Abstract

Synucleinopathies are a group of neurodegenerative diseases characterized by the accumulation of insoluble, aggregated α-synuclein (αS) pathological inclusions. Multiple system atrophy (MSA) presents with extensive oligodendroglial αS pathology and additional more limited neuronal inclusions while most of the other synucleinopathies, such as Parkinson’s disease and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), develop αS pathology primarily in neuronal cell populations. αS biochemical alterations specific to MSA have been described but thorough examination of these unique and disease-specific protein deposits is further warranted especially given recent findings implicating the prion-like nature of synucleinopathies perhaps with distinct strain-like properties. Taking advantage of an extensive panel of antibodies that target a wide range of epitopes within αS, we investigated the distinct properties of the various types of αS inclusion present in MSA brains with comparison to DLB. Brain biochemical fractionation followed by immunoblotting revealed that the immunoreactive profiles were significantly more consistent for DLB than for MSA. Furthermore, epitope-specific immunohistochemistry varied greatly between different types of MSA αS inclusions and even within different brain regions of individual MSA brains. These studies highlight the importance of using a battery of antibodies for adequate appreciation of the various pathology in this distinct synucleinopathy. In addition, it can be posited that if the spread of pathology in MSA undergoes prion-like mechanisms, “strains” of αS aggregated conformers must be inherently unstable and readily mutable, perhaps resulting in a more stochastic progression process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Synucleinopathies are neurodegenerative diseases characterized by the aggregation of α-synuclein (αS) in the form of pathological inclusions in neurons, and in some diseases in glia [1,2,3,4,5,6]. In multiple system atrophy (MSA), αS-reactive inclusions are found primarily in the cytosol of oligodendrocytes, termed glial cytoplasmic inclusions (GCIs), but may also be less frequently found within neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions (NCIs) or neuronal nuclear inclusions (NNIs) [7, 8]. In contrast, in other synucleinopathies, such as Parkinson’s disease (PD) and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), αS pathology characteristically manifests as Lewy body and Lewy neurite inclusions within neurons [3, 9]. In MSA, αS pathology predominantly presents in the striatum, midbrain, pons, medulla, and cerebellum, with the relative burden of disease varying per region with respect to the disease subtypes of olivo-ponto-cerebellar atrophy (OPCA, MSA-C) or striatonigral degeneration (SND, MSA-P) [10,11,12]. In Lewy inclusion diseases, αS pathology is stratified based on its involvement of brainstem, limbic, and cortical structures, as well as amygdala and olfactory bulb [13]. Furthermore, as a clinical disease, MSA is consistently the more aggressive synucleinopathy, with earlier age of onset and a median survival from date of onset of only 9 years. In comparison, the Lewy Body diseases exhibit a wide variability of progression, in some cases demonstrating a prodromal period lasting decades and a median post-diagnosis survival in excess of a decade [14,15,16].

These distinctive differences between MSA and Lewy Body diseases suggest a significant difference between the biochemical properties of their respective underlying aggregated forms of αS. A growing body of in vitro and in vivo evidence supports the existence of such a difference. αS that polymerizes into fibrils found in MSA GCIs possess a wider, more tubular ultrastructure as compared with Lewy Body fibrillar αS, with additional evidence suggesting that NCIs and NNIs are also distinct pathological structures [1, 6,7,8, 17, 18]. Gaining traction is the hypothesis that neurodegenerative diseases—including the synucleinopathies—are in fact “prion-like proteinopathies,” wherein a substrate of aberrant, misfolded proteins induce (“seed”) the formation and propagation of other aberrant, misfolded proteins in a progressively magnified manner [4, 19, 20]. This disease model lends a theoretical scaffold for which to conceptualize the biochemical differences between MSA and Lewy Body αS. As prion diseases include different “strains” of prion proteins, the “prion-like proteinopathies” of MSA and Lewy Body diseases could represent different “strains” of α-synucleinopathy. Additionally, experimental evidence comparing seeding capabilities of MSA and PD patient brain samples further supports the idea that the MSA αS strain represents a unique entity [21,22,23].

