Abstract

Deficiency of the transcription factor GATA2 is a highly penetrant genetic disorder predisposing to myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and immunodeficiency. It has been recognized as the most common cause underlying primary MDS in children. Triggered by the discovery of a recurrent synonymous GATA2 variant, we systematically investigated 911 patients with phenotype of pediatric MDS or cellular deficiencies for the presence of synonymous alterations in GATA2. In total, we identified nine individuals with five heterozygous synonymous mutations: c.351C>G, p.T117T (N = 4); c.649C>T, p.L217L; c.981G>A, p.G327G; c.1023C>T, p.A341A; and c.1416G>A, p.P472P (N = 2). They accounted for 8.2% (9/110) of cases with GATA2 deficiency in our cohort and resulted in selective loss of mutant RNA. While for the hotspot mutation (c.351C>G) a splicing error leading to RNA and protein reduction was identified, severe, likely late stage RNA loss without splicing disruption was found for other mutations. Finally, the synonymous mutations did not alter protein function or stability. In summary, synonymous GATA2 substitutions are a new common cause of GATA2 deficiency. These findings have broad implications for genetic counseling and pathogenic variant discovery in Mendelian disorders.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

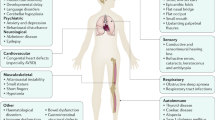

Germline mutations in the GATA2 gene, mostly arising de novo, had been reported to cause an immunodeficiency/myelodysplasia syndrome manifesting with a multitude of clinical phenotypes. These include monocytopenia and mycobacterial infections syndrome (MonoMAC syndrome) [1], dendritic cell, monocyte, B and NK lymphoid deficiency (DCML deficiency) [2], familial myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS)/acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [3], chronic neutropenia [4], Emberger syndrome [5] and warts, immunodeficiency, lymphedema and anogenital dysplasia syndrome (WILD syndrome) [6]. Finally, GATA2 deficiency is considered the most common hereditary predisposition to pediatric MDS, accounting for as much as 15% of MDS with excess of blasts (MDS-EB), with a particularly high prevalence among MDS patients carrying monosomy 7 (37%) [7]. To date, more than 400 GATA2-deficient cases have been published [8, 9] with three major types of pathogenic GATA2 mutations: (1) missense mutations within zinc finger 2 (ZnF2), (2) null mutations (splice site, nonsense, frameshift, and whole gene deletions), and (3) noncoding substitutions in the EBOX-GATA-ETS regulatory region in intron 4 (hg19, g.128202128-128202173, NM_032638.4) [8,9,10]. Overall, germline GATA2 mutations are thought to result in haploinsufficiency and context-dependent loss of essential transcription factor activity [3, 5, 11,12,13,14].

Genomic studies typically focus on the discovery of nonsynonymous variants that alter coding regions or canonical splice sites because their effect is predictable. Conversely, due to codon degeneracy, synonymous substitutions do not alter the amino acid composition of the encoded protein and are usually not reported as pathogenic. However, previous studies revealed that such variants can alter RNA or protein on multiple levels including pre-mRNA splicing, messenger RNA (mRNA) stability and structure, miRNA binding, and translation [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24].

Here, we initially identified a synonymous substitution in exon 3 of the GATA2 gene (c.351C>G, p.T117T) in two unrelated pedigrees, with the clinical phenotype of GATA2 deficiency. The variant was recently reported in an adult patient (the mother of two siblings studied here) presenting with immunodeficiency, severe infections and lung disease [25]. This prompted us to study the contribution of synonymous alterations to the genetic spectrum of GATA2 deficiency and to assess their pathogenic role. We discovered and characterized five distinct synonymous mutations with RNA-deleterious effect in nine patients. They represent a new type of mutation in GATA2 deficiency and have broad implications for both the discovery of disease-causing mutations and genetic counseling.

Methods

Patient cohort and genomics

The screening cohort consisted of 911 patients (Fig. 1a): 729 children and adolescents with primary MDS classified according to WHO criteria [26,27,28] enrolled in the studies 1998 and 2006 of the European Working Group of MDS in Childhood (EWOG-MDS, #NCT00662090), and 182 patients with cytopenias and/or GATA2-specific clinical problems, referred to our diagnostic laboratory. GATA2 gene sequence, including intron 4 was analyzed in bone marrow (BM) samples using targeted deep sequencing with Sanger sequence validation, and subsequent confirmation of germline mutational status in nonmyeloid tissues as previously reported [7, 29]. Whole exome/genome sequencing (WES/WGS) was performed in patients with synonymous GATA2 variants to rule out other hereditary causes (Supplementary methods, Supplementary Table 1).

a Flow diagram depicts the screening cohort and GATA2 mutations identified. b Overall distribution of genotypes among 110 patients with GATA2 deficiency. Truncating variants are localized prior to or within zinc finger 2; missense mutations cluster mainly to zinc finger 2 region; intron 4 mutations affect the EBOX-GATA-ETS regulatory region (+9.5 kb) of GATA2; other: one in-frame deletion and two whole gene deletions; synonymous variants are proposed as a new group of pathogenic GATA2 mutations. Numbers in parentheses refer to individual patients. c Frequency of patients with synonymous mutations among all GATA2 positive cases and among the group of patients carrying exonic substitutions. d Schematic representation of the GATA2 gene (NM_032638.4) with synonymous variants identified. Affected nucleotide is shaded blue and dashed line boxes indicate respective codon triplet. Nucleotide conservation is presented for nine species. Evolutionary conservation is depicted on the bottom as Genomic Evolutionary Rate Profiling (GERP + + RS) score with values ranging from −12.36 to 6.18, and 6.18 being the most conserved. Splicing prediction was performed with Human Splicing Finder v.3.0. ESS exonic splicing silencer, ESE exonic splicing enhancer.

