggest “adenocarcinoma of fundic gland mucosa type” for tumors with submucosal invasion exhibiting atypical cellular differentiation, because the feature is likely to be a sign of aggressive phenotype.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastric neoplasia with oxyntic gland differentiation was reported first by Tukamoto et al. [1], and later proposed as a new entity of gastric adenocarcinoma by Ueyama et al. [2], who proposed the designation “gastric adenocarcinoma of fundic gland type”. These as well as later reports have suggested that the majority of this type of gastric neoplasm are limited within mucosa or superficial submucosa, slow growing, and follow a rather benign clinical course [2, 3]. The terminology for this entity is contradictory and the descriptive term “oxyntic gland polyp/adenoma” [3] was proposed also, especially for lesions confined to the mucosa.

On the other hand, such tumors with atypical histologic features have been reported also. For example, massive lymphovascular invasion with intravenous subserosal spread was noted, although lymphovascular invasion typically is absent in oxyntic gland neoplasms [4]. Therefore, there remains considerable debate whether such lesions should be called adenocarcinoma or adenoma/polyp. Unfortunately, a standard therapeutic approach for this type of gastric tumor has not been established because of its heterogeneous nature and inconsistent terminology.

Therefore, we attempted to characterize this group of gastric neoplasms better and determine whether clinically relevant subclassification of this entity can be performed.

Material and methods

Case selection

A pathologic review was performed of primary gastric neoplasms in the pathology file at Tokyo University Hospital that were diagnosed as early gastric cancer between 2011 and 2018. We identified 24 tumors from 22 patients exhibiting oxyntic gland differentiation in at least a portion of the tumor, as well as two additional cases from the consultation file of one author (MF). Therefore, a total of 26 tumors from 24 patients were studied.

The institutional review board of the Tokyo University Hospital approved the study.

Clinical data

Demographic data, endoscopic findings, and clinical follow-up information were obtained by review of the medical records. The endoscopic tumor appearance was classified according to the criteria of the World Health Organization classification for early gastric cancer [5].

Pathologic assessment

Hematoxylin and eosin-stained sections were available in all cases and were reviewed initially. We evaluated all tumors for lesion size, depth of invasion, lymphovascular invasion, cellular phenotype, degree of nuclear atypia, and background mucosal condition. In terms of cellular phenotype, we classified tumors with typical histologic features based on the two major patterns recognized previously: a chief cell predominant pattern characterized by monotonous chief cell proliferation, and a well-differentiated mixed cell pattern showing admixture of chief and parietal cells bearing a resemblance to fundic glands [6]. Nuclear atypia was recorded semiquantitatively by evaluating the degree of nuclear enlargement as follows: mild (5–9 μm-sized round or ovoid nuclei), moderate (10–15 μm-sized round or ovoid nuclei), and marked (>15 μm-sized, significant pleomorphism, or prominent nucleoli with clearing of chromatin).

The criteria for further classification were established in this study based on the histologic features. Tumors were classified as oxyntic gland neoplasms limited within mucosa (group A) and those with submucosal involvement (group B, with typical histologic features and group C, with atypical features, including more than a mild degree of nuclear or architectural abnormality, and presence of atypical cellular differentiation, such as mucous neck cell and foveolar epithelium in addition to chief cell and parietal cells).

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded tissue blocks were available for immunohistochemical evaluation in 24 of 26 tumors. Cell differentiation markers were used to confirm chief cell (pepsinogen-I: clone 8003, 1:500; Bio-Rad, CA), parietal cell (H+/K+-ATPase: clone 2B6, 1:200; Fitzgerald Industries International, MA), foveolar epithelium (MUC5AC: CLH2, 1:200; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, TX), and mucous neck cell (MUC6: CLH5, 1:100; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) differentiation.

Immunohistochemical staining was performed using a Ventana Benchmark XT autostainer (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, USA) with the labeled streptavidin–biotin peroxidase method, and the signals were visualized with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine.

Mutation analysis

Hot spot mutations in GNAS and KRAS genes were analyzed in 21 of 26 tumors with available and sufficient material. In addition, to discover novel mutations in group C tumors, this group tumors were analyzed for mutations in hotspot regions of 50 oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes using next-generation sequencing. The detailed procedures for molecular analyses are described in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Methods.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were compared using Student’s t-test and categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test (JMP Pro 11 software; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Differences were considered significant when the P value from the two-tailed test was < 0.05.