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for αS represents one of the most commonly used adjunctive tools used in the neuropathological assessment of the α-synucleinopathies in post-mortem human brain tissue. Currently, the same αS-antibodies are applied to the evaluation of both MSA and the Lewy Body diseases. Given the growing evidence in support of distinctive biochemical αS strains, a “one antibody fits all” approach to evaluating these diseases may be inadequate. We previously described a panel of antibodies capable of targeting a wide range of epitopes of αS [24]. These antibodies displayed various affinities for αS when comparing synucleinopathies, and as such, represent a set of highly valuable reagents to investigate modifications, structural or post-translational, which could contribute to or help define individual αS strains. Utilizing this antibody panel exhibiting a diverse αS epitope repertoire, we set out to investigate MSA as a unique synucleinopathy by immunohistochemically describing the disease in the context of αS-specific alterations.

Materials and methods

Autopsy case material

Human brain tissue was obtained through the University of Florida Neuromedicine Human Brain Tissue Bank according to protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board. Post-mortem pathological diagnoses were made according to neuropathological criteria proposed by the Neuropathology Working Group on MSA [25]. Six MSA cases were studied that included the two major pathological subtypes: striato-nigral degenerations (SND/MSA-P: 4 cases, ID #’s 1, 2, 3, and 5) and olivo-ponto-cerebellar atrophies (OPCA/MSA-C: 2 cases, ID #’s 4 and 6). These were classified into the different subtypes based on clinical presentation and distribution of αS pathology burden [10,11,12]. For immunoblot analysis and comparison to MSA, controls were obtained from cerebellar white matter of three aged patients without neurological disease. Cingulate cortex gray matter from three cases of DLB and two aged patients without neurological disease were also obtained for comparison (Table 1).

Immunoblotting analyses

Protein samples were resolved by electrophoresis on 15% polyacrylamide gels, then electrophoretically transferred to 0.2 µm pore size nitrocellulose membranes in carbonate transfer buffer (10 mM NaHCO3, 3 mM Na2CO3, pH 9.9, 20% methanol). Membranes were blocked with 5% milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) for 1 h, then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies diluted in 5% milk/TBS. Following washing with TBS, blots were incubated with HRP conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Jackson Immuno Research Labs, West Grove, PA) diluted in 5% milk/TBS for 1 h. Following washing with TBS, protein bands were visualized using Western Lightning-Plus ECL reagents (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA) and images were captured using the GeneGnome XRQ system and GeneTools software (Syngene, Frederick, MD).

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin embedded, formalin fixed, sequential tissue sections were deparaffinized with xylenes, and sequentially rehydrated with graded ethanol solutions (100–70%). Antigen retrieval was performed by incubating sections in 0.05% Tween-20 in a steam bath for 60 min. Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched with 1.5% hydrogen peroxide/0.005% Triton-X-100/PBS for 20 min followed by a thorough wash in running water. Slides that received additional formic acid antigen retrieval were immersed in 70% formic acid for 30 min at room temperature following quenching of endogenous peroxidase activity and then washed in running water for 30 min. Slides that received additional proteinase K antigen retrieval were immersed in 50 µg/mL PK (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany) in PK buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 100 mM NaCl, 0.1% Nonidet-P40) for 1 h at 55 °C then washed in running water for 30 min. Sections were blocked with 2% FBS/0.1 M Tris, pH 7.6 then incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4 °C. Following washing with 0.1 M Tris, pH 7.6, sections were incubated with biotinylated horse anti-mouse IgG (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) diluted in 2% FBS/0.1 M Tris pH 7.6 for 1 h. Sections were then washed with 0.1 M Tris, pH 7.6, and incubated with streptavidin-conjugated HRP (Vectastain ABC kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) diluted in 2% FBS/0.1 M Tris pH 7.6 for 1 h. Sections were washed with 0.1 M Tris, pH 7.6, and then colorimetric development was completed using 3, 3′diaminobenzidine (DAB kit; KPL, Gaithersburg, MD). Reactions were stopped by immersing the slides in 0.1 M Tris, pH 7.6, and sections were counterstained with Mayer’s hematoxylin (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Slides were dehydrated with an ascending series of ethanol solutions (70–100%) followed by xylenes, and coverslipped using cytoseal (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Inclusion pathology was observed and qualitatively assessed by two independent observers and confirmed by a third observer.