Targeted investigations of GATA2 transcript expression

We analyzed RNA expression in blood, BM or fibroblasts using Sanger, deep sequencing, and TA cloning-based sequencing (Supplementary methods, Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 2). In addition, GATA2 expression in various hematopoietic compartments of healthy controls was measured (Supplementary methods).

Studies of GATA2 protein stability and function

In order to explore the influence of synonymous mutations on protein stability and function, in vitro analysis of exogenously expressed GATA2 was performed in 293T cells. To further investigate the protein function, in vivo studies in zebrafish were accomplished (for details see Supplementary methods). Experiments were performed in duplicates or triplicates as indicated in the figure legends.

Statistics

For reporter assay, data from biological and technical triplicate experiments were presented as the mean values ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical significance was assessed using GraphPad Prism v 7.04 software employing either standard one-way ANOVA test (reporter assay, thermodynamic effect of GATA2 variants) or Student’s t test (allele quantification in patients’ cDNA by deep sequencing, frequency of zebrafish phenotypes). P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Identification of synonymous GATA2 variants

We initially discovered two unrelated individuals (P1, P3) with GATA2 deficiency carrying an identical synonymous GATA2 variant. This prompted a systematic evaluation of the GATA2 gene sequence in our screening cohort of patients presenting for the most part with the phenotype of pediatric MDS (Fig. 1a). At first, we categorized “classical” disease-causing alterations and identified 101 patients with 62 distinct pathogenic GATA2 mutations (Fig. 1a). The distribution of mutations corroborated data reported in previous studies [9]. The most common were null mutations affecting the N-terminal part of the protein: stop-gain, frameshift, splice site (N = 52), followed by missense mutations within or adjacent to ZnF2 (N = 36), intron 4 EBOX-GATA-ETS site alterations (N = 10), and other aberrations (N = 3): one in-frame and two whole gene deletions (Fig. 1b).

Next, we searched GATA2 coding sequence for the presence of synonymous substitutions. Variants that are either not reported or very rare (<0.05% allele frequency) in the gnomAD population database were found in nine patients. These variants were present in 8.2% (9/110) of all patients with GATA2 alterations, and 14.8% (9/61) of cases with GATA2 exonic substitutions only (Fig. 1c). In comparison, common polymorphisms with synonymous effect p.P5P, p.P22P, p.Q38Q, p.T188T, and p.A411A were not significantly enriched in our cohort (not shown), arguing against their disease-causing role in MDS.

The synonymous substitutions encountered in P1–P9 were predicted to have a likely benign effect using the combined annotation-dependent depletion score (CADD) and gene-specific calibration by Gene-Aware Variant INterpretation (GAVIN) (Table 1). The evolutionary nucleotide conservation was high for c.351 and c.649 nucleotides (Fig. 1d), suggesting their resistance to evolutionary change. Splicing prediction tools assigned a high chance of splice defects to c.351C>G, c.981G>A, and c.1023C>T variants either via activation of a cryptic donor, introduction of an alternative splicing silencer or disruption of an existing splicing enhancer (Fig. 1d, Supplementary Fig. 2, and Table 1).

Phenotype of patients with synonymous GATA2 mutations

Patients with synonymous GATA2 mutations were diagnosed at a median age of 11.5 (3–24) years. Hematologic and immunological phenotypes were consistent with the heterogeneous clinical picture of GATA2 deficiency and included varying degrees of immune cytopenias (low B/NK, DC cells, monocytopenia), immunodeficiency, neutropenia, and/or pancytopenia (supplemental case descriptions). P2 is the sibling of GATA2-deficient patient P1 and was categorized as a silent GATA2 mutation carrier with a reduction of B- and NK-cells. Their mother was previously reported with pulmonary alveolar proteinosis [25]. P7 and P8 (unrelated, carrying the same mutation), initially presented with thrombocytopenia and while P8 developed transfusion-dependent refractory cytopenia of childhood (RCC), P7 remained stable with BM morphology suspicious for RCC. P9 was first seen with complications of immunodeficiency and clinically evolved to MDS. Monosomy 7 in BM was detected at diagnosis in four patients (P1, P3, P4, and P6), normal karyotypes were present in four (P5, P7, P8, and P9), while no marrow exam was performed in P2 (Table 2). According to the WHO classification, P1 and P4–P8 were diagnosed with RCC, and P9 with MDS with multilineage dysplasia as a young adult. Initial disease of P3 was MDS-EB, which progressed to AML after 6 months. Other clinical problems in the affected patients were transient organ dysfunction after birth and facial abnormalities in P4, hepatosplenomegaly in P5, hypospadias in P6, and Crohn’s colitis as well as HPV-driven neoplasia in P9. The majority of patients (6/9) underwent allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) with favorable outcome: 5/6 patients were alive at last follow up (at a median of 1.9 years after HSCT) and 1/6 (P3) died from infection 7 months following HSCT (Table 2).

Exclusion of other hereditary causes

We next aimed to determine if other genetic conditions predisposing to inherited bone marrow failure (IBMF) or MDS might have been previously missed in our patients. WES/WGS was performed in all families with exception of P8 who was assessed by a 135 IBMFS/MDS gene panel. The WES analysis focused on known IBMF/MDS and pancancer genes (300 genes) [26, 30]. Multiple heterozygous variants of uncertain significance (VUS) were identified (Supplementary Table 1). After comprehensive review by a multidisciplinary board representing pediatric hematology, genetic counseling, and molecular biology, only P6 remained with additional potentially pathogenic SAMD9 variants p.K877E and p.F366LfsX33. This patient did not have features typical for MIRAGE syndrome, which was initially ascribed to SAMD9 mutations [31, 32]. Notably, we discovered VUS in the Fanconi anemia (FA) genes FANCD1, FANCD2, and FANCS in three patients. However, these VUS were heterozygous and FA was ruled out in all three patients by means of chromosomal breakage studies and clinical phenotyping.

