Abstract

The phase stability of an optical coherence elastography (OCE) system is the key determining factor for achieving a precise elasticity measurement, and it can be affected by the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), timing jitters in the signal acquisition process, and fluctuations in the optical path difference (OPD) between the sample and reference arms. In this study, we developed an OCE system based on swept-source optical coherence tomography (SS-OCT) with a common-path configuration (SS-OCECP). Our system has a phase stability of 4.2 mrad without external stabilization or extensive post-processing, such as averaging. This phase stability allows us to detect a displacement as small as ~300 pm. A common-path interferometer was incorporated by integrating a 3-mm wedged window into the SS-OCT system to provide intrinsic compensation for polarization and dispersion mismatch, as well as to minimize phase fluctuations caused by the OPD variation. The wedged window generates two reference signals that produce two OCT images, allowing for averaging to improve the SNR. Furthermore, the electrical components are optimized to minimize the timing jitters and prevent edge collisions by adjusting the delays between the trigger, k-clock, and signal, utilizing a high-speed waveform digitizer, and incorporating a high-bandwidth balanced photodetector. We validated the SS-OCECP performance in a tissue-mimicking phantom and an in vivo rabbit model, and the results demonstrated a significantly improved phase stability compared to that of the conventional SS-OCE. To the best of our knowledge, we demonstrated the first SS-OCECP system, which possesses high-phase stability and can be utilized to significantly improve the sensitivity of elastography.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Optical coherence elastography (OCE) is an emerging functional imaging technique that quantifies the elasticity of biological tissue by using Doppler optical coherence tomography (OCT) to measure the local tissue displacement as a function of the applied stress1,2. Compared with conventional elastography (e.g., magnetic resonance elastography, ultrasound elastography, and Brillouin microscopy), OCE possesses micron-level resolution and axial displacement sensitivity on the order of subnanometres and therefore has become an attractive research tool for ophthalmology, dermatology, cardiology, and oncology3,4,5,6,7,8,9.

Since OCE relies on the measuring phase via Doppler OCT, the phase stability of the imaging system is the key factor determining its performance10,11,12. Most OCE systems utilizing the acoustic radiation force (ARF) as a tissue excitation method are reported to have the capability of detecting displacements in the range of hundreds of nanometers. In those cases, a relatively strong ARF is necessary to accurately reconstruct the elastic wave propagation, and this force may exceed the ophthalmic mechanical index (MI) safety standard of 0.23 approved by the Food and Drug Administration13,14,15. An OCE system with ultrahigh displacement sensitivity will be able to scale down the applied ARF by at least 1 order of magnitude while maintaining a sufficient signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), which will reduce the required ARF such that it is within the range of the MI safety standard to facilitate the clinical translation of OCE in ophthalmology. The common-path configuration, as an optical method, addresses the phase instability caused by environmental vibration that leads to a fluctuating optical path difference (OPD) between the reference and sample arms. Additionally, the common-path configuration provides intrinsic compensation for polarization mismatch and dispersion mismatch between the sample and reference arms16,17,18. In 2017, Lan et al. reported a high-phase-stability OCE system using a common-path spectral-domain OCT (SD-OCT) to achieve a subnanometre displacement sensitivity, demonstrating the feasibility of common-path OCE; however, only phantom experiments were performed19. In addition, SD-OCT-based OCE systems are based on a static operation principle that provides phase-stable detection15,20,21,22,23,24, but their performance is limited by the groove density of the diffraction grating, the center wavelength of the light source, and the resolution of the line-scan camera, hence the inherent disadvantages of phase washout, low imaging speed, shallow penetration depth, and short imaging range25,26.