Sequential biochemical fractionation of human nervous tissue

Tissues were frozen at −80 °C and thawed on ice on day of processing. MSA samples were retrieved from subcortical cerebellar white matter of cases 2, 3 and 4, and DLB samples were retrieved from cingulate cortex gray matter. Control cases for cerebellar white matter and control cases for cingulate cortex gray matter were retrieved from control patients without neurological disease. As depicted in Fig. 1, nervous tissue was homogenized with 3 volumes per gram of tissue with high salt (HS) buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 750 mM NaCl, 20 mM NaF, 5 mM EDTA) containing protease inhibitor cocktail (1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 1 mg/ml each of pepstatin, leupeptin, N-tosyl-L-phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone, N-tosyl-lysine chloromethyl ketone, and soybean trypsin inhibitor). The HS tissue homogenates then underwent sedimentation at 100,000 × g for 20 min and the supernatants were saved as the HS fraction. Pellets were resuspended in 3 volumes per gram of tissue with HS buffer with 1% Triton X-100 (HS/T buffer) and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 20 min. The supernatants were saved as the HS/T fraction. The pellets were then homogenized in 3 volumes per gram of tissue with HS buffer with 1 M sucrose and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 20 min to float the myelin, which was discarded. Pellets were homogenized in 2 volumes per gram of tissue with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) containing protease inhibitors and centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 20 minutes. Supernatants were saved as the RIPA fraction. Pellets were then homogenized in 1 volume per gram of tissue with 2% SDS/4 M urea by probe sonication and saved as the Urea/SDS fractions. Protein concentrations of all fractions were determined by BCA assay using bovine serum albumin as the standard. SDS sample buffer was added to sequential fractions which were incubated for 10 minutes at 100 °C for the HS fraction or at room temperature for SDS/U fraction, and then frozen at −80 °C. Equal amounts of protein (20 μg for HS and 10 μg for SDS/U fractions) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblot.

Antibodies

Mouse monoclonal antibodies 4A7 and 5D12 were generated against a synthetic peptide (CTKQGVAEAAGKTKEGVLYVGS) corresponding to amino residues 22–42 in human αS with an added N-terminal Cys generated as a service by Genescript and conjugated to Imject maleimide activated mariculture keyhole limpet hemocyanin (mcKLH; Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Similarly, antibody 3H11 was generated with a synthetic peptide (CKTKEGVVHGVATVAEKTKEQ) corresponding to amino residues 43–62 in human αS and conjugated to mcKLC. These antibodies were generated by immunizing mice and procedures previously described in Dhillon et. al. 2017 [24]. Other non-phospho-specific antibodies SNL4, 9C10, 33A-3F3, and 94–3A10 were previously described [24, 27]. αS phospho-Ser129 (pSer129) antibodies 81A and LS4–2G12 were previously characterized [26, 28, 29] and EP1536Y was obtained from Abcam (Table 2).

Results

To investigate the immunoreactive profiles of αS found within glial and neuronal inclusions of MSA we utilized six cases of pathologically confirmed MSA and performed IHC on three brain regions commonly affected; cerebellum, pons, and striatum (Table 1). These cases were probed with several αS antibodies, with epitopes spanning the αS protein, and qualitatively graded based on staining intensity of GCIs, NCIs, and NNIs on a four-tiered scale, with “0” representing non-reactivity, “1” mild, “2” moderate, and “3” representing the strongest level of reactivity (Table 2, Fig. 2). Differences in antibody reactivity profiles did not delineate MSA subtypes, nevertheless, GCI pathology was most consistently detected with antibodies EP1536Y and 94–3A10. N-terminal antibodies, with the exception of SNL-4, were the least immunoreactive for GCIs. Antibodies 4A7, 5D12, and 9C10 were generally less robust in detecting GCI pathology across cases, were still capable of targeting NCIs, but never identified NNIs. Antibodies 33A-3F3, 81A, and LS4–2G12 displayed a generally modest reactivity for GCIs, occasionally reaching qualitative grade 3 in pathology burden for select cases and brain regions. Staining profiles for neuronal inclusion pathology proved to be markedly variable between antibodies. With respect to the cerebellum, across cases, no NNIs were observed, and NCIs were sporadically detected by certain antibodies in cases 3, 4, and 5 (Fig. 2a). Antibodies EP1536Y and 94–3A10, reliably detected GCIs in the cerebellum of each case, but were observed to highlight the NCIs of different cases, indicating variations at specific epitopes between cases with respect to neuronal inclusions. In the pons and striatum, NCIs and NNIs were generally more readily detectable, but variability between the cases in which they were detected, as well as inclusion type (nuclear vs. cytoplasmic), was once again apparent (Fig. 2b, c).