Synonymous GATA2 variants result in selective loss of mRNA expression

Building on the assumption that synonymous variants detected in our patients were associated with degradation of the mutant (Mut) mature mRNA, we first sequenced cDNA transcribed from polyadenylated RNA transcripts (equivalent to mRNA) using Sanger method. Compared with genomic DNA, cDNA sequences showed loss of heterozygosity manifested by complete lack of the Mut allele in five out of seven cases: P1, P3, P5, P6, and P7, and a substantial reduction in P4 and P9 (Fig. 2a upper panel). Compared with hematopoietic specimens, Mut allele expression was slightly higher in skin fibroblasts of P1 and P4 (Fig. 2a lower panel). Because it is not known if monoallelic GATA2 expression might be a general phenomenon in normal hematopoiesis, we sequenced three healthy controls who carried a common heterozygous polymorphism (rs2335052: c.490G>A; p.A164T). Both the genomic DNA and cDNA showed an equal ratio of alternative to reference alleles (Fig. 2b).

a Upper panel: Representative electropherograms with genomic and cDNA sequence surrounding the affected nucleotide (red line). All five distinct synonymous mutations are represented. Lower panel: Comparison of allelic expression in the hematopoietic and nonhematopoietic tissue of P1 and P4. b Genetic testing of healthy controls carrying a common nonsynonymous GATA2 polymorphism c.490G>A (19.5% minor allele frequency in gnomAD). c Allelic frequency of GATA2 alleles determined by targeted deep sequencing of patients’ cDNA; numbers of reads taken from one representative replicate. In all cases oligo(dT) priming was used with exception of P4 and P5 (*) where the mixture of random hexamers and oligo(dT) was utilized. Outside right: Boxplot depicts combined allelic contribution in all patients. Calculation of p value was performed using Student’s t test (mean ± SD values). d Frequency of mutated alleles determined by deep sequencing of cDNA obtained from bone marrow RNA using two different reverse transcription priming methods. Mutant vs. total read counts are shown in parentheses, and percentage represents the proportion of mutated alleles in the sample. BM bone marrow, Fib fibroblasts, PB peripheral blood.

Deep sequencing based quantification of allelic frequency showed nearly total absence of Mut alleles in P1, P3, P5–P7, and a reduction of Mut expression to 21% in P4 (Table 1 and Fig. 2c). Combined across all samples, we observed median values of 27 reads for Mut, versus 330,544 reads for wild-type (WT) alleles. Lastly, TA cloning of P5’s and P6’s cDNA followed by sequencing of an average of 345 single colonies was a third independent method confirming the RNA reduction (0% and 11% of Mut amplicons for P5 and P6, respectively, not shown). In order to address at which stage of RNA maturation the Mut alleles were lost, we deep sequenced products that were reverse-transcribed using alternative priming approaches. While oligo(dT) that are specific to mature transcripts (mRNA) produced almost exclusively GATA2 WT reads, the use of random hexamers (enriching both pre-mRNA and mRNA) resulted in an increase of Mut reads to ~30% for P1 and P6 (Fig. 2d).

Splicing analysis of the GATA2 gene

In order to ascertain the mechanism of monoallelic GATA2 expression, RNA sequencing (RNAseq) was performed in sorted CD34+ BM cells of five patients (P1, P4–P7). Isoform analysis revealed two novel splice junctions in P1, not observed in the Ensembl database and healthy controls (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 3). In both new transcripts in P1 the c.351C>G mutation acts as a new splice donor that joins to alternative acceptors either at c.488 or at c.608. Long range RT-PCR and sequencing in P1′ BM and fibroblasts (Fig. 3b) confirmed the presence of the transcript with c.488 alternative acceptor. Finally, TA cloning of the cDNA PCR products of P1 and sequencing of 348 colonies revealed the presence of three novel transcripts (Fig. 3c). Two of these were identical as detected by RNAseq; the third transcript found in only nine colonies harbors the c.351 donor that joins to a new splice acceptor at position c.539. All three transcripts resulted in sequence frameshift and occurrence of a premature stop codon at c.650. No new isoforms were found in P4–P7 by RNAseq; additional TA cloning and sequencing of cDNA in P5 and P6 detected only properly spliced full length transcripts.

a Sashimi plot of GATA2 exon 3 of P1 depicting two novel splicing events (represented by arcs) detected by RNAseq; dashed lines indicate the positions of an alternative donor and two new acceptors. b Long range RT-PCR spanning exon 2–5 of GATA2 transcript revealed the presence of an additional shorter product of 860 bp in P1 (indicated by asterisk (*)) corresponding to one of the transcripts found by RNAseq (donor: c.351—acceptor: c.488). Only wild-type allele (996 bp) was detected in P3–P6. c Frequency and schematic representation of novel splicing patterns in P1 detected by TA cloning of the RT-PCR product. It confirmed the presence of three novel transcripts, of which two were also identified by RNAseq. BM bone marrow, Fib fibroblasts, PB peripheral blood. GATA2 (NM_032638.4).

Synonymous variants are predicted not to affect RNA stability

The impact of synonymous variants on mRNA stability and secondary structure was determined using Mfold, RNAfold, and Quickfold tools. Synonymous substitutions were predicted not to significantly affect secondary structure of mRNA (Supplementary Fig. 4a). In addition, no relevant energy change (ΔG) was observed between Mut and WT (Supplementary Fig. 4b). As a comparison, five common synonymous polymorphisms from GnomAD and five nonsynonymous pathogenic GATA2 mutations were included in the analysis. None of these variants had influence on the mRNA structure and thermodynamic characteristics.