In contrast, swept-source optical coherence tomography (SS-OCT), which can be operated with a much narrower instantaneous linewidth, longer center wavelength, higher repetition rate, and balanced detection, has the capability of providing a long imaging range, deep penetration depth, high imaging speed, and reduced fringe washout. Nevertheless, the phase stability of SS-OCT suffers from fluctuations in the mechanical movement of the sweeping laser; thus, a proper synchronization between the data acquisition and laser sweep is crucial in achieving a high-phase stability in a swept-source system27. A lambda (λ) trigger using a fiber Bragg grating (FBG) as well as a k-clock generated by a Mach-Zehnder interferometer (MZI) have been introduced to improve the phase stability, making SS-OCT a more attractive setup in OCE applications28. In recent years, several OCE systems based on conventional SS-OCT (SS-OCECOV) have been proposed14,29,30,31,32,33,34,35, and their feasibilities have been validated through ex vivo and in vivo experiments, demonstrating great potential towards clinical translation. Although these studies have reported subnanometre displacement sensitivities, this is achieved only in system charaterization where a simple common-path configuration is used. The system performance of SS-OCECOV is degraded when performing measurements because the phase fluctuation between the sample and reference arms is not negligible in conventional OCE. Furthermore, the reported SNR and phase stability are usually from the averages of several measurements36. Despite current advancements in SS-OCT, achieving a phase sensitivity on the order of subnanometres from actual experiments using SS-OCE remains challenging.

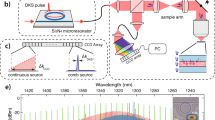

In our study, we designed and implemented a high-phase-stable OCE system using a common-path SS-OCT (SS-OCECP). A 3-mm thick, 30-arcmin wedged glass window (WW10530, Thorlabs, Inc., NJ) was incorporated distal to the scan lens to generate two reference signals, each from one of the surfaces of the window. This setup allows for the simultaneous generation of two OCT interference signals in two different frequency domains, which can be averaged for an enhanced SNR and reduced speckle. This averaging method is not achievable in SD-OCT due to the limited imaging range. Furthermore, the common-path configuration minimizes the differences between the sample and the reference arm, thereby providing stable phase information for precision displacement measurement. In addition to the optical method, data acquisition and synchronization were optimized to accurately retrieve the phase information. In this report, we first compared the phase performance of SS-OCECP with that of SS-OCECOV. Then, a tissue-mimicking phantom model and an in vivo rabbit model were imaged to validate the SS-OCECP performance.

Results

Phase stability quantification

To measure the phase stability of our SS-OCECP, a 1.0-mm microscope slide was placed at the focus of the objective lens to generate autocorrelation interference by the back-reflected light from the front and back surfaces of the slide. In our SS-OCECOV counterpart, a gold mirror was placed at the focus of the objective lens to generate an OCT interference signal with the same frequency as that of SS-OCECP. The length of the reference arm was adjusted by 1.40 mm to offset the zero OPD. In both cases, 5000 A-lines were acquired sequentially. Figure 1a, b shows the overlaid interference fringes (n = 5000) from SS-OCECOV and SS-OCECP, respectively. Temporal shifting is much more severe in SS-OCECOV, which implies a better timing stability in SS-OCECP. For the temporal analysis, the timing information of each zero-crossing was obtained through linear interpolation (blue and red dashed boxes in Fig. 1a, b, respectively), and the standard deviation of the timing variation corresponds to the phase stability of the system. For SS-OCECOV, the standard deviation was calculated to be 940 ps, whereas that of SS-OCECP was 35 ps. The corresponding histograms are shown in Fig. 1c. In addition, the phase stabilities of SS-OCECOV and SS-OCECP, which were 175 mrad (~13-nm displacement) and 4.2 mrad (~0.3-nm displacement), respectively, were determined by calculating the standard deviation of the phase angle at the peak in the frequency domain, demonstrating a >40-fold phase stability improvement in SS-OCECP compared to SS-OCECOV.