Immunohistochemical grading of αS pathology in different MSA cases. A panel of αS antibodies was for the immunohistochemical staining of six confirmed cases of MSA in the cerebellum (a), pons (b), and striatum (c). Glial cytoplasmic inclusions (red bars), neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions (blue bars), and neuronal nuclear inclusions (green bars), were graded on a qualitative assessment of staining intensity by two independent observers and confirmed by a third. The findings are summarized as (0) absent, [1] mild, [2] moderate, and [3] strong

Antibodies SNL-4, 33A-3F3, 81A, and 94–3A10 were found to produce varying degrees of nonspecific background staining across all brain regions and cases. Additionally, antibodies SNL-4, 33A-3F3, 81A, LS4–2G12, EP1536Y, and 94–3A10 consistently detected gray matter neurites in the pons of cases 2, 3, 4, and 6. The pons of case 5 was not fully retrievable during dissection, and ultimately consisted of predominantly middle cerebellar peduncle, accounting for the lack of observable neurites and neuronal inclusions. Case 1, which displayed a marked reduction in N-terminal immunoreactivity across brain regions, was notably free of neurites within the pons. Neurites were also detected in the cerebellum of every case except case 4 by antibody 81A. Antibody 81A was the only antibody that revealed white matter axonal reactivity, attributable to its known cross reactivity with neurofilament protein [29].

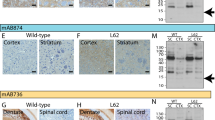

To better understand the protein alterations associated with varied histological immunoreactivity on GCIs, cerebellar subcortical white matter was harvested from cases 2, 3 and 4 and subjected to sequential biochemical fractionation followed by immunoblotting with select antibodies targeting epitopes that span the αS protein (Fig. 3). Cases 2, 3, and 4 correspond to lanes M1, M2, and M3, respectively. For comparison we also performed similar analysis from the cingulate cortex of DLB patients with abundant Lewy pathology. All the HS soluble fractions from control, MSA and DLB patients contained αS, but only the SDS-urea fractions from MSA and DLB patients presented with αS consistent with the disease-specific aggregation of αS. Modified or aggregated forms of αS migrating as higher molecular mass species on SDS-PAGE were more readily detected with antibodies within the N-terminal region of αS (Fig. 3). In addition, the banding pattern profiles for these higher molecular species was more consistent for DLB extracts than for MSA.

Biochemical comparisons of αS immunological profiles in MSA and DLB brain specimens. Immunoblot comparison of αS found in the cerebellum white matter of MSA case 2 (lane M1), case 3 (lane M2), and case 4 (lane M3), with αS found in cingulate cortex of three confirmed DLB patients (D1, D2, and D3). Control samples C1, C2, and C3 come from cerebellar white matter (WM) of patients with no neurodegenerative phenotypes, and control sample C4 and C5 come from cingulate cortex gray matter (GM) of patients with no neurodegenerative phenotypes. Samples were sequentially fractionated as described in “Materials and Methods”. Soluble high salt compared to detergent insoluble and urea/SDS samples from each case were loaded on separate lanes of SDS-polyacrylamide gels that were then analyzed by immunoblotting with the respective αS antibodies as indicated above each panel. The mobilities of molecular mass markers are indicated on the left of each blot. The arrows on the right depict monomeric αS

Since the various epitopes were present to some degree in each biochemical fraction but in many cases were not readily identifiable through IHC, we subjected MSA case 1 to additional antigen retrieval with formic acid (Figs. 4 and 5). Antigen retrieval with proteinase K proved counter-productive, as it disrupted the tissue and prevented adequate antibody detection (data not shown). With the addition of formic acid antigen retrieval, every antibody showed an increase in staining intensity, and GCIs that were previously unappreciated by certain antibodies became readily detectable. Furthermore, additional antigen retrieval revealed a greater burden of neuronal pathology, with both nuclear and cytoplasmic inclusions that were previously undetectable by even our most proficient antibody, 94–3A10. With such a profound effect on MSA pathology we conducted comparative investigation of formic acid antigen retrieval on cingulate cortex tissue from the three DLB cases utilized in the immunoblotting analysis with the relatively strongest antibody 94–3A10, and one of our relatively weakest, 4A7 (Fig. 6). Antibody 94–3A10 was largely unaffected by additional antigen retrieval when observing Lewy bodies but detection and relative burden of Lewy neurites was markedly enhanced. In contrast, without formic acid antigen retrieval antibody 4A7 detected Lewy bodies mild to moderately and did not identify Lewy neurites. With additional antigen retrieval Lewy body detection was increased and Lewy neurites could be identified.