Analysis of protein stability and function

We investigated the levels of endogenous GATA2 protein in P9 who carried RNA-deleterious mutation c.351C>G, p.T117T and had sufficient primary specimen. Analysis was performed in patient-derived platelets since GATA2 was previously found to be highly expressed in this hematopoietic subpopulation (Supplementary Fig. 5) [33, 34].

GATA2 protein levels were severely reduced, similarly to other known pathogenic GATA2 mutations (Fig. 4a). Next, to determine the effect of the synonymous variants on GATA2 transcriptional function, GATA-specific reporter assay was performed. Transactivation activity was comparable between synonymous Mut and WT (Fig. 4b). We subsequently assessed the protein:DNA-binding ability using the electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) for the mutation c.649C>T, p.L217L. Using this limited approach, no significant difference in DNA binding between Mut and WT GATA2 proteins was seen (Fig. 4c). Of note, both functional experiments were performed at steady state with a high level of ectopic protein expression.

a Expression of endogenous GATA2 protein in platelets of P9 (c.351C>G, p.T117T). Left: Representative western blot image for the expression level of GATA2 and ß-actin. Right: Relative optical density of GATA2 protein normalized with ß-actin. GATA2 deficiency group comprises four pathogenic mutations in GATA2 coding region. b Transactivation activity measured by GATA reporter assay. Previously reported p.L359V mutant was used as a positive control. Fold activation of luciferase reporter was determined from the triplicate values from three independent experiments and presented as the mean ± SD values. Comparison between the GATA2 WT and each synonymous Mut, as well as p value calculation was performed using a standard one-way ANOVA test. c The electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) depicting DNA-binding ability of GATA2 p.L217L, compared with WT and a known loss-of-function mutation p.R396Q, lanes spliced from the same gel runs (experiment repeated three times). Shift: semiquantitative comparison of GATA2 binding strength to the target oligo (biotin-labeled probe containing wild-type target sequence); Super Shift: specificity of FLAG-GATA2 binding to DNA sequence with anti-FLAG antibody (Ab); Competition: includes 10× and 100× excess of unlabeled wild-type probe competing for binding of the protein; Specificity: contains biotin-labeled probe with mutated target sequence which cannot be bound by the analyzed protein. Three latter setups verify that the signal obtained in the shift reaction is the result of specific DNA-protein interaction. d Assessment of translation efficiency (left) and protein stability (right) of GATA2 synonymous mutants in transiently transfected 293T cells treated with 1 µg/ml actinomycin D and 10 µg/ml cycloheximide, respectively. Experiments were performed in duplicates. Blots from representative experiments are shown.

Because it is known that synonymous variants can impair translation, we aimed to analyze the effect of Muts on protein levels. We ectopically expressed cDNA under the principle that splicing effect will not be expected due to missing introns, and observed protein changes will result from altered translation. We blocked the transcription with actinomycin D in transfected 293T cells and analyzed protein levels over time (Fig. 4d). Expectedly, protein content decreased during the course of treatment for all genotypes resulting from exhaustion of mRNA reserves. However, p.L217L showed slightly higher protein content as compared with WT. To better delineate the cause for the relative increase in protein levels after transcription blockade, we then quantified the proteins after translation inhibition (cycloheximide). The p.L217L variant was associated with a slowdown of protein degradation visible after 5–7 h of treatment (Fig. 4d).

Effect of synonymous GATA2 c.649C>T variant on zebrafish hematopoiesis

For further analysis we selected the c.649C>T, p.L217L variant due to only partial reduction of the mutated allele expression in hematopoietic specimen of the P4. We hypothesized that the mutation may exert its effect on the protein level and aimed to determine if it alters zebrafish hematopoiesis. We used a previously published MO against gata2b [35] and visualized hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC) in zebrafish embryos by whole-mount in situ hybridization of the HSPC marker c-myb at 28 h post fertilization, when HSPCs arise from the dorsal aorta. Expectedly, gata2b inhibition resulted in a reduction of HSPCs in zebrafish embryos (Fig. 5a, top right) [35]. We then performed a phenotype rescue experiment by co-injecting gata2b MO with human GATA2 WT or Mut mRNA. Phenotype rescue (defined as medium/high phenotype; Supplementary Fig. 6) was achieved in 83% and 98% of embryos injected with WT and Mut mRNA, respectively, (Fig. 5b–d). However, we observed a significantly higher proportion of high phenotypes in animals rescued with Mut mRNA (42%) as compared with WT (19%), p < 0.05 (Fig. 5d right panel).

a Whole-mount in situ hybridization (WISH) performed at 28 h post fertilization (hpf) for c-myb in embryos injected with control or gata2b morpholino (MO). The arrows indicate the location of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPC) in the zebrafish aorta. The numbers in each picture indicate the number of embryos with depicted phenotype out of all embryos analyzed. b Rescue experiment performed on embryos co-injected with gata2b MO and human GATA2 WT or Mut (c.649C>T) mRNA. Transposase (TP) mRNA was used as a random control RNA with no expected impact. A substantial number of the Mut (c.649C>T) mRNA-injected morphants show an even stronger (high) staining than control TP mRNA-injected siblings. c Graphical representation of the rescue experiment. Distribution of phenotypes in all tested animals: high, indicates a stronger staining to the one of noninjected and standard control MO-injected embryos; medium, indicates a staining equivalent or approximately equivalent to the staining of noninjected and standard control MO-injected embryos; low, indicates a weaker staining compared with the staining of noninjected and standard control MO-injected embryos (deficiency of HSPCs). d Left panel: Graphical representation of percentage of embryos with medium or high staining for each treatment category. Right panel: Percentage of morphant embryos depicting high staining when injected with either WT or Mut (c.649C>T) mRNA. Each experiment was performed in triplicates (N = 3; mean ± SD, Student’s t test, *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001).