Enhanced SNR

Since the 3-mm wedged window generates two OCT images in different frequency domains, these two OCT images can be averaged to enhance the SNR, further improving the phase stability. Figure 2a shows the OCT images of the phantom obtained via SS-OCECP; the top and bottom images are the interference signals generated by the back-reflected light from the back and front window surfaces, respectively, with the backscattered light from the phantom. The high-intensity horizontal line between the two OCT images is the interference signal from the two surfaces of the window. The two images are separated by ~3.4 mm. By averaging the two images, the SNR was improved from 73 and 71 to 76 dB, an approximately 3-dB improvement (Fig. 2b). The enhanced SNR through averaging is also reflected on the Doppler OCT images. Figure 2c shows the pair of Doppler images obtained via SS-OCECP, and Fig. 2d shows the averaged result, demonstrating the reduced noise floor and hence improved SNR.

Phantom experiment

After demonstrating the improved SNR and phase stability of the SS-OCECP system, the elastograms of the phantom obtained using both SS-OCECOV and SS-OCECP were compared. The time-lapse Doppler images of SS-OCECOV and SS-OCECP are shown in Fig. 3a–d and Fig. 3e–h, respectively. While an outward propagation of the spherical elastic waves was observed in both cases, the SS-OCECP result reveals a more pronounced boundary between the upward (yellow) and downward (blue) displacement, denoted by the white * in Fig. 3. In addition, this displacement boundary is better maintained in the deeper region when imaged using SS-OCECP (same white * in Fig. 3b, f). Since the deeper region of the image is encoded in the higher-frequency components of the interference signal, a higher phase stability is necessary to reveal the detailed information in those regions. This is further exemplified by the less-phase-stable SS-OCECOV, in which the displacement boundary is more difficult to demarcate (Fig. 3a–d). Figure 3i, j shows the spatiotemporal images from SS-OCECOV and SS-OCECP at the depths indicated by the white arrows in Fig. 3a, e, respectively. The significantly reduced noise floor can be visualized in the SS-OCECP image (Fig. 3j). The propagation speed of the elasticity wave and Young’s modulus of the phantom are shown in Fig. S1.

In vivo rabbit experiment

We further verified the performance of the proposed SS-OCECP in a rabbit model. Figure 4a–d and Fig. 4e–h show the time-lapse Doppler OCT B-scans of rabbit cornea obtained using SS-OCECOV and SS-OCECP, respectively. In these figures, an elastic wave that propagates outwards from the center can be visualized. Figure 4i, j shows the corresponding spatiotemporal images and propagation speeds of two OCE systems at the depths indicated by the white arrows in Fig. 4a, e. The propagation speed of the elasticity wave and Young’s modulus of the cornea are shown in Fig. S1. The results concur with the phantom experiment, demonstrating the enhanced phase stability of SS-OCECP, which allows for a more pronounced displacement boundary, an improved SNR in the deeper region, and reduced background noise.

A highly phase-stable OCE system can detect smaller displacements with improved accuracy. To investigate the influence of the generated ARF amplitude on the phase information retrieval, we applied three different levels of ARF, from 800 to 400 mV, using the same rabbit cornea model (Fig. 5). In all cases, SS-OCECP provided a better visualization of elastic wave propagation than did SS-OCECOV. In the 800-mV SS-OCECOV case, the phase error can be observed at 0.12 ms in Fig. 5a. When applying 600-mV ARF to SS-OCECOV, although bidirectional wave propagation can be identified in the center at 0 ms (Fig. 5d), only one direction of displacement was observed at 0.04 ms (Fig. 5c). A moderately poorer SNR was also observed in the 400-mV SS-OCECOV (Figs. 5e versus f). The corresponding spatiotemporal Doppler OCT images are shown in Fig. 6.

Last, we tested the change in elastic wave velocity in rabbit corneas in vivo with normal and high intraocular pressure (IOP) to further verify the capability of SS-OCECP. A positive correlation between corneal elasticity and IOP was previously reported, and our results (Supplementary Material, Figs S2 and S3), demonstrating the same correlation, agree well with those of the previous study37.