Results

Based on histologic evaluation, 26 tumors were classified into group A (n = 8, intramucosal tumor), group B (n = 14, submucosal invasive tumor with typical histologic features), and group C (n = 4, submucosal invasive tumors with atypical histologic features). Table 1 displays clinical and pathological findings in the 26 tumors.

Clinical findings

Patient ages ranged from 41 to 85 years (mean, 66; median, 67) with a male-to-female ratio of 3:1 (18:6). Most of the tumors were identified within the upper (n = 20, 77%) or middle (n = 4, 15%) third of the stomach, and the remaining two (8%) were in the remnant stomach after distal gastrectomy with Billroth II reconstruction for a duodenal ulcer (#15 and #23).

Endoscopically, 20 of 26 (77%) tumors showed an elevated lesion exhibiting a submucosal tumor-like appearance (Fig. 1a). Central depression was noted also in four groups B (#21) and C (#23, 25, and 26) tumors. Six (23%) tumors had a flat or slightly depressed appearance (Fig. 1b). Dilated vessels at the tumor surface were characteristically noted in 17 (65%) tumors: four (50%) in group A, 12 (86%) in group B, and one (25%) in group C (Fig. 2a). Tumor size ranged from 3 to 40 mm and was significantly larger in group C (mean, 26.8 mm) compared to groups A and B (mean, 5.9 and 7.4 mm, respectively; P < 0.0001 for both).

Oxyntic gland neoplasm with typical histologic features. Representative endoscopic images show a small elevated lesion with submucosal tumor-like appearance (a) and a depressed lesion (b). Chief cell predominant pattern (×400) (c), and its eosinophilic variant (×400) (d). Well-differentiated mixed cell pattern (×200) (e). Multilayered and nuclear stratification (×400) (f).

Oxyntic gland neoplasm with submucosal invasion. a Endoscopic image shows submucosal tumor-like lesion with dilated vessels on the surface. b Histologic picture at low magnification shows submucosal invasion (×50). c Higher power of submucosal invasive area [in the left part of b] showing glandular proliferation with moderate nuclear atypia in the submucosal (×600). d Intramucosal area [in the right part of b] is composed of typical chief cell predominant pattern with mild nuclear atypia (×600)

In groups A and B, endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) was performed for the majority of tumors (20 of 22, 91%). The remaining two tumors (#6, #18) were resected via nonexposed endoscopic wall inversion surgery (NEWS) [7].

In group C, patients underwent surgical resection (#25 and #23 via total and segmental gastrectomy, respectively), and ESD followed by additional surgery, including total (#24) and segmental (#26) gastrectomy for the remnant stomach.

Pathologic features

Groups A and B tumors had typical morphologic features of oxyntic gland neoplasm, which have been well described in the literature [2, 3, 6, 8]. Twelve of 22 tumors (55%) showed a chief cell predominant pattern characterized by glandular proliferation of monotonous columnar cells with pale basophilic cytoplasm differentiating to chief cells (Fig. 1c). These cells were positive for pepsinogen-I on immunohistochemistry. MUC6 positive staining was also seen in most tumors in various degrees. In this pattern, cells with parietal cell differentiation were rare and scattered, especially in the superficial part of the tumor, which was highlighted by H+/K+-ATPase immunostaining. Five tumors with this pattern were composed predominantly of columnar cells with eosinophilic granular cytoplasm (eosinophilic variant; Fig. 1d). Six of 22 tumors (27%) had a well-differentiated mixed cell pattern characterized by admixture of chief and parietal cells closely resembling fundic gland (Fig. 1e). Both patterns were noted in four tumors (18%). Multilayered and nuclear stratification was recognized in 10 tumors (Fig. 1f). Regarding the nuclear features, all group A tumors had mild nuclear atypia. Group B tumors also essentially showed mild nuclear atypia; however, three (21%) had focal moderate nuclear atypia, especially at the central area exhibiting submucosal invasion (Fig. 2).

Group C tumors were composed also of glandular proliferation of columnar neoplastic cells with chief and parietal cell differentiation at least partly, but also had atypical morphologic features that were not seen in groups A and B. Endoscopic and histologic features of the four tumors in group C are demonstrated in Figs. 3–6.