Discussion

GATA2 deficiency is a monogenic disorder known so far to be caused by heterozygous nonsynonymous mutations, whole gene deletions or intronic enhancer mutations, all of which result in haploinsufficiency. In this study, we report the identification of synonymous, RNA-deleterious mutations in GATA2 that accounted for 8.2% of all GATA2–mutated patients and 14.8% of cases with GATA2 exonic substitutions. In total, we identified nine patients harboring five distinct synonymous GATA2 variants that are either absent or exceedingly rare in general population: p.T117T, p.P472P, p.L217L, p.G327G, and p.A341A. Two of these (p.T117T and p.P472P) were encountered in multiple unrelated pedigrees, suggesting either independent mutational events or rare founders in the European population (which is possible at least for p.P472P present in gnomAD in 23 individuals of non-Finnish European ancestry). The phenotype of patients carrying synonymous variants resembled GATA2 deficiency. All of the patients were alive at last follow-up with exception of one patient who died from HSCT-related complications. Additional mutations in GATA2 were not identified. Other MDS-predisposing conditions were excluded based on clinical studies and WES/WGS in all patients with the exception of P6 who carried two VUS in the SAMD9 gene. No specific features demarcating GATA2 from SAMD9 syndrome were present in this patient; hypospadias are unspecific and had been reported in both conditions [36, 37]. At this point, we cannot rule out that in P6 both gene defects acted in a synergistic manner facilitating MDS development.

Computational prediction assigned an increased probability of missplicing to three of the five variants. Further assessment of mutation deleteriousness with existing in silico tools failed to ascribe pathogenic effects. Because of the difficulty in predicting deleteriousness, synonymous mutations have been generally left out in genomic studies. However, it is likely that many disease-causing mutations are being consistently overlooked—including mutations located in noncoding regions of the genome as well as synonymous variants. So far, little is known about the role of such mutations in hematopoietic malignancies due to lack of routine screening of the inter-/intragenic regions. Besides known recurrent deleterious mutations in the regulatory element of GATA2 [10] there are only few examples of noncoding mutations associated with BMF. Recently, two patients were reported with dyserythropoietic anemia and an intronic substitution in GATA1 gene that is 24 nucleotides upstream of the canonical splice acceptor site. This alteration resulted in reduced canonical splicing and increased use of an alternative splice acceptor site that causes a partial intron retention event [38]. Moreover, mutations in 5’UTR and deep intronic region of ELANE gene have been reported to be associated with severe congenital neutropenia [39]. Due to lack of studies integrating functional evaluation, the prevalence of such variants in Mendelian disorders is yet to be determined. It is remarkable that recent pancancer studies report acquired synonymous driver mutations at a rate of ~6–8% among all single-nucleotide changes found in human cancers [40]. This is strikingly similar to the proportion of (germline) synonymous mutations identified in our study. Mutations causing phenotypically severe hereditary disease are mainly introduced as random de novo events, and it is well accepted that purifying selection will eventually eliminate these deleterious alleles. This is especially valid in high-penetrance conditions, such as GATA2 deficiency that often manifests before the reproductive age and thus results in reduced fecundity.

There are multiple ways how synonymous substitutions can exert deleteriousness even though the amino acid sequence is not changed. As confirmed using three orthogonal approaches, all of the mutations found here resulted in a nearly complete and selective loss of the Mut transcript in hematopoietic cells, with the exception of c.649C>T, p.L217L that showed Mut allele reduction to ~20%. In contrast, paired analysis of two patients revealed a higher Mut allele expression in skin fibroblasts versus hematopoietic cells. Potential explanations for this discrepancy might be the variability of allelic expression across different tissues [41, 42] or the notion of context-dependent monoallelic expression observed for ~20% of human genes [43]. In addition, we observed that divergence in allelic ratio depends not only on the tissue analyzed but also on the stage of RNA processing. Strikingly, the mutation frequency in BM of two patients (c.351C>G and c.1023C>T) increased from nearly absent in mRNA to 30% in total RNA transcripts, implying that the defect manifests at a late stage of RNA maturation, at least for these two variants. Splicing disruption was predicted for three variants (c.351C>G, c.981G>A, and c.1023C>T); however, splicing analysis confirmed novel splicing pattern only for c.351C>G. This mutation resulted in aberrant transcripts with premature stop codon which makes it functionally equivalent to a frameshift-truncating mutation causing nonsense-mediated decay. For the remaining four mutations, no abnormal splicing was detected. It is conceivable that these Mut mRNAs are extremely unstable and subjected to a very rapid sequestration. Another potential explanation for loss of allelic expression is epigenetic silencing that could arise from aberrant promoter methylation. Supporting this, allelic disbalance due to hypermethylation was recently observed in one patient with GATA2 p.T354M mutation [44]. Synonymous variants can also affect translation and thus result in increased or decreased protein stability or function. Surprisingly, p.L217L Mut protein was slightly more stable in vitro, although its function (tested in vitro using the EMSA DNA gel shift assay at steady state, with ectopic GATA2 overexpression) seemed not to be affected. Further, this mutation not only rescued the GATA2-deficient phenotype in zebrafish, but also resulted in a significantly higher number of HSPCs in comparison with control animals. Higher stability of this mutated protein might potentially explain the relative increase in its functional properties in vivo. In analogy, it is known that moderate GATA2 overexpression enhances proliferation and self-renewal of progenitor cells [45]. We reason that the more efficient rescue of the morphant phenotype can be associated with higher stability of the p.L217L Mut, which is seen when transiently overexpressed in 293T cell line (Fig. 4d). Because of the challenging data (decrease of Mut RNA expression but higher protein stability of protein) we do question the pathogenicity of this mutation until additional biological data or patients are reported. Limited availability of patients’ primary specimens as well as instability of the transcripts with synonymous mutations precluded further mechanistic studies.