Discussion

OCE benefits from OCT, providing the ability to measure biological tissue with micrometer spatial resolution and subnanometre displacement sensitivity. The static operation principle of SD-OCT contributes to its wide use in OCE. However, recent advancements in SS-OCT have proven its utility in OCE, especially with the advantages of enhanced imaging range, depth, and speed, increased SNR, and reduced phase washout. The phase stability of SS-OCT can be improved through optical and electrical optimization, but reducing the phase fluctuation in a conventional SS-OCT setup is fundamentally challenging, as the reference and sample signals travel through different optical paths. We have previously demonstrated a method to optimize the electrical components in an SS-OCT system to achieve high-phase stability38, and in this study, we employed a common-path configuration to further attain the peak performance of SS-OCE. This was accomplished by enhancing the SNR through averaging, minimizing the timing jitter by adjusting the electrical delay, and reducing the fluctuation of the OPD via the common-path configuration. The resulting SS-OCECP demonstrated a phase stability of 4.2 mrad, which was not only obtained in the system characterization but also achieved during the experiments. In addition to the 40-fold improvement in the phase stability compared to that of SS-OCECOV, SS-OCECP showed a 3-dB improvement in the imaging SNR, all without the need for external stabilization or extravagant post-processing.

The phase performance of our SS-OCECP was first validated using a tissue-mimicking silicone phantom. The improved phase stability was reflected by the more pronounced displacement boundary of the elastic wave than that of SS-OCECOV. We repeated the experiment using an in vivo rabbit corneal model to further demonstrate the improved capability of SS-OCECP to retrieve precise phase information for elasticity quantification. The results of the IOP experiment are also supported by reported studies37. Additionally, the improved displacement sensitivity provided by SS-OCECP can reduce the minimum ARF required to induce a detectable tissue displacement, which is essential for future clinical translation.

Although we have demonstrated the superior performance of SS-OCECP, there are a few design improvements that can be implemented. First, in the proposed optical configuration, the reference signals are generated by the front and back surfaces of the 3-mm wedged window. To achieve the optimal SNR, the travel distance of the detection beam from the scan lens to the first surface of the window must be constant to provide a uniform back-reflected signal; even a slight deviation will cause a variation in the OPD and back-reflected power during scanning, resulting in a reduced SNR. For applications that require scanning of a larger area, a scan lens that provides a larger field of view should be used. Furthermore, for three-dimensional OCE, a 4 F optical corrector can be incorporated into the scanning design to ensure a constant entrance pupil and OPD.

In addition, we previously demonstrated a confocal alignment between the OCT detection beam and the excitation via a coaxial configuration for high excitation efficiency15,32. A confocal/coaxial setup can improve the ease of use and reduce the form factor of the sample arm, further facilitating the translation of this technology to clinical use. In our current SS-OCECP design, the wedged window prevents this confocal setup, as the ARF will be attenuated by the window. Alternatively, the wedged window can be fabricated using an optically and acoustically transparent material, such as Pebax® and low-density polyethylene39,40. With this window, a ring-shaped ultrasound transducer can be inserted between the scan lens and the window for excitation, allowing the OCT detection beam to travel through the center of the transducer for imaging.

Finally, the light source of the SS-OCECP is a vertical-cavity surface-emitting laser with an internal MZI that provides a k-clock signal at ~400 MHz, allowing for an imaging range of ~11 mm in standard OCT or ~5.5 mm when utilizing the proposed averaging method that enhances the SNR by 3 dB. While a 5.5-mm imaging range may be sufficient in many applications, a long imaging range can be achieved through doubling the k-clock frequency by building an external circuit or through the dual edge sampling provided by certain waveform digitizers. A custom-built external k-clock can also be considered. Alternatively, an acousto-optic modulator can be incorporated to shift the frequency of the interferometer signal to take advantage of the full bandwidth of the frequency41. With respect to achieving a better penetration depth, swept-source lasers with a longer center wavelength, such as 1.7 μm, can be utilized42.

In summary, we have reported the first OCE system based on SS-OCT with a common-path configuration. A phase stability of 4.2 mrad was obtained, and the feasibility and performance of our SS-OCECP were tested and validated using a phantom and in vivo rabbit model. This highly phase-stable system can quantify displacement in the subnanometre range, and we believe that it has great potential in other applications that require precision phase measurement, such as flowmetry11, vibrometry43, and molecular imaging44.