Tumor with atypical features (group C, #23). a Endoscopic image. b Low magnification shows massive submucosal invasion (×20). c Higher power showing intramucosal glandular proliferation with mild nuclear atypia (×400). d Higher power of submucosal invasive area composed of glandular proliferation differentiating to fundic gland (×200). e Pepsinogen-I immunostain demonstrate chief cell differentiation [same field as d] (×200). f Neoplastic cells with parietal cell differentiation are highlighted with immunohistochemistry of H+/K+-ATPase [same field as d] (×200)

Tumor with atypical features (group C, #24). a Endoscopic image. Arrows indicate the depressed lesion. b Low magnification showing invasive growth involving the submucosa (×40). c More complex architectural abnormality is noted compared to that of typical example (×400). d Higher power showing low-columnar-to-cuboidal neoplastic cells resembling to chief cell and parietal cells (×600). Pepsinogen-I (×400) (e) and H+/K+-ATPase (×400) (f) immunostains highlight neoplastic cells differentiating to chief cell and parietal cell, respectively [same field as c]

Tumor with atypical features (group C, #25). a Endoscopic image. b This tumor is composed heterogeneous components as shown in low magnification (×40). c Pepsinogen-I immunostain highlights tumor component with chief cell differentiation in the submucosal invasive area in the right (d) and intramucosal area in the left (e) (×40). d Higher power of the submucosal invasive area demonstrating chief cell or mucous neck cell differentiation as well as foveolar differentiation in the mucosa (×100). e Higher power of intramucosal component showing well-differentiated mixed cell pattern with marked nuclear atypia with prominent nucleoli and nuclear clearing (×600). f H+/K+-ATPase immunostain highlighted parietal cell differentiation [same field as e] (×600)

Tumor with atypical features (group C, #26). a Endoscopic image. b Low power picture showing massive submucosal invasion of distended neoplastic glands (×20). c Intramucosal tumor component is composed of packed glandular proliferation (×100). d In higher power, neoplastic cells are predominantly composed of parietal cells and mucous neck cells (×400). e Parietal cell differentiation is confirmed by H+/K+-ATPase immunostain [same field as d] (×400). f Focal chief cell differentiation is demonstrated by pepsinogen-I immunostain (×400)

The first tumor (#23) was composed of neoplastic cells with mucous neck cell differentiation in a significant proportion (~40% of neoplastic cells) as well as those with chief and parietal cell differentiation (Fig. 3). This tumor showed mild-to-moderate nuclear atypia and massive submucosal involvement.

The second tumor (#24) had marked architectural abnormality showing complex anastomosing glandular or trabecular proliferation and an apparently invasive growth pattern with massive submucosal involvement and stromal fibrosis (Fig. 4a–c). On higher magnification, the low-columnar-to-cuboidal neoplastic cells bear a resemblance to chief and parietal cells, which was confirmed by immunohistochemistry of pepsinogen-I and H+/K+-ATPase (Fig. 4d–f). Differentiation to mucous neck cell and foveolar epithelium also was focally recognized in this tumor.

The third tumor (#25) was composed also of a heterogeneous component differentiating to foveolar epithelium and mucous neck cell phenotype in addition to chief and parietal cells (Fig. 5). This tumor had a well-differentiated mixed cell pattern in the mucosal component with moderate and focal marked nuclear atypia showing nuclear clearing and prominent nucleoli (Fig. 5e, f). In the other area, foveolar differentiation was prominent in the mucosa, and chief and mucous neck cell differentiation was noted in the submucosa (Fig. 5c, d).

The last tumor (#26) was composed predominantly of mucous neck and parietal cell lineages and showed massive submucosal invasion (Fig. 6). Distended glandular proliferation was noted in the submucosa. Chief cell differentiation was also focally recognized.

Lymphovascular invasion was noted in two tumors (#23 and #26); however, none had lymph node metastasis.

Background mucosal condition

Two patients (#15 and #23) had a history of distal gastrectomy with Billroth II reconstruction for duodenal ulcer, and the remnant stomach had mild remnant gastritis with reactive gastropathy. Adjacent mucosae of the other 24 tumors were essentially normal with no Helicobacter pylori gastritis, atrophy, or intestinal metaplasia, although eight patients had a history of H. pylori eradication. In one tumor (#8), parietal cell hypertrophy was noted in the adjacent mucosa secondary to proton pump inhibitor therapy for gastroesophageal reflux disease.