Formic acid antigen retrieval of glial cytoplasmic inclusion pathology. Immunohistochemical grading of glial cytoplasmic inclusion pathology in case 1 by a panel of αS antibodies in the cerebellum, pons, and striatum, comparing additional formic acid antigen retrieval (blue bars), to standard steam bath (red bars). Qualitative assessment of staining intensity was completed by two independent observers and confirmed by a third; the finding are summarized as (0) absent, [1] mild, [2] moderate, and [3] strong

Representative immunohistochemistry of formic acid antigen retrieval on MSA tissue. Immunohistochemical staining of MSA case 1 in the cerebellum, pons, and striatum, with (+) and without (−) additional formic acid antigen retrieval utilizing antibodies 94–3A10 (a), 33A-3F3 (b), 3H11 (c), 4A7 (d), and 9C10 (e). Bar = 50 µm

Representative immunohistochemistry of formic acid antigen retrieval on DLB tissue. Immunohistochemical staining of DLB case 2 in the cingulate cortex gray matter, with (+) and without (−) additional formic acid antigen retrieval, utilizing antibodies 94–3A10 and 4A7. Arrows indicate Lewy bodies and arrowheads indicate Lewy neurites. Bar = 50 µm

Discussion

We previously reported on the relative ability of our panel of antibodies to detect αS pathology in different models of synucleinopathy [24]. These antibodies revealed significant variation in the immunoreactive presentation of αS across synucleinopathies, confirming previous reports on the biochemical distinctions that exist between the αS inclusions in MSA and the αS inclusions present in Lewy Body diseases [30]. To investigate this further, we examined the cerebellum, pons, and striatum of six individuals with pathologically confirmed MSA. Immunohistochemical analysis revealed substantial variation in αS protein deposition across cases, and across different brain regions within individual cases.

In line with prior investigations we found GCIs to be the predominant form of αS pathology [11, 25, 31, 32]. The only correlation with respect to MSA subtype and inclusion formation can be found in striatal neuronal inclusions. Cases 1, 2, 3, and 5 are of the MSA-P subtype while cases 4 and 6 were determined to be MSA-C. Throughout the cerebellum and pons no stratification can be seen in terms of cell inclusion tropism or staining intensity with relation to MSA subtype. In striatal sections however, neuronal inclusions can only be found in MSA-P cases. This finding requires further verification as our relatively small sample size likely does not represent the entire breadth of this disease, which has been shown to vary substantially in previous reports [10, 33, 34]. These striatal neuronal inclusions were not completely detectable by any one antibody as αS pathology burden varied widely, for example case 1 was markedly less burdened by αS pathology with inclusions that were less detectable.

The performances of antibodies 94–3A10 and EP1536Y were particularly notable, demonstrating consistently robust reactivity for GCI αS across all cases and brain regions. While both antibodies had a tendency to produce a mild, nonspecific background blush, and highlighted neurites in gray matter structures (most saliently in the pons), they did not show cross-reactivity for axonal neurofilament such as that exhibited by antibody 81A [29]. Every antibody was adept at detecting varying forms of neuronal pathology but did so in case and brain region dependent manner. 94–3A10 and EP1536Y consistently exhibited the highest staining intensity for these relatively rarer inclusion types, providing for qualitatively easier detection. It is interesting to note that while 94–3A10 and EP1536Y showed similarly robust neuronal inclusion staining, for a given case in which both antibodies showed neuronal pathology, the brain regions in which they detected neuronal pathology differed. These results indicate that MSA neuronal αS inclusions may in fact exhibit significant inclusion variability between brain regions within even a single patient, such that in order to fully appreciate the full extent of neuronal αS pathology in MSA, the use of multiple αS antibodies with differential epitope specificities is necessary. In practical terms, these results show that 94–3A10 and EP1536Y represent comparably robust immunohistochemical markers of both glial and neuronal αS inclusions in MSA, exhibiting improved specificity for αS pathology over antibody 81A with regard to their lack of cross-reactivity for axonal neurofilament and reactivity to the diverse protein deposits.

Biochemical fractionation analysis of MSA cerebellar white matter and DLB cingulate cortex gray matter revealed unique immunoblot protein banding profiles that showed considerable variation between different types of synucleinopathies, but that were more conserved for DLB while quite variable in patients with MSA. This variation could represent disease dependent processes that cause recognizable alterations to specific epitopes, as suggested by the distinctive banding patterns between diseases. Generally, N-terminal antibodies displayed the greatest reactivity for higher molecular mass αS species on SDS-PAGE but also presented with more discrepancies in staining intensity by IHC, indicating that this region of the protein undergoes disease-specific alterations that may differentiate the underlying pathogenesis of these two distinct synucleinopathies.