Materials and methods

System setup

An SS-OCECP system was designed and constructed. The swept laser (SL1310V1-10048, Thorlabs, Inc., NJ) has a repetition rate of 100 kHz, a center wavelength of 1310 nm, and a bandwidth of 100 nm. The system has an imaging range of 11 mm, which makes the generation of two OCT images in different frequency domains possible. The output light from the laser source is split by a 90:10 optical fiber coupler, with 90% of the light propagating to the sample through a circulator, a collimator, an objective scan lens (LSM04, Thorlabs, Inc., NJ), and a wedged window, as shown in Fig. 7. The common-path configuration is achieved through the 30-arcmin wedged window. In contrast to a flat window, the 30-arcmin angle on the front surface effectively reduces the autocorrelation fringe patterns generated within the window cavity, as shown in Fig. 8. In this setup, two interfaces exist: the air-glass front surface and the glass-gel back surface. The indices of refraction of the air, glass (the wedged window), and ultrasound gel are 1.0, 1.5, and 1.34, respectively. The back surface of the wedged window is perpendicular to the OCT scanning beam, while the front surface is shifted by 30 arcmin from the normal direction. The differences in the refractive indices and in the corresponding incident angles contribute to the discrepancy in reflectance of the two surfaces, but this can be compensated for by adjusting the position of the wedged window relative to the scan lens because the collected power of the focusing back-reflected light is spatially dependent (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4). As such, two back-reflected reference signals of similar power interfere with the backscattered sample signal to generate two distinct fringes corresponding to the top and bottom images. The two interferences are then delivered to one channel of the balanced photodetector. The wedged window has a thickness of 3 mm, which corresponds to a 3.4-mm axial separation of the generated OCT images calculated based on the ultrasound gel reflective index of 1.34. Additionally, the two images can be averaged to enhance the SNR and minimize speckles. To enable balanced detection, the remaining 10% of the light propagates through a compensation arm consisting of a circulator, a collimator, an adjustable slit and a mirror. The back-reflected light from the compensation arm is detected by the second channel of the balanced photodetector to offset the DC component of the generated interference fringes. A balanced photodetector with a bandwidth from 30 kHz to 1.6 GHz was selected to minimize timing jitters to enhance the phase stability and to enable a long imaging range for retrieving the two OCT interference fringes from different frequency domains14.

For the displacement excitation, a custom-built 4.5-MHz ultrasound transducer with a focal length of 35 mm is placed approximately orthogonal to the scan lens. A function generator is synchronized with the λ-trigger signal to generate a 4.5-MHz sine wave (duration: 200 μs) that is then amplified by approximately 42 dB to drive the ultrasound transducer for tissue excitation. The space between the wedged window, the ultrasound, and the sample is filled with ultrasound gel to couple the ARF.

For comparison, SS-OCECP can be quickly converted to SS-OCECOV during the experiments while maintaining the exact location of the sample and the ultrasound transducer relative to the OCT detection beam (Supplementary Material, Fig. S5).

Data acquisition, synchronization, and signal processing

Two timing signals produced by the swept-source laser are utilized for data acquisition and synchronization. The k-clock signal generated by the internal MZI provides a timing of equal wavenumber spacings, and the λ-trigger signal is produced by the internal FBG to give a temporal mark for each wavelength sweeping. In conventional SS-OCT or SS-OCE imaging systems, a series of OCT signal points is digitized starting at the edge of the λ-trigger, while the signal digitization is clocked by the k-clock signal for k-linear signal sampling. However, in this mode of operation, random timing errors of the signal edges can be magnified to significant timing fluctuations between the k-clock and λ-trigger through a process termed edge collision38. To achieve the best stability, the signal delays are adjusted to the optimal values for the k-clock, λ-trigger and OCE signals. A previous study on the phase stability with the same type of swept lasers suggested that a very high stability could be obtained using this method38.