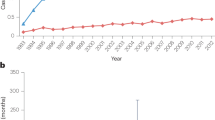

Clinical course

In four group A tumors (#2, 6, 7, 8), >1 year (18, 20, 48, and 78 months) elapsed from the first endoscopic detection of the lesion to endoscopic treatment. Notably, there were minimal changes in the endoscopic appearance, including tumor size, between the first examination and resection in three cases, although the size increased from 4 to 8 mm in one case during 48 months. Histologic evaluation of the resection specimens revealed that all four tumors remained intramucosal.

Clinical follow-up information after resection was available for 25 patients (median follow-up, 32 months; range, 3–97); no tumors recurred nor metastasized.

Molecular findings

Hot spot GNAS mutations were identified in two tumors: one of six (16.7%) group A tumors (case #8, c.602 G > A) and in one of 11 (9.1%) group B tumors (case #17, c.601 C > T). KRAS mutation was detected in one tumor of group C (case #23, c.182 A > T).

Next-generation sequencing for group C tumors was successfully performed in two of four group C tumors (#23 & 26). The remaining two tumors (#24 and 25) could not be tested in this analysis due to poor quality of DNA. In this analysis of hot spot mutations of 50 cancer –related genes, only KRAS mutation (c.182 A > T) was identified in one tumor (#23) (Supplementary Table 2), which was consistent with the result by Sanger sequencing. There was no other nonsynonymous mutation identified in this tumor. The other tumor (#26) harbored no nonsynonymous mutation in this analysis.

Discussion

We present one of the largest case series of oxyntic gland neoplasm with special focus on tumors with atypical histologic features. Earlier studies have well-described clinicopathological features of typical examples of oxyntic gland neoplasm composed of chief and parietal cells with mild nuclear atypia [2, 3, 8]. According to these reports, such a tumor appears to behave biologically benign, because it lacks deeper invasion, lymphovascular invasion, and metastasis. However, based on our observations, a small subset of such tumors had atypical histologic features, and massive submucosal invasion and even lymphovascular invasion developed. Consequently, the particular importance of this study is it demonstrated that oxyntic gland neoplasms include a subset of tumors that is likely to be more aggressive than typical examples.

Tumors limited within mucosa (group A) always are small (2–9 mm), have mild cytonuclear atypia, and are highly likely to behave as biologically benign based on our observations as well as those of prior reports [2, 3, 8]. As further evidence of its indolent behavior, half of the group A tumors in our series remained intramucosal with only limited progression on long-term preoperative follow-up (18, 20, 48, and 78 months). This observation is indirectly supported by earlier reports of a low Ki67-labeling index in this subtype [2, 3, 8]. In the light of these characteristics, we proposed designating these intramucosal tumors as “oxyntic gland adenoma”. However, intramucosal tumors with severe cytological and/or architectural abnormality invading in the lamina propria would be classified as intramucosal adenocarcinoma of fundic gland type, although such a case has not been reported so far. It appears that “oxyntic gland adenoma” can be treated with endoscopic resection.

Tumors with submucosal invasion appear to preserve a low-grade malignancy profile as long as atypical histologic features are absent. Similar to group A tumors, Abe et al. and Sato et al. [9, 10] reported tumors with minimal submucosal invasion exhibiting little morphologic change on endoscopic examinations for 5 and 12 years, respectively. However, it is noteworthy that a subset of group B tumors in our series showed focal increased nuclear atypia at the submucosal invasive area. Hidaka et al. [11] also presented a tumor showing transformation into high-grade adenocarcinoma from typical oxyntic gland neoplasm with mild nuclear atypia. Vascular invasion was noted also in this atypical case. These findings suggest a heightened risk of malignant transformation in this group, which then might acquire a more aggressive behavior. At this time, we proposed designating the tumor with submucosal invasion as “adenocarcinoma of fundic gland type”, because there are insufficient data to make definitive criteria to predict malignant potential for this group. Pathologists would need careful evaluation for assessment of submucosal invasion, because oxyntic gland neoplasms might show prolapse-type misplacement rather than true submucosal invasion [3]. In the absence of deep or lymphovascular invasion, endoscopic resection or minimally-invasive surgical techniques, such as combined laparoscopic and endoscopic approaches to neoplasia with a nonexposure technique (CLEAN-NET) [12] or NEWS [7], the latter performed for two of our cases, seems adequate treatment and will afford cure for group B tumors at low risk of lymph node metastasis.