While the trend towards the N-terminus being less immunoreactive was still apparent, the use of additional antigen retrieval in the form of formic acid exposed the presence of the entire αS protein within GCIs. Moreover, these experiments revealed epitope modifications that appear to differ between brain regions. This is exemplified by antibody 33A-3F3, which detected αS pathology in the cerebellum without formic acid but lost GCI reactivity to a degree in the pons and became thoroughly absent in the striatum, requiring formic acid antigen retrieval for adequate visualization (Fig. 5b). This would indicate that within a single patient αS undergoes modifications that differ between brain regions, such that identifying one “protein strain” as the pathological culprit in a patient might not account for all variations that have developed. There is evidence that suggests that the cellular environment can be responsible for the formation of distinct strains of αS, but as our data demonstrates, pathology can vary substantially within the same brain region across patients suggesting additional disease processes [23].

We previously described significant immunohistochemical differences between synucleinopathies during our previous pathological assessments using an extensive panel of αS antibodies, demonstrating that N-terminal αS antibodies strongly detected Lewy body inclusions while very weakly labelling GCIs [24]. To complement these findings we performed formic acid antigen retrieval on DLB cases with an N-terminal αS specific antibody (4A7) and a C-terminal αS specific antibody (94–3A10). Immunoreactivity of Lewy bodies was not significantly increased with formic acid retrieval for 94–3A10 while Lewy neurite labelling was somewhat enhanced. In contrast, we noted improved labeling of Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites for 4A7, however this was not as striking as for MSA pathology, suggesting disease-specific altered conformations or post-translational modifications akin to prion-like strain properties.

For a given disease like MSA, current diagnostic tools do not address the variability of which αS is capable, and as our findings suggest, not even within even a single patient. The necessity for additional antigen retrieval in visualization of amyloid-β deposits in Alzheimer’s disease patients has been previously established and current investigative methods for detection of amyloid beta pathology now use these additional methods for better appreciation of disease burden [35, 36]. Investigations of variability in αS pathology based upon differing forms of antigen retrieval were conducted around the same time in Lewy body diseases by Beach et al. [37] but as MSA likely represents a unique subset of synucleinopathy diseases, and as the results herein suggest, future examination of αS in tissue samples from patients with synucleinopathy disease should include formic acid antigen retrieval and several antibodies to fully visualize all aspects of pathology [37]. While our proteinase K protocol was ineffective, possibly due to its addition to a steam bath as opposed to in lieu of one, this does not mean a thorough investigation of differing proteinase K antigen retrieval methods will not reveal additional information.

Our current findings may present matters to consider for those undertaking the task of consolidating a stratification scheme to MSA, such as that which exists for the Lewy Body diseases. Well-designed studies have investigated the distribution of MSA inclusions throughout the human neuraxis across cases of variable disease duration and αS burden, in an effort to elucidate an orderly topographic progression [11, 31, 32]. Our findings suggest that the challenge of identifying an orderly progression of inclusions in MSA—from which a grading construct may ultimately be derived—is further compounded by the limitations of adopting approaches utilizing only a single antibody to identify αS pathology. To appreciate the true total burden of MSA inclusion pathology, both glial and neuronal, it may in fact be necessary to expand from the solitary lens of the pSer129 epitope. Additionally, the limitation of a solitary epitope approaches may well have ramifications with respect to our understanding of disease pathophysiology. Previous studies have noted that neuronal loss in MSA correlates imperfectly with the presence of local neuronal inclusions, leading investigators to infer that neuronal loss may rather be predominantly a result of glial white matter pathology, both local and distant [18, 38,39,40]. Our findings, however, indicate that neuronal inclusions “invisible” to pSer129 antibodies may be highlighted by antibodies specific to different epitopes, such as 94–3A10, and additional antigen retrieval. Thus, areas of neuronal loss thought to be devoid of neuronal inclusions may in fact show neuronal αS burden through an expanded antibody toolkit, modifying our understanding of pathologic relationships within MSA.

References

Waxman EA, Giasson BI. Molecular mechanisms of α-synuclein neurodegeneration. Biochim Biophys Acta - Mol Basis Dis. 2009;1792:616–24.