The propagation velocity of the elastic wave provides a direct measurement of the biomechanical property, as pre-calibration is not necessary to convert the displacement to elasticity. To visualize the elastic wave propagation, an M-B scanning protocol is utilized to induce and detect the displacement. At each lateral position, 500 A-lines are acquired to record the phase change over time (M-mode). The ultrasound transducer is excited after a trigger delay of 1 ms to generate an ARF with a duration of 200 μs for each M-mode acquisition. After one M-mode acquisition, the galvanometer scanner moves the detection beam to the next lateral position, and the same step is repeated. A total of 3000 M-mode images are acquired for each dataset to convert to B-mode images. The scanning protocol is summarized in Fig. S6 in the Supplementary Material. The phase-resolved Doppler algorithm is applied to extract the temporal phase information. With a time interval of 50 μs, inter-A-line analysis is performed to obtain time-lapse Doppler OCT B-scans and spatiotemporal Doppler OCT images. Young’s modulus can then be calculated by determining the propagation velocity using the spatiotemporal Doppler images. Because the different boundary conditions yield different propagation modes of the elastic waves, a specific equation is used to calculate the elasticity based on the sample types8,45. In our experiment, Young’s modulus, E, is calculated based on the Rayleigh wave velocity, VR, and Lamb wave velocity, VL, for the tissue-mimicking phantom and rabbit cornea, respectively. The data processing steps and key equations for elasticity calculation are detailed in Fig. S7 in the Supplementary Material.

Phantom preparation

To fabricate the silicone-based phantom that mimics tissue biomechanical properties, 2 g of titanium dioxide was added to every 100 g of silicone rubber base (P4—Part B, Eager Polymers, Inc., IL) and mixed using an ultrasonic cleaner. Then, 1 part of the silicone rubber base with well-mixed titanium dioxide was added to 16 parts of silicone activator (P4—Part A, Eager Polymers, Inc., IL). After the base was gently mixed with the activator using a stirring rod, the mixture was placed into a vacuum chamber until all the air bubbles trapped inside the mixture were removed. The mixture was then poured into a container for molding and cured for 24 h. The final phantom had dimensions of 40 mm × 40 mm × 10 mm.

In vivo rabbit experiment preparation

To induce the initial anesthesia, the rabbit (New Zealand white rabbit, male, ~3 kg) was administered a ketamine-xylazine mixture (35 mg/kg and 5 mg/kg, respectively) subcutaneously. Two drops of 2.5% proparacaine hydrochloride were applied topically for local anesthesia. After conforming to the proper depth of anesthesia, the rabbit was placed onto a stage for position adjustment. The rabbit’s eye was covered with sterile ultrasound gel to provide a conductive medium between the eye and the acoustic wave for the IOP experiment. To obtain a higher IOP, the rabbit eye was carefully proptosed, and a sterile latex drape with an aperture was put through the globe to maintain proptosis. Eye proptosis in rabbits typically increases the IOP to ~50 mmHg. All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of California, Irvine, under protocol #AUP-19-042.

References

Schmitt, J. M. OCT elastography: imaging microscopic deformation and strain of tissue. Opt. Express 3, 199–211 (1998).

Kennedy, B. F., Wijesinghe, P. & Sampson, D. D. The emergence of optical elastography in biomedicine. Nat. Photonics 11, 215–221 (2017).

Feng, Y. et al. Viscoelastic properties of the ferret brain measured in vivo at multiple frequencies by magnetic resonance elastography. J. Biomech. 46, 863–870 (2013).

Zhang, X. Y. et al. Noninvasive assessment of age-related stiffness of crystalline lenses in a rabbit model using ultrasound elastography. Biomed. Eng. OnLine 17, 75 (2018).

Yun, S. H. & Chernyak, D. Brillouin microscopy: assessing ocular tissue biomechanics. Curr. Opin. Ophthalmol. 29, 299–305 (2018).

Muthupillai, R. & Ehman, R. L. Magnetic resonance elastography. Nat. Med. 2, 601–603 (1996).

Qu, Y. Q. et al. Acoustic radiation force optical coherence elastography of corneal tissue. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 22, 6803507 (2016).