Reported diagnostic yields for WES/WGS in single individuals can reach ~40% and heavily rely on computational predictions [46, 47] which are difficult to achieve for synonymous mutations. Moreover, WES is limited to the analysis of coding regions only. Even though genome sequencing overcomes this constraint, it generates an enormous output of alterations within coding and noncoding regions of the genes. In setting of GATA2 deficiency, WGS would facilitate the detection of pathogenic intronic mutations in regulatory region in intron 4 (corresponding to +9.5 kb enhancer region) as well as whole gene and partial gene deletions. However, allelic loss on RNA level would be missed. The utility of transcriptome analysis was previously highlighted by the identification of disease-causing mutations in patients with negative exome or genome sequencing results, increasing the diagnostic rate by as much as 35% [48, 49]. Hence, we propose that diagnostic sequencing should incorporate a cascade approach where RNA sequencing follows inconclusive DNA analysis in patients with suspected disease. This approach is feasible not only for patients with GATA2 deficiency but also in patients with high index of suspicion for a specific Mendelian disorder but without a known pathogenic mutation. Our findings suggest that a straightforward Sanger or deep sequencing of cDNA would be sufficient to confirm the RNA-deleteriousness of a synonymous variant.

In summary, we demonstrate that a significant proportion of GATA2-deficient patients carry damaging synonymous alterations. These genetic changes, previously excluded from analysis due to their likely silent effect, should be incorporated into standard diagnostic pipeline for individuals with GATA2 disease phenotype. However, patients with other hereditary BM failure and MDS syndromes might also benefit from this extended diagnostic approach. In the long term, identification of pathogenic synonymous variants has the potential to improve genetic counseling, HSCT donor selection, and clinical outcomes.

Data availability

WES data have been deposited at the European Genome–phenome Archive (EGA), which is hosted by the EBI and the CRG, under accession number EGAS00001003817. Further information about EGA can be found on https://ega-archive.org “The European Genome–phenome Archive of human data consented for biomedical research”.

References

Hsu AP, Sampaio EP, Khan J, Calvo KR, Lemieux JE, Patel SY, et al. Mutations in GATA2 are associated with the autosomal dominant and sporadic monocytopenia and mycobacterial infection (MonoMAC) syndrome. Blood. 2011;118:2653–5.

Dickinson RE, Griffin H, Bigley V, Reynard LN, Hussain R, Haniffa M, et al. Exome sequencing identifies GATA-2 mutation as the cause of dendritic cell, monocyte, B and NK lymphoid deficiency. Blood. 2011;118:2656–8.

Hahn CN, Chong CE, Carmichael CL, Wilkins EJ, Brautigan PJ, Li XC, et al. Heritable GATA2 mutations associated with familial myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Genet. 2011;43:1012–7.

Pasquet M, Bellanne-Chantelot C, Tavitian S, Prade N, Beaupain B, Larochelle O, et al. High frequency of GATA2 mutations in patients with mild chronic neutropenia evolving to MonoMac syndrome, myelodysplasia, and acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2013;121:822–9.

Ostergaard P, Simpson MA, Connell FC, Steward CG, Brice G, Woollard WJ, et al. Mutations in GATA2 cause primary lymphedema associated with a predisposition to acute myeloid leukemia (Emberger syndrome). Nat Genet. 2011;43:929–31.

Dorn JM, Patnaik MS, Van Hee M, Smith MJ, Lagerstedt SA, Newman CC, et al. WILD syndrome is GATA2 deficiency: a novel deletion in the GATA2 gene. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5:1149–52.

Wlodarski MW, Hirabayashi S, Pastor V, Stary J, Hasle H, Masetti R, et al. Prevalence, clinical characteristics, and prognosis of GATA2-related myelodysplastic syndromes in children and adolescents. Blood 2016;127:1387–97.

Hirabayashi S, Wlodarski MW, Kozyra E, Niemeyer CM. Heterogeneity of GATA2-related myeloid neoplasms. Int J Hematol. 2017;106:175–82.

Wlodarski M, Collin M, Horwitz MS. GATA2 deficiency and related myeloid neoplasms. Seminars in Hematology. 2017;54:81–6.

Hsu AP, Johnson KD, Falcone EL, Sanalkumar R, Sanchez L, Hickstein DD, et al. GATA2 haploinsufficiency caused by mutations in a conserved intronic element leads to MonoMAC syndrome. Blood 2013;121:3830–7. S1-7

Hahn CN, Brautigan PJ, Chong CE, Janssan A, Venugopal P, Lee Y, et al. Characterisation of a compound in-cis GATA2 germline mutation in a pedigree presenting with myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myeloid leukemia with concurrent thrombocytopenia. Leukemia 2015;29:1795–7.

Cortes-Lavaud X, Landecho MF, Maicas M, Urquiza L, Merino J, Moreno-Miralles I, et al. GATA2 Germline Mutations Impair GATA2 Transcription, Causing Haploinsufficiency: Functional Analysis of the p.Arg396Gln Mutation. J Immunol. 2015;194:2190–8.

Sologuren I, Martinez-Saavedra MT, Sole-Violan J, de Borges de Oliveira E Jr, Betancor E, Casas I, et al. Lethal Influenza in Two Related Adults with Inherited GATA2 Deficiency. J Clin Immunol. 2018;38:513–26.

Chong CE, Venugopal P, Stokes PH, Lee YK, Brautigan PJ, Yeung DTO, et al. Differential effects on gene transcription and hematopoietic differentiation correlate with GATA2 mutant disease phenotypes. Leukemia 2018;32:194–202.

D’Souza I, Poorkaj P, Hong M, Nochlin D, Lee VM, Bird TD, et al. Missense and silent tau gene mutations cause frontotemporal dementia with parkinsonism-chromosome 17 type, by affecting multiple alternative RNA splicing regulatory elements. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5598–603.