Cookson MR. The Biochemistry of Parkinson’s Disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 2005 Jun;74:29–52.

Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Del Tredici K, Braak H. 100 years of Lewy pathology. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;9:13–24.

Uchihara T, Giasson BI. Propagation of alpha-synuclein pathology: hypotheses, discoveries, and yet unresolved questions from experimental and human brain studies. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131:49–73.

Goedert M. The awakening of α-synuclein. Nature. 1997;388:232–3.

Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein and neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:492–501.

Burn DJ, Jaros E. Multiple system atrophy: cellular and molecular pathology. Mol Pathol. 2001;54:419–26.

Arima K, Murayama S, Mukoyama M, Inose T. Immunocytochemical and ultrastructural studies of neuronal and oligodendroglial cytoplasmic inclusions in multiple system atrophy. 1. Neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions. Acta Neuropathol. 1992;83:453–60.

Spillantini MG, Schmidt ML, Lee VM, Trojanowski JQ, Jakes RGM. α-Synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature. 1997;388:839–40.

Ozawa T, Paviour D, Quinn NP, Josephs KA, Sangha H, Kilford L, et al. The spectrum of pathological involvement of the striatonigral and olivopontocerebellar systems in multiple system atrophy: clinicopathological correlations. Brain. 2004;127:2657–71.

Brettschneider J, Suh E, Robinson JL, Fang L, Lee EB, Irwin DJ, et al. Converging patterns of α-Synuclein pathology in multiple system atrophy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2018;77:1005–16.

Gilman S, Low P, Quinn N, Albanese A, Ben-Shlomo Y, Fowler C, et al. Consensus statement on the diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. J Neurol Sci. 1999;163:94–8.

McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, Halliday G, Taylor J-P, Weintraub D, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurology. 2017;89:88–100.

Watanabe H, Saito Y, Terao S, Ando T, Kachi T, Mukai E, et al. Progression and prognosis in multiple system atrophy. Brain. 2002;125:1070–83.

Figueroa JJ, Singer W, Parsaik A, Benarroch EE, Ahlskog JE, Fealey RD, et al. Multiple system atrophy: prognostic indicators of survival. Mov Disord. 2014;29:1151–7.

Marttila RJ, Rinne UK. Progression and survival in Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 1991;136:24–8.

Papp MI, Lantos PL, Terry RD, Onorato M, Autilio-Gambetti L, Gambetti P, et al. Accumulation of tubular structures in oligodendroglial and neuronal cells as the basic alteration in multiple system atrophy. J Neurol Sci. 1992;107:172–82.

Nishie M, Mori F, Yoshimoto M, Takahashi H, Wakabayashi K. A quantitative investigation of neuronal cytoplasmic and intranuclear inclusions in the pontine and inferior olivary nuclei in multiple system atrophy. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2004;30:546–54.

Guo JL, Lee VMY. Cell-to-cell transmission of pathogenic proteins in neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Med. 2014;20:130–8.

Goedert M, Masuda-Suzukake M, Falcon B. Like prions: the propagation of aggregated tau and α-synuclein in neurodegeneration. Brain. 2017;140:266–78.

Prusiner SB, Woerman AL, Mordes DA, Watts JC, Rampersaud R, Berry DB, et al. Evidence for α-synuclein prions causing multiple system atrophy in humans with parkinsonism. Proc Natl Acad Sci. USA. 2015;112:E5308–17.

Watts JC, Giles K, Oehler A, Middleton L, Dexter DT, Gentleman SM, et al. Transmission of multiple system atrophy prions to transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:19555–60.

Peng C, Gathagan RJ, Covell DJ, Medellin C, Stieber A, Robinson JL, et al. Cellular milieu imparts distinct pathological α-synuclein strains in α-synucleinopathies. Nature. 2018;557:558–63.

Dhillon J-KS, Riffe C, Moore BD, Ran Y, Chakrabarty P, Golde TE, et al. A novel panel of α-synuclein antibodies reveal distinctive staining profiles in synucleinopathies. PLoS ONE 2017;12:e0184731.

Trojanowski JQ, Revesz T. Neuropathology Working Group on MSA. Proposed neuropathological criteria for the post mortem diagnosis of multiple system atrophy. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2007;33:615–20.

Rutherford NJ, Brooks M, Giasson BI. Novel antibodies to phosphorylated α-synuclein serine 129 and NFL serine 473 demonstrate the close molecular homology of these epitopes. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2016;4:80.