Kirby, M. A. et al. Optical coherence elastography in ophthalmology. J. Biomed. Opt. 22, 121720 (2017).

Qu, Y. Q. et al. Miniature probe for mapping mechanical properties of vascular lesions using acoustic radiation force optical coherence elastography. Sci. Rep. 7, 4731 (2017).

Song, S. Z. et al. Strategies to improve phase-stability of ultrafast swept source optical coherence tomography for single shot imaging of transient mechanical waves at 16 kHz frame rate. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 191104 (2016).

Zhao, Y. H. et al. Phase-resolved optical coherence tomography and optical Doppler tomography for imaging blood flow in human skin with fast scanning speed and high velocity sensitivity. Opt. Lett. 25, 114–116 (2000).

Szkulmowska, A. et al. Phase-resolved Doppler optical coherence tomography-limitations and improvements. Opt. Lett. 33, 1425–1427 (2008).

Qu, Y. Q. et al. In vivo elasticity mapping of posterior ocular layers using acoustic radiation force optical coherence elastography. Investigative Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 59, 455–461 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Simultaneously imaging and quantifying in vivo mechanical properties of crystalline lens and cornea using optical coherence elastography with acoustic radiation force excitation. APL Photonics 4, 106104 (2019).

He, Y. M. et al. Confocal shear wave acoustic radiation force optical coherence elastography for imaging and quantification of the in vivo posterior eye. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 25, 7200107 (2019).

Kang, J. U. et al. Common-path optical coherence tomography for biomedical imaging and sensing. J. Optical Soc. Korea 14, 1–13 (2010).

Vakhtin, A. B. et al. Common-path interferometer for frequency-domain optical coherence tomography. Appl. Opt. 42, 6953–6958 (2003).

Tan, K. M. et al. In-fiber common-path optical coherence tomography using a conical-tip fiber. Opt. Express 17, 2375–2384 (2009).

Lan, G. P. et al. Common-path phase-sensitive optical coherence tomography provides enhanced phase stability and detection sensitivity for dynamic elastography. Biomed. Opt. Express 8, 5253–5266 (2017).

Leartprapun, N. et al. Photonic force optical coherence elastography for three-dimensional mechanical microscopy. Nat. Commun. 9, 2079 (2018).

Ahmad, A. et al. Magnetomotive optical coherence elastography using magnetic particles to induce mechanical waves. Biomed. Opt. Express 5, 2349–2361 (2014).

Zhang, H. Q. et al. Optical coherence elastography of cold cataract in porcine lens. J. Biomed. Opt. 24, 036004 (2019).

Qu, Y. Q. et al. Quantified elasticity mapping of retinal layers using synchronized acoustic radiation force optical coherence elastography. Biomed. Opt. Express 9, 4054–4063 (2018).

He, Y. M. et al. Characterization of oviduct ciliary beat frequency using real time phase resolved Doppler spectrally encoded interferometric microscopy. Biomed. Opt. Express 10, 5650–5659 (2019).

Hendargo, H. C. et al. Doppler velocity detection limitations in spectrometer-based versus swept-source optical coherence tomography. Biomed. Opt. Express 2, 2175–2188 (2011).

De Boer, J. F., Leitgeb, R. & Wojtkowski, M. Twenty-five years of optical coherence tomography: the paradigm shift in sensitivity and speed provided by Fourier domain OCT [Invited]. Biomed. Opt. Express 8, 3248–3280 (2017).

Song, S. Z., Xu, J. J. & Wang, R. K. Long-range and wide field of view optical coherence tomography for in vivo 3D imaging of large volume object based on akinetic programmable swept source. Biomed. Opt. Express 7, 4734–4748 (2016).

Tsai, M. T. et al. Quantitative phase imaging with swept-source optical coherence tomography for optical measurement of nanostructures. IEEE Photonics Technol. Lett. 24, 640–642 (2012).

De Stefano, V. S. et al. Live human assessment of depth-dependent corneal displacements with swept-source optical coherence elastography. PLoS ONE 13, e0209480 (2018).