Several examples of oxyntic gland neoplasm with atypical histologic features, corresponding to group C tumors in our series, have been reported recently. Ueo et al. [4, 13] reported a case showing massive lymphovascular invasion with intravenous subserosal spread. Of note, the histologic pictures illustrated in this report were very similar in morphology to those of a group C tumor (#24) in our series, showing complex anastomosing glandular proliferation of low-columnar-to-cuboidal cells differentiating to fundic gland. This tumor also showed atypical cellular differentiation, including mucous neck cell and foveolar epithelium [13]. Among a case series by Ueyama et al. [14] (n = 10), only the largest tumors (31 mm) showed massive submucosal invasion (1200 μm) and lymphatic invasion, and notably this tumor had an atypical immunophenotype positive for CD10 (intestinal marker) as well as fundic gland markers (pepsinogen-I, MUC6, and focal H+/K+-ATPase). These reports as well as our observations suggested that oxyntic gland neoplasms can have atypical histologic features, such as high-grade cytonuclear atypia, marked architectural abnormality, and atypical cellular differentiation, as the tumor progress. Importantly, these atypical features are closely associated with aggressive biological behavior, such as lymphovascular and deep submucosal invasion. In the Japanese literature, even lymph node metastasis was noted in an oxyntic gland tumor with atypical features [15]. Some authorities called such tumors with atypical features “adenocarcinoma of fundic gland mucosa type”, because these tumors have cellular phenotypes that are present in normal fundic gland mucosa, including foveolar epithelium and mucous neck cells as well as chief and parietal cells [16, 17]. We would suggest “adenocarcinoma of fundic gland mucosa type” for group C tumors, because this term seems reasonable to emphasize the association between atypical cellular differentiation and aggressive histological features. Surgical resection with lymphadenectomy should be considered for these atypical tumors, although larger sample size and longer follow-up are necessary to verify the malignant potential including the risk of nodal metastasis in this group.

Whether tumors of each group in our study represent a morphologic continuing spectrum of disease or a biologically heterogeneous subgroup needs further studies in a larger cohort. In addition, it would be important to clarify the molecular basis of oxyntic gland neoplasms in each group. Previous studies detected mutation in CTNNB1, AXINs, APC, or GNAS in approximately a half of oxyntic gland neoplasms and suggested that activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway might have a role in its carcinogenesis [11, 18]. In our series, activating GNAS mutations were identified in one of six (16.7%) group A and one of 11 (9.1%) group B tumors, in line with the frequency (19.2%) reported by Nomura et al. [18]. In addition, activating KRAS mutation was detected in one of the two group C tumors analyzed in this study. Of note, Nomura et al. also reported KRAS mutations in two of 26 (7.7%) tumors including the largest tumor with lymphatic invasion and tumor with deepest submucosal invasion in their series [18]. These observations suggest that KRAS mutation might be associated with aggressive phenotype in oxyntic gland neoplasm, although conclusive results were not derived due to small sample size. Additional molecular alterations associated with atypical histologic features and high-grade transformation must be clarified.

In conclusion, oxyntic gland neoplasms limited within mucosa appear to behave as biologically benign and should be classified as “oxyntic gland adenoma”. Those with submucosal invasion also have low malignant potential; however, a subset will have atypical features associated with aggressive histologic features, and should be designated as “adenocarcinoma of fundic gland type”. Especially, we suggest “adenocarcinoma of fundic gland mucosa type” for tumors with submucosal invasion exhibiting atypical cellular differentiation, such as differentiation to foveolar epithelium and mucous neck cell, because the feature is likely to be a sign of aggressive phenotype.

References

Tsukamoto T, Yokoi T, Maruta S, Kitamura M, Yamamoto T, Ban H, et al. Gastric adenocarcinoma with chief cell differentiation. Pathol Int. 2007;57:517–22.

Ueyama H, Yao T, Nakashima Y, Hirakawa K, Oshiro Y, Hirahashi M, et al. Gastric adenocarcinoma of fundic gland type (chief cell predominant type): proposal for a new entity of gastric adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:609–19.

Singhi AD, Lazenby AJ, Montgomery EA. Gastric adenocarcinoma with chief cell differentiation: a proposal for reclassification as oxyntic gland polyp/adenoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:1030–5.

Ueo T, Yonemasu H, Ishida T. Gastric adenocarcinoma of fundic gland type with unusual behavior. Dig Endosc. 2014;26:293–4.