Giasson BI, Jakes R, Goedert M, Duda JE, Leight S, Trojanowski JQ, et al. A panel of epitope-specific antibodies detects protein domains distributed throughout human α-synuclein in lewy bodies of Parkinson’s disease. J Neurosci Res. 2000;59:528–33.

Waxman EA, Giasson BI. Specificity and regulation of casein kinase-mediated phosphorylation of alpha-synuclein. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2008;67:402–16.

Sacino AN, Brooks M, Thomas MA, McKinney AB, McGarvey NH, Rutherford NJ, et al. Amyloidogenic α-synuclein seeds do not invariably induce rapid, widespread pathology in mice. Acta Neuropathol. 2014;127:645–65.

Duda JE, Giasson BI, Gur TL, Montine TJ, Robertson D, Biaggioni I, et al. Immunohistochemical and biochemical studies demonstrate a distinct profile of alpha-synuclein permutations in multiple system atrophy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59:830–41.

Wenning GK, Seppi K, Tison F, Jellinger K. A novel grading scale for striatonigral degeneration (multiple system atrophy). J Neural Transm. 2002;109:307–20.

Jellinger KA, Seppi K, Wenning GK. Grading of neuropathology in multiple system atrophy: Proposal for a novel scale. Mov Disord. 2005;20(S12):S29–36.

Ozawa T, Tada M, Kakita A, Onodera O, Tada M, Ishihara T, et al. The phenotype spectrum of Japanese multiple system atrophy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2010;81:1253–5.

Yabe I, Soma H, Takei A, Fujiki N, Yanagihara T, Sasaki H. MSA-C is the predominant clinical phenotype of MSA in Japan: analysis of 142 patients with probable MSA. J Neurol Sci. 2006;249:115–21.

Kai H, Shin R-W, Ogino K, Hatsuta H, Murayama S, Kitamoto T. Enhanced antigen retrieval of amyloid β immunohistochemistry. J Histochem Cytochem. 2012;60:761–9.

Christensen DZ, Bayer TA, Wirths O. Formic acid is essential for immunohistochemical detection of aggregated intraneuronal Aβ peptides in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res. 2009;1301:116–25.

Beach TG, White CL, Hamilton RL, Duda JE, Iwatsubo T, Dickson DW, et al. Evaluation of α-synuclein immunohistochemical methods used by invited experts. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116:277–88.

Lu C-F, Soong B-W, Wu H-M, Teng S, Wang P-S, Wu Y-T. Disrupted cerebellar connectivity reduces whole-brain network efficiency in multiple system atrophy. Mov Disord. 2013;28:362–9.

Wang P-S, Yeh C-L, Lu C-F, Wu H-M, Soong B-W, Wu Y-T. The involvement of supratentorial white matter in multiple system atrophy: a diffusion tensor imaging tractography study. Acta Neurol Belg. 2017;117:213–20.

Cykowski MD, Coon EA, Powell SZ, Jenkins SM, Benarroch EE, Low PA, et al. Expanding the spectrum of neuronal pathology in multiple system atrophy. Brain. 2015;138(Pt 8):2293–309.

Acknowledgements

These studies were supported by grants P50 AG047266, R01NS089622, and R01NS100876. JSD was supported by grant T32NS082168. Tissue samples were supplied by the University of Florida Neuromedicine Human Brain Tissue Bank. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dhillon, JK.S., Trejo-Lopez, J.A., Riffe, C. et al. Dissecting α-synuclein inclusion pathology diversity in multiple system atrophy: implications for the prion-like transmission hypothesis. Lab Invest 99, 982–992 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41374-019-0198-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41374-019-0198-9

This article is cited by

-

Unique seeding profiles and prion-like propagation of synucleinopathies are highly dependent on the host in human α-synuclein transgenic mice

Acta Neuropathologica (2022)

-

Robust α-synuclein pathology in select brainstem neuronal populations is a potential instigator of multiple system atrophy

Acta Neuropathologica Communications (2021)

-

Disease-, region- and cell type specific diversity of α-synuclein carboxy terminal truncations in synucleinopathies

Acta Neuropathologica Communications (2021)

-

Multiple system atrophy-associated oligodendroglial protein p25α stimulates formation of novel α-synuclein strain with enhanced neurodegenerative potential

Acta Neuropathologica (2021)

-

Insights into the pathogenesis of multiple system atrophy: focus on glial cytoplasmic inclusions

Translational Neurodegeneration (2020)