Razani, M. et al. Feasibility of optical coherence elastography measurements of shear wave propagation in homogeneous tissue equivalent phantoms. Biomed. Opt. Express 3, 972–980 (2012).

Manapuram, R. K. et al. In vivo estimation of elastic wave parameters using phase-stabilized swept source optical coherence elastography. J. Biomed. Opt. 17, 100501 (2012).

Zhu, J. et al. Coaxial excitation longitudinal shear wave measurement for quantitative elasticity assessment using phase-resolved optical coherence elastography. Opt. Lett. 43, 2388–2391 (2018).

Singh, M. et al. Evaluating the effects of Riboflavin/UV-A and Rose-Bengal/Green light cross-linking of the rabbit cornea by noncontact optical coherence elastography. Investigative Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 57, OCT112–OCT120 (2016).

Zhu, J. et al. Imaging and characterizing shear wave and shear modulus under orthogonal acoustic radiation force excitation using OCT doppler variance method. Opt. Lett. 40, 2099–2102 (2015).

Zhi, Z. W. et al. 4D optical coherence tomography-based micro-angiography achieved by 1.6-MHz FDML swept source. Opt. Lett. 40, 1779–1782 (2015).

Zhang, J. et al. High-dynamic-range quantitative phase imaging with spectral domain phase microscopy. Opt. Lett. 34, 3442–3444 (2009).

Ambroziński, Ł. et al. Acoustic micro-tapping for non-contact 4D imaging of tissue elasticity. Sci. Rep. 6, 38967 (2016).

Moon, S. & Chen, Z. P. Phase-stability optimization of swept-source optical coherence tomography. Biomed. Opt. Express 9, 5280–5295 (2018).

Yang, J. M. et al. Photoacoustic endoscopy. Opt. Lett. 34, 1591–1593 (2009).

Li, Y. et al. PMN-PT/Epoxy 1-3 composite based ultrasonic transducer for dual-modality photoacoustic and ultrasound endoscopy. Photoacoustics 15, 100138 (2019).

Jing, J. et al. High-speed upper-airway imaging using full-range optical coherence tomography. J. Biomed. Opt. 17, 110507 (2012).

Li, Y. et al. Intravascular optical coherence tomography for characterization of atherosclerosis with a 1.7 micron swept-source laser. Sci. Rep. 7, 14525 (2017).

Choi, S. et al. Multifrequency-swept optical coherence microscopy for highspeed full-field tomographic vibrometry in biological tissues. Biomed. Opt. Express 8, 608–621 (2017).

Makita, S. & Yasuno, Y. Detection of local tissue alteration during retinal laser photocoagulation of ex vivo porcine eyes using phase-resolved optical coherence tomography. Biomed. Opt. Express 8, 3067–3080 (2017).

Zhu, J., He, X. D. & Chen, Z. P. Perspective: current challenges and solutions of Doppler optical coherence tomography and angiography for neuroimaging. APL Photonics 3, 120902 (2018).

Acknowledgements

National Institutes of Health (R01EY-026091, R01EY-028662, R01HL-125084, R01HL-127271), American Heart Association (18PRE34050021), and the National Science Foundation (DGE-1839285).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Y. conceived the idea, designed the system setup, conducted the animal experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. M.S. analyzed the data and edited the manuscript. C.J. edited the manuscript and conducted the animal experiments. Z.Z. drew the system diagrams. C.Z. conceived the idea, supervised the research, and edited the manuscript. All authors discussed and contributed to the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Chen has a financial interest in OCT Medical Imaging, Inc., which, however, did not support this work.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Moon, S., Chen, J.J. et al. Ultrahigh-sensitive optical coherence elastography. Light Sci Appl 9, 58 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-020-0297-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41377-020-0297-9

This article is cited by

-

Brillouin microscopy

Nature Reviews Methods Primers (2024)

-

High speed photo-mediated ultrasound therapy integrated with OCTA

Scientific Reports (2022)