Cartegni L, Krainer AR. Disruption of an SF2/ASF-dependent exonic splicing enhancer in SMN2 causes spinal muscular atrophy in the absence of SMN1. Nat Genet 2002;30:377–84.

Macaya D, Katsanis SH, Hefferon TW, Audlin S, Mendelsohn NJ, Roggenbuck J, et al. A synonymous mutation in TCOF1 causes Treacher Collins syndrome due to mis-splicing of a constitutive exon. Am J Med Genet A 2009;149A:1624–7.

Vidal C, Cachia A, Xuereb-Anastasi A. Effects of a synonymous variant in exon 9 of the CD44 gene on pre-mRNA splicing in a family with osteoporosis. Bone 2009;45:736–42.

Duan J, Wainwright MS, Comeron JM, Saitou N, Sanders AR, Gelernter J, et al. Synonymous mutations in the human dopamine receptor D2 (DRD2) affect mRNA stability and synthesis of the receptor. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12:205–16.

Wang D, Johnson AD, Papp AC, Kroetz DL, Sadee W. Multidrug resistance polypeptide 1 (MDR1, ABCB1) variant 3435C>T affects mRNA stability. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2005;15:693–704.

Nackley AG, Shabalina SA, Tchivileva IE, Satterfield K, Korchynskyi O, Makarov SS, et al. Human catechol-O-methyltransferase haplotypes modulate protein expression by altering mRNA secondary structure. Science 2006;314:1930–3.

Buhr F, Jha S, Thommen M, Mittelstaet J, Kutz F, Schwalbe H, et al. Synonymous Codons Direct Cotranslational Folding toward Different Protein Conformations. Mol cell 2016;61:341–51.

Brest P, Lapaquette P, Souidi M, Lebrigand K, Cesaro A, Vouret-Craviari V, et al. A synonymous variant in IRGM alters a binding site for miR-196 and causes deregulation of IRGM-dependent xenophagy in Crohn’s disease. Nat Genet 2011;43:242–5.

Simhadri VL, Hamasaki-Katagiri N, Lin BC, Hunt R, Jha S, Tseng SC, et al. Single synonymous mutation in factor IX alters protein properties and underlies haemophilia B. J Med Genet. 2017;54:338–45.

Wehr C, Grotius K, Casadei S, Bleckmann D, Bode SFN, Frye BC, et al. A novel disease-causing synonymous exonic mutation in GATA2 affecting RNA splicing. Blood 2018;132:1211–5.

Baumann I, Niemeyer CMBJ, Shannon K WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissues. Lyon: IARC Press; 2008. p. 104–7.

Vardiman JW, Thiele J, Arber DA, Brunning RD, Borowitz MJ, Porwit A, et al. The 2008 revision of the World Health Organization (WHO) classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia: rationale and important changes. Blood 2009;114:937–51.

Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood 2016;127:2391–405.

Pastor V, Hirabayashi S, Karow A, Wehrle J, Kozyra EJ, Nienhold R, et al. Mutational landscape in children with myelodysplastic syndromes is distinct from adults: specific somatic drivers and novel germline variants. Leukemia. 2016;31:759–62.

Bluteau O, Sebert M, Leblanc T, Peffault de Latour R, Quentin S, Lainey E, et al. A landscape of germ line mutations in a cohort of inherited bone marrow failure patients. Blood 2018;131:717–32.

Buonocore F, Kuhnen P, Suntharalingham JP, Del Valle I, Digweed M, Stachelscheid H, et al. Somatic mutations and progressive monosomy modify SAMD9-related phenotypes in humans. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:1700–13.

Narumi S, Amano N, Ishii T, Katsumata N, Muroya K, Adachi M, et al. SAMD9 mutations cause a novel multisystem disorder, MIRAGE syndrome, and are associated with loss of chromosome 7. Nat Genet 2016;48:792–7.

Huang Z, Dore LC, Li Z, Orkin SH, Feng G, Lin S, et al. GATA-2 reinforces megakaryocyte development in the absence of GATA-1. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:5168–80.

Goardon N, Marchi E, Atzberger A, Quek L, Schuh A, Soneji S, et al. Coexistence of LMPP-like and GMP-like leukemia stem cells in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell 2011;19:138–52.

Butko E, Distel M, Pouget C, Weijts B, Kobayashi I, Ng K, et al. Gata2b is a restricted early regulator of hemogenic endothelium in the zebrafish embryo. Development 2015;142:1050–61.

Schwartz JR, Wang S, Ma J, Lamprecht T, Walsh M, Song G, et al. Germline SAMD9 mutation in siblings with monosomy 7 and myelodysplastic syndrome. Leukemia 2017;31:1827–30.

Novakova M, Zaliova M, Sukova M, Wlodarski M, Janda A, Fronkova E, et al. Loss of B cells and their precursors is the most constant feature of GATA-2 deficiency in childhood myelodysplastic syndrome. Haematologica 2016;101:707–16.

Abdulhay NJ, Fiorini C, Verboon JM, Ludwig LS, Ulirsch JC, Zieger B, et al. Impaired human hematopoiesis due to a cryptic intronic GATA1 splicing mutation. J Exp Med. 2019;216:1050–60.

Makaryan V, Zeidler C, Bolyard AA, Skokowa J, Rodger E, Kelley ML, et al. The diversity of mutations and clinical outcomes for ELANE-associated neutropenia. Curr Opin Hematol. 2015;22:3–11.

Supek F, Minana B, Valcarcel J, Gabaldon T, Lehner B. Synonymous mutations frequently act as driver mutations in human cancers. Cell 2014;156:1324–35.