Bosman FT, World Health Organization., International Agency for Research on Cancer. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. 4th ed. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010.

Benedict MA, Lauwers GY, Jain D. Gastric adenocarcinoma of the fundic gland type: update and literature review. Am J Clin Pathol. 2018;149:461–73.

Mitsui T, Niimi K, Yamashita H, Goto O, Aikou S, Hatao F, et al. Non-exposed endoscopic wall-inversion surgery as a novel partial gastrectomy technique. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17:594–9.

Chan K, Brown IS, Kyle T, Lauwers GY, Kumarasinghe MP. Chief cell-predominant gastric polyps: a series of 12 cases with literature review. Histopathology. 2016;68:825–33.

Sato Y, Fujino T, Kasagawa A, Morita R, Ozawa SI, Matsuo Y, et al. Twelve-year natural history of a gastric adenocarcinoma of fundic gland type. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2016;9:345–51.

Abe T, Nagai T, Fukunaga J, Okawara H, Nakashima H, Syutou M, et al. Long-term follow-up of gastric adenocarcinoma with chief cell differentiation using upper gastrointestinal tract endoscopy. Intern Med. 2013;52:1585–8.

Hidaka Y, Mitomi H, Saito T, Takahashi M, Lee SY, Matsumoto K, et al. Alteration in the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway in gastric neoplasias of fundic gland (chief cell predominant) type. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:2438–48.

Kato M, Uraoka T, Isobe Y, Abe K, Hirata T, Takada Y, et al. A case of gastric adenocarcinoma of fundic gland type resected by combination of laparoscopic and endoscopic approaches to neoplasia with non-exposure technique (CLEAN-NET). Clin J Gastroenterol. 2015;8:393–9.

Ueo T, Yonemasu H, Ishida T, Iwaki K, Yao K, Yao T, et al. Advanced stage of gastric adenocarcinoma of fundic gland type with venous invasion in the subserosa, report of a case. Stomach Intest. 2015;50:1566–72.

Ueyama H, Matsumoto K, Nagahara A, Hayashi T, Yao T, Watanabe S. Gastric adenocarcinoma of the fundic gland type (chief cell predominant type). Endoscopy. 2014;46:153–7.

Ueyama H, Yao T, Matsumoto K, Tanaka I, Komori H, Akazawa Y, et al. Establishment of endoscopic diagnosis for gastric adenocarcinoma of fundic gland type (chief cell predominant type) using magnifying endoscopy with narrow-band imaging. Stomach Intest. 2015;50:1533–47.

Takahashi K, Fujiya M, Ichihara S, Moriichi K, Okumura T. Inverted gastric adenocarcinoma of fundic gland mucosa type colliding with well differentiated adenocarcinoma: a case report. Med (Baltim). 2017;96:e7080.

Uchida A, Ozawa M, Ueda Y, Murai Y, Nishimura Y, Ishimatsu H, et al. Gastric adenocarcinoma of fundic gland mucosa type localized in the submucosa: a case report. Med (Baltim). 2018;97:e12341.

Nomura R, Saito T, Mitomi H, Hidaka Y, Lee SY, Watanabe S, et al. GNAS mutation as an alternative mechanism of activation of the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway in gastric adenocarcinoma of the fundic gland type. Hum Pathol. 2014;45:2488–96.

Acknowledgements

We thanks Kimiko Takeshita and Aiko Nishimoto for technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ushiku, T., Kunita, A., Kuroda, R. et al. Oxyntic gland neoplasm of the stomach: expanding the spectrum and proposal of terminology. Mod Pathol 33, 206–216 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-019-0338-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-019-0338-1

This article is cited by

-

A case of gastric adenocarcinoma with pyloric gland-type infiltrating submucosa

Surgical Case Reports (2024)

-

Transcriptome analysis reveals the essential role of NK2 homeobox 1/thyroid transcription factor 1 (NKX2-1/TTF-1) in gastric adenocarcinoma of fundic-gland type

Gastric Cancer (2023)

-

SP70 is a potential biomarker to identify gastric fundic gland neoplasms

World Journal of Surgical Oncology (2022)

-

Endoscopic features of oxyntic gland adenoma and gastric adenocarcinoma of the fundic gland type differ between patients with and without Helicobacter pylori infection: a retrospective observational study

BMC Gastroenterology (2022)

-

The updated WHO classification of digestive system tumours—gastric adenocarcinoma and dysplasia

Der Pathologe (2022)