Pirinen M, Lappalainen T, Zaitlen NA, Consortium GT, Dermitzakis ET, Donnelly P, et al. Assessing allele-specific expression across multiple tissues from RNA-seq read data. Bioinformatics 2015;31:2497–504.

Wilkins JM, Southam L, Price AJ, Mustafa Z, Carr A, Loughlin J. Extreme context specificity in differential allelic expression. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:537–46.

Serre D, Gurd S, Ge B, Sladek R, Sinnett D, Harmsen E, et al. Differential allelic expression in the human genome: a robust approach to identify genetic and epigenetic cis-acting mechanisms regulating gene expression. PLoS Genet 2008;4:e1000006.

Al Seraihi AF, Rio-Machin A, Tawana K, Bodor C, Wang J, Nagano A, et al. GATA2 monoallelic expression underlies reduced penetrance in inherited GATA2-mutated MDS/AML. Leukemia. 2018;32:2502–7.

Nandakumar SK, Johnson K, Throm SL, Pestina TI, Neale G, Persons DA. Low-level GATA2 overexpression promotes myeloid progenitor self-renewal and blocks lymphoid differentiation in mice. Exp Hematol 2015;43:565–77.e1-10.

Taylor JC, Martin HC, Lise S, Broxholme J, Cazier JB, Rimmer A, et al. Factors influencing success of clinical genome sequencing across a broad spectrum of disorders. Nat Genet 2015;47:717–26.

Ji J, Shen L, Bootwalla M, Quindipan C, Tatarinova T, Maglinte DT, et al. A semi-automated whole exome sequencing workflow leads to increased diagnostic yield and identification of novel candidate variants. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2019;5:a003756.

Cummings BB, Marshall JL, Tukiainen T, Lek M, Donkervoort S, Foley AR, et al. Improving genetic diagnosis in Mendelian disease with transcriptome sequencing. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9:eaal5209.

Kremer LS, Bader DM, Mertes C, Kopajtich R, Pichler G, Iuso A, et al. Genetic diagnosis of Mendelian disorders via RNA sequencing. Nat Commun 2017;8:15824.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from Fritz Thyssen Foundation 10.17.1.026MN (to MWW and ET); Deutsche Kinderkrebsstiftung DKS 2017.03, ERAPerMed by German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) 2018-123/01KU1904, and Deutsche Krebshilfe 109005 (to MWW); José Carreras Leukemia Foundation (to VBP); Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) 322977937/GRK2344 “MeInBio–BioInMe” (to ET and MB); Marie Curie Career Integration 631432 “Bloody Signals”, and DFG CIBSS-EXC-2189 390939984 (to ET), Baden-Württemberg LGFG stipend (to EJK), DFG EXC 22167-390884018 (to HB) and CRC850 (to MB), BMBF CoNfirm 01ZX1708F (to MB), and BMBF MyPred Network for young individuals with syndromes predisposing to myeloid malignancies (to MWW, ME, GG, CF, BS, and CMN). We are very grateful to Ayami-Yoshimi Nöllke, Lheanna Klaeyle, Sophie Krüger, Sandra Zolles, Christina Jäger, Sophia Hollander, Marco Teller, Ali-Riza Kaya, Alexandra Fischer, Wilfried Truckenmüller, Peter Nöllke, and Anne Strauss (Freiburg) for excellent assistance in diagnostic workup, laboratory work, and data management, and Prof. Dr. Rudolf Grosschedl (Max Planck Institute Freiburg), Dr. Claudia Wehr, and Dr. Ulrich Salzer (Freiburg) for helpful discussions. The authors also thank all members of the European Working Group of MDS in Childhood (EWOG-MDS) for performing reference examinations (pathology, cytogenetics, molecular genetics), HSCT or other forms of patient care. This work was performed within the European Reference Network for Paediatric Cancer (ERN-PAEDCAN). The authors acknowledge the contribution of the Center of Inborn and Acquired Blood Diseases at the Freiburg Center for Rare Diseases, and the Hilda Biobank at the Department of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Freiburg, Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

EJK and MWW designed the study. EJK, MWW, VBP, ME, and ET contributed to manuscript conception. EJK, VBP, EAS, RKV, SH, DL, LP, MT, PM, MB, HB, PS, and MWW performed genomic studies and analyzed data. EJK, ET, SSS, SL, PS, and MD accomplished functional studies. MC, EM, ME, RP, LP, MT, CK, AC, HH, VH, KK, RM, BM, MD, MS, OS, JS, EM, MU, GG, CF, BS, FL, CMN, and MWW were involved in the patient care and testing. All authors contributed to the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

Primary patients’ samples were obtained after written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was approved by the local Ethics Committee (CPMP/ICH/135/95). All animal experiments were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations, approved by the review committee of the Max Planck Institute of Immunobiology and Epigenetics and the Regierungspraesidium Freiburg, Germany (license Az 35-9185.81/G-14/95).

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kozyra, E.J., Pastor, V.B., Lefkopoulos, S. et al. Synonymous GATA2 mutations result in selective loss of mutated RNA and are common in patients with GATA2 deficiency. Leukemia 34, 2673–2687 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-020-0899-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41375-020-0899-5

This article is cited by

-

GATA2 Deficiency: Predisposition to Myeloid Malignancy and Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation

Current Hematologic Malignancy Reports (2023)

-

A Nationwide Study of GATA2 Deficiency in Italy Reveals Novel Symptoms and Genotype–phenotype Association

Journal of Clinical Immunology (2023)

-

A Nationwide Study of GATA2 Deficiency in Norway—the Majority of Patients Have Undergone Allo-HSCT

Journal of Clinical Immunology (2022)

-

Advances in germline predisposition to acute leukaemias and myeloid neoplasms

Nature Reviews Cancer (2021)

-

Review of guidelines for the identification and clinical care of patients with genetic predisposition for hematological malignancies

Familial Cancer (2021)